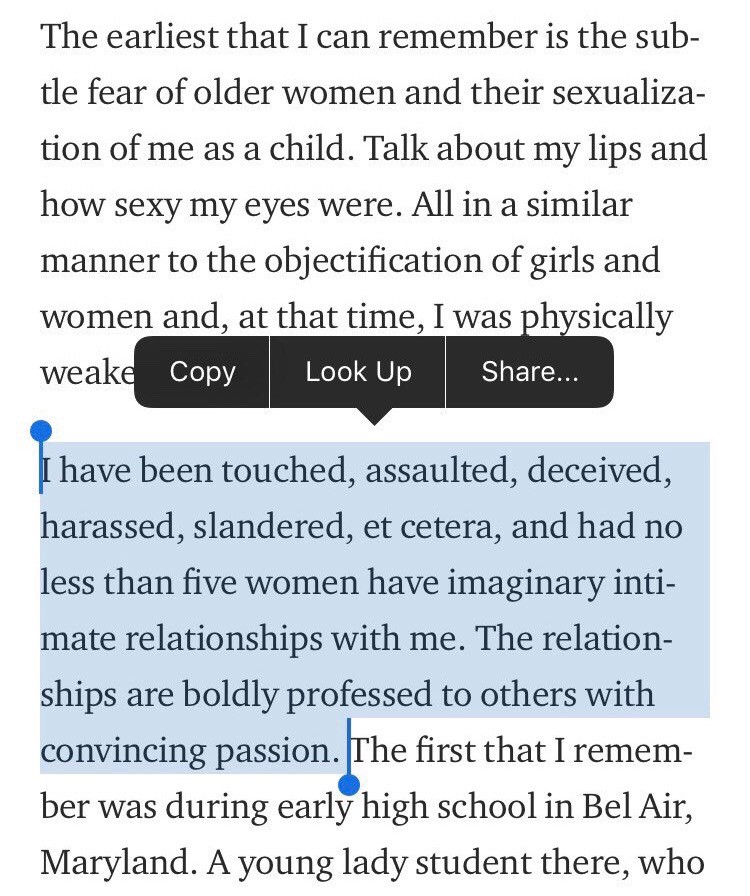

Michael Wood

Sgt. Michael A. Wood Jr.

On Wednesday morning, former Baltimore police Sgt. Michael A. Wood Jr. woke up to find his phone full of thousands of new Twitter notifications.

A few days earlier, the 35-year-old Marine corps veteran had begun tweeting about his 11 years in the Baltimore Police Department — and all the things he had seen that he now felt needed to be shared.

Wood was in the police force in Baltimore from 2003 to 2014 and retired due to a shoulder injury, the Baltimore Police Department human resources department told BuzzFeed News. While on the force he earned a number of honors and awards, and his LinkedIn boasts four glowing, watermarked recommendations from lieutenants and captains on the force.

"I had this idea of a 'Good Cop,'" Wood said, "that was a kind of Robocop. Someone without human bias. I tried to separate my emotions from the job, I formed a wall between myself and the suspects. I thought that was how you enforce a law equally."

Since then, he told BuzzFeed News, he has realized that the only way to serve the law fairly is to use as much empathy as possible in the job. To be able to see civilians and suspects as human.

"A hero isn't a cop who instantly fires off his gun, a hero isn't the cop who shot Tamir Rice," Wood said, referring to the 12-year-old in Cleveland who was shot in 2014 by an officer who thought his toy gun was real. "A hero is the guy who hesitates before shooting, the guy that takes the risk of being shot himself for the sake of not killing an innocent person."

From the beginning of his training, Wood said he encountered an "us and them" mentality — "them" being primarily young, black men in the impoverished areas he was patrolling.

As a trainee, Wood was placed in Gilmor Homes, the public housing development in West Baltimore where years later Freddie Gray died due to injuries related to his arrest. Wood mostly made drug-related arrests in that neighborhood he said, keeping his eye out for black men ages 16 to 24.

"I saw all young black males as potential criminals. In my mind, and in the mind of my fellow officers, they were the ones who committed the crimes," he told BuzzFeed News.

"A hero is the guy who hesitates before shooting, the guy that takes the risk of being shot himself for the sake of not killing an innocent person."

"When you're a trainee they know you're faking being a cop," Wood said of the residents in the notoriously impoverished neighborhood. "We did drug arrests and everything, some of the officers were very aggressive. But we had no idea what we were doing, and they knew it."

Wood speculated that being a trainee in a rough neighborhood often produces particularly aggressive officers. This helps cause a divide between officers and civilians from the beginning, he said.

After he was a trainee, Wood served his first few years in a neighborhood called Pig-town. "It was there that I saw the detective slap that woman, and where I saw officers kicking handcuffed suspects on the ground," he said. He was then transferred to an upper middle class, majority white neighborhood, to be closer to his daughter's school district in Pennsylvania.

"I'm not realizing how messed up this was until right now," Wood told BuzzFeed News, "but I used to go to other officer's posts, to black neighborhoods, just to make arrests so I could meet my stats," he said, referring to the amount of arrests he was expected to perform each week.

"They knew that judges and court officials lived in that neighborhood. If I locked up the judge's 18-year-old son for drugs or whatever, things could get really bad for me."

"I used to go to other officer's posts, to black neighborhoods, just to make arrests so I could meet my stats."

It wasn't until Wood got transferred to "the knockers," otherwise known as the Violent Crime Impact Division — his first time in plainclothes, doing raids and writing search warrants — that he really began seeing "the dirty shit," as he called it.

"It started before my time with this unit that would piss and shit on the beds and clothes of the people whose houses they raided," Wood said. "They did it as a calling card like, 'Ha ha this is what we do.' Then other people years later would do it to be like 'Ha Ha' back at the other cops."

It had nothing to do with the people whose homes they were defecating in, Wood alleged, it was an in-joke among police officers. "The first time I saw it I was like, 'Won't they get caught?' But someone told me they blamed it on K9 dogs they brought."

Wood said he didn't even think of its effect on the civilians. "I just thought of it as an asshole thing to do, but I didn't put myself in the victims' shoes," he said. "The mind separates that all for some reason."

It wasn't until Wood was transferred into covert surveillance, he said, that he really began to "soften up."

"I would stay in a vacant building all day. I would smell people's cooking, hear them talk about their problems." It was during these hours that Wood said he began to see the people he had been surrounded by for years through a lens other than that of a cop.

"Sometimes I would see a drug dealer put something away quickly and run to a car. I'd think something was going on, but then he would pull his kid out of the car and take him home." He said it was then he realized that he had only seen the people in these communities at their worst — while they were being arrested or calling 911 — and that it had been preventing him from seeing them as truly human.

When Wood became a sergeant, he said he would often have his officers put on plainclothes and walk through the neighborhoods, chat with the residents about anything that wasn't crime related. "When you take a walk through in plainclothes and you see an old woman asleep on her steps, you see her and get to talk to her, when you drive by in a squad car you don't even notice her because she's not a problem."

Wood described himself as turning into a "progressive, humanitarian, ultra-liberal guy."

He began to notice other officers who targeted young black males for arrests were not aware of what he called the "cyclical nature of crime" — that the reason black people were convicted of more crimes was because they were arrested more often, not necessarily because they committed more crimes. "White people carry drugs on them much more than black people do, precisely because they don't think they'll be arrested for it. It's ridiculous," he said.

He began calling out officers who only pulled over "cute girls," or old ladies with their children because they were scared. He started telling his officers that locking up white people in Baltimore's Eastern District would get them "triple the points," while he himself began targeting white people more than black people "as a baby step toward the way things should actually be."

Wood said his popularity in the force started waning. Then, officers he would normally associate with started talking behind his back, and they still are to this day, he said. "My friends in the department whittled down to a very small list," he said, "but those are the ones who listen. Those are the ones who understand everything I'm doing and saying now."

Jeremy Silbert, a spokesperson for the Baltimore City Police Department, told BuzzFeed News that Wood's allegations were "serious and troubling."

"We hope that during his time as both a sworn member and as a sergeant with supervisory obligations, that Mr. Wood reported these disturbing allegations at the time of their occurrence," Silbert wrote in an email to BuzzFeed News. "If he did not, we strongly encourage him to do so now, so that our Internal Affairs Division can begin an immediate investigation."

Silbert also referred to a letter from Police Commissioner Anthony Batts published in the Baltimore Sun a few days after Wood began speaking about his experiences on Twitter. "My mission when I arrived was to [eradicate corruption] with a renewed sense of purpose and determination," Batts wrote, going on to outline reforms he has made and plans to make.

"Many officers will be unhappy reading these words. Many want me to outright defend the department and say nothing is wrong with the way this organization engages in police work," he continued. Batts concluded by encouraging officers and Baltimore residents to report corruption they observed. "Speak out against the beating of a resident at a bus stop or the selling of narcotics on the back porch of a police station."

Wood, who now plans to go into academia to "sow the seeds of understanding in people before they go into law enforcement," said he thinks the key to changing the "broken system of policing" is education and empathy. He said that ideally, he would want cops to be required to have an education beyond a GED, that they be taught "not just what to think, but how to think." Wood, adding that it might be "silly and cheesy," said he believes this would enable officers to see the flaws in the system and fix them, that a better education might enable them to put themselves in the shoes of the people they serve and protect.

More so than an education, Wood believes that during training officers should be required to spend time with the people in the low-income communities they will be serving, getting to know kids in recreation centers or other situations unrelated to crime. "The whole thing is about policing with empathy," Wood emphasized repeatedly. "That could maybe change everything."

Community outreach programs similar to what Wood is talking about have already been undertaken by police departments in Gary, Indiana, Los Angeles, Boston, and a number of other large cities as a part of President Obama's "21st Century Policing Task Force" — though few of these programs are required for all officers or occur during training.

"I regret the whole mentality I had at that time. I regret falling in line with everyone else," Wood told BuzzFeed News. "Now I just want the police to wake up. I’m not indicting the past; I’m just trying to get things to be different in the future."