1800 - 1900

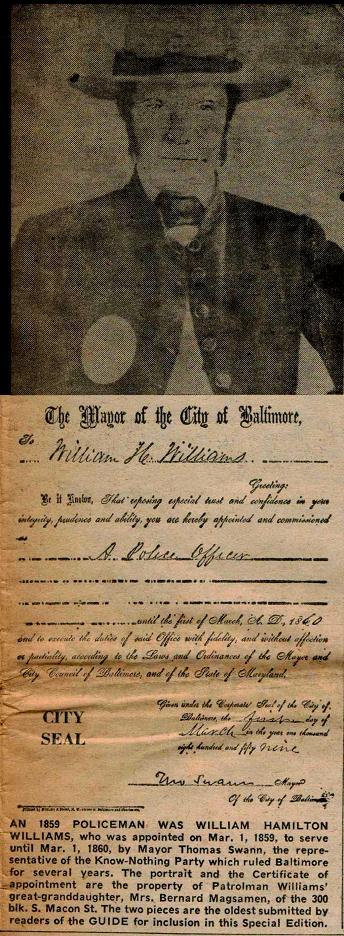

BALTIMORE CITY POLICE OFFICERS

We can’t all be heroes; Somebody has to sit on the curb and clap while they go by!

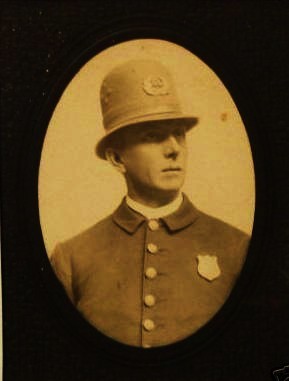

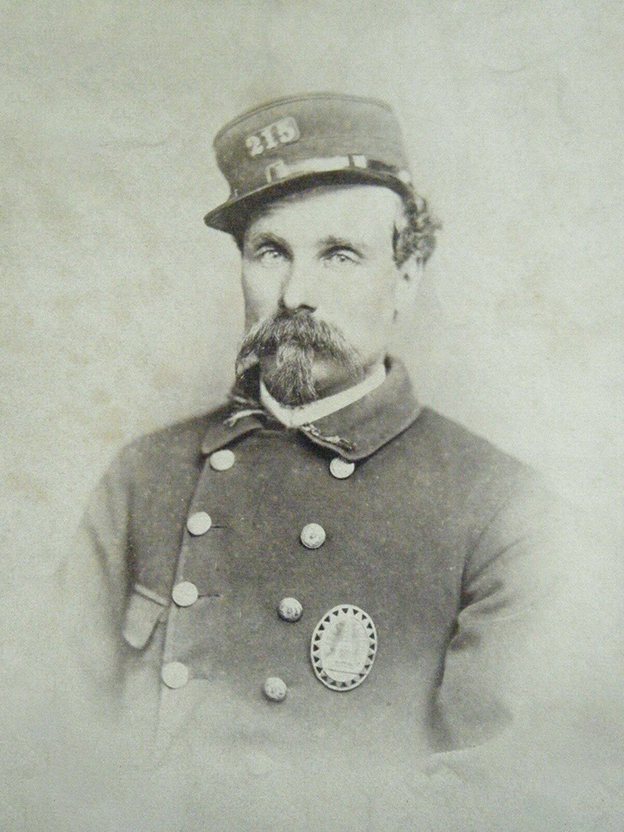

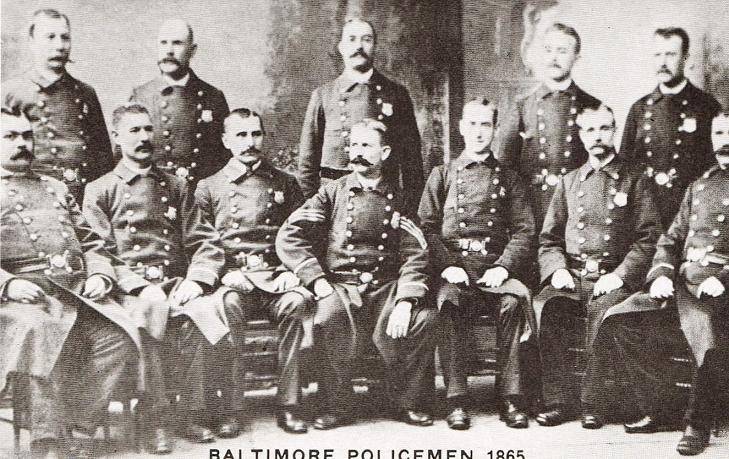

1866

1866

Issac, brother-in-Law of Augustus and Joseph.(below)

Information provided by Richard Johnson a family member presently living in Glen Burnie, Maryland.

Apr 25, 1937

Baltimore's Police Department--A Checkered Career

LEON JACOBSON The Sun (1837-1987);pg. 60

Baltimore’s Police Department – A Checkered Career

Corruption of Force in the Know-Nothing. Led to Abuse, and State Intervention

Free Elections Assured After Writing and Intimidation of Voters of Earlier Day

By Leon Jacobson

The anomaly of a local police force, maintained by municipal bonds, began under the control of a state agency obtains in only three of the 10 largest cities in the country – Boston, St. Louis and Baltimore. This gives rise to an especially particular situation here, with General Charles D Gaither’s third term as police Commissioner coming to an end in May. His successor will be appointed by Gov. nice, who was rejected at the polls by the city in 1934 and who was carried into office only on the both of Baltimore County. The beginning of state authority over the city police dates back to the most disgraceful era in local history. From its origin in 1784 to 1860 – the police force had been under control of local officials. By that time, however three or four decades of ebullient politics and contaminated it and that body had become so corrupt and ineffective that the state was compelled to assume authority over it. In 1863, the legislature enacted a law created a board of four police commissioners, but subsequent legislation made the commissioners appointed of by the governor and, later, establish a single Commissioner in place of the board. Gen. Gaither, appointed by the late Gov. Ritchie in 1920, was the first single head.

MOBTOWN RIDING

Sporadic writing and mild violence especially around election time had by 1825 already one for the city the soubriquet Mobtown. But the Mobtown epoch in local history is generally considered to have lived and died contemporaneously with the know nothing party, because it was not until the introduction of this party locally that politics found the lowest depths of depravity, and democracy, here at least met its greatest challenge.

Preaching and anti-alien, at the Catholic doctrine, the know nothings known also as the American party first appeared here as a secret order in 1852, probably in the month of October. The time, however, was not yet ripe for such a movement to make an impression, the old parties being too entrenched for this newcomer to edge into the field. But the temper of Pre-Civil War politics was rapidly melting the national solidarity of the old parties and as the weekend nationally, so they did it locally. The know nothings, appealing to the considerable anti-alien sentiment latent in the city and counties, made the most of the situation.

VICTORIES IN 1854

In 1854 – their mayoralty candidates one in Cumberland and Hagerstown; in 1855 – they added Annapolis and Williamsport. In 1856, they completed their meteoric rise. The city and 13 hour of 21 counties were now arranged in their column. With his first taste of success – the party had discarded its secrecy and division into covert councils and had reorganize itself in the clubs bearing such candidly prophetic names as the plug uglies, tires, rough skins, bloody tubs and black snakes. In educating the public, these clubs recognized no law. It became their duty to stuff the ballot boxes and terrify the opposition. Their methods – or rather there implements – of persuasion – were shoemakers awls – slingshots – truncheons – mortar lives – pistols and muskets. Scores of dissidents were hustled into damp sellers until the balloting was over. They were beaten and robbed in the process. Others were forcibly intoxicated and was to the polls to vote the right way. (Note there is a rumor that Edgar Allan Poe was one of those forced to intoxication and made the boat at several voting boxes is said this is what led to his death)

Incendiarism was not infrequently practiced. The opposition’s pre-election meetings were with sleep broken up. After one election – eight were reported killed, 150 injured. Not only men but little boys were said to have gone around armed with guns during periods of political excitement. In one instance, a small cannon was brought into play. In this manner, half of the electorate was deprived of its right to vote.

WHAT WERE THE POLICE DOING ALL THIS WHILE?

Prior to 1856 – they had put forth some effort to quell disturbances and preserve order. But they had been unable to cope with the situation for two reasons. First, the other parties had been employing an election tech make just as diabolical as the know nothings, albeit with somewhat more discretion and conscience: and second – they had not been properly upheld by the magistrates in the discharge of their duty.

FREQUENT ARRESTS

In one year – the police commanded by one Capt. Brown of the Western district – arrested one man more than 100 times – only to have him released in each instant by the magistrate. Police officers at the time claimed that they would arrest from 25 to 50 miscreants in one night – but their prosecution would go to naught and their prisoners of their homes. Perhaps no single event or person was more characteristic of the debasement of the day than one judge stump of the criminal court. He was notorious for his loose habits and disregard of the conventions of civilized society and the dignity of a court. He was frequently picked up by the Nightwatch for his convivial habits. His judicial career and it ultimately with impeachment.

END OF POLICE

After 1856 police intervention became an impossibility and order of far-off abstraction. In that year a know nothing mayor was elected and the force soon became permeated with partisan politics. The police, who previously had been making an attempt, how-ever futile, to enforce the law, now became tools in subverting it. The first hint of form occurred just before the state elections in 1857. The near – anarchy attempted every election had been adversely affecting local business. The riding and disorder had secured hundreds of County merchants away from the city and the local tradesmen were determined not to lose out again. Consequently, they combined with those of the electorate who did not participate in party politics and presented being deprived of their vote and argued Governor Ligon, a Democrat, to take measures toward ensuring a peaceful election.

MAYOR REFUSES

Moved by his sense of duty and, undoubtedly, also by his animosity toward know nothing mayor salon – the governor acquiesced. He came to Baltimore and, by letter, invited the Mayor to cooperate with him in the enforcement of all during the approach and election period. The mayor refused blatantly, informing the governor that local law enforcement was his business and not the concerns of the state. The governor, disregarding the mayor’s reply, proceeded at once to make military arrangements for the maintenance of peace. He ordered Maj. Gen. John H. Stuart, of the first light division, to hold his command ready for service: Maj. Gen. John Spears Smith was ordered to enroll six regimens of not less than 600 men each. To arm the equipment this forest – 2000 muskets were barred from the governor of Virginia. At the same time governor Ligon issued the following proclamation; “Having been credibly informed by a large and respectable number of citizens of Baltimore that serious apprehensions are and entertained that the approaching general election is threatened with extreme violence and disorder in this city, sufficient to terrify and keep away from the polls many peaceable voters, unless the civil arm is vigorously interposed for their protection… And having solicited his (Mayor’s) cooperation… And having received from him no favorable response… I hereby proclaim that I have directed the proper military officers to enroll and hold and readiness their respective corpse for active service at once, and especially on the approaching day of election…”

SPECIAL POLICE

But the military range the governor did not prosper, for in his own words, “that class of citizens who military service is mainly to be expected exhibited first, indecision, and, at last, unwillingness to respond to the call which had been made upon the community.” As a result, the mayor agreed to appoint 800 special policeman among the members of the two major parties (he refused, nevertheless, to choose half the number from the ranks of the Democrats). But nothing came of it. The special police were powerless without the support of the regular force. Those who were to conscientious were told to leave the polls – as they had no business there. Many of them tendered their resignations to the mayor before the day was over.

ROUGHING VOTERS

What is the election was with neither riot nor bloodshed, but fraud and intimidation rendered it anything but democratic. The roughs at the polls employed a regular system of signals to indicate the reception to be accorded the voter. For example, as the gator approach, he was solicited by a party heeler and, if he were voting the Know Nothing ticket, the healer would try out: “clear the way: let the voters come up.” But, if he were to decline the Know Nothing ticket, the healer would shout: “meet him on the ice” and the voter would some really be pushed away from the window and into the street. When men were assaulted, the police either arrested them or tried to persuade them to leave the polls. The assailants met with almost no opposition. But deliverance from these chicaneries was not far off. The state election of 1859 signal the decay of the know nothing party. The know nothings carried the city by large majority. But the counties discussed it with the state of affairs in the city, revolted and went into the Democratic column, the result being the legislator for the first time in several years was decisively not Know-Nothing.

BALTIMORE POLICE

One of the first matters to engage in the legislation attention was the question of a proper police force for Baltimore: in one of the first acts passed was one taking control of the police away from the mayor and placing it in the hands of the board of four commissioners elected by the legislature. By 1860, the know nothings had outlived any definite principles accept an attempt to obtain public office. In the local election of that year, they made their last stand. But, we can by internal wrangling’s and missing the aid and comfort of a friendly police force, they were forced to retreat never to reappear on the local political front. The Civil War came the following year and claimed the energy of those turbulent spirits who had been keeping the city continually in a state of warfare.

NOT ALONE

Baltimore was not alone in surrendering control of its police to a state agency. Many another city was also afflicted by the seething politics of the middle decades of the 19th century: and many another police force was given to corruption. As a consequence, it became the fashion of the day to relinquish authority in favor of the state.

State control had been justified mainly on the grounds of police were primarily occupied with the enforcement of laws passed by the legislator and intended to operate uniformly throughout the state. Therefore, it has been argued, they are not agents of the municipality, but rather of the state whose laws they are under oath to execute.

On the other hand, the argument is advanced that since the municipality pays for the maintenance of the police force, it should retain supervisory power over it. In most instances, nevertheless, with the restoration of water, authority has been returned to local hands. But not so here. Probably, because the behavior of our police during the last 77 years has not been so bad as to warrant a change, and probably also because a change is not in itself a guarantee of improvement.

Baltimore Flood

1868 - Friday, July 24, 1868 - The Baltimore Flood overtook the city. In a crisis the bravery of Commissioner Carr in rescuing the victims of the catastrophe, became a matter of national fame. Harper's Weekly, at the time, in a long article on the floods, quoted the following editorial notice from the Baltimore Sunday Telegram, of July 26, 1868: "It is a true saying, that in times of great public calamities, some men rise to the position of a greatness, and such was the case with Police Commissioner James E. Carr. He at first sight apprehended the character of the calamity, and he immediately sent for boats and organized a sufficient force of policemen to manage them. He soon had work enough to do. He led the van in his boat in places of great peril, and rescued women and children preventing them from drowning in a flood the likes of which Baltimore has never seen. The part most difficult to explain, is the rapidity with which the streams rose. The Patapsco River at Ellicott City and Jones Falls, rose at the rate of five feet in ten minutes; the water came down those streams like a great wave on the sea-short. The river at Ellicott City rose ten feet before a drop of rain had fallen there, and was at one time forty feet high. In this city the rise was so rapid that a gentleman entering a cigar store from a dry street returned with a lighted cigar to find himself knee deep in a rapidly rushing stream. A passenger car, while crossing a street, was caught by the flood, and with its passengers was swept several blocks toward the river. The market men were caught at ' their work, and only had time to get on their benches and stalls for safety, and these were washed away with their occupants. Terrible as was the catastrophe in Baltimore, it was much worse in Ellicott City. Had it occurred at night the loss of life that it must have caused is fearful to contemplate! It was about ten o'clock in the morning when the water first rose above the banks of Jones Falls, and began to flood the low streets of this city. Slowly, at their beginning, the floods covered Harrison street, but in a moment they rushed down Harrison street, increasing in volume at each minute, until the bed of the street was filled with a swollen and powerful stream, whirling on in its surface the shattered remains of ruined homesteads, wrecks of furniture, and, in fact, almost everything in ordinary and common use. When it reached Baltimore Street the stream divided into three currents. One rushed like a torrent to the right, the other to the left, and the third ran with more slowness down the center of the market. Above the roar of the vortex could be heard the shrieks of women and children, and the cries of men for help, as they were whirled along with the furious current. Even carriages, with their occupants, were caught up and carried along. For some hours after the awful scenes of destruction had begun in the center of the city, the greater part of the population of the upper portions, kept indoors by the pouring rain, had no idea of the dreadful occurrences below. An extra edition of the Evening Commercial, published at about two o'clock, gave them their first intimation of the disaster. When the flood first appeared on Harrison Street the police busied themselves aiding the residents of the street to carry their household goods to places of safety. In a few moments, however, they were obliged to turn their attention towards rescuing the people themselves. Alarms were rang, and men called in from all the stations, to the scene. Numerous boats were promptly ordered from the wharves by the Police Commissioners, and were hurried to the inundated district. They were manned by experienced boatmen and police men. Most of the boats were launched from the Holiday Street Theater, and were sent thence, under the direction of Commissioner James E. Carr, through Calvert, North Holiday, and other streets, for the purpose of removing families and furniture to places of safety!!!

Marshal Kane 1860

Apr 29, 1861

PROHIBITING THE DISPLAY OF FLAGS The Sun (1837-1989); pg. 2 Prohibiting the display of flags. At this very critical juncture of opinions on Bunting, the pulling down of an American flag by order of the board of police is an act which a little preserve ingenuity may distort into an atrocious, not to say flag-itious, offense. But the times require good men to be true and reasonable. We are very sorry to find some disposition prevalent to deal unjustly and mischievously with this matter. We can say, with the knowledge of the fact, that our excellent board of police have done several things which none could regret the obvious propriety of doing more than they. Yet in all they have done. Where is the man among us who will say he has suffered the privation of any civil right at their hands? Just think for a moment of the wonderful preservation of the general peace and order of the city seem to tearfully exciting times of the last few weeks. Think how the turbulent elements of the city have been subdued. Think how few Outrages have disturbed our sense of right and justice, when the inflamed populous were bent on securing arms by any means. Think of the mild but effective restraint exercise over the whole community one passion and resentment stirred the whole city to go forth and make war upon the Pennsylvania volunteers at Cockeysville, and happy termination of that affair and sending out to them an abundance of food to relieve their family shooting condition. And think about this is the worst that can be said of that good old Baltimore, which they so lustily abuse in the North, which, as it comes to its senses, will be induced to do us justice, while the South can really have no good cause of complaint against us.But to the flag affair. Our citizens know very well that those whose taste for the display of flags is so exceedingly susceptible. Enjoyed the opportunity of giving the nation Bunting to the breeze on the fall of Sumpter. For several days sympathy with the administration and hostility to the south was expressive in this way at several places in the city and did some newspaper offices. Then came the sad affair of Friday, the 19th, after which, and suddenly, the Confederate flag was in the ascendant, and the emblem of the Southern Confederacy was everywhere, while the national flag was voluntarily retired. But our readers are not all where that one a rush was made upon the corners of the Minutemen to pull down the American flag, the first man who appeared to stop the lawless movement was Mr. Davis, one of the board of police, and to at once resisted their purpose. The flag remained, and was removed voluntarily and that leisure by the Minutemen themselves, under the unpleasant feeling that seemed to associate their sympathies with those who had shed the blood of our own citizens.And a word here upon the Confederate flag demonstration. That was by no means what it has been supposed to be – a secession demonstration. It was an exhibition of that feeling which still pervades pretty nearly this whole community – an unwavering devotion to southern rights. And the mistake still prevails the north that the union men of Baltimore are in different to southern rights: if this is not an egregious mistake, we have misunderstood at her own citizens.The southern rights demonstration, through the exhibition of respect for the southern flag, was apparently all but universal until a few days ago when it was ascertained that a union flag was to be hoisted at two or three places in the city. The fact was one to be seriously considered apart from any disposition to oppose the hoisting the United States flag. It was a question of the same importance, had it been a white sheet, with the same probable result the belief was consistently entertained by the commissioners of police that if they did not prevent the movement or take down the flag, a mob would have attempted it, a desperate riot would have ensued, and the peace of the city have been murderously and possibly overwhelmingly destroyed. Accordingly, true to their office, and the impartial execution of their duty, they issued an order that flags of every description should be withdrawn during the session of the legislature. When that order was issued, there were nothing to be seen but the Confederate flag and the arms of Maryland. Instantly all these flags were withdrawn: but the flag of the union was run up on Fells point and on federal Hill, and the collection of men had rallied to defend them and defy the police. Then it was that the police authorities insisted upon compliance with their orders. The union flags were taken down, and the peace maintained and that good peaceful citizen will not admit that it is far better for the display of flags should be temporarily suspended, rather than the piece of the city be so needlessly disturbed?Amputations against the police are easily made, and sensor is a flippant thing when reason is an abeyance. But peace and good order we enjoy is worth 10,000 times over the display of a flag. Men can cherish their peculiar views, and maintain their associations without Bunting, at least during a period of great domestic excitement.

Photo courtesy of Gualtiero Fabbri

A Colt 1849 Pocket Model

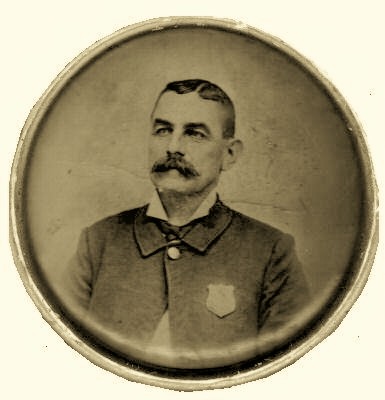

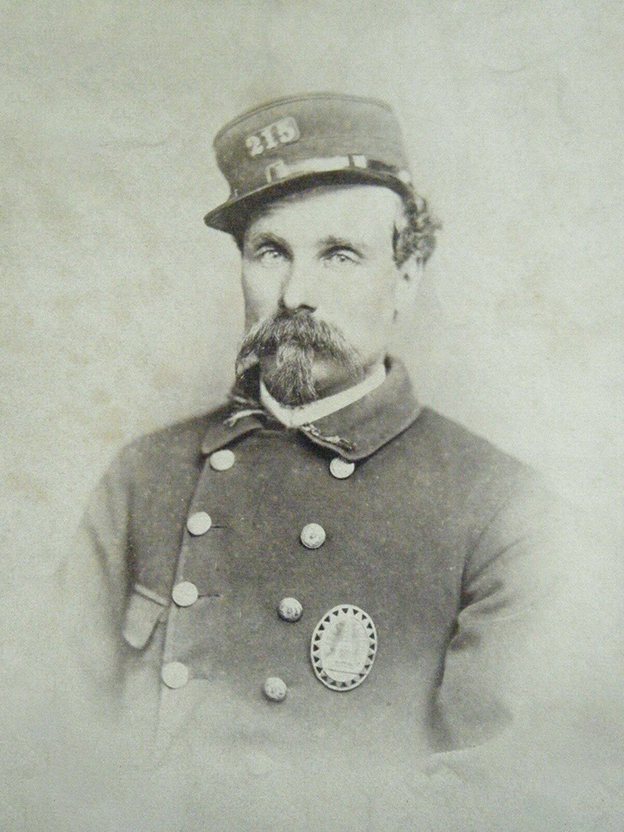

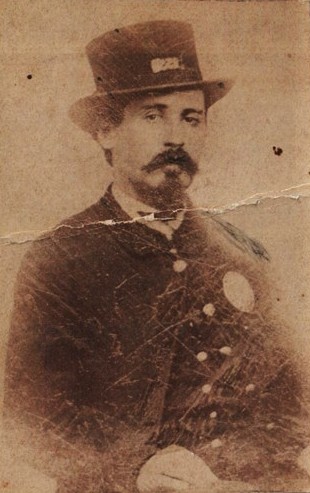

Issac Henry Jackson

Born: Dec.5, 1820

Died: Aug. 21, 1867

1855-1856: Baltimore (Watchman) Police

1857-1860: Baltimore Police Officer

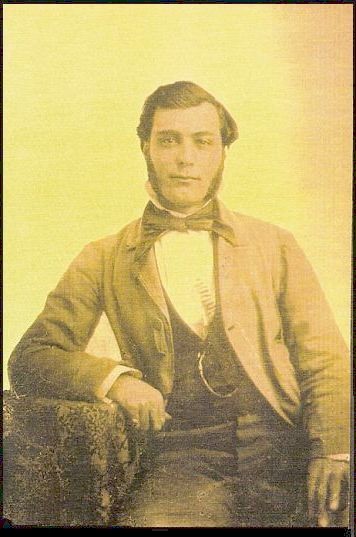

Samuel Johnson, (no photo available) father of Augustus, Joseph and Caroline Johnson (wife of Issac Henry Jackson )

Born: Feb.22, 1798

Died: Jan: 21, 1871

1855-1857- Baltimore Watchman (Police)

1858-1862- Turn-Key Southern District

1862-1868- Keeper of Battery Square (Riverside Park)

1869-1871- Watchman

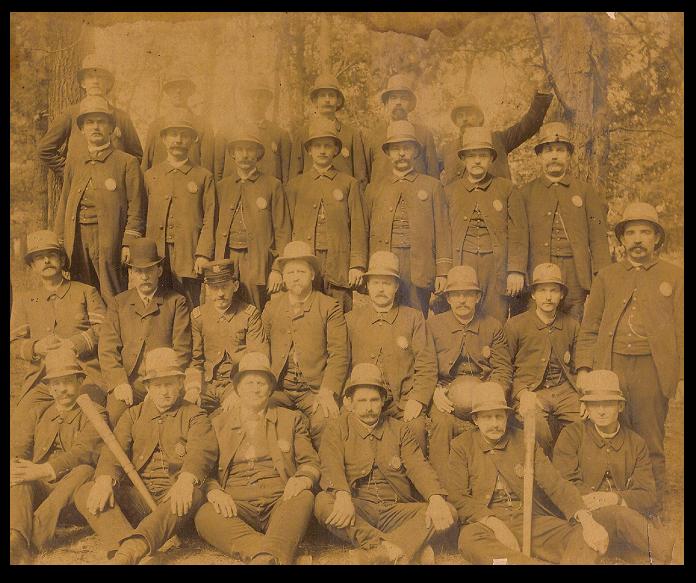

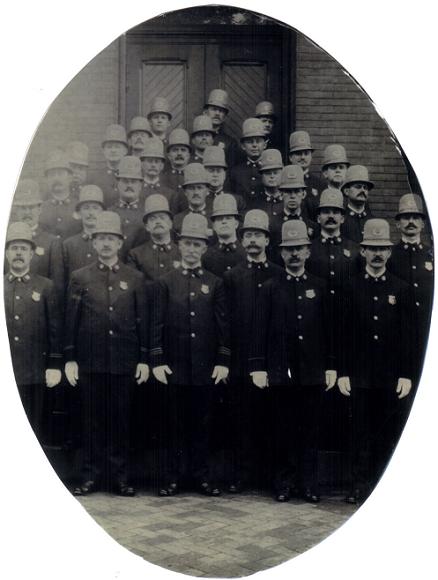

Voters and police assemble outside a barbershop turned polling place. Before the Civil War, election violence was so prevalent that wags often referred to Baltimore as "Mob Town." This early twentieth-century image suggests that elections still attracted a police presence.

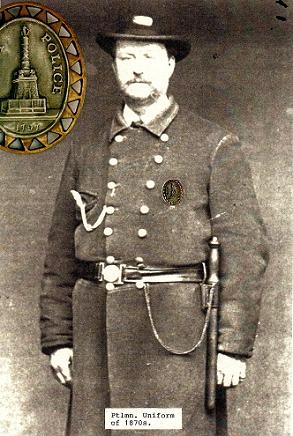

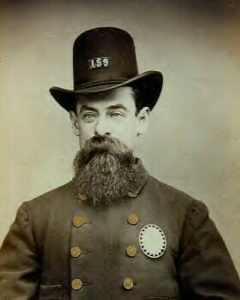

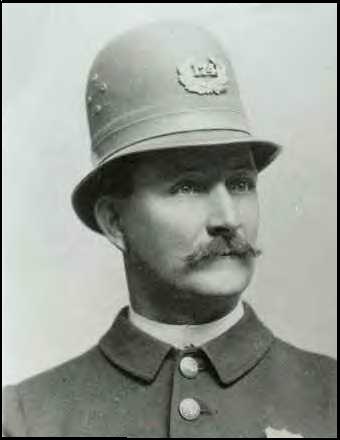

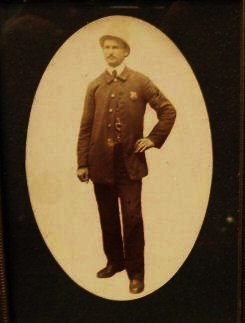

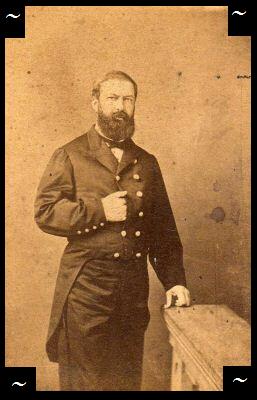

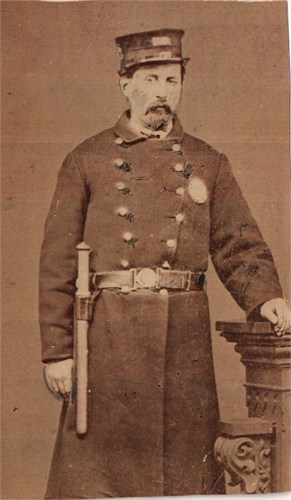

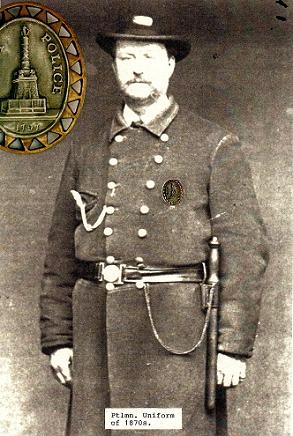

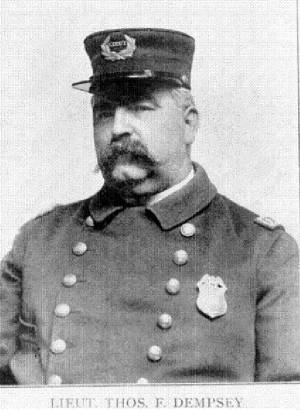

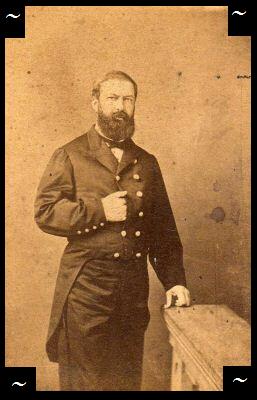

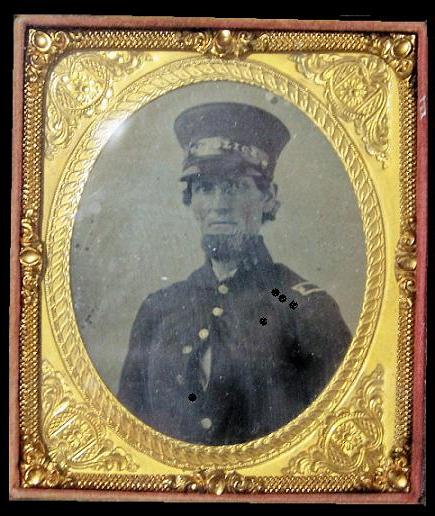

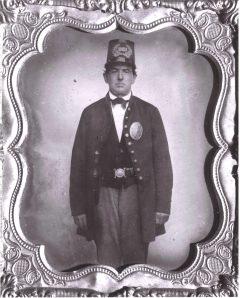

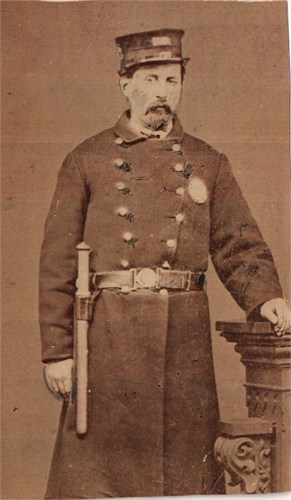

Baltimore Police Lieutenant circa 1860's

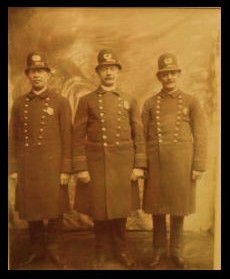

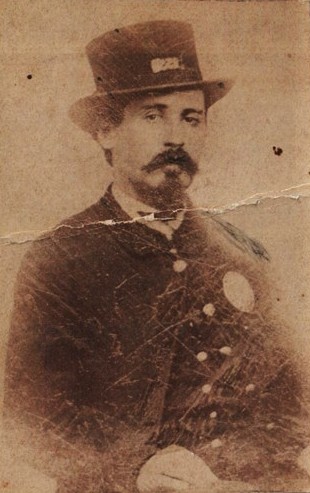

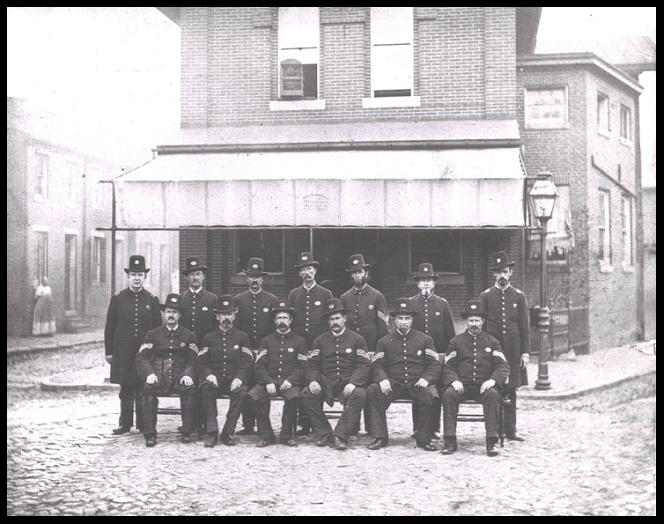

J. Thomas Arthur was born on 4 April 1840 in County Clare, Ireland. He was in Baltimore by 1864 (above)

Officer Arthur served in Baltimore City's Police Department at the Central Station.

In the photo, Officer Arthur is the older gent seated on the right side of the picture. (below)

The photo of the Central Police Department was taken about 1890. Notice the details, brass lamps and sconces, polished furniture with turned legs ... there's even a telephone on the desktop at the left.

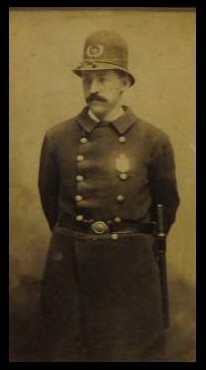

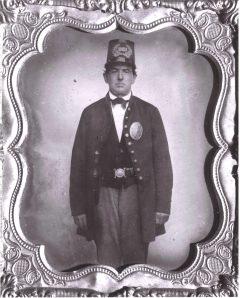

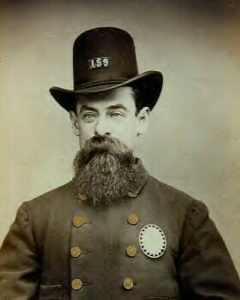

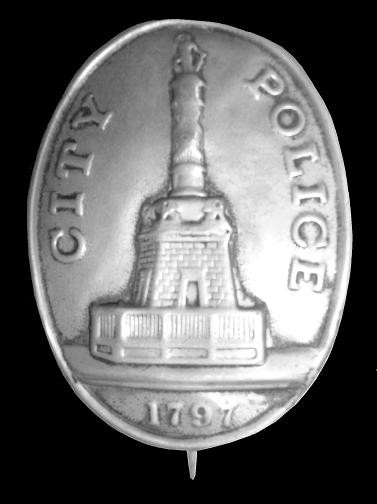

OFFICER JOHN WEITZEL DISPLAYING SECOND ISSUED BADGE 1860

17 September 1910

Why The Control Of The Police Board Was Given To The State

Inasmuch as there has recently been some talk of restoring the complete control of the Police Department of Baltimore back to the state. It might be an opportune time to recall the reason the appointment of police Commissioner was committed to the state the first time. In 1860 the police commissioners were appointed by the Mayor and City Council under a law authorizing them “To Establish Night Watch or Patrols and to erect Street Lamps.” Soon after the enactment of this old law the police force became a political machine in the hands of the Mayor. In the 1850s, when the “Know Nothings” were in control of the city and the various societies known as “Blood Tubs,” “Plug Uglies,” “Rednecks,” “Pioneers,” “Spartans,” “Regulators,” “Black Snakes,” “Tigers,” “Eubolts,” “Rip Raps,” “Ranters,” “Little Fellas,” etc., ran riots on election days, the police became an element of the mob. In 1837 a city reform association was organized and issued an address to the people, in which it was declared that there was no reasonable and sufficient security in Baltimore for persons, property or franchise.

The Central Reform Committee in 1859 declared that the police, with a very few honorable exceptions, openly sympathized with the rioters at the November election and in almost every case arrested those who were assaulted by ruffians. The Reform Convention of 1859 appointed a committee to draft loss to reform the city government. The committee was composed of William H. Norris, Philip Francis Thomas, I. Nevitt Steele,, S. Teakle Wallis, and Nielsen Poe. The election of 1860 was carried by violence, but the legislature unseated the whole city delegation, and, at the request of the city for the preservation of peace and good order, enacted the Jury Law and the Police Law – the latter drafted by Mr. S. Teakle Wallis. That law, passed at the urgent request of the city, took the appointment of Police Commissioner from the city and confided it to the state, where it remained until 1978.

The act of 1860, chapter 7 – which reorganized the police force, retained a singular provision, which it is believed was not in the original draft as written by Mr. Wallis. It is as follows: “provide, also, that no black Republicans or endorser or approver of the Helper Book shell be appointed to any office under said board.” This law created four Commissioners, to be elected by the Legislature, the first board being named in the bill – namely, Charles Howard, William H. Gatchell, Charles D. Hinks and John W. Davis. The board appointed Col. George P. Kane Marshall of the police

The Board of Commissioners continued with four members until 1874, when it was reduced to three. The board was Democratic until 1897. In 1896 the first Republican Legislature was elected, and two Republican Commissioners, Mr. Johnson and Mr. Heddinger, were appointed. From 1897 to 1900 the board was Republican. In 1900, at the request of the city, the appointment of the commissioners was committed to the Governor, where it would remain until 1978. The reason for the change was to put the responsibility for the character of the board upon the Governor. The responsibility of the Legislature was not personal and constituted no restraint. A strong effort had been made in the Republican Legislature of 1898 to give the appointing power to the Governor. A Republican caucus nominated Mr. Frank C. Wachter for Commissioner, but because of divisions in the party the election did not take place, and Mr. Schryver, the only Democrat on the board, held over.

At this session a number of different bills to give the appointing power to the Governor were introduced. Senator S. A. Williams, of Harford County, introduced one of them, and this, we believe, was supported by Senator Putzle, then representing one of the city districts. An amendment was offered by Senator Wescott, of Kent County, giving the appointment to the Mayor of Baltimore. This was rejected all three of the city senators – Putzle – Dobler and Strobridge – voting against it, although all were Republican, and there was at the time a Republican Mayor. Governor Crother, then Senator from Cecil County, introduced two bills for the appointment of the Commissioner by the Governor. One of them provided for a bi-partisan board, two Commissioners from each party. But all the bills failed.

The Reorganization bill of 1900, which was passed by the Legislature, was introduced by a city Senator and was voted for on its final passage by the two city Senators who were present – to wit, Senators Brian and Moses.

The record here presented is given to show that the appointment of Police Commissioners was first taken from the Mayor and City Council and put with the Legislature at the request of the city. It was then taken from the Legislature and given to the Governor upon the initiative of the city and by the action of the representatives of the city in that Legislature. There was never in this connection any assault by the counties upon the home rule of the city. As it is, while the appointing power is at Annapolis, the Police Commissioners must under the law be “three sober and discreet persons, who shall have been registered voters in the city of Baltimore for three consecutive years next preceding the day of their appointment.”

Photo courtesy Mrs. Karen Kidd

Detective Albert Gault

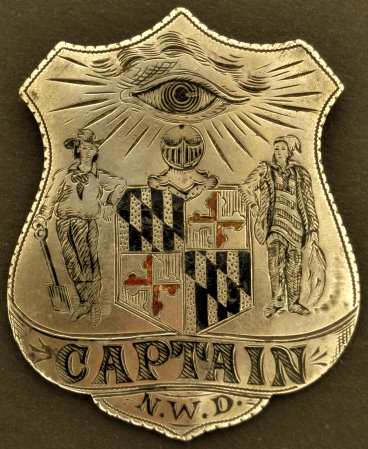

Actual Baltimore Police badge worn by Detective Albert Gault,, who was a Baltimore City Policeman and Detective from 1866, when he joined the force, until his death in 1900. Detective Gault was a celebrated Detective who was involved in numerous cases during his tenure. The book, entitled "Our police: a history of the Baltimore force from the first watchman to the latest appointee", by De Francias Folsom. Chapter X has about twenty pages detailing some of Detective Gault’s cases. (Note that this badge is the center piece of the first issued star badge in 1851. Only the center piece was worn by detectives to make easier to conceal on the detective's belt or inside his jacket) This badge was found by Detective Gault's relatives among his personal effects.

Obituary for Albert Gault,

Detective Baltimore City Police Department

Detective Gault is Dead

His skill and daring in the pursuit of criminals

July 27, 1900

Detective Albert Gault 63 years old, died at 10 minutes past 4 o'clock yesterday afternoon at his house at 1538 W. Lanvale Street where he had been suffering with stomach trouble for the past 6 months. He had been sinking but Wednesday evening there was a decided change for the worse. He had wasted away to a skeleton having taken no nourishment for weeks, but was conscience until the last. Mrs. Gault and all her children except one, Mr. James W. Gault were present. He arrived last night from Connecticut. The children present were Mr. Robert H. Gault, Miss Kate Gault and Mrs. Edwin Kapp. Mrs. Gault was Miss Sarah Ellen Harrison. She and Detective Gault were married in 1860. Detective Gault leaves one sister--Miss Sallie Gault and two brothers, Messrs. Richard and William Gault. The funeral will probably take place Sunday afternoon. Rev. J.P. Campbell, of the Faith Presbyterian Church, Middle Street and Broadway will conduct the services. The interment will be in Greenmount cemetery. The undertakers are Evans & Spence. Detective Gault was a native of Baltimore and a son of Mr. Robert Gault a well known typefounder. When 14 years old, after spending several in the public schools. Detective Gault served an apprenticeship with the gas-fitting firm of Blair & Co. He followed the trade for 13 years. In 1864 he was appointed on the police force and assigned to work in the Central District under Captain John Mitchell. Very soon afterwards attention was attracted to his "detective" qualities by his prompt discovery of over $7,000 worth of goods from Thompson's tailoring establishment on Fayette Street.

During the flood which occurred July 24, 1868 Patrolman Gault attracted attention by saving with great risk to himself two persons from drowning. He was an excellent swimmer. In 1873 while serving under Captain Lannan he was promoted to Sergeant and in the same year was assigned duty as a detective. Among the noted instances of his work as a Detective was the discovery and arrest of the negro, Harris, who was charged with having assaulted a young woman of Saulda, Va. The negro was tried and sentenced to death, but the sentence was commuted to 25 years imprisonment. Detective Gault made several daring arrest of fugitives from justice charged with assault but one of his best pieces of work was the arrest of Marshal Price of Caroline County who was charged with the murder on March 26, 1895 of Sallie E. Dean, a 14 year old girl. Price afterwards was lynched. Detective Gault was also largely instrumental in solving the mystery connected with the murders four years ago in Charles County of the wife and niece of Joseph Cocklag. An instance of his pluck and daring was the bringing to Baltimore from Detroit, Mich., in 1876 Joseph Lewordrell who had robbed Mrs. Lenka, a polish woman, living on Broadway near Thames Street of about $1,000. While the train was passing through the mountains of West Virginia the prisoner whose handcuffs had been removed for a moment, suddenly dashed out of the car door and jumped off the train which was running at full speed, the train was stopped and the detective, unarmed, pursed the fugitive 12 miles through the mountains, recaptured and tied him and flagged the first train. The conductor allowed the two men to get on, but concluded that they were tramps, was about to put them off when a passenger on the train recognized Detective Gault and he was allowed to continue with his prisoner to Baltimore. In September 1895 at Orlando, Fla., he arrested Robert Beason, alias Frank Smith, alias Frank Lefton, alias Clark who defrauded the commission firm Biedler and Jackson, 113 south Charles Street out of over $500. Beason had been a motorman, a check forger and fugitive from justice for many years. Detective Gault had traced him to Florida and returned with the prisoner to Baltimore, he learned on the train that friends of the prisoner had arranged to affect his release. Before arriving at the place where the rescue was to have been attempted Detective Gault got off the train and taking Beason into a swamp, hid there until the next day, when he continued his trip to Baltimore uninterrupted. In the Perot abduction case Detective Gault was commissioned a United States Marshal and sent to England with extradition papers to bring Mrs. Perot back to this country for trial. He was detained in London for over a month, while there a great reception was given him by the London Detective force of Scotland Yard. His death occurred on the anniversary of the day he sailed on the Majestic for London July 26, 1899. Information provided by Mrs. Karen Kidd, who provided a copy of the original newspaper article. (This site and family members are in search of a photo of Detective Albert Gault.)

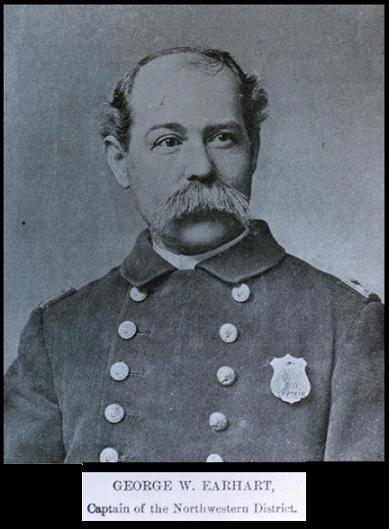

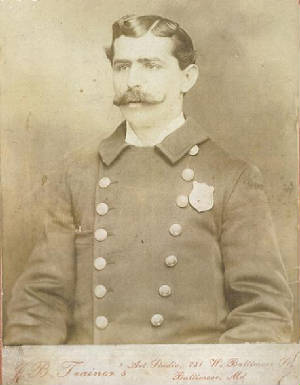

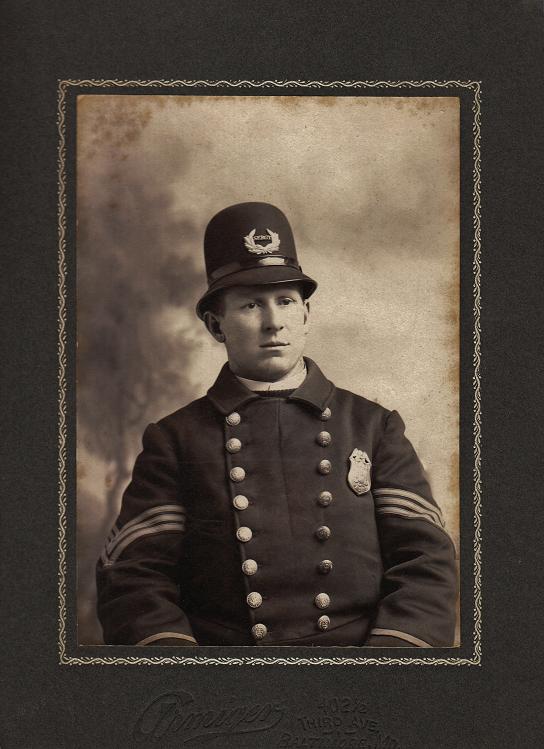

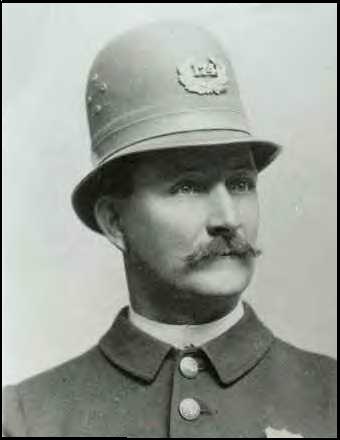

Portrait of a Baltimore Police Officer 1879 wearing 2nd. issue badge

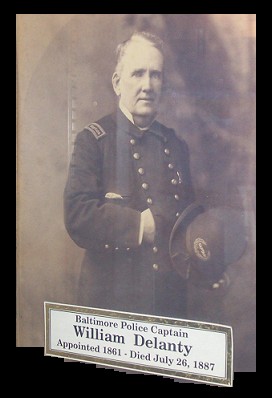

Captain William Delanty

Appointed: 1861

Died: 1887

Photo courtesy Sue Whittington

Patrolman Thomas Marshall Baldwin

Baltimore City Policeman

Photo courtesy Sue Whittington

Patrolman Thomas Marshall Baldwin

Baltimore City Policeman

October 6, 1873

Obit: Death of a Police Officer.-- Policeman Thomas Baldwin died yesterday morning, at five o'clock at his residence, No. 289 North Dallas Street. He was a native of Prince George County, Md., and had been on the police force of Baltimore for the past three years, where he was regarded as one of the best officers on the force. He had been severely injured on the night of the 27th. of July last, while conveying Patrick Shane, charged with stoning a house at the corner of Front and Hillen Streets, to the Middle Police Station. Shane was afterwards committed to jail for court by Justice McCaffery, but was subsequently released on bail. Patrolman Baldwin was confined to his house for some weeks after receiving his injuries. For the past month he has been on duty, although complaining at times until a week ago when he was attacked with a severe cold and had been confined to his house up to the time of his death. His funeral will take place this morning at half past eight o'clock. The body accompanied by a detachment of the police force, will be conveyed to Collington Station on the Baltimore and Potomac railroad near where the family reside. He leaves a wife and two children in the city.

Photo courtesy Sue Whittington

Patrolman Thomas Marshall Baldwin

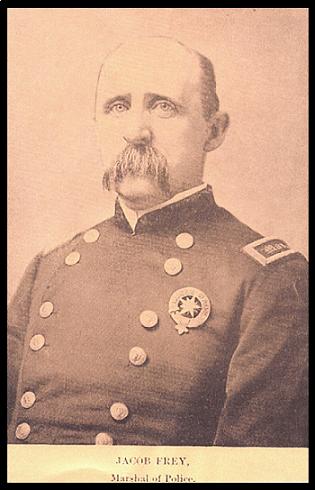

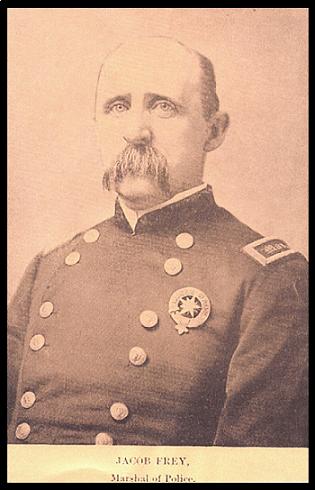

Marshal Jacob FreyWas Awarded the Departments 1st Medal of Honor

Marshal Jacob FreyWas Awarded the Departments 1st Medal of Honor

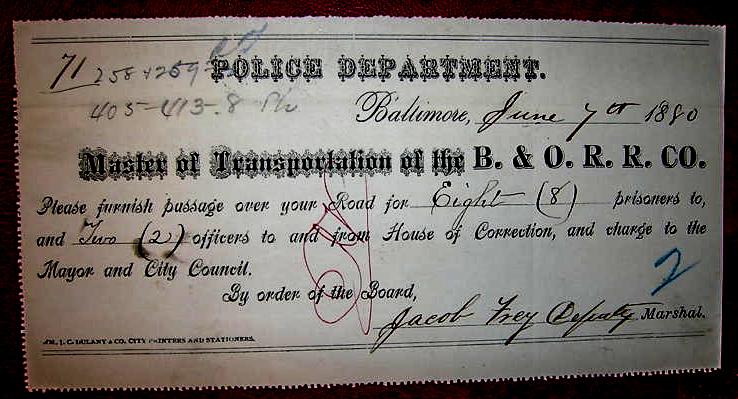

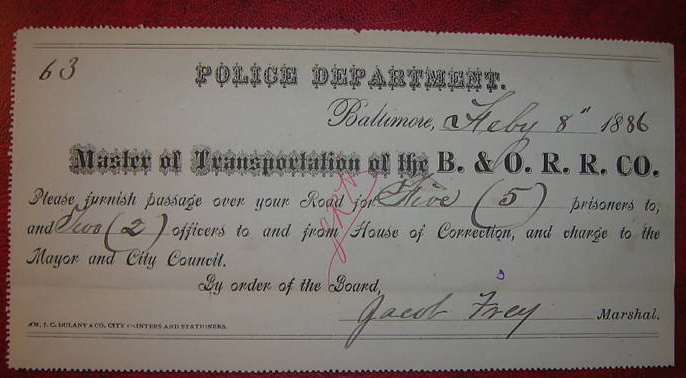

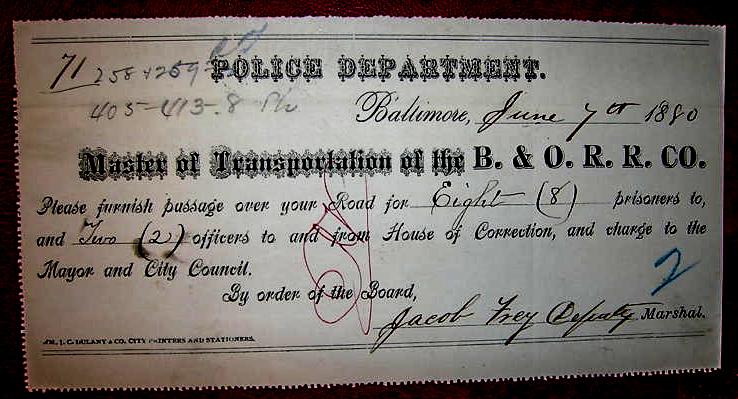

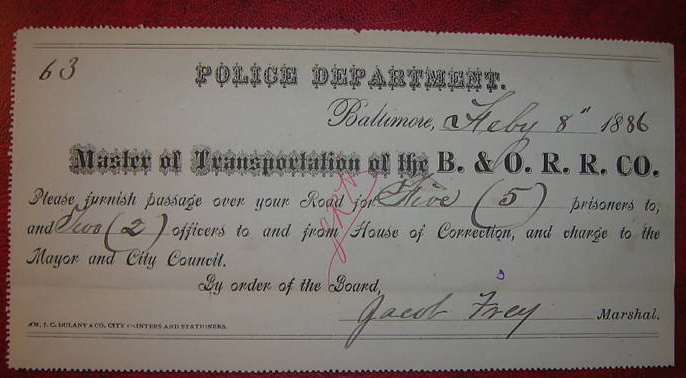

Courtesy Ret Det Kenny DriscollSigned 1880 by "Deputy" Marshal Jacob Frey

Courtesy Ret Det Kenny DriscollSigned 1880 by "Deputy" Marshal Jacob Frey Courtesy Ret Det Kenny Driscoll Signed 1886 by "Marshal" Jacob Frey

Courtesy Ret Det Kenny Driscoll Signed 1886 by "Marshal" Jacob Frey

February 19, 1878

The Police force of Baltimore,

Baltimore Sun,

There is scarcely a citizen in the city of Baltimore having the best interest of said community at heart, who shall become familiar with the provisions of the bill now before the House of Delegates to modify the hours of service of a police force, and to authorize them to appear in citizen dress when off duty, that will not be surprised that such a measure is proposed over the heads of the commissioners. The first duty of the Gen. assembly is to preserve all parts of our judiciary system from the devices of demagogues and an efficient police force lies at the very root of that system. What is known as the Matthews bill directly interferes with the whole present discipline of the force, upsets, indeed, the labor of years and the advantages derived from it. The bill undertakes to regulate the hours of service, instead of leaving that and all such details to those who have the responsibility of administration. It describes an eight hour system to the force as a permanent thing: that is to say, eight hours of duty in uniform as a policeman, and 16 hours off-duty, during which, as if more effectually to remove the wholesome influence of discipline, the men may throw off their uniforms and appear without the least insignia of their honorable calling in the citizens dress. There could scarcely have been a better plan devised for demoralizing the force.

As for the hours of duty they are already regulated with due regard to the comfort of the men and the welfare of the service. None of the officers of the force, many of whom have worked themselves up through the ranks, ask for the changes that are contemplated by the bill: nor do the best man in the force indicate a desire for them, for they foresee as any one may that 16 hours of leisure every day in the citizens dress might lead to nonsense on the part of some of the men and so bring the entire force into disrepute.

Police duty. It is true is more or less hazardous and is some respect onerous, but it is one that has always been sought, and is not shunned.

"I Doubt less than the largest majority of men now on the force have proper ideas as to what they are paid for. The pay is not simply for the service performed within certain hours, but having been chosen from the mass of their fellow citizens as conservatories of the peace, they feel and recognize the duty of setting an example of discipline and good conduct at all times, and would not wish to see any system introduced that would lessen respect for, or impair the efficiency of the body they belong to, either on or off duty."

It is difficult to divine the object of this proposed change in the police law unless it is a political one, the seeking of personal advantage at the expense of the community. If there be at least ground for this suspicious. It is quite enough to condemn the bill, apart from the direct injury, it would afflict on the force. The rules regulating hours of police duty at present, as prescribed by the board, are the result of experience and work very sufficiently for all concerned, serving at the same time the proper interest of the public.

The force is ordinary, divided into Sections A, and Section B, the time of duty of Section A numbering 160 men is from 6 AM to 7 PM and of Section B numbering 340 men is from 7 PM to 6 AM, but the force from about 6 January until the severe weather is over is divided into three unequal sections as follows.

Section A 121 men from 7 AM to 6 PM

Section B 223 men from 6 PM to 2 AM and

Section C 156 men from 1 1/2 a.m. to 7 AM

During the winter when the Christmas holidays are over, there is less disorder then at other seasons of the year and the short system is consequently adopted at that time because it can be without danger to the community, and with benefit to the men who shorter hours shield them from to prolonged exposure to the inclement weather. If the short system called for by the Matthews Bill were permanently introduced an increase of police force would be called for to meet it. Consequently, an additional expenditure of money for police purposes. Again, if the force or worked on this shorter system, the result would be that the pay would have to be put on the short system also, as to make up the numerical strength called for without increasing the aggregate the great expense of the force. It stands to reason that if the work of the police force is to be reduced by at least one third The corresponding reduction of pay must follow for the commonality while willing to bear the present aggregate cost of policing the city, have no idea of augmenting that burden, and it is not at all necessary to do so, as every man of honesty and common sense will be aware

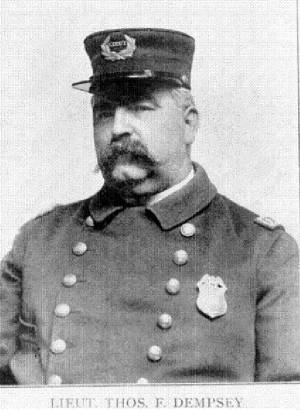

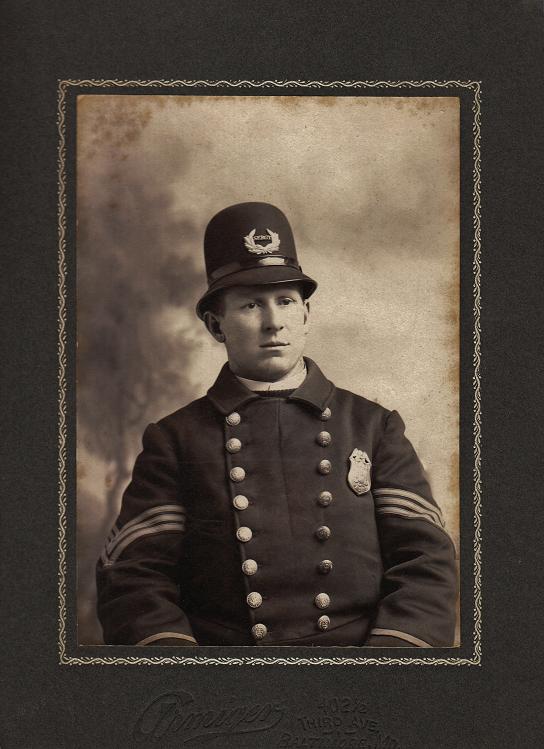

Baltimore patrolman wearing 3rd. issue badge

James William Conner was born 7 September 1839. He was a Baltimore City police officer from 1868 until 1870. This photo was taken about 1868 and shows his police uniform. The child is possibly his son William Conner. James W. Conner served in the 3rd Artillery CSA from January through November 1862 when he was wounded and mustered out. In 1870, he and other Confederate veterans were dismissed from the police force without cause. James W. Conner died 2 January 1906.

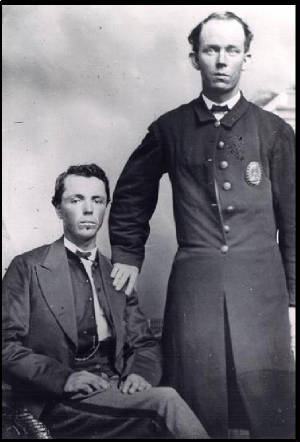

Police Officer Calvin Sunstrom (standing)

May 3, 1870

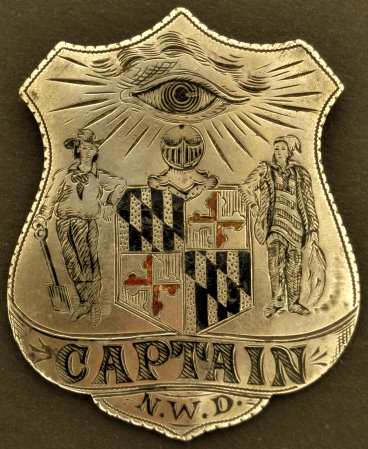

The MD emblem 1st appeared on the Captains badge in 1886 after Marshal Frey re-designed the badge for our Captains and made the Ever on the Watch - or - All Seeing - "Eye" Badge. So it would only make sense that this hat and device came along sometime after then. If we look at the above pic 2nd row 3rd in we'll see a hat similar to this being worn by what appears to be a Lieutenant

The Below article appeared in the Adams Sentinel Newspaper in Gettysburg Pennsylvania.

Sgt. William Jourden Shot

October 19, 1857

Election in Baltimore,

On Wednesday last, an election took Place in Baltimore for members of the City Council, and it appears to have been a scene of lawlessness, riots and bloodshed,On the matter a. mere mockery of the elective franchise. The democrats, it would appear, wore excluded from the polls In two or three wards, and the democratic candidates retired. There were several bloody conflicts; but in the 5th and 8th wards, the riot was the greatest. A Sergeant of the Police, Wm Jourdan, was shot dead, and several others seriously wounded. A number of arrests were made; but riot, outrage, bloodshed and marked the whole day and night—the details of which are painful to read. The vote, of course, was small, only amounting to 14,667, while at the last election 26,771 were polled—being a falling off of 12,104. The American candidates received 11,878, and the democratic only 2,789. All the Americans were elected but one, so that the Council stands 19 to 1.

Posted in the THE COMPILER, another newspaper in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

29 November 1858

Two hung for murder of a Police Officer in Baltimore, Gambrill and Ford have both been sentenced to-be hung in "Baltimore; for the murder of police officers.

Baltimore Patrolman wearing the 3rd. issued badge

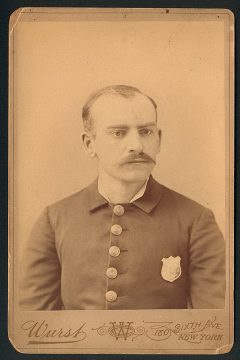

Pictured above is Michael Brooks wearing a 3rd. issue badge

Pictured below is John Edward Swift Sr. wearing the 4th. issue badge

Michael and John are Father-in-law and Son-in-law

(This information comes to us from Michael Brooks' Great-Granddaughter Rose Ireland)

POLICE DEPARTMENT

BALTIMORE, MARYLAND

November 17, 1876

Sergeant Seibold, in company with Officer John Connery, of the Northwestern district, on November 17, 1876, arrested William Jennis, colored, alias Brooks, alias Joe Russell, a notorious burglar and sneak, who was charged with burglariously entering the dwellings of Mr. P. E. Kent, No. 85 North Carey Street; Mr. Moses Kahn, No. 266 West Fayette Street; H. R. Williar North Carey Street and others, and stealing money, silverware, jewelry, clothing, etc. He was tried and convicted in Criminal Court of Baltimore and sentenced to the penitentiary for six years, from January 27, 1877. Jennis was arrested also February 20, 1874, for robbing the dwelling of Mr. George W. Flack, No. 142 Mulberry Street. He then gave the name Joseph Russel. He was sent to the penitentiary for one year. This man worked alone, and invariably entered a dwelling house from the rear by climbing sheds, porches or lattice work to second story window, while the family was below at supper. He always used the old fashioned blue head sulphur matches, which were found plentifully strewn about the floors, in the bureau drawers, etc. His work was frequently identified by the matches. About six months after his last release from prison, he went to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and robbed several houses there. He was caught, tried, and sent to Cherry Hill prison twelve years.

Police Officer James Holden 1890's

Photo from Clinton McCabe's" History of the Baltimore Police Department, 1774-1907"

Thomas P. O’Donnell, born June 1, 1866 in Birmingham, England.

He was appointed a Baltimore policeman January 24, 1890, and made detective four years later.

One of his most famous cases was the capture of a murderer and Post office robber. The post office at White Plains, N.Y., had been held up and Postmaster Walter B. Adams, a personal friend of then Governor Theodore Roosevelt, had been killed. Police were seeking Eddie Jacks, alias Peter James, for the crime. Thomas O’Donnell, then a rookie detective, got a tip that the fugitive had just slipped into Baltimore and was staying at a boarding house on St. Paul St. Anxious not to let his man get away, the young officer dressed in overalls borrowed a bicycle from Detective Captain Solomon Freeburger and hot-pedaled to the boarding house. He said he had heard the new boarder was a bicycle repairman, so he asked for the fugitive under the pretext of wanting a bicycle lantern repaired. Det. O’Donnell had put two pistols in his coat pockets before calling on the fugitive. As he sat down beside the suspect in a drawing-room, Detective O’Donnell edged up beside him and felt a pistol in his pocket. When the bandit saw one of the gun barrels protruding from the Detective's pocket, James leaped up with not one but two pistols in his hands. At the same moment, Captain Freeburger and a Philadelphia detective burst in and overpowered him. It was believed that the desperado was also planning to rob Mr. Poultney, in the building next door. For the capture of the post office robber he was commended by the late Mayor Malster, and then Governor Roosevelt in person presented a $1000 reward to him for the capture.

In addition to receiving the reward and congratulations from Governor Roosevelt, Detective O’Donnell was given a “Roll-Of-Honor Medal,” the department’s highest award, for the action. At that time–when he had been on the force twelve years–Detective O’Donnell had an imposing record. In his career, he was shot at only once and that was in a gun battle with two burglars in the basement of a cigar factory on Paca street near Cider alley. He trailed two Negroes into the basement and in the darkness, a pistol battle ensued, reinforcement officers arrived in time and the burglars were arrested. Lieutenant O’Donnell was unharmed.

Seventy years old, he retired after forty-eight years of continuous service, 1890-1938, during which he was commended a total of thirty-five times. On his last day he left the Detective Bureau early for his home located 2003 Boone street, where he lives with his wife and daughter. “I’m still active,” he said, as he departed. “I can’t loaf and I’ve got to do something. Guess I’ll try to get me a job as a private detective now.” St. Ignatius Church, on Calvert street has an annual novena and “Tom” O’Donnell is on the job today, every day, just as he has been for 35 years or more, or ever since the novenas were inaugurated by the late Rev. F. X. Brady.

Det. Lieutenant O’Donnell, for half a century a member of the Police Department, and for much of that time one of its best detectives, is retired from active service, so far as his police duties are concerned. But, he is still on duty, night and day, at the church while the novena is being held.

The story is that when the late Father Brady inaugurated the novena, he applied at the Police Department and asked that a tall, slender young man, Thomas P. O’Donnell, whom he knew, be assigned to duty during the special services. The request was granted and so “Tom” has been going back year after year. His colorful career in the Police Department extended over a period of 48 years, in which time he arrested murderers, kidnappers and – in the earlier years – horse thieves. He retired as a detective lieutenant in 1938, the possessor of 35 commendations Lieutenant O’Donnell has been ill approximately a week prior to his death on March 21, 1947

Data compiled by great-niece Sister Anne M. O'Donnell. from Baltimore Evening Sun, April 14, 1938; Baltimore News-Post, Evening, March 9, 1939; Baltimore Sun, March 22, 1947. Photo from Clinton McCabe. History of the Baltimore Police Department, 1774-1907. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Board of Police Commissioners, 1909. Enoch Pratt Central Library.

Photo courtesy Pat Pilling

Sergeant Frank Gatch

1890-1915

Born:July 5, 1849 Died:January 7, 1917

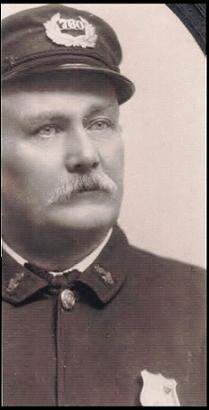

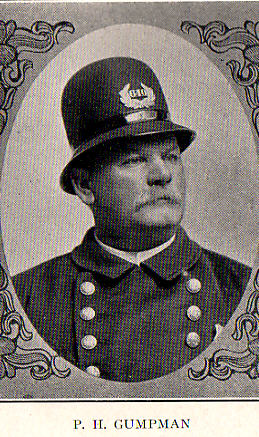

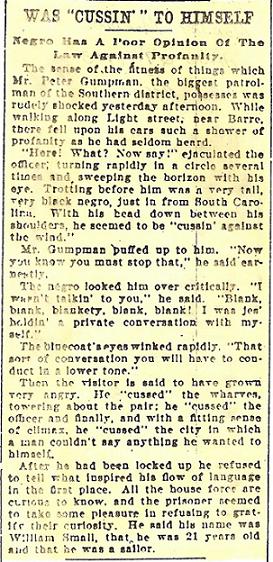

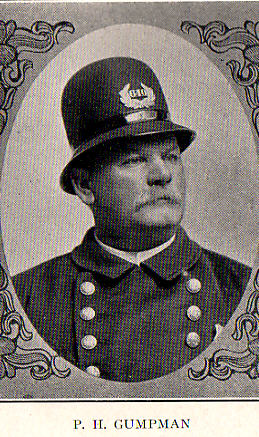

Peter H. Gumpman appointed to Police Force 1886 and assigned to the Southern District for 30 years.

Baltimore SUN paper Monday Morning,

April 27, 1903 page 12.

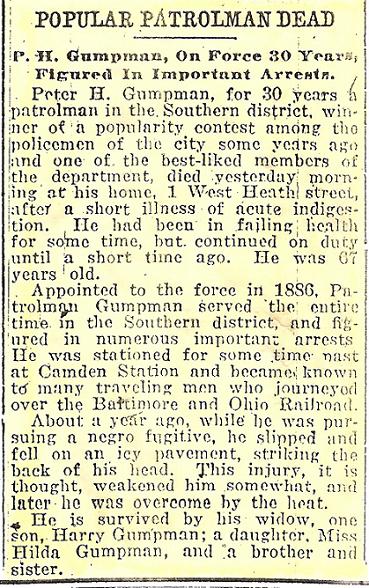

Baltimore SUN paper Monday morning

January 8, 1917 page 3

Baltimore SUN paper Tuesday morning

January 9, 1917 page 6

Officer John William Garmer

Served with the Baltimore City Police

1899-1925

Great-Grandfather of Retired Officer William John Garmer Southern District

Police Officer Howard Swope

Southwest District

Another Reorganization of the Department

History Baltimore Police Department

1774 – 1907

This measure was made an act on February 2, 1860 provided that while the city Council of Baltimore might pass ordinances for preserving order, securing property and persons from violence, danger and destruction, and for promoting the great interest and insuring the good government of the city, it could pass no ordinances which would in any manner obstruct hinder or interfere with the board of police commissioners or any officer under them. All of the Mayor’s powers, conferred by preceding legislation, were repealed. Four members of the board of police commissioners were authorized to be appointed, and the mayor was to be ex officio member of the board.

The first Commissioners appointed under the new act were Messrs. Charles Howard, William H. Getchell, Charles D. Hinks and John W. Davis, two of whom were to serve for two years and two for four years, the duration of their office to be decided by drawing lots.

The duties of the board of commissioners were, in general, “to be at all times, day and night, within the boundaries of the city of Baltimore, as well on water as on land, to preserve the public peace, prevent crime and arrest offenders, protect the rights of persons and property, guard the public health, preserve order at elections and at all public meetings and places and on all public occasions, prevent and remove nuisances in all streets, highways, waters and other places; provide a proper police force at all fires for the protection of the firemen and property; protect strangers, emigrants and travelers at steamboat landings and railway stations; see that all laws relating to elections, the observance of Sunday, and regarding pawnbrokers, gambling, intemperance, lotteries, policy, vagrants, disorderly persons, slaves and free Negroes, and all the public health ordinances were enforced, and also all the ordinances of the Mayor and city Council, provided these be not inconsistent with the provisions of the act or any law of the state which may be made enforceable by a police force.”

The newly created board of police commissioners were authorized to “appoint, equip and arm a permanent police force, the number, exclusive of officers to be 350.” They were also empowered to reduce or increase this force, but could not increase it to more than 450.

No individual could be employed as a policeman who had been convicted of a crime or against whom any indictment was pending for an offense, the penalty for which was imprisonment in the penitentiary.

Policemen were appointed for five years and could only be removed for just cause and after a hearing before the board of commissioners.

In 1862 the military signified its willingness to turn over the Police Department to the civil authorities, from whom they had torn it. The Legislature was at that time in sympathy with the Federal Government. The former police law of 1860 was repealed, but its provisions were practically re-enacted with the difference that the number of Police Commissioners was fixed at two. John Lee Chapman, Mayor of Baltimore, was made an ex-officio member of the Board and Messrs. Samuel Hindes and Nicholas L. Wood were appointed Commissioners. This Board of Commissioners qualified on March 6, 1862, and the oath of fealty to the government was required of them and their subordinates. On March 10 the Board entered upon its duties. The force was entirely reorganized and W. A. Van Nostrand was appointed Marshal. Marshal Van Nostrand went into office when Baltimore was probably one of the most troublous cities in the North. Sectional feeling ran high and there were constant conflicts of opinions between Northern and Southern partisans. The Deputy Marshal was William H. Lyons. Marshal Van Nostrand, besides having charge of the Baltimore Police Department, was United States Provost Marshal of West Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania and New Jersey. During the greater part of Marshal Van Nostrand's incumbency barricades were established throughout the city, through which no one was allowed to pass after nightfall without a pass. The military and police acted in concert, and while martial law was threatened on a number of occasions, it was never declared, and the courts and magistrates exercised their regular official functions. On March 17, 1864, Marshal Van Nostrand was succeeded in office by Thomas A. Carmichael, and John S. Manly was appointed Deputy Marshal. Marshal Carmichael served until 1867, when a new Board of Commissioners was appointed. Commissioners Nicholas L. Wood and Samuel Hindes continued in office until 1866, when they were removed and Messrs. William T. Valiant and James Young were appointed Commissioners. Messrs. Hindes and Wood refused to deliver to the new Commissioners the police establishment and continued for some time to exercise control over the Police Department. The new Commissioners established their headquarters at another point and began preparing to exercise their official functions. Measures were taken against them in the Criminal Court and they were arrested on the charge of conspiring to obtain possession of the Department. The Commissioners refused to give bail and were imprisoned in the City Jail. They were released by Judge Barton and a few days later took possession of their office and entered upon the performance of their duties. Marshal Carmichael surrendered his command and Commissioners Valiant and Young immediately appointed Col. John T. Farlow Marshal of Police. Capt. John T. Gray, of the Central District, was appointed Deputy Marshal. Marshal Farlow was appointed on April 22, 1867, and served until April 17, 1870, when he resigned. On March 15, 1867, the new Board of the Police Department was organized under the State law. Messrs. Lefevre Jarrett, James E. Carr and William H. B. Fusselbaugh were elected Commissioners by the Legislature. Commissioner Lefevre Jarrett died on February 25, 1870, and the Legislature, then in session, elected Mr. John W. Davis to fill Mr. Jarrett's unexpired first term. Mr. Thomas W. Morse was elected to fill Mr. Jarrett's unexpired second term, and on March 15, 1871, he took his seat, succeeding Mr. Davis. Mr. Morse served four years. In April, 1867, Marshal Farlow retired and Deputy Marshal John T. Gray succeeded him. Capt. Jacob Frey, of the Southern District, was promoted to the office of Deputy Marshal. In 1872 the State Legislature made several important changes in the police law, particularly in regard to the terms of service of the Commissioners. Under the new law Mr. John Milroy and Col. Harry Gilmor were appointed members of the Board. The Board at that time consisted of Colonel Gilmor and Commissioners James E. Carr and Milroy. In 1877 Mr. Milroy retired and Gen. James R. Herbert was elected to succeed him. The riots of 1877 were a setback, in a police and business way, to Baltimore, then rapidly becoming in the matter of good order and commercial prosperity the leading city of the South. The history of the trouble between the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and its employees has been written fully by historians more competent to deal with this subject, so we will confine ourselves to trying to tell how the members of the Baltimore Police Department distinguished themselves during the stirring days of July, 1877, and will be as brief as possible, considering the importance of the subject. On July 16, 1877, the strike was declared at Cumberland. By noon it had reached Martinsburg, W. Va., and the militia were called out. The police, anticipating trouble, had prepared for it. On the day following the excitement began. A freight train of eighteen loaded cars bound for Locust Point was partially wrecked by means of a misplaced switch near the foot of Leadenhall Street, Spring Gardens. That night the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad employes held a meeting and decided to support the strikers. At 3 o'clock on the afternoon of the Friday following Governor Carroll held a consultation with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad officials and an order was issued for the First Brigade, M. N. G., to repair to Cumberland. At 5.45 o'clock that evening the military call, "1 - 5 - 1,” was sounded by the City Hall and fire bells. The people knew what the call meant, and in a short time the streets around the armories were filled with crowds of strike sympathizers. In front of the Sixth Regiment Armory, Fayette and Front Streets, a large crowd had gathered. The officers of the regiment saw the menacing concourse and sent word to Police Headquarters asking that policemen be sent to protect them along the line of march to Camden Station. Their request was promptly responded to. At 7 o'clock P. M. a brick was thrown through one of the windows of the armory. Four policemen, Officers Whiteley, Jamison, Oliver and Roberts, were stationed at the door of the armory, and when the rioters charged the doors the faithful policemen manfully repulsed them. By 8.15 o'clock the crowd became more menacing. The militia had orders to march to Camden Station and prepared for trouble. The first attempt of the soldiery to leave the building was received with such an outburst of groans, hisses and stones that they retired. The next time they came out they had orders to fire if molested. The first company fired high, but the attack became so serious that the following companies aimed their weapons at the crowd and discharged them. From then until Camden Station was reached the firing was general; a dozen people were killed and scores wounded. Soon after the regiment reached the building the station was set on fire. Firemen appeared to extinguish it, but were set upon by the rioters and would have been not the police rushed to their rescue and beaten back the crowd. The soldiers appeared to incense the mob, while the police awed it. A scanty handful, compared to the throngs that surrounded them driven from the scene had they charged and charged again to protect the armed soldiers from injury. On Saturday crowds again collected around the station, and a fire alarm so excited the rioters that they rushed toward the lines formed by the police. Deputy Marshal Jacob Frey called to his comparatively few men to "stand steady" and gave the command "Draw your revolvers." Several shots were fired from the crowd and four policemen fell wounded. At this the Deputy Marshal gave the order, "Fire, and aim low." The command was obeyed, and as the policemen fired they rushed forward and each officer seized a prisoner. In all fifty arrests were made, eight men were killed and a number wounded. At 11 P. M. of the same date there was another outbreak and more arrests were made. The next morning (Sunday) the mob again collected around the station, but the surrounding streets were cleared by the police. When the riot had assumed such threatening proportions that the police and local militia were unable to cope with it United States troops from New York and other points were hurried to Baltimore and two war vessels, with decks cleared and ready for action, anchored in the Patapsco. The Board of Police Commissioners swore in several hundred special officers, among whom were Baltimore's most prominent citizens. Messrs. C. Morton Stewart, Alex-

The first powered boat in the Baltimore Police Harbor Patrol came in 1891 – and was The Lannan, followed in 1928 – by The George G. Henry, then in 1940 – came The Charles D. Gaither, and then in

1946 – came the The Beverly Ober.

THE HARBOR POLICE

History Baltimore Police Department

1774 – 1907

pages 144-146

Nearly everyone who patronizes the summer excursion boats and the score of passenger boats that enter and leave Baltimore harbor is familiar with the sight of a trim looking little dark-hulled steamer that makes her way in and out of the tangle of shipping, skirting around wharves, running into tortuous docks, darting around the ships and steamships that lie at anchor at the wharves or in the regular anchorages. Sometimes at night the passengers on incoming and outgoing steamers catch a glimpse of a dark hull close aboard them and then a glare from a searchlight is sent across their decks and searches the wharves that line both sides of the river front. The little steamer is the harbor police cruiser "Lannan," named in honor of former Deputy Marshal John Lannan, deceased, who had charge of her construction. The Lannan was built in 1891 by James Clark & Co., from plans kindly loaned the Department by the United States Government. The harbor patrol boat was completed on August 10, 1891, and after a very successful trial trip was accepted and immediately put into commission. The steamer is sixty feet long overall and has thirteen feet beam. She draws about six feet of water and has seventy-five indicated horse power.

Prior to the launching of the Lannan the harbor was patrolled by policemen in rowboats, but, as it can be very readily understood, this plan proved utterly inadequate to the police needs of nearly ten miles of water front. Since the time she was launched the Lannan has been continuously in service, save when she was on the ways for necessary repairs. In touring the harbor the Lannan averages nearly fifty miles per day, and as she has been almost steadily on the move since the day she was launched, she has, on a conservative estimate, traveled about 127,750 miles, a distance nearly six times the circumference of the globe. Prior to the launching of the Lannan the vessels in the harbor and the warehouses along and around the wharves were nightly attacked by thieves who operated from the river. Frequently the captains of small vessels would go ashore to return and find that their craft had been stripped of everything movable, including cordage and sails. The commissioning of the police cruiser practically put an end to this extensive thievery, and the fact that she was equipped with a powerful searchlight and could train it over and under piers and on the decks of suspicious craft acted as a check to river pirates and criminals who lurked and operated along the water-front. Shortly after she was built the Lannan was equipped with a fire-fighting plant, and the latter has been used to great effect in fighting fires in the warehouses and along the wharves where the steamer has her regular patrol.

The Lannan is also used for the recovery of the bodies of persons who are drowned in the harbor, and frequently she is called upon to go to distant points in the Chesapeake on the same mission. Her crew is trained in the expert use of the grappling irons and hooks with which the bodies of drowned men and women are fished from the river bed, and the deck of the little steamer has carried many a pitiful canvas covered burden, the earthly remains of some unfortunate who accidentally fell into the water or purposely sought death and oblivion in the murky waters of the harbor.

In the summer of 1906 the Board of Police Commissioners purchased a gasoline launch to act as an auxiliary to the Lannan. This boat was rebuilt and remodeled recently and was launched on May 4, 1907, when she was christened the Farnan, in honor of Marshal Thomas F. Farnan, who on April 30, 1907, completed forty years' continuous service as a member of the Baltimore Police Department. During the warm months the Farnan will patrol the harbor instead of the Lannan, which will be kept at the Harbor Police Headquarters, Philpot and Thames streets. Thus the Department will have two thoroughly able boats at its command should an emergency occur where the services of both the Lannan and the Farnan might be called upon. The members of the Harbor Police Force, who are commanded by Lieutenants Albert L. League and Edward J. Carey, are: Patrolmen John B. Dorsey, Milton Harrington and John J. Ryan. Thomas E. Perry is chief engineer and Charles H. Aborn, assistant engineer. Richard Murphy

is fireman and Richard Stanton, assistant fireman.

In the last report of the harbor police service made to the Maryland General Assembly of 1905 it was shown that during the year 1904 property valued at $13,257.46 was saved and recovered by the harbor police and during the year 1905 the property saved and recovered amounted to $7,616.41. From this a small idea can be gained of the work accomplished by the police who guard the harbor and the docks, warehouses and business concerns that hem it.

Excerpts from - Proceeding of City Council 11 Dec 1856

(During this December 11th session in 1856) Mr. Boyd moved to strike out all of the section providing for arming the police with revolvers and other suitable weapons AND placing muskets at the station-houses. Mr. Boyd said the cost of arming the police with revolvers would alone amount to $516l; that there were men in the police not fitted to trust with arms, and if the amendment was not adopted he feared he should be compelled to vote it was necessary to arm the police, as long as rowdies were armed with revolvers and other weapons. In New York and Philadelphia where there is a penalty for carrying concealed weapons, the police are armed by the city authorities. The muskets at the stations houses were to be kept there under the charge of the Mayor, to be used only in case of riot, where such arms were necessary to compete with armed mobs Mr. Boyd replied that only a few weeks since one of the police had drawn his revolver at Carroll Hall on one of the night police - He reiterated that there were men not fit to be trusted with such arms. The time was when twenty-six men kept this city quiet and in good order without being armed. As to giving the police muskets, we might as well have a standing army. If muskets are necessary at any time, the military are always ready to obey any call of the Mayor. Mr. Pinkney again urged that it was necessary to arm the police - you must arm them to have any effect at all. If the military were called out at the present state of feeling in the public mind, instead of preventing, or suppressing riot, it would lead to one of the bloodiest riots on record. Mr. Howard opposed the amendment - he believed that it was necessary to arm the police in order to protect the citizens - to put down the riots that had so often of late violated the law and shot down peaceable persons. We may have seen outrages heretofore, but we have not seen orderly citizens shot down at their own doors - men driven from the polls when only seeking their right of exercising the elective franchise – polls obstructed and men leading on armed mobs with apparent impunity - Mr. Boyd was willing to judge the present by the past - If we are to have no better men on the police than for time past, he was not willing to place arms in their hands. If the police are armed, no man is safe in this community. The question being taken on Mr. Boyd's proposed amendment, it was rejected by yeas 3, (Messrs. Boyd, Tidy, and Carroll,) and nays 16. Mr. Nalls moved to strike out that portion of the ordinance placing muskets at the station houses rejected by yeas 6, (Messr Daiger, Boyd, Green, Tidy, Carroll and Nalls,) and nays 13. Section 8 was reconsidered, on motion of Mr. Handy, who moved to amend it by making the police officers to be confirmed by the City Council, as other city officers are; which was adopted with but one dissenting voice.

In short, Mr. Boyd’s amendments were struck, and the bill allowing the city to arm police was passed.

During the times the city was nearly taken over by several gangs involved in politics, they would travel the various wards making it nearly impossible for honest voters to vote. As such elections were not fair, the same people won every time. I wouldn't be surprised to hear Mr. Boyd was benefiting more by having the Know Nothings, Plug Ugglies, Bloody Tubs, Etc. ruling the city with an unarmed, or under armed police force, at the time police carried their own weapons, usually single shot pistols, or some other small pocket pistol, ill-equipped to fight these gangs. We lost several officers at the times. Still arming police, wasn't as much to help, or protect the police, so much as it was to allow politicians to receive fair votes. It may also be worth reminding readers of the Know-Nothing Riot of 1856, in which some of the worst rioting of the Know-Nothing era in the United States, occurred in Baltimore. It was the fall of 1856, street tensions had escalated sharply over the preceding six-dozen years as neighborhood gangs, most of them operating out of local firehouses, became increasingly involved in party politics. Know-Nothing candidate Thomas Swann was elected Mayor of Baltimore in 1856 amidst violence and a heavily disputed ballot. Police Commissioner Kane was also involved in this, and in fact testified in open court for the defense in a trial against a Know Nothing that was charged with killing one of Kane’s Officers, Kane was more dedicated to his party than he was his own men. Based on what these gangs were doing, it is obvious what some politicians wouldn’t want to fight it. The point being, City Council may not have as interested in protecting their police, i.e. Officer Safety, or even Public Safety, as much as they were in getting voters to the polls. This is supported by the line in the above artcle in which Mr. Howard who was opposed the amendment said, "He believed that it was necessary to arm the police in order to protect the citizens, to put down the riots that had so often of late violated the law and shot down peaceable persons". He added, "We may have seen outrages heretofore, but we have not seen orderly citizens shot down at their own doors" Finishing off with, "Men driven from the polls when only seeking their right of exercising the elective franchise – polls obstructed and men leading on armed mobs with apparent impunity." This leads me to beleive, or at least has to make me concider much of the motive arming police, was to help getting voters to the poles, I don't have proof, and in a million years could never find such evidence, but I offer the suggestion, with the information, and hope you see what I see.

3 Aug, 1875

The Use of Firearms by the Police The shooting of a colored man Daniel Brown on Friday night by policeman McDonald, apart from the merits of the particular case, which will be the subject of judicial investigation, is calculated to direct public attention to the general question of the right of police officers to use deadly weapons in the discharge of their duty. The contingencies which require the use of such weapons are happily in this community of where an exceptional occurrence. It is only out of abundant caution that the police are required to be armed at all, or with any other weapon than the ordinary policeman’s club. The club itself all to be, and ordinarily is, but the staff and wand of office – this symbol of authority to was even the disorderly and lawless are compelled to pay obedience. It is upon this respect for law which is excited by the mere display of the external symbols of law that the preservation of society ordinarily rests. It is the badge and uniform other policeman, rather than his muscles or truncheon, which command respect and compel obedience. It is only, as we have said, in exceptional cases and in comparatively rare cases that the assertion of the authority with which he is clothed by law, and which usually makes itself felt and obeyed by moral sanction, requires for its enforcement the aid of blue force, and, above all, of deadly weapons. The law not only denies to the citizen, but punishes him in the use of concealed weapons, such as the pistol and the knife. The law arms its officers with pistols, not that they may use them rationally or indiscriminately, but in order that in extreme, but possible cases, they may not be deprived of the means of necessary self-defense, and the law may not be trampled upon or outraged in their person. In the case that happened on Friday night we, of course, desire to express no opinion as to the extent of the provocation which the officer may have had to use his club, or whether he will be justified in resorting to the pistol. These are questions for a jury here after to consider and determine. As to the rules was all to govern policeman in such cases, or finding themselves similarly situated to Officer McDonald, there can be no question. In the first place, the police force is no place for passionate or excitable men, who are able to easily lose temper, still less to the easily alarmed, and led to believe their lives in danger when no danger really exists at all. The policeman in all cases, and above all other men, all to be cool and collected, capable of the highest self-control, and not liable to lose either his temper or his head. In the next place, before using his authority, it behooves the policeman always to consider what are the limits of his authority, and what is the Association for its exercise. An attempt to commit a murder, or burglary even, presents a totally different case for violation of a city ordinance. A policeman may be justified in shooting a murderer taken red-handed in the act, or who resists and defies arrest, no policeman would be justified in killing a citizen who refused to have his sidewalk cleared of ice, or to exhibit a license for a “cakewalk” or a “pay party.” Again, all citizens of whatever color or degree, rich and poor, white and black, have the same and equal rights of personal immunity and protection before the law. Consequently the case of officer McDonald must be judged in all respects precisely as if the person whom he shot had been a white man, and with reference solely to the circumstance under which he acted, and in which, if at all, his justification must be found. At the most, it appears, a violation of the city ordinance might have been committed by the Keller people, who’s noisy and unseasonably revels officer McDonald undertook to regulate. Conceding that the case was one which not only justified, but called for the interruption of the police, the question will still remain – was McDonald justified in the use of either club or pistol? Mere impudence would not justify the use of the former, and unless his life were in danger, or he really, and with probable cause, believed it to be in danger, there was no justification for the use of the latter. These, however, are questions for the jury. What concerns the community is what the police, as well as all others, should be taught to feel that human life is a sacred thing, that the life of a citizen, be he black or white, is not to be lightly taken or sacrifice, and the circumstances are few and rare indeed in which a policeman will be tolerated in the use of a death – dealing weapon, for which circumstances, and such only, such weapon is confided to his hands. Too many cases have happened lately – fewer, perhaps, in Baltimore in proportion than elsewhere – of the brutal and lawless use by the police of the powers with which they are clothed. That, however, does not excuse the happening of a single case to the contrary. It is no comfort to the widow and children of a man killed by a police officer, if killed without justification, to be told that such cases rarely happen, and that it is only now and then that a man is shot or club to death by a policeman in mere cruelty or wantonness. We repeat, that we have no desire to prejudge the case of also McDonald, and in view of the good character which his supervisors and Associates on the force seemed to establish for him, it is but right that there should be an entire suspension of the public judgment in his behalf until a competent tribunal shall have passed upon the question of his guilt or innocence. Still, it may be permitted to observe that, if not criminal, he was undoubtedly hasty, and that the arms entrusted to the police are intended to be given to brave, cool and intelligent men only, to be used solely for the purposes of necessary self-defense, or equally necessary enforcement of the law.

Dec 14, 1885

Police and Their Uniform

Reported for the Baltimore Sun

The Sun (1837-1987); pg. 5

Dissatisfaction with the Objection to the

New System of Work and Barracks Life

[Reported for the Baltimore Sun.]