Statement Analysis

Statement Analysis

A lie will only hide the truth; it will never replace or become the truth

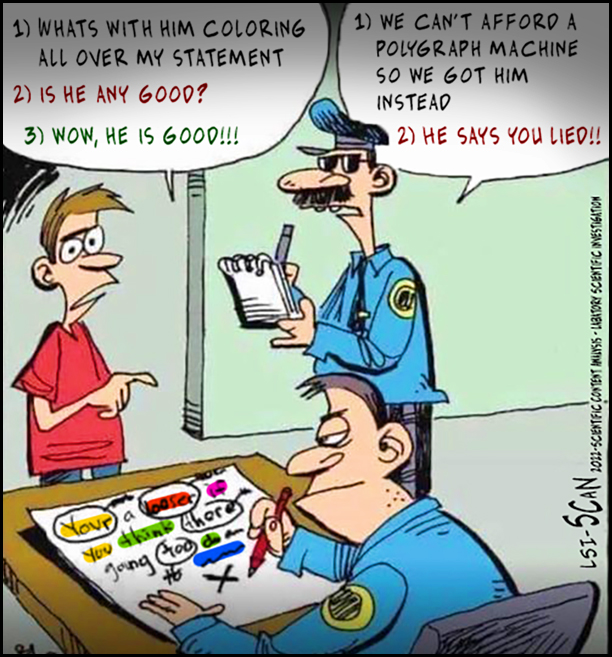

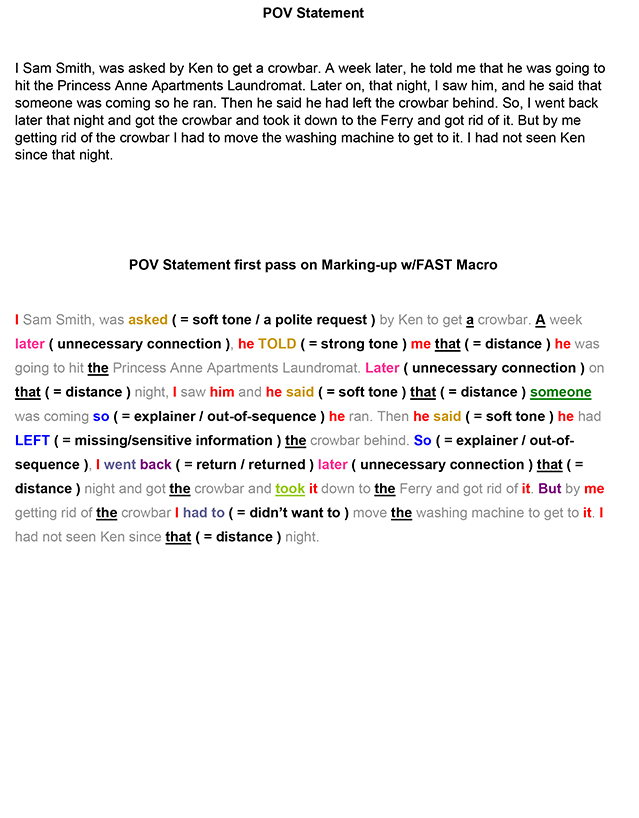

SCAN was developed and refined by Avinoam Sapir and has become one of the most effective techniques available for obtaining information and detecting deception from statements of victims, witnesses or suspects. SCAN (analysis of statements) is an essential tool for law enforcement personnel, investigators, social service personnel, and anyone else who needs to obtain information from written material. Initially, it is best with a written statement, but once one has enough training, and experience they can just as easily do this with spoken words, which can be used in real time during an interview or interrogation. LSI provides SCAN training throughout the US and Canada, and also in Mexico, the UK, Israel, Australia, and other countries. More information can be found at a link on the bottom of this page

SCAN is the original and best technique for analyzing statements. Don't accept any imitation or unauthorized training!

1992: SCAN (Scientific Content Analysis) was brought to the Central District's Major Crime Unit. SCAN was a Linguistic Polygraph technique that, at the time, was so new that the department had never heard of it, and as such, they refused to pay for the course. Officer Driscoll was coming back from a line of duty injury and had received a Workers Compensation payout. Ken used a large portion of that to pay for the training. Within a few months of Driscoll showing, it to different units throughout the department, he was invited to help with various cases, analyzing statements in just about every unit or division within the department, everything from Homicide to Sex offenses to Robbery, Missing persons, and all of the robbery and burglary units in CID and the district's MCU (Major Crime Units) or DDU (District Detective Units). He started out being limited to "Area 1," and before long they added Area 2, but of course if someone came to him from Area 3, he wasn't turning them down. Ken couldn't resist helping out in any and all cases. He also did statements for the State’s Attorney’s Office and various outside agencies like Baltimore County, Ann Arundel County, and Maryland State Police anyone that came to him for help with cases, he took their statement's and trust me, he was loving it. I know he used to come home and tell me and the kids about various cases which taught us how to use the technique. Our youngest daughter was born in 1993, so she grew up learning this technique, while learning to talk, she was learning to detect deception, often while she and her father got to talking, it seemed they both use the technique as if it were second nature to them. I know what it did for Ken's career and am seeing what it is doing for hers. One was a detective, the other a student psychologist. Let's face it, the truth is the truth, and knowing where the truth ends and deceptions begin will help anyone on any career path. Before leaving the department in 2001 for surgery due to a LOD injury, Det. Driscoll was asked to teach his introductory course to Baltimore's Homicide Unit. BTW His course was authorized by Avinoam Sapir from LSI. Avinoam Sapir developed and refined Statement Analysis, and because Det. Driscoll took it so seriously that he found several observations that had not yet been discovered, Avinoam called Ken a Guru on the subject. "Point of Perspective, "Here vs. There" was just one of Kenny's many observations that were eventually included in LSI's training after Ken brought it to Mr. Sapir’s attention.

Ken still uses the technique and practices reading statements, even though he has been retired since 2003. One of the more well-known cases he was involved in was the Laci Peterson case, in which he contacted the Modesto, California, Police and offered his assistance, providing an observation of Scott Peterson's words. These observations came within five days of Laci’s going missing. Based on something Scott said to the media about his wife's disappearance, Kenny knew she was dead and not missing, as Scott was trying to report. To Ken, it came easy: if Scott Peterson knew she was dead when everyone else only suspected her as missing, then he must have killed her. At the time, The Modesto, California, Police said it was too early; they didn’t want to accuse him of anything too soon. But within the year, they asked Ret. Det. Driscoll for a complete write-up of his observations. BTW, I should point out that at first, he wasn't welcomed with open arms; initially they said something to the effect of, "If she is dead, and he knows it, as you said, he isn't the only one, because you also said she is dead, so how do we know you didn't do it?" Ken said, "Well, I am maybe 3000 miles away, give or take, and I am in a wheelchair, so good luck with that theory. When you find out she is dead, I can tell you about when and where she got dead. Feel free to contact me." Kenny was able to tell them what room she was killed in and the approximate time that she was killed, all based on Scott Peterson’s words. Within a year, Laci’s Body was recovered, and Scott Peterson was arrested, tried, and convicted of her murder. Other cases he assisted with included Haleigh Cummings, in which police were told to look more closely at the girlfriend; Ken was told she passed her polygraph. Ken said, "No offense, but the polygraph is only as good as the examiner and the questions asked. I know from the words used; the girlfriend knows more than she is telling." A few years later, it was determined the girl may have been taken from the girlfriend over money she owed for drugs.

The technique is very strong in the right hands and has been used to solve many cases throughout this country and internationally. The first time it was actually used in a case for Baltimore police was about 6 to 8 months after Ken had started using it; he had come back to work after a surgery that nearly ended his career in 1993. He had been telling everyone about the course and how it worked. One night a call came out for a carjacking, and within 45 minutes of the report, some officers in Sector 4 of the Central District found the car with a driver that matched the description given in the BOLO. The officers thought it would be an easy case for Ken, and at the same time, he could get them a quick confession, making the court part easy for everyone. Ken sat down and had the suspect write a statement. Ken began to read and analyze the statement. After the first read over, he found nothing, so he read it again and again, but he couldn't find the deception. Confused for a few minutes, he began to doubt his ability with a technique that during training he never had trouble with; he was 100% in training statements. Then it hit him: during training he never had a truthful statement, so he called the reporting person in, and in order to get what is called a pure original statement, he explained he was just handed the case and knows nothing at all about it, so if he could, would he write down what happened? This was important because if you ask someone to tell you what happened and they tell you, then ask them to write it down, the words in the written statement will be different from the spoken statement, and those changes could be important. So, Ken always had it written before they talked. Not that if they weren't there, there wouldn't be other words to use, but the life of an analyst is much easier if everything is pure. As the victim of this carjacking finished his statement and started to turn it 180 degrees from his seat to Ken's across the table from him, Ken had glanced down and already seen deception on the page. Even more was found when he read the entire statement. After being confronted by Ken and before leaving, the reporting person gave a new statement, one with no deception, that nearly matched word for word with the statement given by the suspect arrested in that car. This was important as it cleared a man of false charges made against him—charges that could have kept him locked up for anywhere from 6 months to a year before a trial may have set him free, and even then, it would have been up to the reporting person to have come clean. Ken letting the carjack suspect go didn't go off without a hitch; the arresting officer and his sergeant wanted Ken's butt. But once they learned, Ken didn't just let a guy go because the guy fooled him or refused to confess; he had the reporting person confess, and better yet, without knowing what the arrested man said, the reporting person gave a similar version of events. So, this started off big, and when the Major learned of this newfound technique, it led to Ken's being transferred to the major crimes unit, where he would work the last 10 years of his career and receive 4 of his 6 Officer of the Year Awards. Now, after being retired for 15 years, Ken received the 7th Officer of the Year Award, which was written more like a lifetime achievement award and can be found on another page I made for him that you can find by clicking HERE.

![]()

"It does not take many words to tell the truth." Sitting Bull

"Just as it takes few words to tell the truth, it often takes many words to bury a lie.."

When we speak the truth, it is concise and straightforward, requiring no embellishments or elaborate explanations. On the other hand, when someone tries to conceal the truth or deceive others, they often resort to lengthy explanations and convoluted stories to cover up their lies. This highlights the power and simplicity of truth, as opposed to the complexity and verbosity of falsehoods.![]()

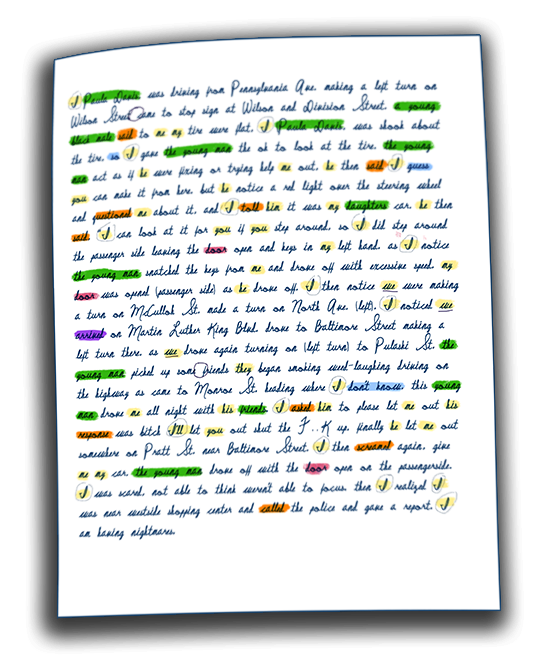

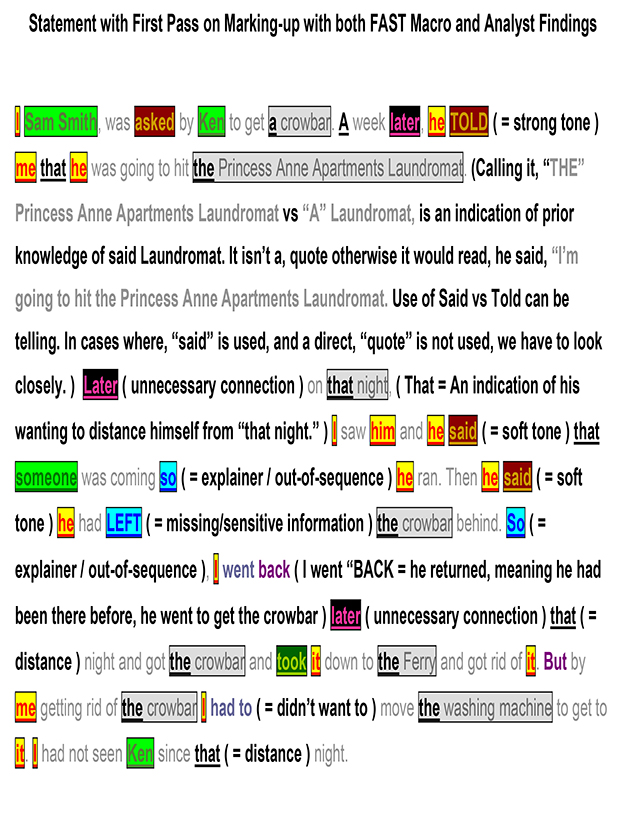

In 1993 the following statement was written by a citizen who had earlier in the night reported he was the victim of a carjacking. This statement was not written until after he filed his report with Southern District Patrol and a suspect was arrested within 45 minutes by Central District Officers while he was still in the car. The suspect in that arrest gave a statement, to a Central District Patrolman that had studied and learned a new technique that provided a kind of linguistic polygraph. It is interesting that after a year of trying to get this technique seriously looked at by the department, it took this case to change things.

Using the SCAN technique, the officer found the statement provided by the suspect in this case to have been credible. With this the officer called the reporting person into the district to tell him he had taken over his case, and that he wanted him to write a statement as to what happened, while the officer pulled reports. Within 15 minutes of reading the statement, the officer had a confession from the victim, stating that he had lied, and that he was not carjacked. He gave an account of the night’s events that matched more closely those given by the suspect they had in holding. As promised the guy they had in lock-up was released without charges. Making the first time this technique was used, in our agency, it was used to clear an innocent man from being charged with a very serious crime. The Officer was transferred to the District’s Major Crime Unit where he remained for the next 10 years, clearing the innocent, and gaining confessions from the guilty. He also trained and will still train any Baltimore City Officer interested in learning the technique for FREE.

![]()

Voice stress analysis (VSA) and computer voice stress analysis (CVSA) are collectively a pseudoscientific technology that aims to infer deception from stress measured in the voice. The CVSA records the human voice using a microphone, and the technology is based on the tenet that the non-verbal, low-frequency content of the voice conveys information about the physiological and psychological state of the speaker. Typically utilized in investigative settings, the technology aims to differentiate between stressed and non-stressed outputs in response to stimuli (e.g., questions posed), with high stress seen as an indication of deception.

The use of voice stress analysis (VSA) for the detection of deception is controversial. Discussions about the application of VSA have focused on whether this technology can indeed reliably detect stress, and, if so, whether deception can be inferred from this stress. Critics have argued that—even if stress could reliably be measured from the voice—this would be highly similar to measuring stress with the polygraph, for example, and that all critiques centered on polygraph testing apply to VSA as well. A 2002 review of the state of the art conducted for the United States Department of Justice found several technical challenges to the technology, including the same problem of determining deception. When reviewing the literature on the effectiveness of VSA in 2003, the National Research Council concluded, “Overall, this research and the few controlled tests conducted over the past decade offer little or no scientific basis for the use of the computer voice stress analyzer or similar voice measurement instruments”.:168 A 2013 paper published in Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics reviewed the "scientific implausibility" of its principles and "ungrounded claims of the aggressive propaganda from sellers of voice stress analysis gadgets".

Confession made following a voice stress examination was allowed to be used as evidence in a case in Wisconsin in 2014. In the case of the murder of 12-year-old Stephanie Crowe confessions were made while three suspects were undergoing VSA which were later found to be false by a judge; the manufacturer of the VSA equipment later settled a lawsuit that alleged that it was liable for the harm the three suspects suffered. In a similar case, Donovan Allen falsely confessed to killing his mother after failing a VSA test. He was acquitted 15 years later based on exonerating DNA evidence. George Zimmerman was given a VSA after he fatally shot Florida teenager Trayvon Martin in 2012.

![]() False Confessions

False Confessions

To see full size article click HERE of on article above

One thing the Major Crime Unit didn't deal with much, were false confessions. One time they had a guy claim he gave Ken a false confession, even provided a polygraph result that said he had passed the test, clearing him of the theft being investigated. This was done in an attempt to clear himself. Ken suggested he do one of two things: either allow the department's polygraph examiner to retest him or have his polygraph examiner retest him using Ken's questions. Ken said a polygraph is only as good as the questions and the examiner. He emphasized that it was crucial to ensure the accuracy of the polygraph results by using standardized and unbiased questioning techniques. Ken also highlighted the importance of having a qualified and experienced polygraph examiner who follows strict protocols to minimize the chances of a false positive or an incorrect negative finding. In this case, the suspect said he would still go to trial and plead guilty, but he just wanted Ken to know and believe that he didn't do it. Ken told him that if he didn't do it, he couldn't take a guilty plea because the courts wouldn't knowingly allow it. Ken stuck to his guns, saying he either needed the questions asked or to have him retake the test using Ken's questions. Ken explained that, not knowing the questions, he could have had someone quiz him on a totally different crime than the one being investigated. In the end, the guy agreed that that was what he had done; he had written out the questions for his polygraph examiner in a way that he could easily answer them as if he didn't commit the crime being committed because he was being questioned over a different theft. He said he knew if he had to answer any questions written out by Ken, they would have been more specific to the crime he had committed, and he wouldn't have been able to fool the system.

It should also be noted that Ken didn't know the questions he was asked. Ken was handed a letter saying he passed the polygraph and was cleared of the theft being investigated. But there were no examples of the questions. For all Ken knew, the questions could have been, "Did you steal the Mona Lisa?" "Did you steal the Hope diamond?" to which the suspect could honestly answer, "No, he didn't!"

When confronted, the suspect went on to say that when he confessed he was being honest, he did rob his company's safe and steal the daily receipts. His girlfriend had broken up with him when she learned he had stolen from his workplace. He tried to claim he had provided a false confession. And he came up with the idea of writing out questions about a different theft than the one being investigated; he found a theft in the newspaper, so it would be current, and he could convince the polygraph examiner to think it was the crime he was being charged with or suspected of. In the end, the polygraph technician cleared him of that crime, but Ken had never suspected him of committing that crime in the first place. Ken said that, to be honest, it might have worked. Ken was busy, overworked, and had more important cases on his desk when the guy came back in. But like most cases, when Ken was heavy into SCAN, a single word or phrase stood out; it just stuck with Ken, and here, the note said it, and the suspect said it, and what Ken said felt like too much emphasis when the suspect said, "I passed the test, proving I didn't commit the theft being investigated!" The way he said, "The theft being investigated!" which was also written on the letter that said he passed the polygraph. It just drew too much attention to the fact that there may have been another theft other than the one being investigated, and when it seemed too many words were used or words were uncomforatably strung together, it stood out to Ken, making him question why.

Ken always felt that if you ask the right questions and the suspect confesses and provides information that could only be known by the person that committed the crime, a false confession is less likely and more impossible. He cautioned against giving information during the interview. There was a saying his instructors said, "Be the well, not the fountain." Meaning, gather information, don't give it out, and be careful with your questions, because your questions can teach the interviewee what not to say as he or she learns more about what you know or don't know about the crime being investigated. In the end, he confessed for a second time that he did rob the company safe. All the company wanted was for him to find a new job.

NOTE: Technically, he could have taken an "Alford Plea." Almost 50 years ago, the US Supreme Court recognized that if certain criteria were met, a sentencing judge could accept a plea—in effect, a de facto plea of guilty—from an individual who maintained they were, in fact, innocent. In the case, Alford pleaded guilty to second degree murder in order to escape a potential death sentence. Ordinarily, a guilty plea must include a knowing and intelligent waiver of trial and an admission of guilt. In fact, a trial judge must generally conduct a searching inquiry into whether or not there is a factual basis that a crime occurred, that the defendant committed it, and that this is the conduct to which the defendant is admitting. As a detective, Ken used the same standards; he wouldn't take a confession on a crime he didn't think the subject committed. In Alford, the Supreme Court determined that an admission of guilt was not constitutionally required. Ken knew of Alford pleas but wanted a case that was unquestionably a case of not just knowing he had the right guy but also making sure that guy knew he wasn't fooling anyone. Well, may his girlfriend. Ken wasn't their couples counselor, and often when he broke someone for falsely claiming they were abducted, it was reported as a kind of a late note to explain to a wife, husband, mother, etc. why they were not somewhere they should have been. Once broken, Ken used to tell them, "You can lie to your wife, your mother, or your preist, but don't lie to the Baltimore Police!" Ken took pride in his ability to not only uncover the truth but to also instill a sense of accountability in those he interrogated. His stern warning served as a reminder that honesty is crucial when dealing with law enforcement. Ken's dedication to his job earned him the respect of his colleagues and reinforced the importance of trust and integrity within the community.

![]()

It was a long time after the Polygraph that two new techniques came along,

Polygraph Machine and Voice Stress Analysis

![]()

POLICE INFORMATION

If you have copies of: your Baltimore Police Department Class Photo, Pictures of our Officers, Vehicles, Equipment, Newspaper Articles relating to our department and or officers, Old Departmental Newsletters, Lookouts, Wanted Posters, and or Brochures. Information on Deceased Officers and anything that may help Preserve the History and Proud Traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to Honor the fine men and women who have served with Honor and Distinction at the Baltimore Police Department. Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll