Nicholas Biddle

The Baltimore Riots 1861

Nick Biddle and the First Defenders

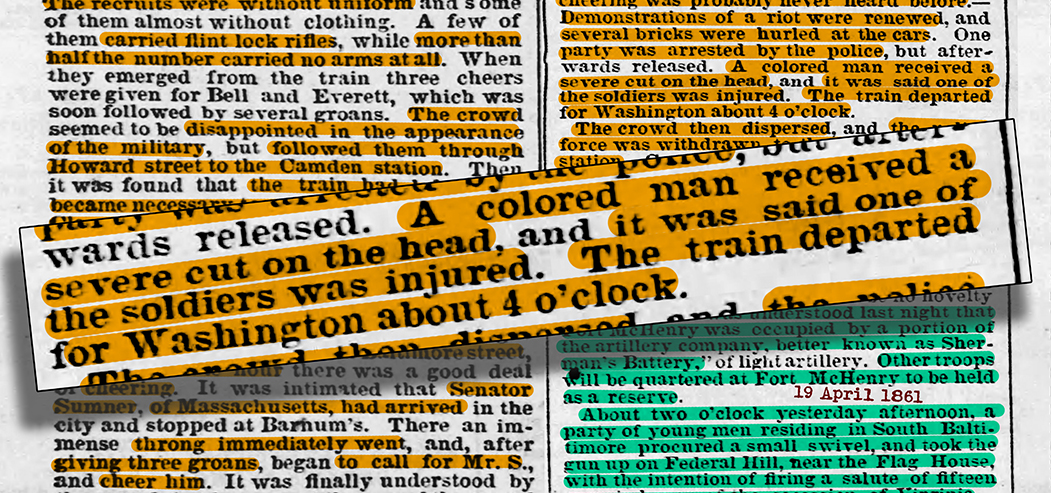

18 April 1861 after a day of screaming, hollering, yelling, cursing, throwing bricks, or portions of cobblestones that put men in the hospital, fighting for their lives. But, it wasn't enough, and it certainly wasn't the end of it, in fact, they were just warming up, for worse things to come the following day.

Click Here to View 18 April 1861 Newspaper Article

19 April 1861, Southern sympathizers attacked the Massachusetts 6th Regiment Infantry, screaming, hollering, yelling, cursing, throwing bricks, or pieces of cobblestone, and that was the least of their troubles. Not long after bricks were hurled in the direction of the soldiers, the report of a handgun was heard to have rung out in the area. Before long, shots were heard coming from both sides. Later the military denied having fired on the crowd, but these shootings were witnessed by Marshal Frey, Mayor Brown and many others. Four soldiers were killed in what has since become known as the Pratt Street Riots, or the Baltimore Riot of 1861 or the Pratt Street Massacre. [New York Public Library]

Click Here to View 19 April 1861 Newspaper Article

Click HERE to Hear Audio

The first man to shed blood during the Civil war was an escaped slave by the name of Nicholas Biddle from Pottsville, PA. Due to his having escaped a life of slavery very little is known of Mr. Biddle's life. From what we have learned he was born to slave parents in Delaware circa 1796. At some point, he escaped slavery and settled in Pennsylvania. It was common practice for escaped slaves to change their names to avoid capture, two stories told of Nicholas Biddle.

According to one historian's findings; Biddle escaped to Philadelphia and got a job as a servant for Nicholas Biddle, the wealthy financier, and president of the Second Bank of the United States. In this story, the former slave and the financier traveled to Pottsville for a dinner meeting of entrepreneurs and industrialists at nearby Mount Carbon to celebrate the first successful operation of an anthracite-fueled blast furnace in America. The servant remained in Pottsville to live. Another account is that Biddle relocated from Delaware directly to Pottsville and became a servant at the hotel where the aforementioned celebratory dinner was held, at which he met the famous Biddle.

In any event, we know that he adopted the name of the prominent Philadelphian, and by 1840 Nicholas Biddle was residing in Pottsville. He worked odd jobs to earn a living, including street vending, selling oysters in the winter and ice cream in the summer. The 1860 U.S. census lists his occupation as "porter."

Biddle befriended members of a local militia company, the Washington Artillerists, and attended their drills and excursions for the next 20 years. The company members were fond of Biddle and treated him as one of their own, and although African Americans were not permitted to serve in the militia, they gave him a uniform to wear.

At the outbreak of the Civil War and the fall of Fort Sumter on April 15, 1861, President Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteers to serve for three months to suppress the insurrection in the South. Unlike other antebellum militia units, the Washington Artillery had maintained a state of readiness and was among the first companies to respond to Lincoln's call to arms.

Two days later, the Washington Artillerists departed Pottsville by train to enter the war, along with 65-year-old Nicholas Biddle, who served as an aide to the company's commanding officer, Captain James Wren.

On April 18, five companies, numbering some 475 men, were sworn in at Harrisburg and mustered into the service of the United States. That is, all except for Nicholas Biddle, who as an African American was prohibited from serving in the U.S. Army.

The soldiers left on an emergency order to defend Washington, DC against a rumored Confederate attack. But in 1861, there was no continuous passenger rail service through Baltimore, and when the soldiers detained in the largest city in the slave state of Maryland, they encountered a hostile mob of pro-Southern sympathizers.

As the companies marched to meet their trains, members of the mob taunted the soldiers and hurled bricks and stones. Biddle, a black man in uniform, was an easy target. Someone threw a brick, striking Biddle in his head and knocking him to the ground. This made Nicholas Biddle the first casualty caused by hostile action in the Civil War.

The wound was grave enough that it exposed his bone. It was reportedly the first and most serious injury suffered that day, and he bore the scar the rest of his life.

An anxious President Lincoln learned of the arrival of the five Pennsylvania companies and of their treacherous passage through the mob at Baltimore. The morning after they arrived in Washington, Lincoln personally thanked each member of the five companies and singled out the wounded for special recognition.

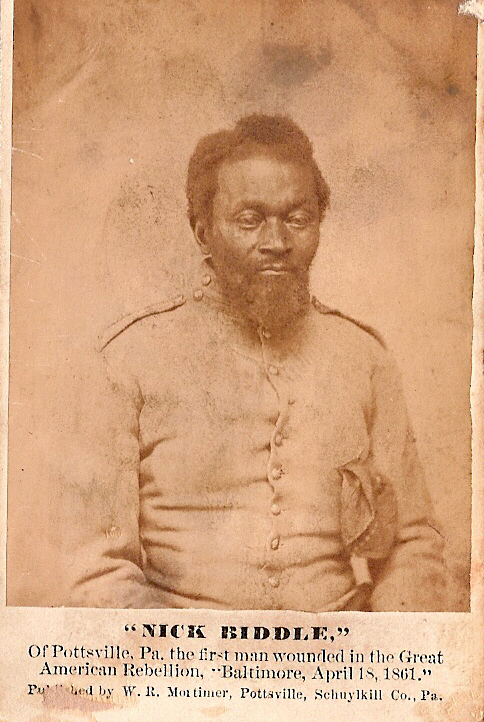

After his military service, Biddle returned to relative obscurity in Pottsville, where he eked out a living performing odd jobs. In the summer of 1864, he appeared at the Great Central Fair in Philadelphia, where photographs of him in a Washington Artillerists uniform, captioned "the first man wounded in the Great American Rebellion," were sold to raise funds for the relief of Union soldiers. In the end, however, Biddle was forced to solicit alms to make ends meet. He died destitute in 1876 without even enough money to cover his burial expenses. Surviving members of the Washington Artillerists and the National Light Infantry each donated a dollar to purchase a simple headstone for him, and they had it inscribed: "In Memory of Nicholas Biddle, Died Aug.2, 1876, Aged 80 years. His was the Proud Distinction of Shedding the First Blood in the Late War for the Union, Being Wounded while marching through Baltimore with the First Volunteers from Schuylkill County, 18 April 1861. Erected by his Friends in Pottsville."

Throughout the remainder of his life, Biddle retained unpleasant memories of his perilous journey with the Washington Artillerists through Baltimore. Although it garnered him the "proud distinction of shedding the first blood," he was often heard to remark "that he would go through the infernal regions with the artillery, but would never again go through Baltimore."

![]()

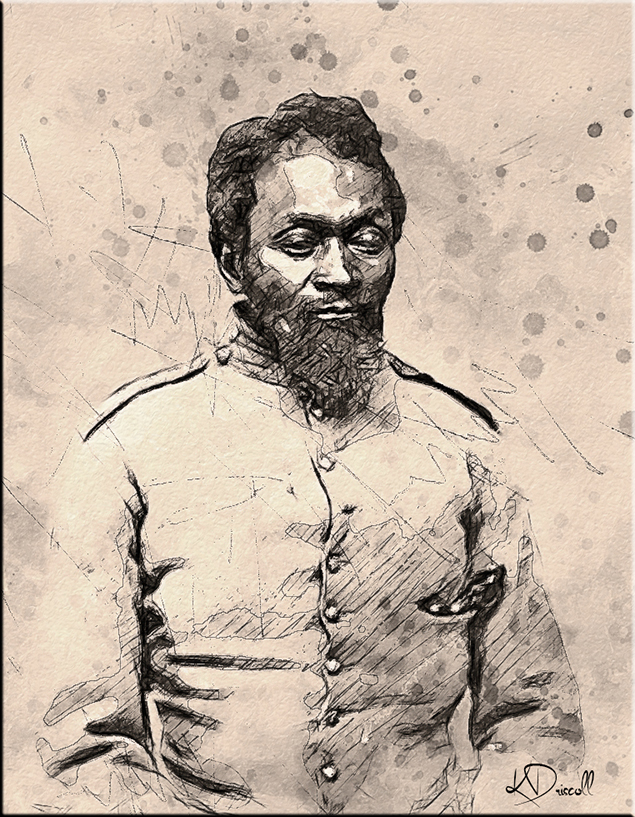

This card/photo served as a remarkable testament to the bravery and sacrifice of Nick Biddle, who was recognized as the first man wounded during the significant event that came to be known as the Great American Rebellion. By proudly wearing his uniform and attending various fairs and events, Biddle aimed to commemorate his role in history and inspire others with his story. The fact that this card/photo was printed by W.R. Mortimer of Pottsville, Schuylkill Co., Pa., adds an intriguing detail about the local history.![]()

Click the above article, or HERE to see full article

Click the above article, or HERE to see full article

The violence erupted when a mob of southern sympathizers attacked a group of Union soldiers passing through the city on their way to Washington, DC. The tragic events that took place on Howard Street on the 18th and Pratt Street on the 19th, leading to death and serious injury, marked a turning point in the nation's history, highlighting the deep divisions in our country, and serving as a grim precursor to the widespread violence and bloodshed that would soon engulf the entire country into a Civil War.

![]()

Nicholas Biddle and the First Defenders

By Ronald S. Coddington

18 April, 2011

On the afternoon of April 18, 1861, Nick Biddle was quietly helping his unit, the Washington Artillery from Pottsville, Pa., set up camp inside the north wing of the Capitol building. The day before, he was almost killed.

Biddle was a black servant to Capt. James Wren, who oversaw the company of about 100 men. On April 18 the Washington Artillery had been one of several Army outfits, totaling about 475 men, heading through Baltimore en route to Washington, D.C., in response to President Lincoln’s call for 75,000 troops to put down the Southern rebellion.

Captain Wren, Biddle and the others were aware of Baltimore’s pro-secession sentiment and expected trouble. One volunteer reportedly asked Biddle if he was afraid to face rowdy “plug-uglies” and jokingly warned, “They may catch you and sell you down in Georgia.” Biddle replied in dead earnest that he was going to Washington trusting in the Lord and that he wouldn’t be scared away by the devil himself — or a bunch of thugs.

The Pennsylvanians formed a line and prepared to march through Baltimore to another station, where they could catch a Washington-bound train. The regulars would lead the way. The line started and moved rapidly, shielded from the abusive mobs by policemen stretched 10 paces apart. A private recalled the “Roughs and toughs, ‘longshoremen, gamblers, floaters, idlers, red-hot secessionists, as well as men ordinarily sober and steady, crowded upon, pushed and hustled the little band and made every effort to break the thin line.”

The mob derided the volunteers and cheered for Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy. Some aimed their abuse at Biddle. Capt. Wren remembered, “The crowd raised the cry, ‘Nigger in uniform!’ and poor old Nick had to take it.”

Around the halfway point of the journey, the regular troops split off and marched to Fort McHenry, leaving the Pennsylvanians alone. “At this juncture the mob was excited to a perfect frenzy, breaking the line of the police and pushing through the files of men, in an attempt to break the column,” wrote one historian. The boldest in the crowd spit, kicked, punched and grabbed at the coattails of the volunteers.

As the Pennsylvanians neared the station, rioters chucked cobblestones and jagged pieces of broken brick. The bombardment intensified as the volunteers arrived at the station and began to board the cars. Suddenly a chunk of brick struck Biddle in the head and left a deep, profusely bleeding cut. He managed to get on the train as the mob climbed on top of the cars and jumped up and down on the roofs. Biddle found a comfortable spot, wrapped his head in a handkerchief, and then pulled his fatigue cap close over the wound.

When the Pennsylvanians finally arrived in Washington that evening, they received a very different reception, as enthusiastic crowds welcomed them as saviors. They occupied temporary barracks in the north wing of the Capitol. One officer remembered that, when Biddle entered the rotunda of the building, “He looked up and around as if he felt that he had reached a place of safety, and then took his cap and the bloody handkerchief from his head and carried them in his hand. The blood dropped as he passed through the rotunda on the stone pavement.”

A grateful President Lincoln later greeted the Pennsylvanians. He reportedly shook hands with Biddle and encouraged him to seek medical attention. But Biddle refused. He preferred to remain with the company. At the time some considered Biddle’s blood the first shed in hostility during the Civil War.

The House of Representatives later passed a resolution thanking the Pennsylvanians for their role in defense of the capital. The volunteers came to be known as the “First Defenders” in honor of their early response to Lincoln’s call to arms.

Sources: The Baltimore Sun, April 19, 1861; James M. Guthrie, “Camp-Fires of the Afro-American”; Samuel P. Bates, “History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5,” Vol. 1; Heber S. Thompson, “The First Defenders”; Weekly Press (Philadelphia, Pa.), March 24 and July 21, 1886; John D. Hoptak, “A Forgotten Hero of the Civil War,” Pennsylvania Heritage, Spring 2010; W.W. Munsell & Co., “History of Schuylkill County, Pa.”; Lowell (Massachusetts) Daily Citizen and News, April 20, 1870; U.S. House of Representatives, Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States; Weekly Miners’ Journal (Pottsville, Pa.), Aug. 11, 1876; Herrwood E. Hobbs, “Nicholas Biddle,” Historical Society of Schuykill County, 1961.

Ronald S. Coddington is the author of “Faces of the Civil War” and “Faces of the Confederacy.” His forthcoming book profiles the lives of men of color who participated in the Civil War. He writes “Faces of War,” a column in the Civil War News.

Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll