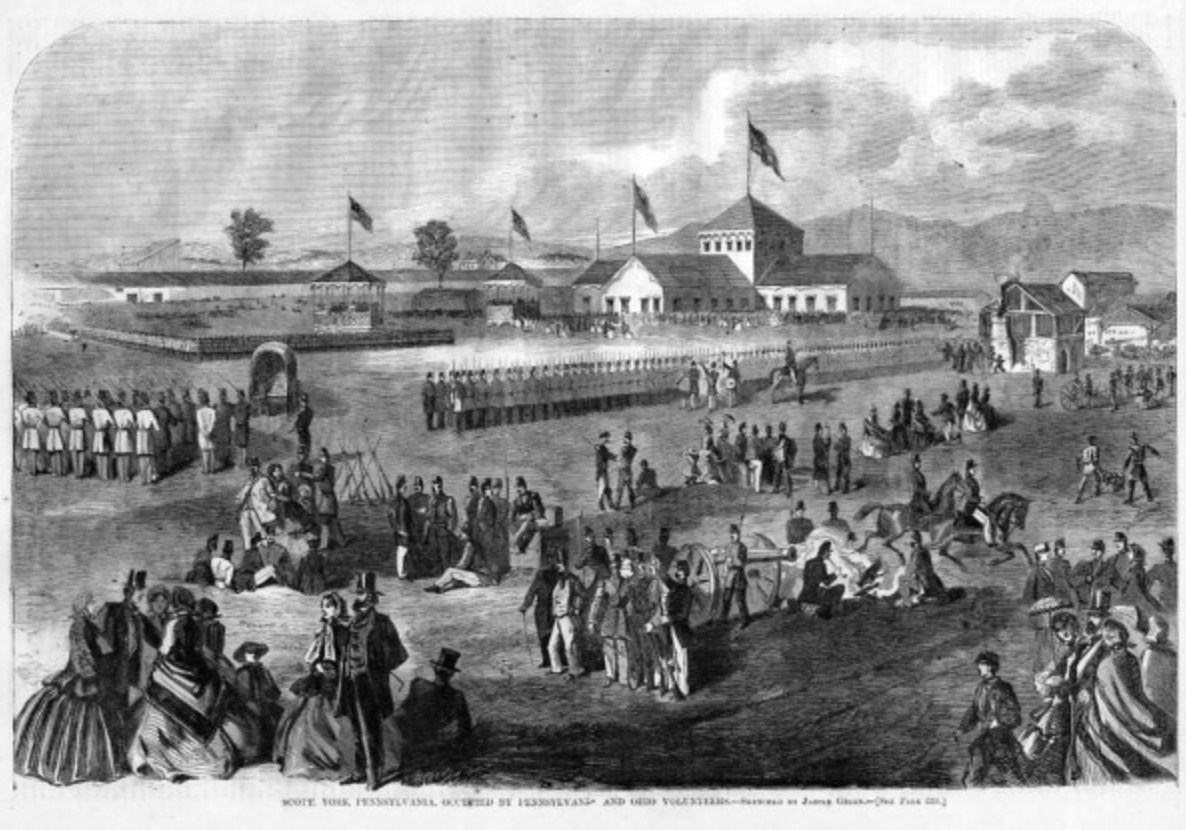

On April 18, 1861, two companies of US Artillery and four companies of militia arrived from Harrisburg at the Bolton Station, in the northern part of Baltimore. A large crowd assembled at the station, subjecting the militia to abuse and threats. According to the mayor at the time, “An attack would certainly have been made, but for the vigilance and determination of the police, under the command of Marshal Kane.”

“I’ll eat when I’m hungry and drink when I’m dry.

And if the Johnnies don’t kill me, I’ll live till I die.”

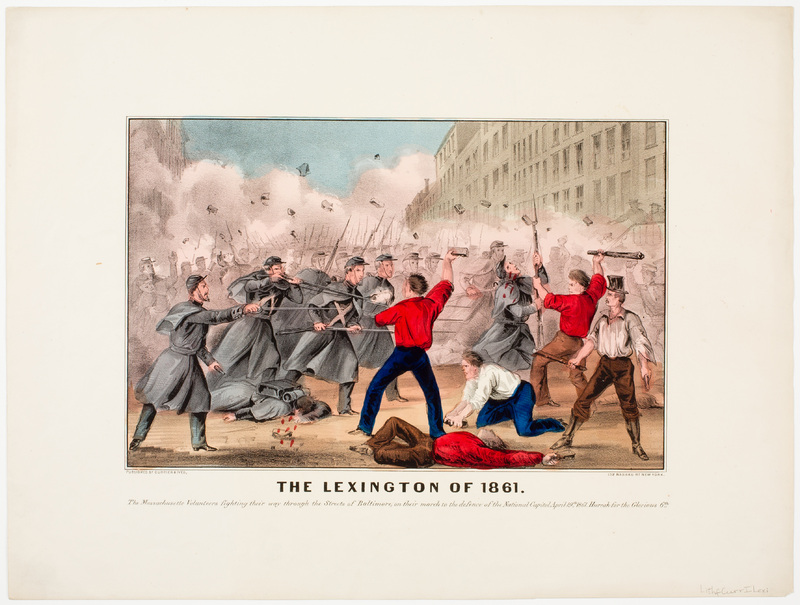

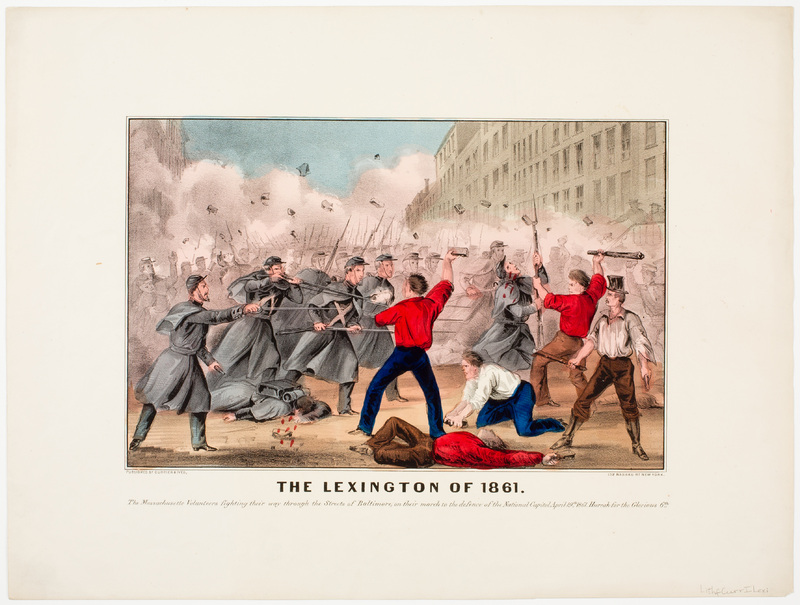

The Lexington of 1861

In many cases, visual resources not only provided a means by which to depict a news event, but also a way to interpret that event. This lithograph, produced by Currier & Ives, shows the Sixth Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment fighting its way through a mob in the streets of Baltimore, attempting to reach Washington, D.C., in answer to Lincoln’s call for seventy-five thousand troops after the firing on Fort Sumter. Sixteen people died in the riot, including four of the Massachusetts soldiers, considered the first combat fatalities of the Civil War.

Comparisons between this riot and the Battles of Lexington and Concord — hence the title The Lexington of 1861 — were swift and inevitable: they both happened on 19 April 1861, involved Massachusetts men, and resulted in the first fatalities of the war. And, as the Union would have it, in both cases the Massachusetts men were simply going about their business when they were ruthlessly attacked by the aggressor. The subtitle of the print states: “The Massachusetts Volunteers fighting their way through the streets of Baltimore, on their march to the defense of the National Capitol on the 19th of April 19th 1861. Hurrah for the Glorious 6th.”

The Civil War’s First Bloodshed

18 April 1861

A Day Before the Pratt Street Riots was a Different Set of Fighting and Rioting - Down Howard to Camden, up Camden to Eutaw, Paca and Pratt streets to Mount Clare Depot Setting the Stage for What Would Come the Next Day at Pratt and President Streets

On April 18, 1861, two companies of US Artillery and four companies of militia arrived from Harrisburg at the Bolton Station, in the northern part of Baltimore. A large crowd assembled at the station, subjecting the militia to abuse and threats. According to the mayor at the time, “An attack would certainly have been made but for the vigilance and determination of the police, under the command of Marshal Kane.”

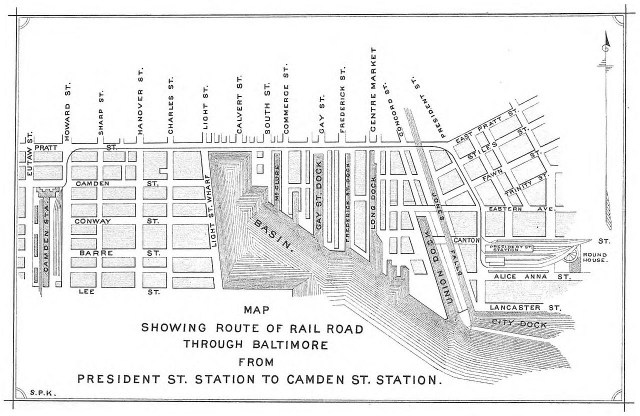

Kane and others in Baltimore, knowing the fever pitch of the city, sought to learn about plans for other troops to pass through town, but their telegrams north asking for information were largely ignored, probably at least partly because of Kane's well-known Southern sympathies. So it was on the next day, April 19, that Baltimore authorities had no warning that troops were arriving from Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. The first of the troops had arrived at the President Street Station, on the east side of town, and had successfully traveled the one-mile distance along East Pratt Street via horse-drawn rail cars, to the Camden Street Station (now near modern "Camden Yards"/Oriole Park baseball stadium) the west side, to continue to Washington. There a disturbance ensued that soon brought the attention of Marshal Kane. His police, (according to Mayor Brown's later memoirs), prevented a large and angry crowd “from committing any serious breach of the peace.” Upon hearing reports that the mobs would attempt to tear up the rails leading toward Washington, Kane dispatched some of his men to protect the tracks.

Meanwhile, the balance of northern troops encountered greater difficulty traversing Pratt Street. Obstructions were placed on the tracks by the crowd and some cars were forced back toward the President Street station. The soldiers attempted to march the distance along Pratt Street, and according to Mayor Brown was met with “shouts and stones, and I think an occasional pistol shot.”

The soldiers fired back, and the scene was one of general mayhem. Marshall Kane soon appeared with a group of policemen from the direction of the Camden Street Station, “and throwing themselves in the rear of the troops, they formed a line in front of the mob, and with drawn revolvers kept it back. … Marshal Kane’s voice shouted, “Keep back, men, or I shoot!” This movement, which I saw myself, was gallantly executed and was perfectly successful. Said, Mayor Brown. “The mob recoiled like water from a rock.” By the time it was over, four soldiers and twelve civilians were dead. These were the first casualties of the American Civil War and they occurred on 19 April 1861.

Even though Kane appears to have executed his duties faithfully during these events, and wrote an official account defending his actions (Public record defense by Marshall George P. Kane of his actions on April 19, 1861, in dealing with the riot in Baltimore that "shed the first blood of the Civil War," there is no question that he was very pronounced in his Southern sympathies. After the riot, Marshal Kane telegraphed to Bradley T. Johnson in Frederick, Md. as follows:

"Streets red with Maryland blood; send expresses over the mountains of Maryland and Virginia for the riflemen to come without delay. Fresh hordes will be down on us tomorrow. We will fight them and whip them or die."

This startling telegram produced immediate results. Mr. Johnson, afterward served as a general in the Confederate States Army, commanding the Maryland regiments came with volunteers from Frederick by a special train that night and other county military organizations began to arrive. Virginians were reported hastening to Baltimore.

Nicholas Biddle and the First Defenders CLICK HERE

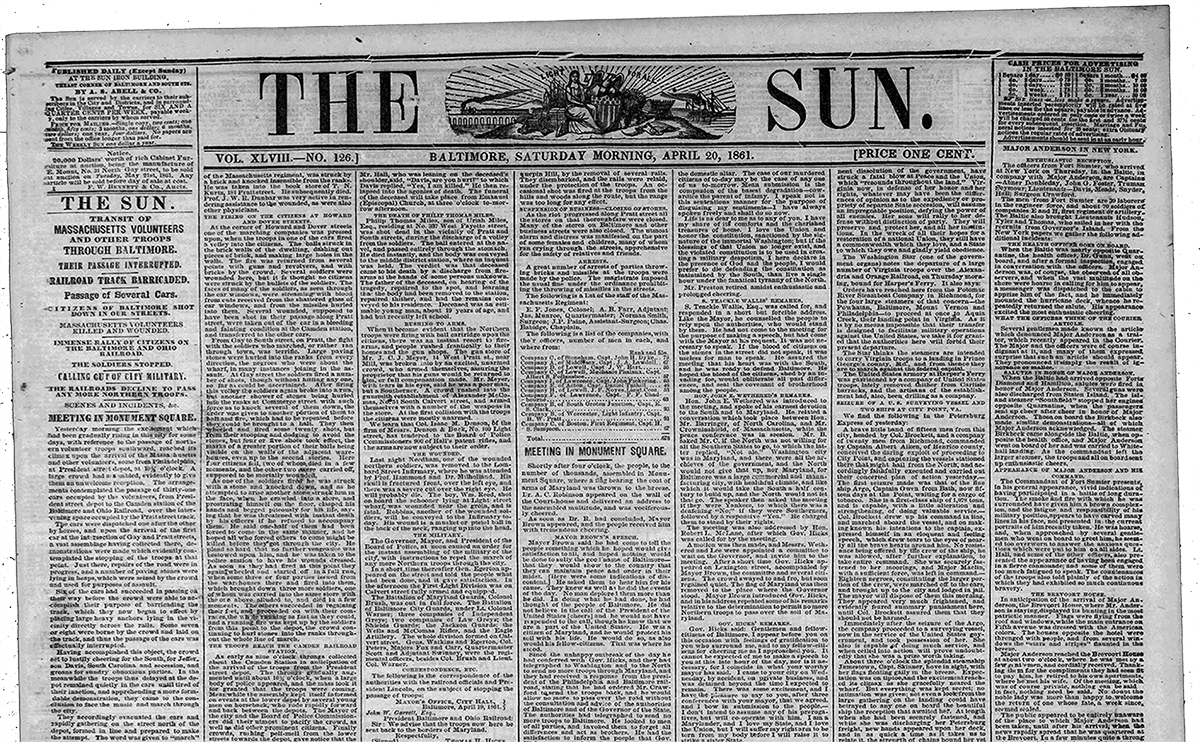

Newspaper Articles About the Two Riots 18 April and 19 April 1861

Newspaper Articles About the Two Riots 18 April and 19 April 1861

19 April 1861 Pratt_and_President_street

The_Baltimore_Sun_Fri_19_April_1861_Howard-St-Riots

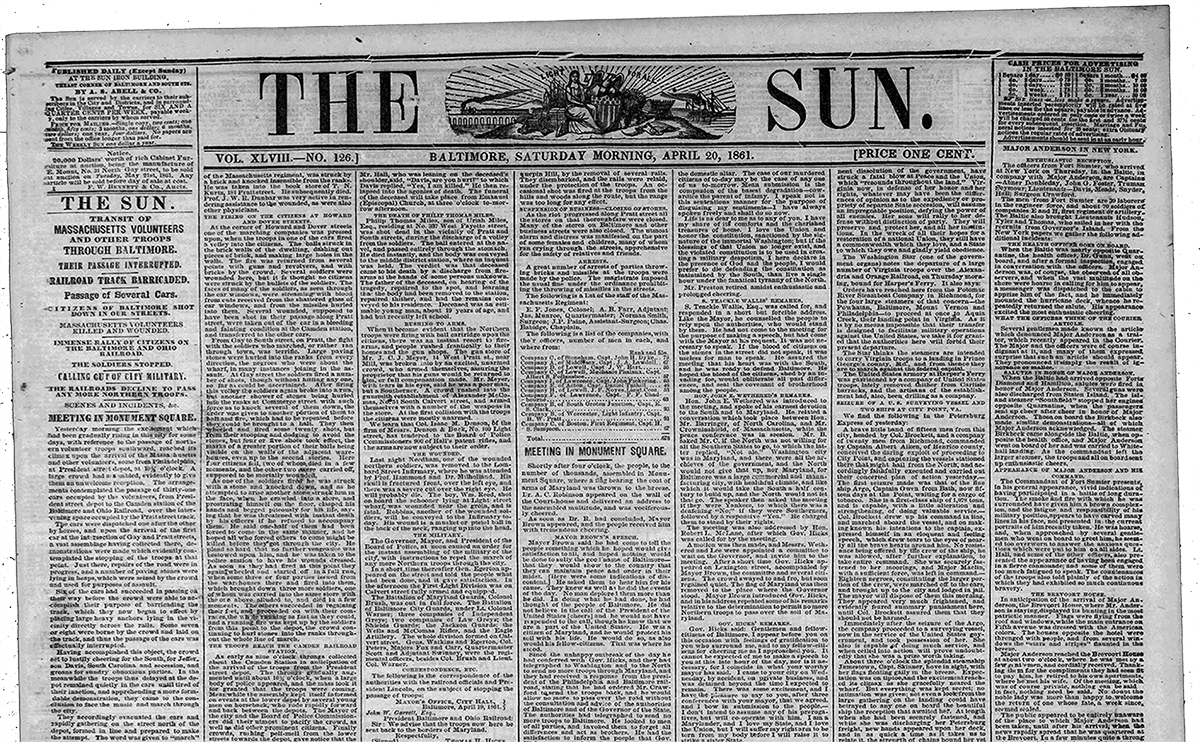

The_Baltimore_Sun_Sat_20_Apr_1861_pg1

The_Baltimore_Sun_Sat_20_Apr_1861_pg2

CIVIL_WAR_22_April_1861

THE_EXCITEMENT_IN_BALTIMORE_25_Apr_1861

There are many things in history that no one today can change, but that have over the years seen changes and many improvements for the better. It is true that at one time Baltimore police officers, or Patrolman to be more precise were given orders to chase and arrest slaves, this was long before todays Baltimore Police Department, and in fact today’s Baltimore Police Department is not the same Baltimore Police Department in more ways than the obvious. If we were to shut down todays department and start a new department tomorrow in this city for obvious reasons it would be called Baltimore City Police Department. Truth of the matter is, todays Baltimore City Police Department has never made an arrest for slaves, the Baltimore Police Department that made slave arrests ended on 27 June, 1861 when new police commissioners were appointed by the U.S. Military authorities under direction of then president Abraham Lincoln as the former BOC (Board Of Commissioners) was replaced with Columbus O'Donnell, Archibald Sterling Jr., Thomas Kelso, John R Kelso, John W Randolph, Peter Sauerwein, John B Seidenstricker, Joseph Roberts, and Michael Warner. All police prior to 27 June 1861 were dismissed from the police force and had to reapply with only the best of the former police being rehired and many left go for good. One might also be interested in knowing at the time Baltimore was not as big as it is today and the city had less than 400 police officers closer to 320 maybe 350. During the next year between June of 1861 and March 1862, the streets were protected by military police. On 29 March 1862 our newly sworn police officers stepped in, wearing a new uniform, a new badge with a new police authority, new rules, under new laws, and no longer were they making slave arrests. The time between 27 June 1861 and 29 March 1862 the replacement temporary fill in law enforcement wore plain clothes, and were only recognized by a simple, "Pink Ribbon" worn on their left lapel, along with an, "Espantoon" carried for the public and, their protection. Other than those two identifiers, a uniform for the newly built Baltimore Police Department had not yet been selected, and so until it was, they dressed in civilian attire.

The reason for the change was largely due to not just Marshal Kane, and the BOC at the time, but also because of Mayor Brown. Many believe after the riots on 18 April 1861 on Howard street where Baltimore civilians attacked U.S. Military on its way to Washington DC in preparation of the civil war. Mayor Brown and Marshal Kane hatched a plan for a second attack to take place a day later on 19 April 1861 at Pratt and President streets. There are said to have been telegraphs sent from Kane to his confederate army allies telling them where and when to attack the 6th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, a volunteer militia, who passed from the President Street Station 1.1 miles west at Camden Station, (now Camden Yards) while they were in route to Washington D.C. It is awfully odd that one day after the Howard Street riots, Marshal Kane would have some of his men across town, and others stationed at the end of the soldiers’ route and not at the beginning where they knew the soldiers would be departing the trains coming in from the north before transferring to another set of trains to take them into Washington DC. But the fact is, Marshal George Proctor Kane was arrested, he was found to have been funneling police ammo, weapons and equipment to the Confederate Army. Kane was first taken to Fort McHenry, but at the request of the commander of Fort McHenry, Kane was moved to Ft Warren, Massachusetts. His position as Marshal of Police, and his southern sympathies were well known, and a large part as to why the department was disbanded during that June of 1861 and rebuilt to a new department, in March of the following year. And there we have it, Baltimore City Police Department became a new department with new uniforms, new men, and as that new agency it has never made slavery arrests. It should also be known that in the nearly 160 years since it has changed many times over.

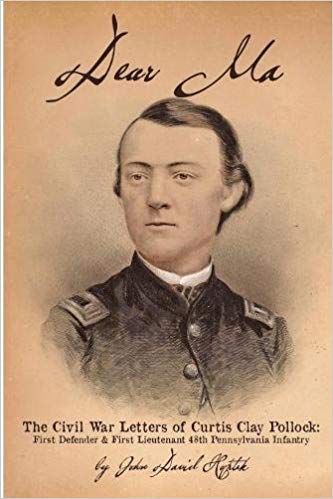

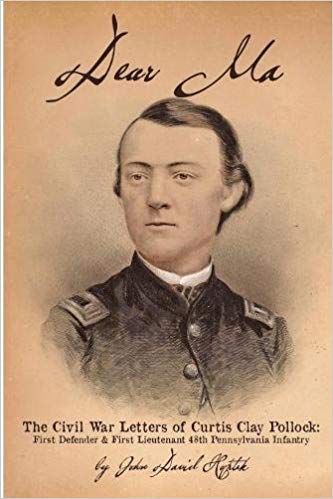

From the book,

Dear Ma – The Civil War Letters of Curtis Clay Pollock - First Defenders and First Lieutenant of the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry by John David Hoptak

Curtis Clay Pollock was one of among the more than two million soldiers who donned a Union blue and fought in defense of the United States during the American Civil War. And, by war’s end, he would be counted among the many hundreds of thousands of those soldiers who died to help ensure that this nation might live.

He was among the very first to respond to his countries call, volunteering his service immediately upon the outbreak of hostilities in the spring of 1861. On 17 April of that fateful year, just five days as the wars opening at Ft Sumter and in response to President Abraham Lincoln’s first call to arms, 18-year-old Curtis Pollock marched off to war as a private in the Washington Artillery, a militia company recruited from the young volunteer’s hometown of Pottsville, Pennsylvania.

The very next evening (18 April 1861), the Washington Artillery, along with four other companies of Pennsylvania volunteers, arrived in the distressed Nation’s Capital. As it turned out, these men, Pollock included, would be the very first Northern Volunteers to arrive in Washington following the commencement of the war and would go down in history as the famed "First Defenders." As earlier that same day (18 April 1861) as the volunteer soldiers of these five companies made their way through the streets of Baltimore on their journey south to Washington, they were assaulted by a vehement mob of Pro-Confederate sympathizers who hurled not only insults, but also bricks, bottles, and stones. Pollock escaped injury, but some of the Pennsylvanians were struck down and seriously injured during the melee, thereby shedding some of the very first blood in what would prove to be America’s bloodiest war.

This serves as more written documentation of the first day of fighting in Baltimore's two days of rioting in our streets. This first day on the 18th led to the first bloodshed of the civil war, the next day the 19th led to the first deaths of the civil war.

The Civil War’s First Dead

19 April 1861

There Were the 12 Baltimoreans Killed in the Bloodied Pratt Street Riots

The most significant Civil War action in Baltimore was the Pratt Street Riots of Friday, 19 April 1861, which directly caused 17 known deaths, at least 50 injuries and 7 recorded the arrest.

Most of the fighting took place along President Street, from near the harbor north to Pratt Street, and along Pratt St., west to Light Street. The violent action would last from approximately 11 AM to 12:45 PM and most involved 220 New England Militiamen, some of whom carried and fired muskets, and a mob of Baltimore civilians including a few Maryland Militiamen that were out of uniform and were reported to number anywhere from the 250 that initially arrived to as many as 10,000 and who had fired a few pistols but fought mainly by grappling with passing Militiamen or by hurling paving stones.

Of the 600 or so officers and men of the 6th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, Volunteer Militia, who passed from the President Street Station 1.1 miles west to the Camden Station, in route to Washington, four were killed and about 35 wounded. The dead soldiers, all of which were enlisted rank, were Addison O. Whitney, Luther C. Ladd, Charles A. Taylor and Summer A. Needham. The last named died with “little resistance” in a Baltimore hospital about a week after the riots and during the 19th-century style operations on his fractured skull.

Of the 1000 unarmed Pennsylvania Militiamen and about 100 additional members of the 6th Massachusetts, including the Regimental Band, who arrived at the same time, none made it through the mob around President Street Station on their journey, and only one died of injuries sustained. His name was George Leisenring, and he succumbed to his injuries about a week later after he returned to Philadelphia.

Many Baltimoreans were wounded, and 12 were killed – James Clark, William R. Clark, Robert W. Davis, Sebastian Gill, Patrick Griffith, John McCann, John McMahon, Francis Maloney, William Maloney, Philip S. Miles, Michael Murphy and William Reid.

At the time, and off and on ever since, many Baltimoreans were most outraged by the death of Mr. Robert Davis, a 36-year-old dry goods merchant & innocent bystander that may have cheered for the Confederacy, but did not join in the fighting. Mr. Davis was shot by someone on the 6th Massachusetts train shortly after it pulled out of Camden Station. Upon being hit by the round he was heard to cry out, “I am killed!” as he fell, and the next day a Baltimore Coroner's jury decided that he had been “ruthlessly murdered, by one of the militaries.” Mr. Davis’s funeral was elaborate, but his murderer was never named, charged, or prosecuted.

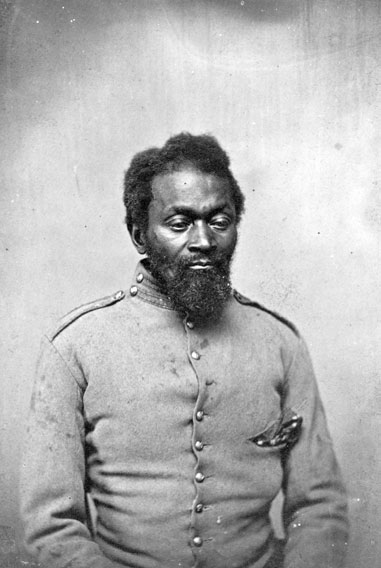

Two of the dead civilians, Patrick Griffith and William Reid, both young black men that had been employed in the area. Patrick Griffith was employed on one of the oyster slopes that was tied up on the docks near Pratt and Light Streets. William Reid was employed by a Pratt Street establishment described only as the “Greenhouse” and was “shot through the bowels while looking from a doorway on Pratt Street.”

The ages, addresses, occupations, specific circumstances of death and last rites of the other Baltimore casualties have apparently never been recorded, although those who fell in the Pratt Street Riots turned out to be the first fatality victims of a hostile action in the Civil War (no one was killed during the action which it ended four days earlier at Fort Sumter. South Carolina.)

The most thorough contemporary accounts of the Riots, and Baltimore newspapers, state that the police arrested “great numbers” afterward. Only seven were apparently ever named anywhere – Those were, Mark Kagan and Andrew Eisenbrecht, charged with “assaulting an officer with a brick,” Richard Brown and Patrick Collins, “throwing bricks, creating or contributing to a riot” William Reid, “severely injuring a man with a brick” J. Friedenwald, “assaulting an unknown man,” and Lawrence T. Erwin, “throwing a brick on Pratt Street.”

These Seven Constitute Another Civil War “First.”

The Troops for Massachusetts and Pennsylvania responding to Abraham Lincoln’s 15 April 1861 call for volunteers, and many Baltimoreans in slave-holding Maryland interpreted that to be an effort to recruit an army to invade such seceding “sister states” as Virginia. A Confederate Army recruiting office flourished at Marsh Market: a process session mob of about 800 had roamed Charles Street on the night before [18 April] and more than one African American had been flogged for cheering the Republican President in public.

So the Baltimoreans in the Pratt Street Riots were as much Pro-Southern as they were simply Pro-Maryland or simply outraged by the alleged violation of state sovereignty by another state's militia (an idea suggested in “Maryland! My Maryland! The official state song that was inspired by and written shortly after the Riots by Ryder Randel, a native Baltimore English teacher who at the time was living in New Orleans).

And so the seven Baltimoreans arrested turned out to be the first Civil War partisans of either side who suffered official legal action for their pains. Of them, only one, Lawrence T. Erwin was convicted and “held for a sentence” so far as contemporary accounts, historians and memoirs reveal. His sentence, if any, was unrecorded.

One History of the Baltimore Police Department

One history of the Baltimore Police Department explains that “It was useless to arrest men when not one officer could be spared to put them in jail.” It seems, too, that although the department had been reorganized about a year earlier under Marshal George P. Kane to rid it of corrupt “Know Nothing” political elements, it had no patrol wagons in 1861. Patrol wagon wouldn't come to Baltimore until 1885] And since the main body of the police detailed to maintain order during the malicious passage was about a mile away at Camden Station, or in route to the scene of the fighting during most of the rioting, it is perhaps remarkable that as many as seven arrests could be made.

Why the main body of police was at the end of the troop's projected route, instead of at its beginning, is still something of a mystery. The recollection of the riots that were published nearly 20 years after the event by George William Brown; [Mr. Brown was the Mayor of Baltimore during the riots in 1861] He lays part of the blame on the management of the P. W. & B. Railroad. The company failed to answer Marshall Kane’s repeated telegrams that asked how many troops were in route to the President Street Station and when they would be expected to arrive. So, by 10:30 AM on the morning of 19 April 1861, the police could do nothing better than send their main body – “a strong force” – to Camden Station. Such action was proper, explained the former Mayor, even though large crowds had assembled at both stations as early as 9 AM and even though the Secessionist Flag – [a circle of eight white stars on a field of blue] – was displayed by the throng at President Street Station.

Passengers who arrived from the north on the PW & B. Then customarily stayed on the cars at President Street if they were bound for Washington, and the cars were hauled one by one, by horse teams of four, to Camden Station, where the passengers got off the PW & B cars and boarded the B&O railroad cars before continuing on to the National Capital. “As the change of cars occurred at this point,” a Police Department history published in 1888 remarked, “It was here that the greatest risk of attack was feared.”

But why at Camden Station, to which the troops would have been pulled more than a mile through angry spectators who had already been hurrahing Jefferson Davis, President of the New Confederacy, and jeering President Abraham Lincoln for an hour and a half?

Only the day before, a lesser Riot resulting in no deaths, began near the Bolton Station when another troop of Pennsylvania Militia (the 1st Defenders) de-trained in North Baltimore and was stoned by a mob as it marched south to board a train for Washington. The police supplied more or less effective protection for the 1st Defenders while they were afoot in Baltimore on that day [18 April 1861]. Why then did Marshall Kane apparently reversed his strategy on 19 April 1861 when he decided that the 6th Massachusetts et al, would be safe while on the cars as they were pulled from the President Street Station to Camden Station.

Mayor Brown later decided (in his memoirs of the riot, published in 1887) that the 6th Massachusetts et al would have been more imposing, therefore safer, if they had marched as a body of 1700 men from one station to the other. Just such an order for marching through Baltimore was apparently prepared by the 6th Massachusetts Commander, Colonel Edward F. Jones, but it was abandoned, “Someone had blundered,” Mayor Brown concluded, hinting strongly that someone was a PW & B executive.

The logic of hindsight suggests that the main – body of police should have met the train at President Street Station and that adequate details of officers should’ve escorted each of the horse-drawn cars of soldiers to the Camden Station. As it happened, the first nine cars of the 35 car troop train hauled Colonel. Jones and seven of his 11 Massachusetts companies of President Street, across Pratt Street and down Howard Street to Camden Station with little, if any, police escort – and still, they made the trip without any serious mishaps. The crowds hissed a little but were only able to throw stones at the last car, and Mayor Brown, who by this time had arrived at Camden Station from his law office, thought that maybe the nine cars were the all there would be.

The tenth car was halted at the Pratt Street bridge over Jones Falls by a wagon load of sand that the mob dumped in its path, some anchors (perhaps eight) that were dragged from nearby ships across the tracks by several African American seamen, and a motley barricade of lumber and paving stones that were handy because the streets by happenstance were under repair at that point.

The tenth car then turned around retreating toward the President Street Station, where the mob had swelled to roughly 2000 and where some police had arrived (from outlying districts, apparently: not from the main body of police at Camden Station) as the 220 or so soldiers de-trained and lined up in single file. Their effort to march to Camden Station became unlikely as formation were blocked by a lot of men flying the secession flag; so they reformed into a double file, did an about face and marched in the opposite direction, conceivably inspired to dive into the harbor and swim west toward Light Street.

The mob, having savagely choked a Union Sympathizer who had tried to tear down the Secession Flag, circled the soldiers and halted the de facto retreat. The troopers then fell in by platoons, four abreast, and, with police help, wedged a path north on President Street. The gang with the Secession Flag marched ahead of them and savagely beat two more union sympathizers who tried to tear down the banner, then ran among using militia ranks. Part of the crowd behind the 6th Massachusetts column then began to throw stones, one of which felled a trooper named William Patch, who was then beaten with his own musket.

The four companies – C, D, I., and L. – Then began either “to run” or march “at the double quick,” presumably on orders from one or all of their Captains, who were named Follansbee, Hart, Pickering, and Dike. Two more soldiers were knocked down at President and Stiles Streets – possibly by a iron or one of the “queer missiles” (a term used at the time to describe chamber pots) that were thrown by Baltimore women in the mob, according to the 1936 reminiscence of Aaron J. Fletcher, the last survivor of the Civil War 6th Massachusetts.

Mr. Fletcher’s is the only direct account that even suggest women were involved in the riots. (A romantic story, written in 1865, alleges that a Baltimore prostitute named, Ann Manley saved the 6th Massachusetts regimental band by guiding them away from the President Street Station by back alleys – but most accounts state that the police protected the musicians.)

B&O Railroad Stocks Dated 19 April 1861

We are trying to crop to the date 19 April 1861

At about the time the troops turned the corner into Pratt Street, at any rate, someone fired the first shot.

E. W. Beatty, of Baltimore, fired that shot from the crowd, according to an opinion that seems to be based on the opinions of Confederate Officers with whom he later served before he was killed in action. One of the 6th Massachusetts soldiers fired the first shot, according to contemporary newspapers accounts that attributed the information to a policeman identified only as “number 71.” By that time Mayor Brown had heard that a mob had torn up President Street using the cobblestone/brick as missiles and had quickly advanced to the bridge where he met the New Englanders and joined them in their March at the head of the column as far back toward Camden’s Station as Light Street.

Mayor Brown’s account states that he slowed the soldiers' pace (they also had to pick their way through the haphazard barricade at the bridge), that Captain Follansbee said: “We have been attacked without provocation,” and that he, Mayor Brown, replied: “You must defend yourselves.”

The troopers, of whom about 60 carried muskets, then began to fire in earnest – in volleys, according to the newspapers; over their shoulders and helter-skelter, according to Mayor Brown: definitely not in volleys, according to Aaron Fletcher’s recollection (although he was in Company E, which passed safely through in one of the nine cars).

The First Baltimorean Hit (in the groin) was Supposedly Francis X. Ward.

A Unionist newspaper in Washington quoted Colonel Jones the next day as saying that Mayor Brown had seized a musket and shot a man during the March. Mr. Brown later wrote that a boy he had handed him a smoking musket which a soldier had dropped and that he immediately handed it to a policeman.

The mayor must’ve found the Pratt Street riots quite embarrassing. Then 48 years old, he had been elected in October 1860, on a reform ticket dedicated to absolving Baltimore of its nickname, “Mobtown,” and had helped put down the Bank of Maryland riots in 1835. He believed in freeing the slaves gradually but felt that slavery was allowed by the Constitution and that the south should be allowed to secede in peace.

He was summarily arrested by the Federal Military in September – 1861, and imprisoned until November – 1862. From 1872 until the year before his death in 1890 he served as Chief Judge of the Supreme Bench of Baltimore City. He was defeated in a campaign for Mayor in 1885.

When Mayor Brown left the Massachusetts infantrymen, near Pratt and Light Streets, most of the casualties had fallen, the fighting having been heaviest near South Street. The Baltimore dead and wounded were mostly bystanders, according to most Baltimore accounts, because the running soldiers allegedly fired to the front and sides and not at the hostile mobs behind, which may have been as small as 250 men, according to the “ Tercentenary History of Maryland.”

A historian who took notable exception to the bystander the only version was J. Thomas Scharf, author of the “Chronicles of Baltimore,” which describes an “immense concourse of people,” that to a man threw paving stones at the troopers from in front of them.

Before the column Reached Charles St. Marshall Kane and about 40 of his police had finally arrived from Camden Station and threw a cordon around the soldiers. “Halt, men or I’ll shoot!” The Marshal is supposed to have cried as he and his men brandished their revolvers. The mob headed to the Marshal's warnings and halted their actions.

That evening Marshall Kane telegraphed friends to recruit Virginia rifleman to defend Baltimore from further invasion by Union Militia. In June, after Gen. Benjamin Butler “occupied” Baltimore with other Massachusetts troops, the police Marshall was also arrested and imprisoned. He was released in 1862, and “went to Richmond,” apparently by an informal agreement, and apparently served the Confederacy during the war. He died at the age of 58 in 1878, just seven months after he was elected Baltimore's 26th Mayor.

The 6th Massachusetts had left Baltimore by 1 PM on that 19th day of April 1861 – short of its dead and some of it's wounded, who were cared for in Baltimore hospitals or temporarily buried at Green Mount Cemetery, and it’s regimental bandsmen, who along with the 1000 unarmed Pennsylvania volunteers, were more effectively protected by the police from the two attacks at President Street Station by mobs which may have increased to as many as 10,000 persons from the initial 250, according to Mr. Scharf’s chronicle.

The Pratt Street Riots of 1861 occurred on the Anniversary of the Revolutionary War - Battle of Lexington, a coincidence which both Northern and Southern propagandist made a lot of, notably the former. The civic leaders of Baltimore called halfheartedly for a Law and Order in speeches in Monument Square on the same afternoon, ordered Railroad Bridges burned north of the city and persuaded President Lincoln to route further Washington defenders through Annapolis.

Much as the city might protest that its sovereignty had been violated, the rights appeared to the North to be a pro-Confederate outrage, and it is not difficult to understand why the Federal Government soon decided to clamp down on the city.

The 6th Massachusetts was in Baltimore three more times during the war its Survivors were honored here on several occasions afterward. It’s reception on April 19, 1861, caused far-reaching repercussions, though including the ironic turnabout in Baltimore which saw Unionist mobs roughing up succession us on the streets as soon after the riots as may, 1861

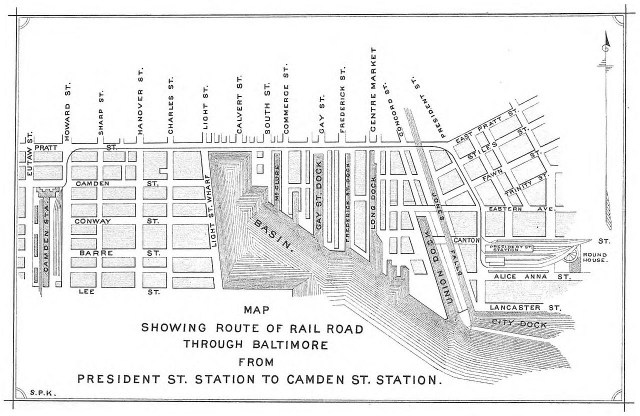

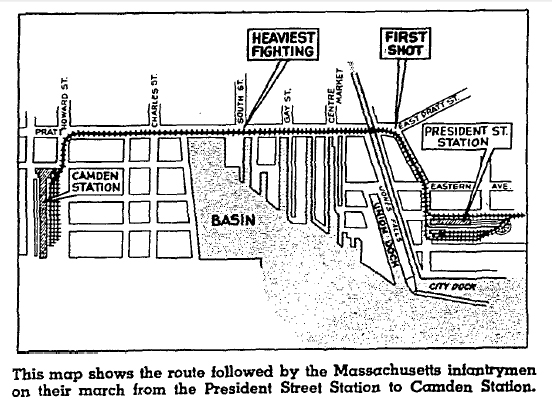

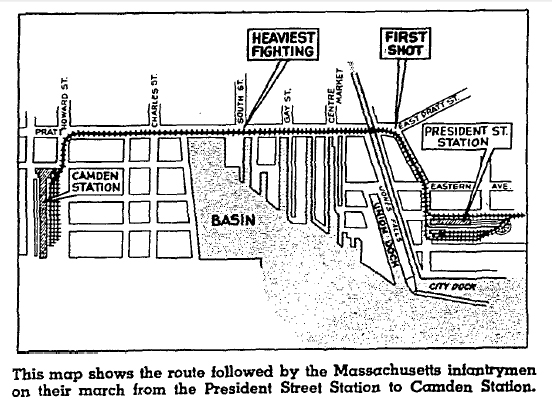

The above map shows the route followed by the 6th Massachusetts infantrymen on their march from the President Street Station to the Camden Station

The three contemporary drawings produced above show the six Massachusetts fighting its way along Pratt Street against the mob on 19 April 1861. The middle sketch is from Harper’s weekly the other two are from Frank Leslie’s pictorial history of the war.

The attack on the 6th Massachusetts was drawn by Albert Faulk Baltimore artist thought to have been a possible witness

Prohibiting the Display of Flags

29 April 1861

Prohibiting the display of flags – at this very critical juncture of opinions on bunting, the pulling down of an American flag by order of the board of police is an act which a little perverse ingenuity may distort into an atrocious, not to say flag-itious, offense.

If but can’t require good men to be true and responsible. We are not very sorry to find some disposition prevalent to deal unjustly and mischievously with this matter. We can say, with a knowledge of the facts, that our excellent board of police have done several things which none could regret the obvious propriety of doing more than they. Yet in all they have done, where is the man amongst us who will say he has suffered the provision of any civil right at their hands? Just think for a moment of the wonderful preservation of the general peace and order of the city through the fearfully exciting times of the last few weeks. Think how the turbulent elements of the city have been subdued. Think how few outrageous have a disturbed our sense of right and justice, when the inflamed populace were bent on securing arms by any means. Think of steady mild but effective restraint exercised over this whole community one passion and resentment steered the whole city to go forth and make war upon the Pennsylvania volunteers at Cockeysville, and a happy termination of that a fair in sending out to them an abundance of food to relieve their famished conditions. And think that this is the worst that can be said of that total Baltimore, with stay so lustily abuse in the north. That terry Norris, which, as it comes to its senses, will be induced to do us justice, while the south can really have no good cause of complaint against us.

But to the flag affair. Our citizens know very well that those whose taste for the display of flags is so exceedingly susceptible, enjoyed the opportunity of giving the national hunting to the breeze on Sumpter. – For several days’ sympathy with the administration and hospitality to the South was expressive in this way at several places in the city and at some newspaper offices. Then came the sad affair of Friday, the 19th, after which, and suddenly, the Confederate flag was in the ascendant, and the emblem of the Southern Confederacy was everywhere, while the national flag was voluntarily retired. But our readers are not aware that when a rush was made upon the quarters of the “Minute Men” to pull down the American flag, the first man who appeared to stop the lawless movement was Mr. Davis, one of the Board of Commissioners for the Baltimore Police, who at once resisted their purpose. The flag remained and was removed voluntarily and at leisure by the: “Minute Men” themselves, under the unpleasant feeling that it seemed to associate their sympathies with those who had shed the blood of our own citizens.

And a word here upon the Confederate flag demonstration. That was by no means what it has been supposed to be – a secession demonstration. It was an exhibition of that feeling which still pervades pretty nearly this entire community – an unwavering devotion to Southern Rights. And the mistake still prevails in the North, that the Union men of Baltimore are indifferent to Southern Rights: if this is not on egregious mistake, we have misunderstood our own citizens.

New BPD 1862

The Baltimore Police Department is disbanded, and rebuilt as a result of Marshal Kane, and Mayor Brown's handling of the Pratt St riots of 1861 HERE

The Baltimore Police Department is disbanded, and rebuilt as a result of Marshal Kane, and Mayor Brown's handling of the Pratt St riots of 1861 HERE

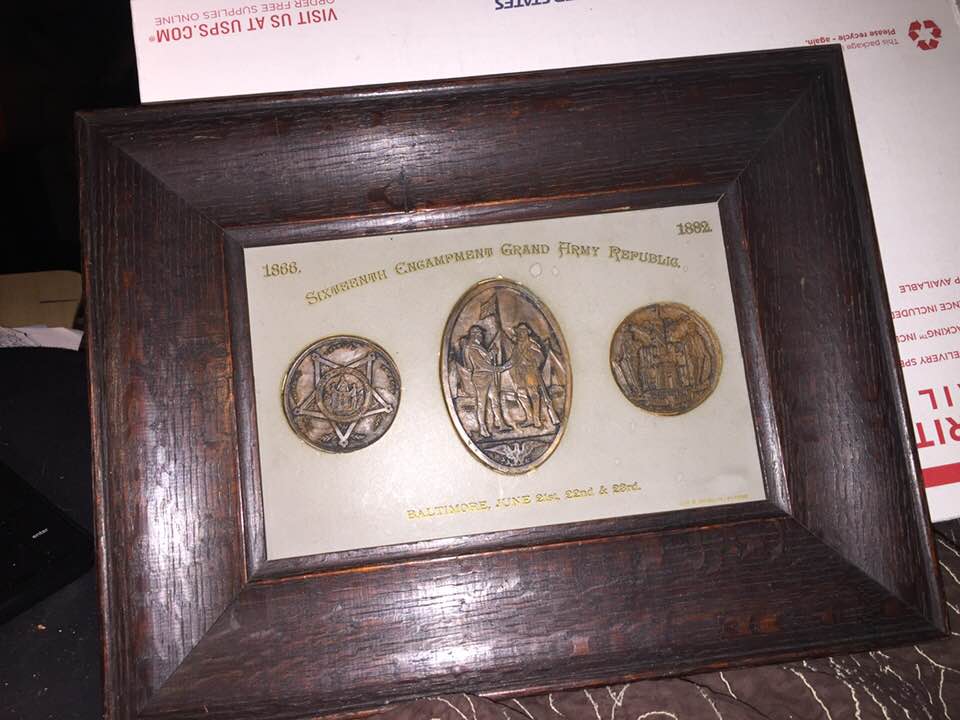

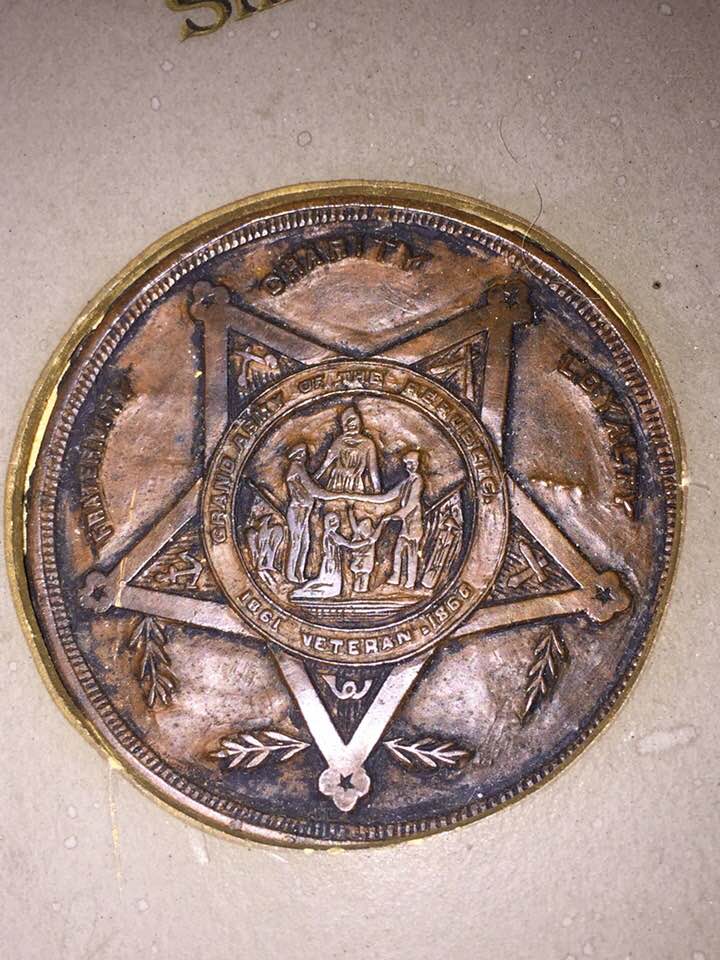

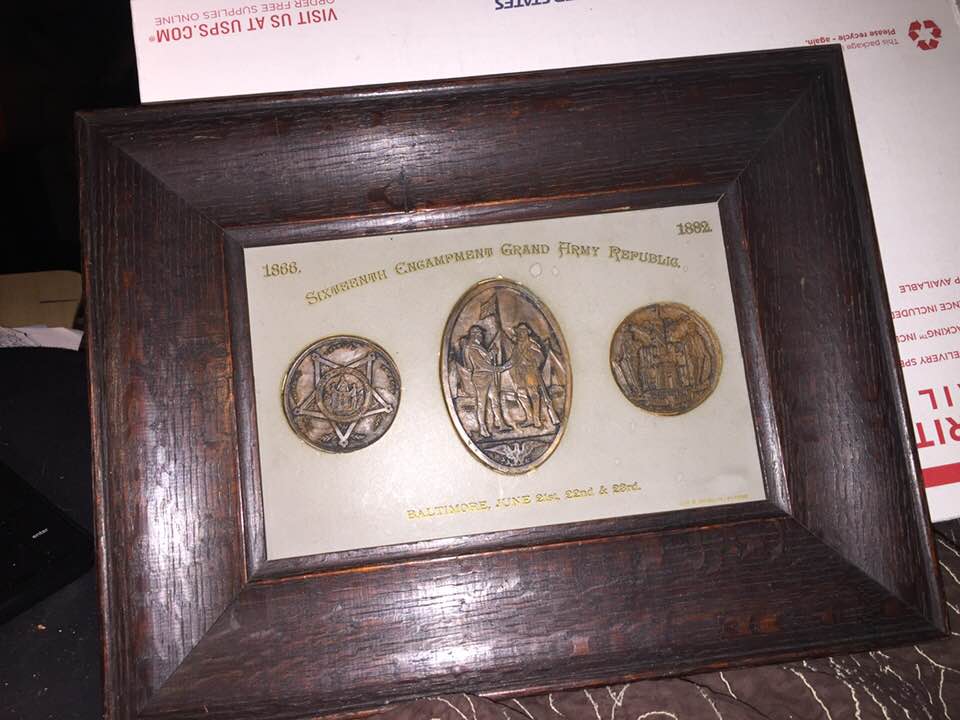

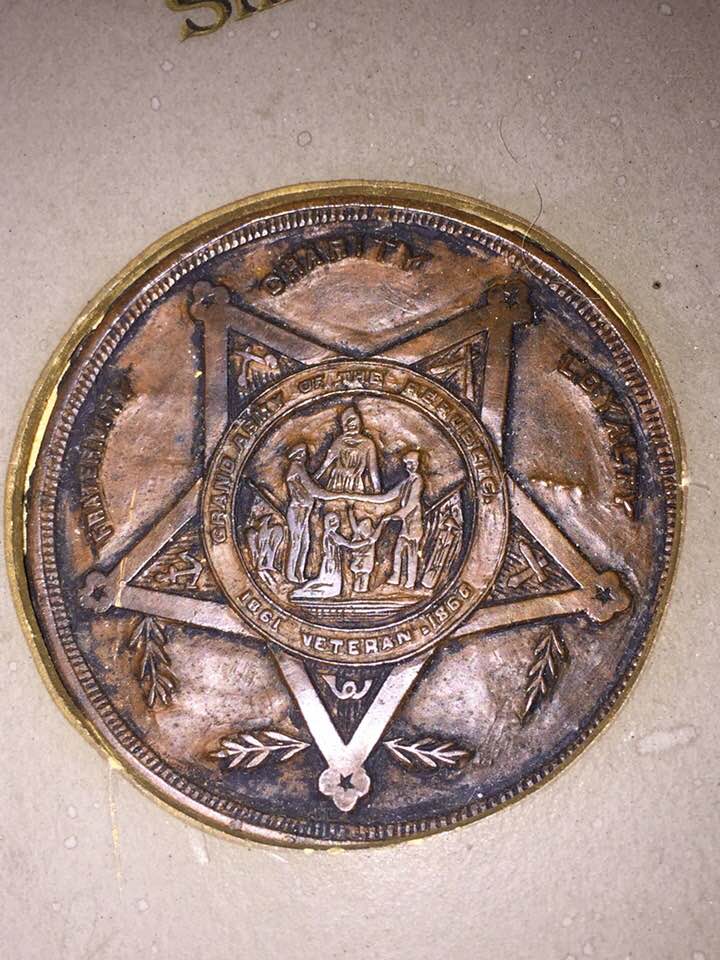

Civil War GAR Baltimore 1882 Encampment Set 3 Bronze Medals John G Mengel

RARE Medal set produced for the 16th GAR Encampment June 21,22,23 1882 in Baltimore Produced and signed lower right in the mat by John G. Mengel Jr.He owned a Type Set Company, quite famous of his own I have been selling historical Antiques for 32 here in Maryland, I have never seen this set before In original Printed mat and oak frame 13 X 10 overall Round medals 45mmOval center 74mm X 54mm

100 Years Ago

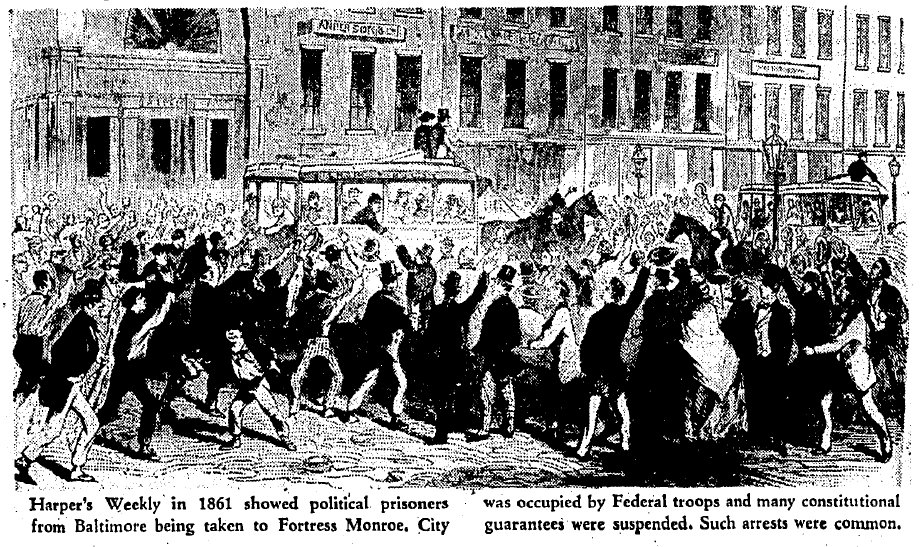

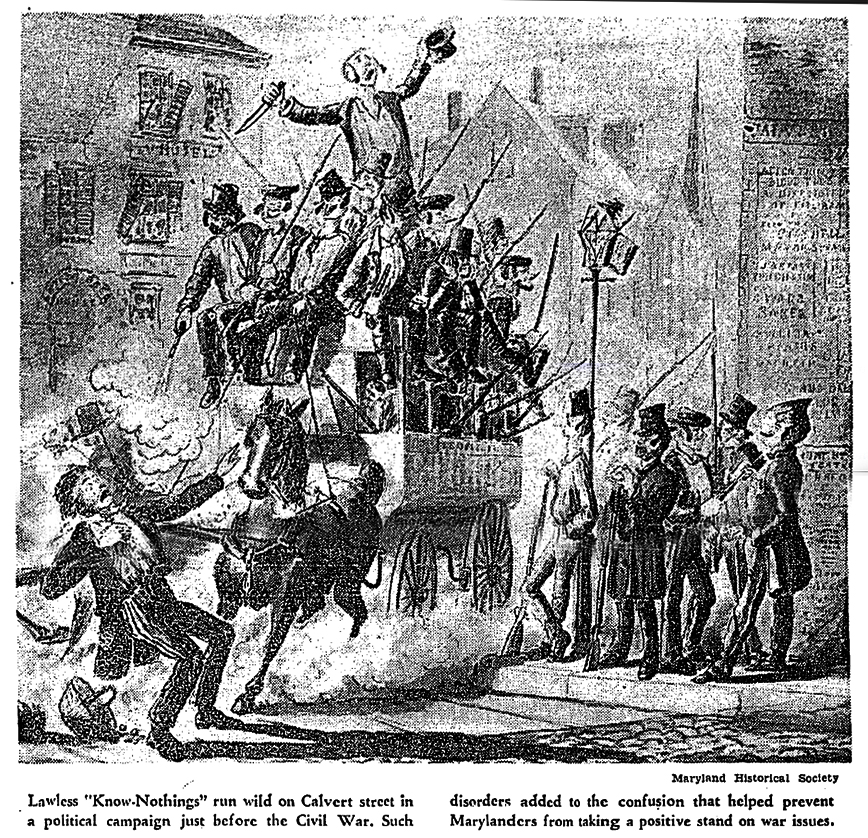

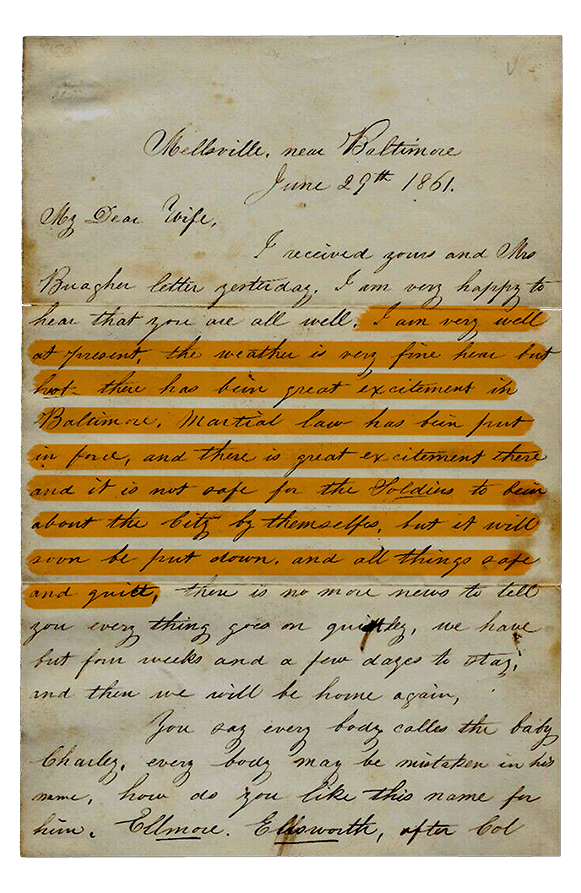

Why Marylanders Stayed “Loyal” To The Union

17 July 1960

MARYLANDERS

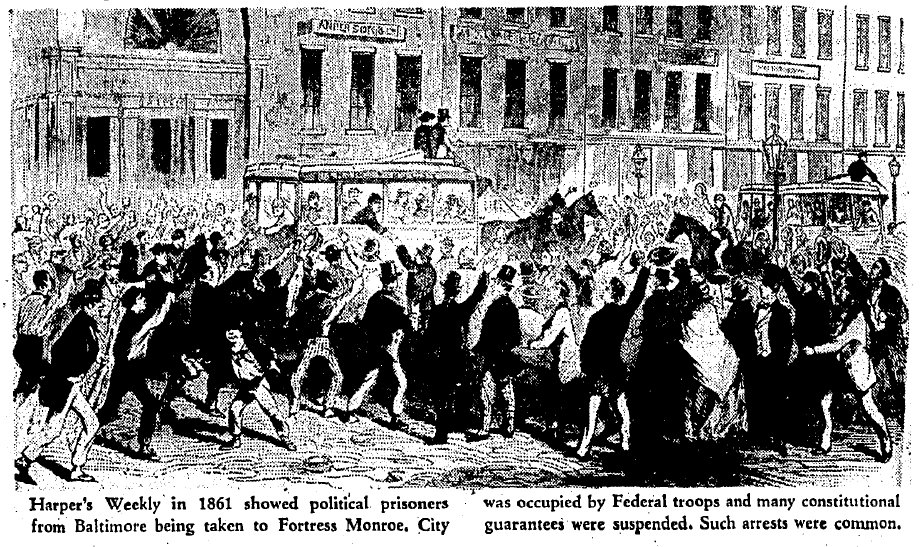

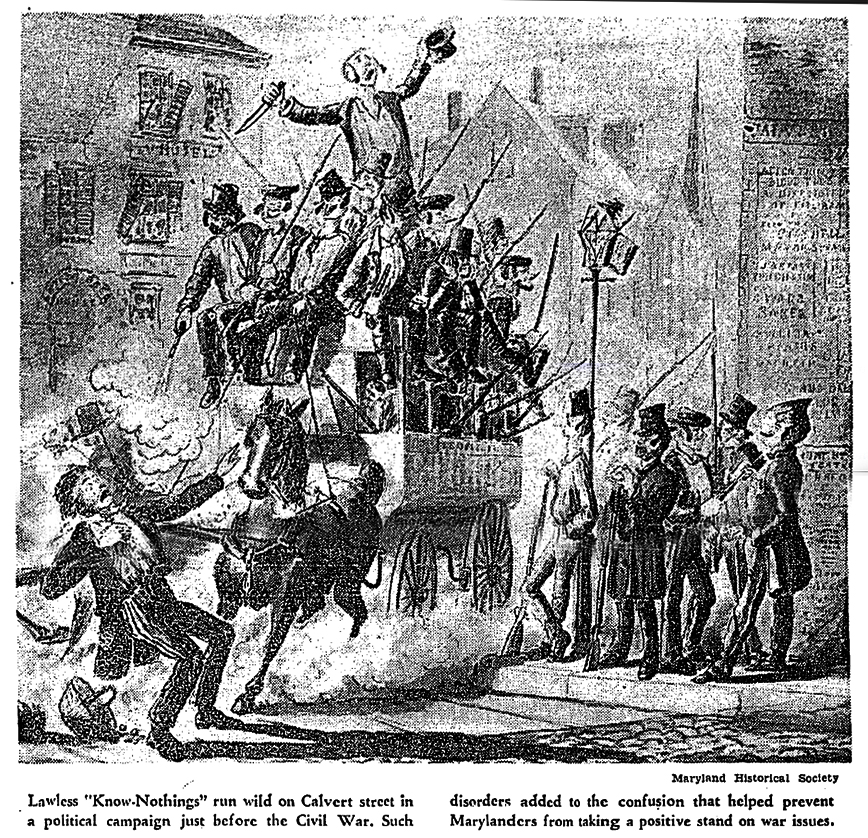

Who went to the polls 100 years ago this November to elect a President had four candidates to choose from. The campaign issues were as stark as union or secession; slavery or emancipation; alignment with the industrial North or the agricultural South; peace or war. The decade just past had seen lawlessness become routine in the streets as Baltimore’s infamous gangs - The Plug Uglies and Rip Raps, the Blood Tubs and Black Snakes - ran wild. It had seen reform efforts place the city's politically hobbled police powers in the hands of the State. Slavery had no great hold on Maryland, but the Dred Scott Decision. and violations of the fugitive slave law had inflamed large segments ·or the population. John Brown's raid the year before, conducted from Maryland soil, had brought violence close to the homes and hearts of all the State's residents.

Two-Way Pressure

As the wedge that split North and South drove deeper, increasing pressure was brought to bear on Maryland from both sides. Both looked to Maryland for the support they believed was vital in the further separation that appeared inevitable. Despite the agitation, however, Maryland took no unified stand; made no overt declaration of where her citizens stood on the issues of the day; did not even proclaim a position of neutrality between the disunited states. The reasons Maryland failed to speak out can be attributed largely to one man, Gov. Thomas Holiday Hicks. He was a controversial figure who had argued for a secession clause in the Constitution of 1851, spoken out for secession several times in the interim and made anti-Lincoln remarks. Yet he refused, time and again, to call a special session of the Legislature because he indicated he feared it would pass an act of secession. Hicks's course was neither brilliant nor consistent, but its outcome was that Maryland adhered to the Union-if not by choice then by failure to act until there was no alternative.

State Soil "Polluted"

The mixed motivation’s of Governor Hicks, the son of a Dorchester county farmer. characterized the pattern across the Stale. "Diversified" was the way a contemporary writer, W· Jefferson Buchanan, described Maryland's population. He said an influx of merchants, manufacturers and day laborers had "polluted" the State's soil, and blamed the resulting mixture for Maryland's failure to agree on Civil War issues. By 1860, there were almost as many free Negroes in the State as there were slaves: about 85,000. Slaves have been largely confined to the Southern counties and the Eastern Shore. In that year, almost one out of five free Marylander's had been born out of the State. Most of these were from foreign countries, but a sizable number-24,000- were from the North. There were 57,000 Germans, most of whom were Democrats of the Jeffersonian type,. espousing liberty and equality for all. These could not hold with a Democratic party that championed rights of slaveholders. On the other side of the political fence were the tobacco-raising families of English descent in the southern counties. These depended on slave labor, as did farmers of the Eastern Shore. Then as now, the small counties exercised a disproportionate influence in the Legislature; Baltimore in 1850 had one-fourth of the population but only one-tenth of the representation. The slave-holding counties were determined to uphold .this unbalance of power, fearful that a Legislature that more honestly represented the population would overthrow slavery.

United Front Impossible

A third major group was made up of commercial and manufacturing interests in Baltimore and the northern and western counties. Manufacturing did not use slave labor, and manufacturing in the 1850's had made great advances, while agriculture had remained 'relatively static. This group favored abolition of slavery but were less violent than the hardcore abolitionists. Commercial interests based their stand more on the material gains that would be forthcoming than on ethical principles. With these three forces pulling, as it were, in two-and-a-half directions, a united political front was impossible. The first big moment of decision for Governor Hicks came in December 1859, when South Carolina passed resolutions reaffirming its earlier claim to the right of secession and calling for a convention of all the slave holding states to devise proper defense measures and to consider the pros and cons of secession. The Maryland General Assembly referred the resolutions to a select committee. Governor Hicks himself was cool to the idea of secession.

Critical Of Abolitionists

The select committee made its report on March 8, and its tone reflected the repugnance with which most citizens at this time viewed a break-up of the Union. The report took cognizance of the "aggressive policy of the anti-slavery elements of the country towards our Southern institutions," condemned the system of assisting the escape of fugitive slaves and the "constant efforts of the Republican party of the North ... to trample still further upon our rights. Yet," the report continued. "Maryland will not be precipitate to initiate a system that may begin the destruction of this majestic work of our fathers." The fence-straddling stand continued with a declaration of the State 's intention to cast her lot with the South, should dissolution of the Union become inevitable. But it deemed a Southern convention inexpedient "'in the present excited condition of the country." It chose to rely for the time being on the hope 'that recent outrages had awakened Northerners to the dangers inherent in the situation. The National Democratic Convention of 1860 met at Charleston, S.C., on April 23. Three factions quickly emerged: supporters of Stephen A. Douglas, of Illinois, numbering half the 600 delegates: Colton Slates delegates who opposed Douglas and insisted on putting the slavery issue into the party platform; conservatives who opposed the extreme views of the Cotton States but who also opposed Douglas. The convention adjourned amid great confusion without agreeing on a candidate. It did agree to meet again in Baltimore on June 18.

A Row Over Seating

The city's hotels were filled as the opening session convened in the city's Front Street Theater. The new time and place failed to dispel the storm clouds that had hung over Charleston, however. There was an immediate controversy over sealing, in which Douglas men occupied seats of secession men. The convention again divided. Virginia withdrew first. followed by North Carolina, Oregon, and California. Kentucky and Tennessee retired for consultation. Georgia refused to re-enter the convention. Hopes for Democratic unity were completely shattered on the morning of June 23, when Caleb Cushing, president of the convention walked out along with a majority of the Massachusetts delegation. What was left of the convention then nominated the 48-year-old Douglas on two ballots. The balking delegates, along with those from Louisiana and Alabama, who had been refused admission, met that same day at the Maryland Institute. Twenty states were represented by partial or full delegations. In a harmonious session which lasted only a few hours, they nominated John C. Breckenridge. the 39·year-old vice president of the United States, for the presidency. This completed with a split in the Democratic party. In the meantime, however, members of still another faction had met a month earlier in Baltimore and nominated their candidate. The Constitutional Union Convention met at the old First Presbyterian Church al Fayette and North streets. It was made up mostly of "political antiquities:" members of the dying Know-Nothing party and old-line Whigs. They adopted no platform, except a windy declaration of principles of the Union the Constitution and the enforcement of laws. Sixty-three-year-old John Bell, of Tennessee, secretary of war under President Harrison, and a long-time political figure, was nominated for. the presidency. One week later, the Republican National Convention assembled in Chicago and nominated Abraham Lincoln as its standard hearer. Thus the four political armies drew battle lines for the November 6 election.

Lincoln Does Poorly

Polls opened in Baltimore at 8 A.M. and closed at 5 P.M. The city was suffering an economic depression as a result of the political unrest and various Government policies that were adversely affecting trade and production. Marylander's had no united political opinion to express, and by narrow margins, the electors of Breckenridge carried the city and State. The vote for him was 42,497; for his nearest competitor. Bell. 41,777. In electing Breckenridge, Marylander's aligned themselves - albeit weakly - with the deep South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana. Mississippi, North Carolina. South Carolina and Texas. Bell carried only three stales: Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia. Douglas voters in Maryland numbered 5,313: Lincoln supporters, 2,294. On the entire Eastern Shore. Lincoln polled only 25l votes. The total vote cast was more than 92,000.

Positive Stand Urged

After Lincoln's election, there arose a demand on the part of nearly all political factions that Governor !licks call the Legislature into special session, in order to establish some measure of control over the fast-developing and far-reaching events. The State's actions-or absence of them was being misinterpreted by both sides, and more and more Marylanders favored a positive stand, one way or another. In the South, the election of Breckenridge was hailed as a great victory. Hick's earlier cool replies to South Carolina on secession and other similar statements were held up in the North as evidence of Maryland's loyalty to the Union. From November to March, mass meetings were held frequently in Baltimore, some upholding the governor's course, others condemning it. Hicks, a square-jawed man with firmly set lips, was slow to reach decisions but tenacious in upholding them. His wavering course may have been partly prompted by fear, for his life was threatened numerous times. At the age of 63, he had a long history in politics behind him and apparently some enemies. He justified his course by assuming that the Legislature ~ which represented the State poorly - would adopt some revolutionary measure if called into special session. Nothing appeared safe, under this line of reasoning, except silence

Other Reasons Given

Historian J. Thomas Scharf gives other, more compelling reasons. "His views of national affairs were evidently influenced materially by his indisposition to act in concert with a political party in Maryland to which he was opposed. Old wounds were still rankling; unforgotten and unforgiven party defeats were still working in the executive mind, and he could look for no patriotic aid or counsel from the men who dared to curb the fraud and infamy by which he himself obtained his position." Thus, it was, Scharf concludes, that the expense of an unlimited Legislative session, private scheming, unwise legislation, and secession were the bugbears which prevented Maryland in this moment of impending revolution from taking a stand on the side of the South. Scharf himself was a Confederate veteran. Painful feeling in Maryland and the other border states were intensified on December 20 - six weeks after the election when South Carolina passed its ordinance of secession, breaking the stretched and weakened bonds of Union for the first time. Scharf reports that four-fifths of the people of Maryland regarded the course taken by the cotton states as rash and unwise. In January 1861. Governor Hicks stirred up more confusion by reporting a supposed plot by a secret Baltimore organization to seize the national capital, but he produced nothing to hack up his charges. A Congressional inquiry turned up information that one-time political clubs were turning into military-type organizations drilling-but found no evidence of plans to attack Washington. The reports only heightened the Federal Government's concern over the course Maryland might take. On February 11, President-elect Lincoln left his home for Washington and his inauguration. He was to have passed through Baltimore on a special train from Harrisburg on February 23, but instead, he quietly left his wife and the official party in Harrisburg early on the preceding evening and slipped through Baltimore in the night aboard a heavily guarded train.

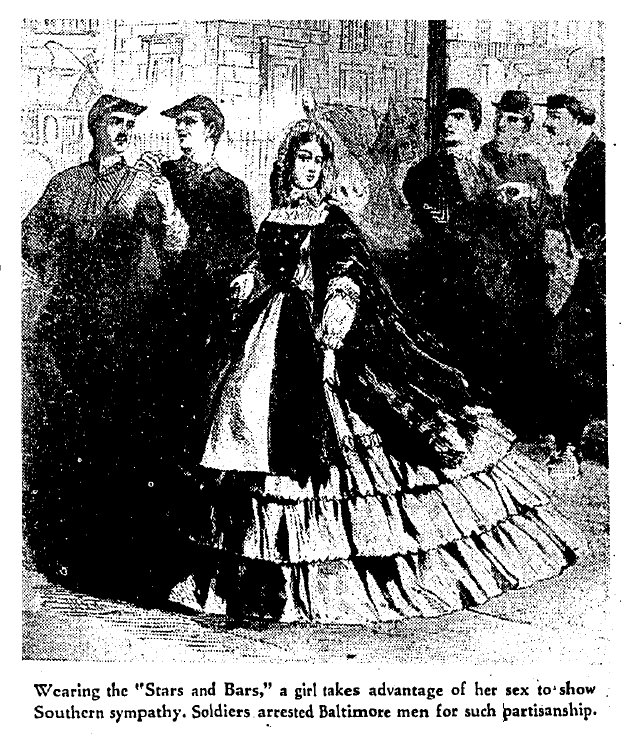

Stigma On The State

Much controversy surrounds the reasons for this. The popular explanation was that a plot to assassinate Lincoln as he passed through Baltimore had been uncovered. There was never any evidence produced of such a conspiracy, but the report circulated widely. Another opinion holds that Lincoln made the trip in secret to avoid meeting the Baltimore Committee to welcome him, whose members were unpopular in the State. Whatever the reason. the event had an unfavorable effect in placing a stigma on the people of Maryland in the eyes of the North and the Federal Government. A lull in the political storm settled briefly when Lincoln appointed a Marylander, Montgomery Blair, as his Postmaster General. But the bubble burst once and for all early on the morning of April 12 when Confederate batteries opened fire on the Federal garrison at Fort Sumpter in Charleston harbor. Three days later, President Lincoln. issued a call of 75,000 men to arms, ending all hopes of peace. If events up to this point had swirled crazily, now they exploded. Union and secession men spoke openly in the streets of Baltimore. Neighboring Virginia seceded two days after the call to arms. Two Confederate flags were hoisted on downtown buildings. Mayor George William Brown urged all citizens to refrain from acts that might lead to violence. A draft quota of 3,000 men was set for Maryland for l\lay. About 600 Federal troops from Pennsylvania marched through Baltimore and were jeered and pelted by crowds singing "Dixie's Land."

Rioting In Pratt Street

April 19 brought news of a bridge blowup at Harpers Ferry and of the approach of more troops from the North. That afternoon an estimated 10,000 citizens rioted in the streets in protest to the passing through of Federal soldiers. This bloodshed on Pratt street cast the die for Federal intervention into Maryland life and politics that lasted throughout the war. A committee of Baltimoreans was chosen to see President Lincoln and make a pica that no more Union soldiers pass through the "city. This was agreed upon, but the Federal capital considered itself in great danger. It was without communication with the North from the time of the Baltimore riot. Its communication via the Potomac was threatened and the arsenal at Harpers Ferry was in rebel hands. Avoiding Baltimore, a large Northern force under Brig. Gen. B. F. Butler boarded a ferry al Perryman and landed at Annapolis on April 23. To prevent Southern sympathizers from reinforcing and supplying the Confederates at Harpers Ferry, General Butler took a body of men and seized the Relay· House 6 miles from Baltimore on the B.& 0. Railroad. Then, under cover of a driving thunderstorm on May 13, he brought a large portion of his force into Baltimore and took possession of Federal Hill. He acted without orders and the storm ·kept citizens in their homes. From that time until the end of the war, Baltimore was an occupied city in every sense. Federal guns looked down menacingly and martial law prevailed Over political liberties and many constitutional freedoms. Two days after the Pratt Street riots, Governor Hicks did what partisans had been urging him to do for months. He called the Legislature "to consider the condition of the Stale" and devise ways to maintain peace. Since Annapolis was occupied by Federal troops, the Legislature convened at Frederick.

Only A Few Muskets

Legislators were bent on vindicating the rights o[ the. South and protecting Maryland's honor. They authorized Baltimore to raise $500,000 for its own defense and exonerated city officials of any blame in the April 19 riots. But beyond these measures, the Legislature was relatively powerless. The State's militia was scant. inexperienced and untrained. There were only a few muskets and no cannon. Virginia's preparedness was equally feeble and that Stale could have offered Maryland little help. Lincoln, on the other hand, could have bought 50,000 troops down if he encountered resistance. The Government was master of the Chesapeake and all navigable rivers. It had a strong garrison at Fort McHenry, troops on Federal Hill, a firm grip on Annapolis and control over the main rail link to the West. On the second day of its Frederick session, the Senate concluded that it had no Constitutional authority to pass secession legislation. The House of Delegates followed suit a few days later. This action was a bitter disappointment to the Southern counties and other secessionists, but the legislators resisted clamors of those who sought to break away from the Union.

More Trouble Provoked

Again. however. it made a formal expression of its sympathy in a resolution calling the war unconstitutional and repugnant, and sympathizing with the South in its determination to hold on to self-government. It sent a delegation to Jefferson Davis to assure him of Maryland's sympathy. Administration partisans in Ba1timore sought to provoke trouble by accusing the city administration of arming states rights supporters and working to plunge Maryland into revolution. Even though unfounded, these rumors were heeded by the Federal Government, which already had ringed the city with guns and troops. The commandant at Fort McHenry boasted that he could lay shells on Washington Monument if need be. On June 21, military authorities charged the presence of organized resistance to Federal laws in Baltimore and arrested Police Marshal George P. Kane, A provost marshal was appointed to head the city's police. Sharing Kane's fates were Mayor Brown and Ross Winans, a pro-Southern member of the Legislature and a nominee to Congress. The writ of habeas corpus was arbitrarily suspended by military authorities, and the suppression of newspapers was begun. Other arrests took place as the summer of 1861 wore on. Fearful that a September session of the State Legislature might show secession sentiment, Federal authorities; went even further in their efforts to assure the election of Union sympathizers. The Secretary of War ordered the arrest of' any members of the legislative body as well as other citizens the military authorities deemed necessary to prevent an act of secession. Fort McHenry became filled with political prisoners, and many of the Slate's leading citizens went South to join the Confederate forces.

Union Voters Guarded

The election of 1 November 1861, was the last test of strength between Unionists and states rights supporters. The State was to elect a governor, senators from eleven counties, as well as a large number of delegates and lesser officers. On election day, military rules were issued for the detection and apprehension of persons attempting to vote who were known to have aided the Confederate cause. Detachments of soldiers were sent to ''protect" Union voters, and these same soldiers were permitted to vote, swelling the Union margin. Many civilian voters were challenged, and some arrested. The vote was light, but the Union majority heavy. The Union ticket, headed by Augustus W. Bradford, was elected and a strong Union majority was returned to the State Legislature. Unionists continued to rule the Legislature until Federal military control was withdrawn from the State after the war. Maryland was a loyal state in fact, as well as in name, once Federal force had made certain it would follow such an oath.

Reader Notes

Courtesy Patrick W Dentry

1. Marshal Kane stated in his 13 May report to the Police Commissioners, "I heard nothing more of these troops until twenty minutes past eight o'clock on the next Friday morning, April 19th," so the timing of Mayor Brown's excuse that they didn't know until later when & where the troops would come in, seems questionable. And since they knew they'd be coming into the President St Station, waiting at the Camden St Station with their police protection was at best a very poor plan.

2. The evening of the "riots" the marshal telegraphed his Rebels friends, according to court documents gathered in Volume 25 of Maryland Reports: Containing Cases Adjudged: "Thank you for your offer, bring your men in by the first train, and we will arrange with the railroad afterwards, send expresses over the mountains and valleys of Maryland and Virginia, for the Riflemen to come down without delay. Fresh hordes will be down on us to-morrow, the 20th; we will fight them or die. Geo. P. Kane," which suggests there was premeditation to the plan to drag Maryland kicking and screaming into the Confederacy.

3. When Mayor Brown ordered the telegraph lines and bridges burned around Baltimore that evening (something outside his jurisdiction and without the Governor's approval, although he tried to pin it on the governor) he showed his true colors.

4. And finally, the day after the "Pratt St. Riots" as the mayor made sure they were tagged for posterity, Governor Hicks sends a message that the Rebel militia had taken over Baltimore with the Baltimore politicos leading the way, per this telegram to the Secretary of War dated April 20th, 1861: “What they had endeavored to conceal but what was no longer concealed but made manifest, the rebellious element had the control of things.”

5. So even though the Rebels, suggested Old Abe violated their civil liberties (some even trying to sue the Federal Government for this dastardly deed), when he gathered them up and threw them in the Fort McHenry dungeons, I think the President showed great wisdom in letting them know he understood what they did without hanging them for their treason.

6. When the war was over, the history of the first battle of the Civil War was rewritten to suggest it was but a spontaneous riot of outraged citizens with our politicians as the heroes, instead of the true heroes who were the men of the Fighting 6th Massachusetts Volunteers, who fought their way across Baltimore with their flag still flying, two hundred and twenty-eight brave men against a mob of ten thousand.

Plug Uglies

On October 8, 1856, rioting overtook the city as the municipal elections were held. Two former railroad presidents, the American Thomas Swann of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and the Democrat Robert Clinton Wright of the Baltimore & Susquehanna Railroad, vied for the position of mayor. Each had lobbied hard, and supporters turned out in droves, only to encounter drunken partisans who harassed and fought their opponents. Tensions mounted as the day continued. In the early afternoon, a group of Plug Uglies and their Rip Rap friends encountered a group of New Market firemen near Lexington Market. Fighting broke out between the respective American and Democrat groups. Instead of using bricks and picks, this time the gangs came armed with muskets, shotguns, and blunderbusses. They even rolled in a cannon. Like an old movie western showdown, people fled the area as neighborhood residents locked up their homes and businesses. The Sun reported that the encounter went “unchecked and unheeded, apparently, by any show of police force.” The battle raged in “guerrilla fashion” for over three hours, killing Charles Brown and James Rodgers. Brown took a shot to the chest, while another shot sliced open Rodgers’ neck artery. Others were seriously wounded, including the Democrat Henry Konig, who caught a ball in his thigh, while another passed through American Boney Lee’s side and back. American Guy Silwright took three shots. Somehow, all three men managed to survive. One man named Feaster had a ball extracted from his leg at a local doctor’s office. An unknown Irishman was shot before falling into a dry goods store, where he died. Another man received a shot through his head, passing through his upper jawbone. Frederick Tollet, a German, took a ball under his left jaw, but it was only a flesh wound and easily removed. Thomas Morrison was shot in the leg. Martin Wooden was shot in the groin. The Sun remarked that the wound was “painful but not dangerous.” By early evening, the Americans had won the battle, which culminated in the group breaking off the doors of the New Market engine house. The Sun estimated that there were “perhaps some two hundred shots fired during this protracted warfare.” The rioting continued elsewhere—with different results. In the Eighth Ward, another group of Plug Uglies fought with a gang of Democrats. During the confrontation, several people were killed. A teenager from D.C. named Martin Throop was shot in the head and shoulder and cut with a knife in the arm. Although his brain protruded from the wound, he managed to survive for five days before dying. Daniel Broderick was shot and lingered for almost a month before finally dying. A Plug Ugly named Carter and Democrat Patrick Dunleavy were both killed. Unlike at the New Market engine house, the Democrats were the larger force here, sending the Plug Uglies into retreat. In other words, serious incidents occurred—and the fighting continued for days—but no other full-scale riots happened. In the end, American Thomas Swann carried the election, beating the Democrat Wright by 1,551 votes. Interestingly, for all his violent connections, Swann went on to become a largely progressive mayor, establishing the first streetcars and developing several city parks, including Druid Hill Park. He was reelected in 1858 after the newly developed City Reform Association’s candidate, Colonel A.P. Shutt, bowed out in the middle of election day itself. All of the violence meted out thus far was simply a prelude of what was to come. During the November presidential elections, former president Millard Fillmore, running as the American Party candidate, went up against Democrat James Buchanan. The current mayor, Samuel Hinks, wavered on whether to bring in military force to police the election. Governor T. Watkins Ligon, a Democrat, argued in favor of the plan, but Hinks ultimately decided against it, determining that the municipal police would be enough. Election day began much like the previous one had with small fights, growing anger and lots of drinking. By mid-afternoon, the fighting grew larger and more organized as Americans and Democrats again turned the city into their personal battlefield. Over a dozen people were killed, while more than 100 (some estimate 250) were wounded, including women and children. Mayor Hinks had been horribly mistaken. The police force was overwhelmed by the violence, with several members actively engaged in instigating it. In stark contrast to Baltimore’s fatalities, the Sun reported that in New York, there was some “fighting in the course of the forenoon in the course of which pistols and firearms were freely used, resulting in a plentiful crop of black eyes and bloody noses, but nothing more serious.” Fillmore won the state by more than seven thousand votes but fell short throughout the rest of the country. The American party was pro-Union, unlike the Democrats, who favored states’ rights. Meanwhile, in the more northern states, the Republican Party was growing at a feverish pace, replacing many American loyalties. While the American Party was being quickly dismantled on the national scale, it managed to retain its hold in Baltimore for several years, where the city’s long history of patriotism at all costs helped secure American sympathies. Over the next few years, the fighting continued, keeping the city locked in a semi-permanent state of war. Everything came to a head in the 1859 elections. Sick of the endless, constantly escalating violence, the city’s public began fighting back. On September 8, a large group of Baltimoreans gathered in Monument Square to “devise some means of rescuing our city from its present deplorable condition.” They drafted a number of “reform bills,” such as taking control of the police away from municipal government. A committee was organized with the valiant attempt to secure nominations of honorable selected from the best, most reliable, and most competent men in this community.” Meanwhile, the Know-Nothings held a counter-demonstration. They held up placards with a picture of a shoemaker’s awl and a caption reading, “With this we will do our work.” They even brought a blacksmith who forged awls on-site for participants. Mayor Swann refused to work with the reform association. He stood behind his administration and claimed: I do not hesitate to say that the press has done more injury to this city than ten times the catalog of rowdyism which it has professed to detail. It has excited your people to riot and bloodshed at home, and has brought discredit upon your good name abroad… If you go to other communities similarly situated as our own—with the same mixed population—you will find that rowdyism is not more remarkable in this city than in some of these. While the association failed to achieve all its objectives during the October election, it managed to accomplish more than any other previous attempt, including acquiring seven seats in the new First Branch of the city council. Unsurprisingly, election day was not without incident. Reform challengers and Know-Nothings knocked at one another all day. In the Twentieth Ward, men broke into the ward house and destroyed the ballots. However, their candidate, Henry Placide, disapproved of their actions and conceded. At the November election, violence again continued to reign supreme. George H. Kyle was one of many who submitted testimony to the Maryland House of Delegates about his experiences that day: I went to the polls about half-past 8 A.M. and was within two feet of the window; remained there about five minutes with my brother [Adam B. Kyle]. I had a bundle of tickets under my arm, and one of the men walked up to me and asked me what it was that I had. I told him tickets; he made a snatch at them, and I avoided him and turned around. As I turned I heard my brother say: “I am struck, George!” At that moment, I was struck from behind a severe blow on the back of my head, which would have knocked me down, but the crowd which had gathered around us was so dense that I was, as it were, kept up. After I received this blow I drew a dirk knife which I had in my pocket, with which I endeavored to strike the man, who, as I supposed, had struck me. I then felt a pistol placed right close to my head so that I felt the cold steel upon my forehead. At that moment I made a little motion to turn my head, which caused the shot of the pistol to glance from my head; my hat showed afterward the mark of a bullet which I supposed to have been from that shot. The discharge of the pistol, which blew off a large piece of skin of my forehead and covered my face with blood, caused me to fall. When I arose I saw my brother in the middle of the street, about ten feet from me, surrounded by a crowd who were striking at him and firing pistols all around him. He was knocked down twice, and at one time while he was down, I saw two men jump on his body and kick him… In the meantime I drew my pistol and fired into the crowd, which was immediately in front of me, every man of whom seemed to have a pistol in his hand and was firing as rapidly as he could; in this crowd, there were fully from forty to fifty persons. I saw at the second story windows of the Watchman engine-house building, in which the polls were held, cut-off muskets or large pistols protruding, and observed smoke issuing from the muzzles, as though they were being fired at me; then I turned toward my brother and endeavored to get to him. When within a few feet of him, I saw him fall…At the same moment a shot struck me in the shoulder, which went through my arm and penetrated my breast; from the direction the ball took, I am satisfied that shot was fired from the second story of the engine house… As I continued to back off a brick struck me in the breast and I fell… The crowd was firing at me constantly. When I arose…there were seven bullet holes in my coat and my coat was cut as if by knives in various places; the pantaloons also had the appearance of having been cut by bullets. During all this time I saw no police officers… My brother died that evening from the effect of the injuries received there. Between the violence and accusations of voting fraud, the Maryland state legislature decided that the election was illegitimate. It disbanded the old police force and developed a new one under state control. The reforms continued on the municipal level as well. The volunteer fire companies had already been dismantled and replaced with a new paid system “under the direct management and control of the municipal authorities”—an ordinance that Swann supported. In February 1859, the Baltimore City Fire Department had begun operation, immediately ending the rival company clashes and reducing the number of fires started on purpose by those companies. As a result of the changes, a Reform mayor and city council were elected on a remarkably peaceful day in 1860. The age of the Know-Nothing Party had ended the campaign in 1868, Republican candidates Ulysses S. Grant and Schuyler Colfax were matched against Democrats Horatio Seymour and Francis Blair. In an article for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, a Washington Evening Star reporter recounted his experience coming through Baltimore on board a train bound for Philadelphia, where he encountered “one of the most villainous and cut-throat looking mobs that ever disgraced even Baltimore.” The train first stopped briefly at Annapolis Junction, where a young man came on board and took a poll of who the men planned to support in the election. The reporter said that the boy “reported fifty votes for Seymour and Blair, forty-two for Grant and Colfax, and seven neutral or who declined.” Unbeknownst to the passengers, the information was transmitted ahead of the train to Baltimore in an attempt to “spot the Republicans.” Since many of those voting for Seymour and Blair were Baltimoreans, they got off the train when it stopped at Camden Station (today Camden Yards). The remaining passengers were primarily Republicans en route to Philadelphia. After the train’s three cars were decoupled, they were attached to horses to be taken across Pratt Street to President Street Station. The reporter described the terrifying incident that happened next: [The first car was] halted on the east side of President Street depot, [where] it was almost instantly taken possession of by a mob of roughs, upward of a hundred in number, who leaped upon the front and rear platforms, and occupied both doors of exit, so as to make sure of the passengers inside. The mob crowded against the windows, shouting for Seymour and Blair, which was their rallying cry. Then they flocked into the car and filled the passageway between the seats till it was impossible for the passengers to escape. The ruffians inside commenced an examination of each passenger. They inquired as to where he lived, if he was going to Philadelphia to vote, and ended with a threat that if any Grant and Colfax men were in the car they would have their brains blown out. A party of three or four accosted William Thorton, a Philadelphian, and assistant surveyor at the Metropolitan Hotel, Washington, who was sitting quietly in his seat, in this wise: The leader presented a cocked revolver, which he held directly against Thornton’s mouth, saying, “Where do you live? Are you going to Philadelphia to vote? Tell me quick, or I’ll blow your brains out!” adding a horrible oath. Thornton begged them to spare his life, and to mollify them, told them that he was one of Billy McMullen’s crowd in Philadelphia. The man with the pistol said, “You lie. I believe you are one of the Radicals going to Philadelphia to vote; and if I thought you were, I would kill you right here.” He added, in a threatening manner, “Who do you know in Philadelphia that can vouch for you? Tell me somebody I know in Philadelphia, or I will kill you,” still holding the pistol to his face. Thornton held up his hands and swore that he was telling the truth, when the ruffian left him, begging him to excuse them for having treated one of McMullen’s crowd so roughly, the ruffians for daring to look at them. He gave no provocation whatever. While this was going on inside, the crowd outside was incessantly yelling, “Bring them out. Kill every one of them! Don’t let one of them go on the train! Throw them under the cars!” The other passengers expected every moment to have their turn of cross-examination in the same style as that administered to Mr. Thornton, but before the examiners had time to go through the entire car in this way, the next one arrived, when the mob ran down toward it and beat several of the passengers in the most brutal manner. One passenger was pulled bodily out of the side window and kicked and beaten by the mob till they could pummel him no more. The third car arrived, and its occupants were treated in the same way; and after this, the ruffians staggered through the cars, shouting for Seymour and Blair, with imprecations that if any Grant and Colfax man dared to say he was for either of them, they would kill him on the spot. None of the passengers were armed, at least no weapons were displayed by them. The reporter then went on to describe an oddly comical incident. One of the assailants accused the passengers of cutting his head, and he threatened to shoot whoever had done it. Someone responded that it was a man in a light coat. The assailant grabbed a man matching the description. Before he could shoot him, someone else cried out, “That’s not the man; he’s in the last car.” The ruffian and his entourage rushed down to the rear car, but by this time, the train had started backing up. As the train continued down Canton Avenue, the mob followed it, but the violence had ended. The reporter noted that during the entire incident, he noticed that “there were three or four uniformed policemen present, who appeared either to fraternize with the rioters or to be afraid of them, for no arrests were made, as could be seen from the cars.”109 Not surprisingly, Seymour and Blair won Maryland, along with seven additional states. However, they were no match for Grant and Colfax, who carried twenty-six states and won the election.

The Plug Uglies II

The Plug Uglies were a street gang (though most often referred to as a political club) that operated in the west side of Baltimore, Maryland from 1854 to 1860. The Plug Uglies coalesced shortly after the creation of the Mount Vernon Hook-and-Ladder Company, a volunteer fire company whose truck house was on Biddle Street, between Pennsylvania Avenue and Ross Street (later Druid Hill). They were originally runners and rowdies affiliated with the Mount Vernon. Plug Ugly captains included John English and James Morgan. Other prominent members were Louis A. Carl, George Coulson, George "Howard" Davis, Henry Clay Gambrill, Alexander Levy, Erasmus "Ras" Levy, James Wardell, and Wesley Woodward. The gang associated with the emerging American Party (the Know Nothings) in Baltimore.

Like similar associations in Baltimore and other United States cities during this period, the Plug Uglies' street influence made them useful to party politicians anxious to control the polls on Election Days. The Plug Uglies were the central figures in the first election riot in Baltimore in October 1855. Together with the Rip Raps, they were also actively involved in deadly rioting at the October 1856 municipal election in Baltimore and in similar violence at the Know-Nothing Riot in Washington in June 1857. At the Washington riot, the National Guard called out to quell the fighting, shot and killed ten citizens. Accounts of the Washington riot appeared in newspapers nationally and gained widespread notoriety for the Plug Uglies.

Besides election-day fighting, the gang was involved in several assassinations and shootings in Baltimore. Most notably, Plug Ugly Henry Gambrill was implicated in the murder of a Baltimore police officer in September 1858. Gambrill's trial (presided over by Judge Henry Stump) and the subsequent deadly violence relating to it, made the crime one of the most sensational of the era.

The violence of the Plug Uglies and other political clubs had an important impact on Baltimore. It was largely responsible for the creation of modern policing and a paid, professional fire department, as well as court and electoral reforms. These reforms, together with the election of a Reform municipal administration in October 1860 and then the Civil War, led to the breaking up of the Plug Uglies.

Know-Nothings