Nicholas Biddle

The Baltimore Riots 1861

Nick Biddle and the First Defenders

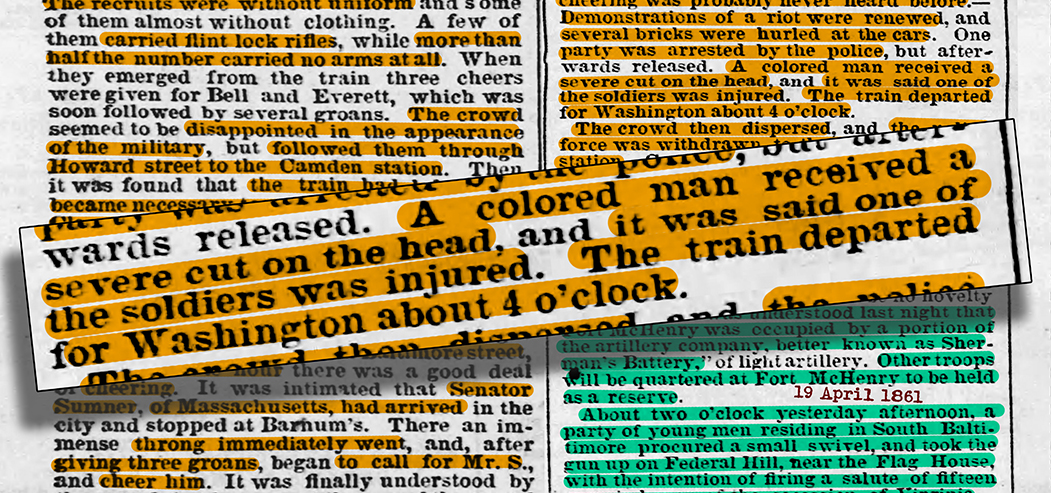

18 April 1861 after a day of screaming, hollering, yelling, cursing, throwing bricks, or portions of cobblestones that put men in the hospital, fighting for their lives. But, it wasn't enough, and it certainly wasn't the end of it, in fact, they were just warming up, for worse things to come the following day.

Click Here to View 18 April 1861 Newspaper Article

19 April 1861, Southern sympathizers attacked the Massachusetts 6th Regiment Infantry, screaming, hollering, yelling, cursing, throwing bricks, or pieces of cobblestone, and that was the least of their troubles. Not long after bricks were hurled in the direction of the soldiers, the report of a handgun was heard to have rung out in the area. Before long, shots were heard coming from both sides. Later the military denied having fired on the crowd, but these shootings were witnessed by Marshal Frey, Mayor Brown and many others. Four soldiers were killed in what has since become known as the Pratt Street Riots, or the Baltimore Riot of 1861 or the Pratt Street Massacre. [New York Public Library]

Click Here to View 19 April 1861 Newspaper Article

Click HERE to Hear Audio

The first man to shed blood during the Civil war was an escaped slave by the name of Nicholas Biddle from Pottsville, PA. Due to his having escaped a life of slavery very little is known of Mr. Biddle's life. From what we have learned he was born to slave parents in Delaware circa 1796. At some point, he escaped slavery and settled in Pennsylvania. It was common practice for escaped slaves to change their names to avoid capture, two stories told of Nicholas Biddle.

According to one historian's findings; Biddle escaped to Philadelphia and got a job as a servant for Nicholas Biddle, the wealthy financier, and president of the Second Bank of the United States. In this story, the former slave and the financier traveled to Pottsville for a dinner meeting of entrepreneurs and industrialists at nearby Mount Carbon to celebrate the first successful operation of an anthracite-fueled blast furnace in America. The servant remained in Pottsville to live. Another account is that Biddle relocated from Delaware directly to Pottsville and became a servant at the hotel where the aforementioned celebratory dinner was held, at which he met the famous Biddle.

In any event, we know that he adopted the name of the prominent Philadelphian, and by 1840 Nicholas Biddle was residing in Pottsville. He worked odd jobs to earn a living, including street vending, selling oysters in the winter and ice cream in the summer. The 1860 U.S. census lists his occupation as "porter."

Biddle befriended members of a local militia company, the Washington Artillerists, and attended their drills and excursions for the next 20 years. The company members were fond of Biddle and treated him as one of their own, and although African Americans were not permitted to serve in the militia, they gave him a uniform to wear.

At the outbreak of the Civil War and the fall of Fort Sumter on April 15, 1861, President Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteers to serve for three months to suppress the insurrection in the South. Unlike other antebellum militia units, the Washington Artillery had maintained a state of readiness and was among the first companies to respond to Lincoln's call to arms.

Two days later, the Washington Artillerists departed Pottsville by train to enter the war, along with 65-year-old Nicholas Biddle, who served as an aide to the company's commanding officer, Captain James Wren.

On April 18, five companies, numbering some 475 men, were sworn in at Harrisburg and mustered into the service of the United States. That is, all except for Nicholas Biddle, who as an African American was prohibited from serving in the U.S. Army.

The soldiers left on an emergency order to defend Washington, DC against a rumored Confederate attack. But in 1861, there was no continuous passenger rail service through Baltimore, and when the soldiers detained in the largest city in the slave state of Maryland, they encountered a hostile mob of pro-Southern sympathizers.

As the companies marched to meet their trains, members of the mob taunted the soldiers and hurled bricks and stones. Biddle, a black man in uniform, was an easy target. Someone threw a brick, striking Biddle in his head and knocking him to the ground. This made Nicholas Biddle the first casualty caused by hostile action in the Civil War.

The wound was grave enough that it exposed his bone. It was reportedly the first and most serious injury suffered that day, and he bore the scar the rest of his life.

An anxious President Lincoln learned of the arrival of the five Pennsylvania companies and of their treacherous passage through the mob at Baltimore. The morning after they arrived in Washington, Lincoln personally thanked each member of the five companies and singled out the wounded for special recognition.

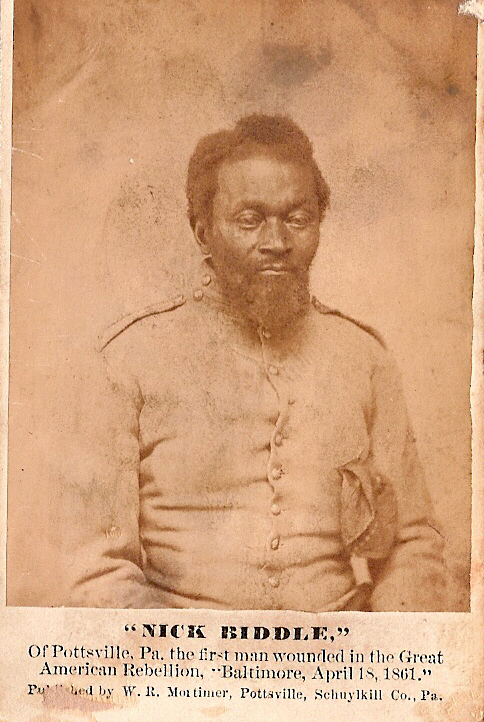

After his military service, Biddle returned to relative obscurity in Pottsville, where he eked out a living performing odd jobs. In the summer of 1864, he appeared at the Great Central Fair in Philadelphia, where photographs of him in a Washington Artillerists uniform, captioned "the first man wounded in the Great American Rebellion," were sold to raise funds for the relief of Union soldiers. In the end, however, Biddle was forced to solicit alms to make ends meet. He died destitute in 1876 without even enough money to cover his burial expenses. Surviving members of the Washington Artillerists and the National Light Infantry each donated a dollar to purchase a simple headstone for him, and they had it inscribed: "In Memory of Nicholas Biddle, Died Aug.2, 1876, Aged 80 years. His was the Proud Distinction of Shedding the First Blood in the Late War for the Union, Being Wounded while marching through Baltimore with the First Volunteers from Schuylkill County, 18 April 1861. Erected by his Friends in Pottsville."

Throughout the remainder of his life, Biddle retained unpleasant memories of his perilous journey with the Washington Artillerists through Baltimore. Although it garnered him the "proud distinction of shedding the first blood," he was often heard to remark "that he would go through the infernal regions with the artillery, but would never again go through Baltimore."

![]()

This card/photo served as a remarkable testament to the bravery and sacrifice of Nick Biddle, who was recognized as the first man wounded during the significant event that came to be known as the Great American Rebellion. By proudly wearing his uniform and attending various fairs and events, Biddle aimed to commemorate his role in history and inspire others with his story. The fact that this card/photo was printed by W.R. Mortimer of Pottsville, Schuylkill Co., Pa., adds an intriguing detail about the local history.![]()

Click the above article, or HERE to see full article

Click the above article, or HERE to see full article

The violence erupted when a mob of southern sympathizers attacked a group of Union soldiers passing through the city on their way to Washington, DC. The tragic events that took place on Howard Street on the 18th and Pratt Street on the 19th, leading to death and serious injury, marked a turning point in the nation's history, highlighting the deep divisions in our country, and serving as a grim precursor to the widespread violence and bloodshed that would soon engulf the entire country into a Civil War.

![]()

Nicholas Biddle and the First Defenders

By Ronald S. Coddington

18 April, 2011

On the afternoon of April 18, 1861, Nick Biddle was quietly helping his unit, the Washington Artillery from Pottsville, Pa., set up camp inside the north wing of the Capitol building. The day before, he was almost killed.

Biddle was a black servant to Capt. James Wren, who oversaw the company of about 100 men. On April 18 the Washington Artillery had been one of several Army outfits, totaling about 475 men, heading through Baltimore en route to Washington, D.C., in response to President Lincoln’s call for 75,000 troops to put down the Southern rebellion.

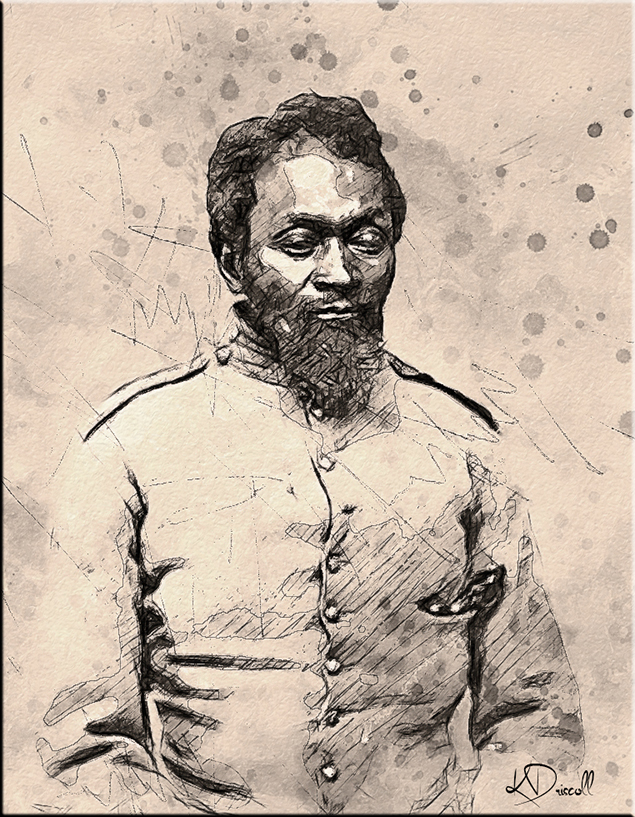

Collection of Thomas Harris Nicholas “Nick” Biddle by William R. Mortimer of Pottsville, Pa., circa 1861 - Thousands of pro-Confederate Baltimoreans turned out to meet them at the city’s northern train station. (Another group, 45 regular Army soldiers from the Fourth Artillery en route from St. Paul, Minn., to Fort McHenry, also disembarked.) The crowd expressed disappointment in the non-military look of some of the volunteers, who hailed from eastern Pennsylvania coal-mining country. They “were not more than half uniformed and armed, and presented some as hard-looking specimens of humanity as could be found anywhere,” reported the Baltimore Sun. Most of the men carried their own revolvers, while a few toted antiquated flintlocks. A select group carried state-issued modern muskets but had no gunpowder for them.

Captain Wren, Biddle and the others were aware of Baltimore’s pro-secession sentiment and expected trouble. One volunteer reportedly asked Biddle if he was afraid to face rowdy “plug-uglies” and jokingly warned, “They may catch you and sell you down in Georgia.” Biddle replied in dead earnest that he was going to Washington trusting in the Lord and that he wouldn’t be scared away by the devil himself — or a bunch of thugs.

The Pennsylvanians formed a line and prepared to march through Baltimore to another station, where they could catch a Washington-bound train. The regulars would lead the way. The line started and moved rapidly, shielded from the abusive mobs by policemen stretched 10 paces apart. A private recalled the “Roughs and toughs, ‘longshoremen, gamblers, floaters, idlers, red-hot secessionists, as well as men ordinarily sober and steady, crowded upon, pushed and hustled the little band and made every effort to break the thin line.”

The mob derided the volunteers and cheered for Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy. Some aimed their abuse at Biddle. Capt. Wren remembered, “The crowd raised the cry, ‘Nigger in uniform!’ and poor old Nick had to take it.”

Around the halfway point of the journey, the regular troops split off and marched to Fort McHenry, leaving the Pennsylvanians alone. “At this juncture the mob was excited to a perfect frenzy, breaking the line of the police and pushing through the files of men, in an attempt to break the column,” wrote one historian. The boldest in the crowd spit, kicked, punched and grabbed at the coattails of the volunteers.

As the Pennsylvanians neared the station, rioters chucked cobblestones and jagged pieces of broken brick. The bombardment intensified as the volunteers arrived at the station and began to board the cars. Suddenly a chunk of brick struck Biddle in the head and left a deep, profusely bleeding cut. He managed to get on the train as the mob climbed on top of the cars and jumped up and down on the roofs. Biddle found a comfortable spot, wrapped his head in a handkerchief, and then pulled his fatigue cap close over the wound.

When the Pennsylvanians finally arrived in Washington that evening, they received a very different reception, as enthusiastic crowds welcomed them as saviors. They occupied temporary barracks in the north wing of the Capitol. One officer remembered that, when Biddle entered the rotunda of the building, “He looked up and around as if he felt that he had reached a place of safety, and then took his cap and the bloody handkerchief from his head and carried them in his hand. The blood dropped as he passed through the rotunda on the stone pavement.”

From Heber S. Thompson’s The First Defenders, scanned by openlibrary.org Front and back of a commemorative medal approved by an act of the Pennsylvania legislature in 1891 and issued to surviving members of the First Defenders.

A grateful President Lincoln later greeted the Pennsylvanians. He reportedly shook hands with Biddle and encouraged him to seek medical attention. But Biddle refused. He preferred to remain with the company. At the time some considered Biddle’s blood the first shed in hostility during the Civil War.

The House of Representatives later passed a resolution thanking the Pennsylvanians for their role in defense of the capital. The volunteers came to be known as the “First Defenders” in honor of their early response to Lincoln’s call to arms.

Sources: The Baltimore Sun, April 19, 1861; James M. Guthrie, “Camp-Fires of the Afro-American”; Samuel P. Bates, “History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5,” Vol. 1; Heber S. Thompson, “The First Defenders”; Weekly Press (Philadelphia, Pa.), March 24 and July 21, 1886; John D. Hoptak, “A Forgotten Hero of the Civil War,” Pennsylvania Heritage, Spring 2010; W.W. Munsell & Co., “History of Schuylkill County, Pa.”; Lowell (Massachusetts) Daily Citizen and News, April 20, 1870; U.S. House of Representatives, Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States; Weekly Miners’ Journal (Pottsville, Pa.), Aug. 11, 1876; Herrwood E. Hobbs, “Nicholas Biddle,” Historical Society of Schuykill County, 1961.

Ronald S. Coddington is the author of “Faces of the Civil War” and “Faces of the Confederacy.” His forthcoming book profiles the lives of men of color who participated in the Civil War. He writes “Faces of War,” a column in the Civil War News.

![]()

Nicholas Biddle: The Civil War’s First Blood

Just days after Fort Sumter, a pro-Confederate mob in Maryland turned ex-slave Nicholas Biddle into the war's first casualty.

By

“N—— in Uniform! N—— in Uniform!” screamed the agitated Baltimore crowd of Southern sympathizers. They had been angry enough when Pennsylvania militiamen had detrained at Bolton Street station and began marching down Eutaw Street toward Camden Station on April 18, 1861, but when they saw Nicholas Biddle, an African American in uniform who was treated as an equal by his white comrades, their blood lust only increased and their calls grew louder. “Poor Nick had to take it” as the mob closed in like “wild wolves,” Captain James Wren, Biddle’s commander, later recorded.

Biddle soon became the target of more than just oaths, as salvos of bricks pried loose from the streets began to fly through the air. One struck Biddle in the head, knocking him to the ground and leaving a wound that reportedly exposed bone.

Many Pennsylvanians present that day believed Biddle was the first person to die in the Civil War at the hands of an enemy combatant. Regardless of who shed first blood in what would be the bloodiest of all America’s wars, it seems strange that Biddle remains an overlooked and almost entirely forgotten figure in the Civil War’s rich history.

At the time, however, Biddle received the attention of Abraham Lincoln as the president visited the militiamen being billeted at the U.S. Capitol on April 19. Lincoln wanted to thank the men who had arrived to defend Washington only four days after he called for 75,000 volunteers to quell the rebellion that began with the attack on Fort Sumter on April 12.

The president learned the Pennsylvanians had been attacked while traveling through Baltimore en route to the capital. Private Ignatz Gresser, a native of Germany, suffered from a painful ankle wound, and Private David Jacobs had a fractured left wrist and a few broken teeth. But it was the frail 65-year-old Biddle, wearing the uniform of the Washington Artillery, his head wrapped in blood-soaked bandages, who especially caught Lincoln’s attention. Biddle refused the president’s advice to seek medical attention, insisting that he preferred to remain with his company.

The Pennsylvanians were the first of the volunteers to arrive in the District of Columbia and would thus go down in history as the “First Defenders.” Their Baltimore injuries occurred as the men arrived for the final leg of their journey from Pennsylvania to Washington. The entire Baltimore police force had been summoned to escort the volunteers through the streets, but even the police had a difficult time controlling the raucous crowd of 2,000, which jeered the anxious militiamen while hurrahing for Jefferson Davis and the Southern Confederacy.

As the volunteers arrived at Camden Station, they were pelted with stones, bricks, bottles, and whatever else the local mob could reach; some were even clubbed or knocked down by a few well-landed punches. A few bolder Confederate sympathizers lunged at the unarmed Pennsylvanians with knives and drawn pistols. First Defender Heber Thompson wrote that one man was caught dumping gunpowder on the floor of one of the train cars “in the hope that a soldier carelessly striking a match in the darkened interior... might blow himself and his comrades to perdition.” For the idealistic volunteers from Pottsville, Allentown, Reading, and Lewistown, the ordeal quickly erased any romanticized notions of soldiering they might have had.

BIDDLE’S INJURIES WERE THE MOST SERIOUS, an irony considering he wasn’t technically a soldier since the federal government would not muster him in because of his race. Biddle, however, had willingly marched off to war as the orderly of Captain Wren, the Washington Artillery’s commanding officer. He had been a part of the company since its founding in 1840, and because the other members of the unit regarded him so highly, they gave him a uniform.

Little is known about Biddle’s life, except that he was born a slave in Delaware about 1796 and later escaped. But exactly when he slipped the chains of human bondage is not known. Nor is it known where Biddle first settled in Pennsylvania. One account has him settling in Philadelphia, where he was possibly taken in by abolitionists. He reportedly soon found work as a servant in the lavish home of Nicholas Biddle, the wealthy financier and longtime president of the Second Bank of the United States, whose name the escaped slave adopted as his own.

According to this account, Biddle, along with his servant, traveled to the Schuylkill County seat of Pottsville in January 1840 for a celebratory dinner at the Mountain House hotel in the nearby village of Mount Carbon. Along with 80 industrialists and capitalists, they celebrated the success of William Lyman’s Pottsville Furnace, the first in the United States to smelt iron by an anthracite-fired blast furnace continuously for 100 days. For whatever reason, the servant Biddle remained behind in Pottsville when his employer returned to Philadelphia.

Another story, perhaps more plausible, has the escaped slave settling in Pottsville itself and becoming a servant at the Mountain House hotel, where he was employed during the January 1840 dinner. If this is true, then, as Schuylkill County historian Herrwood Hobbs wrote, “something of financier Biddle rubbed off on him,” and he adopted the capitalist’s name.

Whatever the truth, by 1840, Biddle had made Pottsville his home, taking up residence in a modest dwelling on Minersville Street. He took an active interest in the city’s two militia companies, the National Light Infantry and the Washington Artillery, whose members he quickly befriended. When news of President Lincoln’s call to arms spread throughout the North in April 1861, both the National Light Infantry and the Washington Artillery were quick to tender their services. Departing Pottsville on April 17, 1861, they reached Harrisburg late that evening. The following morning, the two companies, along with the Ringgold Light Artillery from Reading, the Logan Guards from Lewistown, and the Allen Infantry of Allentown, boarded the North Central Railroad and began their journey to Washington via Baltimore. Before setting out from the Pennsylvania capital, the soldiers of the five companies took the oath of allegiance and were all sworn in as soldiers of the United States. All of them except Nicholas Biddle, of course.

The term of service for the initial 75,000 Northern volunteers—including those in the ranks of the First Defender companies—was for three months, and in late July 1861, the soldiers were mustered out. But most of the First Defenders were quick to reenlist, this time “for three years, or the course of the war.” Almost to a man, the National Light Infantry became Company A of the 96th Pennsylvania Infantry, while most members of the Washington Artillery reenlisted into the ranks of Company B, 48th Pennsylvania Infantry, with James Wren remaining as captain. Nick Biddle, however, did not accompany Wren when the 48th left Schuylkill County in September 1861. He remained in Pottsville, still nursing the painful head wound he had suffered in Baltimore.

Biddle spent the rest of his life in Pottsville, performing odd jobs, until he began to suffer from rheumatism. As he grew older and more infirm, he couldn’t perform any labor. Despite being a wounded veteran, he could not draw a Federal pension because he had never mustered in. Impoverished in his final years, he walked the streets of Pottsville seeking charity.

Pottsville’s leading newspaper, The Miners’ Journal, appealed to the community for help.

“If poor old Nick Biddle calls on you with a document, as he calls it, don’t say you are in a hurry and turn him off, but ornament the paper with your signature and plant a good round sum opposite your name,” the paper implored. “Nick has been a good soldier and now that he is getting old and feeble, he deserves the support of our citizens.”

Nicholas Biddle died in his home on August 2, 1876, at the age of 80. Before he died, the proud figure claimed he had enough money saved up in the bank for a proper funeral and burial, but upon his death, it was discovered that there was not a penny to his name.

The surviving veterans of the Washington Artillery and the National Light Infantry once again answered the call. Agreeing to pay for the costs, they arranged Biddle’s funeral, which took place just two days after his death. A large crowd gathered in front of Biddle’s home and then, as a drum corps played, began the solemn procession up Minersville Street to the “colored burying ground” adjacent to the Bethel A.M.E. Church.

AFTER THE SERMON AT THE CEMETERY, a number of uniformed First Defenders carried the simple coffin to the burial site and laid Nicholas Biddle to rest. The surviving First Defenders contributed $1 each to pay for a tombstone, upon which was inscribed:

In Memory of Nicholas Biddle, who died on August 2, 1876, Aged 80 Years. His Was the Proud Distinction of Shedding the First Blood In the Late War For the Union, Being Wounded While Marching Through Baltimore With the First Volunteers From Schuylkill County 18 April 18, 1861. Erected By His Friends In Pottsville.

On April 18, 1951, the 90th anniversary of the First Defenders’ famed march through Baltimore, the people of Pottsville dedicated a bronze plaque for the Civil War Soldiers’ Monument in Garfield Square. “In Memory of the First Defenders And Nicholas Biddle, of Pottsville, First Man To Shed Blood In The Civil War. April 18, 1861,” it reads.

Since then, awareness of Biddle's contribution to the Civil War has almost completely vanished, and shamefully, vandals have destroyed his tombstone.

John D. Hoptak works as a ranger at Antietam National Battlefield. He is the author of First in Defense of the Union: The Civil War History of the First Defenders, and maintains a Web site on the 48th Pennsylvania at 48thpennsylvania.blogspot.com.

Click HERE for the original page

![]()

The Grave of Nick Biddle:

By Chaplain James M. Guthrie

The grave of Nick Biddle a Mecca should be

To Pilgrims, who seek in this land of the free

The tombs of the lowly as well as the great

Who struggled for freedom in war of debate;

For there lies a brave man distinguished from all

In that his veins furnished the first blood to fall

In War for the Union, when traitors assailed

Its brave “First Defenders,” whose hearts never quailed.

The eighteenth of April, eighteen-sixty-one,

Was the day Nick Biddle his great honor won

In Baltimore City, where riot ran high,

He stood by our banner to do or to die;

And onward, responsive to liberty’s call

The capital city to reach ere its fall,

Brave Biddle, with others as true and as brave,

Marched through with wildest tempest, the Nation to save.

Their pathway is fearful, surrounded by foes,

Who strive in fierce Madness their course to oppose;

Who hurl threats and curses, defiant of law,

And think by such methods they might overawe

The gallant defenders, who, nevertheless,

Hold back their resentment as forward they press,

And conscious of noble endeavor, despise

The flashing of weapons and traitorous eyes

Behold now the crisis—the mob thirsts for blood:-

It strikes down Nick Biddle and opens the flood—

The torrents of crimson from hearts that are true—

That shall deepen and widen, shall cleanse and renew

The land of our fathers by slavery cursed;

The blood of Nick Biddle, yes, it is the first,

The spatter of blood-drops presaging the storm

That will rage and destroy till Nation reform.

How strange, too, it seems, that the Capitol floor,

Where slaveholders sat in the Congress of yore,

And forged for his kindred chains heavy to bear

To bind down the black man in endless despair,

Should be stained with his blood and thus sanctified;

Made sacred to freedom; through time to abide

A temple of justice, with every right

For all the nation, black, redman, and white

The grave of Nick Biddle, though humble it be,

Is nobler by far in the sight of the free

Than tombs of those chieftains, whose sinful crusade

Brought long years of mourning and countless graves made

In striving to fetter their black fellowmen,

And make of the Southland a vast prison pen;

Their cause was unholy but Biddle’s was just,

And hosts of pure spirits watch over his dust.

Click HERE for the original page

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to Honor the fine men and women who have served with Honor and Distinction at the Baltimore Police Department.

Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll