- Traffic Lights

Semaphore

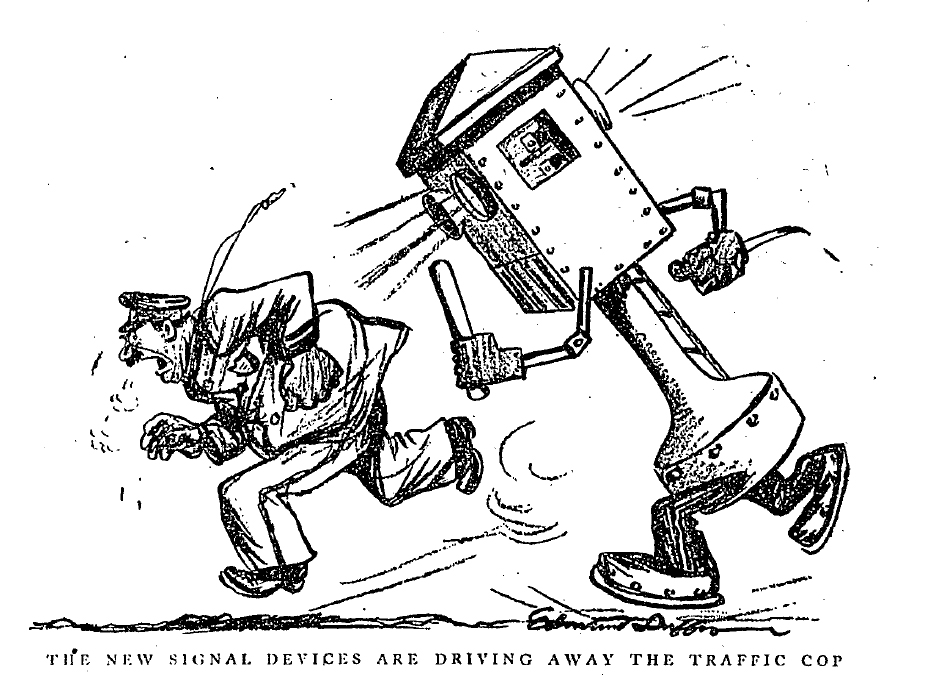

Traffic lights got their start with man operated Police Officer Posted Semaphore Devices, initially using what was known as the, "Go Go - Stop Stop" system, which was a Semaphore system of sorts, a pole with two intersecting signs, when turned one way it would say Go - Go and turned 90 degree to change it to saying Stop - Stop. Later they added a railroad lantern with Green and Red lenses to match with the Go Go - Stop Stop. There was also some debate as to whether we needed a two color or three color system, NYPD chiefs of police argued for a simple two color system, while Baltimore Police Commissioner Charles D. Gaither felt without a third color to warn traffic that Red was coming, we would end up with cars that were turning left stranded in intersections, likewise pedestrians left standing in the middle of a crosswalk. So he argued for and gained the support of Triple A to have an Amber light between the Green and Red light so as to give pedestrians and left turning vehicles fair warning. These colors would play an important role in another lighting system Commissioner Gaither was working on at the time, and that was his Police Call Box Recall Light System. Using spare nautical lighting, for the Recall Lights, his options were limited to Red, Green, White and Amber and Blue. He initially had Green and Red but feared from a distance an officer might mistake it for a traffic light, Not to mention around this same time, the automatic traffic light was being introduces, and in Baltimore like DC these lights were placed on the corner. To drivers new to this system, distinguishing between a traffic light, and a police Recall Light was often confusing. So while there were some Green and Red recall lights in the initial testing most of the red and green lenses were replaced relatively quickly. For a short time they used some blue lenses, but ran into issues of cost, at the time the Cobalt used to make blue glass was expensive and as such Blue was also eliminated. White, or Clear glass as it would have been was not even considered (though in a pinch would have been used with a colored bulb) They felt clear with a white bulb might blend in too much with street lights. So the color finally settled on was Amber. One might think it would provide the same issues found with Red and Green, except the Amber used was more of a Tan/Brown color whereas the Amber used on Traffic lights was as it is today most often described as Yellow. Over the years we had some Red lights from early in the program, and some Blue, but most commonly found is the Amber lens. Some old news articles wrote of the Green light, but in our research we found they were very early on and most if not all were replaced before the 1930s Anyway this page is more geared toward the traffic light and how it got its start here in Baltimore.

.

.

Semaphore

Baltimore's First Semaphore & The Traffic Officers that Worked Them

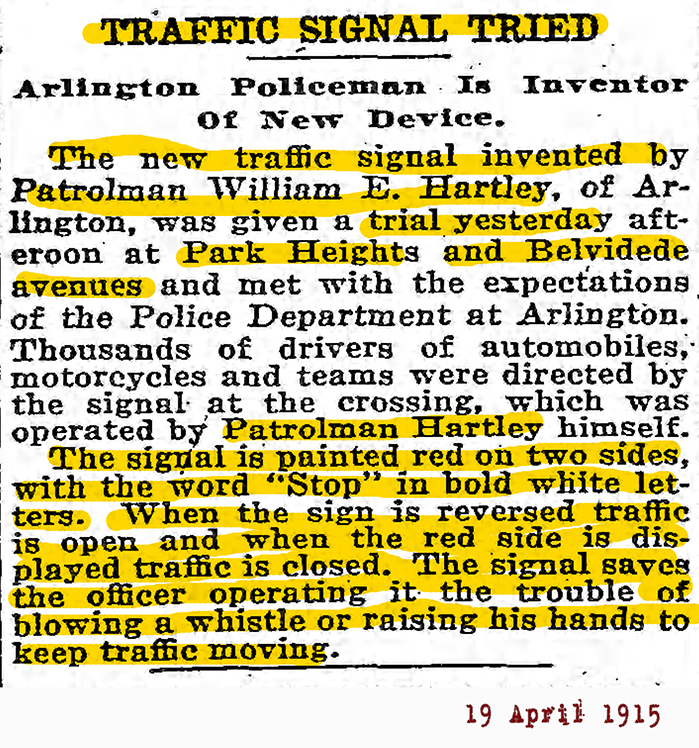

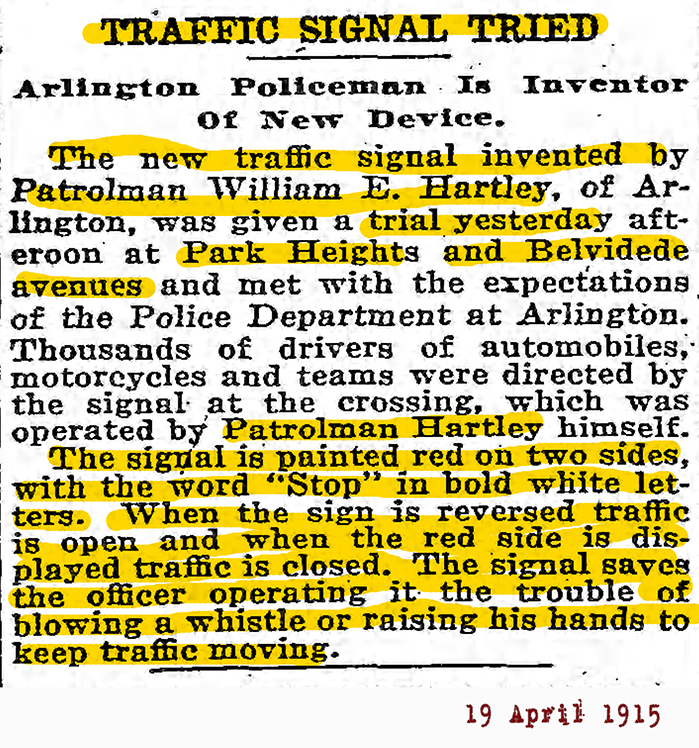

1915 – 18 April 1915 - Patrolman William E. Hartley demonstrated his new traffic signal out at the intersection of Park Heights and Belvedere Avenues where it was met with the expectations of the Police department. The patrolman's device was described as follows. The signal was painted red on two sides, with the word "STOP" in bold white letters. When the sign is reversed, traffic is open and when the red side is displayed traffic is closed. The signal saves the officer operating it the trouble of blowing of a whistle, or raising his hands to keep traffic moving.

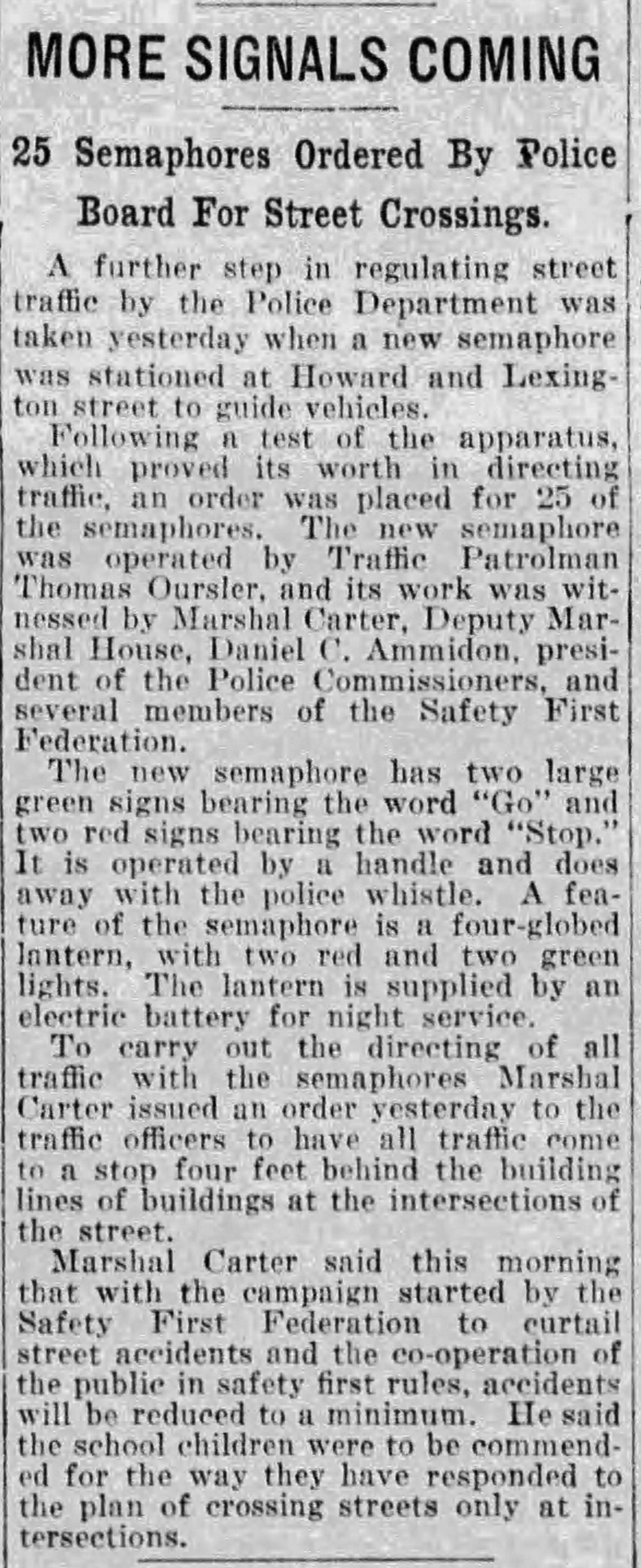

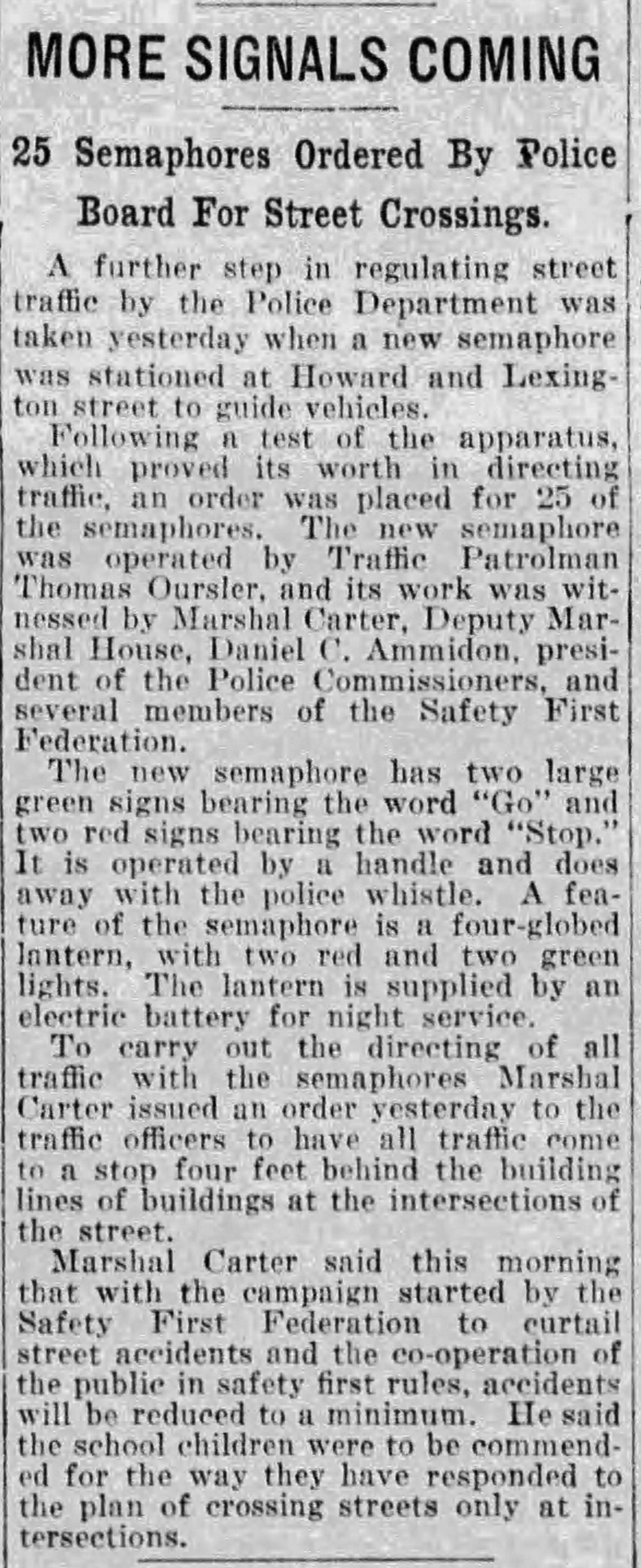

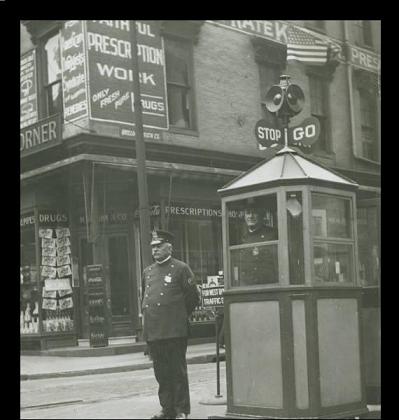

1916 – 26 January 1916 - The Police Board ordered 25 semaphores for street crossing - A further step in regulating street traffic by the police department was taken yesterday [26 Jan 1916] when a new semaphore [Baltimore's first] was stationed at Howard and Lexington Streets to guide vehicles. This system was first used and tested by Patrolman Thomas Oursler of Baltimore's Traffic Division and witnessed by Marshal Carter, Deputy Marshal House, President of Police Board of commissioners Daniel Ammidon, and several members of Baltimore's Safety First Federation. This is the original system which was composed of two large green signs with the words "GO" and two intersecting red signs that read "STOP." It was operated via a pole inside of a pole that was stopped by a small handle, allowing the officer a way of turning that handle to change the indication for intersecting traffic to have in their view either the green "GO" signs or the red "STOP" signs. These were later surrounded by a white metal drum that the patrolman could stand inside of making him more visible to traffic. Eventually, they would include an umbrella to both keep the patrolman dry on rainy days and cool on hot sunny days by providing him with some shade. Sitting on top of this Semaphore was a four-way railroad lantern converted for traffic use with the addition of two red lenses and two green lenses so that in low light dusk and dawn drivers could more easily read the Stop and Go signs and follow the traffic patterns directed by the patrolmen that worked these Semaphores.

Howard and Lexington Streets were the first to be added in that January of 1916 and one of the last removed in late May early June of 1920 by Col. Chas Gaither, who went back to the whistle and point control that we see being used today. The public at the time thought the Semaphores were safer and argued to get them back. For pedestrian safety Traffic Officers were instructed to stop cars four feet behind the building line to allow room for pedestrians to more safely cross the streets.

1920 – 7 June 1920 – not long after Gaither ordered the removal of the Semaphores the Commissioner was forced to go back on his ideas and as such he ordered two of the Semaphores to be returned, those units were located at the intersections of Light and Redwood, and Light and Pratt Streets. Gaither said he had not changed his mind about the Semaphores, but in checking the locations, he felt there was sufficient room between the corners of the intersections for traffic to move through without interference from the Semaphores.

1921 – 6 May 1921 - First Electric Traffic Signal installed in the city at the Mall Crossing in Druid Hill Park. It was installed in place of the old manually operated Go-Go signals, and was first operated by Baltimore Park Police Officer R. W. Wilson on 6 May 1921

1922 – 18 July 1922 – Traffic Officers will be allowed to appear coatless on job while wearing attractive white Oxford Shirts. These officers will start wearing long sleeve white Oxford shirts with a low, turned-down collar and a black tie as they preside to direct traffic on their assigned street corners.

1925 – 6 June 1925 – General Charles Gaither issued an order, effective, 6 June 1925 all members of the Baltimore Police Department who are on duty between 8 A.M. and 4 P.M. may remove their coats provided they are wearing a white Oxford shirt, and a black tie. This privilege has been granted for the previous two years for department’s traffic officers.

1930 – 19 June 1930 – Baltimore Police try a new system for regulating east and westbound traffic on Pratt Street independently; at the intersection of Light Street, was given a trial period to eliminate traffic jams, that were being reported by Inspector George Lurz. Pratt and Light Streets according to statistics compiled by the traffic division showed the location to be among the busiest in the city during daylight hours for vehicular traffic. At the time the control system was confusing by allowing east and westbound traffic to move simultaneously. Westbound traffic was making a left-hand turn onto Light Street interfering with eastbound traffic. So a 3-way Semaphore was being planned to control the traffic better using members of the Traffic Division that would be stationed in the tower at the intersection. The department believed this to be the answer to the problem at what was at the time described as a confusing intersection. The intersection was controlled by a single officer using the old hand controlled Semaphore which was designed with Red-STOP and Green-GO. What made this system a, "3-way system" is where other arrangements have Green-GO, Red-STOP, they added Amber-CAUTION. With its intent is to warn drivers on Green that they are approaching an intersection that is about to change to Red. These 3-way signals were placed on all four sides of the Semaphore Tower. The Red and Green Lights have been helpful, but the addition of the Amber Light has been the answer to a lot of problems throughout the city as it pertains to traffic patterns. This was especially true of confusing or busy intersections. So basically, what they were calling a "Three-Way System," was Baltimore's introduction of the Amber Light to the Red and Green Lights.

1935 – July of 1935 – After learning of a system put into place in Hartford Connecticut, Baltimore's Traffic Division would add radio's to Semaphores at strategic locations throughout our city. With this they could receive up to the minute information on stolen cars [or tag plates] wanted people that could be coming their way. Even more helpful in the possible saving of Baltimore lives was how they arraigned to set things up so that we could share information with Baltimore City's Fire Department. When provided, information on active fires, our Traffic Officers could control traffic patterns thereby clearing intersections, making it easier for fire equipment to more quickly get to the scene of active fires, or medical emergency.

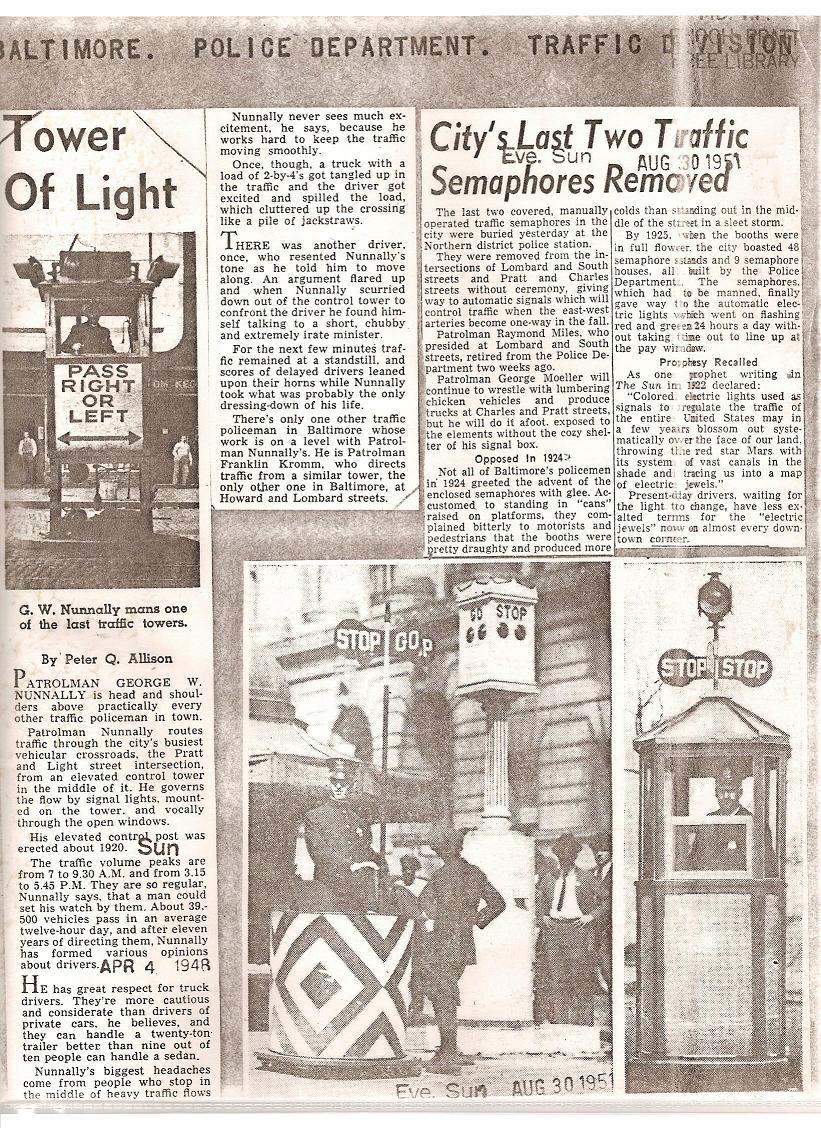

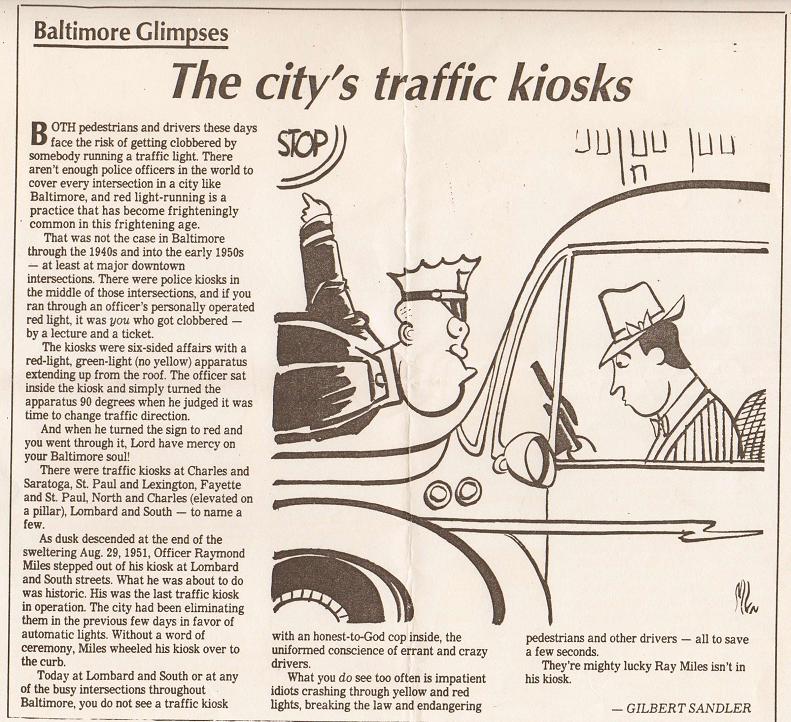

1951 – End of August 1951 – the Enclosed Box/Booth style, and or Tower style Semaphores [seen in the attached 1951 photos] that were initially introduced in 1924 and last used in August of 1951. These Box/Booth style units came in the style that looked like a phone booth, or another version that had the box/booth affixed on top a tower.

1956 – 29 June 1956 – Casual But Official, Patrolman Donald Miller displayed the latest open-neck short-sleeve police shirts that would be worn for the remainder of the [1956] summer by Baltimore's officers. Police officials stressed that only a specific model Oxford shirt has been approved, thereby eliminating the danger of patrolmen selecting the more brightly colored type shirts of their liking.

A Semaphore with a Booth

Gaither ordered two of the Semaphores that had been taken out of service to be returned.

Semaphore Booth with a Green and Red Railroad Lantern affixed to the top of the Semaphore above the Go--Go Stop-Stop Signs called that because to on coming traffic they either saw Go-Go or Stop-Stop atop the sign as they entered the intersection

First Electric Traffic Signal installed in Baltimore City at the Mall Crossing in Druid Hill Park. It was installed in place of the old manually operated Go-Go signals, and was first operated by Baltimore Park Police Officer R. W. Wilson on 6 May 1921

First Electric Traffic Signal installed in Baltimore City at the Mall Crossing in Druid Hill Park. It was installed in place of the old manually operated Go-Go signals, and was first operated by Baltimore Park Police Officer R. W. Wilson on 6 May 1921

.jpg) Traffic Control System

Traffic Control System

1920 Semaphore

1920 Semaphore

This was donated to us by a guy in Middleton, Idaho who appreciates the hard work our police do and where we have come from in history t be where we are today. Looking at the history of our traffic division, you have to admire what these guys have done to fine tune the system we have today, this photo shows, the umbrella we used to keep out police out of the weather, or even just to keep the sun off of them. But what we like best about this pic is the rear-view mirror used to allow our officers the ability to see where traffic is coming from behind him and in front of him, making the direction of these vehicles as safe as possible. Something we don't think about often is what was going on back then when it comes to transportation. this was taken sometime in the late teens early 20s a time when horse-drawn wagons were in use, gasoline engines, some electric cars, streetcars, horses etc. So they had a lot going on, and this man like an orchestra conductor directing a musical performance music, he was directing traffic and if you think of all that could go wrong, especially at a time when traffic lights were not in full use, and in fact, the Semaphore was really just getting started. The add-ons and extras like an umbrella and rear-view mirror show just how far we have come. We thank for the donor for caring about police and our history so much that they would donate an important part of history.

Close-up of the shot above shows a rear-view mirror for the Go-Go Stop-Stop traffic officer. The pic above shoes he also had an umbrella for the sun/rain and stood on a pallet to keep him off the street, he also has a drain not far off to the side of him so the pallet may have had a second purpose

Traffic booth and Officers directing traffic at Liberty and Lexington Streets

Traffic booth and Officers directing traffic at Liberty and Lexington Streets

Traffic Lights, Intersections, Vehicles and Pedestrians Lead to Crosswalks

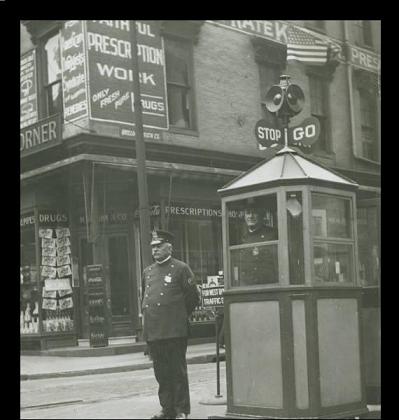

We would have a difficult time introducing the traffic light if we couldn't introduce the crosswalk. Baltimore started using our crosswalk system in 1914, intersections on Baltimore Street from the Fallsway to Howard Street, and on Howard from Baltimore Street to Franklin, would receive these thick white line telling pedestrian where they needed to be when crossing the streets in this part of town. The concept seen in Cleveland and Detroit could be seen first on these downtown streets, but before long they would be on nearly every major intersection in the city. The Goal was to save lives, as more and more cars came into the city and these cars were being made to go faster and faster, those on foot needed to earn to interact with these machines in a uniform, and safe manor.

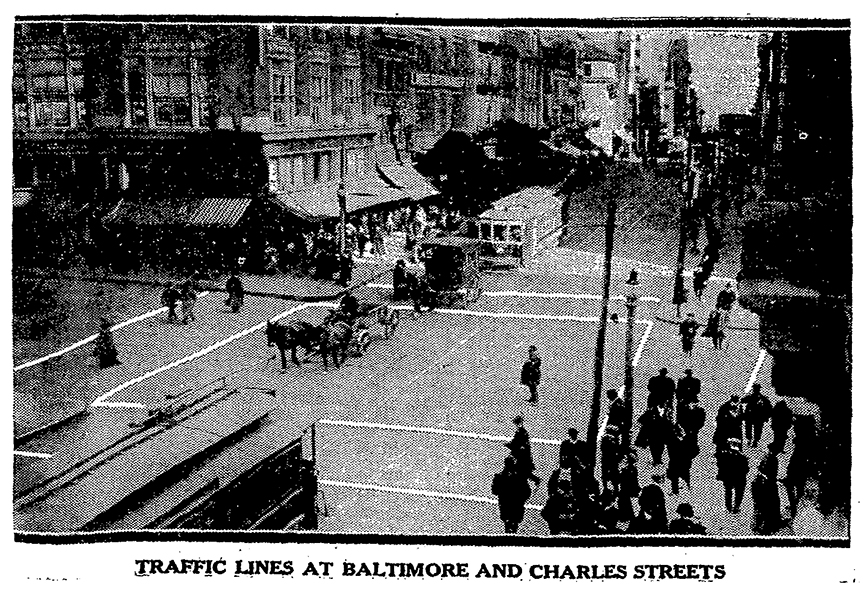

Baltimore St and Charles St

1914

15 November 1914

WALK THE STRAIGHT AND NARROW PATH

VINCENT FITZPATRICK The Sun (1837-1989); SN1

Walk the Straight and Narrow Path

What are those white lines painted on the street, stretching right across the asphalt, mean? Scores asked the men who were painting, hundreds have looked at them, stopped and wondered.

Thousands who walk through the business district of the city have noticed recently at the street intersections of Baltimore Street from the Fallsway to Howard Street, and on Howard from Baltimore Street to Franklin, these heavy white lines on all four sides of the intersecting streets. The lines extend from curb to curb, those on the north and south sides of the street running East and West, and those on the east and west sides of the streets running north and south.

One of the lines on each side runs coincident with the building line; the other with the curb between these lines all Baltimoreans who use Shanks’ mare as their mode of traveling must walk in the future. There is to be no “cutting catty-corner” at these intersections. Everyone must hew to the line or the policemen stationed at these crossings will know the reason why.

In Cleveland and Detroit.

In other words, Baltimore is about to inaugurate an arrangement in the way of handling the traffic situation that has been in vogue for some time in the number of large cities of the country.

Those who have visited Cleveland and Detroit have undergone the experience of being held up by the policeman at the crossing when they attempt to scoot diagonally from one corner of the street to another. They had to go around about way, and perhaps some of them have murmured at what they thought of as a useless and childish procedure. In some of these cities, the lines are not used, while in others there is quite an involved system of lines. Which it takes a little time to puzzle out. In all of these cities the adoption of either the line system or that used, for example, in Cleveland, where the police simply directed the way the Pedestrian shall go, has been rewarded with beneficial results in the saving of life and limb.

In Baltimore, in the last five years, the toll of life and limb exacted by streetcars, automobiles and other vehicles has been considerable. Perhaps 50 persons have been killed or died from their injuries. It is doubtful if, in all this list, there can be found a verdict given by a coroner’s jury in which the victim of the accident was not blamed to some extent for carelessness. In every instance, it seems to have been a case where the person who was killed steps to directly in the path of the automobile or the trolley car, and that the motorman or the chauffeur had no time to bring his car or automobile to a stop.

Often there have been no disinterested witnesses to the accident. The victim’s lips are sealed by death. The person who ran him down naturally testifies in his own defense. With conditions existing as they are in Baltimore today, it is a wonder that more persons are not killed or injured. There are always some few persons so careless and driving automobiles and other vehicles that they are a constant danger to pedestrians. As long as some men will not respect the rights of others and as long as many people are so careless of their own protection, the city must step to the defense of those who either cannot or will not take care of themselves.

The Way It Works

The layout of these lines is regarded as an important step toward the better handling of traffic. City engineer McKay is initiating the innovation. He will shortly write a letter to the board of police commissioners asking them to have the members of the Police Department cooperate with city authorities in seeing that the new plan is carried out.

When that system is put in force a person wishing to cross, say from the south-west side of Baltimore and Charles streets to the northeast corner of Baltimore and Charles streets, will have to walk east on the south side of Baltimore Street to the southeast corner of the intersecting streets and thence North to his objective point. There may be some persons who object on the grounds that this means a waste of time and energy. Doubtless, they will in the future see its good points.

When once the traffic patrolman gives the signal for persons moving east and west to move on every vehicle bound North and South must stop. When he gives the sign to those on their way north and south every vehicle moving east and west must stop every person moving along between the lines is absolutely protected. If, though some disobedience of the law of a driver should persist on his way and a person is cut down between the lines, the party guilty of the violation will have practically no defense and will probably have to face a lawsuit for damages.

The city engineering department intends to place these lines throughout most of the traffic-congested districts. It is the only continuation of the policy of the city officials that “life is not cheap.”

The Useful Traffic Squad

It will surprise some to learn that the money required for the protection of people from injury resulted from the traffic reaches into the thousands and the thousands of dollars more will be expended. Even at that, the safeguards for the pedestrians will not be enough, and those who of studied the question believe that the time is coming when a special yearly appropriation will be made for this purpose.

Until a decade or so ago this city had practically no traffic squad. Indeed when the idea was first breached the proposal met with more or less derision, and those who were appointed to this special work were referred to as members of “the beauty squad.” Baltimoreans have ceased to laugh at that squad. They know the work its members have done in saving aged men and women and children from death in those streets were “big business” and unmindful pleasure hustled and bustle along apparently careless of the rights of others. There are in the city today 39 members of the traffic squad, including three mounted policemen. Of sergeants Barry, and Zimmerman, with deputy Marshal house as the directing head. These men are stationed at all of the principal traffic corners downtown or at what some call the “automobile death traps”. These “traps” are at North and Charles streets, St. Paul and Chase streets and St. Paul Street and Mount Royal Avenue.

These patrolmen work from 7 o’clock in the morning until 7 o’clock at night. One half of the squad works on Saturday night from seven to 11 o’clock. The officers are not kept on duty on Sundays, except the one man who was stationed at Charles Street and North Avenue. This assignment is taken in turn, which means that each member of the squad has to work approximately one Sunday in every 39.

Many Warning Signs

More policeman for this work is needed and needed badly, officials say, but as there is no money appropriated the next best step is taken. Signs have been printed warning automobiles and others what they must do in order to conform to the traffic laws. Signs are fixed at dangerous places where it is impossible, because of lack of numbers, to station a patrolman. The signs cost eight dollars apiece, but they last many years. The patrolman must be paid $20 a week. Therefore, the signs are much more economical, though perhaps not so powerful in the way of restraint as the policeman.

To further the “safety first” Crusade, the officials of the United railways have placed posters in the trolley cars requesting passengers not only to be careful while getting on or off the cars but also warning them of the need of being watchful while crossing or walking in the street.

The automobile club of Marilyn now keeps on the streets and automobile caring large signs on its side warning pedestrians of the necessity of watching out for automobiles and other vehicles. This is sent out the only through the city, the automobile thus constituting a running lesson of advice.

Moving – Picture Lessons

Deputy Marshal House, who is intensely interested in the “safety first” movement, is greatly pleased with the results that have followed one method of campaigning in this matter. There are 200 moving picture houses in Baltimore. In these houses at least once a week warnings tell of the dangers that are to be met within the city from moving vehicles. They urge the readers to “stop, look and listen” before attempting to cross a street. They tell children of the dangers of stealing rides on the back of wagons, cars, etc. And these lessons produce an impression.

The police are always on the lookout to detect those who violate the traffic laws. In stables all over town, the traffic rules are posted. Thousands of little pamphlets, published at the city’s expense, containing the traffic rules and the penalties for violating them have been issued to chauffeurs, automobile owners, and drivers.

In the case of minor violations of the law by drivers of wagons, the rule that is generally followed is to take the name of the driver, if it is his first defense and the name of his employer. The employer is then notified that his employee as disregarded the law and he is asked to advise his men not to repeat the offense. If the offense is committed again the violators arrested and fined.

To “Park” Vehicles

Deputy Marshal House is striving to get the owners of the various business houses and big office buildings interested in a new plan of his. He wants them to purchase signs, to be used in front of their buildings, telling automobile list and drivers to “park” their vehicles within certain lines to be marked off in front of the buildings. This is to keep the entrances to the buildings clear.

There is one good thing that the deputy marshal believes will result from such a plan, and that is the expediting of the collection of the males. Because of the congestion in front of mailboxes, the post office employees have often been delayed a minute or more a box in the taking up of such mail. This means lost time and inconvenience to the businessmen and others in getting their mail.

The popularity of roller-skating brought about by the increase of smooth payments has given a new problem for the police to solve. Regulations had to be made and enforced, giving the children the right to use certain streets at certain hours for their fun. Some of the too – fond skaters had to be protected against automobiles and vice versa automobile us had to be protected against heedless skaters.

May Restore the Whistles

In the downtown section the traffic police for a long time he used the whistle system in the directing of traffic. One blow of the whistle meant the movement of traffic North and South; two blasts met the movement of traffic East and West. This system was discontinued, traffic being direct it now by the waiving of the hand. Part of the present system, according to Deputy Marshal House, has proved unsatisfactory and he has brought before the board of police commissioners a proposal to bring back the whistles again. It is said that many drivers, especially Negroes, who sometimes drive along half asleep, fail to notice the wave of the officer’s hand, and much confusion has resulted. The sharp whistle keeps a man awake and alert and wakes up the sleeping or the stupid.

There are f new traffic problems arising every day as the city grows. It is a big thing, the protection of the people – a job well worth what it costs. Over in Northeast Baltimore and down in the crowded sections of East Baltimore, hundreds of people have been injured more or less seriously, and some have lost their lives because the streets were not better guarded. Especially is where need for the protection of children and elderly persons, and down there, where they have never had any officers to look after pedestrians and hold teams and motorcars in check, traffic police are needed.

It’s a big problem, one that Baltimore has handled pretty well, with its limited force, in the past few years, but it’s planning to manage by a better and more comprehensive system in the future.

Downtown Traffic Policeman Howard and Lexington 1920 In This Pic, We See The Semaphore Booth with a Green and Red Railroad Lantern Affixed to The Top Just Under the Signs and Lanterns, We Can See The Officer's Umbrella, In This Case, Keeping Him Out of The Hot Sun

Nice Committee Calls Three Traffic Experts

Three traffic experts will appear before Governor Nice's automobile insurance committee at a meeting to be held at 8 P. M. Tuesday at the Emerson Hotel. They are:

Dr. S. S. Stineberg, Dean of the College of Engineering of the University of Maryland, who is conducting the traffic school there. John P. Rostmeyer, director of the Baltimore Safety Council. Preston D. Callum, chairman of the Baltimore Traffic Committee. The committee was named by the Governor shortly after the first of the Year to make a study of Automobile Insurance in the State and to make Recommendations to him and the next General Assembly.

Members of the committee are:

George W. Baulk, a chairman, and W. Harry Haller, of Frederick, representing

The insurance companies. John T. Shipway, of Flintstone; Jos. Eph S. Bigelow, of Annapolis, and J. Francis Rahlke, of Westminster, representing businessmen. Max Sokol, secretary, and Robert R. Carmen, representing the legal profession. The last Legislature passed a resolution calling for the appointment of the committee.

Baltimore's New Traffic Engineer

KEITH WYATT

The Sun (1837-1987); Jun 20, 1937; pg. 78

Baltimore’s New Traffic Engineer

Tomorrow Wallace L. Brown Starts Simplifying the Street Tangle

By Keith Wyatt

Tomorrow morning a new member of the Baltimore Police Department will walk into the police administration building and hang up his hat just long enough to orient himself and map his future course with his superiors and collaborators. Then, armed with the Lance of special training, he will go out to tilt with a formidable foe – Baltimore’s tangle traffic.

Nine months of intensive study with the nation’s best-known traffic experts have given Wallace L Perry of Braun, a former member of the engineering staff of the city’s Bureau of mechanical electrical service, with a degree of the traffic engineer. Sent to Harvard Bureau for street traffic’s research by the sun papers last fall, he has received instruction for men recognized as leaders in his young profession, which is filling a big gap between the civil engineering which builds streets and the police authority that enforces traffic laws on them.

Recently Mr. Braun came home for a few days holiday – a businessman’s holiday, during which most of his time was spent in cruising about the city, sizing up some of the problems he will be called upon to solve and planning some of the recommendations he will make to his superiors out of his store of knowledge.

He entertains no belief that Baltimore’s traffic snarls can be unraveled without some radical changes in the rules governing Streets parking and traffic at certain notoriously bad intersections, in true routes, in stop-go light controls and an accident investigation, and is naturally encouraged by the City Council’s recent steps towards cooperation with the police department.

But eager as he is to try his wings, the traffic engineer – to – appear to be imbued with a sense of caution that may stand him in good stead. Soberly he looks ahead at his new job and as to specific details Admits: “I don’t know just how I shall operate. So much depends on the full cooperation not only the entire police department but other city departments and civic organizations as well. It will take some months to develop a working plan whereby the city can begin to show a profit on the talents that have been given me.”

Nevertheless, Mr. Braun is not wholly lacking in the program. Subject to the approval of his superiors, his first efforts will be toward the organization and the establishment of a liaison between all groups primarily interested in the safe and expeditious movement of traffic. Beyond that, he hopes to apply much of his knowledge to the many conditions that govern traffic behavior. Already holding a degree in electrical engineering (bachelor of engineering, Johns Hopkins, 1926), he has added a full understanding of traffic signals and other control mechanisms. Grounded, too, in civil engineering, he now has gained a wider knowledge of the effects of Street plan, condition and arrangement on traffic movement. In addition to these things, he has assimilated a store of miscellaneous information, mostly hard bought by other cities that have made credible records in their attacks on the traffic problem.

“I would like to dispel any notion that I am coming in here to “run” traffic,” the engineer said, “I have just hired the help of a special sort. The traffic division knows more than I will ever know about the enforcement of traffic laws; the public works department was building streets before I was born. But I have learned a lot about those things that influence the rapid and safe movement of traffic, and I believe I have a lot that both of these departments can use.”

One of Mr. Braun’s earliest endeavors will be to organize an adversary committee composed of both official and civic representatives. He reports that cities that have made some of the best records in traffic have had such boards to advise with the traffic engineer. As he visualizes it, the committee would be made up of a high emissaries of the police, public works and educational departments, ex officio, and of representatives of the Safety Council, automobile clubs, mass transportation systems, taxi and trucking interests, retail merchants Association, and Baltimore Association of Commerce, Commission on city planning, the city solicitor’s office and the real estate board.

“Such a committee would represent the views and experience of every classification of traffic,” the engineer said, “form of four I have watched the progress of the mayor's traffic committee in drafting a program of segregation of rail and freewheel movement.

The committee, headed by Preston D. Callum, of the Safety Council, has served to show what can be accomplished when a big, interested group seeks, and fines, a common line on which to proceed toward worthwhile ends.

“I hear with regret that the Callum committee has asked that it be disbanded. I would like to work with that group, but if it does break up I sure hope that another may be formed on the same sound lines”

A special interest to Mr. Braun is the committee’s study of the “hundred worst intersections” in the city, made some time ago with relief labor. While no specific recommendations were made for correction of dangers at these intersections, the data, Mr. Brown believes, will form the basis for some remedial action, if cross-section studies can be made to bring them up to date.

The engineer hopes that he may embark at once on a broad survey of the city’s traffic and the problems associated with it. From this reconnaissance he believes he can set his own course, looking for sound recommendations for improvement. It is necessary, too, he says, to determine what can be done within the resources of the department, reported being scanty in comparison with cities of similar size.

Mr. Braun is cautious on the timing of traffic signals and their lack of coordination that causes many snarls during busy hours in the city. He points out that the “mixed traffic” of streetcars and freewheel vehicles on every street in the business section makes coordination practically impossible in some places – a condition that will be rectified to some extent as the Streetcar real routing plan of the mayor's traffic committee goes forward.

Under this plan, most of the rail movement will be confined to certain “streetcar streets,” leaving other arteries entirely to freewheel vehicles.

Asked what he would do with so-called “wave systems” one St. Paul Cathedral streets, Mr. Braun said he has had no opportunity to familiarize himself with the mechanism and, therefore, cannot now judge to what further extent it may be adapted to the changing needs of traffic.

“In many cities, the timers are changes so that longer portions of the cycle are devoted to the heaviest traffic at Rush speak,” he explained, “I am in no position yet to say what can be done here. The police have had a difficult problem, and to meet it good equipment is needed. I do not know, of course, was of the city has such equipment.”

What did Mr. Braun sink of new bypasses for through traffic? He shook his head. “I can’t discuss that with you,” he said. “Adequate bypasses to relieve the busier sections of a load of transient traffic are important to any city. I was much interested in reading of the studies of the mayor's committee which, while it has advanced no specific recommendations, at least outlined several possible routes that might be developed, New York, Philadelphia, Chicago and province all have exceptionally fine bypasses that are well worth study. Perhaps such routes can be found here; I don’t know.” Well, what about limited ways – those express routes with no cross traffic? The engineer shrugged his shoulders. “Best way in the world to cut congestion and move traffic rapidly out of the business section, but they are expensive,” he declared. “Some cities say they cannot afford them; others that they cannot, in the light of their traffic problem, afford to be without them. For my present distance, I do not see any signs of an aroused public opinion that would bring them to Baltimore. As a matter of fact, I have had no opportunity to even find out whether the city needs them yet, or whether other expedients might do for the time.”

Parking, then? And Mr. Braun any ideas on how to solve this pressing problem of Baltimore’s narrow streets? Again he was wary. “I have no right to talk about that,” he explained. “No city has “solved” is parking problems yet. Speaking generally, traffic engineers look to the day when street parking of automobiles can be abolished; when all Street space can be used for its original purpose – to move traffic. They are convinced that it is poor economy to use expensive paved surfaces for dead storage when other space can be found and that is cheaper, allowing cities, in effect, to broaden their streets by two full lanes. Someday we may come to it, but just now I cannot speak with any authority on Baltimore’s parking problem.”

Mr. Braun conceives the first need of any traffic engineer to be a “good set of traffic eyes” – that is, an efficient set of records. Particularly does he deem accident reporting a necessity in any intelligent approach to street and highway safety?

“If you know where accidents are happening, you can find out what to do about them,” he remarked. “Whether it be an enforcement job, a matter of lighting, the need for signals or signs to be removed or physical hazards, they also up in records properly capped.”

He believes, also, as do most other engineers of his calling, that every city and state should have a special investigation of traffic accidents, just as they have special investigations of other violations of the public safety. He is convinced of that accident investigation squads take the guesswork out of safety efforts, bring law violators to justice and gardeners and people from injustices often sustained to half hazards dealing with accident cases. The moral of fact on the public is good, he thinks, and, besides, such procedures improve records so greatly that the whole problem may be attacked more intelligently.

Before the Baltimore engineer’s eyes are ever the “Three E’s” of traffic movement, control, and safety – Education, Engineering and Enforcement – set up by the traffic engineering fraternity as its guideline. Each is a separate and distinct function, he says, but all three must be correlated to assure a proper approach to safe, sane and rapid traffic.

Mr. Braun was born in Hyattsville 33 years ago and came to Baltimore with his family when he was six. He was educated in the Baltimore public schools, the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute at Johns Hopkins University. After his graduation at Johns Hopkins in 1926 he joined the technical staff of the Consolidated Gas, Electric Light, and Power Company, being assigned to steam stations. In 1929 he resigned to take a position in a Bureau of mechanical electrical service of the city department of public works. He served an adversary and executive capacity on electrical and combustion engine projects of the city until shortly before he was sent to Harvard Bureau.

Last summer, recognizing the need of the city for a highly specialized engineer to handle traffic problems the Sun paper offered to provide a man of police Commissioner Gaither’s choice with a year’s scholarship to the Harvard Bureau for street traffic research. Commissioner Gaither, believed that, because of high educational requirements in the Harvard graduate school, the candidate should be selected from the engineering, rather than the police, staff of the city, conferred with Mayor Jackson and the chief engineer Bernard L. Crozier as the man best suited by former training to undertake the work, the Commissioner Gaither prepared to make room for him in his own department when he should have qualified as a traffic engineer.

With the expiration of general Gaither’s third term of office two weeks ago Commissioner William P. Lawson succeeded. One of his first pledges was of special attention to the city’s traffic needs, which he recognized as large and numerous and urgent. After discussing the project with inspector Atkinson, head of the traffic force, he expressed a lively interest in the coming of Mr. Braun, and confidence that the combination of theory and practice within the Police Department would lead to the great betterment of the city’s traffic conditions in the near future.

Mr. Braun’s final dissertation at Harvard, completed just before the finishing of his euro special training, it is interesting to note, was on “organization of municipal traffic engineering offices.” During the course of his studies, he was given, in addition to a wealth of theoretical training, actual engineering work in the field. He observed, during his studies, traffic engineering technique of cities with best records of traffic deficiency; he with his fellow students, made actual traffic studies in and around Cambridge and Boston, and he accompanied accident investigation squads in the unraveling of cases, aiding in his work himself.

He has studied the traffic engineering methods of Washington, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Milwaukee and Buffalo at first hand. He feels now that his training, under Dr. Miller McClintock, probably the best-known of America’s traffic engineers, and other specialists of the fraternity, has fitted him to undertake his duties here in Baltimore.

Foot Traffic Division, in front of the Headquarters building

October 24, 1940

Urges Standard Traffic Signals

27 November 1927

Police Commissioner Suggests a System for use in All Cities

Would aid walkers

Gaither favors yellow

At crossings for those on foot

Adoption of a standardized system for automatic traffic control was suggested yesterday by Charles D Gaither, Police Commissioner, in discussing the variation of timing and manner of operation of signals and other cities of the country to regulate the movement of traffic.

“If this plan were adopted, the motorist would soon catch on to the scheme and would get the fullest advantage of driving by the signal,” he said. “They would become so well acquainted with it that when they drove into another city, they would not hold up traffic, as they tend to do now when forced to stop to puzzle over the meaning of the lights.”

Suggest national movement

To bring about the standardization plan, Mr. gator suggests that automobile or traffic associations be formed in all cities and that the groups be represented at a national meeting. New ideas about traffic lights could be exchanged at such meetings, and remedies for defects and signal systems in different cities could be suggested, he pointed out.

“Not that one specified plan should be carried out in every minute detail, but the general principle of a certain plan,” Mr. Gaither explained. “By this, I mean the color of the lights, the timing and the construction of the signals and the way in which it is mounted.”

Disapproves New York plan

Mr. Geiser said he did not believe; there was a city in the United States that was satisfied with the way it signals were operating.

The two light signal in use in New York is not approved by Mr. Gaither. He said he had found that motorists and pedestrians become confused where there is no interval light in the signal.

The New York signals have only the red and green lights, with a five-second interval for traffic to clear up between flashes

Mr. Gaither expressed the hope that a yellow light meaning “go” for pedestrians would be established in Baltimore. He said that as far as he could see, that would be the only possible way to make the crossing at intersections safe for pedestrians.

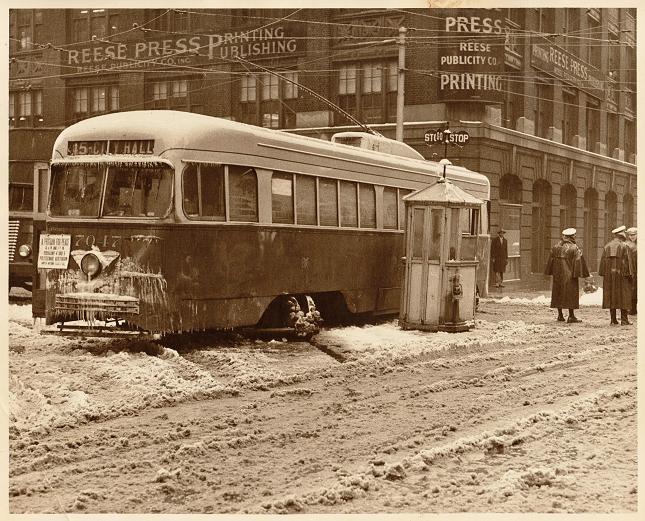

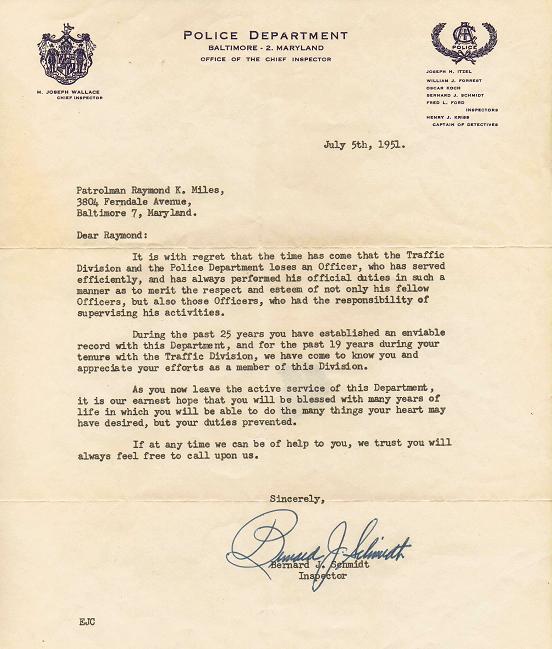

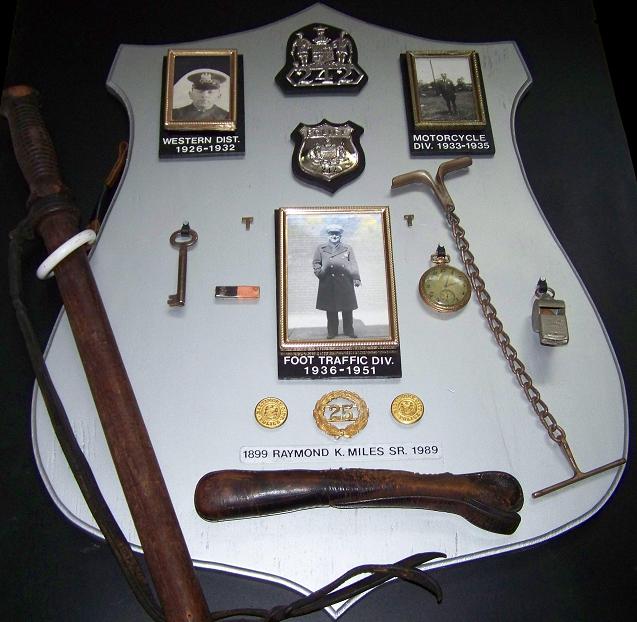

Photo courtesy Raymond K. Miles Jr.

Kiosk located at South St. and Lombard St. where the old News American Co. was located.

The traffic control device was decommissioned in 1951 when Patrolman Raymond Miles retired.

Photo courtesy Raymond K. Miles Jr.

Patrolman Raymond K. Miles worked in the Traffic Unit for 16 years

Photo courtesy Raymond K. Miles Jr.

Kiosk located at South St. and Lombard St. where the old News American Co. was located. Note the old Baltimore Streetcar which was headed to City Hall in a snowstorm. This Kiosk was worked for many years by Patrolman Raymond K. Miles.

SEMAPHORES

sem·a·phore [sémm? fàwr] n 1. system of signaling: a system for sending messages using hand-held flags that are moved to represent letters of the alphabet 2. mechanical signaling device: a signaling device for sending information over distances using mechanically operated arms or flags mounted on a post, especially on a railroad Encarta ® World English Dictionary © & (P) 1998-2004 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

Photo courtesy Raymond K. Miles Jr.

Officer Raymond K. Miles, Sr. worked his post directing traffic from the Kiosk at South and Lombard Sts. The hot muggy Baltimore dog days of summer trying to keep cool proved to be a problem. Patrolman Miles soon learned a way to keep cool. He discovered that taking the leaf from a head of cabbage that had been soaked in ice water, placing it on top of his head and covering it with his hat., Patrolman Miles remained "Kool as a cabbage". This is only one of the many things that Baltimore Policemen soon learned to make their working conditions more bearable.

Memorial plaque to Officer Raymond K. Miles, Sr. showing all of his original police equipment, which is kept by his son, Raymond Miles, Jr. as a reminder of his dad's service to the City Of Baltimore and The Baltimore Police Department.

1928 - February 22, 1928, The first vehicle actuated control was tried out in Baltimore. (To the best of our knowledge this was the first vehicle actuated signal insulation in the world.) - This was an automatic control were a brake attachment and two funnels placed on poles on the right-hand side of the cross street, ordinary telephone transmitters being installed inside the funnels. These transmitters being connected to the sound relay, which when disturbed by noise, for example, the tooting of horns, blowing of whistles, or the sound of voices would actuate the sound relay, releasing the break on the automatic control permitting the motor to run. This would change the signal which had been green on the main street to amber, then to read, permitting the side street traffic to move out on the green. It would automatically reset to red. This device was invented here in Baltimore. - This control would always restore itself back to the main street green, then the break would set and the signal would remain green on the main street until disturbed again by sound. Several of this type were installed, one being at Charles Street and Cold Spring Lane, another at Charles and Belvedere Avenue

POLICE INFORMATION

Copies of: Your Baltimore Police Department Class Photo, Pictures of our Officers, Vehicles, Equipment, Newspaper Articles relating to our department and or officers, Old Departmental Newsletters, Lookouts, Wanted Posters, and or Brochures. Information on Deceased Officers and anything that may help Preserve the History and Proud Traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

If you come into possession of Police items from an Estate or Death of a Police Officer Family Member and do not know how to properly dispose of these items please contact: Retired Detective Ken Driscoll - Please dispose of POLICE Items: Badges, Guns, Uniforms, Documents, PROPERLY so they won’t be used IMPROPERLY.

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll

Save

Save

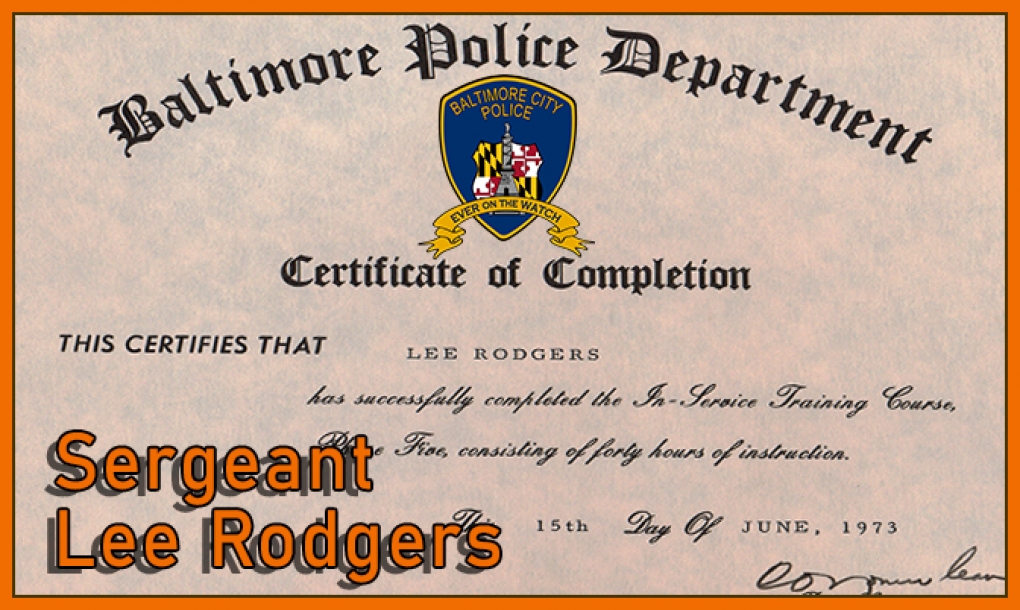

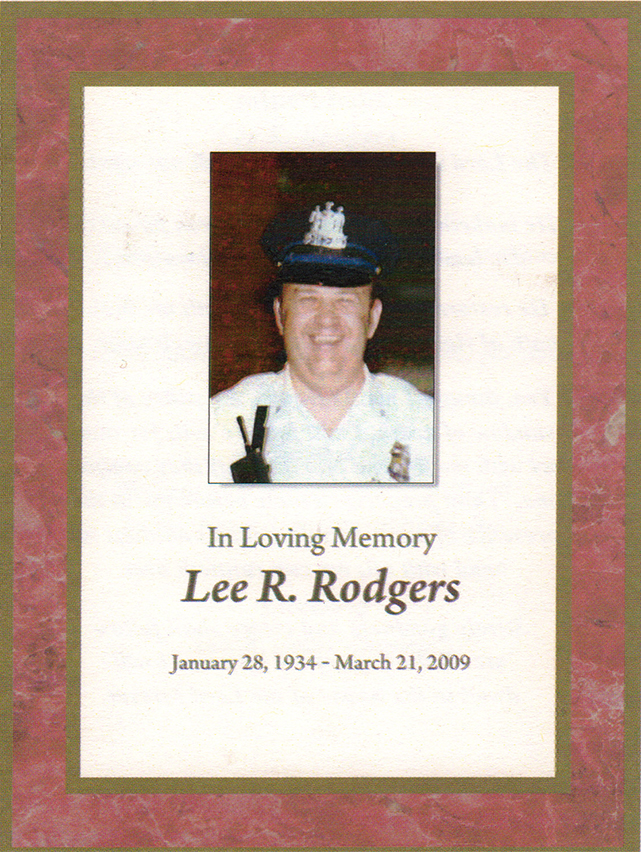

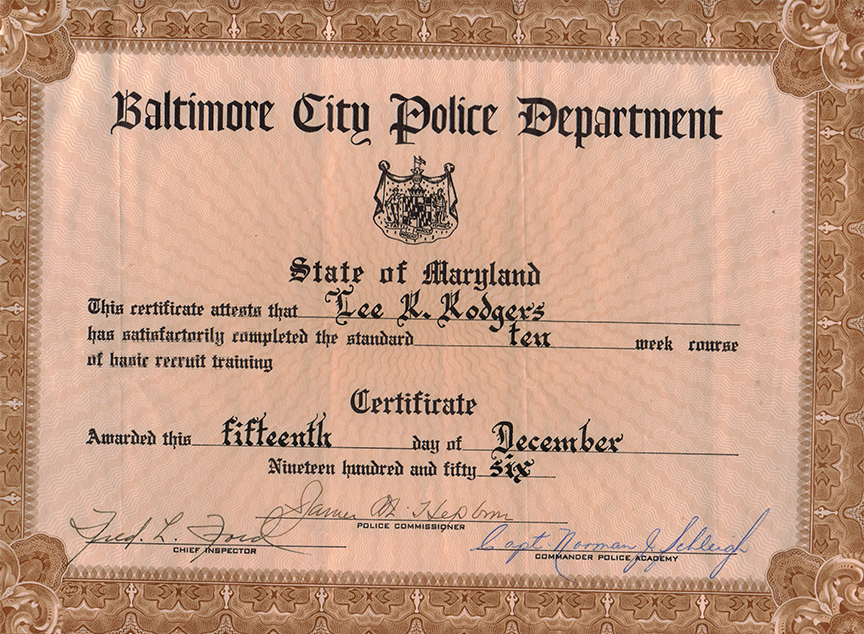

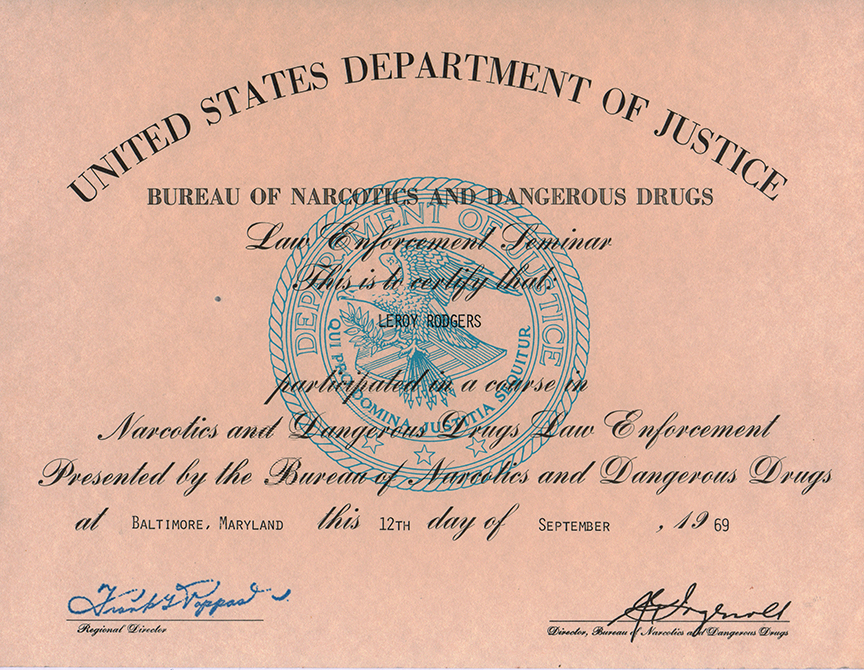

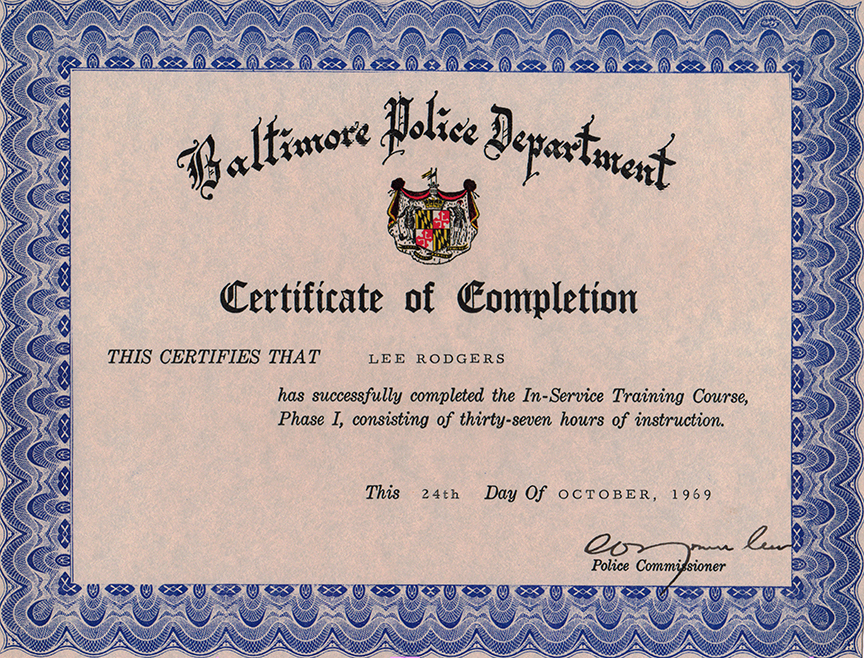

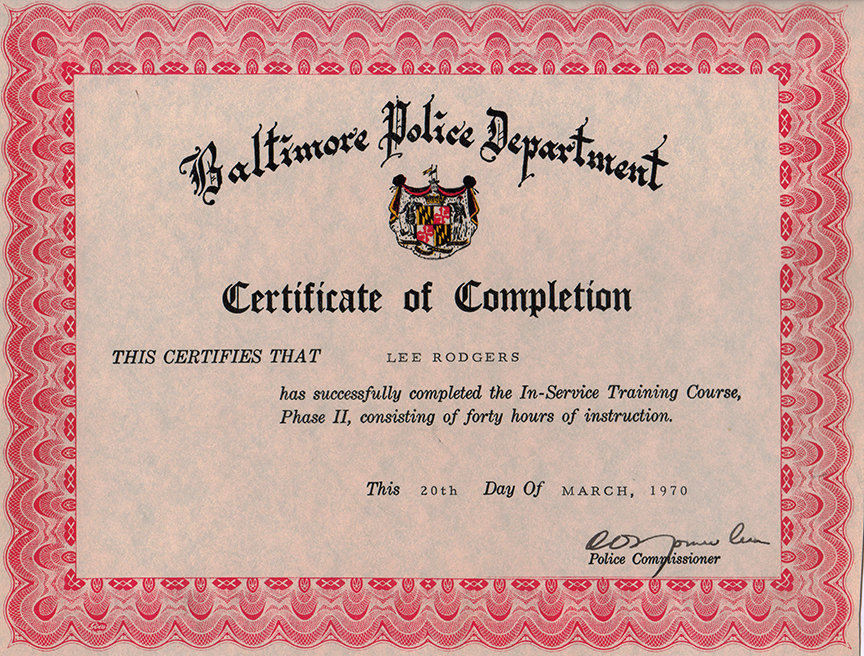

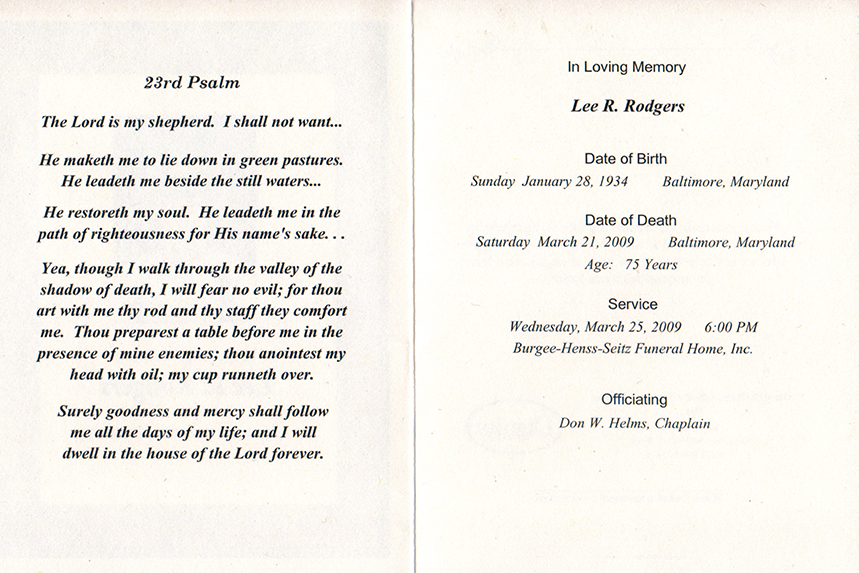

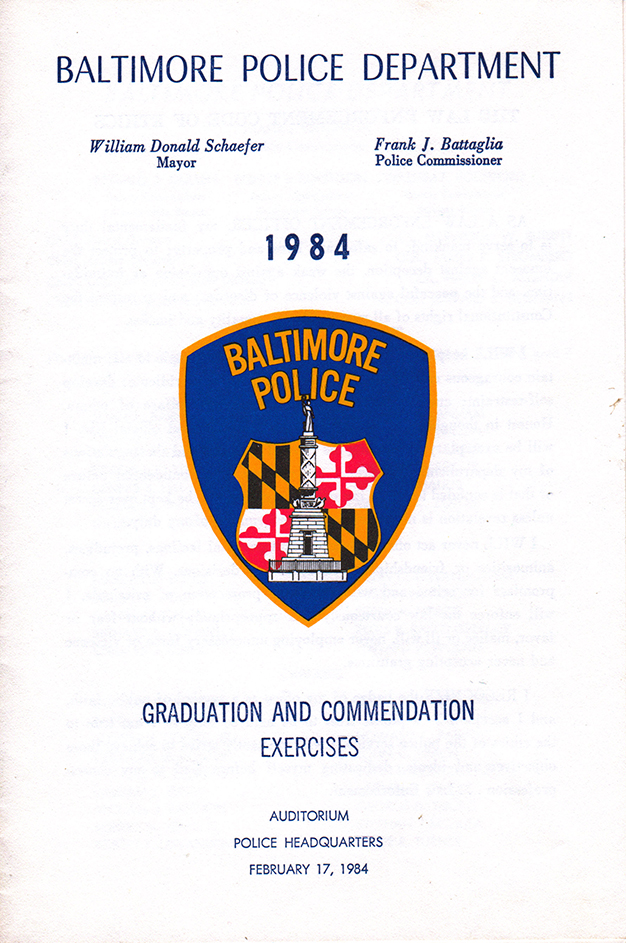

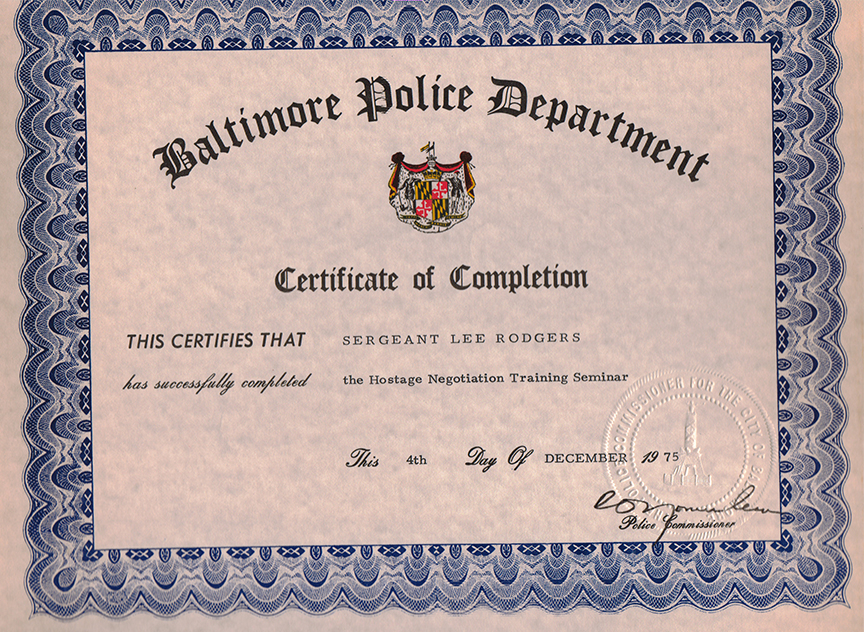

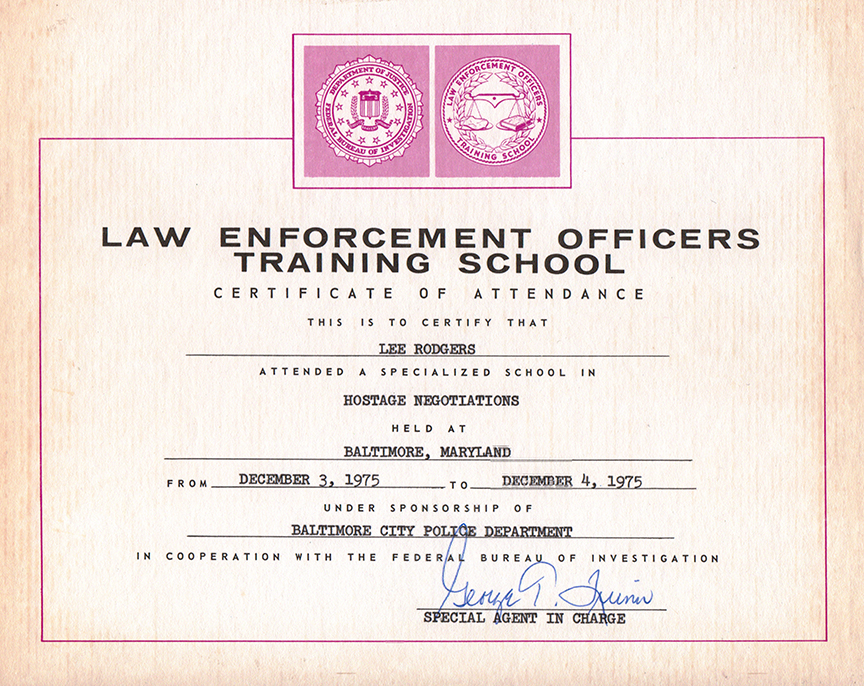

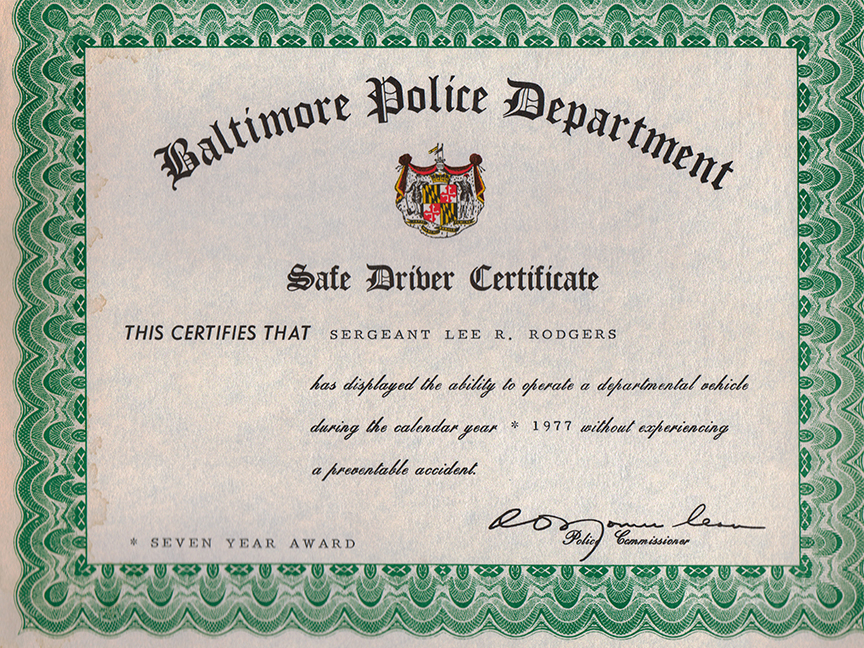

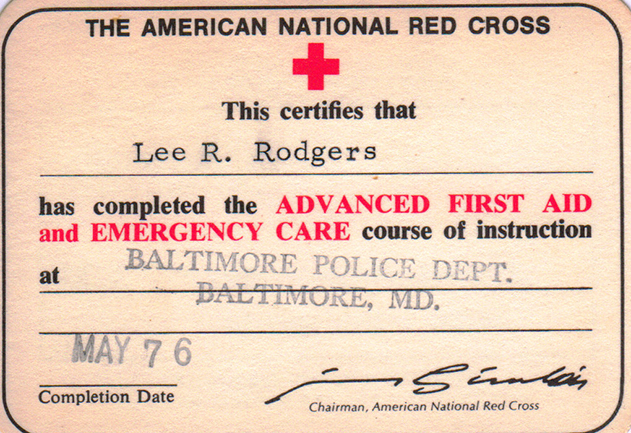

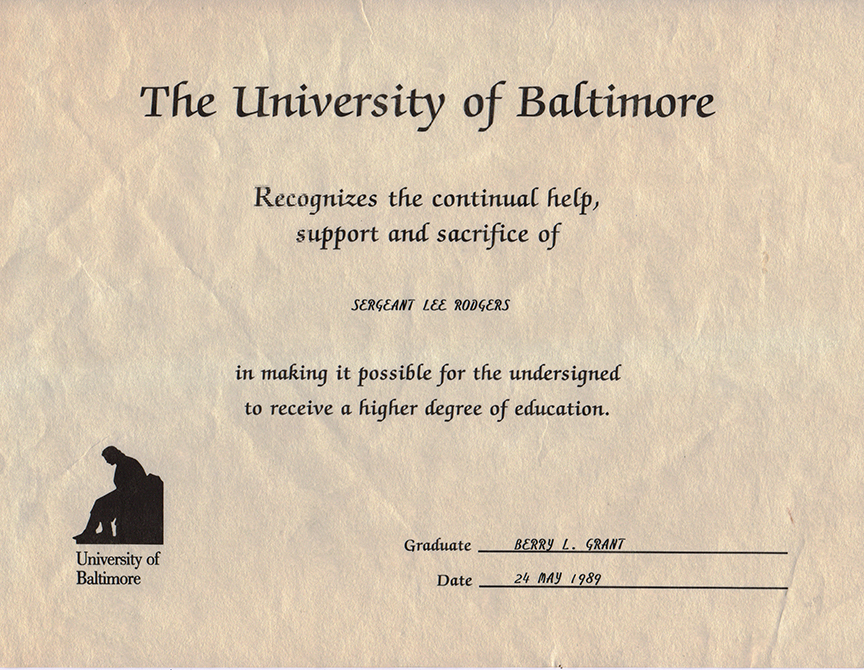

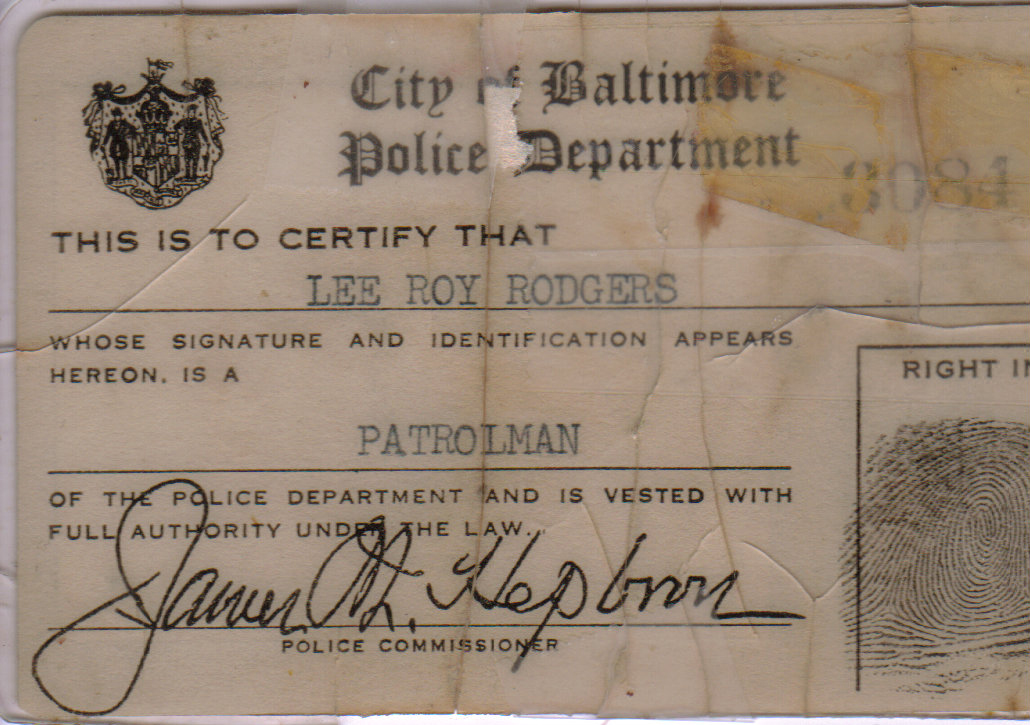

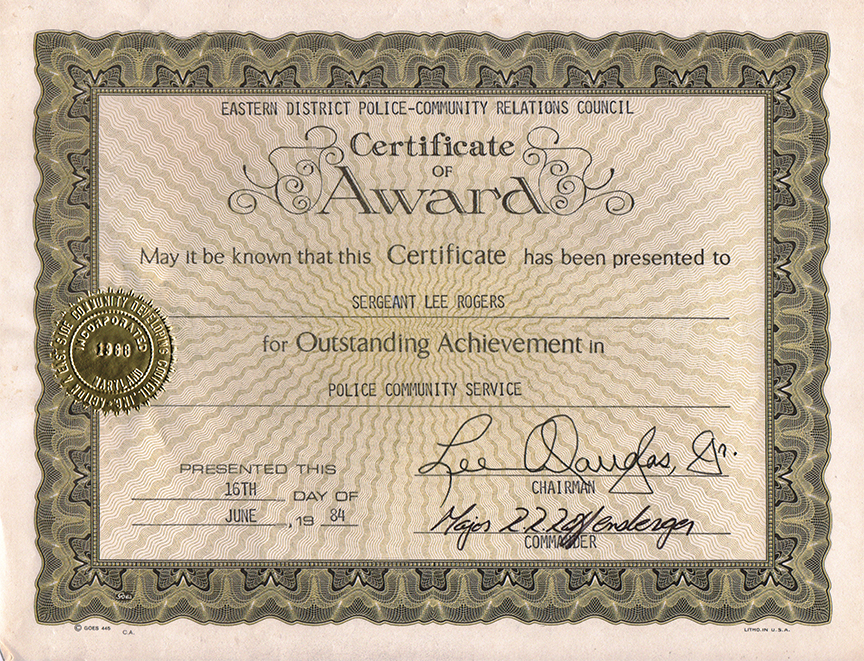

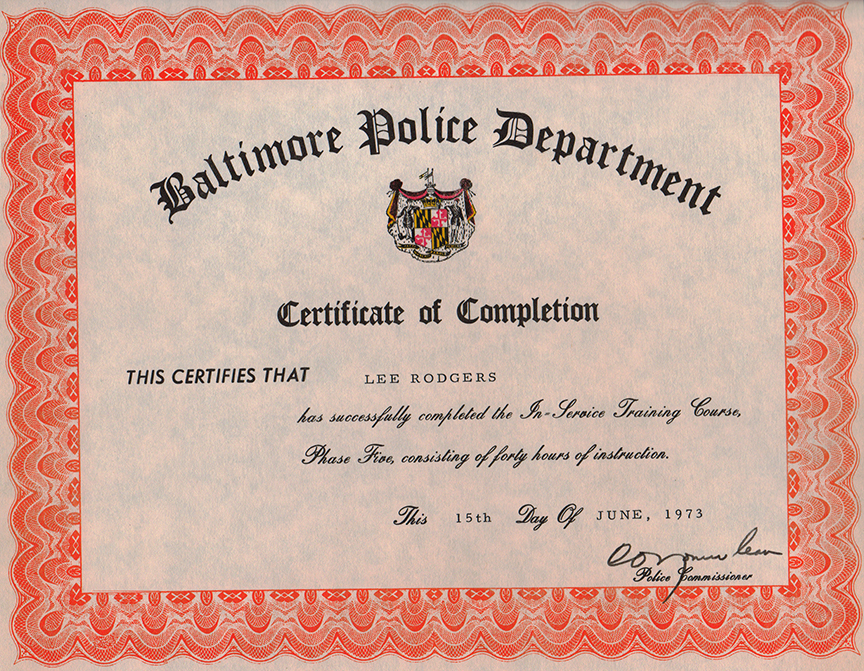

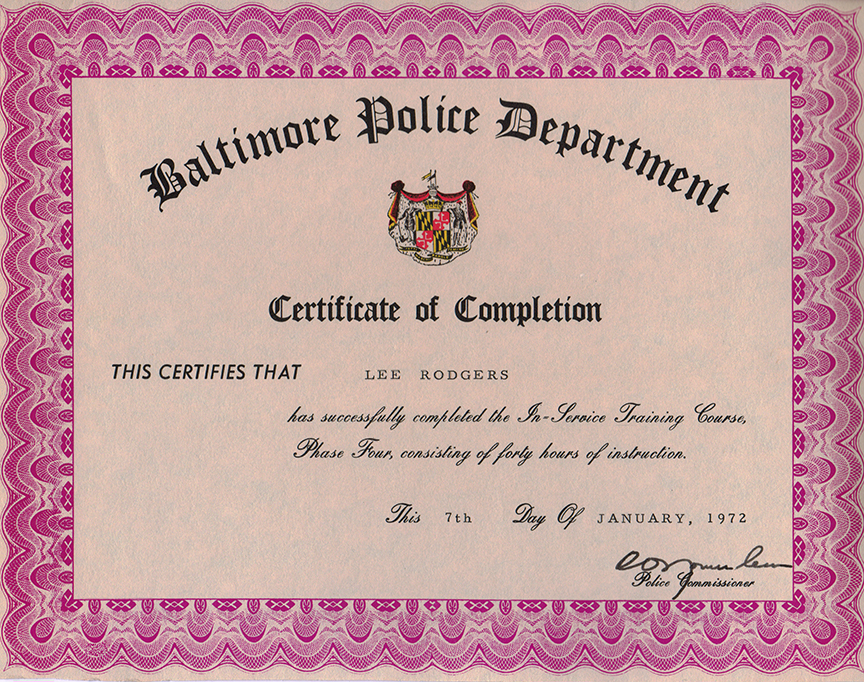

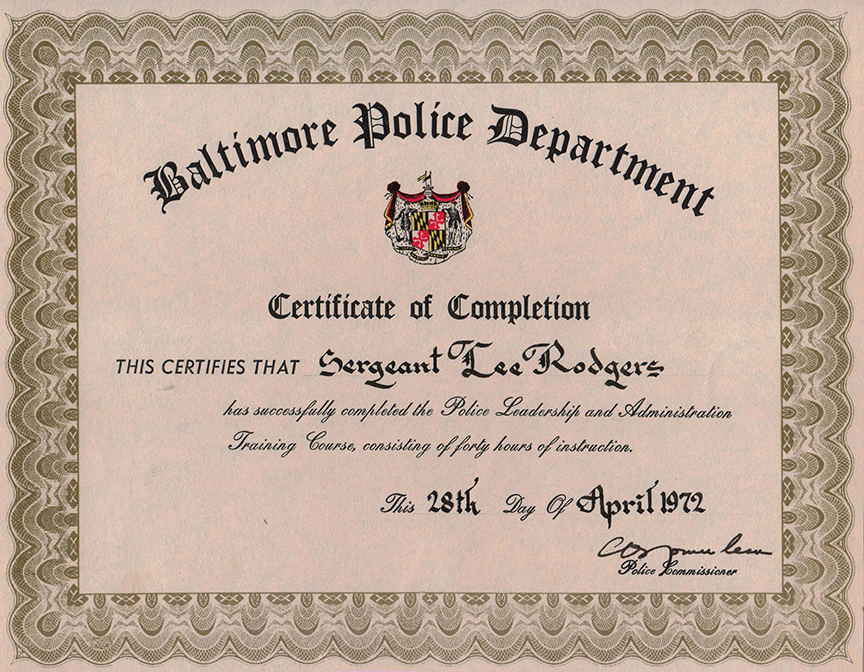

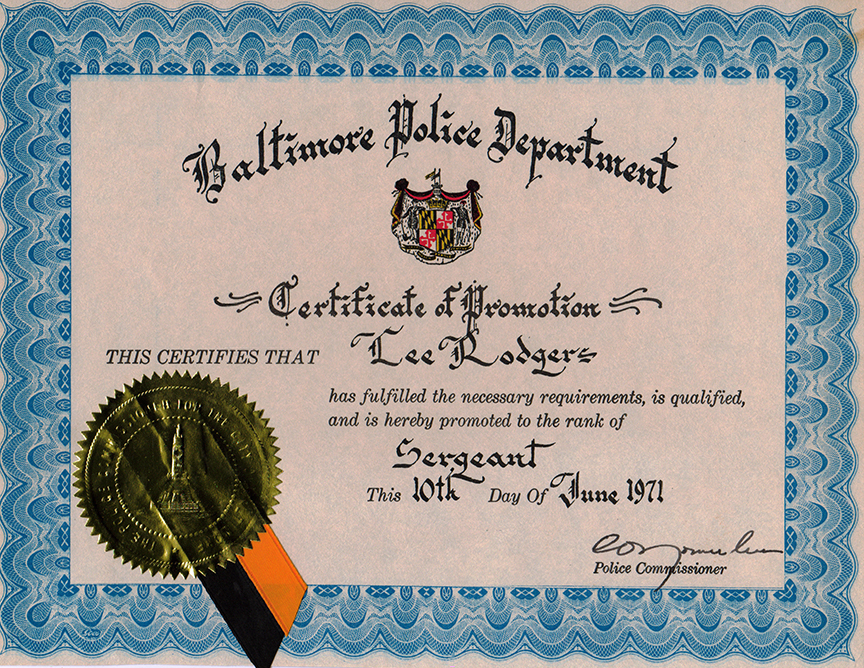

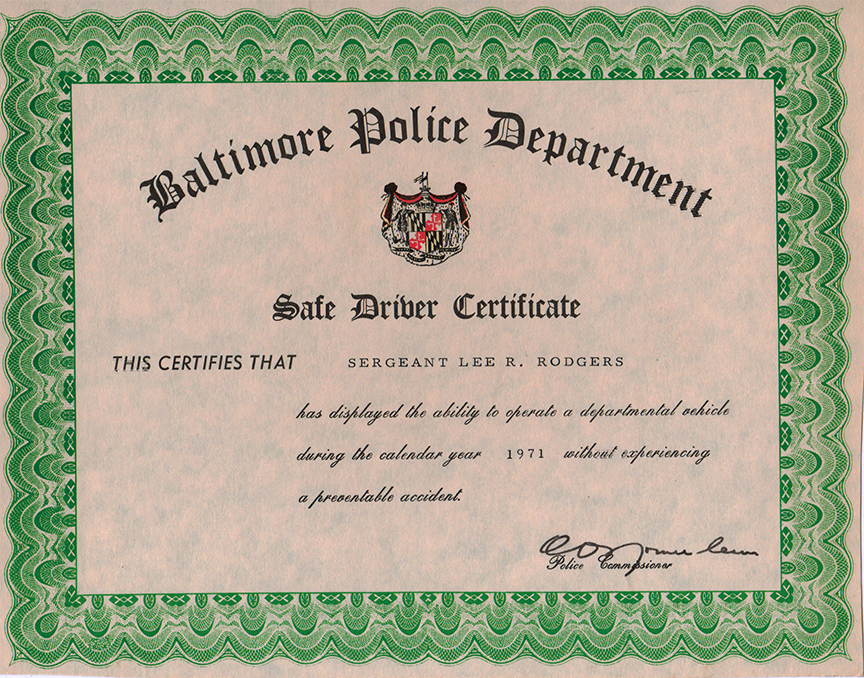

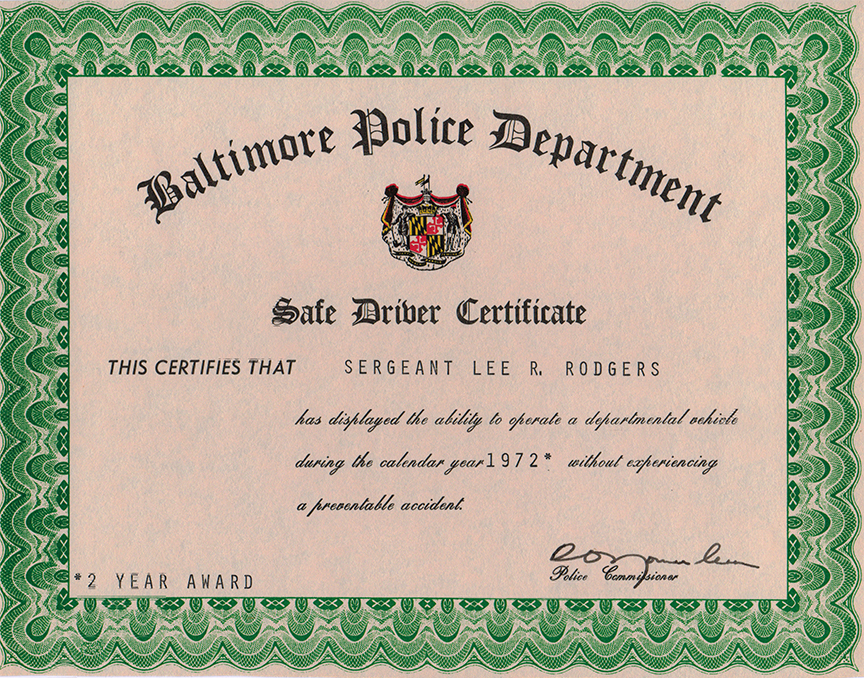

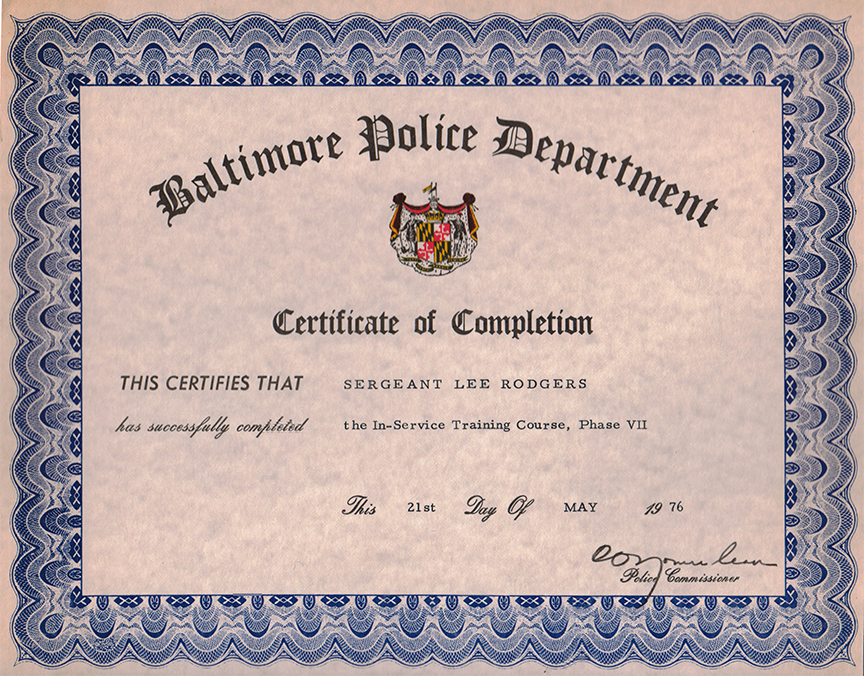

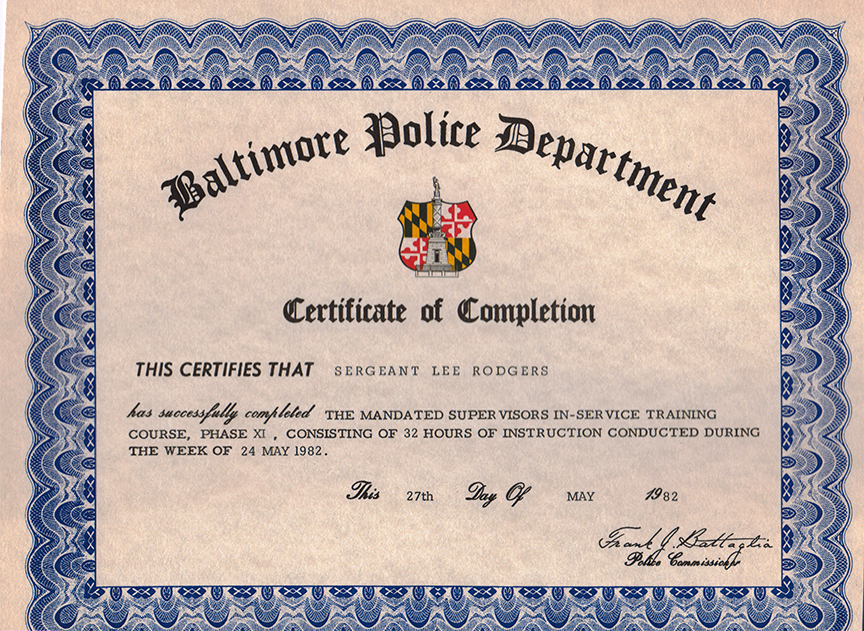

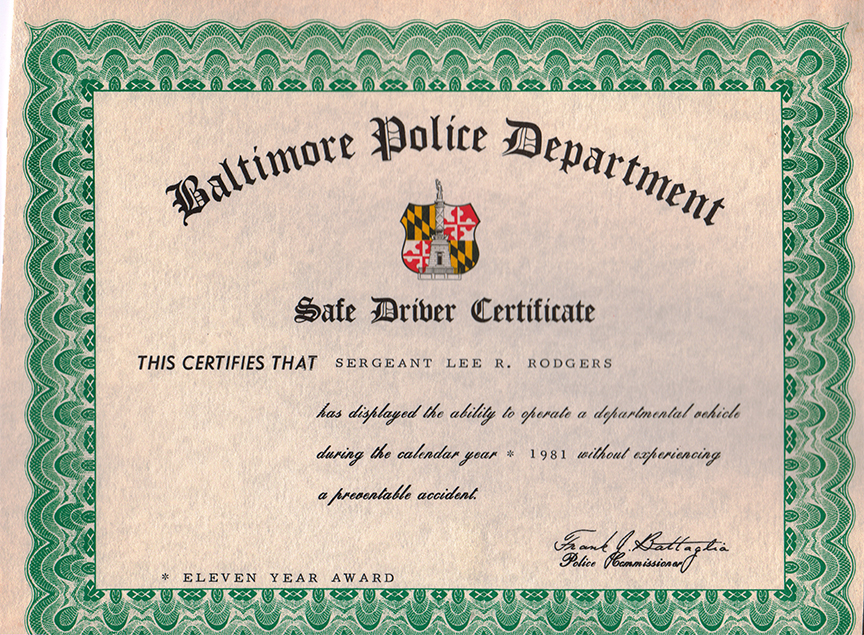

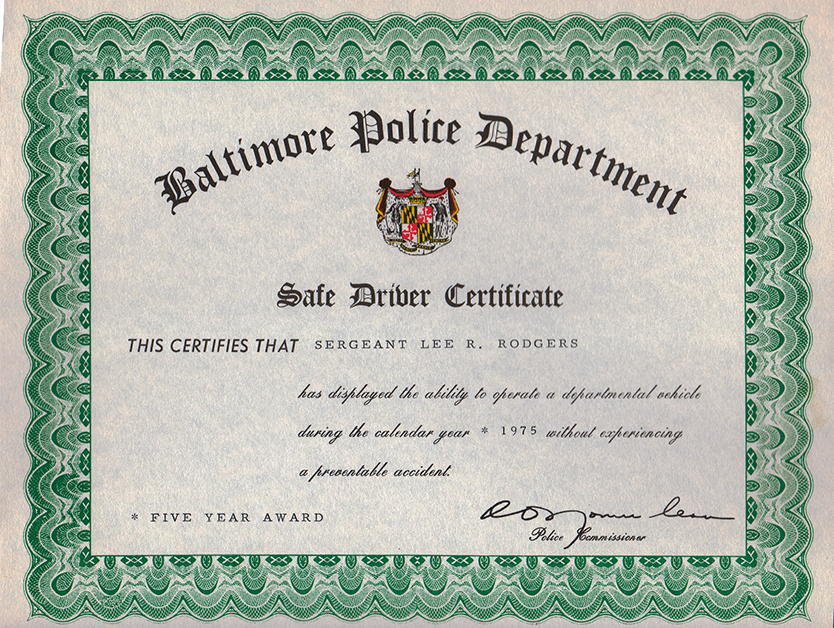

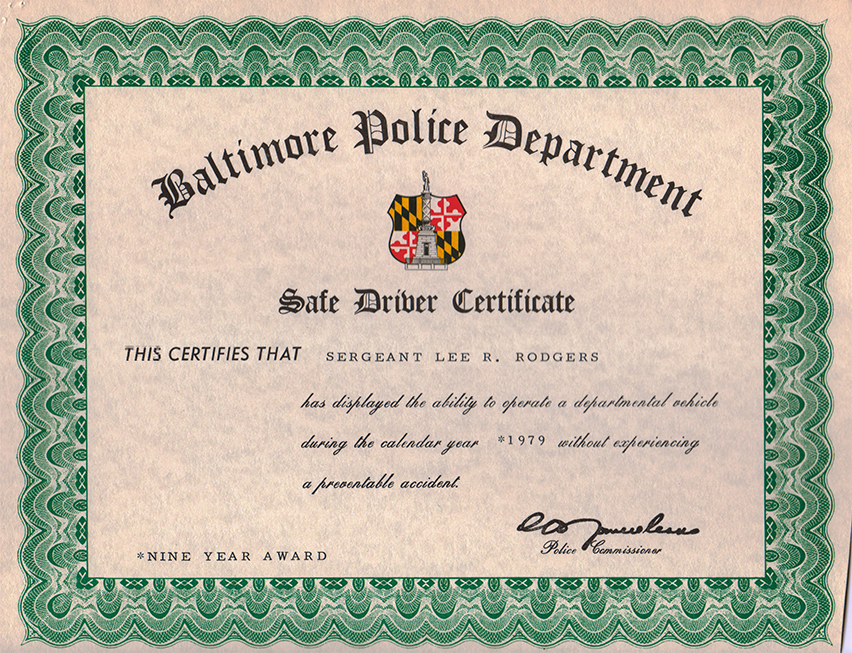

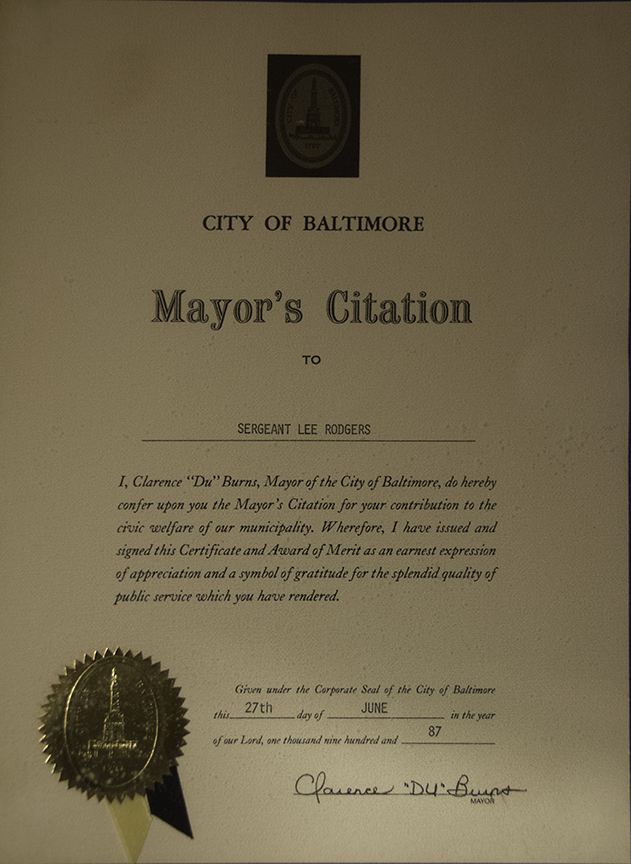

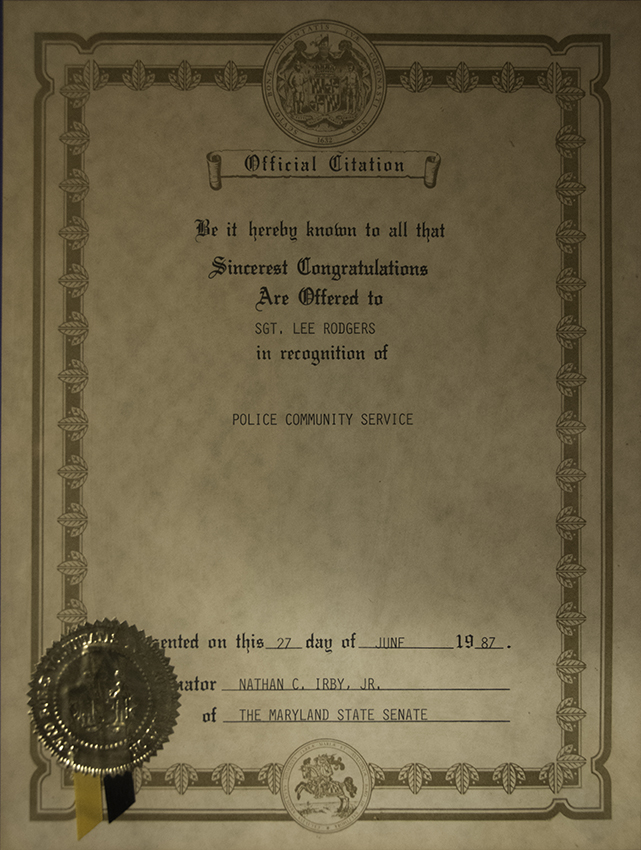

Photo Courtesy of Mark Rodgers

Photo Courtesy of Mark Rodgers Photo Courtesy of Mark Rodgers

Photo Courtesy of Mark Rodgers Photo Courtesy of Mark Rodgers

Photo Courtesy of Mark Rodgers Photo Courtesy of Mark Rodgers

Photo Courtesy of Mark Rodgers Photo Courtesy of Mark Rodgers

Photo Courtesy of Mark Rodgers

Photo Courtesy of Mark Rodgers

Photo Courtesy of Mark Rodgers

First Electric Traffic Signal installed in Baltimore City at the Mall Crossing in Druid Hill Park. It was installed in place of the old manually operated Go-Go signals, and was first operated by Baltimore Park Police Officer R. W. Wilson on 6 May 1921

First Electric Traffic Signal installed in Baltimore City at the Mall Crossing in Druid Hill Park. It was installed in place of the old manually operated Go-Go signals, and was first operated by Baltimore Park Police Officer R. W. Wilson on 6 May 1921.jpg)

1920 Semaphore

1920 Semaphore

Traffic booth and Officers directing traffic at Liberty and Lexington Streets

Traffic booth and Officers directing traffic at Liberty and Lexington Streets