Police Academy

Baltimore Police Academy

School of education

Service with Hope of Honor as Reward

13 Feb 1921

Students write Crime Stories at City Policeman set School

Embryo Bluecoats invent Mock Thrillers as Part of Feral Training Before They Are Allowed to Enter Active Service.

They used to take a man who had “voted right,” place a cap and badge on him, poke a stick in his hand, and say, “Go on out and be a policeman!” Now, right here in Baltimore, they make him write several short story plots, and that is not all.

The cradle of law enforcement in Baltimore is now in a classroom at the Northern Police Station. Chairs are arranged in rows, as in an ordinary law school lecture room. Standing at a large desk facing the rows of broad-shouldered men ranging in age from 21 to 35, is Round Sergeant Albert J. Plantholt, a plain-clothed policeman brimming with ideas and able to speak quickly. Among the things that make it look different from an ordinary law school lecture room are a lot of flying rings hung from the ceiling, weights against the wall, a punching bag platform, and charts showing men being saved from drowning, bleeding to death, and burning up: a red fire alarm box and a green police call box.

Day of Amateur has Passed

This is Baltimore’s Police School, an institution designed to create a metropolitan force of professional policemen. As Round Sergeant Plantholt says, “Baltimore has had enough of the amateur policemen.” He was one himself when he started. When they dressed him up in the policeman’s uniform close to 20 years ago, he knew no more about policemanship than he knew about an airship: he not only admits that but is slightly proud of it in as much as he finds himself today teaching other policemen how to do a scientific job.

Yesterday he talked to a reporter, explaining in detail for the first time how the new scientific policemanship is being taught in Baltimore.

Presumably a mental and physical examination is required for admission to the school, but only the physical examination is really given. It is believed impossible to establish a mental standard for the right to study policemanship beyond the ability to read, write, and understand English. The physical examination, while not too rigid now, owing to a scarcity of men, is adequate.

Three weeks. No man can finish it in less time than that. If by that time his work hasn’t satisfied Sergeant Plantholt, he stays in a school until it does. One man recently stayed there seven weeks.

Curriculum Practical

At first glance, the list of things they need to learn appears to be a simplified version of a university curriculum. Upon closer examination, it is clear that practical policemanship is the general theme of all the subjects, which included “methods and practices of thieves and pickpockets,” “what constitutes evidence and how to present it in court,” “how to find evidence,” “how to catch and subdue criminals,” “how to write reports,” and a score of other things.

Sergeant Plantholt has had to pioneer in building up the school, learning what studies to require and what lessons to prepare as he went along. For instance, one of his recent classes had a terrible time with his spelling. Its sample reports were full of the most atrociously spelled words he had ever seen. In a spelling test he gave them early in the session, the man with the highest average got three words right out of 30.

Sargent Plantholt could not write an essay to teach them how to spell every word in the dictionary, but he did prepare a list of “police words,” or words that reoccure often in a policeman’s literary efforts. A small portion of this list would be included:

Explosion, discovered, sidewall, complexion, grease, amputated, crossed, suspicion, underwear, rape, buffet, pocketbook, Jimmy, stole, identification, description.

Day after day, he had them spell these words, orally and in writing. When that class graduated after three weeks, the man with the lowest average in spelling had scored 89%.

Write Crime Stories

In a sense, they really have to write “short story plots.” In the course of learning what constitutes evidence and how to present it, the student policeman is required to prepare in writing fictitious cases involving the preparation of crimes and the capture of suspects. They imagine every conceivable crime, from the stealing of clothes to the dynamiting of the Custom House, and submit their brief plots to Sergeant Plantholt. With the plots before him, he requires his students to get on an improvised witness stand and rehearse the evidence in the case they have conceived. He marks them for the completeness of detail, accuracy, and ability with which they present the evidence.

They learn about the methods and tricks of criminals from Sergeant Plantholt and William J. Lutts, assistant instructors, who tell their own experiences and relate tales of good policemanship that had become classics in the Baltimore Police Department. However, the most effective method for identifying and apprehending criminals is to learn from their own experiences. The instructors can show them how other policemen have done it, but nothing that any other policeman has done will serve in a brand-new case suddenly flashed before a new policeman. His only resources are his own instincts.

Good Ones Born, Not Made

“Good policemen—by which I mean, “Men who can do the right thing at the right time—are born, not made.” Said Sargent Plantholt, and the way he finds the good ones now at the school is something like this:

Sergeant Lutts goes into a room adjoining the classroom. He pretends he is the victim of a robbery. There is a knock, and he opens the door to admit a student policeman; he will address him as if he were an utter stranger who had been sent for police aid. It is up to the student to get information out of Sergeant Lutts by asking him questions. The sergeant will volunteer nothing.

The big test is whether the student is good enough to look around for evidence on his own account. Sometimes Sergeant Lutts drops a card, a button, or a cigar butt on the floor or fixes up a little trail of red ink leading to a window. If the near policemen discover these things by himself, he is considered a promising fella. If he doesn't discover these things on his own, it's likely that he will continue to work as a police officer for years, reaping no benefits beyond falling arches.

“This school can do wonders,” says Sargent Plantholt, “but there are three things it will never teach and never can. They are a power of observation, ability to get information, and memory for faces. We can awaken dormant instincts for those things, but we cannot teach them. Men are born with them, and whenever we get such men, we grow just a little prouder of this school.

May Study Safe-Cracking

“Pretty soon we may have a safe up in here in the classroom. Then we will give lessons in handling safe cracking cases. We will have the students looking for Sergeant Lutts and my fingerprints, or we would just turn them loose on the safe and see if it occurs to them to look for fingerprints.”

A Day in The Police School is Something Like This

8:30 am – Military drill on the street for an hour, under instructions of Patrolman Lucien Totato, a former lieutenant in the army.

930 to 10:00 am – Calisthenics or instruction in first aid.

Recess of 50 minutes

10:15 am – Traffic laws read, explained, and demonstrated on a model street intersection of wood with toy automobiles and horse-drawn vehicles.

11:15 am – automobile laws studied.

Dinner

1:00 pm – Afternoon session devoted to moot court proceedings with practice in giving testimony, study of the Book of Rules, practice in making reports, lectures on handling fires, thieves, pickpockets, murderers, and so on.

5:00 pm – Adjournment at

During the three weeks, Sergeant Plantholt gives his class 16 examinations in different subjects. He has had 55 students now.

![]()

The following is a series of articles telling how a Baltimorean becomes a policeman.

20 September 1937

By Lee McCardell......... 20 September 1937

1. Policeman For His $40 A Week Must Prove His Knowledge For The Job

He Applies, Takes A Test, And If Passing, Is Put On Eligibility List-Then He Waits Before He Dons A City Officer's Uniform

The policeman-you know him. Where does he come from? And how?

The following is the first of a series of five telling how a Baltimorean becomes a policeman

The policeman toots a whistle, holds up a white gloved hand… helps a blind man across the street….. tries the store doors along his beat after dark…investigates strange noises… and gets $40 a week after two years' probation.

You greet him warmly as "Officer" when at your request, he appears in the middle of the night to discourage someone from jimmying the dining-room window (The person jimmying the window may call him a “bull.") You speak of him as a "cop" when he sticks a parking ticket under your windshield wiper. He's a "flatfoot" if the judge fines you.

Well, you needn't turn up your nose at the next Baltimore policeman you see, regardless of what you call him. He belongs to a select circle of exactly 1,897 Police Department employees.

Breaking into the police force these days is almost as hard as breaking into a bank. The number of department employees, while not the maximum permitted under State law is the maximum for which salaries are provided in the Baltimore city budget.

Should you yourself aspire to perform brass-buttoned constabulary duty in Baltimore, you must wait until a death, resignation or dismissal that reduces the number of names on the Police Department pay roll. Then-- One at a time! Don't rush, There will be plenty of time and plenty of notice First, you must get on the eligible list. From Eligibility List Comes the Appointments

The eligible list is prepared by a board of three police examiners appointed like the Police Commissioner, by the Governor. It is the duty of the board to hold competitive examinations from time to time in order to keep a list of eligible candidates on hand for appointment as probation officers. From the list the Police Commissioner makes the actual appointment.

The present list contains enough names to fill all vacancies likely to occur until next April 24, when it expires. Early in January the board will a advertise an examination to prepare a new list.

To take this examination an applicant must be a registered voter of the State of Maryland. not less than 25 or more than 37 years of age on the following April Fool's Day: not less than five feet ten inches tall in his stocking feet and at least 150 pounds in weight. No color line is drawn.3,500 Are Interviewed In 3-Week Period

Numbered application blanks are handed out in the offices of the Board of Police Examiners, Room 506, on the fifth floor of the police building at Fayette street and the Fallsway. Every day for three weeks, between the hours of 11 A.M. and 1 P. M., the three-board members are on hand to interview applicants. Dr. Dwight H. Mohr, chief physician of the Police. Department, is there to give preliminary physical examinations.

As many as 3,500 applicants have been interviewed during that three week period. Who are they?

Stationary engineers, automobile salesmen, freight truckers, cab drivers, refrigerator service men, manufacturers' agents," professional baseball players, telegraph operators, pipe fitters, tailors, barbers, teachers, clerks, motormen, ice wagon drivers, filing station operators, bookkeepers, auditors, printers, machinists, weighers, markers, inspectors, managers, runners, Painters, elevator operators, steel workers, firemen, butchers, carpenters, paper hangers. bench hands, helpers. laborers. . .Some are college graduates. Step On Scales; Show Your Hands, Applicants

Interests equally as varied are represented by the three examiners who interview these men. W. Lawrence Wicks, president of the board, is the son of a former Baltimore police sergeant and manages a Liberty Heights bowling alley. Sigmund Stephan, the second member, is a retired postal inspector. The third member, Arthur Kadden, is the proprietor of an East Baltimore street hat store. Just inside 'the examining board's office door the men who want to be come policemen step on a scale set at 150 pounds. They have to tip that to get any further. Then they stand beneath a measuring rod fixed to a door frame and set at the required 5 feet 10 inches. Do they wear glasses? Down they go to the office at the end of the hall for an eye test by Dr. Mohr.

"Let's see your hands. Got all your fingers?" A Felony Against You And You're Counted Out

No use going any further if you haven't got the fingers to handle a pistol properly. "Ever been 'arrested? What for?... A felony disqualifies you.

But, passing these preliminaries, an applicant receives a numbered blank with a perforated tab. The tab must be filled out then and there with the applicant's name, address, election ward and precinct. On the back of this tab he is "finger-printed by a police expert assigned to special duty in the examiner's office. This tab with, its finger prints is torn off and retained by the examiners. He Has Questions, Then Some More Questions

The would-be policeman takes the rest of the blank and a sheet of mimeo-graphed instructions home with him.

There he fills out his formal application, writing in the answers to a long list of questions that give his complete personal history, and appending the names of five acquaintances preferably lawyers, doctors, clergymen. willing to vouch for his "ability, industry, character, habits and general fitness for appointment to the Police department of Baltimore city."

He must swear to the truth of all the information he gives about himself. There is a place on the back of the blank for a justice or notary to take his oath. And the completed application blank must be returned to the Board of Examiners by a specified date.

The applicant's' instruction sheet informs him that the examination will be held in the Maryland Institute building at Baltimore street and Market Place on such-and-such a date; that card. of admittance will be mailed to his address a week prior to the examination, and that he will be tested in spelling, arithmetic, locations, and common sense.

Comes Test Time And Room Is Filled

The board makes out its own examinations. Mr. Stephan say, gets up a list of ten good words for the spelling test, Mr. Kadden works up five arithmetic problems. The president of the board figures out ten questions on locations and ten common sense questions. Meanwhile the applicant's age, address, ward and precinct, as they appear on his finger-print tab are being checked against records of the Board of Election Supervisors. Provided there is no discrepancy, he is mailed a card of admittance to the examination. Underscored on the card is the hour when "doors will close." Stamped upon it in red ink is the instruction to "bring your own pencil."

A large class of applicants fills practically all the rooms of the institute building. Each room is supervised by several watchers, Smoking and talking are taboo. Each applicant receives a numbered examination paper for his spelling test and a numbered booklet for the rest of his, written work. Try A Question Or So If You'd Like A Job

An hour and thirty minutes is permitted for the examination after the ten words of the spelling test have been pronounced. When he has done the best he can by his spelling, the applicant opens his numbered booklet and goes to work on location, common sense and arithmetic.

Where, he is asked, are such places as:

(1) The Robert Garrett Hospital for Children?

(2) The House of the Good Shepherd for Colored Girls?

(3) Headquarters of the Maryland Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to

Animals?

(4) The Federal Land Bank

(5) The Armistead Monument?

(6) The Maryland and Pennsylvania Railroad Station?

(7) The Baltimore headquarters of the .Salvation Army?

(8) The Baltimore Cemetery?

(9) The Baltimore Mail Line dock?

(10) What license plates are required on Mail trucks?

(11) In criminal cases, upon whom does the burden of proof lay?

(12) what are the general duties of a coroner?

(13) Where must trials for violation of criminal law take place?

(14) What are three methods by which you might summons Fire Department

apparatus? Easy? Okay, Try Some ! More And Arithmetic

Name three Baltimore public service corporations. Must you be a taxpayer to serve as a juror? What is the name of the system, used for identifying criminals, by means of certain bodily measurements and marks? For what legal reason may a penitentiary prisoner's term be reduced? How can a man, who has served a term for felony, have his citizenship restored?

Arithmetic comes last. Calculations as well as answers must be set down for problems along this line:

If 12 men can earn $270 in 9 working days, how much can 28 men earn in 5 days? An agent sold 9,873 pounds of sugar at 4 3/8 cents per pound, charged

1 5/8 per cent. commission and $2.90 for other expenses. What were the net proceeds of the sale? A son inherited 920 acres from his father and later sold 138 acres. What per cent of his inheritance remained? What is the cost of 58 5/8 yards of goods at 37 1/4 cents per yard? The firm of A and B has a capital of $12.387. A's investment being he $2,387 less than B's. What is each partner’s investment?

![]()

Cop Who Made A Tough Beat Tender Prepares Rookies To Be Officers

22 September 1937

You'll Find No Circus Stunts Or Movie Equipment In Lieutenant Plantholt's School, For There Beginners Learn "The Works" On Policing

The policeman-you know him. Where does he come? And how?

The following article is the third of a series of five telling how a Baltimorean becomes a policeman.

By Lee McCardell September 22, 1937

Lavishly arrayed with all the generalities and semicolons dear to a legislator’s heart the powers and duties of the police of Baltimore are set forth at great length in Section 744 of the city charter.

The policeman's bible, a little black book of department rules and regulations boils it all down to this:

"It is the duty of policemen, at all times, both and night preserve the peace: detect and prevent crime, arrest offenders, protect the rights of persons and property; guard the public health to enforce all laws and ordnances, the enforcement of which devolves upon the police force, and to obey all orders and rules and regulations of the Police department.

But even this is pretty broad. The laws of Baltimore city specifically direct policemen to arrest everybody from persons who breed mosquitoes to people to people who "tie the month of any calf to prevent its drawing from the cow its natural and accustomed food. Where is a green policeman supposed to start?

He goes to school for eight weeks, to find out. No Circus Stunts In This School

There is nothing fancy about the Baltimore Police School of Instruction on the fifth floor of the Police Building at Fayette street and the Fallsway.

Its students are not trained to perform any circus stunts on horseback or motor cycles. Down at the end of the corridor there’s a big gymnasium for any policeman who wants to use it. But the members of the force are "not even taught to wrestle, box or swim.

They study:

1. The powers and duties of police.

2. Department orders, rules and regulations the keeping of records and the making out of reports.

3. Traffic rules and regulations and the handling of traffic.

4. The laws of the State and the ordinances of the city, the enforcement of which devolve upon the police.

5. Procedure in courts at law and at coroner's inquests and the preparation and giving of testimony.

6. First aid to the injured.

7. Setting-up and gymnasium exercises.

8. The care of revolvers and revolver practice. School's Director Made A Tough Beat Tender

Standing is Class Instructor Lt. Adelbert J. Plantholt

Lieut. Adelbert J. Plantholt, director of the school ever since it was established seventeen years ago, is a powerful. white-haired man who had twenty-one years of hard practical policing to his credit before he began teaching probation officers.

Plantholt joined the force in 1901 as a patrolman in the Northeastern district. He was assigned to a beat so tough that it was only one block wide and two blocks long. When he got through with it, it was so tender that, it was added to another officer's beat.

Promoted to the rank of sergeant, Plantholt was transferred to the Northwestern district, assigned to duty on Pennsylvania avenue, the main stem of Baltimore's Negro section. As a round sergeant he went to the Southwestern district. Then former Commissioner Gaither called him in, made him a lieutenant and told him to take charge of the police school. Since then the lieutenant has started off more than 2,000 rookie policemen. Score Goes Up Yearly And Reaches 99 P. C. Every year when the Board of Police Examiners gives its test to make up an eligible list of lieutenants for promotion to the grade of captain, Lieutenant Plantholt finishes first. Every year his score gets a little higher. Last January when the last examination was held, he made ninety-nine per cent. The good policeman, as Lieutenant Plantholt sees him, has four cardinal virtues. These are first, observation, second, ability to get information, third, patience; and, fourth. perseverance and hard work. The lieutenant gives the probationers a little talk along this line when they first arrive in the police school. He reminds them of his four points as they go along. Rookies Begin Their Day At 8.30 am A typical day in the police school begins at 8.30 A.M. when the lieutenant leads his class of fifteen or twenty probation officers in a half hour of physical exercise. From 9 until 9.30 they have a period of simple, close-order military drill. There is plenty of room for both calisthenics and drill in the big schoolroom, which is practically a hall. Then comes a fifteen-minute recess. Off to one side of the schoolroom is an alcove with benches, chairs and tables. Here the student officers relax, talk, smoke if they want to. The lieutenant enjoys a smoke himself. He prefers a pipe. He has a rack of assorted pipes on his main desk lip in the front corner of the room. Recess Ends And First Aid Instruction Starts At the end of the fifteen-minute recess school takes in again with first-aid instruction-also by Lieutenant Plantholt who teaches everything in the schools curriculum. There are cots, blankets and a small white iron hospital bed at the lower end of the room for demonstrations in first aid. A lecture on some phase of police work follows. For this, the students seat themselves in rows of broad-armed chairs ranged, at one side of the room before a platform on which the lieutenant has a chair and desk with a blackboard behind him. He lectures without notes, encourages questions, draws on his own twenty-one years of practical experience on the street for examples of police work. Class Takes Books And Studies Law A t the conclusion of this lecture the class gets out its books and reads and discusses the police digest of city and state law. That takes them up around noon. From noon until 12:30 their time is their own for lunch. After lunch they study the Police Departments own 150 page book of rules and regulations that get down to the fine points of police conduct and deportment by reminding an officer that he must especially avoid giving cause for gossip or scandal by idly conversing with women in the streets when he is in uniform, whether on his post or not. Soft-Spoken Courtesy Expected Of Officers Furthermore, that policemen should be quiet and soft spoken, and that: When asked a question they shall not answer in a short or abrupt manner, but with all attention and courtesy, at the same time avoiding as much as possible entering into unnecessary conversation. And it probably comes as a disappointment to the cockier probationer to read: ":Members of the force shall not swing or toy with their espantoons, but shall carry them as inconspicuously as possible. They Find There's A Rule For Almost Everything More important, perhaps, than these scraps of etiquette, a policeman learns from his book of rules and regulations just exactly what he is supposed to do in case of fire, riot, accident, drowning, sudden death or other emergency. And how to arrest people, handle prisoners, dispose of stolen property and lost children if he finds any. There is a rule and regulation, it seems, for everything a policeman may have to do. When Lieutenant Plantholt thinks his class has had enough rules and regulations for one dose he changes the subject to automobile law. Then they have another recess and another lecture. The day winds up with class study of a model police report of a murder, suicide, burglary or larceny. Each probationer then writes up a similar report of his own. Lieutenant Corrects And Criticizes Papers These are collected by the lieutenant, corrected and criticized. The student officers also have oral and written Quizzes from time to time. They are not graded on any numerical basis. It's a matter of discretion with the lieutenant as to whether their progress is satisfactory. On easels set up in the schoolroom are permanent displays of permits and badges with which a policeman should be familiar, and of the different types of automobile tags and licenses that he should know. Around the walls hang pistol charts and police photographs of scenes of Baltimore crimes. On the bulletin board are copies of police orders and flyers. Miniature Streets Are There To Study A real police telegraph and signal box, back to back with a real fire alarm box, stands on a revolving pedestal beside the blackboard. On a table behind the blackboard is a layout of miniature streets with toy street car and automobile traffic. And once a week Lieutenant Plantholt takes his class down in the basement for revolver instruction and target practice on the police pistol range. The length of a period devoted to any one subject is variable; inasmuch as the Lieutenant teaches everything himself. It may be thirty minutes. It may be two hours. That's one of the conveniences of having everything under one man. The lieutenant wishes he had more room and some additional equipment--no microscopes. No jujitsu teachers. Nothing like that. "That's all right on the stage," he says. "It looks pretty. "But in practical policing a good mental photograph is worth more than a microscope. In a real fight there are no rules. It's a question of getting in there quick-getting in anyway, just so you get there first." 4. Police School Methods Give Rookie A Chance To Show His Stuff In Jiffy "Field Work" Breaks Him In On Every Phase Of Job, And He's Doing Valuable .Duty Even Before He Gets Uniform The policeman-you know him. Where does he come from? And how? The following article is the fourth of a series of five telling how a Baltimorean becomes a policeman. By Lee McCardeIl September 23, 1937 Probation officers have no home work to do when they leave the Police School of Instruction at 4:30 in the afternoon after a hard day of rules and regulations. But every Wednesday and Saturday night they report to police district station houses for what might academically be termed "field work," In plain clothes and chaperoned by full-fledged experienced officers, they do regular police work then. Sometimes they cover a post with uniformed patrolman, learning the routine tricks of the trade. Sometimes they do special duty with plain-clothes men. This part of a student officer's training is entirely in the hands of the captain commanding the district to which the probationer is assigned when appointed to the force. The captain picks out the job and fixes the hours. Captain Charles A. Kahler, Western district commander, to whom three probationers now attending the police school reports twice a week, recalls that in the old days policemen went on duty abruptly without benefit of any previous instruction whatsoever, either formal or field. Man Didn't Even Have Time To Get Uniform He remembers being notified of his own appointment to the force on April 1, 1901, and of being ordered that same day to report for duty that night at the Northeastern Police Station. He remembers borrowing a helmet, a nightstick and a uniform coat from an older officer whom he knew. That was the custom in those days. A man didn't have time to get a uniform of his own when he was starting out. Self-conscious in his borrowed outfit on the sleeve of the coat were four stripes of black braid indicating twenty years of service by its owner at the new policeman posted a younger brother In front of the Kahler home on Orleans street to watch for a street car. When the car came along, Patrolman Kahler dashed out in such a hurry that he upset a child playing on the sidewalk. He Was Handed A Badge, And Off He Went He reached the police station on the verge of a nervous collapse, fearing he had injured the child he had knocked down and might be subject for arrest himself. He telephoned his home and felt better when he learned that the youngster was all right. But the new officer was still far from being calm. He was handed a badge and a number for his borrowed helmet. He joined a squad of officers, including several other greenhorns, that followed a sergeant out of the police station. At Madison Square they halted. “This is your post” the sergeant told Kahler "Caroline to Central Avenue, Eager to Preston street. I'll come back and see you later. A Nice Short Cut, And What It Led To Left to himself to get along as best he could Kahler did what he had seen other policemen do. He walked the streets of his beat, but by taking a short cut through Madison Square neglected the corner of Caroline and Eager streets. This was the very corner the returning sergeant picked to meet his new officer, figuring that Kahler ought to pass there if he patrolled his post properly. The sergeant waited for two hours-until somebody finally told Kahler that he was waiting. Kahler 's hurried to meet him. The sergeant was pretty hot "You can be taken down before the commissioners (there used to be three) for this, he stormed. "On my first night?" moaned the new policeman. He wasn't taken before the commissioners. He learned to be a good policeman. But that was something an officer taught himself thirty-six years ago. Things Nowadays Are Quite Different Nowadays they do things differently. Assignment to actual duty is not so sudden. The student officer begins as an observer. He is not schooled for any particular post or position. He serves a general apprenticeship, gets a taste of all kinds of policing and an idea of his entire district before he puts on his uniform. That apprenticeship runs concurrently with the probationer's attendance at the police School. He reports at the station house for his semiweekly tour of duty with badge, revolver whistle and call-box key. But he is in civilian clothes. Those assigned to the Western district and the practice here is the same as that generally followed in the other districts--are sent to various posts with different patrolmen, but never with the same officer or to the same post twice. Wednesday night the student officer goes to a post in the residential section. Saturday night it's the business section. Next Wednesday night the, market section. Next Saturday night a Negro section. Every Neighborhood Poses New Problem

He learns the boundaries of the different posts, their streets, courts and alleys, the locations of the red fire alarm boxes and the green police signal and telegraph boxes. He learns to keep an eye on unoccupied buildings, cheap saloons and traffic. Each neighborhood presents different problem to a policeman. On special assignments with experienced plain cloths policemen, he investigates alleged disorderly houses, suspected gambling establishments. In some respects this sort of work is his most important contribution to the police department at the beginning of his career. The old experienced plain-clothes men of the district are often known to persons who make a point of tipping off a suspect whenever they show up. But the new student officers, strangers to the neighborhood, a policeman is never assigned to a post on which he lives-manage to get into places and see things where the experienced man can't. The Sort Of Place Where New Man Shines Perhaps it's a house where gambling is going on. The place may be wide open. But when the old plain-clothes man barges in he merely finds a few people sitting around playing cards. The student officer gets upstairs, before anyone knows who he is and, maybe finds a big league crap game running full blast. Because he is unknown and unsuspected, a student officer can go into a store where pinball machine checks are being redeemed in money contrary to law-and make out a case for an arrest. He can go into a book making establishment and do the same thing. He can drop into a tavern where liquor is being sold illegally on a beer and wine license and buy a pint that I would be refused to a known ·plain clothes policeman. Some Of His Quarry ~ Actually Welcome Him Streetwalkers, plentiful in some neighborhoods but uncannily wary of the ordinary plain-clothes man, flirt with probation officers, without hesitation. The student officers are invited into disorderly houses. Fortune tellers welcome them and tell them the all the things that a regular plain-clothes man can never tempt them to recite. In all these cases, of course, a regular plain-clothes man follows on the heels of the tenderfoot, backing him up immediately once a law violation is uncovered The student officer is sent ahead to prepare the way. He is something of a bait. When he finds what the experienced officer is looking for he gives a signal and the pinch 'is made. Then Come Occasional Assignments Alone After they have begun to learn their way around, student officers occasionally are sent out alone on relatively unimportant assignments. Perhaps a minor traffic situation at some intersection. Or a bunch of boys throwing stones at windows. Innumerable complaints of this sort are being received constantly at the station houses. Saturday night is the big pocketbook snatching night of the week. Many women are on the street marketing for Sunday. The methods by which the pocketbook snatchers operate are explained carefully to the probationers, who are then posted in localities where trouble has occurred or is anticipated. A. week or so ago a student officer, assigned to the Western district and stationed on the. Washington Boulevard to watch for purse snatchers, saw a man go down an alley and break open a window. The officer went after him and caught him-a burglar. Night Duty First, Then Daytime Turns As a rule the student officers report to their station houses at 6 o'clock and work until 11. But sometimes they are called on day duty. The district commander phones Lieutenant Plantholt, at the Police school, asks that a certain student be permitted to leave the class and report early for some special assignment. In the meanwhile instruction continues at the police school with lectures, discussions and demonstrations. At the end of eight weeks the probation officers are given a final examination. Lieutenant Plantholt gives them a last talking to, a bit of fatherly advice along personal and intimate lines. That constitutes their graduation. Men Studied To See Where They Best Fit The captain of each police district studies the probationers assigned to his command, tries to figure out where each man will be most useful. A new officer who formerly did clerical work is probably best suited for duty in a residential section. A former truck driver, harder boiled than the clerk is the better of the two men for work in a lively Negro section. At the same time such a section calls for a man who is calm and cool, and who Isn’t afraid of anything on earth. If a probationer proves himself unusually useful as a plain-clothes man, he may remain on plain-clothes duty for a while, even after he has completed his eight-week course of training. A new officer is rarely assigned to a regular post when he first goes on full time duty. He is more likely to be used as a relief than for any post.

![]()

City Makes Honest Men Of Police Pupils; They're Scrutinized Fore And Aft

21 September 1939

Watchers Pace Aisles During Tests-Candidates’

Finger Prints Are Checked, Then Detectives Take Up Their Trails

The policeman-you know-him. Where does he come from: And how?

The following article is the second of a series of five telling how a Baltimorean becomes a policeman

By Lee McCardell September 21, 1939

If a man has lived in Baltimore long enough to be a registered voter and has the equivalent of a grammar school education the Board of Police Examiners figures that he should be able to pass its written test for probation patrolman without consulting any notes on his cuff.

But human nature being as frail as it is, the tests are not conducted under the honor system. Alert watchers walk up and down the aisles of the Maryland Institute's Market Place building during the hour and a half the examination is in progress. There must be no whispering, no rubber-necking. If anyone taking the examination is caught cheating, his paper is taken up and he is disqualified.

Before an aspirant may leave the building after taking his examination, he must fill out still another blank form stamped with the number of his examination papers. On this last form he writes his full name and address. Another impression of his finger prints goes on the bottom of this sheet. This is to prevent an applicant from sending in some one brighter than he is to take his written test for him. Finger Prints Checked With Applications

The last signature and set of finger prints arc compared with those on the applicant's original application tab before his paper is accepted as genuine. The three examiners then get together around a big desk in their inner office at the Police Building, close the door and go to work.

The examiners are "three sober and discreet persons." according to the law who draw $1,200 each year with $1,800 for a secretary and $900 for office expenses. Appointed for two years examiners are required to have been registered voters for three consecutive years prior to appointment. Two of the examiners must be adherents of the two leading political parties of the State. But there are no educational, qualifications for a police examiner.

Triple ,Check for Prevents Error Grading a batch of probation officer examination papers is a pretty good job, particularly, as each of the three are sober and discreet persons around the desk checks all the answers to all the questions on all the papers. This triple check is to prevent error. The examiners work holidays as well as week days in order to have all the papers the marked in time to prepare a new list the of eligible candidates for the police force by the latter part of April when the old eligible list expires.

Not al the men who apply to the board for application blanks and preliminary physical examination show up to take the written test. Probably half of those who take it pass. The principal stumbling block is the common-sense questions. Sometimes they give even the college graduates trouble.

Applicants Get Chance To Challenge Grades Correct answers to all questions given in the test are posted after the examination on a bulletin board in the examiners' outer office. All examination papers are kept on file, and if an applicant questions the grade he receives he may ask to see his paper. Papers are graded on a basis of 100 per cent. The passing mark varies. Sometimes it is 60 per cent. Sometimes it is 70.

A list of at least a hundred candidates who passed the test, beginning with the names of those who made the highest marks and coming down the line, is now certified by the Board of Examiners and sent downstairs to the office of the Police Commissioner. After That He Picks Whom He Pleases

From this list he may pick anyone he pleases to fill existing vacancies in the ranks of the patrolmen. He is not required to select the candidate with the highest grade first. He can pick‘em out anywhere on the list. And if he want another list, the Board of Examiners must supply it.

Having made a tentative selection for appointment, the commissioner calls in a couple of men from the Detective Department and assigns them to investigate the persons who have indorsed the candidate's original application, and to scout around the candidate's neighborhood and find out just what kind of a fellow he is. Physical Examination Is Next Hurdle

If the candidate survives this test he is called into police headquarters for a complete physical examination by one of the department's half dozen physicians. When pronounced one hundred per cent sound by the doctor, he is appointed a member of the force and assigned to duty in one of the eight districts.

An attaché of the commissioner's office takes the appointee up Fayette street to the Courthouse. In Room·205, the office of Stephen C. Little, clerk of the Superior Court of Baltimore city, the appointee is sworn into the police service with the following oath: "I . . . do swear (or affirm) that I will support the Constitution of the United States, and that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to the State of Maryland and support the Constitution and laws thereof; and that I will to the best of my skill and judgment, diligently, faithfully, without partiality or prejudice, execute the office of probation officer of the police force of the city of Baltimore according to the Constitution and laws of the State." Presto! He's A Policeman

This oath is printed in a gray indexed ledger, the police test book, kept on file at the clerk's office. After taking the oath with up-raised hand, the probationer signs his name in the test book, initials the district to which he has been assigned and sets down the date.

He's a policeman now. But he doesn't know anything about his job. He.

doesn't have any equipment. So back to police headquarters he goes and, takes the elevator to the fifth floor to report to the Police Department's School of Instruction for an eight-week in course in policing. Veteran Of 37 Years Is Teacher

Right next door to the offices of the Board of Police Examiners, the School of Instruction occupies the greater part of the fifth floor in the Police Building's south wing. It is one big room, subdivided by rows of steel lockers. At a large desk just inside the door sits the schoolteacher, Lieut. Adelbert J. Plantholt, a gray-haired police officer of thirty-seven years experience.

Here the probation officer receives his stick (known almost exclusively in Baltimore as an espantoon), pistol, a badge, cap device, whistle and a key to police telephone and signal boxes.

As a rule, this is a second-hand equipment previously used by the officer whose death, resignation or dismissal created the vacancy to which the probation officer has been appointed. Goes About Armed At All Times

Like any other officer, the probationer is supposed to carry his pistol badge, whistle and key with him at all times, in uniform or out, and to arrest violators of the law who come within his jurisdiction. He may not know at first what his jurisdiction is, But Lieutenant Plantholt will put him wise.

To facilitate the increase of his wisdom, the probation officer receives a copy of the rules and regulations of the Police Department, a 500-page digest of state and city laws, a booklet containing the automobile laws another containing the traffic laws and, an American Red Cross book of first aid instruction. BUYS Own Clothes At $100 An Outfit

He attends school every day except Sunday from 8.30 to 4 in his civilian clothes. A week or so after his induction he goes down to a clothing establishment at Baltimore street and Market Place to be measured for his uniforms. But he won't wear a uniform, except for his own delectation, until he has completed his course of instruction and been assigned to regular duty.

At his own expense he is required to buy a dress uniform coat with a double row of brass buttons for spring and fall wear, a uniform blouse with open lapels for summer, a winter overcoat and the necessary trousers. This outfit stands him about $100.Shoes, Neckties And Such Are Extra

Collar ornaments are included with his uniforms. But the black shoes and black neckties required by department regulations are extra. So is a raincoat, or a pair of gloves, or a pair of gum boots, if he wants them. All police uniforms proper, of fixed specifications, are supplied by one firm of clothing manufacturers, chosen by the department on a basis of competitive bids. This firm has a contract with the department, and until his uniforms are paid for deductions of $1 a week are made from the probation officer's pay. They Start At $35, Minus 2%

During his first year, when he is rated as a patrolman, third grade, his pay is $35 a week, less a deduction of two per cent. for the police pension fund. During his second year, when he advances to the rank of patrolman, second grade, he gets $37.50 a week. As a first-class patrolman, after two years of probation, he should draw $40 a week. Pay days come twice a month, on the first and the sixteenth.

The probation officer does not pass through his early training period alone. He is a member of a class in the police school. Probationers are usually appointed in groups of ten or twenty, " possibly half a dozen times a year, depending upon the turnover of the department.

During 1936 only forty-three new patrolmen were appointed to the force.

“It's a good job," says President Wicks, of the Board of Police Examiners. "A policeman seldom wants to give it up."

Insignificant Police Captain-Did the prisoner offer any resistance? Answer-Only one buck, and I wouldn't take it.

![]()

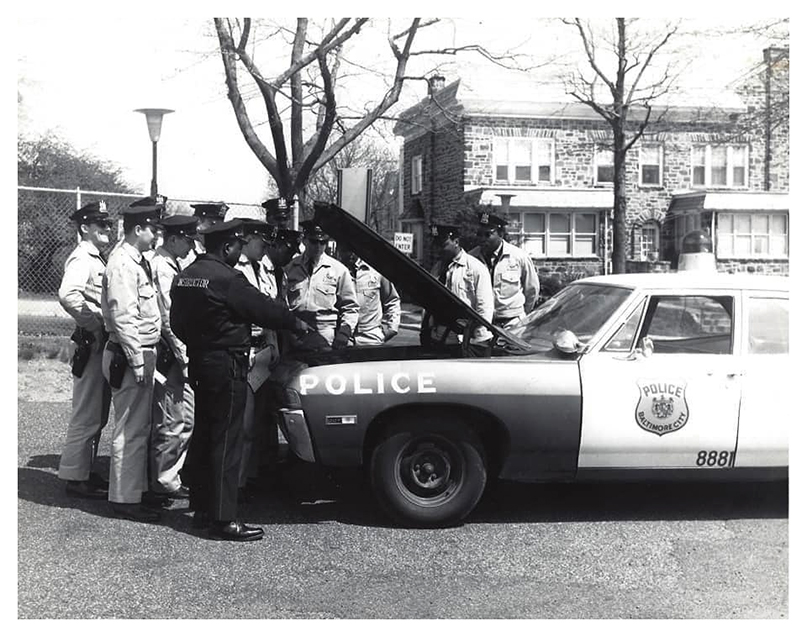

Efren Edwards Sr. showing the recruits the parts of the car,

![]()

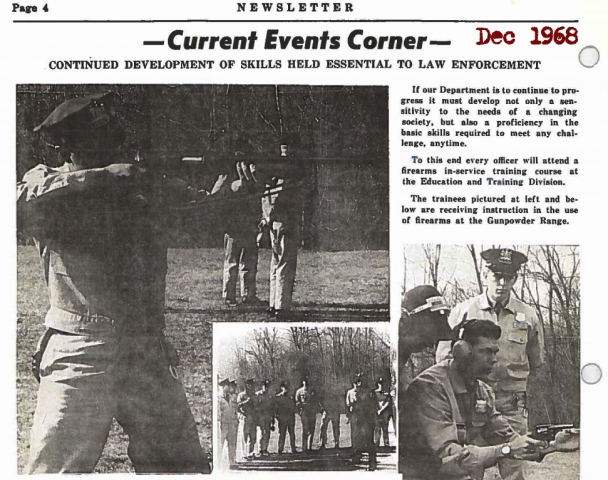

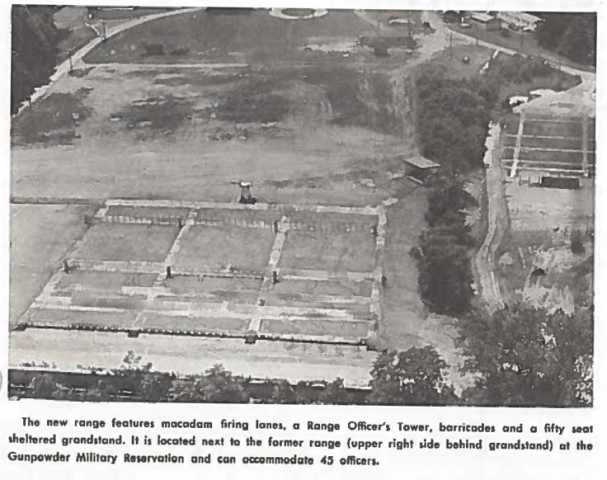

Gunpowder range info

Opening of the Gunpowder Range

BPD Newsletter Dec 1968

Click HERE or the article above

Reopening of the Gunpowder Range

1975 BPD Newsletter click HERE

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to Honor the fine men and women who have served with Honor and Distinction at the Baltimore Police Department.

Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll