Capt J. Lyston

Capt. Jimmy Lyston

Excerpts from “The Lyston's – A Story of One Baltimore Family and Our National Pastime” by Jimmy Keenan

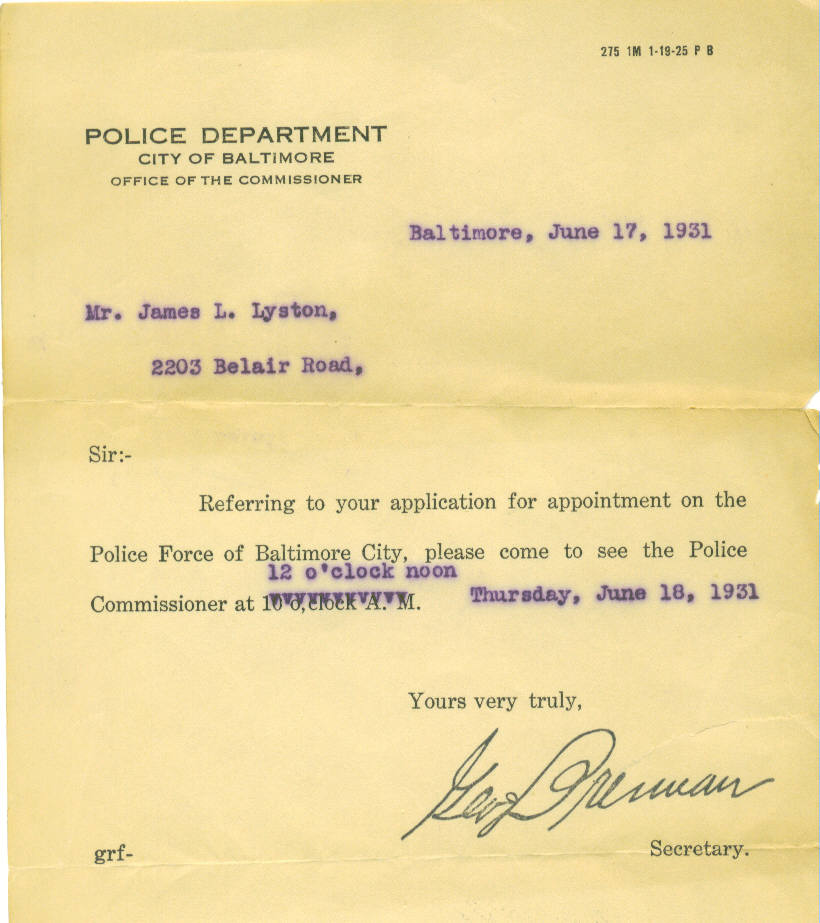

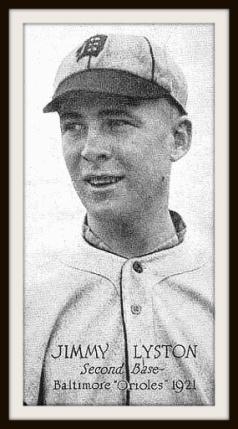

Jimmy Lyston was born in the Waverly section of Baltimore, Maryland on January 18, 1903. He was the youngest of four children born to John M. Lyston [a former major league baseball player and U.S Customs Inspector] and Katherine Josephine Concannon Lyston. John M.’s two brothers. Bill and Morty, were also professional baseball players. Jimmy attended St. Ann’s Grammar school and later Loyola High School where he played on the football and baseball teams. He signed his first professional baseball contract with Jack Dunn’s International League Baltimore Orioles in early January of 1921 at the age of 17. Jimmy Lyston married the former Edith Wade on December 26, 1929 and the couple had two daughters, Peggy born in 1930 and Nancy born in 1942.

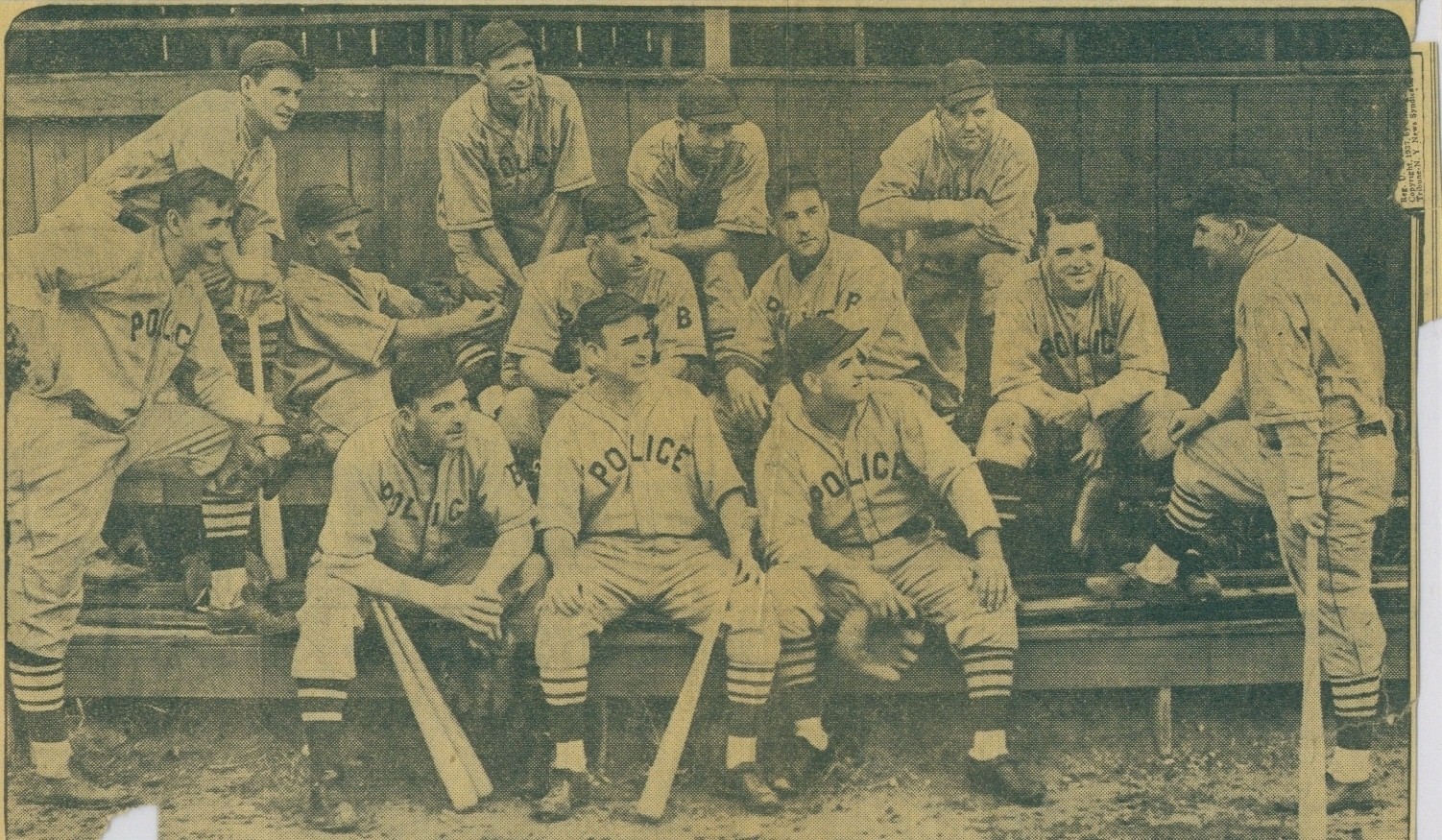

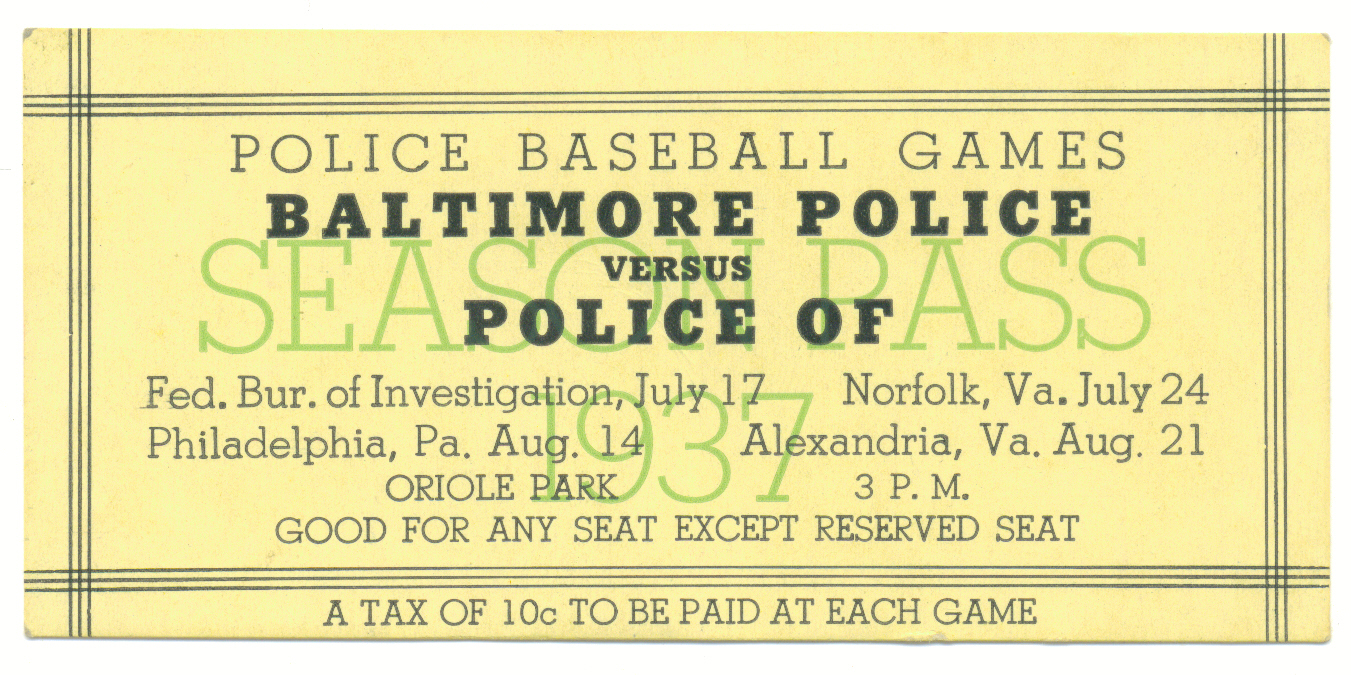

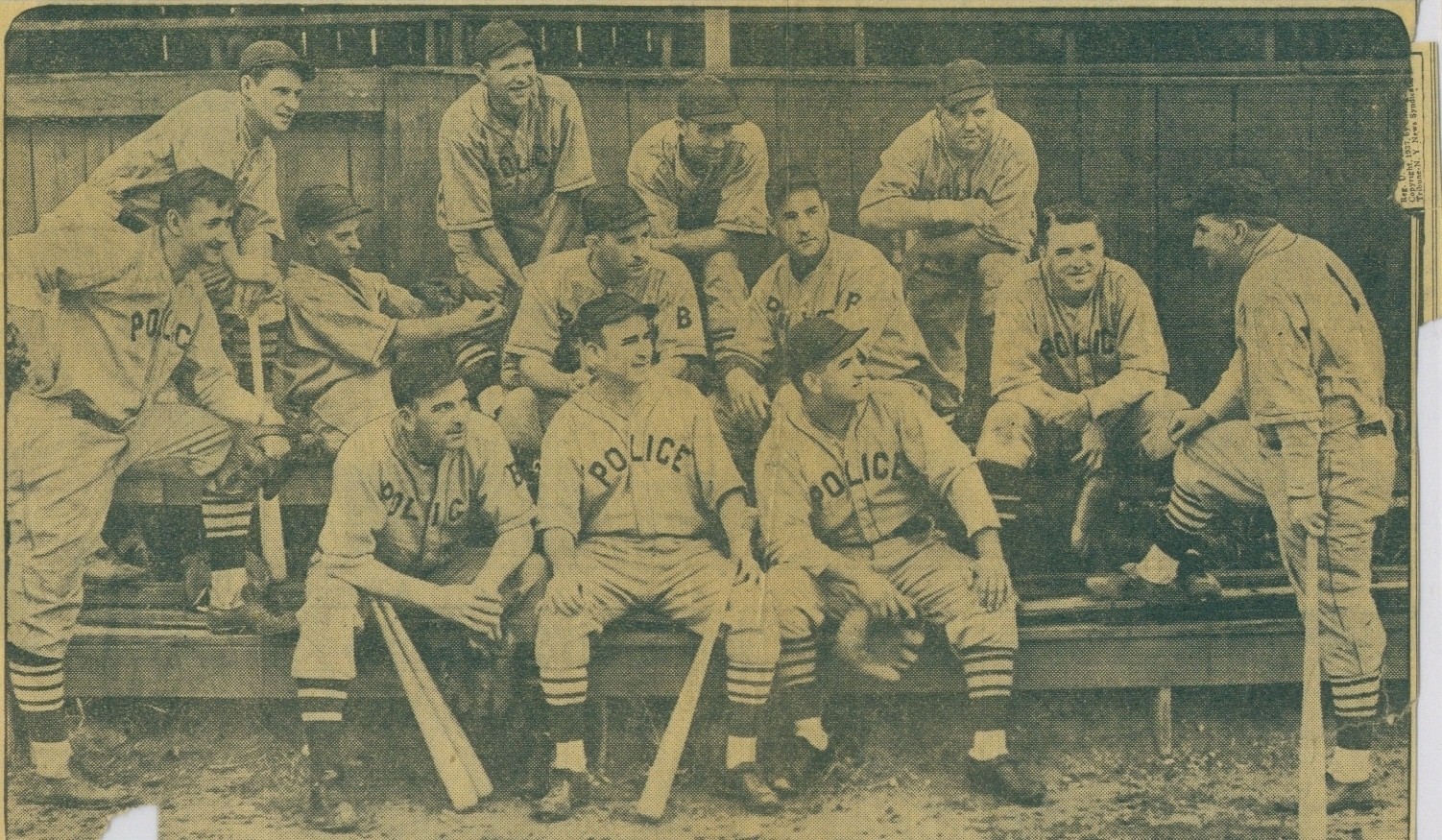

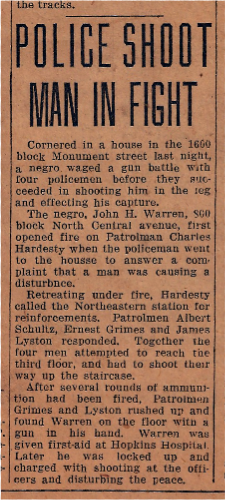

Lyston played professional baseball until June of 1931. At that time, he resigned from the Hagerstown Hubs of the Middle Atlantic League to become a Baltimore City Police officer. In 1924, the Baltimore City Police Department, at the behest of Commissioner Charles D. Gaither, formed an All-Star baseball team that was made up of the best ball-playing policemen from each district. Nearly all the members of the ball club were former professional baseball players. Jimmy Lyston played on the Baltimore Police baseball team from July of 1931 until it was disbanded by Commissioner Robert F. Stanton in the spring of 1940. During that time, the Baltimore City Police baseball team played against the best semi-pro and amateur nines in the city, winning numerous championships. They also competed against police departments from other cities including J.Edgar Hoover’s F.B.I. baseball team in what was called the John Law Series. Baltimore came out on the winning end of the series on most occasions.

Noted Baltimore sports figure Charlie Eckman was the police team’s bat boy during the 1930’s. In his book, “It’s a Very Simple Game,” Eckman reminisced to his biographer Fred Neil about the talented Baltimore City Police baseball club. The following is the article from Mr. Eckman’s outstanding book:

![]()

An Arresting Team on The Local Diamond

One of the best amateur baseball teams in Baltimore during the thirties according to Eckman was the Baltimore City Police Department team. They would play other amateur teams during the week but on the weekends the players would scatter to play for top-notch semi pro teams to pick up $10 to $15 a game. That was a lot of money in those days.

Eckman: “These guys were outstanding ballplayers and they gave any team they played fits. They had a tough group of pitchers like Hen Sherry, Buck Foreman, Bill Runge, Harry Biemiller and others. The catchers were Johnny Alberts, Joe Koenig and Pete Stack. Around the infield was Hoby Hammen on first … Jimmy Lyston on second…. Eddie Sawyer played shortstop … Tony Schoenoff on third. Their top backup infielder was“Inky” Graff. Patrolling the outfield were, (no pun intended), George Klemmick in centerfield, with Joe Zukas in left…Augie Schroll was in right, with Freddy Fitzberger off of the bench. The other guys were good but these are the guys that stand out in memory. Sergeant Polly Martin was the manager, but the guy who ran the team was Captain “Buck” Hartung.”

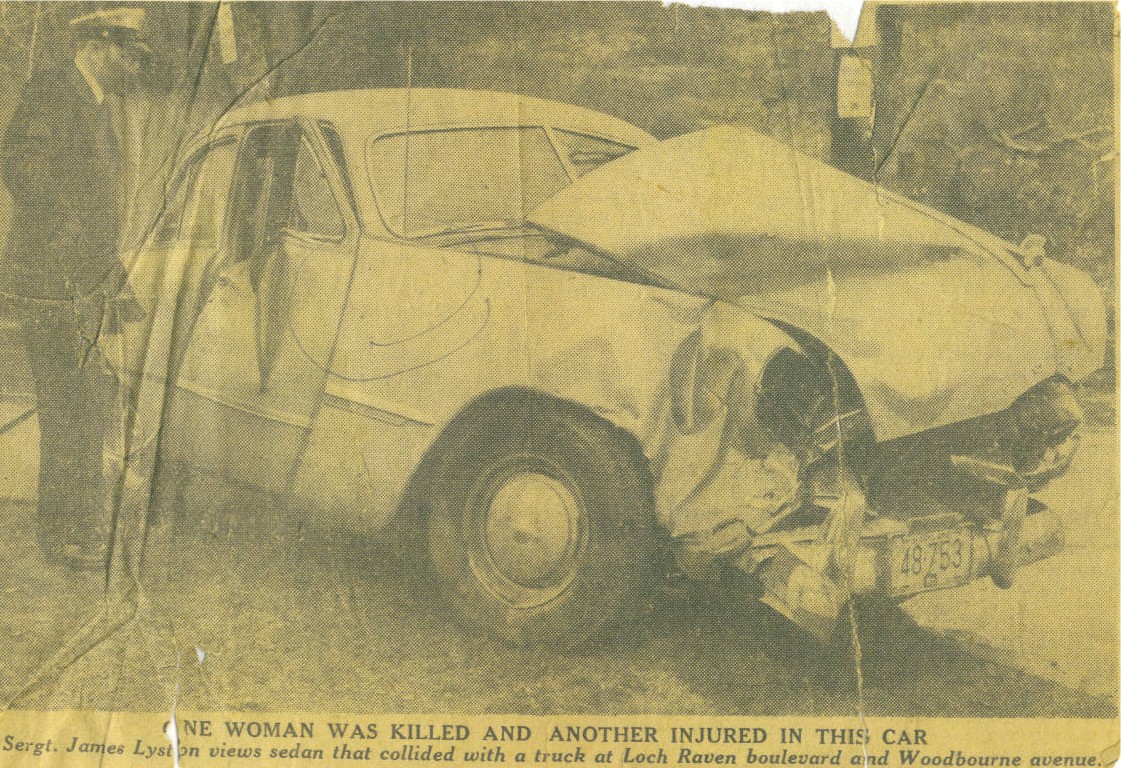

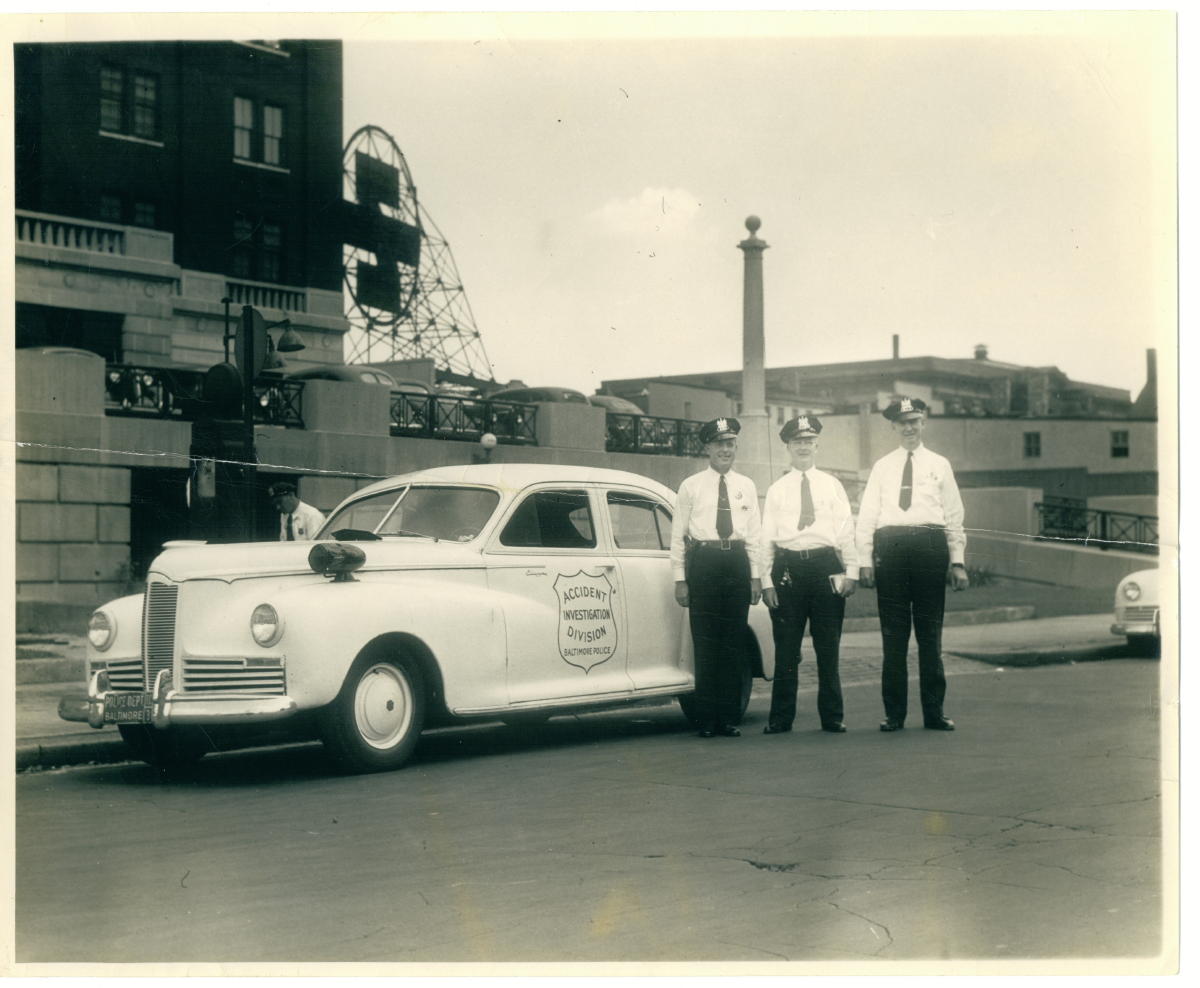

Jimmy Lyston began his career in law enforcement off of the diamond as a patrolman in the old Northeastern District on June 18,1931. He joined the Accident Investigation Division in November of 1939. His duties at this time involved investigating hit and run automobile accidents in Baltimore city. The majority of these accidents involved fatalities. On many occasions, he was able to locate the driver through good old-fashioned police work.

The following are the accounts of three of these hit and run accidents in which he and his partner received a commendation for solving the case:

On November 12, 1941, two cars hit two pedestrians at the same time in the 2400 block of Madison Avenue. Police officers Jimmy Lyston and Wilmer Lerian had very little help from any of the eyewitnesses. However, a witness was able to recall that one of the cars had whitewall tires. Officer Lerian was the brother of major league catcher, Walter “Peck” Lerian. The only piece of evidence that the two policemen were able to find at the accident scene that day was a broken off headlight ornament. Unfortunately, one of the injured pedestrians would eventually die the next day. The two officers eventually located two suspicious vehicles about three blocks from the accident scene in a public garage. Both car owners denied any involvement in the crime. The headlight ornament that was missing from one of the cars sealed their fate. The owners of both vehicles were arrested.

The commendation read: “In view of the inadequate description of the automobiles by the witnesses, the officers were compelled to overcome almost insurmountable obstacles; they nevertheless were successful in convicting both drivers.”

On December 1, 1941, a pedestrian was killed in a hit and run accident at the corner of Philadelphia Road and Erdman Avenue in Baltimore. There were no witnesses and the only piece of evidence was part of a radiator grill that was left at the scene. Police officers, Jimmy Lyston and Thomas Keyes, located a commercial truck parked several blocks away with a piece of radiator missing. The ignition switch had been hot-wired to make the truck appear to have been stolen. While questioning the company’s employees, the police officers determined that there were discrepancies in one of their statements. The guilty man eventually confessed.

The commendation read: “In view of the fact that there were not any witnesses and while all indications pointed to the fact that the vehicle was stolen, nevertheless the officers initiative and meritorious investigation resulted in most satisfactory handling of the case.”

On December 14, 1942, at 6:05 PM, an accident occurred at the intersection of Saratoga Street and Fremont Avenue in Baltimore city. The incident involved two pedestrians who were struck by a car and seriously injured. One of the victims was carried on the hood of the automobile for a distance of four and a half blocks before falling off the vehicle and left lying in the middle of the street. The operator of the vehicle failed to stop after the accident. The only information the police received concerning this hit and run car was that it bore Maryland tags, the first three numerals which may have been 177. Also found at the scene of the accident were fragments of headlight glass, presumably belonging to a 1931 Chevrolet. Patrolmen James L. Lyston and Patrolman Thomas J. Keyes checked the Automobile Commissioner’s Motor Vehicle list of over 177,000 vehicles. After exhaustive research, they found a 1931 Chevrolet sedan with MD. License plate 177-914. The driver of that vehicle had recently been arrested for an unrelated drunk driving charge and was being held at the Essex Police Station in Baltimore County. The car was parked on the Essex Police parking lot. The broken headlight glass at the accident scene matched the fragments of glass that were left on the vehicle. After a drive to the Essex Police Station and a check of the back lot, the Baltimore Police had their culprit. The guilty man was sitting in the Essex Jail. There was no way for the Essex Police to have known about the previous accident.

The commendation read, “For their careful investigation for this unusual accident and their diligence in locating the suspect in another jurisdiction and for their careful investigation of this and subsequent apprehension and conviction in the City.”

Jimmy Lyston received thirteen commendations during the course of his 33- year career in the Baltimore City Police Department.

My Grandfather also described to me what went on during the air raid drills that occurred in Baltimore during World War II. During these blackouts, Baltimoreans were required to stop everything and pull all the window shades down and turn off all lights.

My Granddad told me about the first time that the Baltimore City Police Department tested a tear gas gun. He said the gun had such a tremendous kick that nearly everyone who took a shot with it was knocked to the ground by the recoil.

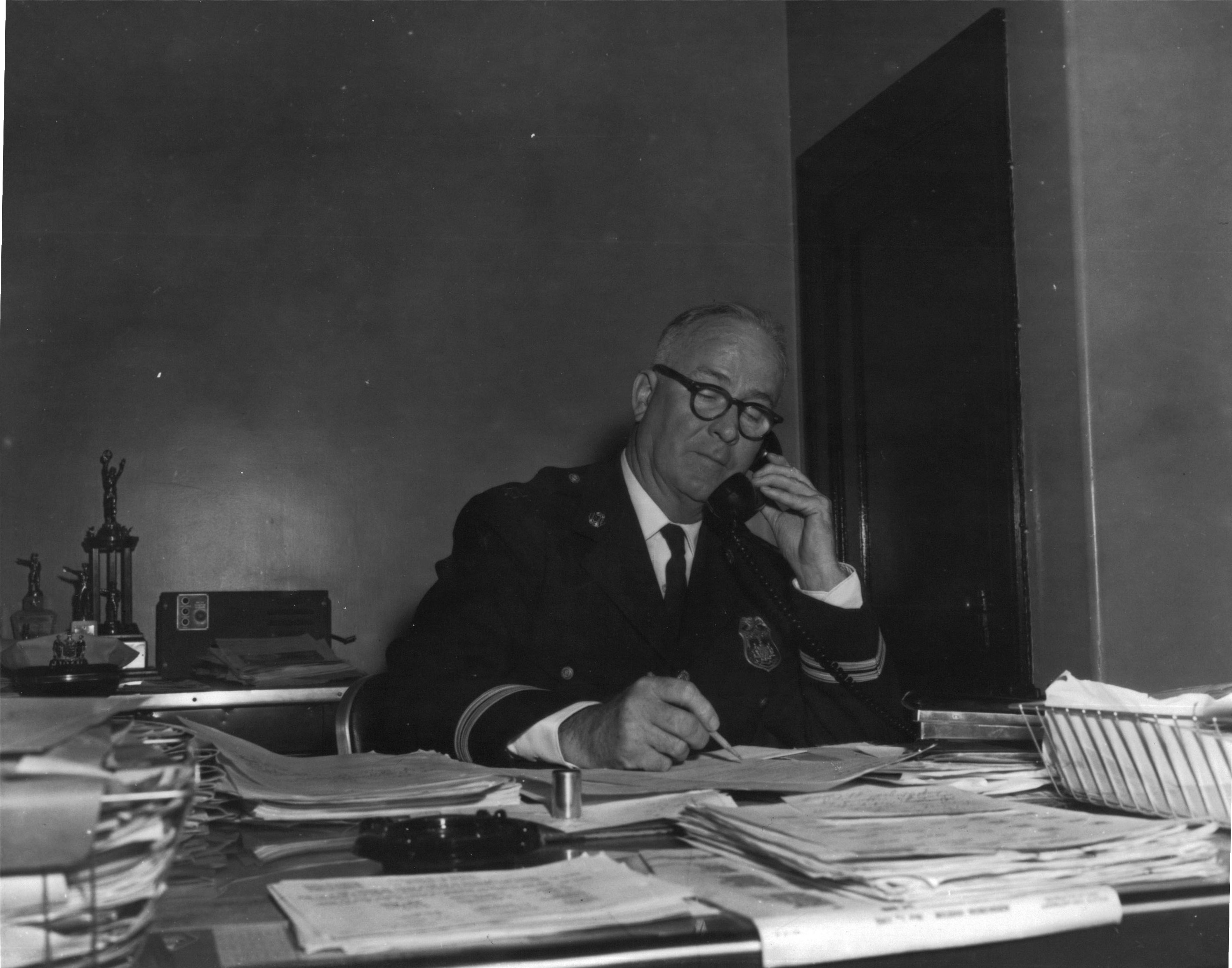

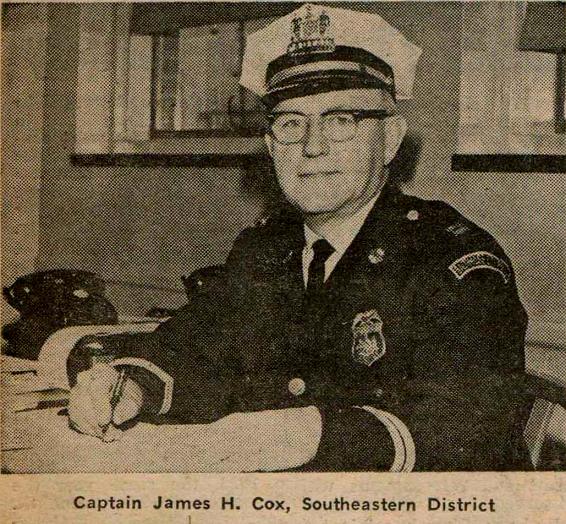

Jimmy Lyston was a member of the Baltimore City Police Riot Squad. An outstanding shot with a pistol, he was also a member of the competitive shooting team. Promoted to Sergeant on January 30, 1947, he made Lieutenant on May 6, 1954, and by May of 1960, the former professional baseball player had attained the rank of Captain. This was before the military designations of Colonel and Major were introduced into the Baltimore City Police Department’s officer ranking system.

The Baltimore Evening Sun of May 5, 1960, stated, “Lt. James Lyston commended thirteen times for meritorious service in 29 years with the Baltimore Police department was today promoted to Captain.

Captain Lyston, a professional baseball player before joining the force in June of 1931, has been placed in charge of the Motor Vehicle Traffic Squad.”

Captain Lyston’s promotion was mentioned by noted Hagerstown sportswriter Frank Colley in his column the following day:

The Hagerstown Morning Herald of May 6, 1960, noted, “After 29 years of service with the Baltimore Police Department during which time he was commended thirteen times for meritorious service, Lt. James L. Lyston was promoted to the rank of Captain and has been placed in command of the motor vehicle traffic squad.

To many readers of this column the name of Lyston doesn’t register but to those who followed the old Blue Ridge League back in the 1920’s it will click.

Jimmy Lyston as he was known to fans in this city and around the circuit especially in Waynesboro was one of the best infielders ever to grace a Blue Ridge League diamond.

Possessing a great pair of hands and while not a heavy hitter, he was a timely clouter and one that was hard of keep off of the bases.

Jimmy quit baseball in 1931 and joined the Baltimore Police force and has held down quite a number of official positions. Those remembering Jimmy wish him the best of luck in his new post and congratulations on his promotion.”

Captain Jimmy Lyston was the commander of the motorized section of the Baltimore City Police Department’s Traffic Division from May of 1960 to October of 1964. His command was composed of all of the motorcycle and mounted policemen in Baltimore City. At that time, even some city taxicabs were under the Police Department’s jurisdiction.

In the fall of 1962, President John F. Kennedy visited Baltimore to speak at a Democratic rally that was being held at the Fifth Regiment Armory.

In the early evening hours of October 10, 1962, President Kennedy and his entourage departed from Washington, D.C. in a convoy of four Marine helicopters. The choppers landed at Patterson Park in east Baltimore a short time later.

The presidents scheduled trip was highly anticipated by the local citizens and there were over 30,000 people at the park to get a look at the President. Senate hopeful, Daniel Brewster, along with Senators Garmatz and Fallon, flew inthe helicopter convoy with the President.

Many of Baltimore’s prominent Democrats were in the crowd including Governor Tawes, Mayor Grady and City Comptroller Louis Goldstein. Captain Jimmy Lyston and most of Baltimore’s high- ranking police officers were positioned at the park to meet the President.

When the Presidential helicopter landed at the park, the Commander-in-Chief disembarked and ran briskly to his waiting vehicle with Secret Service agents close behind. My Granddad made mention of the fact the President never wore a hat, which most men did at that time. President Kennedy’s blue Continental convertible had been driven over from Washington, D.C. for the occasion. Tragically, this would be the same vehicle in which the President would be assassinated in just over a year later.

President Kennedy’s Baltimore motorcade pulled out from Patterson Park and headed west on Eastern Avenue. All of the motorcycle policemen in President Kennedy’s motorcade that day in Baltimore were under the command of Captain Lyston. The procession then made a right turn at Washington Street, proceeded north a few blocks and made a left turn at North Avenue. It then moved west on North Avenue to another left at Howard Street. The motorcade then headed south on Howard Street and made a right into the Fifth Regiment Armory’s parking lot. There were crowds lined up with cheering people three rows deep all along the route of the motorcade.

The Baltimore Sun of October 11, 1962, stated that 1 out of 5 of the city’s 1,000,000 inhabitants had come out to see the President. It also stated that there were 1,400 local police officers on duty that night. There were 8,000 people packed in the Armory and another 12,000 people outside of the building. There were loud speakers hooked up to the exterior of the Armory so everyone outside could hear the speeches. Former Mayor Tommy D’Alesandro was the Master of Ceremonies for the event.

The Democrats were only able to purchase a limited amount of TV and radio time for the event. To be fair, each member of the Statewide Democratic ticket was given a chance to speak at the podium. The candidates spoke quickly and then sat down so the next person could have their turn. When it was President’s Kennedy’s time to speak, he stood up, smiled, and said, “I’ve never seen so many Democrats say so much in so little time.”

In his speech that evening, the President complimented the work of the Eighty- Seventh Congress that was in session. The President stated that they had just enacted the Trade Expansion Act, and that they had given the go signal for efforts to assure that the United States would be first in the space race by 1970. He then spoke a few complimentary words about each candidate that was in attendance that evening before finally wrapping it up. The President’s speech lasted about six minutes.

At the conclusion of the rally, Captain Lyston got a chance to speak with President Kennedy at the armory. The two shook hands, the President telling Captain Lyston how impressed he was with the fine job that the Baltimore City motorcycle policemen had done in leading the motorcade to the Armory.

The leader of the free world and his entourage got back in their cars and the motorcade proceeded back to Patterson Park where they returned to Washington D.C. by helicopter. The President was in Baltimore for a total of one hour and twenty- two minutes. My Grandfather told me that meeting President Kennedy was one of the highlights of his police career.

On a darker note, there was actually a threat made on the President’s life prior to his trip to Baltimore. The day before the President’s arrival, a local newspaper reported that it had received an anonymous phone call from someone threatening to assassinate the President while he was in Baltimore.

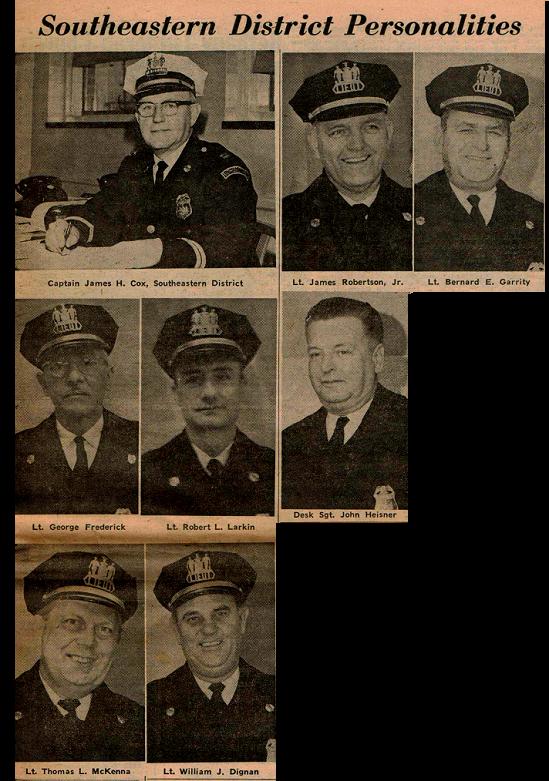

The Baltimore Sun of October 11, 1962, wrote, “Following a threat to kill President Kennedy during his Baltimore visit, police yesterday arrested a 27 year old man near Patterson Park where the President’s helicopter landed. The unarmed suspect was picked up in the 400 block South Linwood Avenue about 3P.M. as police and Secret Service men converged in the park to prepare for the President’s arrival.

He was taken to the Southeastern police station and booked for investigation. Police continued to hold him last night without placing any charges.

The arrest followed a telephoned threat on the President’s life that was made to a newspaper earlier in the day.

A man with a husky voice said, “I’m going to shoot President Kennedy tonight in the parade.”

Police said the man in custody first claimed to be an undercover agent, and then said he was a newspaper reporter. They were unable to link him immediately with the threatening phone call.

More then 1,400 local policemen were on hand to protect Mr. Kennedy during his brief Baltimore stay.”

Thanks to the great work and keen observation of the Baltimore City Police Department, President Kennedy remained safe during his visit in Baltimore.

Captain Lyston was a member of a Baltimore City Police Commission that was involved with determining the practicality of building Baltimore’s Harbor Tunnel Thruway. The Harbor Tunnel was eventually opened to the public in November of 1957.

In regard to driving safety, Captain Lyston was instrumental in having the painted white line on the right hand side of the road being made mandatory in the state of Maryland.

Captain Lyston and other high- ranking Baltimore Police officials rode in the lead cars in all of the Baltimore Parades during his time as commander of the Traffic Division.

Captain James L. Lyston retired from the Baltimore City Police Department in October of 1964 after thirty-three years and four months of dedicated service.

![]()

July 8, 1936: Baltimore police tame the U.S. Olympic baseball team

This article was written by Jimmy Keenan

Baseball was played at the Olympics for the first time as a demonstration sport at St. Louis in 1904; very little information on this game is available. Further Olympic baseball exhibitions took place in 1912 and 1924. Hoping to make baseball a sanctioned medal event, former major leaguer Les Mann petitioned the Olympic Committee to allow him to form a team to play Japan at the 1936 Summer Games in Berlin. In addition to his title of general manager of the Olympic ballclub, Mann was the executive vice president of the American Baseball Congress as well as the dean of Max Carey’s baseball school in Miami. In November of 1934 the Olympic Committee accepted Mann’s offer.

In the fall of 1935, Mann and future Hall of Famer Max Carey took a group of college players, sponsored by Wheaties, to Japan for what turned out to be a successful 20-game exhibition tour. The following summer Mann began the selection process for the US Olympic baseball team. After tryouts around the country, Mann took his Olympic hopefuls to Baltimore in early July for the squad’s final workouts. Each player who made the team was required to put up $500 to cover his expenses.

The head coach of Olympic baseball team was Harry Wolter, the Stanford University head coach. The other coaches and advisers were Dinty Dennis, Miami Herald sports editor; George Laing of the Penn Athletic Club in Philadelphia; Linn Wells, baseball coach at Bowdoin College in Waterville, Maine; and Judson Hyames, baseball coach at Western State Teachers College in Kalamazoo, Michigan. George “Tiny” Parker and veteran baseball scout John “Poke” Whalen were selected by Mann to accompany the team to Berlin as umpires.

The team practiced at Gibbons Field in the Irvington section of West Baltimore. These grounds, which are adjacent to Mount Saint Joseph High School, are now called Slentz Field. In order to give local players an opportunity to make the squad, nearly 60 of Baltimore’s best amateurs were asked to try out. Four teams were selected from this group, then matched up in a doubleheader at Bugle Field in East Baltimore. A dozen of the best players from those two games were placed on a team called the Pimlico All-Stars. On July 4 the Olympians played the All-Stars at the Pimlico Oval. Team USA won the contest 12-9, scoring five runs in the top of the ninth to secure the win. Baltimorean Bill Kidd, star backstop for the Chesapeake Baking Company, caught part of the game for the Olympians.

On July 7, the US Olympic baseball team went to Washington to play a fundraising game against the Quantico Marines at Griffith Stadium. Team USA came out on top 15-2 in front of several thousand patriotic supporters.

The next day the Olympians squared off against the Baltimore City Police Department baseball team at Bugle Field. The Police roster was made up almost entirely of former professional baseball players who left Organized Baseball to pursue a career in law enforcement. The manager of the police team, Polly Martin, chose Edward “Augie” Schroll as his starting pitcher. Schroll pitched for the Cambridge Canners in the Class D Eastern Shore League in 1922. The hard-throwing right-hander posted a 10-9 record with 146 strikeouts while leading the circuit in innings pitched (205). Team USA manager Harry Wolter countered with Eldred Brittsan from Wren, Iowa. Brittsan played two seasons in the minor leagues before joining the US Army in World War II. He was killed on January 28, 1945, while fighting with 80th Infantry Division in Luxembourg.

Mann’s charges took an early 1-0 lead when Grover Galvin drilled Schroll’s second pitch of the game over the right-center-field fence. Unfazed by the early long ball, Schroll retired the next three batters in order. The Police countered with four runs in the bottom of the first on two walks and four hits. Brittsan lasted two-thirds of the inning before being relieved by University of Nebraska pitcher Bill Sayles. A tall right-hander, Sayles later pitched for three major-league teams.

From that point on the Police never relinquished the lead, eventually coming out on top 9-5. Schroll worked seven innings for the police, giving up four runs while walking three and fanning five. Bill Runge pitched the eighth and ninth, allowing one run on two hits. Runge was a 14-game winner for the Youngstown Buckeyes in the Class B Central League in 1932. Hard-throwing Fred Heringer from the University of Nebraska pitched the last four innings of the game for Team USA, holding the Police to one final run. Of Heringer, the Baltimore Sun wrote, “He is a right-hander with plenty of smoke and looked like the best hurler Mann has on his staff.”1

The Police held the Olympians to just six hits. Second baseman Les McNeese went 1-for-3 with a double. McNeese, who replaced Galvin at second base early in the game, was a standout player from the Fort Lauderdale, Florida, area. Shortstop Dow Wilson, from Dover City, Iowa, connected for a pair of singles. Iowa native Galvin, Hubert Shaw of Bowdoin College, Paul Amen from the University of Nebraska, and Don Hibbard from Western State Teachers College all had one hit.

Police third baseman Jimmy Lyston and center fielder George Klemmick each contributed two hits for the victors. Lyston broke into professional baseball in 1921 with Jack Dunn’s Baltimore Orioles in the Double-A International League. Lyston was playing for Joe Cambria’s Hagerstown Hubs in the Class C Mid-Atlantic League in June of 1931 when he resigned to join the Baltimore police force.

Klemmick was a pitcher and batterymate of catcher Jimmie Foxx on the 1924 Easton Farmers in the Class D Eastern Shore League. Both were signed by the Philadelphia Athletics at the end of the season. On April 25, 1924, Klemmick had struck out 21 Severn batters while pitching for Polytechnic High School in Baltimore.

Schroll, who played the infield when he wasn’t on the mound, helped his cause with two safeties in three trips to the plate.

Henry Sherry, another member of the police squad, was a former pitcher-infielder-outfielder in the Class D Blue Ridge League. He and Runge pitched as the police team captured two pennants in 1936. The first was in the local Inter-club League, where the Blue-coats finished with a record of 14-3. The second championship was earned in what was called the John Law Series, games played between police-department baseball teams from Baltimore, Washington, Alexandria, Virginia, Norfolk, Virginia, and the FBI. All the teams had players with professional baseball experience so this was always a hard-fought series.

Surprisingly, no Baltimoreans were chosen to play on the Olympic baseball team. Edwin Mumma from Sharpsburg, Maryland, worked out with Team USA during the practice sessions, but he didn’t make the trip to Berlin, presumably due to an injured ankle. The Baltimore Sun noted that the Olympic squad included five members of George Laing’s Penn Athletic Club. Baseball-Reference.com shows that four of the 21 members of the Olympic baseball squad were from Wolter’s Stanford team.

On July 15 the US Olympic delegation left New York for Germany aboard the steamer Manhattan. The Japanese were scheduled to play an exhibition game against Mann’s club in Berlin but they somewhat belatedly decided to withdraw from the competition. Japan did, however, send a group of athletes to Germany to compete in other Olympic sports. The reason for canceling the baseball game lies somewhere in the chilly relationship between Washington and Tokyo at this time. This rift was due to a variety of issues including recent upheaval in the Japanese government caused by an attempted coup, as well as the country’s harsh military policies in East Asia.

On the evening of August 12, the US team played an intrasquad demonstration game on an all-grass field inside a running track at the dimly lit Olympic Stadium in Berlin. The two teams, named the World Champions and the U.S Olympics, played seven innings with the Champions coming out on top, 6-5, on a walk-off homer by Les McNeese. The crowd was estimated to be anywhere from 90,000 to 125,000.

America’s national pastime made such a favorable impression on the Olympic directors that the sport was scheduled for inclusion at the 1940 Games in Tokyo. The Games were canceled because of World War II.

Baseball was played in single-game demonstrations again at the 1952, 1956, and 1964 Olympics. Still not a sanctioned medal event, the first Olympic baseball tournament was held in 1984, followed by a similar competition in 1988. Finally in 1992, baseball became an official Olympic medal sport. The sport’s tenure on the world stage would turn out to be short-lived. In 2005 the International Olympic Committee eliminated baseball and softball after the 2008 games in Beijing. As of 2016, the Olympic ban on both sports was still in effect.

Author’s note - Baltimore Police third baseman Jimmy Lyston was the author’s grandfather.

![]()

POLICE INFORMATION

Copies of: Your Baltimore Police Department Class Photo, Pictures of our Officers, Vehicles, Equipment, Newspaper Articles relating to our department and or officers, Old Departmental Newsletters, Lookouts, Wanted Posters, and or Brochures. Information on Deceased Officers and anything that may help Preserve the History and Proud Traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to Honor the fine men and women who have served with Honor and Distinction at the Baltimore Police Department.

Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll