First Dead 1861

The Civil War's First Dead

“I’ll eat when I’m hungry and drink when I’m dry, and if the Johnnies don’t kill me, I’ll live till I die.” With 12 Baltimoreans Killed In The Bloody Pratt Street Riot

With 12 Baltimoreans Killed In The Bloody Pratt Street Riot

The most significant action of the Civil War may have occurred in Baltimore on 19 April 1861 during the Pratt Street Riots, which directly caused 17 known deaths and at least 50 injuries and seven recorded arrests, which are now known as the first deaths of the Civil War. Many believe this attack on the union army was at least in part allowed by the Mayor and Police Commissioner at the time, as they were confederate or southern sympathizers one or both being part of the Know Nothing a political party in the US, prominent from 1853 to 1856, that was antagonistic toward Roman Catholics and recent immigrants and whose members preserved its secrecy by denying its existence.

Most of the fighting took place along President Street from near the Harbor North to Pratt Street along Pratt St., West to Light Street the violent action lasted from about 11 AM to 12:45 PM and mostly involved 220 New England Militiamen, some of whom carried and fired muskets, and a mob of Baltimore civilians including a New Maryland Militiamen out of uniform that was variously reported to number anywhere between 250 and 10,000 (more on those number in this report) and which fired a few pistols but fought mainly by grappling, and or hurling paving stones.

Of the 600 or so officers and men of the 6th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, a volunteer militia, who passed from the President Street Station to Camden Station in route to Washington, four were killed and about 35 wounded. The dead soldiers all of enlisted rank, are Addison O Whitney, Luther C Ladd, Charles A Taylor, and Sumner H Needham. The last named died with little resistance in Baltimore Hospital about a week after the riots and during a 19th Century style operation on his fractured skull.

Of the 10,000 unarmed Pennsylvania Militiamen and the 100 additional members of the six Massachusetts including the Regiment Band who arrived at the same time none made it through the mob around President Street Station on this journey but only one died of injuries sustained here. He was George Leisenring, who also succumbed about a week later, after he returned to Philadelphia.

Many Baltimoreans were wounded, and 12 were killed – James Carr, William R. Clark, Robert W. Davis, Sebastian Gill, Patrick Griffiths, John McCann, John McMahon, Francis Maloney, William Maloney, Philip S. Miles, Michael Murphy, and William Reid.

At the time and off and on ever since leading Baltimoreans were and have been the most outraged by the death of Mr. Davis a 36-year-old Drygoods Merchant and Semi-innocent bystander he may have cheered for the Confederacy but he did not join the fighting, and was shot by someone on the 6th Massachusetts trained shortly after it left Camden Station. He cried, “I am killed!” as he fell and the next day a Baltimore coroner’s jury decided that he had been ruthlessly murdered. By one of the military Mr. Davis’s funeral was elaborate but his murder, if that term is strictly accurate was never named, charged, or prosecuted.

Two of the dead civilians Patrick Griffiths and William Reid were described as boys (which at the time might have meant that they were black, adult males white or black with low wage jobs, or that they may have been very young, probably poor white males). Patrick Griffith was employed on an Oyster’s Sloop that was tied up near Pratt and Light Street. William Reid was employed by a Pratt Street establishment described only as of “The Greenhouse” and was shot through the bowels while looking on from the business door.

The ages addressed occupation specifically circumstances of death and last rites of the other Baltimore casualties have apparently never been recorded although those who fell in the Pratt Street riots turned out to be the first fatality victims of a hostile action in the Civil War (no one was killed during reaction which had ended four days earlier at Fort Sumter South Carolina)

The most thorough contemporary accounts of the riots in Baltimore newspapers state that the police arrested “great numbers” afterward. Only seven were apparently ever named anywhere though – Mark Hagan and Andrew Eisenbreeht, charged with “assaulting an officer with the brick” Richard Brown and Patrick Collins “throwing bricks creating a riot” William Reid “severely injuring a man with a brick” J Friedenwald, “assaulting an unknown man” and Lawrence T Erwin, “throwing a brick on Pratt Street” these seven constituted a nether Civil War first

The troops from Massachusetts and Pennsylvania were responding to Abraham Lincoln’s April 15 call for volunteers, and many Baltimoreans in slave-holding Maryland interpreted that to be an effort to recruit an army to invade such succeeding “sister states” as Virginia. A Confederate Army recruitment office flourished at Marsh Market: a pro-secession mob of about 800 had roamed Charles Street on the night of April 18, and more than one Negro had recently been flogged for daring to cheer the Republican President in public.

So the Baltimoreans in the Pratt Street riots were as much pro-Southern as they were simply pro Maryland or simply outraged by the alleged violation of State sovereignty by another State’s Militia (An idea suggested in “ Maryland! My Maryland!” the official state song that was inspired by and written shortly after the riots by writer Randall, a native Baltimorean English teacher then in New Orleans).!

And so the seven Baltimoreans arrested turned out to be the first Civil War partisans of either side who suffered official legal action for their pains. Of them boldly Lawrence T Erwin was convicted and “held for sentence” so far as contemporary accounts, histories and memories reveal. His sentence, if any, is also unrecorded.

One history of Baltimore Police Department explains that “it was useless to arrest men when not an officer could be spared to put them in jail.” It seemed too, that although the department had been reorganized about a year earlier under Marshal George P. Kane to rid it of corrupt “Know Nothing” political elements, it had no patrol wagons in 1861, and since the main body of police detailed to maintain order during the militia’s passage was either a half mile away at Camden Station or in route to the scene of the fighting door and most of the writing, it is perhaps remarkable that as many as seven arrests were made.

Why the main body of police was at the end of the troops projected route, instead of at its beginning, is still something of a mystery. The record collection of the riots that was published 19 years after the events by George William Brown, who was mayor in 1861, lays part of the blame on the management of the P.W. & B. be railroad the company failure to answer marshal Kane’s repeated telegrams that ask how many troops were in route to the Pres. Street location and when: so by 1030 on the morning of April 19, the police could do nothing better than send their main body – “a strong force” – the Camden Station.

Such action was proper, one infers from Mayor Brown’s account, even though a large crowd had assembled at both stations as early as 9 AM and even though the secessionist flag – a circle of white stars on a field of blue – was displayed by the throng and Pres. Street station. Passers to arrive from the North won the P.W. & B than customarily stayed one the cars and Pres. Street station if they were bound for Washington, and the cars were hauled one by one and by four force teams, to Camden station, where the passengers got off and boarded Baltimore and Ohio trains to continue to national capital. “As the change of cars occurred at this point,” a Police Department history published in 1888 remarks, “it was here that the attack was feared.”

But why at Camden station, to which the troops would have been pulled more than a mile through angry spectators who it already been hurrahing Jefferson Davis. President of the new Confederacy, and cheering president Lincoln for an hour and a half?

Only the day before, a lesser riot (resulting in no deaths) began near the Bolton station one another troop of Pennsylvania Militia (the first defenders) D trained in North Baltimore and was stoned by a mob as it marched south to board a train for Washington. The police applied more and less effective protection for the first defenders while they were of foot in Baltimore on April 18. Why then did marshal Kane apparently reverses strategy on April 19 and decide that the six Massachusetts et al would be safe while on the cars as they were pulled from Pres. Street station to Camden station?

Mayor Brown later decided (in his memoirs of the riot, published in 1887) to the six Massachusetts et al would have been more imposing, therefore safer, if they had marched as a body of 1700 men from one station to the other. Just such an order for marching through Baltimore was apparently prepared by the sixth Massachusetts commander, Col. Edward F Jones, but it was abandoned “someone had plundered” Mayor Brown concluded hinting strongly that some PW and be executives had.

The logic of hindsight suggests that the main body of police should have met the train at Pres. Street station and that adequate details of officers should have escorted each horse-drawn cart of soldiers to Camden station. As it happened the first nine cars of 35 car troop train hauled Col. Jones and seven of his 11 Massachusetts companies of Pres. Street, across Pratt Street and down Howard Street to Camden station with little, if any police escort – and still they made the trip without serious mishap. The crowd hissed but threw stones at only the last car, and Mayor Brown, who by this time had arrived to Camden station from his law office, thought that maybe the nine cars were the lot.

The 10th car was halted at the Pratt Street bridge over Jones falls by a wagon load of sand that the mob dumped in its path, some anchors (perhaps eight that Negro seamen from nearby ships drew across the tracks, and a motley barricade of lumber and paving stones that were handy because the street was by chance under repair at that point.

The 10th car returned to Pres. Street station, where the mob had swelled to about 2000 and where some police arrived (from outlying districts, apparently not from the main body at Camden station) as the 220 or so soldiers D trained and lined up in single file. Their effort to March to Camden station in this unlikely formation was blocked by a knot of men flying the “Succession Flag” so they were formed into double file, about faced, an marched in the opposite direction, (i.e. retreat) conceivably inspired to dive into the harbor and swim West at the Light Street. The mob having savagely choked a union sympathizer, who tried to tear down the “Succession Flag”, circled the soldiers and halted the de facto retreat. The troopers then fell in by platoons, for abreast, and with police help, wedged a path north on President Street. The gang with the “Succession Flag” would march ahead of them and savagely beat two or more union sympathizers who tried to tear down the banner, then ran along the militia ranks. Part of the crowd behind the six Massachusetts columns then began to throw stones, one of which felled a trooper named William patch, who was then beaten with his own musket.

The four companies – C, D, I and L – then began either “to run” or March “at double quick,” presumably one orders from one or all of their captains, who were named Follansbee, Hart, Pickering and Dike. Two more soldiers were knocked down at Pres. and styles streets – possibly by a flatiron or one of the “queer missiles” (meaning chamber pots) that were thrown by Baltimore women in the mob, according to the 1936 reminiscence of Aaron J Fletcher the last survivor of the Civil War six Massachusetts.

Mr. Fletcher is the only direct account that even suggests that any women were involved in the riots. (A romantic story, written in 1865, alleges that a Baltimore prostitute named in Manley saved the six Massachusetts Regiment band by guiding them away from Pres. Street station by back alleys – but most accounts state that the police protected the musicians) at about the time the troops turned the corner into Pratt Street, at any rate, someone fired the first shot.

E. W. Beatty, of Baltimore fired that shot from the crowd, according to the opinion that seemed to be based on the opinions of Confederate officers with whom a he later served before he was killed in action. One of the six Massachusetts soldiers fired that first shot, according to contemporary newspaper accounts that attributed the information to a policeman identified only as “number 71” by that time Mayor Brown had heard that the mob had poured up Pratt Street and had hastened to the bridge. Where he met the new and wonders and joined them in their March at the head of the column as far back toward Camden station as light Street.

Mayor Brown’s account states that he slowed the soldiers pace (they also had to pick their way through the half hazards barricade at the bridge) the Capt. Follansbee said: “We have been attacked without provocations” and that he Mayor Brown replied “you must defend yourselves.”

The troopers of home about 60 carried muskets, then began to fire in earnest – in volleys, according to the newspaper; over their shoulders and helter-skelter, according to Mayor Brown; definitely not in volleys, according to Karen Fletcher’s recollection (although he was with Company E, which passed safely through in one of the nine cars) the first Baltimorean hit (in the groin) was supposed to be Francis X Ward.

A Unionist newspaper in Washington quoted Col. Jones and the next day as saying that Mayor Brown had seized a musket and shot a man during the march. Mr. Brown wrote later that a boy he had handed him a smoking musket which a soldier had dropped and that he had immediately handed it to a policeman.

The Mayor must have found that the Pratt Street riots generally embarrassing. Then 48 years old he had been elected in October, 1860, on the reform ticket dedicated to absolving Baltimore of its nickname “Mobtown” and he helped put down the bank of Maryland riots in 1835. He believed in freeing the slaves gradually, but felt that slavery was allowed by the Constitution and that the South should be allowed to succeed in peace.

He was some early arrested by the federal military in September 1861 and prisons until November 1862 from 1872 until the year before his death 1890 he served as chief judge of the supreme bench of Baltimore city. He was defeated in a campaign for mayor in 1885.

When Mayor Brown left the Massachusetts infantrymen, near Pratt and light Street, most of the casualties had fallen, the fighting having been heaviest near South Street. The Baltimore dead and wounded were mostly bystanders, according to most Baltimore accounts, because the running soldiers allegedly fired to the front and sides and not at the hostile mob behind them which may have been as small as 250 men, according to the “Tercentenary History of Maryland”

A historian who took notable exception to the bystander only version was J Thomas Clark, author of the “Chronicles of Baltimore” which describes an “amends concourse of people” that to a man threw paving stones at the troopers from in front of them.

Before the column reached Charles Street, marshal Kane and about 40 police finally arrived from Camden station and through a cordon around the soldiers. “Halt men or I’ll shoot!” The Marshall is supposed to have cried as he and his men brandished revolvers. The mob halted.

That even marshal Kane telegraphed friends to recruit Virginia rifleman to defend Baltimore further from invasion by union militia. In June, after general Benjamin Butler “occupied” Baltimore with other Massachusetts troops, the police Marshall was also arrested and imprisoned. Released in 1862, he went to Richmond apparently by informal agreement, and apparently served in the Confederacy during the war. He died at the age of 58 and 1878, seven months after he was elected Baltimore’s Mayor.

The six Massachusetts had left Baltimore by 1 PM on April 19, 1861 – short of its dead and some of its wounded, who were cared for in Baltimore hospitals and temporarily buried and Greenmount Cemetery and its regimental bands men who along with 1000 unarmed Pennsylvania volunteers were more effectively protected by the police from two attacks at Pres. Street station by mobs which may have increased to 10,000 persons according to Mr. Scarf’s Chronicle.

The Pratt Street riots occurred on the anniversary of the revolutionary war battle of Lexington, a coincidence which both northern and southern propagandists made a lot of, notably the former the civic leaders of Baltimore called halfheartedly for law and order in speeches in Monument Square when the same afternoon, ordered railroad bridges burned North the city and persuaded Pres. Lincoln to route further worsened the defenders through Annapolis.

Much of the city might protest that its sovereignty had been violated, the riots appeared to the North to be a pro-Confederate outrage, and it is not difficult to understand why the federal government soon decided to clamp down on the city.

The six Massachusetts was in Baltimore three more times during the war. It survivors were felt it here on several occasions afterwards. Its reception on April 19, 1861 caused far-reaching repercussions, though including the ironic turnabout in Baltimore which saw Unionist mobs roughing up success in this one the streets as soon after the riots as May 1861.

Note; Marshal George P Kane was Baltimore’s police Commissioner at the time called Marshal – Mayor George W Brown was the city’s mayor at the time

A map shows the route followed by the Massachusetts infantrymen on their march from Pres. Street station to Camden station

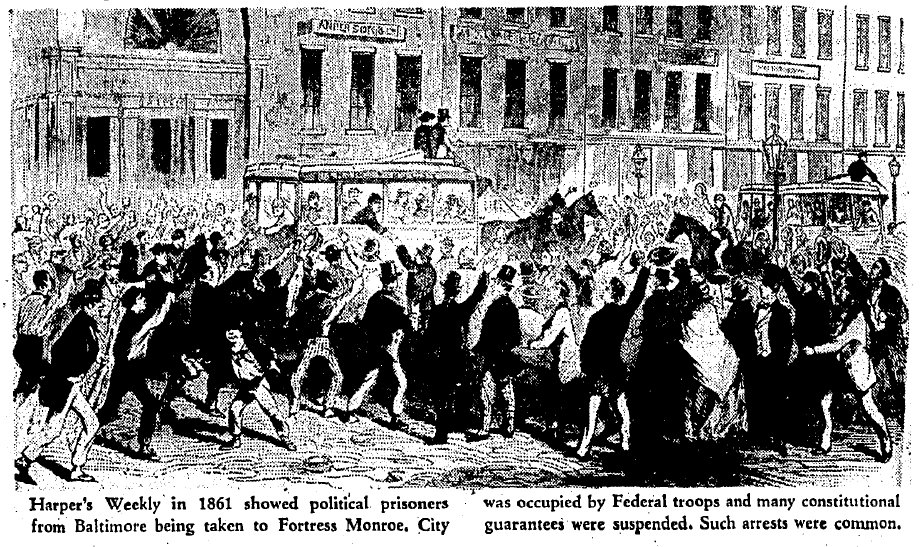

The three contemporary drawings produced above show the six Massachusetts fighting its way along Pratt Street against the mob of April 19, 1861. The middle sketch is from Harper’s weekly the other two are from Frank Leslie’s pictorial history of the war.

The attack on the six Massachusetts was drawn by Albert Faulk Baltimore artist perhaps a witness

Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll