Abraham Lincoln Crushes Civil Liberties in Maryland

Abraham Lincoln is widely regarded as one of the nation’s greatest Presidents.[1] He is the subject of at least 15,000 books.[2] A popular poem (later set to music) responded to Lincoln’s call for troops in biblical terms: “We are coming, Father Abraham, three hundred thousand more.…”[3] Upon Lincoln’s death, Bishop Horatio Potter wrote that “[a] glorious career of service and devotion is crowned with a martyr’s death.”[4] Lithographs in the aftermath of the assassination depicted the apotheosis of Lincoln. In short, Lincoln has been venerated among both scholars and the public.

Despite the mostly reverent treatment, little has been written about Lincoln’s treatment of civil liberties during the Civil War.[5] Even then, the few full-length scholarly works have generally excused Lincoln’s conduct or otherwise justified his actions as necessary to conduct the war. One historian admitted “[t]he skimpiness of the serious literature suggests that historians have been more or less embarrassed by Lincoln’s record on the Constitution.”[6] As a result, there is a gap in the scholarly work regarding President Lincoln’s role regarding civil liberties.

This paper seeks to fill that gap by examining Lincoln’s conduct as he tried to keep Maryland in the Union in 1861. Ultimately, Abraham Lincoln succeeded through a deliberate campaign to suppress civil liberties, including the illegal suspension of habeas corpus, arbitrary arrests of elected officials, interference in Maryland’s elections, and the shuttering of newspapers sympathetic to the Confederacy. Whether Maryland would have seceded may never well be known, but Lincoln’s calculated conduct ensured that it would not happen.

Maryland’s complex role in the Civil War grew out of several factors that developed during the sectional crisis of the 1850s. A border state that was home to nearly 90,000 slaves, Maryland became increasingly connected to the industrial North when the Northern Central Railway was completed in 1858 between Baltimore, Maryland, and Sunbury, Pennsylvania.[7] But most important was its geography, surrounding Washington, D.C. on three sides.[8] Writing about his father John Adams Dix’s responsibilities as commander of the Department of Maryland in 1861, Morgan Dix wrote that “the loss of Maryland would have been the loss of the national capital, and perhaps, if not probably, the loss of the Union cause.”[9]

The 1860 presidential election was another measure of the complexity of Maryland’s situation. Maryland voted narrowly for the Southern Democratic candidate John C. Breckinridge over the Constitutional Union candidate John Bell by 45.93% to 45.14%. Stephen Douglas captured 6.45%, while Lincoln netted just 2.48%, or less than 2,300 votes statewide.[10] In the weeks after the election, the Baltimore Sun was convinced that if South Carolina and other states of the deep South seceded, Maryland would soon follow: “If disunion proves inevitable, the line will be drawn North of Maryland.”[11] Based on the 1860 voting patterns, historian Lawrence M. Denton concluded that “Maryland, if free to choose their own course, would have…stay[ed] with their section and join[ed] the states of the upper South in the Southern Confederacy.”[12]

Baltimore was particularly hostile to Lincoln, and home to an alleged plot to assassinate the President-elect as he passed through on his way to Washington.[13] When private detective Allan Pinkerton convinced Lincoln to pass through Baltimore under cover of darkness, the Sun blasted Lincoln, declaring that “[w]e do not believe the Presidency can ever be more degraded by any of his successors than it has been by him….” the night before the publicly-scheduled train.[14] Whether or not the threats against Lincoln were fully-formed, the potential for violence in Baltimore was genuine.

The critical tipping points that moved the nation from sectional conflict to war came in April 1861. For strategic reasons related to geography, Maryland’s fate was closely tied with that of Virginia. On April 4, 1861, Virginia voted against secession.[15] But two days later, Lincoln informed Governor Pickens of South Carolina that Fort Sumter would be re-provisioned with force, if necessary.[16] Then, on April 12, Confederate troops fired on Fort Sumter, and Major Robert Anderson surrendered the Fort the next morning.[17]

On April 15, President Lincoln pressed forward and called for 75,000 volunteers.[18] Two days later, the Virginia Secessionist Convention voted in favor of a referendum of secession, which was subsequently ratified by its citizens on May 23, 1861.[19] The reaction to Lincoln’s call for troops was exceptionally violent in Maryland, where Southern sympathizers attacked the 6th Massachusetts Regiment as they passed through the city.[20] Maryland Governor Thomas Hicks, together with Baltimore Mayor George Brown and Marshall of Police of Baltimore George P. Kane, decided to destroy the railroad bridges around Baltimore to prevent Union troops from passing through the city.[21] Then, on April 22, Governor Hicks, who had previously resisted such efforts, called for a special session of the Maryland legislature to consider secession.[22] Lincoln considered arresting the members of the legislature but decided to “watch and await their actions.”[23] If Maryland chose to arm its citizens against the United States, General Benjamin Butler was authorized to “adopt the most prompt and efficient means to counteract, even if necessary to the bombardment of their cities, and in the extremest necessity suspension of the writ of habeas corpus.”[24] A delegation of the Maryland legislature that met with Lincoln reported that they were “painfully confident that a war is to be waged to reduce all the seceding States to allegiance to the United States Government, and that the whole military power of the Federal Government will be exerted to accomplish that purpose.”[25] On April 27, Lincoln authorized suspension of the writ between Philadelphia and Washington, D.C.[26] This single event would set the stage for the most widespread violations of civil liberties throughout the war. The suspension of the writ, the military occupation of Maryland, and the ever-present threat of military force became the primary tools for keeping Maryland in the Union.

The sole legal challenge to Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus in Maryland came in the case of John Merryman, a Maryland militia leader who had participated in the destruction of the bridges and rail lines around Baltimore at the behest of Governor Hicks. Merryman was arrested on May 25, 1861, and imprisoned at Fort McHenry. Merryman filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus with Chief Justice Roger Taney, who cited historical precedent and the placement of the Suspension Clause in Article I to rule that “the privilege of the writ could not be suspended except by act of Congress.”[27] The administration promptly ignored the decision and refused to honor the writ. The inability of the judiciary to enforce its decision meant that Lincoln’s suspension of the writ would go unchallenged and arbitrary arrests would continue.

The President sought to justify his decision to suspend the writ in a special message to Congress on July 4.[28] Lincoln argued that the Constitution was silent as to whether the President or Congress possessed the power to suspend the writ; and since Congress was not in session, the President could make such a decision lawfully. Moreover, even if the power belonged to Congress, he argued that his responsibility to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed” justified his actions: “are all the laws but one go unexecuted, and the government itself go to pieces lest that one be violated?”[29] Whether or not Lincoln intended Congress to ratify his actions, Congress did not enact any such legislation until 1863.[30]

Even while Lincoln was preparing his message to Congress, his suspension of the writ in Maryland was having an immediate impact. Union troops flooded into Maryland and seized control of Annapolis and Baltimore.[31] Arrested and imprisoned at Fort McHenry were Baltimore Mayor George P. Brown, the entire city council, Marshal of Police George P. Kane, and all the police commissioners as well as U.S. Congressman Henry May.[32] In September, military officials arrested at least 30 members of the legislature who were deemed to be sympathetic to the South.[33] Captured War Department correspondence indicated that the administration believed large majorities of both the House of Delegates and State Senate were likely to vote for secession, and carried out a deliberate effort to deny their ability to assemble.[34] In April, Lincoln had decided against arresting members of the Maryland legislature, acknowledging their right to assemble and debate, but now the administration now determined that no vote would be allowed.[35] The arrest and imprisonment of members of the state legislature not only denied them the opportunity to assemble but was designed to interfere with the fall elections. General Nathaniel P. Banks, who commanded military districts in both eastern and western Maryland during 1861, explained the administration’s strategy: “The secession leaders–enemies of the people–were replaced and loyal men assigned to….their duties. This made Maryland a loyal State….”[36] Many of these elected officials would remain imprisoned until November 1862.[37] Here the combination of arbitrary arrest, military occupation, and the threat of force represented a particularly acute chilling effect on civil liberties.

The extent to which the Lincoln administration went to suppress press freedoms in Maryland was exemplified by the case of Frank Key Howard. The grandson of Francis Scott Key, Howard was the editor of the Baltimore Daily Exchange, a newspaper sympathetic to the South. Arrested as “a measure of military precaution,” Howard was imprisoned and spent 14 months in Fort McHenry, Fort Lafayette, and Fort Warren.[38] When Howard’s account of a political prisoner was published in 1863, the publishers of his book were arrested.[39] Historian Sidney T. Matthews estimated that at least nine Baltimore newspapers, including Howard’s Daily Exchange, were suppressed during the war, including the arrest and imprisonment of their editors or owners.[40] Matthews concluded that “the arbitrary arrest of disloyal editors the action taken by the Government, for the first year and a half of the War, had no basis in law.”[41] The suppression of newspapers like the Daily Exchange as “military precautions” represented a particularly odious violation of freedom of the press known as prior restraint.

A review of the notable full-length scholarly treatments of Lincoln’s role in civil liberties during the war reveals a trend of generally excusing Lincoln’s conduct or otherwise justifying his actions as necessary to conduct the war. James G. Randall’s Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln, first published in 1926, reflected what one historian called Randall’s “curious ambivalence” toward Lincoln’s conduct.[42] Randall was at times highly critical of the Union’s suppressive policies but tempered their treatment by his experience in the Wilson administration during World War I. Randall himself wrote about his manuscript that “I may have gone too far in justifying the extreme war powers. My real convictions are…that many dangers lurk in the war power theory. Possibly my admiration for Lincoln has carried me too far.”[43]

Dean Sprague’s Freedom Under Lincoln, published in 1965, was also critical of Lincoln’s abuses of civil liberties. Sprague was particularly harsh on the administration’s policies in Maryland. But the author found Lincoln “scarcely touched by [the administration’s policy of suppression] personally,” “no intimate understanding of the workings of the executive branch, or of Washington politics,” and “reluctant to interfere in the day-to-day administration of the affairs of his cabinet officers.”[44] Instead, the villain was Secretary of State William E. Seward, who Sprague asserted had engineered the administration’s policy of repression. Sprague even called Lincoln a “humanitarian,” and charitably suggested that the President “would probably have sought…to prevent his successors from following this dangerous precedent.”[45] Sprague acknowledged that Lincoln was keenly aware of the suppression, and provided few examples of the President’s supposedly leniency.[46] But even if Seward was mostly responsible for carrying out the Union’s policies of suppression in 1861, one must wonder why Sprague did not hold the President at least equally accountable, precisely because Lincoln alone suspended the writ of habeas corpus that allowed Seward’s suppression program to flourish. If Lincoln ever believed that Seward’s efforts went beyond the President’s limits, it is curious that the President so rarely intervened.

The most recent scholarly work on Lincoln’s treatment of civil liberties is Mark E. Neely, Jr.’s The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties. Neely examined the military records of civilians who had been arrested and imprisoned during the war after the President suspended habeas corpus. He concluded that more than 14,000 civilians were subject to arbitrary arrest, “but they were of less significance in the history of civil liberties than anyone ever imagined” because a majority of the arrests were “refugees, informers, guides, Confederate defectors, carriers of contraband goods, and other such persons as came between or in the wake of large armies. They may have been civilians, but their political views were irrelevant.”[47] Neely’s conclusion may very well be correct for many of the thousands of civilians arrested and imprisoned, but ultimately minimizes the brutal suppression of civil liberties in Maryland where legislators were imprisoned simply based upon how they might vote; where Union policies sought to interfere with the state’s elections; and where editors were imprisoned and newspapers suppressed for what they might publish.

Other notable works about Lincoln are worth mentioning here. In James M. McPherson’s Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief, the eminent Civil War historian presented a confusing and unsatisfying review of Lincoln’s role on civil liberties. For example, McPherson wrote “some of the Lincoln administration’s actions, such as the arrest of Maryland legislators and other officials in September 1861, seemed excessive and unjustified by any reasonable military necessity.”[48] He also recognized that Lincoln’s controversial actions provided precedents for later wartime presidents.[49] Yet McPherson then pivoted to proclaim that “the infringement of civil liberties from 1861 to 1865 seems mild indeed” as compared to later wars.[50] In this way McPherson fell into the same circular reasoning trap as James G. Randall, recognizing the dangerous precedents Lincoln established but then minimizing them compared to what they believed were greater threats in later wars that built upon those very precedents. In Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution, McPherson found support for Lincoln’s violation of civil liberties in both Lincoln’s July 1861 message to Congress and in the Emancipation Proclamation.[51] According to Lincoln, the survival of the nation was at stake.[52] Finally, McPherson concluded that Lincoln shifted America from a nation based upon negative liberty to one based primarily on positive liberty, which the author regarded as an optimistic change.[53]

McPherson’s belief that Lincoln’s conduct of the war changed the nature of the nation raises some final points that remains both unanswered and highly relevant still today. It is worth considering if the preservation of the union and a second American revolution in favor of positive liberty was worth the cost. More fundamentally, it is worth asking what is it that was preserved in a nation so deeply changed by the conflict. Historian Richard Gamble suggested that Lincoln “deployed a power civil religion, civil history, and civil philosophy to superimpose one reading of American history onto any competitors.”[54] Thus, the nation has become a propositional nation rather than a nomocratic one.[55] Ultimately, Lincoln’s consequentialist approach to civil liberties ushered in a more powerful executive branch that Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. called The Imperial Presidency.[56] Presidential historian Clinton Rossiter called executive war powers a “constitutional dictatorship,” and believed that Lincoln’s “noble actions” and “tremendous” reputation largely justified his precedent.[57] Rossiter recognized that ‘[t]he only check upon [a less democratic and less patriotic] man would be the normal constitutional and popular limitations of the American system.”[58] One must wonder whether Rossiter recognized the irony of relying upon “normal constitutional and popular limitations” to check what virtually every historian has recognized as extra-constitutional powers.

Maryland, a border state home to nearly 90,000 slaves, presented a complex challenge to the Lincoln administration because of its southern sympathies, its economic connections to the North, and its strategic geography. Lincoln quickly decided that the loss of Maryland would inevitably lead to the loss of the national capital and, most probably, the war itself. As a result, the President kept Maryland in the Union through a deliberate campaign to stifle civil liberties that included the suspension of habeas corpus, the arbitrary arrest and imprisonment of elected officials, the manipulation of Maryland’s elections, and the suppression of newspapers sympathetic to the Confederacy. Historians will continue to debate whether Maryland would have seceded without the suppression of civil liberties, but Lincoln’s calculated strategy ensured that it would not happen.

[1] C-SPAN, “Presidential Historians Survey 2017,” accessed April 17, 2019, https://www.c-span.org/presidentsurvey2017/.

[2] “Forget Lincoln Logs: A Tower of Books to Honor Abe,” NPR, February 20, 2012, https://www.npr.org/2012/02/20/147062501/forget-lincoln-logs-a-tower-of-books-to-honor-abe.

[3] O.H. Oldroyd, The Good Old Songs We Used to Sing, ’61 to ’65 (Washington, DC: 1902), 17.

[4] A Tribute of Respect by the Citizens of Troy, to the Memory of Abraham Lincoln (Troy, NY: Young & Benson, 1865), 29; Our Martyr President: Voices from the Pulpit of New York and Brooklyn (New York: Tibbals & Whiting, 1865).

[5] One exception is Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144 (C.C.D. Md. 1861), to be discussed later in this paper.

[6] Mark E. Neely, Jr., The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 232.

[7] Robert L. Gunnarsson, The Story of the Northern Central Railway (Sykesville, MD: Greenberg, 1991).

[8] James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (New York: Ballantine Books, 1988), 284-285.

[9] Morgan Dix, ed., Memoirs of John Adams Dix, vol. 2 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1883), 24.

[10] John Woolley and Gerhard Peters, The American Presidency Project, UC Santa Barbara, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/statistics/elections/1860.

[11] “The Preservation of the Union,” Baltimore Sun, November 27, 1860, 2.

[12] Lawrence M. Denton, A Southern Star for Maryland: Maryland and the Secession Crisis, 1860-1861 (Baltimore: Publishing Concepts, 1995), 27-39.

[13] Michael J. Kline, The Baltimore Plot: The First Conspiracy to Assassinate Abraham Lincoln (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2008).

[14] Ibid., 201-216; “The Great Lincoln Escapade,” Baltimore Sun, February 25, 1861, 2.

[15] McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 255.

[16] Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. IV (New Brunswick: Rutgers Univ. Press, 1953), 323-324.

[17] McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 273-274.

[18] Ibid., 274.

[19] Ibid., 279-280.

[20] Ibid., 285.

[21] George L. P. Radcliffe, Governor Thomas H. Hicks of Maryland And The Civil War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1901), 56-57.

[22] Ibid., 62-70.

[23] Abraham Lincoln, “April 25, 1861, Order to General Scott,” in John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Complete Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. 6 (Harrogate, TN: Lincoln Memorial University, 1894), 255-256.

[24] Ibid.

[25] John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, vol. 4 (New York: The Century Company, 1904), 172.

[26] Abraham Lincoln, “April 27, 1861, Order to General Scott,” in Nicolay and Hay, Complete Works, vol. 6, 258.

[27] U.S. Const., art I, § 9, cl. 2: ” The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it;” Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144 (C.C.D. Md. 1861) (No. 9487).

[28] Abraham Lincoln, “Message to Congress in Special Session, July 4, 1861,” in Nicolay and Hay, Complete Works, vol. 6, 297-325.

[29] Ibid., 309-310.

[30] George C. Sellery, Lincoln’s Suspension of Habeas Corpus as Viewed by Congress (Madison, WI: 1907), 246-263, 278-283.

[31] “Benj. F. Butler to Thos. H. Hicks,” in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies [hereinafter OR], Series I, vol. II (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880), 589-590; “General Butler’s proclamation,” in OR I:II, 30-31.

[32] “Order from General Scott for the arrest of the Commissioners,” OR I:II, 138-139; “Nath. P. Banks to the People of the City of Baltimore,” in OR II:I, 624-625 (Kane); “Allan Pinkerton to William H. Seward,” in OR II:I, 688 (Brown, May).

[33] “Arrest and Detention of Certain Members of the Maryland Legislature,” in OR II:I, 667-675.

[34] Secret Correspondence Illustrating the Condition of Affairs in Maryland (Baltimore, 1863), 14-30.

Denton, Southern Star, 152-153.

[35] Abraham Lincoln, “April 25, 1861, Order to General Scott,” in Nicolay and Hay, Complete Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. 6, 255-256.

[36] Fred Harvey Harrington, Fighting Politician: Major General N.P. Banks (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1948), 60.

[37] “Arrest and Detention of Certain Members of the Maryland Legislature,” in OR II:I, 667-675.

[38] “Case of Howard and Glenn of the Baltimore Exchange Newspaper,” in OR II:II, 778-779; Frank Key Howard, Fourteen Months in American Bastiles sic.

[39] Sidney T. Matthews, “Control of the Baltimore Press During the Civil War,” Maryland Historical Magazine 36, no. 2 (June 1941): 162.

[40] Ibid., 150.

[41] Ibid., 169.

[42] James G. Randall, Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln (Revised Edition) (Urbana, IL: The University of Illinois Press, 1951); Neely, Fate of Liberty, 228.

[43] Edwin P. Tanner to James G. Randall to Edwin P. Tanner, Sept. 20, 1924, in Neely, Fate of Liberty, 229.

[44] Dean Sprague, Freedom under Lincoln: Federal Power and Personal Liberty Under the Strain of Civil War (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965), 157-159.

[45] Ibid., 299-303.

[46] Ibid., 301.

[47] Neely, Fate of Liberty, 233-234.

[48] James M. McPherson, Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief (New York: The Penguin Press, 2008), 269-270.

[49] Ibid., 269.

[50] Ibid., 270.

[51] James M. McPherson, Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 57-64.

[52] Ibid., 59.

[53] Ibid., 61-64.

[54] Richard Gamble, “Gettysburg Gospel,” The American Conservative, November 14, 2013, https://www.theamericanconservative.com.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. The Imperial Presidency (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973).

[57] Clinton Rossiter, Constitutional Dictatorship: Crisis Government in the Modern Democracies (New York: Routledge, 2002), 223-239.

[58] Ibid., 239.

![]() Important Notice

Important Notice

The current page is not for public view; it is a workspace for the site’s owners and developers for research purposes. Visitors are requested to follow the provided link to access the actual article, which was written by Abraham Lincoln Crushes Civil Liberties in Maryland – Abbeville Institute

![]()

POLICE INFORMATION

We are always looking for copies of your Baltimore Police class photos, pictures of our officers, vehicles, and newspaper articles relating to our department and/or officers; old departmental newsletters, old departmental newsletters, lookouts, wanted posters, and/or brochures; information on deceased officers; and anything that may help preserve the history and proud traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to honor the fine men and women who have served with honor and distinction at the Baltimore Police Department. Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History: Ret Det. Kenny Driscoll

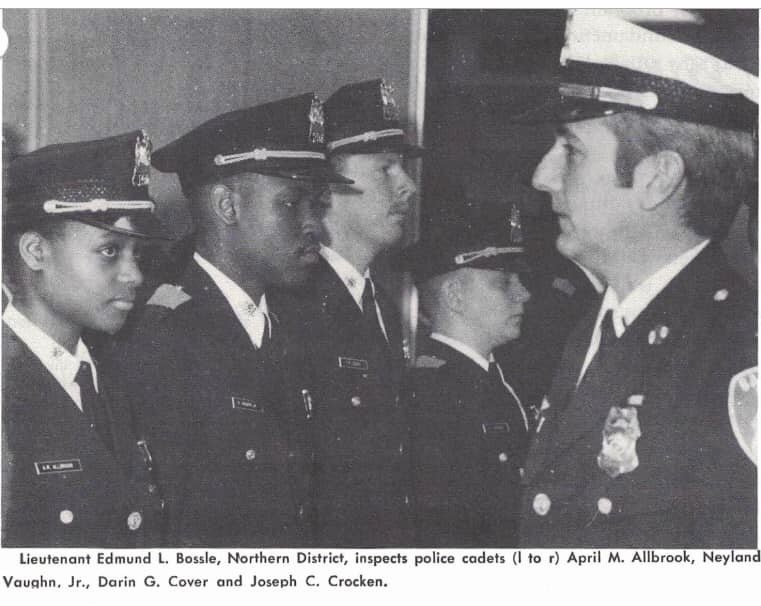

Lieutenant Edmund Bossle

Retired Lieutenant Edmund Bossle is a respected figure in the Baltimore Police Department. His career began on, 17 June, 1965, when he joined the department as a cadet. In fact, on the same day in 1965, Baltimore began its cadet program with Edmund Bossle as their first cadet. He is recognized for his service and contributions to the department and is listed in the Baltimore Police Department’s Hall of Fame.

Over the years, he rose through the ranks, reaching the position of lieutenant before his retirement. After 25 years of dedicated service, he retired from the Baltimore Police Department.

Following his retirement, he became the Assistant Director of Campus Police at Loyola College (now University), under Steve Tabeling, who was also a Baltimore Police legend. After his tenure at Loyola, Lt. Bossle served as a security manager at BWI for a year before going to work for Carefirst Blue Cross for a few years.

In the aftermath of the events of 9/11, Lt. Bossle joined the newly formed TSA in 2002 as a traveling instructor, opening federal checkpoints at several airports. He then took a permanent duty station at Orlando International Airport, from which he retired in January of 2015.

![]()

POLICE INFORMATION

We are always looking for copies of your Baltimore Police class photos, pictures of our officers, vehicles, and newspaper articles relating to our department and/or officers; old departmental newsletters, old departmental newsletters, lookouts, wanted posters, and/or brochures; information on deceased officers; and anything that may help preserve the history and proud traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to honor the fine men and women who have served with honor and distinction at the Baltimore Police Department. Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History: Ret Det. Kenny Driscoll

Detective John Calpin

Detective John Calpin, a distinguished member of the Baltimore Police Department, served with unwavering dedication in the Central District’s Patrol and Drug Enforcement Unit (DEU). His steadfast commitment to upholding law and order was highly esteemed within the community. From the start of his 30-year career in 1986 until his retirement in 2016, Detective Calpin consistently received praise from both his coworkers and the community he so tirelessly served. His significant contributions to the department and to the city of Baltimore have left a lasting legacy that continues to be greatly valued to this day.

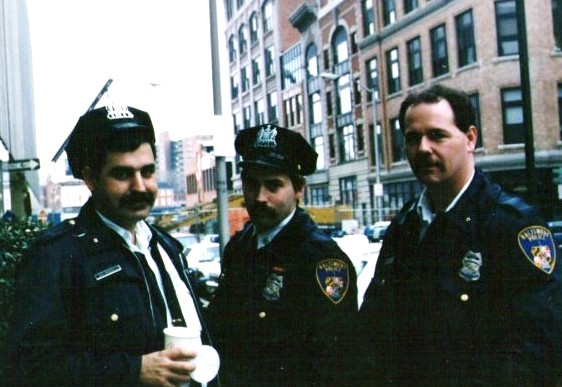

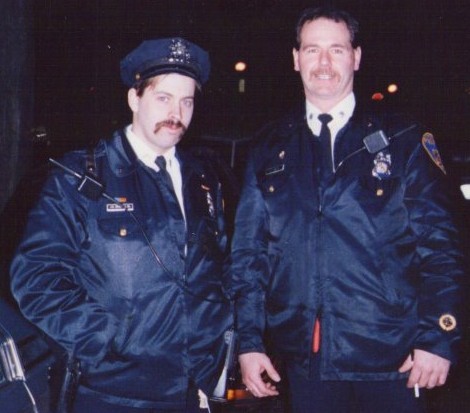

John Calpin, and Ken

Here, John was a patrolman badge number 606

with his partner, Ken Driscoll, badge number 3232

"Together, they made a mean pair of two."

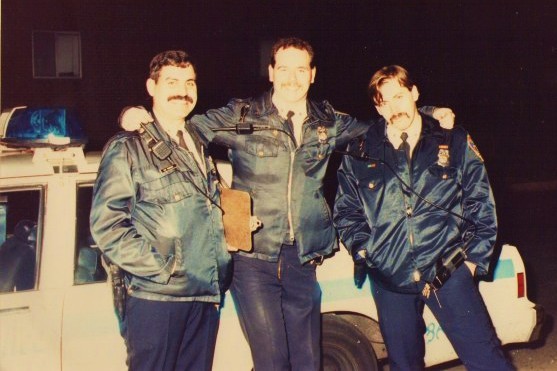

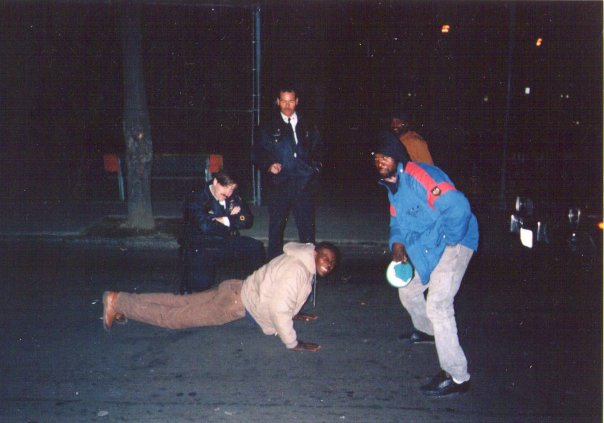

Here they are again: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

According to George Trainor, George was The Good, John was The Bad, and Kenny Driscoll was The Ugly

All three were fine with their titles, as they made a great team of police that did the job and did the job well.

John Calpin - Kenny Driscoll

John Calpin - Kenny Driscoll

Shortly After a Departmental Shooting 600 E. North Ave.

This has George Trainer, John Calpin and Kenny

George called them The Good The Bad and The Ugly

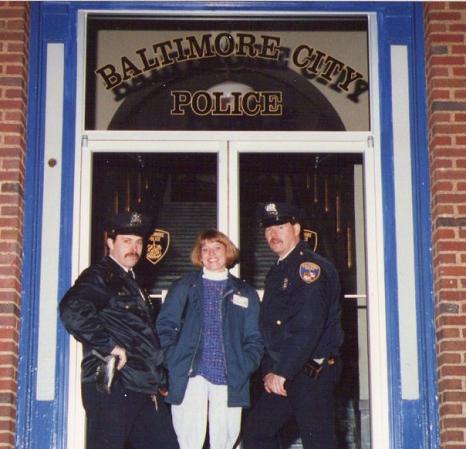

Kenny, Karin Sullivan Lipski, and John Calpin

These three never worked together, but Ken was partnered up with both of them.

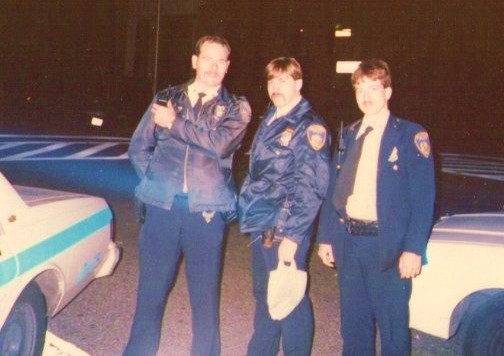

Left to Right, this is John Calpin, Ed Chaney and Ken

This is Kenny looking under the car to make sure no-one or nothing is under the car before it is towed.

Ken was told it looked like he was falling out of the car, So they took the picture for the joke. BTW It is

John Calpin is toward the front of the car; he is acting as if he is directing Ken into the parking place.

John Calpin, Ken and Officer Scott Bradshaw

This picture was taken the day Ken and John seized a safe containing 2 keys of cocaine. They tripped over it while chasing a suspect who bailed out of a stolen car and ran into an apartment. Since he was running from the police, when they knocked on the door, a lady answered, telling the officers she was alone and no one should be in the apartment with her. They went in and found him hiding in a closet in a near-empty room. The lady obviously living there said she wanted the suspect removed, and she told them to take the safe out too. Long story short, her boyfriend rented the apartment but only furnished one room for her. The other rooms were for his stash house. So, the suspect that was running in and out ended up getting a ten-year sentence for the drugs.

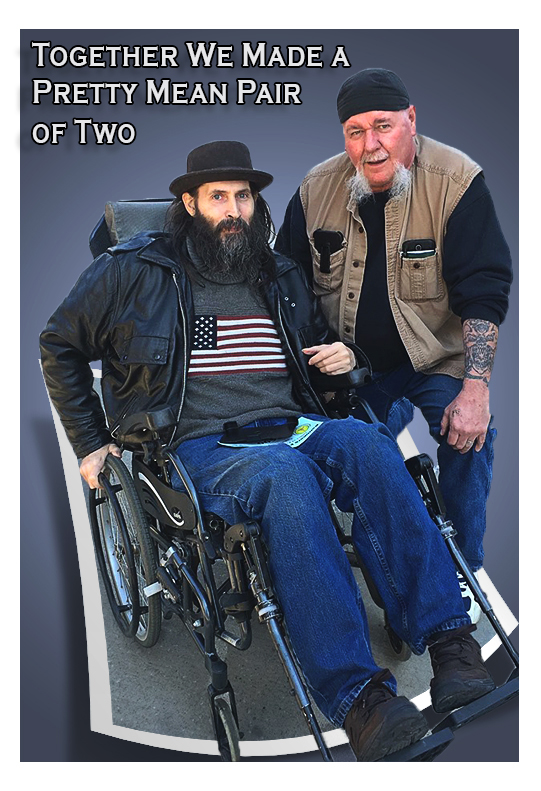

Ken Driscoll is in the wheelchair, with John kneeling beside him.

Ken Driscoll is in the wheelchair, with John kneeling beside him.

These two were partners on a midnight shift for four or five years

back in the early 1990s and made some great cases. They took a

lot of guns and drugs off the street, and made a lot of arrests doing it.

Ken misremembered a line from an old movie, Next of Kin. The

line was, "Yeah, we made a mean pair too." The brothers were

talking about the fights they had been in, and one said, "We had

some doozies," to which the other brother replied, "Yeah, we

made a mean pair too." However, Ken always thought he said,

"Together, we made a mean pair of two," and Calpin and Ken did.

The names Calpin and Driscoll were legendary from those days.

![]()

POLICE INFORMATION

Copies of: Your Baltimore Police Department Class Photo, Pictures of our Officers, Vehicles, Equipment, Newspaper Articles relating to our department and or officers, Old Departmental Newsletters, Lookouts, Wanted Posters, and or Brochures. Information on deceased officers and anything that may help preserve the history and proud traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to honor the fine men and women who have served with honor and distinction at the Baltimore Police Department. Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History, Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll

Patrolman Anthony H. Maliszewski

Proudly written and submitted by his daughter, Mary English

My father was born on May 31st, 1914. Julian and Marianna Maliszewski were his parents, and he was their third child out of ten. Both of his parents were immigrants from Poland. Although they lived in villages only a few miles apart in Poland, they met in Baltimore and were married at Holy Rosary Church on S. Chester Street.

My father attended Holy Rosary School and finished the 8th grade. Back then, children were expected to help with the family income, so they went to work. The 1920 census shows him working in a drug store. At some point, he went to work for Budeke’s, which was located on Broadway in Fells Point. I know he did deliveries because that is how he met my mother, Frances. She worked as a secretary, and he made deliveries to the company she worked for. They married on November 21st, 1940, at Saint Michael’s Church on Lombard St. and Wolf St. Interestingly, it was a Thursday and Thanksgiving. They had five children: Anthony in 1942, Robert in 1944, James in 1945, Michael in 1950, and me, Mary, in 1955.

He joined the Baltimore City Police Department in 1942 and was stationed at what I think was the Northeastern District substation on Belair Road. Back then, patrol cars had two officers, and I remember his partner, Adam Grabecki. It was also a very different time, and my father never actually shot his gun. He did a lot of community interaction and was regularly requested to play Santa Claus at local churches. As his children got older, he was always volunteering to switch with fellow officers who had young children so that they might enjoy Christmas morning with their little ones.

I believe it was around 1962 that my father was stationed at the old Pine Street Station, where women and juveniles were kept. He was wonderful with the children and babies; he used to take great care of them. I’m guessing this was pending social services taking the children when their mothers were incarcerated. He was given the nickname “Yardy” back then and worked as a "Turnkey,” if I remember correctly. When the Pine Street station was closed, he went to the Northeast District Police station on Argonne Drive. It was from there that he retired in August of 1972, after 30 years of service.

When my mother retired, they were able to do some traveling, and they were lucky enough to celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary in 1990. My mother, Frances, passed away in 2000, and my father was not quite the same after. They had been married for 60 years. He followed her in 2003. My father instructed me to call a specific number at the Police Department when he passed, and I was very thankful that I did. The person I spoke with knew my father and was kind enough to ask if we needed pallbearers for his funeral. He arranged for police cadets to be his pallbearers, and there were also police officers standing beside their cars on the route to the cemetery. So many attendees told me my father would have been so proud of their honoring him in this way. He was very proud of his service in the Baltimore Police Department. On this page, you’ll find some pictures, newspaper clippings, and copies of certificates we have saved over the years. I searched newspapers.com to try to find better copies of the clippings we had. I have also enclosed copies of letters sent to the family offering condolences when he passed. There is a letter from Kevin Clark, who was then the acting commissioner, as well as a letter from Michael Hayden, the director of the National Security Agency. My brother, Robert, worked for NSA; there is also a tribute to my father from oldest grandson, James, who wrote on his blog.

![]()

POLICE INFORMATION

We are always looking for copies of your Baltimore Police class photos, pictures of our officers, vehicles, and newspaper articles relating to our department and/or officers; old departmental newsletters, old departmental newsletters, lookouts, wanted posters, and/or brochures; information on deceased officers; and anything that may help preserve the history and proud traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to honor the fine men and women who have served with honor and distinction at the Baltimore Police Department. Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History: Ret Det. Kenny Driscoll

12th Pennsylvania Infantry

1861: Charles F. Porter to Jane Porter

February 19, 2024 Griff Leave a Comment

The following letters were written by Charles F. Porter (1822-1872) who served as a Lieutenant in Co. C, 12th Pennsylvania Infantry (3 Months). Charles was mustered into the service on 25 April 1861 and mustered out on 5 August 1861.

After training several weeks at Camp Scott in York, Pennsylvania, the 12th Pennsylvania received their uniforms and equipment on 19 May and then relieved the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment along the Northern Central from the Pennsylvania–Maryland border to Baltimore on 25 May; the Northern Central provided an important connection between Harrisburg and points further north, Baltimore, and Washington, D. C. to the south. Regimental headquarters and Companies I and K were located at Cockeysville, while the remaining companies were spread out along the railroad; it was assigned to the 3rd Brigade of the 1st Division of Patterson’s Army (the Department of Pennsylvania). Though the regiment had initially been thrilled at the news of its movement, it quickly found guarding the railroad monotonous, and desired action. The regiment did not train as a unit while guarding the railroad due to its dispersed positions, although Companies I and K conducted daily drill.

Camp Scott in York, Pennsylvania, May 1861

Letter 1

Little York

York County, [Pennsylvania]

April 26th 1861

My Dear Wife,

We left Harrisburg yesterday, after being mustered in to service, and got here at 10 o’clock all. well, and in good spirits, and found nothing ready for us but will be in camp today. We do not know when we leave, nor do we know where we go to. We were only allowed to take 64 men out of 90. John Moffitt was discharged. They would not take him and I think from what I see of the service, he could not stand it. We were not allowed three lieutenants so one of us had to leave. We drew lots who should leave and Charles Lewis had the leave straw, so I am 1st Lieutenant and Mr. [William S.] Collier is in my place. So I have went up one grade and I may still, if things go right, go still higher. When you write, direct to Lieut. Charles F. Porter, care of Col. David Campbell, 1 Second Regiment, Western Brigade, Pennsylvania Volunteers, and it will be sent to him and I will get it.

Poor Kate, how does she get along? Tell her to be a good girl and kiss her.

My uniform is spoiled with the rain on the day we left. The cloth was not sponged and it shrunk nearly off my back. 2 I have sent to him for another, and I wish you would go and see him, Mr. Frowenfeld & Bro., in the Bank Block on Fifth Street upstairs and see about it. 3 And tell him to sponge the cloth. Write soon. I shall have to close for my time is up. May God bless you and take care of you. Kiss Kate for me and tell her to kiss you for me. Keep up your spirits for there is hope for us all. God bless you all is the prayer of your affectionate husband, — C. F. Porter

P. S. Tell Mrs. Knox, John is with is and well.

1 David Campbell recruited the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry (64th Regiment) in September 1861. He had previously commanded the Twelfth Regiment in the three months’ service, and previously a militia company of considerable repute in the city of Pittsburgh.

2 Sponging is a textile finishing process that involves the use of steam and water to moisten and condition the fabric before it is cut and sewn into garments or other products. The process can improve the quality and appearance of the fabric, making it easier to work with and enhancing its overall performance. Sponged wool made for better uniforms to prevent shrinkage.

3 Frowenfeld & Bros., wholesale clothiers, was located on 31 Fifth Street. A notice appearing in the Philadelphia Inquirer on 21 May 1861 alleged that Frowenfeld & Bros. defrauded the state by supplying Pennsylvania regiments with clothing of such poor quality that the soldiers actually suffered.

Letter 2

Camp Scott

York [Pennsylvania]

May 2nd 1861

My Dear Wife,

I wrote a letter to you on the 30th of April to send by Mr. D. Thompson but today he said he was a going to stay with Quinn’s Company so I send it and this by Mr. William Alexander who leaves tomorrow morning and he can give you all the news about the camp. I am well and hope to God you and Kate are the same. I do not know when we leave, nor can I find out, but I do not think it will be long before we take up the line of march, and then God protect us all.

Tell Kate I enclose the cockade for her. We all wear them in camp. I wore it myself. Tell John Knox’s mother he is well and in good spirits, and in good health. He sends his love to her and his little girl. Tell James Irvin when you see him to write to me. He has wrote others in the camp but not to me, so you can jog his memory about it. Tell Mr. Parks I will write to him the first spare moment, I get, and give him my best respects, and kind regards. Also to his family. And tell him I think very often of him. Have they got a letter carrier yet at the Post Office.

Our whole time is now taken up in drilling. Company drills from 6 to 7 o’clock, then breakfast, then drill from 8 to 9 o’clock, regimental drills from 10 till 12, then dinner, the company drills till 2:30 o’clock, the Brigade drill till 5 o’clock, supper at 6 o’clock. So you see we have but little time to ourselves. Mr. Alexander can tell you all when he delivers this. He don’t like camp duty much and won’t enlist so he comes home. He is wise in so doing, for a soldier’s life would not do for him. He is too slow. Everyone has to take care of himself here and one who does not, it not fit for such a life.

But I must close. He will soon be for this letter and I must go to drill. So no more. Kiss Kate for me and tell Kate to kiss you for me. May God bless you all is the prayer of your affectionate husband, — Charles F. Porter

Letter 3

Camp Scott

York [Pennsylvania]

May 11, 1861

My Dear Wife,

I received your welcome letter and box of eatables by James Irvin this morning and I am thankful for them, for they are very nice, but I am afraid you have spent your money for me, and it will take too much from you. I would rather you would keep all your money for your own use. It is a mistake about us officers having nothing to eat. We fare well for we have to buy our provisions, but our men do not get enough to eat, for three rations does not satisfy them. They do not get enough of bread to eat. They are not any better off than when they [left] Pittsburgh. We got them 69 baskets and haversacks and that is all. One of Neptune Engine 1 members came here yesterday and brought some twenty blankets which were sent to them by members of their company which was a God send to them, and I do not know when we will get them rigged out but I hope soon.

Now don’t you worry about me. I am an officer and have all the privilege my rank entitles me to. It is only the common soldier who fares hard. I have endeavored to treat the men as men as far as my power would permit but I am only 1st Lieutenant. The less I say about the Captain, the better. But I can say without any boast, there is not one man in our company who would not die for me, for they have so told me so, they say, and all who have come in contact with me in my line of duty. I am the best posted soldier on the ground. Keep this to yourself for people would say I am bragging about myself, but so it is.

I will write you again by James Irvin. He leaves here on Monday morning.

We have no news here. All the news we get is by the papers we get. Everything is kept dark from us, but so it is. I expect we will leave here soon. Tell Mrs. Knox [that] John is well, and sends his love to all his folks. No more at present, but will write by Irvin. Give my respects to all the clerks that call from the Post Office to see you. Give my love to all your folks, one and all. Now take good care of yourself and Kate. God bless you both. Give my respects to Mr. Parks and family and tell him I will write as soon as I can get time. Now Jane, be careful of yourself. Kiss Kate for me a thousand ties, and the same for yourself.

God bless you all is the prayer night and day of your affectionate and loving husband, — Charles F. Porter

1 One of the oldest Fire Companies in the City of Pittsburgh.

Letter 4

Camp Scott

[York, Pennsylvania]

May 15th 1861

My Dear Wife,

I take this opportunity of writing you these few lines. I am well at present and hope you and Kate are both well. I suppose you have heard how they have tried to make us enlist for three years, but failed. Our regiment won’t enlist for three years but our men are willing, when our three months are up, to go three more months—or six months—but not for three years. So you may rest easy about me for I will not go myself in the same situation that I have. It must be something better. But do not think for one moment that I will enlist for three years, so rest easy about it.

I expect we will leave here in a few days for we are getting equipped as fast as possible. As soon as we get overcoats and knapsacks, we will be full equipped, and then I expect we go to Washington City and I hope to God we will soon return with honor and peace to our beloved country and our glorious flag long may wave.

I have not seen John Quinn, only on parade, with 13th Regiment [commanded by] Col. [Thomas A.] Rowley. So he is well. Tell Mr. Park I will write to him soon and give him my best respects and to his family. The 12th Regiment is the crack regiment on the ground so we have worked very hard to drill the men. I have very hard work of it for all the leaving to drill falls on me. [Neither Captain John H.] Stewart nor [2nd Lieutenant William S.] Collier knows very little about drill, but I do it for the good of the men, if if they did not know how to drill, it would be a bad show for us.

Give my best love to all of your family and best respects to all friends. Also to Mr. Moffitt. And tell him he may be glad John did not come for it would have been his death. He could not have stood it. John Knox is doing better. He sends his love to his mother and child. Kiss Kate for me and tell her I. hope to see her soon.

Now Jane, take good care of yourself. May God bless you and Kate is the prayer of your affectionate husband, — Charles F. Porter

Letter 5

Camp Scott

[York, Pennsylvania]

May 19, 1861

My Dear Wife,

I received your kind and welcome letter yesterday by Mr. Neeper and was happy to hear that you were both well. I am well at present and hope you and Kate are the same. Tell Kate I was much pleased at receiving her card and hope she will continue to improve her time. I gave me great pleasure indeed.

It is raining now and has all the appearance of raining all night. There is no news here at present. We do not know when or where they send us. They have not fixed the three years enlistees in our regiment yet. Some company will have 40 men to go, some none, some two, &c. They tell us if we don’t enlist for three years, the people of Pittsburgh if we return in three months, will turn the cold shoulder to us and treat us with scorn. But let them. We came here to do our duty and if they give us the chance, we will do our duty. There are all sorts of rumors here as to what they will do with us. We received our overcoats yesterday—grey cloth. Our men are nearly equipped now and seem better contented.

You are mistaken as to our pay being reduced. My pay is 50 dollars per month, with rations. Without rations—or in other words, find ourselves (for they won’t give us rations)—is $103.50 per month, (that is they pay us for our rations) but I fear we shall never receive any pay. I may be mistaken, but they will do anything now days. But God’s will be done.

I received a letter from Pap last week and one from Julia. They are all well. He and Sarah Ann sends their love to you. Col. Campbell left here yesterday for Pittsburgh. Expect him back on Tuesday. Neagley has gone to Lancaster so we do not have any [drill] till they return.

One Frank Grant of Company C, 13th Regiment, Col. Rowley, was drummed out of camp today. He cut some days ago one of his comrades and he was tried and found guilty and drummed out today. It was a sorry sight. He felt it keenly. Poor fellow. Whiskey was at the bottom of it. If the men would only leave strong drink alone, they would do well. In our mess—that is us officers, we neither drink it or have it in our quarters. I wish I could say the same of our men.

I saw [Lt.] John Quinn [Co. K, 13th Penn] yesterday. He is well. John Knox is doing first rate now. Looks well. He sends his love to his people. Give my best respects to Mr. Parks and family. I hope they are well. Give my respects to all inquiring friends. Give my best respects to any of the clerks that you see from the post office, and through them to all in the office. Give my best love to all of your folks, and you be sure to take the best care of yourself and Kate, and I shall do the same to myself.

If you see James Irwin, give him my best respects, to him and family. There is a great number of Pittsburghers here today. Some I got a chance to speak to and they said everything is still very dull yet and I am afraid it will still be duller yet. But I hope for the best. We have a hard days work tomorrow in the way of drills. They give us plenty of work to do, and it is very hard work to drill 60 raw recruits. But they get along finely and the Major complimented me in their drill yesterday. We do as well as some of the older companies.

Now Jane, keep up your spirits and take care of yourself and don’t send any more eatables. We have enough and can get enough at any time. We live very plain for when we leave here, we will have to come down to hard grub and then it will not sit so hard on us, and in fact, we are better on course grub for camp life is a hard life. It shows up human nature and it has showed up some of the officers here, and when they get home, they will be yet to hear of it.

No more at present. Give my love to all. May God bless you and Kate and all your folk. God bless you is the prayer of your affectionate husband, — Charles F. Porter

Letter 6

Camp Scott

York, York County, Penn.

May 24th 1861

My Dear Wife,

I received yours of the 22nd and was glad to hear you and Kate are both well. I’m in good health. You said I must be swelled. It is not so. I had my overcoat on that day for it was raining and I was very dirty and wet. But my last picture was taken when I was fixed up so you can judge whether I have got so fat. I am a great deal stouter than when I left home.

But now for news. Our regiment leaves here. The Left of the regiment leaves today; the Right I expect will leave tomorrow, but I am not sure. Our company is on the Right Wing. The Grays [Co. B] and City Guards [Co. K] on the Left Wing. They are packing up their things now. They take six cooked rations and 40 rounds of ammunitions, so they must expect hot work. The Flying Artillery left this morning. We will commence to pack our things this afternoon so as to be ready at a moment’s warning. The Boys are in great glee for they think we will have a fight soon, and I think the same. So pray for us and our cause. God be with us and send us safe through all our trials.

I have not much time to write just now so please excuse this short letter. Give my best love to all of your family, and to Mr. Parks and all enquiring friends. Kiss Kate a thousand times for me and tell her to kiss you the same for me. Now keep up your spirits and be of good cheer, for there is a sweet little cherub that sits up aloft that will take care of me. God Almighty, bless and protect you both. Take good care of yourself and what whatever you want for yourself and Kate. As soon as I can write to [you] again, I will do so. But you must write and direct your letters as I sent the directions to you and I will get them safe. God bless you Kate, and all of you. May we soon meet once more. God bless you both.

Your affectionate husband, — Charles F. Porter

P. S. Tell the letter carrier he is getting fooled by the people. They tried the same on me. He must use his discretion in trusting, but he is too slow and not sharp.

Letter 7

Mellsville, Maryland

May 26th 1861

My Dear Wife,

We left York yesterday at 1 o’clock and at the present time are quartered at Mellsville three miles from Baltimore. The regiment is strung along the railroad guarding the bridges. The Greys are 27 miles from us on guard, and at every bridge along the road we have left one company except at this place where we have three companies—the Blues, our company, and the Washington Greys. Col. Campbell is with us. We relieved the 1st [Penn.] Regiment who goes to Frederick City road, four miles from here, to guard the passage to Harpers Ferry to stop all supplies from the rebels.

This place is very healthy and pleasant and the people very friendly. We are within sight of Fort McHenry from a high hill in our neighborhood so we are in the enemy’s country now. We have to keep a strict guard for fear of a surprise.

We are all in good health and good spirits. Knox is well and so is Bell. He never was sick. Now don’t feel uneasy about me for I think this point is as far as we shall go—at least for some time. And maybe we shall go no farther for we are all three months men. Now take good care of yourself and Kate, and do not let yourself want for anything for we will get paid for we are in the government hands now and not the State of Pennsylvania. I shall not get to write so often to you now for there is no Post Office here and we will have to wait till someone goes to York. The Asst. Quarter[master] leaves here for York at 3 o’clock so [I] send this letter by him to put in the office there. You must still direct your letters the same and they will be sent to me. Now you must excuse this short letter for it is near the time the train will pass here which he goes on, so I must close.

Now pray take care of yourself and I will of myself. I like this place better than Camp Scott. We are better quartered here and have better quarters here and have better water. We are quartered in a large new building intended for the distillery. The only thing that will be hard on us is our guard duty for we have to be very watchful. I am in very good health.

Did Lieut. [William S.] Collier give you my last picture or did he send to you? We left the next [day] after he left for home. We sent for him right away so he may have not had time to call on you, but let me know whether you got it or not.

Now give my best love to all of your folks, and to Mr. Parks, and all enquiring friends. How does Kate get along now? Tell her to kiss you for me and kiss her for me. No more at present. May God bless you both is the prayer. of your affectionate and loving husband, — Charles F. Porter

P. S. Now don’t feel uneasy if you do not hear as often from me as you have for I have not the means of sending letters as often. But you must write as often to me and every chance I get I will write to you.

Letter 8

Mellsville near Baltimore

June 4th 1861

My Dear Wife,

I received yours of June 1st and was happy to hear you and Kate are well. I am very well at present. It is raining today and I can answer your letter today but I do not know how soon I can send it, but will send it the first opportunity. I was very much pleased to get Kate’s few lines. She has made great progress and I hope she will still continue to do so.

Last Saturday morning ]1 June 1861] our company received orders to march with one days provisions to go to a town 12 miles from here to take a lot of arms from a company of rebels. The town was called Toucheytown [?]. We marched at 10 o’clock, went as far as the Relay House where we were joined by Companies I, K, and G—four companies, 172 men under Major [Alexander] Hays. After a toilsome and hard march, for it was very hot, we reached the town. We came very unexpectedly on the town. We took up our several stations. I was stationed with one platoon to the cross roads with orders to leave no [one] pass out and to join the command at a given signal. The rest of the companies was placed around hte town. In less time than I can write it, we had the town surrounded. The Major took a detachment of the City Guards, Co. K, and searched for the arms. We got 25 new rifles after a short search.

While I was guarding the roads, and old gentleman came up to me and we had a long talk. He was a strong Union man. He seemed so happy to see some of the United States soldiers once more. He pointed his house out to me. It had the Stars and Stripes waving over it. He said there was a great many rebels there and one company of soldiers which was to drill that [day but] on account of our presence, he said he expected they would put off their drill. Whilst talking to him, I seen some running in the town and received the signal to close. We dashed off at double quick with a shout from our men for we thought it was a fight, but when we got there it was only to guard the arms. So I never seen the old gentleman after.

We stacked arms by companies in the large open square in the center of the town while them men filled their canteens with water for our return home. I staid by our arms and kept half of our company with me for I did not like the looks of things whilst the rest of the officers and men scattered about. When all at once, I hear a pistol shot over at the Hotel where all of our men and officers was. Everybody rushed to see but us. I ordered our company to fall in which stopped them as if a bomb shell had fall amongst them. The reason I done so was to guard the stacks of muskets which the other companies had left unguarded. I was afraid it was got up to get our muskets and then we would have been at their mercy. But they did not like the looks of the Fireman’s Legion [Co. C], but the alarm was false. It was the accidental discharge of a pistol in the hands of one of Captain [George W.] Tanner’s Company [I]. It came near killing Glock Bonnoffer [?] if he had not jumped aside. As it was, the powder burnt his pants and the ball just grazed his sword.

After a short rest, we took up our march for quarters which we reached about 5 o’clock. So ended our first expedition. That evening the train brought down 49 muskets which was captured by the Greys under Capt. [John S.] Kennedy the night before. And Sunday afternoon, the Blues were sent out some three miles in the country to take some powder from a farmer’s house, but they could not find any there so they had their march for nothing.

We are receiving notice most every day where arms are hid, but do not place much confidence in them. But when sure of it, we go and take them. We had a shocking accident on Monday morning about 3 o’clock. A large freight train from Baltimore passed me at quarters. (I was Officer of the Day) and in about fifteen minutes after one of the guards on the line of the road came running in for the doctor for one of Company E had been run over by the train (it was the Washington Greys) and to hurry up. I woke up the doctor and the alarm woke up all. hands who started up the line. After some time they returned with the poor fellow on a litter, very badly hurt. His head is dreadfully cut and his back and breast hurt. He had sat down on the rail of the road and feel asleep when the train came up and struck him. Poor fellow. He will, I fear, hardly get over it, but it will be a warning to the rest for to sleep on post now is death. But if he gets over it, nothing will be done to him.

Since my last letter, we have lost one of our men, John J. Werling. He died at York. We left him sick there when we left. Poor fellow. He was a fine young man. We got the news yesterday. He died on Sunday morning. It was received by the company very sorrowfully. The 13th Regiment paid him all the attention they could and escorted his remains to the cars which will ever be remembered by the 12th and our company. His body has reached Pittsburgh before this. I hope they will give him a soldier’s funeral for he deserves it as much as if he had been killed in battle, for if he had lived, he would have fought nobly. May his ashes rest in peace and I hope he is in a better world.

Now you must take care of yourself and Kate and so not neglect to get anything you want. I am sorry to hear the bird is sick. I hope he will get over it for I would be sorry to hear he had died for he cost too much. If you could sell him now, it would come in good time for you. Tell Kate I will keep her letter to me till I come home and give her a kiss for it for me. Captain Stewart and Lieutenant Collier sends their best respects to you and Kate. Give my best respects to Mr. Parks and family and to James Irvin and tell him to write to me. Also give my respects to all inquiring friends and give my best respects to John Roberts and tell him to give my respects to all of our old clerks in the Post Office. Give my best love to all of your folks. Write as often as you can for nothing is so welcome as a letter from you. It cheers me whenever I receive one.

I do not know when we leave here but when we do, it will be at very short notice, like our other orders. There is all sorts of rumors of battles and fights and when and where we go to, but nothing certain. But I expect when we do leave, it will be for Harpers Ferry, but wherever it will be, I will try to do my duty as well as I can. You need not fear for me. I am not one of that kind to rush into danger unnecessarily, or volunteer unnecessarily, but will go where ordered.

Kiss Kate a thousand times for me and tell her to kiss you for me. Write soon and I will answer as soon as possible. No more at present. May God bless you both is the prayer of your affectionate husband, — Charles F. Porter

Letter 9

Letter 9

Mellsville near Baltimore

June 10th 1861

My Dear Wife,

I received yours of the 5th on Saturday and I was very happy to hear that you are both well. I am in very good health at present. We had a great deal of rain last week but it is clear and very pleasant now. There is nothing new to tell you at present, but any amount of rumors. We are expecting orders to leave here every moment, but where to we do not know. Some say Harpers Ferry and others say the City of Washington, but God only knows when or where we shall go to. But I think we shall be here for some time yet, and I think when we go, it will be to the City of Washington to help the guard it from the rebels, but cannot say so for certain, but that is my impression.

Col. Campbell has left here with the band and gone to Cockeysville. There is only two companies of [our regiment] here at present. The Blues have gone up to the place where the Greys were. The Greys are at the Relay House, three miles from us, in place of Capt. Cooper’s Company. The City Guards are with Campbell, and the Zouaves at Cockesyville. As there is only two companies of us here, we have still harder guard duty to do, but we all stand it very well.

We have a report in the regiment here that Campbell is to be a Brigadier General and S. W. Black is to be Colonel of our regiment. I cannot vouch for the truth of it, but that is the rumor here, and that the regiment after the three months are up is to [be] filled up and go for three years. I know for certain that the regiment has been offered by Campbell to the Secretary of War for three years, and has been accepted—that is, after out three months are up and all the three months men can [either] reenlist for three years or go home at the end of their present term of enlistment, and then they will recruit to fill up the regiment. I think and am sure there will be very few who will reenlist out of this regiment. They are dissatisfied with their treatment and their officers but would nearly all of them come back in other companies.

We are not in Gen. Negley’s Brigade now. We are not in any. We are on detached service. The Secretary of War sent officers to York to Gen. Kiem for a good regiment and one that could be trusted to guard this road. we were sent as the only regiment he could trust—so much for a good name. All around here and at Washington we are called the crack regiment of Pennsylvania. So they have a good opinion of us, and I say it without any bragging that we are the best drilled regiment for the time we have been in service of any in the state. We will drill with any of them, and our company is as good at drill as any in the regiment. We expect some trouble about here next Thursday, it being election day. They expect plenty of rows in Baltimore and all the troops are ready for any attack that may be made on us or the citizens which stand for the Union. God help them if they do commence on us. Baltimore will be laid in ashes for we can do it, for Fort McHenry commands the whole city and we have troops all around the city.

I enclose a secession badge which will be a curiosity to you as you never saw one. They are afraid to wear them openly here for if caught they would get in trouble.

How is everybody? Give my best respects to Mr. Parks and family, and to Jim Irvin, and all enquiring friends. Give my best love to all of your folks and tell Kate I have her letter safe. I wrote to you last Monday the 4th of June and have got no answer to it yet. Tell Kate to kiss you for me, and you to kiss her for me. How is the bird? How do you get along? I hope you take good care of yourself. Now be sure to do so and tell Kate to be a good girl till I come home. You must excuse this letter for I have nothing to write new to you for we get very little news here.

Tomorrow our quartermaster come to give the men their rations and then we will get some news. No more at present. I remain your affectionate husband, — Charles F. Porter

Letter 10

Letter 10

Mellsville near Baltimore

June 17th 1861

My Dear Wife,

I received your letter of the 12th inst. on Saturday and was happy to hear you are both well. I am in excellent health at present. I am sorry to hear you do not get my letters regular. I answer every one of yours as soon as possible and send them always by the first opportunity so do not feel uneasy about it for delays will happen.

I now must tell you about a very painful and shocking affair which happened here on Saturday evening near our quarters, and to members of our company. We have for some three or four days taken notice that some of our men were inclined to meeting and we were watching them very close, unbeknownst to them. On Saturday evening, just at guard mount, word came into quarters that John Knox, Joseph Davis, Robert Bell (alias Loafer Bell), and John W. McClay were drunk and raising a fuss with everybody. I was just on the point of marching off my guard (for I was on first that night) as the word came. The Captain wanted to send some of my guard but I told him I could not spare them, but to take some of the second relief. I marched my guard off to our post and in about an hour I heard some heavy firing in the neighborhood of our quarters. I expected something had happened and kept my men at their posts for I knew if wanted, we would be sent for. It seems the Captain sent the 1st Sergeant to get them to come in. He went after them but they would not come and made an attack on him with knives. He had to fly for his life. The Captain then sent a sergeant and two men with muskets but they could do nothing. Bell then rushed on the guard and took one of their muskets from them. The guard came back and reported. The Captain then ordered ten men out under the Sergeant and the orders were to bring them dead or alive. They marched off and when they arrived near the place where they were, Bell ordered them to halt. The guard still advanced and the Sergeant ordered the four men to give themselves up but they refused and defied the guard and said they would not be taken alive. As the guard came near them, Bell fired his musket at them and the rest fired their revolvers. The Sergeant ordered the guard to fire. They obeyed orders and fired. Bell was killed on the spot having three balls through him. 1 John Knox was very badly wounded in his right arm. He will lose it. Joseph Davis and McClay gave themselves up to the guard and brought to quarters along with Bell’s body.

Word was then sent to Col. Campbell. He came down yesterday morning. He examined into the affair, preferred charges of mutiny against Davis, Knox, and McClay, and ordered them to be taken in irons to Fort McHenry. I was ordered to taken them there under a strong guard. I took Davis and McClay. Knox, the doctor said, could not be taken till today (he was send under guard today). We got a covered wagon and put them in and took them to the fort. I delivered them safe there with the charges against them and they will be tried tomorrow at Fort McHenry, and according to the evidence brought against them, depends their fate. If found guilty they will be shot. I am sorry for them but they deserve their fate for they have escaped punishment so often they thought they could not be punished for anything they did. It will be a good effect on the rest of the men for now they see bad content will be punished and that promptly. The men say they deserved their fate and are quite orderly and quiet. It does not seem like the same company. We have two more men to punish this afternoon for theft. They have been under guard for 48 hours without rations. One is a sergeant, the other a private, both brothers—James and John Fowler. The one that is a sergeant [will] be reduced to the ranks as a private this afternoon and then I hope we shall never have the disagreeable duty of punishing any more of our men and I think we will not have it to do, As soon as I ascertain the fate of those men, I will write you word.

How does old Mr. Parks get along? I hope he does not suffer so much. Poor old man. Give my best respects to Mr. Parks and to all enquiring friends. I do not know how long we will be here. They talk of changing the position of the different companies on the line but the regiment will still be stationed along his road. I expect if they do change the position of the companies, we will be placed up at or near the other end of the road but I would rather not be moved for we are in very good quarters here, and a healthy place, but we will have to obey orders, and go where we are sent to. I think of going to Baltimore with Lieut. Collier some day this week and take a look at the city and see some of my old friends amongst the Philadelphia regiment stationed there.

Tell Kate to kiss you for me and you kiss her for me. Give my love to all of your folks and tell them to take good care of you, and you must take good care of yourself, and get anything you want. We will soon be paid off, so they report here. But I would rather wait till we get discharged and get it all in a lump. It will do more good then. No more at present but write often. May God bless you both is the prayer of your affectionate husband, — Charles F. Porter

1 Robert Bell’s service record indicates that he survived his stint in the 12th Pennsylvania but we now know that isn’t true. There were several people with that name living in Pittsburgh in 1860 but I believe he was either the the grocer and liquor merchant at 237 Liberty Street or his son. He was boarding at the Scott House in Pittsburgh at the time of his enlistment. His enlistment papers record his birth year as 1828 so he would have been @ 33 years old.

Letter 11

Mellsville near Baltimore

June 22nd 1861

My Dear Wife,

I received Aunt Betsey’s letter yesterday afternoon. I am more than happy to hear that you have got over your troubles so well and happy to hear you are doing so well. It takes a great weight off of my mind to think you and the child are doing well. Tell Kate to kiss her brother for me and we will name him when I come home. How do you like Doctor King? I hope he will pay proper attention to you and you must take the best care of yourself.

I had to stand treat to our officers on the receipt of the news. They call me Pap now here as it is the first birth belonging to the regiment. They claim him as one of the 12th so take care of yourself.

I wrote you all the facts relating to that sad affair. The Dispatch has the best and truest account of it. Tell Mrs. Knox she has the sympathy of all of us and it would do no good at present for her to come on for I don’t think they will be so hard on John. 1 He has not been tried yet and will not be for some days yet for he is not fit to leave the hospital to be tried. He will not have to have his arm taken off but they say it will be always stiff. But if when tried, I find that her presence will be of any service to him. I will send her word to come, so tell her. [Joseph] Davis, I think will be shot or hung. [John W.] McClay will not be dealt so with, but God knows what their fate will be for we have not heard yet what it will be but expect to know in a day or two, and will write as soon as we do receive the news.

Two regiments of soldiers passed here this morning. Two more to pass this afternoon. There is 20,000 men to pass here in less than ten days for Washington. The 13th [Pennsylvania] will pass here in a day or two for Washington. We will be kept here to guard the road so they can pass in safety over it, for if the road was not guarded, they would burn the bridges and no troops could pass to Washington. I wish our time was up, or else they would send us to Washington to help defend it for they expect the city will be attacked, but they think we can do more service by guarding the road so troops can pass. It is very hard service, but we all keep in good health and spirits.

We have not seen Col. Campbell for a week and our Lieutenant Colonel is at preset in Baltimore sick, so we have to take care and be very watchful—so be it. Give my best respects to all. enquiring friends. Give my love to all of folks, and tell Sarah Ann to take good care of you, and not give you veal cutlets and custards to eat till you are well. Tell Kate to kiss you and the baby for me, and you kiss her for me, and tell her to be a good girl. No more at present. God bless you all is the prayer of your affectionate husband, — Charles F. Porter

1 John George Knox (1821-1904) not only survived his three month stint in the 12th Pennsylvania Infantry, he reenlisted as a private in the 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry and served another one and a half years. He was married to Mary Anna Jones (b. January 1821) in 1850. His mother was Julia (Biggs) Bougher. In April 1864, after Knox was discharged from the 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry and had returned to his job at Bailey, Brown & Co.’s rolling mill, an officer came to arrest Knox for stealing a government horse when he left mustered out. It was Knox’s mother, Mrs. Julia A. Bougher that paid the officer $120 to clear up the matter. It later turned out that the officer had no authority to make the arrest and the officer (named Scanlon) was arrested.

Letter 12

Mellsville near Baltimore

June 27th 1861

Dear Wife,

I received Aunt Betsy’s letter of the 21st day before yesterday and was very happy to hear that you are all well. I am very well at present. You must take the very best care of yourself and you get over your sickness very well. I received a letter from Mr. Park and one from James Irvin yesterday dated the 19th of June directed to Cockeysville and had been laying there ever since. Give them my directions to address letters to me and then I will get them.

There is no news here at present. We heard a rumor of our being discharged from the service in fifteen days—that is, all who will not go for three years. And if it is true, nearly the whole regiment will come home. There is a screw loose somewhere in the regiment for it is very badly managed and has been for some time, but do not say or let anyone see this part of my letter and when I get home, I can give all the facts and show up some of them for I know a soldier’s rights better than they do.

Tell Kate the baby is not named yet but we will name it when I come home. Tell her to take good care of it and kiss it for me. Is she a good girl? I hope she is and will continue so. I fancy I see her now as she came down the street to meet me. God bless her.

I expect I shall be sent to Fort McHenry tomorrow to see Dais and the rest of our men to see if they want anything and to take them some clean shirts and see if I can find out what their sentence is for we have not heard what it is yet. But I have no pity for them. They deserve all they will get. You must make my excuses to Mr. Park for not answer his letter for I did not get till yesterday. If he had directed as you do, I would have got it in time. I have wrote to him today and to James Irvin. Troops are still passing here everyday and here we stand idle, and nothing to cheer us up for it is very hard to see so many troops pass on to Washington which have come in the service since we came. But it is not our faults. We are willing and anxious to go on, but there is something working against our regiment, but I thinkI can tell who it is. There is a day of reckoning coming. We have not seen Col. Campbell for near two weeks.

Give my best love to all of your folks and tell Sarah Ann to take care of you and that big baby. Give my respects to Mr. Park and all enquiring friends. Tell Kate to kiss you and the baby for me and you kiss her for me. You must excuse this short letter for I have nothing new to tell you. How does the bird come on? How does all the neighbors do? Do they come to see you any?I hope you will take care of yourself and soon be about. How do you like Dr. King? I hope he treats you well. He is a Mason. If he don’t, let me know. No more at present. May God bless you all is the prayer of your affectionate husband, — Charles F. Porter

P. S. Give my best respects to John Roberts when you see him.

Letter 13

Letter 13

Mellsville near Baltimore

June 29th 1861

My Dear Wife,