Row Homes

The History of our Baltimore Row-Homes

Updated on January 13, 2017

This is an unofficial page, we are trying to get permission from the author and if not given soon this page will be removed.. we are thankful for the information gathered, and wanted to share it. But it is important to give credit where credit is due and let people know we did not write this it was brought to our attention by another reader of this page who thought we would be interested as he knows just how much we love the City of Baltimore

Look at the varied facades, the arched window embellishments, and balconies. | Source

Baltimore has more rowhouses than any other city in the United States. The long rows of brick catch the sun and seem to glow with that warmth we associate with home. Basement windows hold little dioramas with personal or religious themes, and painted screens turn narrow streets into outdoor art galleries.

A row house is much more than a line of attached homes. Before the advent of real estate speculation and planned developments, many homes were attached, forming rows. But a real rowhouse describes a large group of similar homes built at the same time by the same builder. The early 1900s saw large developments of these homes when builders created entire new neighborhoods.

The proliferation of these dwelling made Baltimore a city of homeowners. In the late 19th century, 70% of the population of the city-owned their own homes. Practical, cozy, and attractive, these old homes are fuel-efficient.

When I was a girl growing up in the late 1950s, my auntie's row house still had a coal bin and a basement kitchen that was warm in the winter and cool in the summer. The large end group house had a corner store in its high basement. Step over the marble lintel and into a small shop where the owner knows the names of all his costumers, and the favorite ice cream flavors of the children.

Listen to the twitter of sparrows and the call of the grabber, the fruit seller with his horse and cart clattering up the alley, bells tinkling, the soft chatter of neighbors out on their stoops, the laughter of children as they run up the alley. You're in Bawlmer, hon!

Painted Screens

Painted screens helped homeowners to see out while passersby couldn't see in. | Source

In the summer of 1913, the corner grocer at Collington and Ashland Avenues in the heart of Northeast Baltimore's Bohemian (Czech) community, was the first person to introduce colorful scenes on the woven wire. William Oktavec painted the front doors of his shop with images of the meat and produce he sold inside.

A neighbor admired his artwork and its practical bonus of preventing passersby from seeing inside his store, while she could see outside. Wishing to maintain privacy in her rowhouse, she asked Oktavec to paint a screen for her front window and presented him with a colorful scene from a calendar. Each of her neighbors demanded their own - for every window and door of the house. Adjacent communities, in turn, had at least one enterprising painter eager to imitate the new trend, accommodate clamoring residents, and make some easy cash.Artists and dabblers have continued the tradition ever since.

In 1922, Oktavec opened The Art Shop at 2409 East Monument Street where he sold painted screens by the thousands and taught art classes to neighbors of all ages. This was in addition to his church restoration and retail framing and art supply businesses. One of his students, Johnny Eck assisted three generations of Oktavecs when business was especially brisk. In the heyday of painted screens in the 1940s and 50s, resourceful men and women plied the streets of Baltimore by foot, by car, and from modest storefronts, supplying as many as 100,000 screens to eager homeowners. Over the years the popularity of painted screens ebbed and flowed. First, the World Wars dealt a blow, then air conditioners, then changing demographics and changing definitions of modernity. Today, renovation, replacement windows and the rising costs of custom art work add to the toll. At the same time, a revolution in crafting and entrepreneurship has found an eager audience of artists and admirers to take the art form into the 21st century as its popularity spreads far beyond Baltimore.

Screen Painting Pioneers - Johnny Eck, Alonzo Parks, Ben Richardson, Ted Richardson, Richard Oktavec, Al Oktavec, Frank Cipolloni, Leroy Bennett, Greg Reillo, Charles Bowman, and my grandfather Leo Smith, My grandfather used to take a blank window screen sit up on an easel and sketch what he saw through the screen, then paint the screen in bright colors. Years after he stopped doing house screens, he bought an old Green Hornet an ugly little car, but he used to set up at flea markets and sell antiques and junk, not wanting to have to unload his car after each show, (we called them shows LOL I guess because we showed our junk) anyway, getting up in years he was tired of unloading after each show, so he painted the side windows from inside the car and painted a screen for the back window, he could see through to use his rearview mirror, but no one could see all the valuable antiques he left in that old Hornet between "shows!" During that time his house had a screen that matched views from his own property out in the county, and his car had a picture of his dog, "Poncho," a grouchy little Chihuahua.

Affordable Housing-Ground Rent

Affordable Housing-Ground Rent

Baltimore was laid out in 1729 as a shipping point for tobacco, and later grain products. Shipbuilding, grain mills, and associated mercantile attracted ship builders, carpenters, sea captains, sailors, and craftsmen. Those industries later brought in workers for packing houses, iron and steel works, and factories. Everyone needed housing. The wealthy, the middle class, and the working class all lived in rowhouses.

Some were elegant large homes with fan lighted doorways and elaborate interior details, while others were simple 4 room, two bay wide homes.

A system called ground rent made home ownership affordable. The concept of ground rent (as well as the row house style itself) came from England. When the eldest son of a noble class family inherited his father's land, they could not, by law, sell the property. The estate earned income from tenant farmers. As cities grew larger, land owners realized they could make more money by building and selling homes, but renting the land under the homes.

Today, the arcane system is still in place. Ground rents earned land owners a dependable 6% on their investment. The low annual payments were (and still are) easily affordable for homeowners.

Bowed front row house with columns | Source These simple homes are on a very narrow street, once an alley. | Source

1790-1800

In 1796, flour merchants Thomas McElderry and Cumberland Dugan built long wharves in the area now known as the Inner Harbor. Row houses built right on the wharves stood 3 1/2 stories and featured hip roofs, dormer windows, and high English basements. The upper stories were residential while the high basement provided commercial space.

Builders and speculators began to erect similar rows of elegant homes with commercial space below and residential space in the upper stories. Many of these homes were quite grand, three bays wide with an entry hall, and two rooms deep with a kitchen wing or back building and pantry.

Up until 1799, nearly half of these buildings were made of wood until brick was stipulated by law. Very few of the old wooden homes survive.

From 1790-1800, the population of Baltimore doubled. Housing was needed for new arrivals in the prosperous shipping town. Houses built for workers and the lower classes rose to 2 1/2 stories and were 2 bays wide without the side hall featured in more upscale housing.

Grand homes were built along main thoroughfares while middle-class homes were built on side streets. The smallest houses were built on alleys with fanciful names like Happy Alley, Strawberry Alley, and Whiskey Alley. These smaller units were 17' wide with basement kitchens. Some 1 1/2 story houses were as small as 10 1/2' to 12' wide.

The smaller houses were often homes for Baltimore's large African American population which included freemen and slaves. At the time, rural slave owners hired out slaves to businessmen. Urban slaves had greater freedom than their rural counterparts as they lived without a master. Frederick Douglas claimed that the density of population prevented the abuse that rural isolation made more possible. Freemen hired out slaves, and white laborers of similar professions and economic station lived on the small integrated blocks or alleys. Simple yet attractive 3 bay wide, 2 story row-houses

Kitchen Extension in Back

Utilities in Early Dwellings

Fireplaces stood in most rooms of the grander row houses. It was not until the late 18th century that cast iron stoves provided heat. The large heating surface of stoves provided greater warmth than fireplaces. Coal replaced wood as an economical and efficient fuel.

Water came from hand pumps stationed along the streets. Upscale rows featured hand pumps in the back yards, thanks to a new reservoir created in 1807.

Before 1840, indoor plumbing was nonexistent. People used chamber pots. Night soil carters carried off the waste. Foul odors and disease, including typhoid and cholera, were common. In the mid-1800s, piped water became available by subscription, and water closets (a small room with a toilet) flushed into the harbor.

Mount Vernon Greek Revival Row Houses

Greek Revival and Neoclassical

After the War of 1812, a new prosperity encouraged a building boom. The city became a manufacturing center and in 1827, the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road created new markets for manufacturers. Baltimore became a city of foundries, lumber mills, glass makers, machine works, and by the 1840s, steam engine manufacturers.

Mount Vernon Place was built around the Washington Monument, built to memorialize George Washington. The beautiful monument based on a Greek Doric column design influenced the construction of homes in the area.

Fashionable row houses built around small parks reflected simple, elegant Greek and neoclassical designs.

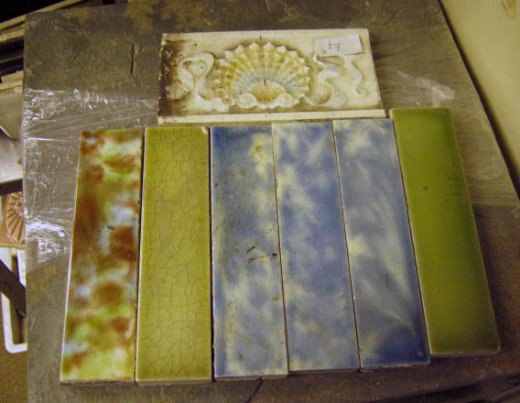

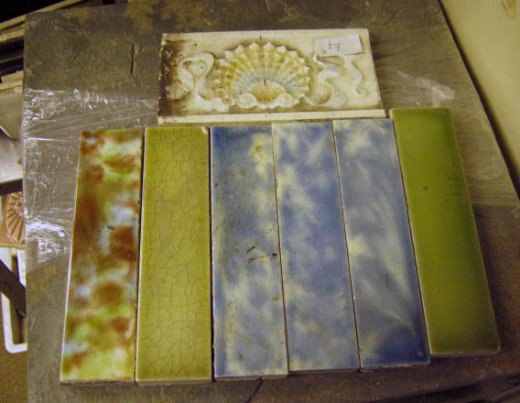

These beautiful old tiles once lined a row house entryway or vestibule. | Source

Italianate

After the plain facades of neoclassical designs, a new interest in ornamentation followed Victorian styles. Rowhouses in the mid-1800s featured elaborate designs including bold projecting cornices, tall narrow windows, and exterior ornamentation.

Romantic sensibilities and new building technologies introduced beautiful new designs. Cast iron structured frames allowed for taller buildings. Decorative cast iron embellishments including columns, capitals, and window treatments could be assembled at a factory and carted to the construction site.

Even smaller ones employed the newer, more fashionable styles with tiled entry halls and vestibules. Average row houses featured stained glass door surrounds and transoms, stamped metal cornices, and tin ceilings in the kitchen. Edward Gallagher built modest versions of the finer Italianate homes in brown or red brick. The flat-roofed homes featured stamped designs on cornices.

Italianate Circa 1875

Edward Gallagher built these modest versions of Italianate style homes so that people of average means could afford to live in style. | Source

Edward Gallagher built these modest versions of Italianate style homes so that people of average means could afford to live in style. | SourceQueen Ann

Queen Anne style mixed architectural styles of the past and incorporated ideals of the Aesthetic Movement, a concept that rejected the mass production of the Industrial Revolution and Victorian tastes. From 16th and 17th century English styles, builders borrowed cottage style forms including partial stucco, 1/2 timbering along with red brick.

The picturesque Gothic style featured asymmetrical facades and windows, along with natural trim or first-floor facades made of rock.

Belvedere Terrace and Eutaw Place employed the concepts of craftsmanship and an appreciation of nature by using molded brick, colored glass, terra-cotta panels, brownstone trim, and arched windows and doors. Undulating bow fronts and turrets reflected the aesthetics interest in medieval history.

Large homes offered a back garden that could be seen from a large dining room window.

The mixing of styles - Queen Anne Style

A picturesque look at the varied roof line, windows, and facade of these beautiful homes. | Source

Large porches and second story bow front windows make these row homes very attractive.| Source

Renaissance Revival

The Renaissance Revival of the late 19th century saw row houses with flat roof lines and white marble lintels and sills. Iron cornices decorated the roofs with swags of leaves and rosettes. Some swell fronts were interspersed with flat fronts, all with white marble steps from a nearby quarry.

In 1905, open porches were added to the front of the better row homes. As the elite moved out to single homes in suburban areas, builders attempted to offer owners similar options like the large, columned front porch with small front yards. Second story bay windows with swags and decorated cornices made these homes beautiful.

English Cottage Style  Slate roofs and varied building materials including half timbering in a beautifully landscaped setting. | Ednor Gardens all stone row houses with slate roof and sun porch. | Source

Slate roofs and varied building materials including half timbering in a beautifully landscaped setting. | Ednor Gardens all stone row houses with slate roof and sun porch. | Source

Early 20th Century

In the early 20th century, daylight row houses were 2 rooms wide so that all rooms but the bathroom had windows. As the middle and upper classes left the congestion of the city for suburban cottages, a new interest in natural beauty encouraged builders to compete by creating new styles.

English style groups of row houses offered to landscape, wide covered porches, steep slate roofs, Tudor half-timbered stucco second stories, dormers, and varied entryways. Some of the cottage styles offered houses built out of several materials and included stucco, brick, and rock.

Edward Gallagher Jr opened his new development called Ednor Gardens and used rock blasted from the building site in house designs. Picturesque roof lines, sun porches, and varied windows gave each home an individual look. During the housing boom of the 1920s, Gallagher and his sons offered homes with built-in garages.

Unlike row house developments of the past, corner houses no longer featured commercial space for a store or bar. New zoning regulations and development covenants ruled against commerce, additions, or changes made to outdoor trim color. Some covenants had racial restrictions in the deeds.

The Great Depression of the 1930s created a decline in-home sales. Real estate values and housing development plummeted.

By the early 1940s, World War II brought new jobs to large Baltimore employers like Bethlehem Steel and Glenn L. Martin. A new American neoclassical style based on colonial Williamsburg offered simple, inexpensive home designs with bay windows and wide end units.

After World War II, the housing demand and the GI Bill's home loan program encouraged large-scale row house building in the suburbs in places like Loch Raven Village and Edmonson Avenue.

The middle class moved to single homes outside the city while inner city high-rise housing projects crowded low-income people into large prison-like structures that warehoused the poor. A declining industrial base caused large-scale job loss for the working class in Baltimore.

Baltimore Rowhouse in Ednor Gardens

Late 20th Century Re-Hab

As Baltimore's oldest neighborhoods deteriorated due to age, overcrowding, and absentee landlords who neglected their properties, large areas of the city became derelict. The oldest neighborhoods, like the 120-170-year-old row houses in Federal Hill and Fells Point, became slums. By the late 1960s, some of the oldest houses near the waterfront were condemned in order to provide space for an extension to I-95. But a visionary group of preservationists petitioned the government for historical status and, in 1967, had Federal Hill and Fells Point listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It took 10 years to dissuade the government to move the path of the highway, but the movement drew attention to the historic Baltimore water-front and sparked an urban renaissance for older city row homes.

Mayor William Donald Shaefer and Housing Commissioner Robert C. Embry offered up 5,000 abandoned houses for $1.00 a piece. A city development office offered technical and financial help with a city backed loan program for the restoration of older homes.

Today, many of Baltimore's historic row house neighborhoods have become enclaves of young professionals. Real estate values in areas close to the water escalated and have remained high, even during the recent economic downturn. Other row house neighborhoods around the city remain affordable, comfortable, and efficient choices in a variety of communities.

© 2012 Dolores Monet