Espantoon

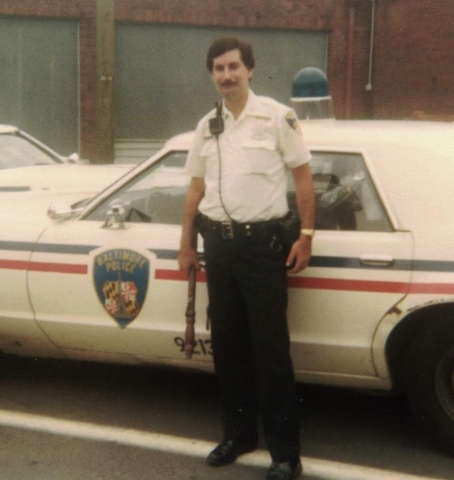

Courtesy Eli Alaman

Courtesy Eli Alaman

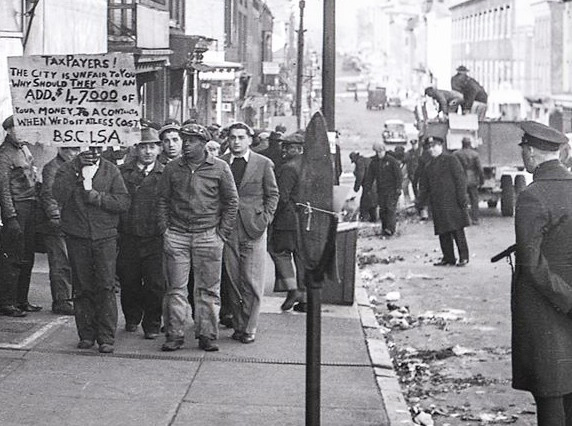

22 February 1941: Strike, Baltimore Police

Digital Painting by Ken

Espantoon

Espantoon Info/History

Webster's Third Edition: defines an espantoon as follows: "An espantoon In Baltimore, a policeman's club" We would like to start out by saying we collect nightsticks, espantoons, batons, truncheons, Billy clubs, etc. If you have one for sale or that you would like to donate, please let us know, as we are interested. For what might be obvious reasons, we particularly like the Baltimore espantoon. Aside from their being the stick carried by our brothers and sisters in law enforcement, they also show a progression not just in what we carried or had made, but in what the department had made for us and issued to us. That said, while we like Baltimore sticks, we collect all sticks from any state in the US and from any country in the world.

We have always been serious about the espantoon, and why Baltimore City Police are the only police department in the world that uses an espantoon? Also, why if a Baltimore County Officer and a Baltimore City Officer both have their sticks made by the same guy (let's say Nightstick Joe), why would one guy's stick be a baton or nightstick and the other be an Espantoon? We talked to several old-timers over the years, asking about the nomenclature of our Espantoon. We were told over and over that the part that looks like the handle at the top is actually not the handle and is called the "barrelhead." Next to that or under it is the "Thong Groove," the "Ring Stop," and the "Shaft." The word "barrelhead" might be a mispronunciation that, if correctly pronounced, may have solved this riddle much earlier, but we worked with what we had! For years, we knew the difference; we just couldn't find the words to explain it. That was, up until the night Ken read the reporter's question while reading a newspaper article one night. It was that question that flipped the switch in Ken's mind, and once it was, it was like the old saying, "It couldn't be unseen!" Now it seems we have more ways to describe or answer the question. So what was the 1970's newspaper man's question? He asked, "If a Baltimore City Officer gifts his Espantoon to a Baltimore County Officer, is it still an Espantoon?" The answer in Ken's eyes was, "No," and as odd as it may sound like so many police issues, it all comes down to training. For years, when asked what makes an Espantoon an Espantoon, the satisfactory answer was, "Webster's 3rd edition dictionary says it is!" That has not been acceptable to us, so we dug further, reading every newspaper article, every general order, and every policy. We talked to retired officers, active officers, rookies, and old timers. Doing so gave us what we think is the truest of all answers. Baltimore turns a nightstick into an Espantoon because what looks like a "handle" is the "barrelhead" (most likely originally pronounced "burlhead"), whereas everywhere else in the world the part that looks like a handle is a handle, but in Baltimore City, we turn the stick around, and that handle-looking part as the striking end. If a city and county officers traded sticks, they would each take their new stick and use it according to their departmental guidelines and training, one having a nightstick with a handle and the other having an espantoon with a barrelhead or burlhead. That is what makes a Nightstick an Espantoon.

What follows is some supporting documentation on the subject.

As for the old answer to What makes an espantoon? A name for a nightstick that is only used by the Baltimore police. Here is the old answer from that pages of Webster's 3rd edition:

![]()

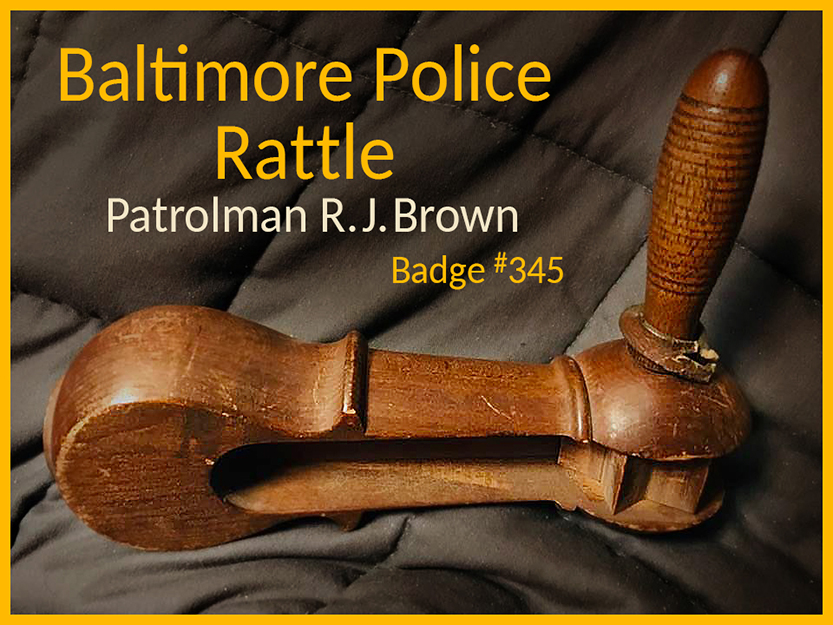

Rattles and Billy Clubs

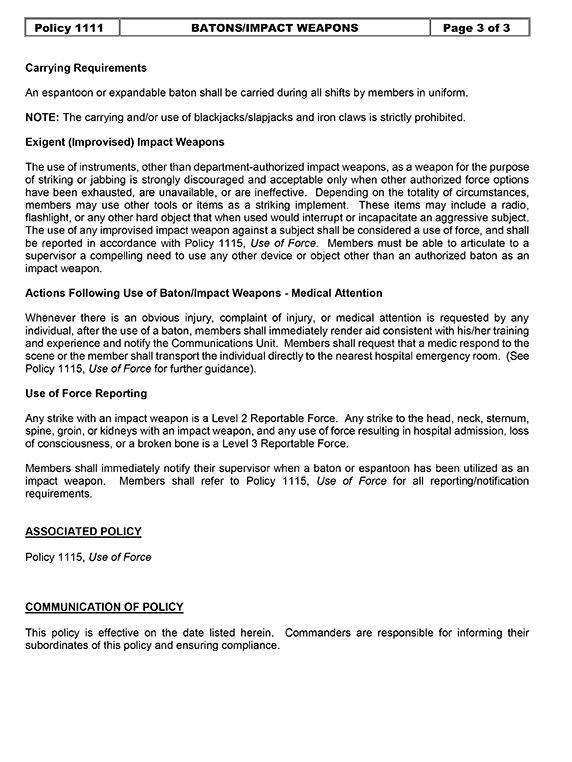

Rattle/Ratchet and a Short Spontoon

Rattle, circa 1862

These rattles were used by police and firefighters to signal coworkers. At the time, they were made by violin makers. Watchmen carried these and a short spontoon.

Rattle/Ratchet and a Short Spontoon

This daguerreotype features a bearded watchman with his wooden Rattle and a Spontoon or Club. He wore a bearskin coat, woolen gloves, and hat to protect himself from the cold nights of patrolling. He is seated next to his young son, who also wore a heavy winter coat.

This is NOT Baltimore, but the use of a Spontoon, could be a start to the origins of Espantoon, perhaps deriving from "A Spontoon" later becoming "A-Spontoon" then to one word "Aspontoon", and eventually spelled "Espantoon." There were newspaper articles with it spelled Aspontoon, Espontoon, and Espantoon.

In an 1844 Sun paper article describing the Line of Duty Death Night Watchman Alexander McIntosh, it says, “McIntosh was struck with a Spontoon, and it was later said, McIntosh lost his Spontoon." That later came to mind when he learned McIntosh was struck with a Spontoon.

Click HERE to Read Article

Click HERE to Read Article

It All Started with a Police Rattle

Click HERE to Learn More

![]()

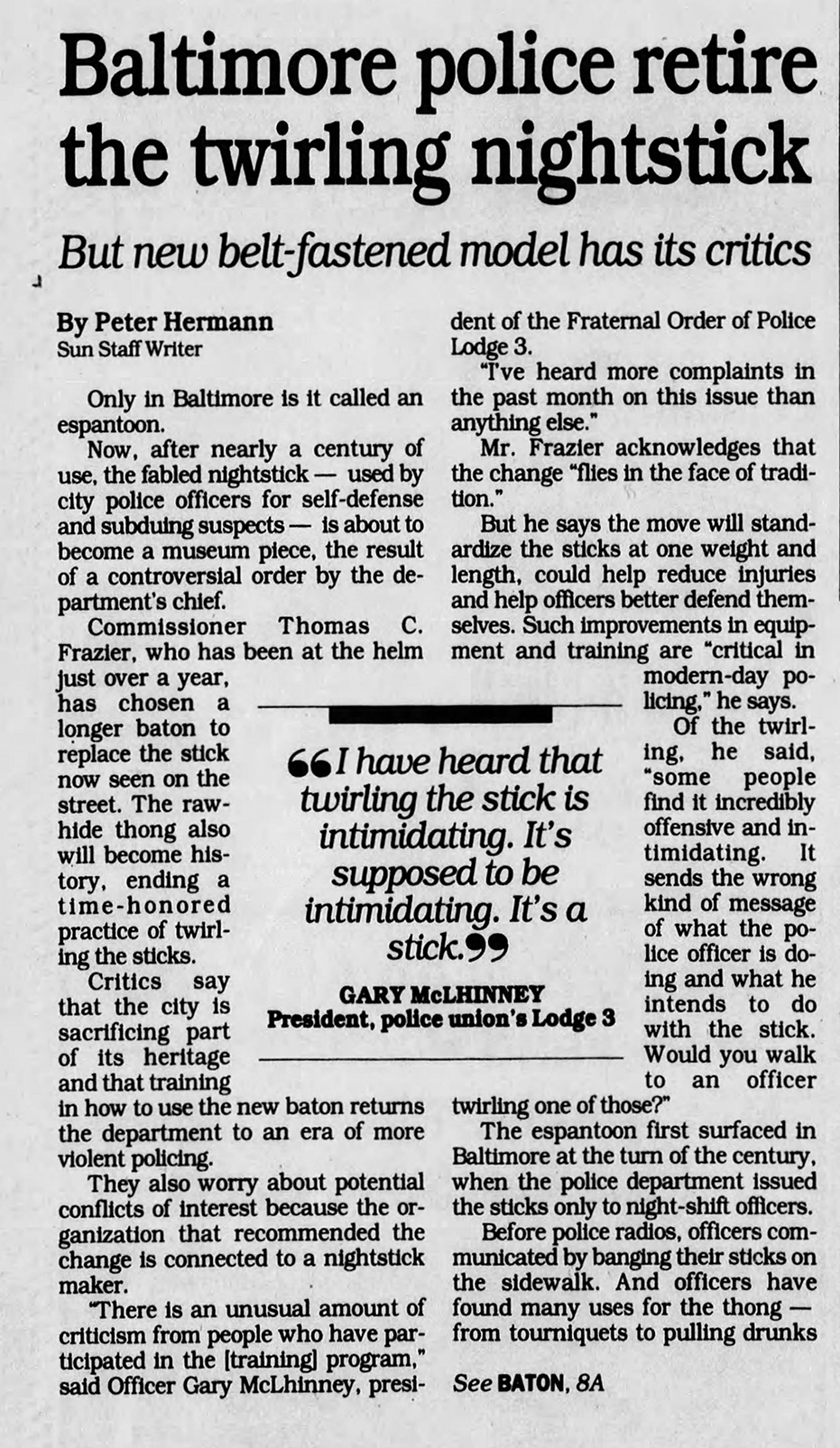

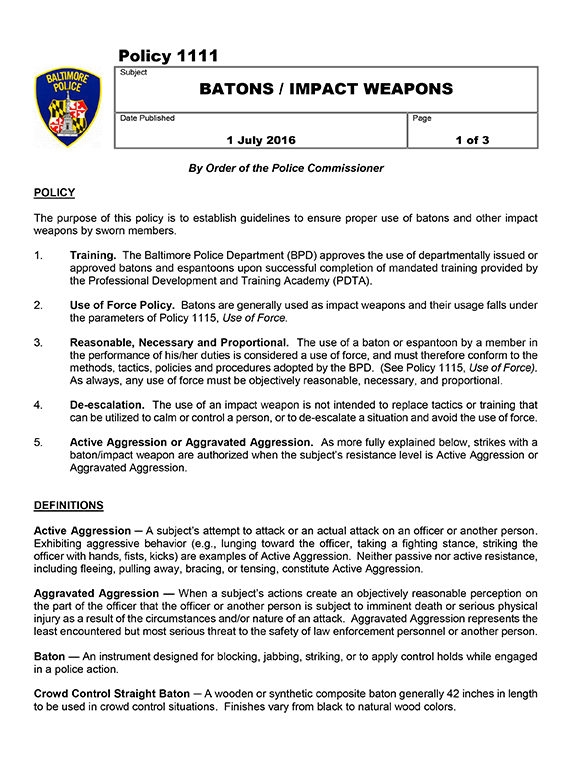

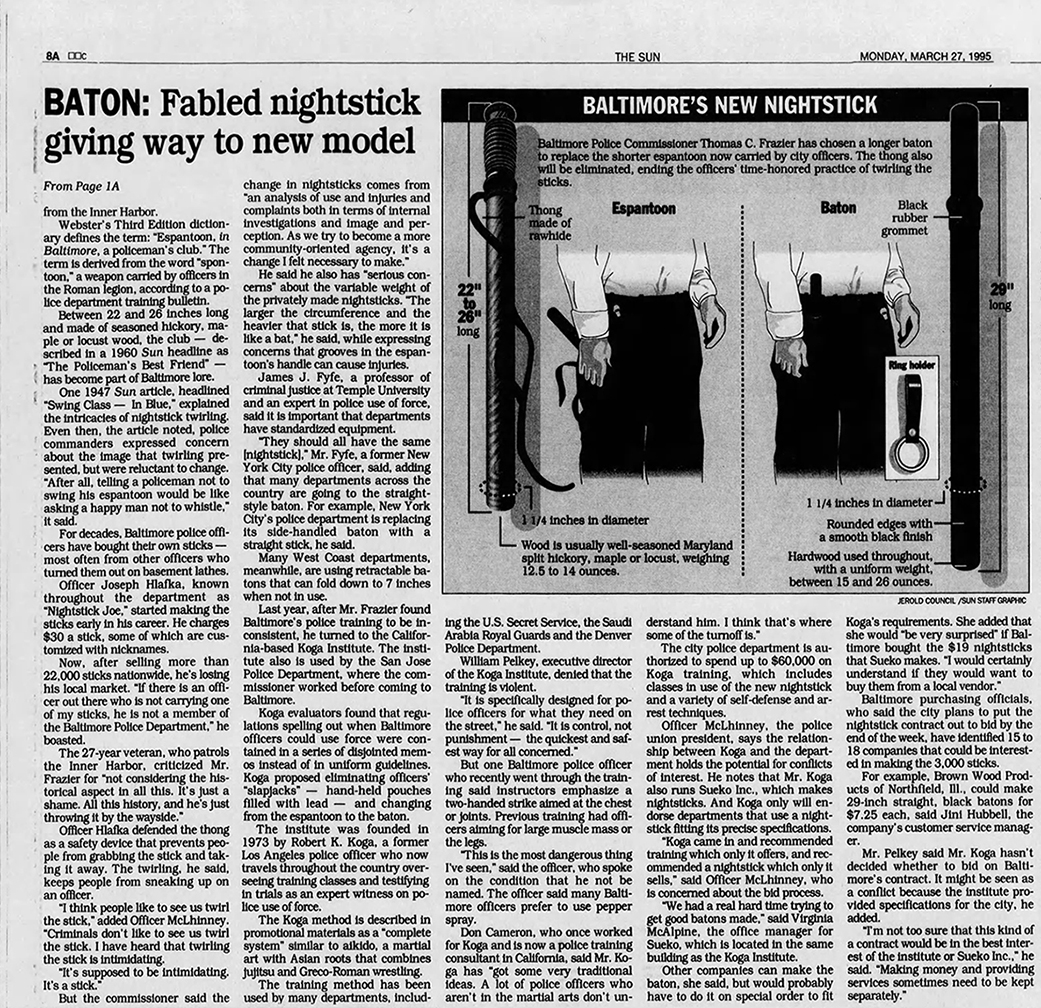

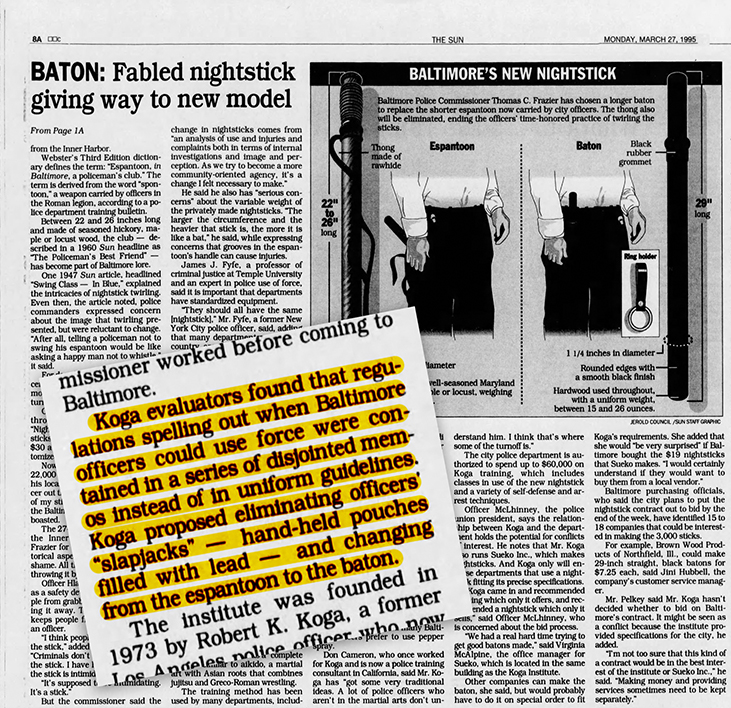

We had a difficult time explaining what made an espantoon an espantoon until reading that 1970's Sun Paper newspaper article that asked, "If a Baltimore City officer gave his espantoon to a county officer, would it still be an espantoon?" This single question sparked the answer, which we've known for years but had trouble wording our answer into a reasonable explanation. Baltimore Police Department's General Orders, or what today is known as Baltimore Police "Policy," specifically Policy number 1111, the Espantoon is defined as follows: A wooden Baton between 22-25 inches in length, with the striking end of the baton being between 1-1/2 and 1-3/4 inches in diameter and the grip end being 1-3/8 inches in diameter. This means our nightstick has a "Burlhead." But what if the county officer simply turned his baton around? Wouldn't that make it an espantoon? Well, in theory, it would, except that in Baltimore City, this can be done under Policy 1111, and remains within the officer's training; in the county, the officer would be going against his or her training, and therefore, not only would it not be an espantoon, but the officer could be charged and lose his or her job. So part of it not just that we turn it around, it, is that it is within our agencies rules and our training that we use it this way, and that is what makes our baton an espantoon.

Woodworkers that Turned Baltimore Espantoons

Woodworkers that Turned Baltimore Espantoons

1937 / 2007

1937 / 1957 – Rev W. Gibbs McKenney - Made BPD Issue - Sold to Howard Uniform - 10,000 hickory 2,000 redwood over 20 yrs

1957 / 1977 – Rev. John D. Longenecker - Made BPD Issue - Sold to Howard Uniform - 10,000 hickory 2,000 redwood over 20 yrs

1955 / 1979 – Carl Hagen - Made BPD Issue & his own Stick - Sold to Howard Uniform and Officers - 2.000 various wood types over 24 yrs

1974 / 1977 – Edward Bremer - Made his own Stick – Sold to Officers - 300 various wood types over 3 yrs

1977 / 2007 – P/O Joe Hlafka - Made his own Stick - Sold to Officers and Police Supply Shops - 10,000 various wood types over 30 yrs

![]()

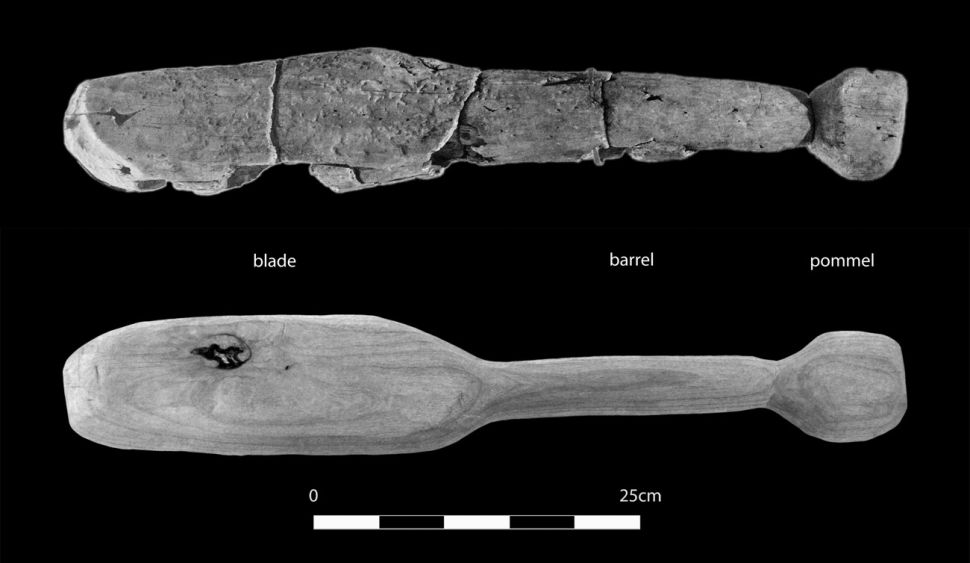

5,500-Year-Old Wooden Clubs Were Deadly Weapons

Oldest known Club

Oldest known Club

Carbon dated to 3530-3340 B.C.

Wood typically does not preserve well in the archaeological record, but the Thames beater was pulled out of the waterlogged soil on the north bank of the Thames River in the Chelsea area of London. It has been carbon dated to 3530-3340 B.C. and is now housed HERE in the Museum of London. Dyer described the club as a "Very badly made cricket bat," but much heavier at the tip.

Dyer enlisted a friend, a 30-year-old man in good health, to do the bashing, and told him to swing as hard as he could at the "skulls," as if he were in a battle for his life. The resulting fractures resembled injuries seen in the real Neolithic skulls. One fracture pattern closely matched a skull from the 5200 B.C. massacre site of Asparn Schletz in Austria, where archaeologists had previously speculated that wooden clubs might have been used as weapons. "We didn't go out aiming to replicate a particular injury, and when we got that fracture pattern, we were quite excited," Dyer said. "We knew right away that we had a match there."![]()

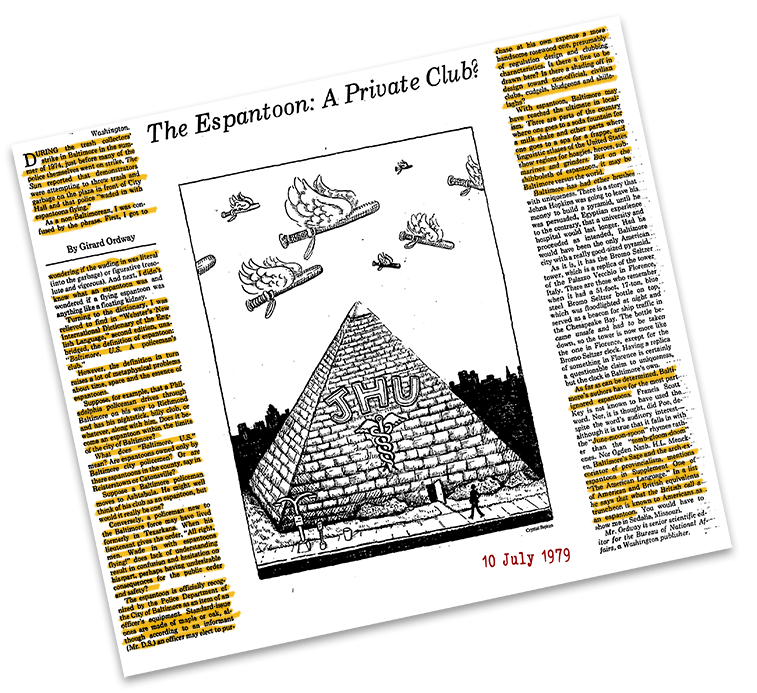

Above is the article that best helped us put our answer into words about what makes an espantoon an espantoon. To read the full article, click on the picture above, and it will take you to the article. You can click on it after it opens if you need to zoom in.

![]()

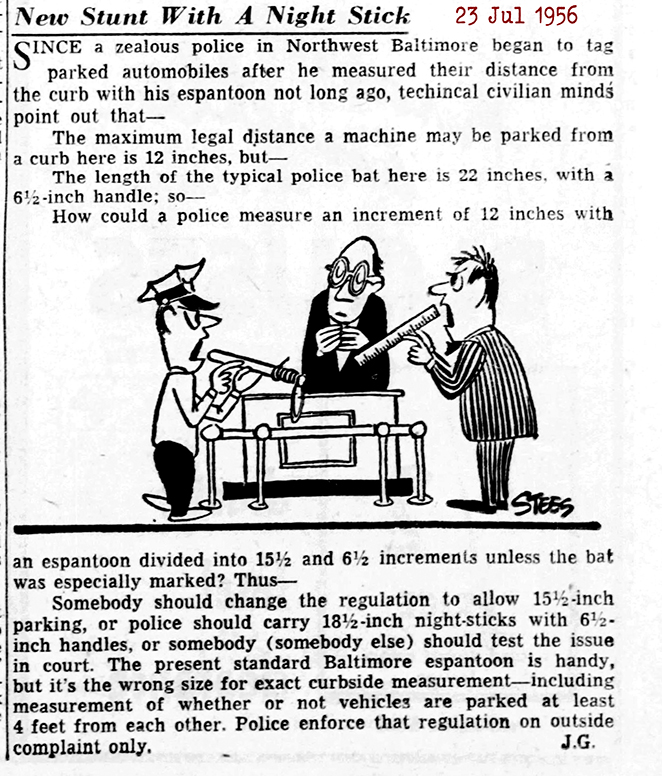

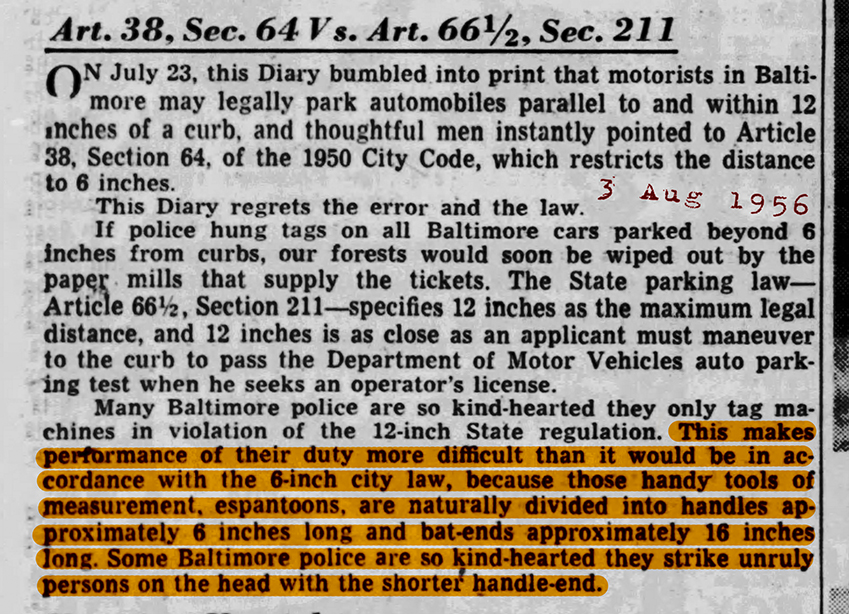

Do our sticks measure up?

![]()

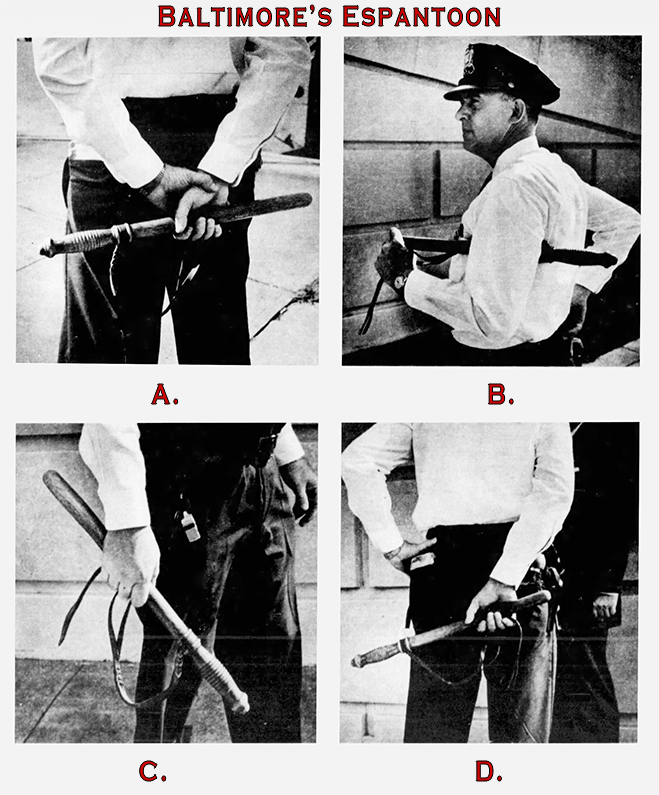

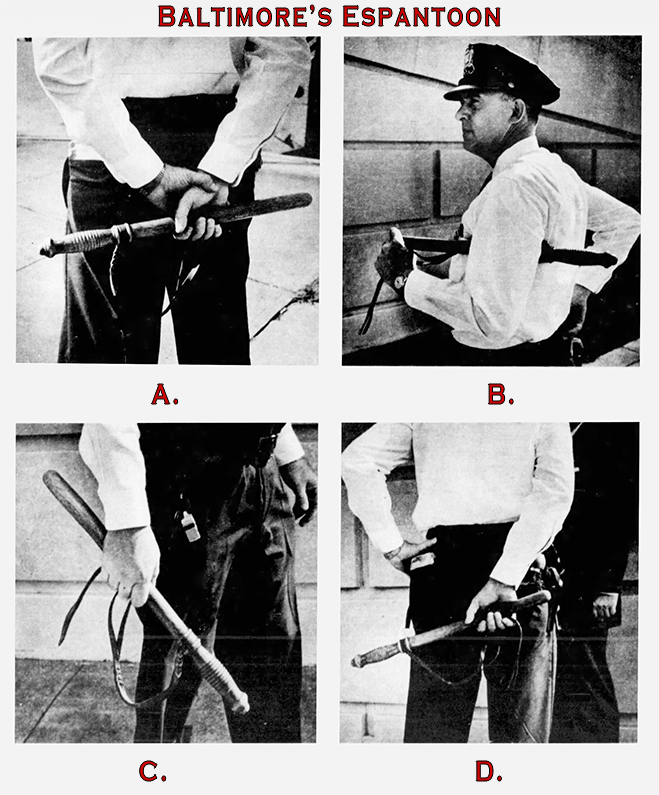

Baltimore Sun, August 3, 1956 As we know, our police are not striking with the "handle end"; they strike with the "barrel head" per their training, General Orders, or Policy #1111. As you look through the photos on this page, you'll see that, as far back as we could find, officers carried their sticks in a way that would have them holding the handle end of the shaft and swinging the "barrel head," often confused as the stick's "handle end," which demonstrates that this is how Baltimore police have always done this and what makes a nightstick an espantoon.

![]()

18 February 1937: Taxi Strike

Notice that in both places where we can see the espantoon, the officers are holding the Barrel Head out

Courtesy Robert Oros

Nice espantoon picture showing a nice Baltimore Police Espantoon.

Also notice it is held at the shaft with the Barrel Head / Striking end out ![]()

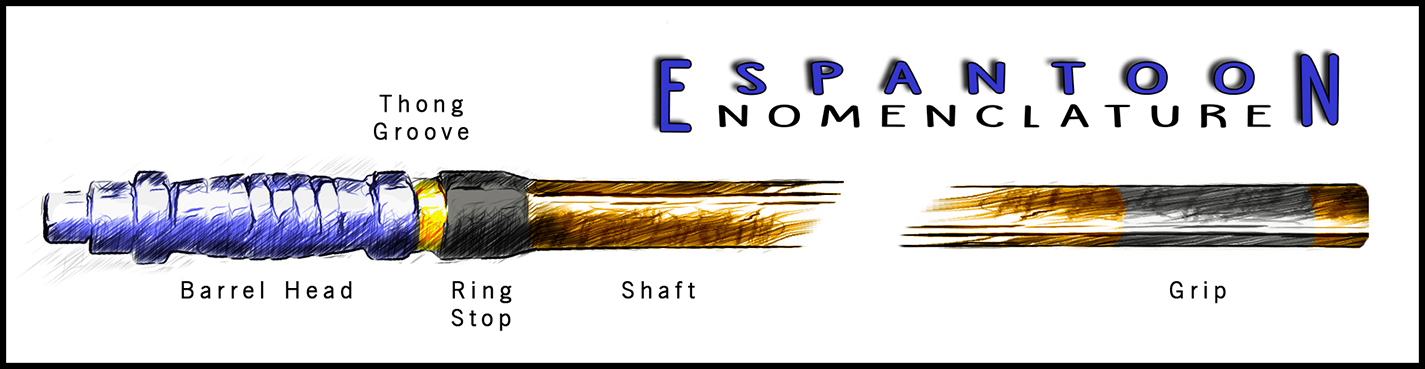

The blue portion of the espantoon in the above illustration is most often mistaken for the handle of the stick but is actually the striking end. It is called a barrelhead; this most likely comes as the result of an error in pronunciation, as in many blunt force weapons, the striking end is called a "burlhead." As in the Tomahawk and other such weapons, the blunt end can either be added or carved into the weapon. But here in Baltimore, with years of mispronunciation and a slight southern drawl, Burl sounds more like Barrel. So Burlhead became Barrelhead. A funny thing to add to this is that the shape of the Espantoon's burl head is also kind of shaped like a wine barrel, which added to the error. Now, in the same way, the JEEP a military vehicle that also has ties to Baltimore, has a name that was derived from the letters G.P. for General Purpose. G.P. said often enough and fast enough that it took on the sound of JEEP and long before it was manufactured and marketed as the JEEP it became JEEP and would have, with or without the JEEP's we know been forever called a Jeep; likewise, the Burl Head on the striking end of our espantoon will now and forever be called a Barrel Head

![]()

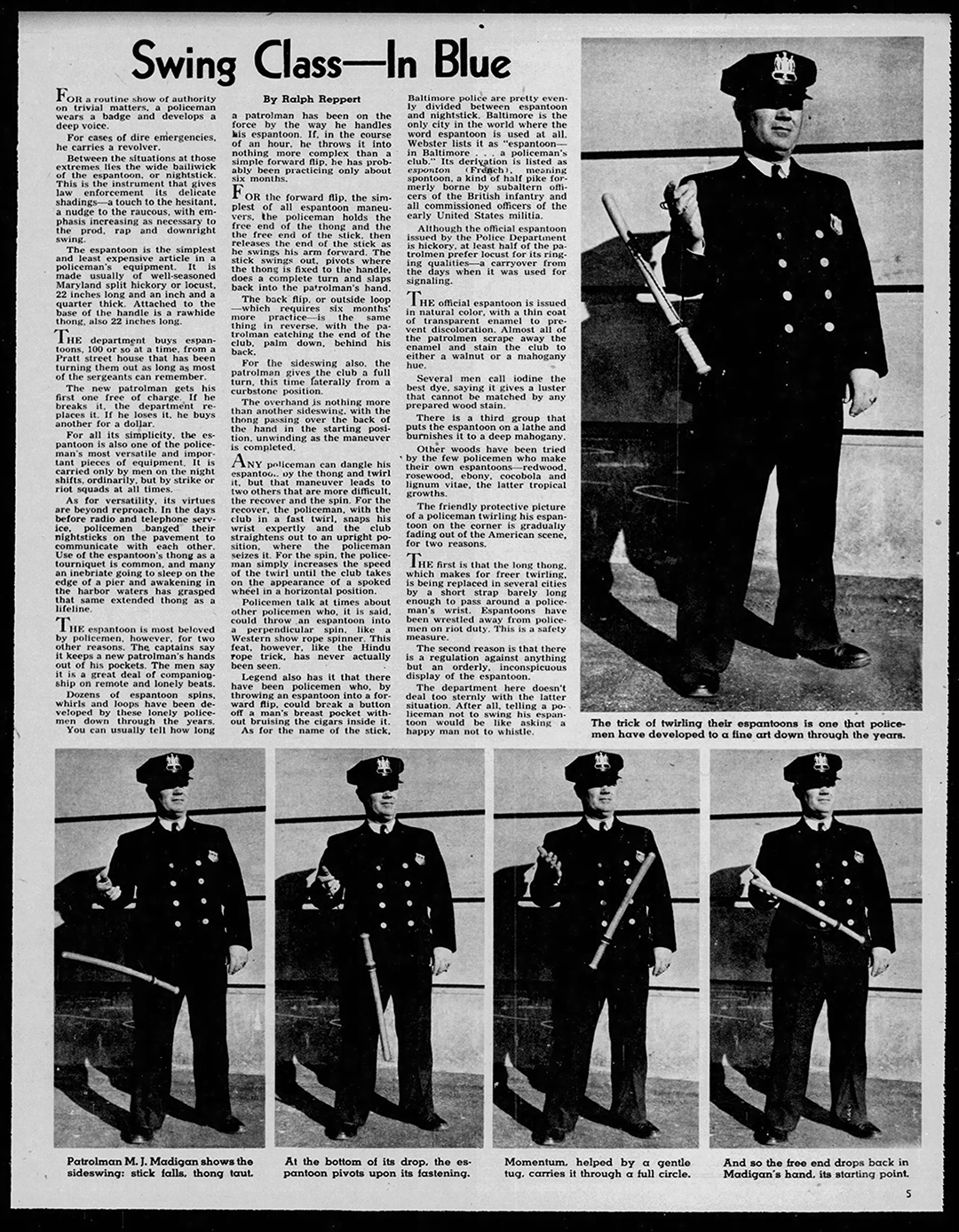

Teaching young officers how to spin the Espantoon

was Sgt Edwin Schillo

In the 1980s, those that went through the police academy were lucky to have an instructor named Sgt. Edwin Schillo. Sgt. Schillo took his own time during lunch breaks to teach any student that wanted to learn the art of spinning their Espantoon. I would bet for every stick Nightstick Joe Hlafka made during those days, Sgt. Schillo showed them not just how to use it to defend themselves but also how to spin it at the end of its leather strap, also known as the thong. So, we give special thanks to Sgt Edwin Schillo for the time he took to keep and the art of spinning the Espantoon to so many young police.

![]()

An illustration with a key shows the often mistaken handle, which is in fact the striking end.

What is an ESPANTOON

Nomenclature of the Espantoon

To be clear about the barrel-head and other parts of the espantoon, we took a Joseph "Nightstick Joe" Hlafka espantoon and painted the various parts using a color key and the nomenclature with a color key. Using BLUE for the barrelhead, or burlhead above, we can see how the barrelhead could be confused for a handle. We can also see how some old-timers might think it resembles a wine barrel and believe it could be why it was so named. When I was a young officer being told the parts, the old-timer actually said, "This is called the barrelhead; if you look, you can see it looks like an old wine barrel." If we look at the part painted YELLOW we see what is known as the "thong groove." This is where we weave a leather thong, and the groove serves to keep the leather strap or thong from slipping off the stick. Under the thong groove, we see a part we have painted GREY. This, aside from being part of the "thong groove," is known as the "ring stop" and is used to prevent the espantoon from sliding through the nightstick ring on an officer's belt. Under the "ring stop" is the "shaft. We left this stained the color of the stick until we reached the "grip. On some sticks, the grip can be turned into the stick, but most often it is just the part of the stick we feel most comfortable catching it at. It could be balanced differently for everyone. In the picture, we can see the thong or strap, which is used differently. For me, I like to loop it over my ring finger. I have seen some look it over their middle finger, others over their entire hand, kind of around all fingers. So we all have to try it different ways to see what is best for us.

Looking at the Pictures below, we can see that by paying attention to what we are doing, we can carry an espantoon in a way that keeps the barrel-head at our ready. Tucked under the weak arm with the grip end extending out toward the officer's back, it leaves the grip end ready for the officer to grab or grip with his or her strong hand in the event that it might be needed. In photo A) we see it is in the officer's strong hand. With the thong over a finger of the strong hand, if needed, he could turn his hand downward, allowing the stick to slide out under its own weight until it is stopped by the strap. Which would put the stick in his hand by the grip end with the striking end out and at the ready. Picture B) is as described above, tucked under the weak arm, ready to be grabbed with the strong hand at the grip end, which would leave the striking end again at the ready. Pictures C) and D) are similar in that the stick is held in the strong hand, with the thong over a finger, and the stick is held at the halfway point, or so, with the striking end pointing forward, allowing the officer to simply loosen their grip while the stick slides forward until the thong stops it from sliding, and the stick would be ready for use. The important thing about picture D) is that the stick is behind the officer's back, so while he is ready, he is not doing anything that could be seen as a threatening move. We can now see why these 4 pictures are a nice representation of how an officer can always be ready to protect himself or the public, but not walk around in a way that might be seen as threatening.

NOTE; We included a few non-Baltimore Police pics just to see how other agencies carry their batons, nightsticks, etc., and how when you carry them the way we carry ours, before long when you see others carrying them upside down and backward, it kind of jumps out to us as odd. This will provide a nice educational moment for those that might be interested, and maybe a little humor for those that don't get it or understand.

In the above picture, the letter "A" is marking off the portion of the stick known as the barrel-head. Notice how much cleaner the middle of the barrelhead is when compared to the shaft, especially the part of the shaft we have marked with the letter "B." The section we have marked with the letter "C" has a line at the top and a line at the bottom. This area, which we marked as area "C" has a lot of dirty hand marks, but it is not as dirty as the section we have marked with the letter "B." To us, this shows the officer handled it often down around that section marked "B," which could be an indication that this officer spun this stick as he walked his post. The constant catch and release of a stick while twirling it would put that portion of the stick in the hand most often. A stick with a light stain and no clear coat will absorb oil from the hands, then pick up and retain the most dirt. Especially when there is no swivel and the stick has to be caught and released more often to keep it going while preventing it from tangling up onto itself. Then, if we look at the stick between the portions marked "C," we can see the stick was carried most likely in the strong hand. Some guys learned to spin or twirl with their weak hand; most just use their strong hand. So this helps us not only date the stick but also prove how it was handled, and every hand print strengthens our feelings that this was a Baltimore-issued espantoon that was spun by a Baltimore officer, because other agencies do not allow an officer to carry an espantoon the way a Baltimore police officer would.

Taking a look at the photo before this, the one where the officer is seen in four variations, we'll see his hand is most often held in the center of the shaft. Now we have to add to the holding of the stick at the shaft what happens when the stick is actually used, either to strike someone, to jab someone, or to pry their arm, perhaps behind their back or from being wrapped around someone's neck or body. It also works to put someone in an arm bar and then to either walk them to the wagon or to cuff them when they are resisting an officer's attempts to subdue them. As long as it is resisting with an intent to flee rather than resisting while assaulting the officer, that determines how an officer reacts. This means an officer's actions are often reactions driven by the subject being arrested.

We'll take a look at these pictures and others to see better what is meant by "carried at the shaft." If we look at the four picture group, in particular the second picture, the one marked with the letter "B," we'll see how the stick was most often tucked up under the officer's weak arm. Unlike the picture most guys saw, including myself, once the stick was tucked under the weak arm, the strong hand reached up and across to hold the stick at that section earlier marked with the letter "C," in the "A, B, C' picture. My favorite picture is below, showing an officer getting back into his car. In it, we see his hand at the grip end of the shaft and the barrel-head extended forward.

Courtesy Eli Alaman

22 February 1941: Strike, Baltimore Police

Looking at the back of the officer closest to us, we can see where his Espantoon comes from under his arm, confirming that even in the 1930s the "barrelhead," end was striking out. Showing that as far back as the 30's the officer held the stick by the shaft, striking with the barrelhead.

Courtesy Eli Alaman

22 February 1941: Strike, Baltimore Police

If we look closely at the officer furthest to the right, we can see he has his stick with the barrelhead out; this is how Ken carried it when he was at rest. This allowed him to simply tilt his hand forward, allowing the stick to slide down until it was where he wanted it in his hand, then grip it so it would be ready in the event someone was closing in on him or his partners. Most often, the thong or strap would be looped over his ring finger, so when it reached the end of the strap, it would stop, and he would tighten his grip to hold it in the perfect position for him. With his head forward, if he needed to, he could have quickly used it to jab a suspect that was closing in on him. Jabbing was less violent than striking. However, the suspect's actions as he closed in on an officer determined whether the officer would strike or jab. They used to teach, "Reasonable and Prudent," what a reasonable and prudent person would do, and if a person decided they could attack an officer, then of course the officer had every right to defend himself.

Courtesy Eli Alaman

Courtesy Eli Alaman

22 February 1941: Strike, Baltimore Police

Courtesy Eli Alaman

Courtesy Eli Alaman

22 February 1941: Strike, Baltimore Police

Take a look at the officer in the bubble from a 1941 photograph where he is spinning his espantoon on the end of the thong or strap. It is a very nice picture, and given the year of the picture, it is nice to see it being done so long ago. Also, 1941 would have been long before a swivel was added to the strap or thong. This picture was taken by Eli Alaman

Courtesy Eli Alaman

22 February 1941: Strike, Baltimore Police

Taking a look at the motor's officer walking toward the right side of the picture, he is holding the stick at the bottom of the shaft, with the barrel head out front and away from his hand. Looking close, you can see that he is one of the guys that carved the barrel head so it was no longer convex. A lot of guys would reshape their espantoon to make it unique to them.

Courtesy Robert Oros

Nice espantoon picture showing a nice Baltimore Police-issued espantoon.

Looking more closely, we can also see he had a swivel added to the thong.

![]()

Just as the Espantoon wasn't only used for self-defense,

The Rattle wasn't only used for communication

Both The Espantoon and Rattle were used as Impact Weapons

and/or for communicating with other officers in the area.

For more, Click HERE or on the picture above

![]()

This is the most commonly used "striking position." It is also a catch or release position for holding the stick when spinning or twisting the espantoon. Notice in this picture that the officer is carrying his espantoon with the barrel head out. This practice has been the way Baltimore police have carried their sticks, going back to the late 1700's and early 1800s. It is what makes a nightstick an espantoon. The espantoon, also known as a nightstick, is a traditional symbol of authority for Baltimore police officers. Its unique design, with the barrel (or burl) head carried outward, is for self-defense and crowd control. Its uniqueness is believed to have originated here in the late 18th century and has been consistently followed ever since. With the barrel head facing outward, it allows for quick and effective strikes, or jabs, while maintaining a non-threatening appearance. This longstanding practice showcases the rich history and traditions of the Baltimore police force. The distinctive carrying style has become an iconic feature of Baltimore's law enforcement history and also serves as a visual representation of their role in maintaining law and order while reflecting the city's deep-rooted connection to its policing heritage.![]()

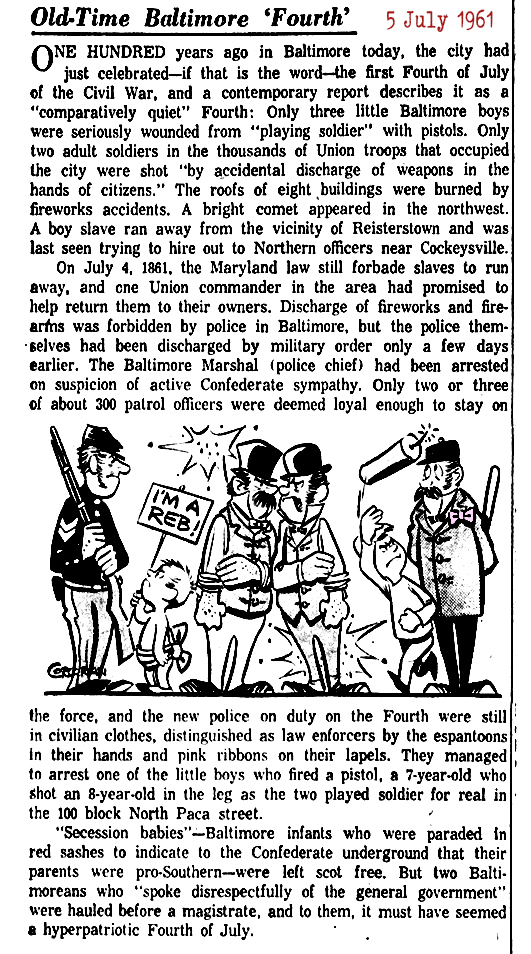

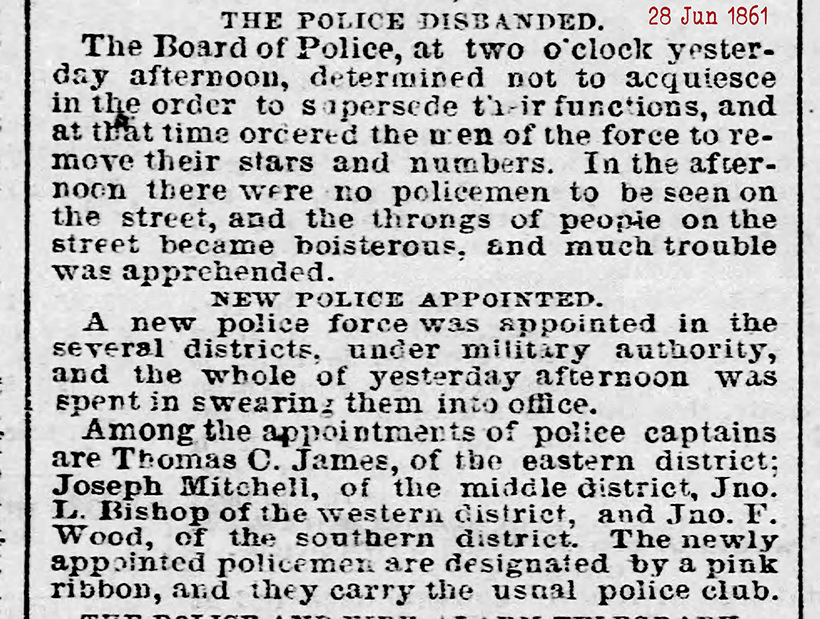

1861 Baltimore Police dressed in plain clothes and were distinguished by

a pink ribbon on their left lapel, and an espantoon in their hands

CLICK HERE OR ON PIC ABOVE FOR FULL SIZE ARTICLE

This clipping was taken from a 28 June 1861, Sun paper. Notice it says

"A new police force was appointed in several districts under military authority."

"Newly appointed policemen were designated by a Pink Ribbon, and

they carried the usual Police Club," which in Baltimore is the Espantoon

TO SEE FULL PAGE CLICK HERE OR ON THE ABOVE ARTICLE

![]()

Reverend McKenney and Reverend Longenecker

This is one of the old Baltimore Police Department-issued Espantoons made between 1937 and 1977 by either Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney or Rev. John D. Longenecker. An interesting meeting occurred after years of the elder reverend [McKenney] turning police sticks for Howard Uniform to be distributed to the men and women of the Baltimore Police Department. The reverend [McKenney] was set to retire, and as such, he listed his tools for sale in a local newspaper. By the time the second reverend [Longenecker] saw the listing, the tools—a wood lathe and some other woodworking tools—were gone. Reverend McKenney had decided to, and by then he had already given his tools to a local boy’s school. However, he told the second reverend, who, after a brief handshake, he knew was a woodworker, that if he was interested and could gather the necessary tools himself, he would help him get the contract to turn Espantoons for Howard Uniform Espantoon. Not long after that meeting, the two reverends were together, with the senior reverend teaching the junior some of his tricks for turning the Baltimore Espantoon. There may be something to the number of grooves turned into the barrel head of the Baltimore espantoon, but we’ll cover that in another section. The younger reverend had been turning chair parts on a lathe since he was a small boy working at his family's furniture-making business in PA (it was his job to turn the rails for the chairs his father and older brothers were making). So, he picked up on Reverend McKenney’s pattern real fast, and best of all, he had a photographic memory, so he was able to turn them without a template. Well, I am told by a family member that he didn't use a template or pattern, but he did have one stick, the stick he got from Reverend McKenney hanging on a wall not far from his lathe, and all of the Longenecker Espantoons were identical and pretty close to the same as the McKenney Espantoon. If I remember correctly, the second Reverend said it took him 1 hour to do a stick at first, but by the time he was ready to start production, he was able to turn them at a much faster rate of 3 to 4 of them in that same hour.

![]()

Click HERE or the above Article

Click HERE or the above Article

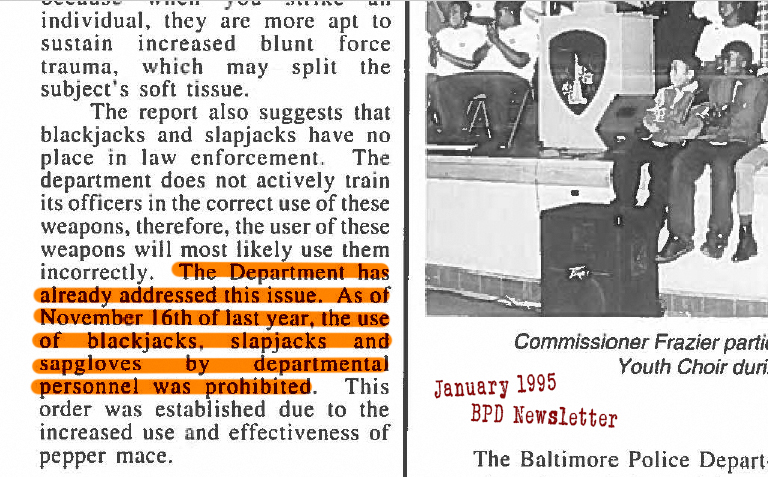

Here is who suggested doing away with the slapjack, but it was on

16 November 1994, that the department ended the authorized use of the Slapjack

Click HERE or on the picture above for a full newsletter.

Baltimore Police Newsletter

January 1995

![]()

We have and will continue to see this picture on the site; look where the stick is most often held, and we'll see why the handprints are where they are and how this is a Baltimore thing. Obviously, this doesn't just go for this stick; go get your stick, or the next time you pick up a stick at a flea market or antique store, pick it up and look for these telltale signs of where the officer's hands most often carried it. After all, no other agency not only had their officers turn a nightstick around and use the handle as the business end, but if we read our general orders, we see several lines describing the various batons allowed in use by the department. When they describe the espantoon, it is described as follows: espantoon—a wooden baton between 22-25 inches in length, with the striking end of the baton being between 1 1/2 - 1 3/4 inches in diameter and the grip end being 1-3/8 inches in diameter. This baton has color restrictions and shall only be coated in an oak, ash, maple, hickory, or rosewood finish. Decorations are prohibited.

If we look close we can see where the hand most often held this stick

It is cleaner at the end of the shaft furthest away from the barrel head

NOTE: We are not saying we won't find marks where officers from other agencies didn't carry their batons at the shaft; what we are saying is that in most cases where the stick is not a straight stick and does have a handle, the handle will not be as clean as the end opposite our Espantoon's barrel-head.

To better understand what makes an Espantoon an Espantoon, we have to take into consideration what is the different between, a nightstick carried in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, or by any other police officer in any other police department anywhere in this country. Basically, other than Chicago that had a unique turning pattern to their baton’s handle, that could help identify it as a Chicago stick. Baltimore may not have a pattern for optional officer self purchased sticks, the issued sticks were the same design from 1937 to 1992. Before 1937, the sticks were not much different, the craftsmanship was slightly better looking. Put either the older versions or the more modern version on a table with other batons from around the world, and a Baltimore baton could easily be picked from the crowd of sticks.

![]()

Below are Some Baltimore Police Issued Espantoons

Carl Hagen

Turned espantoons from 1955 to 1979![]()

1920's Baltimore Police Issue

Issued Stick 1937 - 1977

Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney & Rev. John D. Longenecker

Issued Stick 1937 - 1977

Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney & Rev. John D. Longenecker

Issued Stick 1937 - 1977

Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney & Rev. John D. Longenecker

Issued Stick 1937 - 1977

Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney & Rev. John D. Longenecker

Issued Stick 1937 - 1977

Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney & Rev. John D. Longenecker ![]()

Click HERE to see full size article ![]()

Courtesy David Eastman

Look at the officer's espantoon seen on the right side of this pic, and notice how it is carried, held in his right hand with the thong ran through his fingers, and the barrel head out as he is gripping it by the shaft of the espantoon. This pic is taken in the early 1900's but we can clearly see he carries it the way it is carried today, indicating the striking end back then, was as it was in the 1960's and 1970's when Ken's uncles walked a beat in Baltimore, and the 1980/90's when Ken walked a beat in Baltimore. The striking end in Baltimore would be considered the handle to all other jurisdictions, and if other departments used it the way Baltimore did, it was only Baltimore that had it in the officer's general orders that the striking end was the wider end of the baton, the handle in Baltimore is the thinner end, the end known here as the "Shaft."![]()

Issued Stick 1937 - 1977

Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney & Rev. John D. Longenecker - This has one edge shaved flat so it would stay in place without popping out every time we turn a sharp corner or hit a pothole. The flat spot helps keep it in place when it's forced between the dashboard padding and the transmission hump.

Issued Stick 1937 - 1977

Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney & Rev. John D. Longenecker - There was a time in the mid 50's that officers would shave the Barrel Head of their Espantoon taking it from convex to flat/straight then add or re-cut grooves in the new Barrelhead

Issued Stick 1937 - 1977

Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney & Rev. John D. Longenecker

This is another case of someone attempting to straighten the convex, "Barrel-Head"

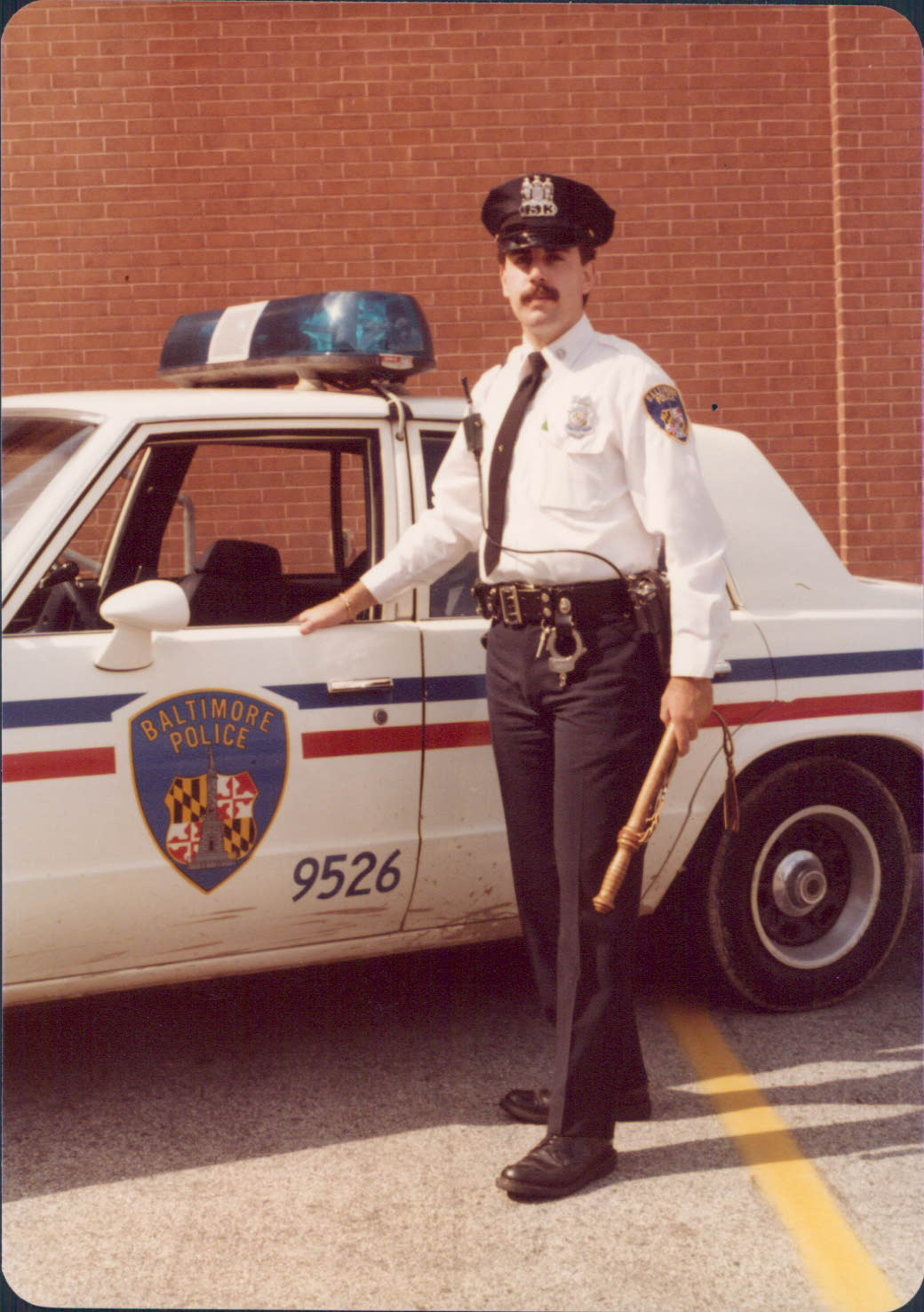

Issued Stick 1987

This was issued to me on 17 June 1987 when I was hired and sworn in

Issued Stick 1937 - 1977

Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney & Rev. John D. Longenecker

Issued Stick 1937 - 1977

Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney & Rev. John D. Longenecker

Jim Brock - Perfection Collection

Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney & Rev. John D. Longenecker Model - Circa 2015

Non-Issue Stick 1937 - 1977

Non-Issue Stick 1937 - 1977

Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney & Rev. John D. Longenecker

Carl Hagen turned sold through Howard Uniform circa 1965

Carl Hagen

This is an early Carl Hagen Stick, it came while he was still turning them to the size of an issue stick, and isn't too far off of the standard issue stick, he just added a few things to make it stand out from the issue stick, the barrel-head is a little over sized and it is turned from an oak.

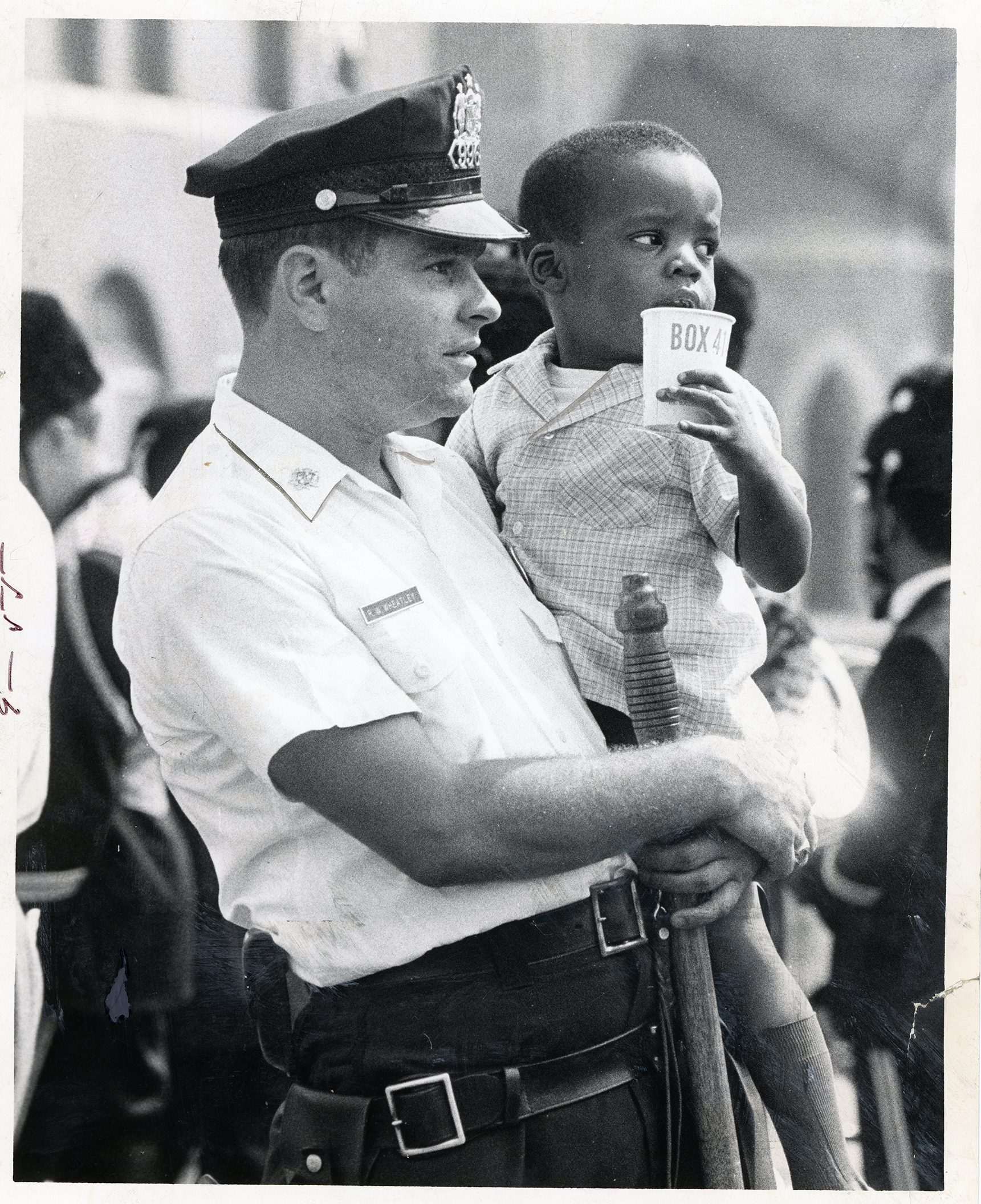

P/O Raymond Wheatley holding a Carl Hagen stick, notice how Carl rounded the tops of his sticks, this is a nice old stick. Also, notice how Officer Wheatley picked up a small child to help him better see a parade that he had attended, but couldn't enjoy over the crowd. Officer Wheatley not only gave the kid a lift, bought him a cup of soda too.

Carl Hagen 1955 - 1979

This is one of Carl's first unique designs, it was done solely by him and became a popular design from his sticks. In the next pic, we'll see Officer Ray Wheatley holding a Carl Hagen Espantoon, it is more of an issue cut, but with a modern (at the time) cut, the cut that ended up being refined into the sticks we saw turned by Ed Bremer and Joe Hlafka.

Jim Brock - Perfection Collection - Carl Hagen Model - Circa 2015

Jim Brock - Perfection Collection Thin Blue Line Stick - Carl Hagen Model - Circa 2015

Prior to Issued Sticks 1954 - 1960

Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney & Carl Hagen - At some point when McKenney had retired from turning sticks, he had donated his lathe and tools to a boy's school out west, and before meeting Reverend Longenecker, McKenney he had met Carl Hagen and showed him how to turn sticks, for whatever reason, Carl turned some sticks for Howard Uniform, he just didn't get the 500+ stick a year contracts from Howard Uniform that the Reverends McKenney & Longenecker received.

Carl Hagen - 1955 - 1979

Jim Brock - Perfection Collection Lignum vitae #001 Stick

Lignum vitae is on top 10 lists of hardest woods depending on the list it is either 2nd or 4th One might be how dense the wood is, while the other might be how dense the guy/gal is that is trying to spelling Lignum Vitae Joe Hlafka Model Circa 2015

Ed Bremer - 1974 - 1977

Jim Brock - Edward Bremer Model - Circa 2015

1977 - 2007 - P/O Joe Hlafka

Joe Hlafka

1987 - I bought this from Joe Hlafka direct, apparently someone ordered it, paid half down and before it was done they found their stick and told Joe, they didn't need it anymore, could he sell it to someone for the remainder of the balance, I was the lucky guy that talked to Joe about a stick, and he gave me the stick for $12.00. I have replaced the thong twice, had it, "I say" stolen once, the guy that took it, called it, "found". How you can find an espantoon in the trunk of a patrol car, and not think it must belong to someone. Not to mention DRISCOLL is written around the stick in blue sharpie by the Ring Stop - Anyway, it is a 30 plus-year-old stick. BTW I stopped the kid as he was going out to his post, so I loan it to him for the shift, and told him to get it back to me, "in my hand," the next day. I couldn't send him on the streets without a stick.

I Turned this Myself

1990 - I put the extra groove on the shaft because after carrying it for a day or two I realized the stick felt good, weight was nice, but the shaft was too think to hold on while swinging it, So I taped the thong to the barrel-head with Duct tape, and put the stick back on the lathe and shaved a hand-grip in the shaft. After shaving the shaft to a comfortable grip, I was done, pulled the tape, and it was a spinner, or umm, I mean a winner,

Irish Shillelagh

This is to point out the striking part of this weapon, that blunt looking rock, or fist shaped portion at the end of this weapon, and any blunt force weapon is called the "Burl-Head". On the Espantoon the blunt striking end resembles, and is often mistaken for the weapon's handle is called the "Barrel-Head." Most likely stemming from a misunderstanding caused by Baltimore's southern drawl, or bad "accent," causing a listener to misunderstand what a speaker may have said, Burl-head to thinking the speaker said, "Barrel-head." In 1987 when an old timer told me, he even pointed to the shape and, said, this is because this looks like an old wine barrel. Truth be told, it wasn't a barrel at all, it's a burl.

Barrel Head

This is the Barrel-head of one of Carl Hagen's early sticks - This Rounded off top end was exclusive to Carl Hagen, and was found more on the West side of Baltimore than the East. The East-side Espantoons saw more of a two or three tiered layers each with a hard edge that sat atop the espantoon like a crown on top the barrel head end of the stick. If we look at Carl's earlier stuff, he had a two or three-tiered top edge also, but it wasn't a hard edge. Carl had a super soft, smooth transition going tier to tier on the barrel head.

Barrel Head

This is the Barrel-head from one of Ed Bremer's early sticks, he put what he called a "Nib" on the top of all his Barrel head. Mr. Bremer felt he saved lives, both of Officers and Suspects because as he once said, "Nightsticks Save Lives, Preventing Officers from a need to escalate from hand-to-hand combat to the use of a firearm." The faster we can get a suspect into cuffs the safer it is for both the officer and the suspect. This stick is turned from Lignum vitae, a wood that was banned by the department as it was too heavy, hard and they felt could cause serious injury or death.

The “Barrel Head” of Baltimore's Issued Espantoon

Interesting Theory, in 2008 while researching Baltimore’s Espantoon, we were looking for the normal questions, like, why we called it an, Espantoon? Where did the word, Espantoon, come from? When did it start etc.? Etc. etc. etc…. Along the way other observations were made, like when we see a Chicago Nightstick, we know it is from Chicago on sight. The shape of the handle is cut in such a way that often even in the shadows of a picture, you can make out their handle cut, it is that unique.

This is a Chicago Stick

Notice the rings are on the top and bottom of the handle but skip the center

This pattern carries back as far as we can find in their nightsticks

Baltimore didn’t have such a design, if we go back far enough, we’ll see at one time we had as many as twenty, “ring grooves” on the barrel head, then later sometime during the time period that Reverend W. Gibbs McKenney was turning our sticks there was a change, at first it looked like he may had just made a simpler design, but it made me and some others that were helping with my research stop and wonder, were the near twenty ring grooves the same as the twenty points on the twenty point badge? Did each ring represent a ward in the city? When the good Reverend came along and made his design, did he reduce it to seven to represent the seven districts that protected the city at that time. We will never know, but it does give us something to think about.

Not long ago while watching re-runs of Ink Masters, I saw an episode in which they were drawing, and then tattooing the Statue of Liberty. One of the artists made what was said to have been a crucial error, he only drew six of the seven rays/spikes on the Statue of Liberty's crown. The other artists made a big deal, such a big deal that it seemed it was less than about detail, and more about symbology. So, I looked it up and found that according to the website of the National Park Service, the seven spikes on the Statue of Liberty's crown represent the seven seas, and the seven continents of the world.

This is one of Reverend McKenney's Espantoons Notice

the Barrel Head has Seven grooves. This pattern carries from the late 30's when

Rev McKenney turned them through 1977 while Rev Longenecker turned them

and on until 1996 when they were no longer issued by the department

Could these seven grooves, in the design of our stick by Reverend McKenney have a similar meaning? In 1937, would he have given the seven spikes of the Statue of Liberty's crown any thought at all? I doubt it, so I asked myself again, if it is not due to the seven districts of police that served and protected the city of Baltimore at that time. Then we have to take into consideration Reverend McKenney, and his profession then ask ourselves, “could there be a religious link to the number seven?” To answer this, I looked up religious links to the number seven, where I found; the number seven has had significance in almost every major religion. In the Old Testament, the world was created in six days and God rested on the seventh, creating the basis of the seven-day-week we still use to this day. In the New Testament the number seven symbolizes the unity of the four corners of the earth with the Holy Trinity. The number seven is also featured in the Book of Revelation (seven churches, seven angels, seven seals, seven trumpets, and seven stars). The Koran speaks of seven heavens, and Muslim pilgrims walk around the Kaaba in Mecca (Islam’s most sacred site) seven times. In Hinduism there are seven higher worlds, and seven underworlds, and in Buddhism the newborn Buddha rises and takes seven steps. So, whatever gives us the most comfort, it could just be an easy design that helps the maker kick them out at a rate of four per hour, it could be one groove for each of the seven districts (ED, CD, NWD, ND, NED, SWD, SD) that served the city at the time. We didn’t have a SED until 1958/59 and WD was non-operational for a time being. So, it could have been that. But most likely given that for forty years from 1937 until 1977 our sticks were turned by two Reverends. First from 1937 until 1957 Rev W. Gibbs McKenney, made our BPD Issue Espantoons, then in 1957 when he retired from the business he donated his machines to a local boy’s school, shortly after he met and Rev. John D. Longenecker learning he was a woodworker, he agreed to train him and help get him the contract he was walking away from. From 1957 until 1977 Rev. John D. Longenecker turned our sticks using the design given to him from Rev McKenney. Over the course of 40 years between the two reverends a combined 20,000 hickory, and 4,000 Redwood Espantoons were turned. Their sticks were sold to Baltimore City Police, as well as several other jurisdictions and security companies. More can be read elsewhere on this page about both Rev. W. Gibbs McKenney, and Rev. John D. Longenecker how they met and what they did.

Here we hope to just give us all a little something to think about as to why the design may have become what it did.

I purchased this stick from Joe personally and carried during my time in Patrol

If we count the grooves we see he also turned seven grooves, which was

kind of an unwritten custom of our department's Espantoons.

As an interesting side note, many of the guys that followed alongside Reverend Longenecker, like Carl Hagen who turned from 1955 to 1979, Edward Bremer turned out Espantoons from 1974 until 1977, and our own, Officer Joseph "Nightstick Joe" Hlafka who from 1977 until 2007 more often than not, turned seven grooves into the barrel heads of their sticks. There is nothing in writing to tell us why they did this, if it was for the reason the Statue of Liberty has seven spikes, because of the religious ties to the number seven, perhaps the reverends felt it would offer a kind of protection, or maybe it was just quicker and easier to turn seven simple grooves. We can pick whatever makes us feel better about the design, because until we can talk to a family member to see what they were told, we may never know. the good thing, I am friends with Joe's wife, and I was first contacted by Reverend Longenecker's stepson. So, we have a contact, and can look for family members of the others we know turned our Espantoons.

Grip Designs

Grip Designs

BALTIMORE POLICE DEPARTMENT TRAINING BULLETIN

Guidelines EDWARD T. NORRIS POLICE COMMISSIONER

December 12, 1987

Revised / Reviewed: August 2002 Vol. 12, No. 10

ESPANTOON HISTORY The espantoon according to Webster’s Dictionary is: “in Baltimore; a policeman’s nightstick.” The term is a derivative of the word “Spontoon” that dates back to the weapon and symbol of authority the Officers of the Roman Legions carried.. In 1784 Baltimore appointed paid police officers. From that time until the middle 1960's when the department switched to motorized patrol units the sight of the officer “walking the beat” was a commonplace reassurance. One of the most unique elements of a foot patrol officer in any large East Coast American City was their ability to twirl the “nightstick” until it literally danced. Obviously then, as now, the espantoon is a defensive weapon. The purpose of twirling the espantoon was multifold. The days before the portable two-way radio, the officer was alone and the “twirling” created and protected a “personal zone.” Another benefit of twirling the espantoon was that a familiarity was gained with the “stick” that developed confidence carrying the espantoon. The espantoon was also used for communications. A rapid tapping of the espantoon signaled a warning to others or a call for help. A flip of the espantoon, falling free of the hand striking the concrete, created a unique “ring.” Even today foot patrol officers use this technique to signal each other. It is extremely effective on quiet nights. Even when “tapped” in a large crowd, usually another officer is the only one to notice. Training Guideline Vol. 12, No. 10 Page - 2 - Departmental regulations allow an officer to substitute a personally purchased espantoon for the one issued by the department, provided the substitute is similar in size, composition and design to the issued equipment. The departmental issued espantoon is 22" long by 1 1/4" in diameter and is solid wood. There is a handle on one end with a groove to attach a leather strap or thong. The thong extends from the groove to the bottom of the espantoon.

COME-ALONG AND HANDCUFFING ASSIST TECHNIQUE There are a variety of uses for the espantoon as a come-along or to assist in the handcuffing of an arrestee. Most are too complicated to describe briefly here. A key element to all of these techniques is for the officer to retain control of the espantoon at all times. The espantoon is primarily used as a lever to add power (torque) to the officers hand and arm movement. The speed of the top of the espantoon is essential. Bring the espantoon (with one hand) in a cocked position and strike forward in a slashing move. Make sure the wrist is snapped forward to accelerate the top two inches of the espantoon for maximum power. Do not snap back after impact. Follow through across your body. If a second immediate strike is required, deliver it in a back hand method, again snapping the wrist for maximum power.

JABBING AREAS AND TECHNIQUE To jab an assailant with the espantoon is an alternative method of stopping an assault to gain control. Jabbing is especially effective in close quarter confrontations such as a small hallway or in a large crowd. This would include any situation where “swinging” the espantoon would not be effective and/or would endanger others. The most effective target area for using a jab is the stomach area. A jab with the espantoon when carried in a single hand short reach position, is very effective against a sudden assault. A jab in the single hand long reach position has limited applications, such as keeping a subject or assailant at bay. The most effective jabbing technique is utilizing both hands. One hand close to the top of the espantoon while having the other hand at the bottom; gun away from the assailant. The technique is identical to using a bayonet on a rifle. Step forward to the assailant thrusting the end of the espantoon in the stomach area while lifting upwards. Both maneuvers are done with power. Training Guideline Vol. 12, No. 7 Page - 3 - Historically, most officers have made or purchased their own espantoons. While all are required to be made entirely of wood and similar to the size of the issued model, each one is unique. The variations of wood tones, size and shapes make them very personal. Often the same espantoon is carried for an entire career regardless of rank attained or duty assignments. The espantoon has sometimes become a family heirloom and passed on to younger generations of officers. The term “nightstick” was derived from the fact that officers were required to carry the espantoon during the “night-time” hours i.e.:4 x 12 and 12 x 8 shifts. It was optional during daylight hours. Police Officers are encouraged to have their espantoons with them whenever on duty. In the escalation of force, the use of espantoon is a step below the service revolver. The espantoon gives the officer the option and a greater degree of safety in the use of force. If the assailant is overpowering the officer’s attempt to defend himself, the espantoon can be utilized effectively to gain control. If the espantoon is left in the car or has otherwise been disregarded, the options for self-defense are severely limited..

DEFENSIVE USE The proper method for carrying the espantoon is in a “short reach” position in the weak (non gun) hand with the index or middle finger through the leather thong. When interviewing one or more potentially hostile suspects, the espantoon may be placed under one arm. This enables the officer to utilize both hands to write information.

STRIKING AREAS AND TECHNIQUES Often the question is asked, “Do I strike with my strong hand?” Most officers will use their strong hand because it is a natural tendency in high stress situations, but your weak hand is also acceptable. If you spin or twirl your espantoon, use the hand that will be utilized for striking. The twirling of the espantoon will enable you to learn its exact length. This knowledge will increase familiarity and confidence as an extension of your arm. Care and consideration should be given when and where you should “twirl the stick.” The espantoon should not be spun in close areas to avoid the possibility of injury to others or property damage. In some situations the espantoon may appear better left in the ring. If the espantoon is too heavy or feels uncomfortable, the officer should obtain a lighter espantoon. The power of the espantoon is developed by the speed not the mass. An espantoon that is too heavy for the officer will be ineffective. Whenever an officer is forced to strike a person, he must only hit as hard as necessary to stop an assailant in an effort to gain control to effect an arrest.

Training Guideline Vol. 12, No. 7 Page - 4 - The best target areas are the legs. The point of impact should be on the outside rear quadrant of the upper leg about four inches above the knee. That is where the common peroneal nerve branches off from the sciatic nerve. Striking this area will cause an involuntary bending reflex action of the leg. In a sympathetic nerve reaction the other leg will also “buckle” causing the assailant to fall to the ground. On top of the calf has the same stunning effect. Do not strike for the knee joint which can cause permanent damage to bones, tendons and muscles. While the legs are the best target areas, an officer is not limited to the legs. Any strike to the head must be avoided. Courts have held that a strike to the head with an impact weapon is tantamount to using deadly force. To strike with the espantoon an officer should hold same in the “long reach” position. The hand should be at the base with the index finger through the leather thong. The striking point should be the top two inches of the upper section. These methods leave the hands free and gives immediate access to the espantoon. These techniques are not offensive but helps the officer to control a situation better and with more confidence. If the officer is in a situation where the escalation of force seems imminent; drawing the espantoon from the ring tends to be offensive and aggravates the situation. When attempting to control a person or a situation, neither “slapping” the free end of the “stick” into an open hand nor pointing the espantoon in a threatening manner is advisable. These actions provoke people and place the officer in greater peril.

![]()

The Perfection Collection

The Perfection Collection was a well-turned set of sticks turned to replicate

four of Baltimore's best-known nightstick espantoon turners

Department Issued turned by one of two Reverends

Then Three well known highly collectable stick makers

Carl Hagen, Ed Bremmer and, Joe Hlafka

Top Down - Department Issued Turned by Rev McKenney or Rev. Longenecker

Carl Hagen, Edward Bremmer, and Joseph "Nightstick Joe" Hlafka

Webster’s Third Edition: “An Espantoon In Baltimore, a policeman’s stick”

We should Start out by saying we collect Nightsticks, Espantoons, Batons Etc.

If you have one for sale, or donation let us know.

We particularly like Baltimore Sticks, but collect them all. We hope to start a Baltimore Police Museum and would like to have as many we can to show what police have used for years to protect themselves and the public. It will be a rolling museum at first, and they will be used to show the differences over the years, as well to show how they wear, do to their having been carried everywhere with an officer over his or her carreer.

In Other Cities It’s Just A Policeman’s Club

by Reynold Stantley

Once upon a midnight hot

While I pondered “on the spot”

Over books with knowledge crammed

Feeling like a person damned

While I peered all board in June

seeking the meaning of Espantoon

Came a Raven black and geaven

In his eyes dull gloom and engraven

Then he opened wide his beak

Gave a most unearthly squeak

Quotas the Raven “take a hop;

“Espantoon? Go ask a cop”

The story of a lost investigator

You see it all happen this way: the man who sits in the editorial sanctum and likes speed and brevity along with accuracy and honesty handed me a newspaper clipping. – He told me to read it. I did. It related the sad land tale of a British Marine from the H. M. S. Exeter who had an altercation with two policemen at Eutaw and Franklin Streets. He lost, of course!

One thing struck me right between the eyes. It was the report of one of the policemen, a sergeant, that stated; “I struck him across his face with my Espantoon.”

So That’s What it’s All About!

Straightaway I asked the host – “What’s an Espantoon?”

He replied;

“That’s what I want you to dig up. It’s a policeman’s club, and the term is particular to Baltimore. What I want you to do is to find out the derivation of Espantoon, and while you’re at it you might trace the Swagger Stick. It was carried by the British sailor, you know.” (Turns out the sailor struck the Officer and Sergeant with that Swagger Stick)

I saluted, did an about-face and left his office gaily. Believing I had a cinch job.

All I have to say now is that if you ever want to play a cruel joke on some family or friendly enemy, get them to look up Espantoon. If he is of a sensitive nature he will probably become a raving maniac.

O.K. next we’re off to the Pratt Library, The Funk & Wagnall dictionaries. It states that the word is one peculiar to Baltimore, and that it means “a policeman’s Billy.” Also, that it comes from the Spanish, espanto, meaning “to threaten.”

Very well, why did the Baltimore police ever adopt the word Espantoon for what is known elsewhere as a policeman’s club, or nightstick?

Little Sir Echo answered; “Why?”

Gets Nowhere with Quest

None of the efficient research workers at the library could find out. Then I went outside and ask a policeman. He looked at me sympathetically and asked; “are you feeling all right buddy? We’ve had some hot weather, you know, and our hospitals are fine.”

That didn’t get me anywhere, so I sought out the help of one, Prof. Jacob H. HoHander of Johns Hopkins University, who not only knows Baltimore. But knows the word (Espantoon) backward and forward. Said he;

“I once wrote an editorial partly dealing with that subject. Of course, the word is of Spanish origin – but how did it ever reach Baltimore and become an expression in our police department is a complete mystery.”

Now for the Oxford English dictionary. Oh what have we here? Espantoon? No, but there’s Espontoon, with an “O” which is defined as a half pike – not a half pint, mind you – But a Half Pike as carried by infantry officers. Then the quotation from Southey;

“Capt. Lewis slipped and recovered himself by means of his Espontoon.”

Search goes on and on again

Well, all that in a question of spelling and derivation. It’s spelled Espantoon by the Baltimore Police Department, and that’s that.

Said George J Brennan, secretary to police Commissioner Stanton;

“It is true that the expression nightstick as applied to those implements carried by policeman is somewhat generally used elsewhere. To my knowledge Espantoon has been used by the Baltimore Police Department for the last 30 years. I have no idea as to its origin.”

(Robert F. Stanton, 1938-1943 – meaning his 30 years puts us at 1908-1913 – We have news articles going back to 1837 using the word Espantoon to describe a Baltimore officer’s Nightstick – So that is more than 100 years before Stanton’s time)

So there you are. The expression might have come to Baltimore with the early settlers as “Espontoon“ and then the spelling changed to “Espantoon.” (Imagine that, what would the grammar police have to say about that?)

On the other hand, the theory that some Spaniard brought it here holds good (possible), because the origin of the Spanish word – ESPANTO, to threaten – certainly applies to those Espantoon you see carried by our worldly Baltimore policemen.

Swagger stick helped him strut

Now for the British Marine and his swagger stick. He used it on the head of one of the policeman trying to help him. Is it an effective weapon?

No! It’s just something for “putting on the dog” when off-duty in the British Army. According to the Oxford English dictionary, you may call it either a swagger cane or swagger stick, and it is the short cane or stick carried by British soldiers when walking out, or going out on the town.

Originally it was a riding crop, but when the infantry took it up, it became a swagger stick. Its weight is slight, and it does not make an effective weapon.

Anyhow, the moral to it all is this, if you’re looking for trouble early in the morning, don’t try to use a swagger stick against an Espantoon. Not only is it bad etiquette, but it would be s bad for you all round. Espantoon! What a great word to stick in your brain and tumble out when you least expect it, like the song of the three little fishes.

Baltimore’s police Espantoon and how is used

Other cities call it a nightstick, but it’s got to be an Espantoon here. Where did the word come from? Experts are stumped. Some say it’s of Spanish origin; others English. Look it up and go crazy. Police are supposed to swing Espantoon only in “case of dire necessity.”

Espantoon History, Two years after the incorporation of the Baltimore Police Department in 1785 they appointed a police Chief and a high constable (then the Chief was known as a “Marshal”) at the time he toured the city caring a “mace”, and it was known as his “Badge of Office”. Oddly enough to this day our Espantoon is known as our “Badge of Authority”. In an 1843 the Sun paper report, a watchman had someone try to take his Espantoon by grabbing it during an arrest. From that report we know what it was called a “Mace” around the time we started carrying them in 1787, and that it was called an Espantoon some 56 years later in 1843. Now let’s look at the two terms… first a “Mace” often when we think of a Mace we think of a stick/club with some sort of axe blades, or a spiked ball on a chain attached to it… the Mace part of the spiked ball and chain or axe bladed weapon is actually the handle, the stick that the spiked ball, or axe blades attach to. Later the Mace is switched to Espantoon, which is exclusive to Baltimore Police, and derived from the “Spontoon”. A Spontoon, sometimes known by the variant spelling Espontoon (or as a Half-Pike), is a type of European “Pole-arm” that came into being alongside the “Pike”. The Spontoon was in wide use by the mid 17th century, 1650-1675’sh, and it continued to be used until the mid to late 19th century 1860/1890’s.

Unlike the Pike, which was an extremely long weapon (typically 14 or 15 feet), the “Spontoon” measured only 6 or 7 feet in overall length (that is to include the handle/mace and the attatched weapon, blade/maul etc. Generally, this weapon featured a more elaborate head than the typical Pike. The head or weapon of a Spontoon often had a pair of smaller blades on each side, giving the weapon the look of a military fork, or a “Trident”, but like a “Tomahawk”, it could also hold a “Blunt” object.

Italians might have been the first to use the Spontoon, and, in its early days, the weapon was used for combat, before later becoming a more symbolic item. After the musket replaced the Pike as the primary weapon of the foot soldier, the Spontoon remained in use as a Signaling weapon. Non-commissioned officers carried the Spontoon as a symbol of their rank, and used it like a Mace, in order to issue battlefield commands to their men. (Commissioned officers carried and commanded with swords, although some British Army officers used Spontoons at the Battle of Culloden.)

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Spontoon was used by Sergeants to defend the colors of a battalion or regiment from cavalry attack. The Spontoon was one of few Pole type weapons that stayed in use long enough to make it into American history. As late as the 1890s, the Spontoon could still be seen accompanying marching soldiers. Now days you may have seen the leader of a marching band carrying something like a Spontoon often called a Baton. They used these items to give their commands, as commands were given either verbally, through hand gestures, using a whistle or a Baton, or with a Mace in the military.

Lewis and Clark brought Spontoons on their expedition with the Corps of Discovery. The weapons came in handy as backup arms when the Corps traveled through areas populated by bears.

There were also spontoon-style axes. These used the same shaped blades mounted on the side of the weapon, and had a shorter handle.

Today, a spontoon (or Espontoon, as it is referred to in the manual of arms) is carried by the drum major of the U.S. Army’s Fife and Drum Corps, a ceremonial unit of the 3rd US Infantry Regiment (The Old Guard).

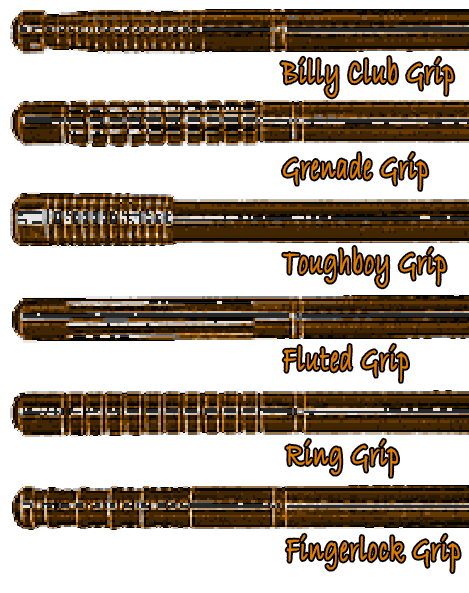

So if we take a look at the Spontoon, it is a Mace with a weapon end; the weapon can be sharp, blunt, or both. Now looking at the Espantoon, a mace with a blunt end, carved or turned onto it as opposed to being affixed or attached. The turned barrel head often mistaken for the handle on the nightstick but is actually the striking end of the Espantoon. Some say it was done this way on purpose, so people wouldn’t know it was the striking end, designed/disguised somewhat to look like a “Billy Club Handle”. The Spontoon’s weapon end would sometime be rounded, turned with ring grooves, other times a small marble sized ball would turned on the end, this was decorative, but also served a purpose in using it on pressure points, or for jabbing moves. All the popular handle designs were used on the striking end of the Spontoon/Mace to create the Espantoon. The turnings/carvings include, Ring Grips, Fluting and a combination of the two to form what is known as a, Grenade Grip, later came two more that are similar, they are the “Billy Club Grip”, or the “Tough-boy Grip”. There is only one final grip type, but we would never see it on an Espantoon, that is the “Fingerlock Grip” and it isn’t seen on the Espantoon, because it would lighten the striking end, and cause hard/sharp edges that would cause injuries that we don’t want. The “Fingerlock Grip” is most often found on the Truncheon, a Billy Club types weapon made for striking the subject, and less for jabs, arm bars, and wrist locks. While an Espantoon is made to strike or jab, it isn’t made to cause serious injury as much as it is meant for protection to the officer, by bringing the subject under control as fast as possible and with minimal injury. More often than not fear of the Espantoon would be enough, withdrawing it from its ring, or removing it from under the officer’s arm, would have a person quickly submit. In short we can see from old news reports in Baltimore, where we started with the “Mace”, in 1798, back then it was known as “The Badge of Office” later it went to the Spontoon, and finally the Espantoon. Add to this, the Espantoon, or Nightstick, to this day is known as a “Badge of Authority” and we know the Mace/Spontoon evilved into what is todsy known as the Espantoon.

Monadnock

Monadnock has been around with quality nightsticks, being considered as one of the leading Tactical Baton, Restraint and training aid supply companies, being one of the top choices of law enforcement professionals worldwide. For more than 50 years, Monadnock Tactical Batons has reflected the collective heritage, and expertise of a company focused on providing the highest quality gear equipment to police, military, and security professionals who depend on them every day, for self-protection and to protect those in the community that has been sworn to protect. The truncheon or Billy-club is an indispensable piece of police equipment, as primitive as a stick, and Monadnock Tactical Batons come in options to suit every professional need. Monadnock makes reliable batons for law officials, and tactical baton accessories suitable for riot control and crowd control. Monadnock equips law officers the world over, through academy training with soft training weapons, to actual self-defense weapons that will last a “lifetime” of work in the field.

More law enforcement officers choose to carry an American-made Monadnock expandable baton over any of the other competing brands. A collapsible baton makes for easier, and more discreet carrying, while a side handle baton gives more flexibility in grip and technique. Whether you need a telescopic baton, a stun baton, or an expandable steel baton, Monadnock makes it. Each police baton from Monadnock is made with the strongest materials, so you never have to worry – a Monadnock Baton is always ready when you need it.

![]()

LAY OFF BILLIES, POLICE ARE TOLD

The Sun (1837-1987); Dec 1, 1937;

pg. 15

LAY OFF BILLIES, .POLICE ARE TOLD

O’Dunne, In New Police School Talk, Calls Use Sign of Inefficiency – Judge Thinks Question Debatable Whether They Should Be Carried at all

“Lay off use of the nightstick,” Judge Eugene O’Dunne told policeman gathered yesterday at a regular session of the newly organize police school held in the Northern District Police Station.

Judge O’Dunne outline points for police to remember and preparing and presenting cases before the criminal court, in which he has been sitting this year. Warning the policeman against use of the nightstick, Judge O’Dunne said;

“It is a debatable question of policy whether officers should carry them at all. The London police, for the most part, go unarmed. I think it is a mistake in this country to judge everything by the customs of London. We are not Britishers.

Cities Cosmopolitan

“We live in cosmopolitan communities where nearly half of the population is foreign-born,” the judge continued, “in London only 3%, are not British-born. They have an inherent respect for law. It is a tradition with them. They Rivera authority. That sentiment does not prevail in America, at least not as it does over there…” Pointing out that most frequent use of the nightstick is on so-called drunks. Judge O’Dunne said; “ordinarily, an officer who uses the nightstick in such cases proves his inefficiency, nearly every use of the nightstick, in my judgment, warns a formal hearing before the Commissioner, as to the necessity or justification for it.

Viewed with Suspicion

“there are times when it may be justified, such as a riot, etc. But it is ordinarily viewed with grave suspicion, and any officer habitually reporting to it may be a fit subject for survey and retirement or dismissal in cases of use without full justification.”

Calling the story of the Baltimore police “one of honor and of romance.” Judge O’Dunne declared that the department must keep pace with changing times, and that this is an age of specialization, with a demand for specialist. He continues;

“the Police Department, which is one of the efficient agencies of government. Is not exempt from this inexorable demand. The criminal today is more scientific in his approach to crime than the police department which attempts to cope with him in the suppression of his activity and in his capture, trial and conviction after he has played his hand in an attempt to commit “the perfect crime.”

Commanding William P Lawson, Commissioner of police, on the existence of the police school, Judge O’Dunne said:

“I understand the promotion of the school and the burden of perpetuating it is due to magistrate Harry W. Allers, one of the young progressives of his age. More power to them. When he is as old as I am, he may be regarded as the “father of the new police system.” It is a title of which he may well be proud.”

Asserting that an error of education will be required to live down many prejudices associated with police work, Judge O’Dunne said “the idea that colleges or universities training cannot be helpful to those engaged in the ferreting out of crime, is one of those prejudices.”

Proves Falsity, Claim

“Jay. Edgar Hoover, head of the federal Bureau of investigation.” He continued, “has demonstrated the falsity of this idea. The results of his work are the answer to such challenges. He has on his staff men of the highest order of scientific training specialist in all branches, universities graduates of the higher order.”

Advocating a course in criminal law for all members of the Police Department, Judge O’Dunne gave the police pointers on their actions on the witness stand, what they should look for in preparing cases and some advice on what will be admitted in the court as evidence

Terms in Shortcut

In speaking of confessions, Judge O’Dunne said:

“I give it is my opinion, based on long observation, that forms of third-degree are too frequently resorted to, and later, too strenuously denied.

“There is a great temptation to get evidence from the prisoner, instead of hunting it up and running it down, by skill and industry.”

Judge O’Dunne, who opened his address by pointing to the work done by the department in preventing crime, was introduced by Commissioner Lawson

Baton Designs

As much as we like to call our “Nightsticks” and “Espantoon”, espantoons, come in different sizes shapes etc. and all fall under the category of a Baton, so the following article covers Batons, various sizes, shapes and names. Batons in common use by police around the world include many different designs, such as fixed-length straight batons, blackjacks, fixed-length side-handle batons, collapsible straight batons, and other more exotic variations. All of these different types of batons have their advantages, and disadvantages.

The design and popularity of specific types of baton have evolved over the years and are influenced by a variety of factors. These include inherent compromises in the dual (and competing) goals of control effectiveness and safety (for both officer and subject). They have three basic lengths in your standard Espantoon/Nightstick they are the “Nightstick” about 24 to 26 inches, the “Daystick” 12 to 14 inches, and the “Mounted Longstick/Horseback Stick” these ranged from 36 to 38 inches. Each of these three sticks were often custom made and could be a little longer or shorter than the norm. These different sizes were used for different shifts, and different assignments, and just as they were more comfortable to use a Daystick for dayshift and a nightsticks for nightsticks, it was necessary for the Mounted to use a Longstick; some officers needed a stick a little longer or shorter than the norm. These were and still are used to defend against attack, and as such require differences to adjust them to better fit the officer’s needs. We hope this page will show the different sticks used and in use around the world and in the Baltimore Police department.

Spontoon

A Spontoon, sometimes known by the variant spelling espontoon (or as a half-pike), is a type of European pole-arm that came into being alongside the pike. The spontoon was in wide use by the mid 17th century, and it continued to be used until the mid to late 19th century.

Unlike the pike, which was an extremely long weapon (typically 14 or 15 feet), the spontoon measured only 6 or 7 feet in overall length. Generally, this weapon featured a more elaborate head than the typical pike.

The head of a spontoon often had a pair of smaller blades on each side, giving the weapon the look of a military fork, or a trident.

Italians might have been the first to use the spontoon, and, in its early days, the weapon was used for combat, before it became more of a symbolic item.

After the musket replaced the pike as the primary weapon of the foot soldier, the spontoon remained in use as a signalling weapon. Non-commissioned officers carried the spontoon as a symbol of their rank and used it like a mace, in order to issue battlefield commands to their men. (Commissioned officers carried and commanded with swords, although some British Army officers used spontoons at the Battle of Culloden.)

During the Napoleonic Wars, the spontoon was used by sergeants to defend the colors of a battalion or regiment from cavalry attack. The spontoon was one of few pole weapons that stayed in use long enough to make it into American history. As late as the 1890s, the spontoon could still be seen accompanying marching soldiers.

Lewis and Clark brought spontoons on their expedition with the Corps of Discovery. The weapons came in handy as backup arms when the Corps traveled through areas populated by bears.

There were also spontoon-style axes. These used the same shaped blades mounted on the side of the weapon, and had a shorter handle.

Today, a spontoon (or espontoon, as it is referred to in the manual of arms) is carried by the drum major of the U.S. Army’s Fife and Drum Corps, a ceremonial unit of the 3rd US Infantry Regiment (The Old Guard).

The spontoon being the wooden portion of the weapon, the pike or axe tool head was made of a metal or even stone that was added to the spontoon – these would eventually be removed and the spontoon cut down in length from around 6 feet in length to just 2 ft. Often these Spontoons would have a wood carved head on the striking end, giving us more of a Billy Club, Baton, that would become what is known in Baltimore as the Espantoon. As is described elsewhere on this page, the Espantoon is a combination of many of these hand to hand fighting weapons, and in Baltimore you will still see the Espantoon carried by our police, as basic and primal as a stick, could be the difference between an officer going home at the end of the shift.

Mace

A mace is a blunt weapon, a type of club or virge that uses a heavy head on the end of a handle to deliver powerful blows. A mace typically consists of a strong, heavy, wooden or metal shaft, often reinforced with metal, featuring a head made of stone, copper, bronze, iron, or steel.

The head of a military mace can be shaped with flanges or knobs to allow greater penetration of plate armor. The length of maces can vary considerably. The maces of foot soldiers were usually quite short (two or three feet, or seventy to ninety centimeters). The maces of cavalrymen were longer and thus better suited for blows delivered from horseback. Two-handed maces could be even larger.

Maces are rarely used today for actual combat, but a large number of government bodies (for instance the British House of Commons, the U.S. Congress), universities and other institutions have ceremonial maces and continue to display them as symbols of authority. They are often paraded in academic, parliamentary or civic rituals and processions.

Chemical Mace an interesting name for it, basically a chemical designed to stop someone the way an actual mace would, but less or no blood… The actual Mace is a blunt weapon, a type of Club or Virge that uses a heavy head on the end of a handle to deliver powerful blows. A Mace typically consists of a strong, heavy, wooden or metal shaft, often reinforced with metal, featuring a head made of Stone, Copper, Bronze, Iron, or Steel with a Pike or Axe attached to the end… removing the Pike or Axe you still have a Mace.. So a Mace is basically a Pike or Axe handle. Same with the Spontoon as described below – The head of a military Mace can be shaped with Flanges or Knobs to allow greater penetration of plate armor. The length of a Mace can vary considerably. The Mace of foot soldiers were usually quite short (two or three feet, or 24 to 36 inches). The Maces of cavalrymen were longer and thus better suited for blows delivered from horseback. Two-handed Maces could be even larger. Maces are rarely used today for actual combat, but a large number of government bodies (for instance the British House of Commons, the U.S. Congress), universities and other institutions have Ceremonial Maces and continue to display them as symbols of authority. They are often paraded in academic, parliamentary or civic rituals and processions. It is from the Mace that the Spontoon and then Espantoon evolved, and best of all, the old metal or stone pike became part of the wooden Mace/Spontoon as it was carved or turned into the stick, known as the Barrel Head (The striking end of the Espantoon).

![]()

Espantoon

Sheila S Nyka

The Sun (1837-1987);

Jul 19, 1979;

pg. A16

Espantoon

Sir: In his witty and amusing July 19 page A16 article, Girard Ordway does not suggest an origin for the word “espantoon.” Is it not probable that this is derived from the Spanish verb “espan·tar” which, according to my dictionary, means “To frighten, terrify, chase You”? Shella S. Nyka Baltimore.

Courtesy Mark Frank

1960 Carl Hagen Stick

From Sun Article Policeman’s Bestfriend

![]()

Local matters (Police Officer Shot)

Baltimore Sun 5 January 1858

pg 1

Police Officer Shot – John Winkleman, a police officer attached to the Southern District Force, was essentially shot in the thigh a few evenings ago since (2 January 1858) by his revolver which exploded in his pocket. He was thoughtlessly whirling a stick around between his fingers, when the bludgeon struck the hammer of the weapon, causing it to discharge its load into his thigh. The ball was extracted by a surgeon.

Several things to note, one use of the word “Bludgeon” – A bludgeon refers to a heavy club used as a weapon. This was 1858 and I have articles before this time calling it an Espantoon, so this just might be the author, but he did say Twirling the stick between his fingers, So we have them twirling a stick as far back as 1858. Now in reference to the gun, in the 1800’s they carried in their pocket, some used a pocket holster, many were injured, even killed by accidental discharge, looking at the wording, the writer says, “causing it to discharge its load into his thigh” this is singular, as its not one of it’s loads, a round etc. this was a single shot weapon. Also vary common of our early police to carry. This being a time when the department didn’t issue a firearm. So this one little article is full of history, and information.

Nightstick

Where the Word Comes From