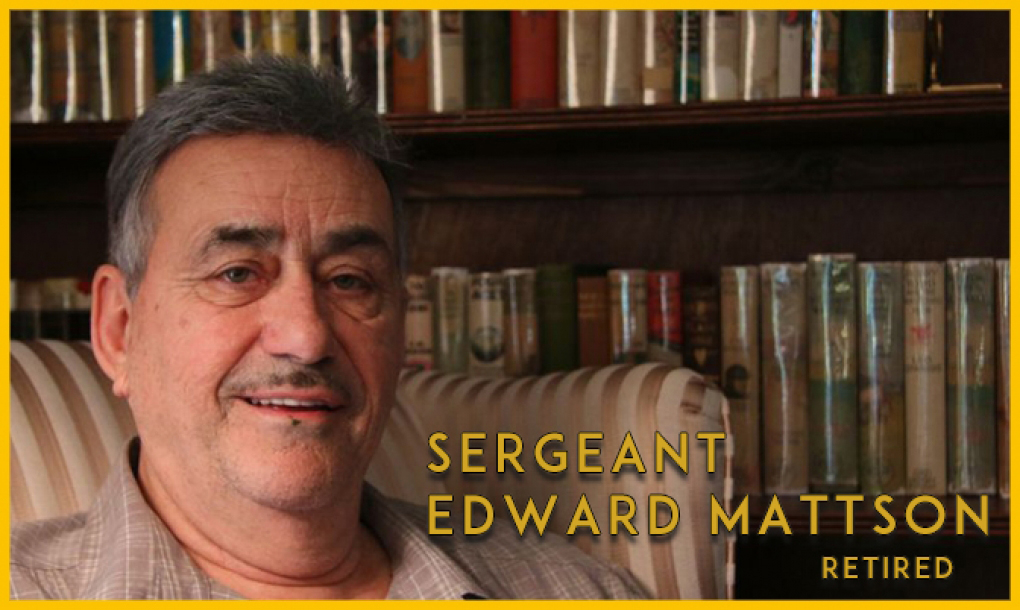

Ed Mattson

Sergeant Ed Mattson

Ed Mattson saw Baltimore's 1968 riots in person, and he watched the recent Freddie Gray riots on TV. He's still struggling to understand both.

He's canoed the Amazon from Peru to Brazil, wrestled a 20-foot anaconda, sumited mountains, and jumped out of planes. But there's one thing retired Baltimore police sergeant Ed Mattson hasn't done.

"I can never truly say I had a black friend. Even today."

Mattson sits and speaks at the kitchen table of the suburban Baltimore home that he and his wife have filled with 19th century children's books and antique oil paintings. His blazer hangs over a chair, an award on its lapel for his service during Baltimore's 1968 riots. As the Freddie Gray case and its aftermath have captured worldwide attention over the past several weeks, and the U.S. Justice Department has launched an investigation into Mattson's former department—the one that gave him that award and several others—Mattson has had much on his mind.

Recently, while grocery shopping, Mattson overheard a woman discussing the Freddie Gray riots. "She said, 'You know, I was never racist or anti-black, but I am now,'" Mattson says. "And I thought: Wow. This."

"I'll be truthful with you," he says, "I know guys that—is racist the right word? Or they just don't understand other people? I think the bulk of [officers] are honest, hardworking men that just go to work and do a job. I'm sure they don't go and say, 'Now today we're gonna go out and beat up a black guy.' I know this doesn't happen."

Thousands of protesters, in Baltimore and beyond, see the situation differently.

Mattson grew up in East Baltimore, born into a family of Italian factory workers. In the late '40s and early '50s, Mattson remembers, "Baltimore was like Mayberry." Everyone he knew lived in row homes, and the community had a small town feel. Policemen would threaten to tell your father on you, and kids intent on mischief would follow the lamplighter on his rounds through the neighborhood, turning off the gaslights he'd lit one by one. Both Mattson's grandfather and great-grandfather had been bootleggers and owned speakeasies during Prohibition. He came of age in an all-white neighborhood, graduated from an all-white high school, and served in a nearly all-white Marine Corps.

"We thought life for everybody was good," Mattson says. "It was America, man. The war's over, prosperity's here! But then came Lyndon Baines Johnson with his Great Society, where he wanted to help the downtrodden. When you're young, you don't see downtrodden." But after his stint in the Marines, Mattson came home to Baltimore, and started working as police officer—a white beat cop in primarily black neighborhoods.

"And I realized there were downtrodden people, there were people who didn't rise up," he says. "And I just used to look at it and say, 'Why is it like that?'"

Walking his beat in the early 1960s, Mattson says he did not perceive racial tension. Mostly, his job meant taking care of "humbles" (minor crimes, like loitering), and caring for people as he found them. He did see more of "the seamier side of life" than he'd noticed in his own neighborhood (more drug use, more public drunkenness), and he wondered why the black middle class seemed so small, compared to the white communities he knew.

"You went out on house calls, and there'd be two or three babies who have no milk," he says. "And you'd take it out of your money, out of your pocket, and buy them milk and bread. All the cops I knew did that."

But by the late '60s, the country was rapidly changing, and Mattson underwent riot training.

After Martin Luther King Jr. was shot, Baltimore exploded. By the third night of rioting, Mattson says, the police were under attack with everything from bullets to Molotov cocktails. "The firemen would come, and they would shoot at the firemen," he says. "And I thought: I could understand shooting at the police. I could really fathom that. But I couldn't understand [attacking] the firemen or the ambulance service, cause they are there strictly to help.

"It was just constant, it never ended: morning, noon, and night," he says. "All the food stores were burnt out. All the liquor stores were burnt out, the clothing stores. There's whole blocks of it that are gone. It looks like Berlin after we bombed it in World War II."

Of Mattson's nearly two decades on the force, those days meant the most to him.

"I saw incredible acts of heroism by guys I worked with—pulling people out of burning buildings, saving lives," he says. "The Baltimore Police saved Baltimore in 1968, there's no doubt about it. The Guard didn't do very much, State Police didn't. The Army came in; they didn't do it. We did it."

After the riots, Mattson went back to his old beat. But his daily foot patrol led him through a different Baltimore.

"People started hatin' each other," he says. "It was like a cloud hung over the city. It just seemed like the friendliness was gone—the trust—on both sides. I couldn't understand how they could burn our city down. And I guess they couldn't understand how I couldn't understand how they could burn our city down."

Last month's violence hit a much narrower swath of Baltimore, and community organizing within those neighborhoods has drawn broad support. Cleanup efforts have spanned racial and economic divides, and social media has helped to democratize protest and storytelling. Last week, CVS corporate announced plans to rebuild its burnt-out and looted locations.

Mattson says the recent riots are an example of what he thinks has gone wrong with policing since his time on the force. He and his wife watched as Mondawmin Mall was looted on live TV. "There were no police officers there," he says. "I said to my wife, 'Why aren't the cops responding to this?' And then we found out why: Cause they were told to stand down. In our day, that would've never happened."

But some things haven't changed. That video of Gray's arrest, where he's dragged to the wagon? "That's just normal," Mattson says. "Typical arrest. People fight you in battle, or resist you—you gotta strong-arm em." He also recognizes State's Attorney Marilyn Mosby's description of what investigators believe happened to Freddie Gray in the van as "bouncing."

"Should they have seat belted him in?" Mattson asks. "Probably. Should they have restrained him more? Probably. Should they have took him to the hospital? I'm sure they should have. But it didn't happen, and so you got this.

"And poor Freddie Gray's going to be made a martyr. But Freddie Gray's not exactly a martyr, you know? He's dead, is what he is. And you feel sorry for him. But also, I feel sorry for the other eight guys that got killed [in Baltimore] last week by gunfire, not by police officers."

Mattson spent his career on one side of the system. So he knows that system is flawed.

"Everybody's guilty 'til proven innocent, you know that; it ain't the reverse of that," Mattson says. "I tell my grandsons: 'Do not get involved in the criminal justice system. It's an oxymoron. There's no such thing as 'criminal justice.' Once you get your foot in, your whole body goes in. You're involved forever."

More than half a century after Mattson tried to keep the peace in his smoldering city, he has an idea as to why it burned, both in 1968, and again this spring. It comes down to one thing, really.

"They feel like they're left out of society. You want to make somebody mad? Ignore 'em. And that's what we've done."

POLICE INFORMATION

Copies of: Your Baltimore Police Department Class Photo, Pictures of our Officers, Vehicles, Equipment, Newspaper Articles relating to our department and or officers, Old Departmental Newsletters, Lookouts, Wanted Posters, and or Brochures. Information on Deceased Officers and anything that may help Preserve the History and Proud Traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

If you come into possession of Police items from an Estate or Death of a Police Officer Family Member and do not know how to properly dispose of these items please contact: Retired Detective Ken Driscoll - Please dispose of POLICE Items: Badges, Guns, Uniforms, Documents, PROPERLY so they won’t be used IMPROPERLY.

Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll