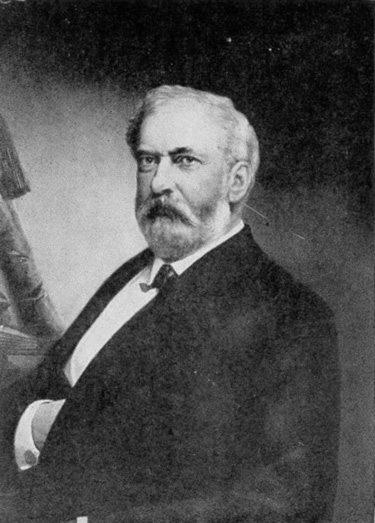

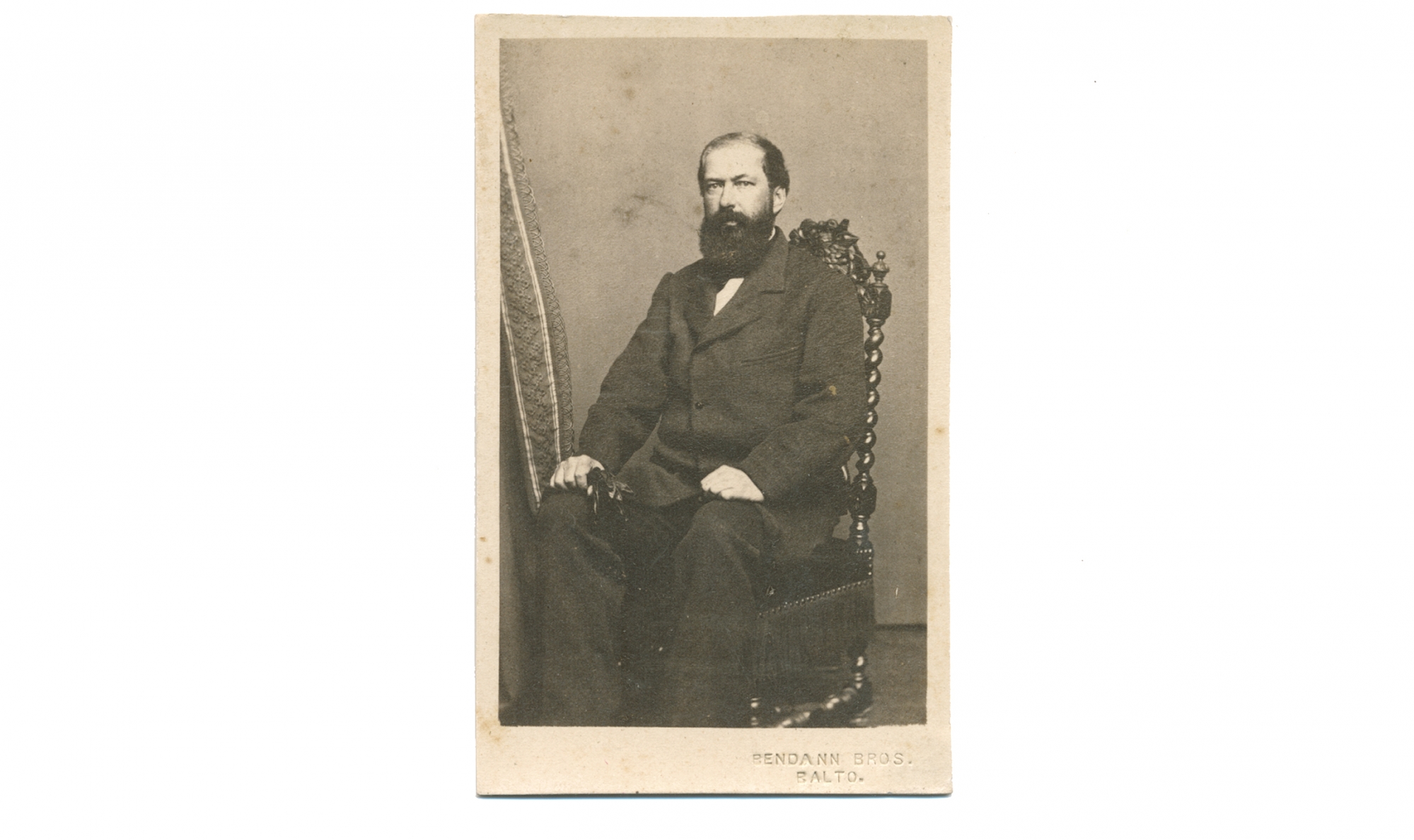

George Kane

Marshal George Proctor Kane - Became Marshal of the Baltimore Police Department on 20 February 1860 Marshal Kane remained in office as head of the Baltimore City police until 27 June 1861

Marshal George Proctor Kane

Police Department

Office of the Marshal

Became Marshal of the Baltimore Police Department on 20 February 1860

Marshal Kane remained in office as head of the Baltimore City police until 27 June 1861

![]()

25 June 1911

When Baltimore’s Police Board Was Sent to Prison

by Matthew Page Andrews

General Cadwallader was replaced in charge of what was essentially the military district of Annapolis and Baltimore in the early part of June 1861 by Maj. Gen. N. P. Banks. General Cadwallader, according to the extremists who were at the time pushing for the continuation of the war, was too indulgent with Baltimore's "disloyal" residents. They also stated that Baltimore was a "hotbed of treason" and that the majority of people there were sympathetic toward the South, if not actively prepared to overthrow the government. A second St. Bartholomew would immediately follow if the 5000 muskets currently bursting around Baltimore were removed, according to The New York Tribune, which was likely the most widely read newspaper at the time. Officers of a passing regiment once forbade their soldiers from drinking any water handed to them by locals out of concern that it might have been purposely tainted by "Rebel" sympathizers. Such was Baltimore's national reputation as a result of the political press of the time.

One of the officers in the regular Army was General Cadwallader. The decision to completely abolish civil law was made by General Banks, a civilian appointed to a military command, which seemed revolting to Cadwallader but was welcomed by Banks. Gen. Banks used informants and spies after being given command in Baltimore to entrap "disloyal" civilians, taking note of individuals who were outspokenly opposing the war and coercing those suspected of harboring Southern sympathizers into sharing their views.

The Maryland legislature adjourned on June 22, 1861, in Frederick, after passing resolutions vehemently opposing the "military despotism" that had been ushered in in the state, declaring that no one's person or property was safe, no home was respected as sacred, and private correspondence was no longer sacred. Following this proclamation, vents moved quickly. Three months prior to the Baltimore mayor and a large number of other notable residents, Gen. Banks was gathering information and preparing to make arrests of citizens starting with the lowest-ranking rider.

The younger generation, who are heavily impacted educationally by a significant influx from the northern states, is unaware that Baltimore, Maryland, was almost as warmly a southern metropolis as Richmond, Virginia in 1860. It had a population of around 200,000, and the vast majority of its powerful residents supported the union up until the idea of coercing the South was floated. They either left Maryland to fight for the Confederate or were out of sympathy with an aggressive war against their southern neighbors when that subject was directly presented to them.

While opposing the war in the heat of April's excitement, Governor Hicks eventually saved himself by submitting completely to federal authority. The rest of the Maryland leaders were marked men, with a few notable exceptions. As an example of this, it should be noted that Chief Justice Taney told Mayor Brown in May 1861 that his [the mayor's] time would come and that his activities were then being closely watched because he was aware that his own arrest had been considered.

Following this explanation, it is simpler to follow and comprehend the events surrounding the arrests of George P. Kane, the most well-known of Baltimore's police marshals and later the city's mayor, as well as the arrest a few days following the news of the city's whole police board.

Remarkable Contrast and Point of View

The Sunday Sun of April 9 of this year hailed Marshall Kane's bravery and composure in defending the Massachusetts Regiment following the firing upon the citizens. He was the one who prevented the federal volunteers' detached companies from perhaps being alienated at the time. Even so, Marshall Kane opposed continuing the war, and the federal government would never pardon him for the telegrams he sent as part of one of numerous activities leading up to and soon following April 19th. The first was a request for information sent in the following words by a Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore railroad official: "Is it true, as claimed, that an attempt would be made to pass the volunteers from New York destined to war upon the South across your train today?"

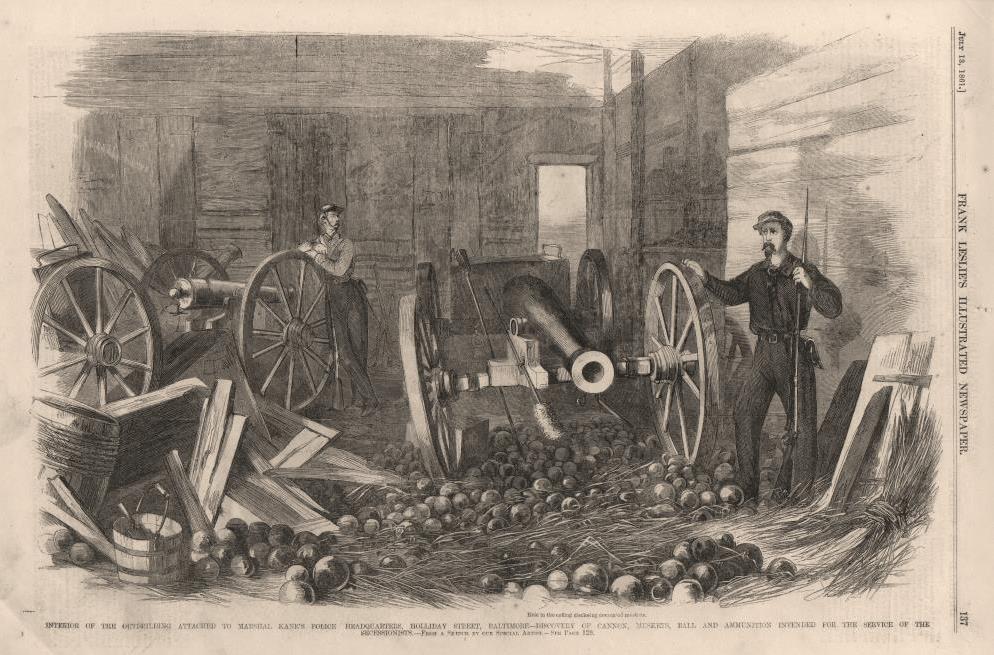

This interpretation of what the call for federal troops was intended to accomplish differed so significantly from that of the federal authorities—at least in Baltimore—that it essentially amounted to evidence of treason against the US government. The language used by the federal government at this point in the conflict can be seen in secretary Cameron's letter to Governor Hicks dated April 18, which claimed that illegal groups of Maryland residents were obstructing the movement of American troops through Maryland on their way to the defense of the capital. Marshall Kane also sent a message to Bradley T. Johnson asking for volunteers to aid Maryland in fending off beaters who had turned Baltimore's streets "red with blood." Kane was arrested and imprisoned as a result of these telegrams and his opposition to the use of military authority without approval from the police board. On June 27, this story of Kane's arrest was written by the local paper's editor in chief and later by a staff member of the Sun, beneath a black headline in 10-point type that was quite sensational in Baltimore at the time.

The Arrest of Marshall Kane

The long-simmering plot against Baltimore has finally materialized, resulting in the eradication of all civil liberties and the establishment of a military despotism. Early this morning, a rumor that Marshall Kane had been apprehended by the troops and sent to Fort McHenry spread across our village, causing considerable anxiety. The confirmation of the story increased the enthusiasm, and throughout the morning, a sizable number of the marshal's acquaintances visited his office and the police commissioners' rooms eager to learn more. The realization of this act has stirred up a lot of emotion and practically all of our citizens' attention, who are gathered around every corner talking about it despite the fact that it has long been anticipated due to the threats made. The arrest took place this morning around 2:30 a.m. when a company of soldiers, made up of some Maryland volunteers from Camp Carol and some Pennsylvania Regiment soldiers stationed on Federal Hill, marched as quietly as they could from the federal camp to 136 St. Paul Street, the Marshall's home, with troops guarding every entrance. The marshal was asked to show up. He opened the door after coming down the stairs looking dapper and half-dressed when he was suddenly grabbed and dragged into a waiting carriage in front of the home. He was not told why he was being held, and he was also not allowed to speak to his wife or any other members of his family. When the military gathered around the carriage and one of the commanders sat down inside, he hastily made his way to Fort McHenry. It goes without saying that his wife and family were understandably extremely scared by his abrupt detention and worried that violence would be used against them. It took them a few hours before they learned of his temperament. “ The military took all the police they encountered and forced them to march with them as a measure of precaution against a rescue attempt for the marshal. One of Mr. John B. Egerton's neighbors was concerned by the noise as they drew up to his home and stooped to the door. He was placed in charge with them until Col. Kane's person was safe. The officer in charge told the cops who had been detained that they may now resume their duties when the troops arrived at Federal Hill. The announcement that General Andrew P. Banks was about to impose martial law and that he had appointed Col. John R. Kenley of the Maryland Volunteers as the provost marshal was posted on newspaper bulletins around 9 AM, which may have served to heighten the excitement generated by Marshall Kane's arrest. Col. Kenley called on the police commissioners at fifteen minutes before eleven o'clock and presented them with the following paper, declaring that they were now superseded in their role as such because he had previously been supposed to take full control of the police force. General Banks gave the following order on June 27, 1861: "Headquarters Department of Annapolis. I am hereby appointing you Provost Marshal in and for the city of Baltimore in accordance with instructions I received from the department of war at Washington on June 24, 1861, to Col. Kenley, commanding first Regiment, Maryland volunteers. You will start your duties right away at the city's police headquarters, and after informing the mayor of your appointment by reading him this order and the proclamation that is included with it, you will immediately start working with other officers in the police department to put the police law that the Maryland legislature has provided for the administration of the city of Baltimore into effect. "I am most humbly yours, etc.," said N. P. Banks, the commanding general of the Annapolis department. While denying the legitimacy of his [Col. Kenley's] action, the commissioners noted that they should offer no resistance to General Banks assuming control of the marshal's office despite their refusal to recognize General Banks' authority to act in this manner. They stated that they should file a written protest against this procedure. A meeting was conducted after inviting the mayor to the board, and in the meantime, Col. Kenley made his way to the marshal's office. There, he informed Deputy Marshal Gifford that he had arrived to assume command and invited the various captains of police to report to headquarters. The following order was subsequently issued and given to them: "Special Order number 1 "Office Provost Marshal, Baltimore, "June 27, 1861. "By order of Major-General Banks, commanding the Department of Annapolis, I assume intake commands of the police force of the city of Baltimore, the superintend, and to execute and cause to be executed the police law provided by the Maryland legislature for the government of the city of Baltimore, with the assistance of the subordinate officers of the police department. According to Col. J. R. Kenley's directive, the provost marshal of Baltimore is commanding the first Maryland Regiment. Col. Kenley requested verbally that the board call a meeting of all the captains of police to meet him at the marshal's office. Informing Col. Kenley that the board did not acknowledge the legitimacy of Gen. Banks' actions on the property, the president asked him to put his recent request in writing on behalf of the board. He retracted the request and declined to do so. After that, he said that he would be heading straight to the Marshal's Office. In response to a request from the board, the president and mayor went to the marshal's office and gave the deputy marshal orders to not interfere with Col. Kenley's actions and to hold off on taking any action until he had been informed of the board's opinions.

THE POLICE BOARD’S RESOLUTION OF PROTEST

The whole subject having been maturely considered, the following preamble and resolutions were unanimously adopted, viz.: “whereas, the laws of the state of Maryland gives a whole and exclusive control of the police force of the city of Baltimore to the board of police, organized and appointed by the Gen. assembly; and not only are the said board bound to exercise the powers in and to discharge the duties imposed upon them, but all other persons are positively prohibited, under heavy penalties, from interfering with them in so doing; and, “Whereas, there is no power given to the board to transfer the control over any portion of the police force to any person or persons whomever other than the officers of the police appointed by them, and pursuance of the express provisions of the law; and acting under their orders; and, “Whereas, by the orders of Maj. Gen. Banks, an officer of the United States Army, commanding in this city, the marshal of police has been arrested, the board of police superseded, and an officer of the Army has been appointed provost marshal and directed to assume the command and control of the police force of the city; therefore be it “Resolved, that this board do solemnly protest against the orders and proceedings above referred to of major – Gen. Banks as an arbitrary exercise of military power not warranted by any provision of the Constitution or laws of the United States or of the state of Maryland, but in derogation of all of them. “Resolved, that whilst the board, yielding to the force of circumstances, will do nothing to increase the present excitement or obstruct the execution of such measures as major – Gen. Banks may deem proper to take on his own responsibility for the preservation of the peace of the city of Baltimore and of public order, they cannot, consistently with their views of official duty and of obligation of their oath’s of office, recognize the right of any of the officers and men of the police force as such to receive orders or directions from any other authority than from this board. “Resolved, that in the opinion of the board the forcible suspension of their functions suspends at the same time the active operation of the police law and puts the officers and men off duty for the present, leaving them subject, however, to the rules and regulations of the service as to their personal conduct and deportment and to the orders which this board may see fit here after to issue when the present illegal suspension of their functions shall be removed. “Charles Howard, Pres., “William H. Gatchell, “Charles D. Hinks, “John W. Davis, “George William Brown, Mayor and ex- officio members of the board.”

DISBANDING OF POLICE FORCE

Considering that the laws of the state of Maryland give the board of police, organized and appointed by the General Assembly, a whole and exclusive control of the police force of the city of Baltimore; and not only are the said board bound to exercise the powers in and to discharge the duties imposed upon them, but all other persons are positively prohibited from doing so," the preamble and resolutions that follow were unanimously adopted. "Resolved, that this board do solemnly protest against the orders and proceedings above referred to by Major General Banks as an arbitrary exercise of military power not warranted by any provision of the Constitution or laws of the United States or the state of Maryland, but in derogation of all of them." Resolved, that while the board will submit to the force of circumstances and take no action to heighten the current commotion or obstruct the execution of any measures that major-general Banks may deem necessary to take on his own responsibility for the preservation of the peace in Baltimore and of public order, they are unable to do so in a way that is consistent with their views of official duty and the obligations of their oaths of office. In the board's opinion, the forcible suspension of their duties suspends the active enforcement of the police law at the same time as taking the officers and men off duty for the time being. They remain subject, however, to the service's rules and regulations regarding their conduct and demeanor as well as any orders that the board may subsequently issue when the current illegal suspension of their duties is lifted. George William Brown, Mayor, William H. Gatchell, Charles D. Hinks, John W. Davis, Charles Howard, President, and ex-officio board members.

HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF ANNAPOLIS FORT MCHENRY 1 JULY 1861.

Following the conclusion of their meeting, the police commissioners and the mayor sent a notification to the police captains of the various stations at 2 o'clock informing them of their decision to dissolve the force and giving them instructions on how to go about doing so. The men were subsequently called to the station house and informed that their employment as police officers had been terminated effective immediately. The board of police's refusal to comply with Gen. Banks' military orders swiftly and supinely caused the latter to become extremely irate. Baltimore was thereafter made aware of her complete helplessness and the futility of any civil rights-related protests, which were now at least nominally but undoubtedly actually suspended. As a result of this decision, the announcement of the police board's arrest and detention on General Banks' command stunned the city early on July 1st, 1861. Nearly all business was shut down, and groups of people congregated all over to talk about the news of the most recent incident, as it was known to be. The Pennsylvania Infantry under Col. Morehead made the arrests of the police commissioners early in the morning. At before 3 AM, the soldiers made their way to John W. Davis' house near Federal Hill, where they arrested him and transported him to Fort McHenry under guard. They then went to Charles D. Hanks' house on W. Lombard Street. Despite Mr. Hanks' deteriorating health, he was imprisoned and sent to the fort. The soldiers then proceeded to Charles Howard, the board president's home on Cathedral Street, where they detained both him and William H. Gatchell before transporting them to what Baltimoreans were now referring to as "the American Bastille." Any members of these commissioners' families who may raise suspicion were likewise temporarily detained. General Banks announced the arrests at 8 o'clock, providing an explanation that, in Judge Brown's words and later on, "did not explain":

“Nath P. Banks

“Major – General Commanding.”

Artillery and Troops in City Squares

An excerpt from a reliable historical account of military activity in and around Baltimore reads, "At an early hour this morning the movements among the military indicated something new for the "defense of the capital," as infantry and artillery were hastily moved from the various camps into the city. As three companies of Col. Pratt's 20th New York Regiment were marched inside these structures and are currently maintaining a rigorous guard over them, a part of Col. Cook's Boston light artillery were stationed in exchange Place, fronting the customhouse and post office on Lombard Street. No one is allowed to enter the customs building unless he can prove that he is there on business, and everyone traveling to or from the post office must follow the guards' authorized route while dodging their bayonets. Col. Lyle's Regiment and the rest of the Boston artillery were also stationed in Monument Square, however it is unclear what their specific roles were at the time.

"The remaining regiments in and around the city were all on guard at various spots around the steamboat words and at other sites. A unit of the 20th New York Regiment has also been stationed in front of St. Patrick's Church on Broadway. The 13th New York Regiment, under the command of Col. Abel Smith, dispersed its camp this morning at 6 a.m., marched to the McKim's Hill on the York Road, and set up camp there. The officers took control of the ancient mansion home as their headquarters. Soon, squads of this Regiment were dispersed throughout the eighth Ward of the "rebels," looking for weapons. Though the soldiers claim that the statements made by union men to Gen. Banks indicating that an organized movement was about to be made to attack several camps and Fort McHenry and that they had been ordered in to prevent it and to protect the "loyalist" were the cause of the large military demonstration, there has been much speculation regarding its cause. ”

At the time, the sight of troops from other states restraining the citizens of Baltimore in this way upset Marylanders descended from colonial forebears of revolutionary records so much that further hundreds left the city for the South. Today's well-known Maryland Club members and others have told the writer that the Boston Artillery's presence in Monument Square on one July 1861, as they were making their way to work, so sparked their ire that they immediately prepared to leave and go see if they could express it to the Southern Confederacy's armies.

![]()

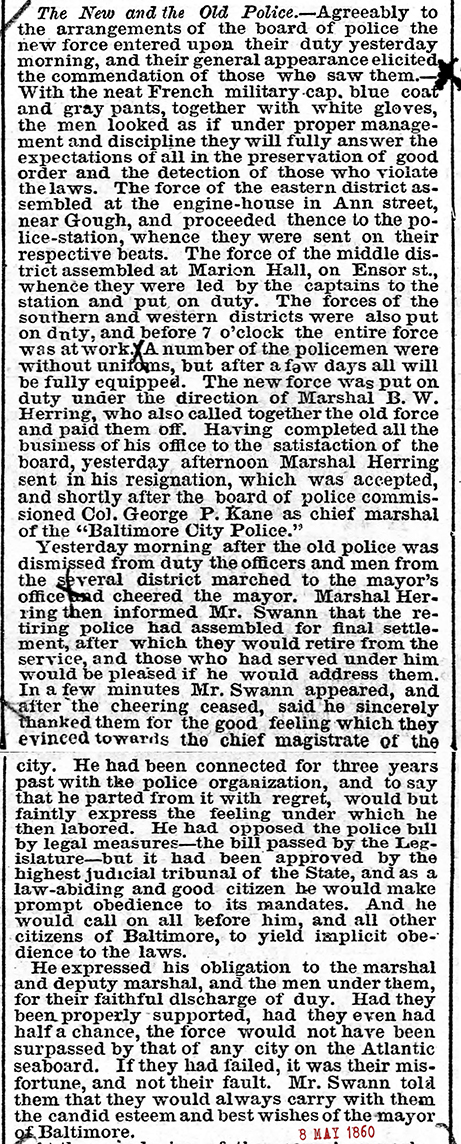

8 May 1860

The New and the Old Police

Baltimore Sun Paper

Tuesday - 8 May 1860

about the events of

Monday - 7 May 1860

![]()

27 Feb. 1861

I visited the friends of the President-elect with whom I had been on the cordial and close terms for many years while I was in Washington on Thursday last for a strictly private affair. When I mentioned the rumors that had reached me about an intended republican display by some parties here, the conversation accidentally turned to the public functionary being contemplated passing through our city. In my opinion, this display would be offensive to the majority of our people, and Mr. Lincoln's association with it or having it accompany his transit through Baltimore would invite determined punishment. I never suggested the President-elect avoid traveling in public through Baltimore, nor did I ever consider such a scenario. In fact, I refrained from making any recommendations in the area and instead focused on expressing my opinion that having an escort or appendage like the one the rumor had suggested would be unwise and expose it to criticism from the public, which could and undoubtedly would have been interpreted as a premeditated discourtesy by Baltimoreans toward the incoming president.

The Police Board considered all aspects of the anticipated visit by the President-elect, and they determined that all essential precautions for maintaining order on the occasion were mature and more than adequate. The Board agreed with the views I had expressed when I informed them of the conversation I had in Washington that was mentioned. I offer this justification because some press outlets have allowed inaccurate interpretations of what I did in this situation to reach the public. GP Kane and Marshall

![]()

![]()

George Proctor Kane served as a Marshal for the Baltimore City Police Department from August 4, 1817, to June 23, 1878. His work as the Baltimore Police Department's Marshal during the Pratt Street Riots in 1861 is what made him most famous. Others claim that Nicholas Biddle, an escaped slave from Pottsville, Pennsylvania, was responsible for the first deaths of the Civil War. Little details about Mr. Biddle's life exist because he managed to escape enslavement. According to what we know, his parents were slave owners in Delaware around 1796 when he was born. He eventually fled slavery and settled in Pennsylvania. Two stories about Mr. Biddle are related; it was standard procedure for fugitive slaves to change their names in order to evade capture. Some claim that Nicholas left for Philadelphia and worked as a servant for Nicholas Biddle, a successful businessman and the head of the Second Bank of the United States. In this tale, a dinner gathering of businessmen and industrialists was held in Pottsville to commemorate the first successful operation of an anthracite-fueled blast furnace in America. The former slave and the banker traveled there. The aide continued to reside in Pottsville. Another story has it that Biddle moved from Delaware to Pottsville right away and worked as a maid at the hotel where the celebration supper was held, when he first encountered and was very impressed by the well-known Biddle.

In any case, Nicholas Biddle was living in Pottsville, Pennsylvania, by 1840, and it is known that he adopted the name of a well-known Philadelphian. He did odd occupations to make ends meet, such as selling ice cream and oysters on the street in the summer and winter, respectively. According to the 1860 U.S. Census, he worked as a "porter." Biddle made friends with members of the Washington Artillerists, a local militia unit, and spent the next 20 years participating in their training exercises and outings. Despite the fact that Black Americans were not allowed to serve in the militia, the company members liked Mr. Biddle and treated him as if he were one of their own, giving him a uniform to wear. President Lincoln issued a call for volunteers to serve a three-month tour of duty at the start of the Civil War and the fall of Fort Sumter on April 15, 1861, in an effort to quell the uprising in the South. The Washington Artillery, which had maintained a state of readiness unlike other antebellum militia groups, was one of the first companies to answer Lincoln's call to arms. The Washington Artillerists left Pottsville by train two days later to join the conflict. Nicholas Biddle, a 65-year-old man, joined the group of men who would assist Captain James Wren, the company's commanding officer. Five companies, totaling about 475 men, were mustered into the service of the United States on April 18, 1861, and were sworn in at Harrisburg. All but Nicholas Biddle, who was unable to join the American Army because he was Black American. The men departed on an urgent order to protect Washington, DC from alleged Confederate threats. However, at the time, there were no continuous rail services that would take them straight through Baltimore; as a result, when trainloads of soldiers offloaded from one train in the hopes of simply switching trains in Baltimore, which just so happened to be the largest city in the slave state of Maryland, they encountered hostile mobs of pro-Southern sympathizers, and unlike their hopes of hopping off one train and quickly loading onto another were dashed. A little more than a mile to the west, at the Camden Yards Stations, the businesses that were unloading at Pratt Street Station had to travel. In order to meet the firms and board their trains from Camden Station to their destination, the groups marched up Pratt from their place on President Streets. The journey would not be simple, though; almost right away, they encountered a number of local mob members who started jeering at them. Now, these American soldiers fighting on American soil had to dodge more than just derogatory insults and remarks; they also had to dodge bottles, tiny stones, and entire or partially broken cobblestone bricks that were being thrown at them by older youngsters and adults. The very street that was guiding them from one station to the next, where passenger and box cars were waiting to help them in their departure, was being pried up and cleared of these cobblestone blocks.

One of the larger cobblestone bricks that had been flung by a member of the crowd eventually knocked Mr. Biddle to the ground. The soldiers were largely evading and avoiding the projectiles that were being launched in their direction up until this point. But, they were horrified to see their buddy Nicholas Biddle lying in the middle of a Baltimore Street, bleeding to death from a head wound so deep that the skull could be seen through it. The troops walking past and above him were friends who had gotten to know him well and had developed a tight bond with him over time. With that, two things rapidly got going. First, they banded together to assist Biddle leave and obtain medical attention. The soldiers started mounting a defense against the onslaught as soon as Biddle was taken out of the picture. At first, there was only pushing and shoving, but when a member of the crowd opened fire on the soldiers, the militia was forced to retaliate. Up until the arrival of the police, they continued to use what modern police would refer to as "suppression fire." Nicholas Biddle basically became the first person to bleed from a very serious, life-threatening wound after the citizens revealed his skull through the cut. He would survive the injury, but he would live with the scar from it. It was apparently the first and most serious injury he had that day. The American Civil War began as a result of this harm being brought on by hostile activities, which granted these individuals the right to self-defense. The little children present in the crowd made a very straightforward chore complicated.

One of the historical mysteries surrounding the Baltimore Police Department is why the primary police force was located near the conclusion of the troops' intended route rather than at its beginning. By failing to respond to Marshal Kane's repeated telegrams asking how many troops were en route to the President Street location and when they would arrive, the management of the P.W. & B. be railroad is partially to blame for the riots, according to the record collection of the unrest that was published 19 years after the events by George William Brown, Baltimore's mayor in 1861. As a result, by 1030 on the morning of April 19, the police could do no better than send their main According to Mayor Brown's version, such action was appropriate despite the fact that a sizable crowd had gathered at both stations as early as 9 AM and that the separatist flag, which is a circle of white stars on a field of blue, was being flown by the crowd and Pres. Street station. Passengers who were traveling from the North on the P.W. & B were hauled one by one and by four force teams to Camden station, where they disembarked and boarded Baltimore and Ohio trains to continue their journey to the historic national capital. According to a Police Department history written in 1888, "it was here that the attack was feared" because the change of automobiles happened at this time.

But why there, where the troops would have been marched more than a mile by enraged onlookers who were already jeering Jefferson Davis? Cheering for President Lincoln for an hour and a half when he was President of the New Confederacy? A Pennsylvania Militia troop (the first defenders) that had been trained in North Baltimore was stoned by a crowd as it marched south to catch a train for Washington just the day before, sparking a smaller riot that did not result in any fatalities. On April 18 in Baltimore, the police provided the initial defenders with increasingly ineffective security while they were on foot. Why then, on April 19, did marshal Kane appear to change his mind and conclude that the six Massachusetts and others would be secure while aboard the cars while they were being transported from Pres. Street station to Camden station?

Mayor Brown later determined that the six Massachusetts et al. would have been more imposing and consequently safer if they had marched as a body of 1700 men from one station to the next (in his memoirs of the incident, published in 1887). Col. Edward F. Jones, the sixth Massachusetts commander, is said to have prepared a similar order for marching into Baltimore, but it was abandoned because "someone had plunderered," Mayor Brown concluded, firmly implying that some PW and be officials had. Kane's following detention at Fort McHenry and Fort Warren. Abraham Lincoln made the choice to sneak through Baltimore in February 1861 on his route to Washington to be inaugurated in order to avoid a potential assassination attempt. His decision was influenced by a number of considerations, including his role as Marshal of Police and his sympathy for the South. Notwithstanding his politics, I find this portion a little odd: Abe Lincoln would leave ahead of time to confuse those attempting to assassinate the president, while his wife and children kept to the normal schedule so as not to alert the assassins that he was aware of their preparations. I'm not sure why these plans didn't work out completely, but it appears to me like he was endangering his wife and children. Which may mean one of two things: either he wasn't as in love with Mary Todd as we might have believed he was, or he didn't think he was in danger, as other accounts of same plot suggest. He also ordered Marshal Kane to protect and accompany Mary Todd Lincoln upon her arrival in Baltimore in February 1861 while she and her children were en route to the inauguration of their husband and father, who had gone before them. This action supports his denial of the existence of a true conspiracy. The excursions and Kate Warren's involvement in them are both somewhat true. Documents suggest that Mrs. Warren, who was a widow at the time and responded to a call for Pinkertons, was immediately hired by Allen Pinkerton because he was attracted by the opportunities. Mrs. Warren apparently piqued interest in Abe Lincoln during the Abraham Lincoln protection since her records indicate she worked for Pinkerton's from the time of her initial interview in 1856 until 1861, when she was often photographed donning a Union soldier costume.

![]()

George Proctor Kane (August 4, 1817 – June 23, 1878) was an American politician and policeman. He is best known for his role as Marshal of Police during the Baltimore Riot in 1861 and his subsequent imprisonment at Fort McHenry and Fort Warren. His position as Marshal of Police and his southern sympathies were two of many factors in the Abraham Lincoln's decision in February 1861 to pass through Baltimore surreptitiously on his way to Washington to be inaugurated, in order to avoid a possible assassination attempt. Despite his politics, This part is a it odd to me, in order to throw off those plotting to assassinate the president, Abe Lincoln would head out ahead of schedule, but so as not to let on to the assassins that he was on to their plans, his wife and kids maintained the regular schedule. I am not sure how these plans went down 100%, but to me, it seems as if he was putting his wife and kids at risk. Which says one of two things, a) he wasn't as in love with Mary Todd as we might have thought he was, or, as other stories of this plot suggest he didn't believe he was in danger. Something else that support his not believing there was a true plot was that he had Marshal Kane provide protection and escort for Mary Todd Lincoln upon her arrival to Baltimore in that February 1861 while she and her offspring were on their way to the inauguration of their husband and father, who had preceded them. There is some truth to the trips, and in fact to Kate Warren's having been involved. Records show that in 1856 Mrs. Warren's a widow at the time answered an ad to become a Pinkerton, so intrigued at the possibilities Allen Pinkerton hired her on the spot. Apparently during the Abe Lincoln protection detail; Mrs. Warren sparked an interest in good ole honest Abe, because her records show eras having worked for Pinkerton from that initial interview in 1856, until 1861 when she was pictured several tines wearing the uniform of Union soldier

Kate Warren was the first female detective, in 1856, in the Pinkerton Detective Agency and the United States.

George Proctor Kane

George Proctor Kane (1820–1878) was mayor of Baltimore, Maryland, from November 5, 1877, to his death on June 23, 1878. He is best known for his role as Marshal of Police during the Baltimore riot of 1861 and his subsequent imprisonment at Fort McHenry and Fort Warren without the benefit of habeas corpus. His position as Marshal of Police and his southern sympathies were two of many factors in Abraham Lincoln's decision in February 1861 to pass through Baltimore surreptitiously on his way to Washington to be inaugurated, in order to avoid a possible assassination attempt. Despite his politics, Kane was instrumental in providing protection and an escort for Mary Todd Lincoln on her arrival in Baltimore in February 1861 on her way to the inauguration of her husband, who had preceded her.

Early Political Life

Kane was born in Baltimore in 1820 and at an early age entered the grain and grocery business. He was commissioned an ensign in the Independent Grays, a military organization, and afterward commanded the Eagle Artillery and the Montgomery Guards. He was later colonel of the First Maryland Regiment of Artillery.

Mrs. Kane was Miss Anna Griffith, daughter of Capt. John Griffith, of Dorchester County, Maryland.

Kane was (as a matter of course, since he had several political offices) much identified with the politics of the City of Baltimore. He was originally an adherent of the old Whig Party and an active and enthusiastic supporter of Henry Clay, as shown by the fact that he was Grand Marshal of the parade of the Whig Young Men's National Convention held at Baltimore May 1, 1844, which ratified the nomination of Mr. Clay for the Presidency of the United States. The future Mayor of Baltimore was then but twenty-four years old. In 1847, during the famine in Ireland, he was very active in relief work. At this period he was president of the Hibernian Society. With several others, Mr. Kane purchased the old 'H'-shaped, massive domed "Merchant's Exchange" (designed by famous architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, built 1816–1820, the largest building in America at the time, also known as the "Baltimore Exchange", later site of the present U.S. Customs House, built 1903-05) on South Gay Street between Water and East Lombard Streets and sold the property to the United States Government itself, which, upon remodeling the buildings, which had always housed Federal courts, customs, post office and a branch of the First Bank of the United States along with other city hall/municipal offices in one wing (until "Old City Hall" – the previous Peale Museum on Holiday Street was acquired in 1830 and occupied to 1875) and also included those of lawyers, brokers, shipping companies and other maritime businesses in another wing. They now continued to use them for years exclusively as the U.S. Customs House and Post office (until a new U.S. Courthouse was constructed at the northwestern corner of East Fayette Street and North Street (now Guildford Avenue) in 1859-60, dedicated by 15th President, James Buchanan. Later supplemented by a larger central Post Office/U.S. Courthouse of Italian Renaissance Revival architecture with eight small towers and large central clock tower) was constructed in 1889 on the east side of Battle Monument Square, facing North Calvert Street. He was also active in the old volunteer "Baltimore City Unified Fire Department" "confederation" system (organized in the 1830s to 1859) and president of the Old Independent Volunteer Fire Company. Historians credit Colonel Kane with suggesting and campaigning for a "paid", professional steam-powered fire department system which was later finally organized in the city in 1858-1859, as a definite expansion of municipal governmental functions with advanced improvements.

In 1849 he was Appointed Collector of the Port of Baltimore.

In the 1850s, Baltimore was a city mired in political corruption and mob violence with occasional riots between rival gangs known as "Plug-Uglies" and others (similar in look and feel to the situation in Civil War-era New York City portrayed in director Martin Scorsese's 2005 film "Gangs of New York" based on the novels of Herbert Asbury). The new Baltimore City Police Department had just been organized a few years before in 1857 along with the Baltimore City Fire Department also just the year before in 1859 to eliminate some of the violent clashes between competing for rival volunteer fire companies which had served since the 1770s. As a result, the General Assembly of Maryland (state legislature) embarked upon a reform movement, which included finding a strong new "Marshal of Police" (chief). Kane filled the bill, becoming Marshal of Police in 1860, under newly elected reformist Mayor George William Brown. According to famous city historian J. Thomas Scharf, "It is impossible to overrate the change that the organization of an efficient police force wrought in the condition of the city." Mayor George William Brown later wrote that the entire police force "had been raised to a high degree of discipline and efficiency under the command of Marshal Kane.

Kane and the Baltimore Plot

In February 1861, Detective Allan Pinkerton, (1819-1884), working on behalf of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad, uncovered what he believed to be a plot to assassinate President-elect Abraham Lincoln as he journeyed through Baltimore on his way to Washington to begin his first term. Pinkerton presented his findings to Lincoln, which included his belief that Kane, recently appointed Marshal of Police in Baltimore by newly elected reformist Mayor George William Brown, was a “rabid rebel” who could not be trusted to provide security to Mr. Lincoln while in Baltimore. Pinkerton believed that Kane could participate in the plot merely by under-performing in his duties, thereby giving others ample opportunity to carry out their plans, and claimed to have overheard a conversation in a Baltimore hotel in which Kane indicated that he had no intention of providing a police escort for Lincoln. Baltimore at this time was a hotbed of pro-Southern sympathies. Unlike other cities on the President-elect's itinerary, including New York, Philadelphia, and Harrisburg, Baltimore had planned no official welcome for Lincoln. Pinkerton’s information regarding Kane, along with other information discovered by him, his operatives and others, led to the President-elect's decision to follow the detective’s advice, changing his travel plans and passing through Baltimore surreptitiously nine hours ahead of his published schedule.

In 1868, in response to stories then circulating in the press about the Baltimore plot, Kane wrote a lengthy account of his view of the events of Feb. 21–23, 1861. He believed the President and his family would arrive in Baltimore as planned on the Northern Central Railroad at its Calvert Street Station (later after 1950, the site of the Baltimore Sun's offices and printing plant, by Bath Street and the overhead Orleans Street Viaduct) at 12:30 pm on February 23, and depart on a 3 pm train from the Camden Street Station on the southwest side of town. That left two and a half hours to fill in a City in which the President got only about 1000 votes, and most of those, according to Kane, from “the very scum of the city.” In other words, there were no sizable numbers of upper-crust Lincoln supporters who might be counted on to rally around the President in a public display, and entertain him, as had continually happened on the President’s previous stops coming East in New York, Harrisburg, and Philadelphia on his triumphal parade through the North from his home in Springfield, Illinois. Kane came up with a plan, which he implemented, in which John S. Gittings, who owned the Northern Central Railroad, would travel to the village of Maryland Line (on the Mason–Dixon line, a border between Maryland and Pennsylvania), get on the President’s train, and accompany him to Baltimore. Once in Baltimore, the train would make an unscheduled stop at North Charles and Bolton Streets, where Kane would meet it with carriages that would carry the new President and his family to Gittings’ mansion on Mt. Vernon Place. There a sumptuous meal would be served. This plan avoided the Calvert Street Station altogether and kept the President-elect largely out of view of possible "rabble-rousers." According to his own account, Kane carried out his plan exactly, with the only exception being that the new President was not aboard the train. In actuality, President-elect Lincoln having possibly already anticipated the possible plot through the information secured by and presented to him by the noted new detective Allan Pinkerton, (1819-1884), and Samuel Morse Felton, Sr., (1809-1889), President of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad, and confirmed by some other sources. So after leaving his party in Harrisburg, Lincoln boarded a night express back to Philadelphia with Ward Hill Lamon, (1828-1893), his trusted aide, and traveled that evening back east and had his car attached to the end of the last evening P.W. & B. train running southwest to Baltimore arriving at the east-side President Street Station at 3 a.m. With his lonely night car pulled slightly west along Pratt Street to the Camden Station|Camden Street Station, where it was held for a short while then placed at the end of a Baltimore & Ohio Railroad train to Washington where the sleepy President-elect and his bodyguard (and possibly another armed man arrived at the B. & O. Station in the Nation's Capital at 6 a.m. taking up residence in the noted Willard's Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue three blocks from the White House of out-going 15th President James Buchanan. Newspaper accounts variously described Mrs. Lincoln and the boys being met by an unruly crowd in the Calvert Street Station disappointed in not seeing the new President were reported in various ways. They later also followed on the B. & O. later that day. Kane, in his memoirs of the Plot and 1861, claimed this was erroneous and that Mrs. Lincoln was not jostled by the crowd, but that she had already alighted and left the station before they assembled.

![]()

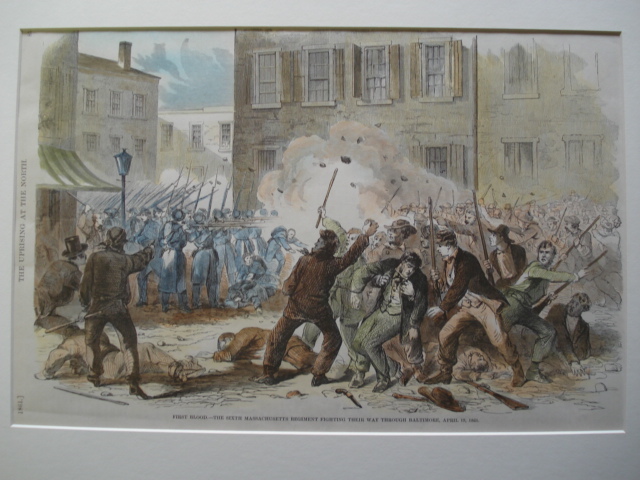

Baltimore Riot of 1861 - Part 1

Pratt & President Street Riots

The Civil War’s First Bloodshed

Main article: Baltimore Riot of 1861

On April 18, 1861, two companies of US Artillery and four companies of militia arrived from Harrisburg at the Bolton Station, in the northern part of Baltimore. A large crowd assembled at the station, subjecting the militia to abuse and threats. According to the mayor at the time, “An attack would certainly have been made but for the vigilance and determination of the police, under the command of Marshal Kane.”

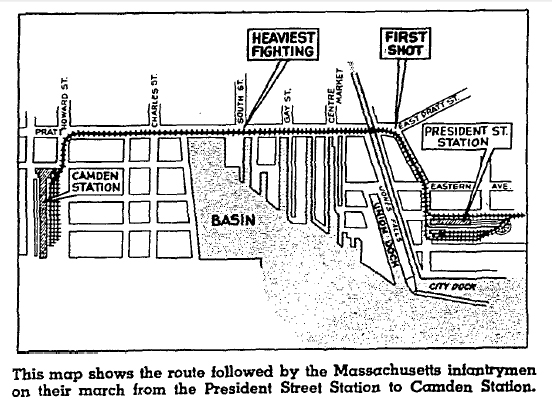

Kane and others in Baltimore, knowing the fever pitch of the city, sought to learn about plans for other troops to pass through town, but their telegrams north asking for information were largely ignored, probably at least partly because of Kane's well-known Southern sympathies. So it was on the next day, April 19, that Baltimore authorities had no warning that troops were arriving from Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. The first of the troops had arrived at the President Street Station, on the east side of town, and had successfully traveled the one-mile distance along East Pratt Street via horse-drawn rail cars, to the Camden Street Station (now near modern "Camden Yards"/Oriole Park baseball stadium) the west side, to continue to Washington. There a disturbance ensued that soon brought the attention of Marshal Kane. His police, (according to Mayor Brown's later memoirs), prevented a large and angry crowd “from committing any serious breach of the peace.” Upon hearing reports that the mobs would attempt to tear up the rails leading toward Washington, Kane dispatched some of his men to protect the tracks.

Meanwhile, the balance of northern troops encountered greater difficulty traversing Pratt Street. Obstructions were placed on the tracks by the crowd and some cars were forced back toward the President Street station. The soldiers attempted to march the distance along Pratt Street, and according to Mayor Brown were met with “shouts and stones, and I think an occasional pistol shot.”

The soldiers fired back, and the scene was one of general mayhem. Marshall Kane soon appeared with a group of policemen from the direction of the Camden Street Station, “and throwing themselves in the rear of the troops, they formed a line in front of the mob, and with drawn revolvers kept it back. … Marshal Kane’s voice shouted, “Keep back, men, or I shoot!” This movement, which I saw myself, was gallantly executed and was perfectly successful. The mob recoiled like water from a rock.” By the time it was over, four soldiers and twelve civilians were dead. These were the first casualties of the American Civil War.

Even though Kane appears to have executed his duties faithfully during these events, and wrote an official account defending his actions (Public record defense by Marshall George P. Kane of his actions on April 19, 1861, in dealing with the riot in Baltimore that "shed the first blood of the Civil War"), there is no question that he was very pronounced in his Southern sympathies. After the riot, Marshal Kane telegraphed to Bradley T. Johnson in Frederick, Md. as follows:

"Streets red with Maryland blood; send expresses over the mountains of Maryland and Virginia for the riflemen to come without delay. Fresh hordes will be down on us tomorrow. We will fight them and whip them, or die."

This startling telegram produced immediate results. Mr. Johnson, afterward served as a general in the Confederate States Army, commanding the Maryland regiments, came with volunteers from Frederick by a special train that night and other county military organizations began to arrive. Virginians were reported hastening to Baltimore.

![]()

Baltimore Riot of 1861 - Part 2

Pratt & President Street Riots

The Civil War’s First Dead

16 April 1961

There Were the 12 Baltimoreans Killed in the Bloodied Pratt Street Riots

There Were the 12 Baltimoreans Killed in the Bloodied Pratt Street Riots

The most significant Civil War action in Baltimore was the Pratt Street Riots of Friday, 19 April 1861, which directly caused 17 known deaths, at least 50 injuries and 7 recorded the arrest.

Most of the fighting took place along President Street, from near the harbor north to Pratt Street, and along Pratt St., west to Light Street. The violent action would last from approximately 11 AM to 12:45 PM and most involved 200 and 20 New England Militiamen, some of whom carried and fired muskets, and a mob of Baltimore civilians including a few Maryland Militiamen that were out of uniform and were reported to number anywhere from the 250that initially arrived to as many as 10,000 and who had fired a few pistols but fought mainly by grappling with passing Militiamen or by hurling paving stones.

Of the 600 or so officers and men of the 6th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, Volunteer Militia, who passed from the President Street Station 1.1 miles west to the Camden Station, in route to Washington, four were killed and about 35 wounded. The dead soldiers, all of which were enlisted rank, were Addison O. Whitney, Luther C. Ladd, Charles A. Taylor, and Summer A. Needham. The last named died with “little resistance” in a Baltimore hospital about a week after the riots and during the 19th-century style operations on his fractured skull.

Of the 1000 unarmed Pennsylvania Militiamen and about 100 additional members of the 6th Massachusetts, including the Regimental Band, who arrived at the same time, none made it through the mob around President Street Station on their journey, and only one died of injuries sustained. His name was George Leisenring, and he succumbed to his injuries about a week later after he returned to Philadelphia.

Many Baltimoreans were wounded, and 12 were killed – James Clark, William R. Clark, Robert W. Davis, Sebastian Gill, Patrick Griffith, John McCann, John McMahon, Francis Maloney, William Maloney, Philip S. Miles, Michael Murphy, and William Reid.

At the time, and off and on ever since, many Baltimoreans were most outraged by the death of Mr. Robert Davis, a 36-year-old dry-goods merchant & innocent bystander that may have cheered for the Confederacy but did not join in the fighting. Mr. Davis was shot by someone on the 6th Massachusetts train shortly after it pulled out of Camden Station. Upon being hit by the round he was heard to cry out, “I am killed!” as he fell, and the next day a Baltimore Coroner's jury decided that he had been “ruthlessly murdered, by one of the militaries.” Mr. Davis’s funeral was elaborate, but his murderer was never named, charged, or prosecuted.

Two of the dead civilians, Patrick Griffith, and William Reid, both young black men that had been employed in the area. Patrick Griffith was employed on one of the oyster slopes that was tied up on the docks near Pratt and Light Streets. William Reid was employed by a Pratt Street establishment described only as the “Greenhouse” and was “shot through the bowels while looking from a doorway on Pratt Street.”

The ages, addresses, occupations, specific circumstances of death and last rites of the other Baltimore casualties have apparently never been recorded, although those who fell in the Pratt Street Riots turned out to be the first fatality victims of a hostile action in the Civil War (no one was killed during the action which it ended four days earlier at Fort Sumter. South Carolina.)

The most thorough contemporary accounts of the Riots, and Baltimore newspapers, state that the police arrested “great numbers” afterward. Only seven were apparently ever named anywhere – Those were, Mark Kagan and Andrew Eisenbrecht, charged with “assaulting an officer with a brick,” Richard Brown and Patrick Collins, “throwing bricks, creating or contributing to a riot” William Reid, “severely injuring a man with a brick” J. Friedenwald, “assaulting an unknown man,” and Lawrence T. Erwin, “throwing a brick on Pratt Street.”

These Seven Constitute Another Civil War “First.”

The Troops for Massachusetts and Pennsylvania responding to Abraham Lincoln’s 15 April 1861 call for volunteers, and many Baltimoreans in slave-holding Maryland interpreted that to be an effort to recruit an army to invade such seceding “sister states” as Virginia. A Confederate Army recruiting office flourished at Marsh Market: a process session mob of about 800 had roamed Charles Street on the night before [18 April] and more than one African American had been flogged for cheering the Republican President in public.

So, the Baltimoreans in the Pratt Street Riots were as much Pro-Southern as they were simply Pro-Maryland or simply outraged by the alleged violation of state sovereignty by another state's militia (an idea suggested in “Maryland! My Maryland! The official state song that was inspired by and written shortly after the Riots by Ryder Randel, a native Baltimore English teacher who at the time was living in New Orleans).

And so, the seven Baltimoreans arrested turned out to be the first Civil War partisans of either side who suffered official legal action for their pains. Of them, only one, Lawrence T. Erwin was convicted and “held for a sentence” so far as contemporary accounts, historians and memoirs reveal. His sentence, if any, was unrecorded.

History of the Baltimore Police Department

Marshal Kane and The Pratt Street Riots - 19 April 1861

One of the historical accounts of the Baltimore Police Department and of Marshal George Proctor Kane; explains that It was useless for any arrests to be made because, not one officer could be spared to put those arrested in lock-up. It seems, too; that although the department had been reorganized about a year earlier under Marshal Kane with an intent to rid the department of corruption, and any affiliation with the political group, known as the; “Know Nothings” and other political elements of those times; The police had no patrol wagons. Patrol wagons wouldn't come to Baltimore until 1885 Since the main body of the police detailed to maintain order during the malicious passage was about a mile away at Camden Station, or in route to the scene of the fighting during most of the rioting. it is perhaps remarkable that as many as seven arrests could have been made.

The secessionist flag was described as having a circle of eight white stars on a field of blue… Why the main body of police was at the end of the troop's projected route; instead of at its beginning; is still something of a mystery. The recollection of the riots that were published nearly 20 years after the event by George William Brown; [Mr. Brown was the Mayor of Baltimore during the riots on the day in 1861] He lays part of the blame on the management of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad. The company failed to answer Marshal Kane’s repeated telegrams that asked how many troops were in route to the President Street Station and when they would be expected to arrive.

The secessionist flag was described as having a circle of eight white stars on a field of blue… Why the main body of police was at the end of the troop's projected route; instead of at its beginning; is still something of a mystery. The recollection of the riots that were published nearly 20 years after the event by George William Brown; [Mr. Brown was the Mayor of Baltimore during the riots on the day in 1861] He lays part of the blame on the management of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad. The company failed to answer Marshal Kane’s repeated telegrams that asked how many troops were in route to the President Street Station and when they would be expected to arrive.

So, by 10:30 AM on the morning of 19 April 1861, the police could do nothing better than send their main body – “a strong force” – to Camden Station. Such action was proper, explained the former Mayor, even though large crowds had assembled at both stations as early as 9 AM and even though the Secessionist Flag – [a circle of eight white stars on a field of blue] – was displayed by the throng at President Street station. Passengers who arrived from the north on the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad. Then customarily stayed on the cars at President Street if they were bound for Washington, and the cars were hauled one by one, by horse teams of four, to Camden Station, where the passengers got off the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad cars and boarded the Baltimore & Ohio railroad cars before continuing on to the National Capital. “As the change of cars occurred at this point,” a Police Department history published in 1888 remarked, “It was here that the greatest risk of attack was feared.”

But why at Camden Station, to which the troops would have been pulled more than a mile through angry spectators who had already been hurrahing Jefferson Davis, President of the New Confederacy, and jeering President Abraham Lincoln for an hour and a half?

Only the day before, a lesser Riot resulting in no deaths, but many injuries, began near the Bolton Station when another troop of Pennsylvania Militia the 1st Defenders, detrained in North Baltimore, and was stoned by a mob as they marched south to board a train at Camden Station headed for Washington DC.

The police supplied more or less effective protection for the 1st Defenders while they were afoot in Baltimore on that day the 18th of April 1861 So Why then; did Marshal Kane, apparently reverse his strategy just one day later on the 19th of April 1861. what had him decide, the 6th Massachusetts, would be safe, while on the cars as they were pulled from the President Street Station to the Camden Station.

Mayor Brown later decided in his memoirs of the riot, published in 1887 that the 6th Massachusetts would have been more imposing, therefore safer, if they had marched as a body of seventeen hundred men from one station to the other. Just such an order for marching through Baltimore was apparently prepared by the 6th Massachusetts Commander, Colonel Edward F. Jones, but it was abandoned, “Someone had blundered,” Mayor Brown concluded, strongly hinting that, that someone was a The Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad executive.

The logic of hindsight suggests that the main body of police should have met the train at President Street Station; and that adequate details of officers should have escorted each of the horse drawn cars of soldiers to Camden Station As it happened, the first nine cars of the thirty-five car troop train, hauled Colonel. Jones: and seven of his eleven Massachusetts companies from President Street, across Pratt Street and down Howard Street to Camden Station with little if any, police escort, and still, they made the trip without any serious mishaps. The crowds hissed a little but were only able to throw stones at the last car, and Mayor Brown, who by this time had arrived at Camden Station from his law office, thought that maybe the nine cars were all there would be.

The tenth car was halted at the Pratt Street bridge over Jones Falls by a wagon load of sand that the mob dumped in its path; some anchors (perhaps as many as eight) that were dragged from nearby ships across the tracks by several African American seamen and a motley barricade of lumber and paving stones that were handy because the streets by happenstance were under repair at that point.

The tenth car then turned around retreating toward the President Street Rail Road Station, where the mob had swelled to roughly 2000, and where some police had arrived (from outlying districts apparently; not from the main body of police, at Camden Station as the 200 and 20 or so soldiers detrained and lined up in single file There effort to march to Camden Station became unlikely, as formations were blocked by a lot of men flying the secession flag so they reformed into a double file did an about face, and marched in the opposite direction; conceivably inspired to dive into the harbor, and swim West toward Light Street.

The mob, having savagely choked a Union Sympathizer who had tried to tear down the Secession Flag; circled the soldiers and halted the de-facto retreat. The troopers then fell in by platoons four abreast; and with police help; wedged a path north on President Street The gang with the Secession Flag, marched ahead of them and savagely beat two more union sympathizers who tried to tear down their banner. They then ran alongside them, using militia ranks Part of the crowd behind the 6th Massachusetts column began to throw stones, one of which felled a trooper named William Patch, who was then beaten with his own musket.

The 4 companies – C, D, I. and L. – Then began either “to run” or march, “at the double quick” presumably on orders from one; or all of their Captains; who were named Follansbee; Hart; Pickering; and Dike Two more soldiers were knocked down at President and Stiles Streets; possibly by an iron, or one of the, “queer missiles” a term used at the time to describe a chamber pot which was a pot used to hold human waste, at a time before indoor plumbing These, pots of urine and human feces were thrown by Baltimore women into the mob, according to the 1936 reminiscence of Aaron J. Fletcher, the last survivor of the Civil War 6th Massachusetts.

Mr. Fletcher is the only direct account that even suggest women were involved in the riots. (A romantic story, written in 1865, alleges that a Baltimore prostitute named, Ann Manley saved the 6th Massachusetts regimental band by guiding them away from the President Street Station by back alleys; But most accounts state that the police protected the musicians.

At about the Time the Troops Turned the Corner into Pratt Street, at Any Rate, Someone Fired the First Shot.

E. W. Beatty, of Baltimore, fired that shot from the crowd, according to opinion that seems to be based on the opinions of Confederate Officers with whom he later served before he was killed in action. One of the 6th Massachusetts soldiers fired the first shot, according to contemporary newspapers accounts that attributed the information to a policeman identified only as “number 71.” By that time Mayor Brown had heard that a mob had torn up President Street using the cobblestone/brick as missiles and had quickly advanced to the bridge where he met the New Englanders and joined them in their March at the head of the column as far back toward Camden’s Station as Light Street.

Mayor Brown’s account states that he slowed the soldiers pace, (they also had to pick their way through the haphazard barricade at the bridge), that Captain Follansbee said, “We have been attacked without provocation,” and that he, Mayor Brown, then replied “You must defend yourselves” The troopers, of whom about 60 carried muskets, then began to fire in earnest in volleys; according to the newspapers; some of those rounds were fired over their shoulders, and helter-skelter; according to Mayor Brown; definitely not in volleys, according to Aaron Fletcher’s recollection. (Although he was in Company E, which passed safely through in one of the nine cars).

The First Baltimorean Hit (in the groin) was said to have been Francis X. Ward.

A Unionist newspaper in Washington, quoted Colonel Jones the next day as saying that Mayor Brown, had seized a musket, and shot a man during the March. Mr. Brown later wrote that a boy he had handed him a smoking musket, which a soldier had dropped, and that he immediately handed it to a policeman.

The mayor must have found the Pratt Street riots quite embarrassing. Then 48 years old, he had been elected in October of 1860, on a reform ticket; he dedicated to absolving Baltimore of its nickname, “Mob Town,” and had helped, put down the Bank of Maryland riots in 1835; He believed in freeing the slaves gradually but felt that slavery was allowed by the Constitution, and that the south should be allowed to secede in peace

He was summarily arrested by the Federal Military in September of 1861, and imprisoned until November of 1862 from 1872, until the year before his death in 1890; he served as Chief Judge, of the Supreme Bench, of Baltimore City He was defeated in a campaign for Mayor in the year; 1885.

When Mayor Brown left the Massachusetts infantrymen near Pratt and Light Streets; most of the casualties had fallen; the fighting having been heaviest near South Street the Baltimore dead; and wounded; were mostly bystanders

According to most Baltimore accounts; because the running soldiers allegedly firing to the front, and sides, and not at the hostile mobs behind them, which may have been as small as 250 men according to the “Tercentenary History of Maryland.”

A historian who took notable exception to the bystander's only version was from that of, Mr. J. Thomas Scharf; author of the “Chronicles of Baltimore;” in which he describes an “immense concourse of people” that to a man, threw paving stones at the troopers from in front of them

Before the column Reached Charles Street Marshall Kane, and about forty of his police, had finally arrived from Camden Station, and threw a cordon around the soldiers “HALT MEN OR I'LL SHOOT” The Marshal is supposed to have cried; as he and his men; brandished their revolvers the mob heeded, to the Marshal's warnings and halted their actions

That evening, Marshal Kane telegraphed friends to recruit Virginia rifleman to defend Baltimore from further invasion by Union Militia In June, after Gen. Benjamin Butler; “occupied” Baltimore with other Massachusetts troops; the police Marshal was also arrested, and imprisoned He was released in 1862 and “went to Richmond, Virginia;” apparently by an informal agreement, and apparently served the Confederacy during the war He died at the age of 58 in 1878; just seven months after he was elected as Baltimore's 26th Mayor.

The 6th Massachusetts had left Baltimore by 1 P. M. on that 19th day of April 1861; short of its dead, and some of it's wounded, who were cared for in Baltimore hospitals, or temporarily buried at Green Mount Cemetery, and it’s regimental bands men, who along with the 1000 unarmed Pennsylvania volunteers, were more effectively protected by the police from the two attacks at THE President Street Station from mobs which had increased to as many as 10,000 persons, from the initial count of 250, according to Mr. Scharf’s chronicles.

The Pratt Street Riots of 1861 occurred on the Anniversary of the Revolutionary War's Battle of Lexington; a coincidence which both Northern, and Southern propagandist made notably of the former. The civic leaders of Baltimore called half-heartedly for, "Law and Order" in their speeches at Monument Square on that afternoon, ordering, Railroad Bridges burned north of the city, and persuaded President Lincoln to route future Washington defenders through Annapolis

Much as the city might protest that its sovereignty had been violated, the rights appeared to the North to be a pro-Confederate outrage and it is not difficult to understand why, the Federal Government, soon decided to clamp down on the city.

The 6th Massachusetts was in Baltimore three more times during the war, it's survivors were honored here on several occasions, It’s reception on the 19th of April, 1861, caused far-reaching repercussions, though including the ironic turnabout in Baltimore, which saw Unionist mobs roughing up secessionist on the streets; as soon after the riots as May, of 1861

![]()

The Fort Sumter Bombardment took place from 12 April 1861 thru 13 April 1861 during which there were no deaths, that said after the battle, a Southern Soldier died while experimenting around with some of the weapons seized when the Union army left.

Kane's Arrest

However, after days of excitement and suspense, the upheaval subsided, and soon General Benjamin Butler, commander of the Massachusetts state militia, with a strong Federal force of the 6th Massachusetts and several other regiments from other states, took possession of Baltimore’s Federal Hill by night during a driving rainstorm, May 10, 1861, where he erected extensive fortifications. For the rest of the period of the war, Baltimore was closely guarded by Northern troops. Within the year, the city was surrounded by a dozen or more heavily fortified earthen embankment forts making the city, the second-most heavily fortified city in the world at that time, next to Washington, D.C., the Nation's Capital.

Marshal Kane remained in office as head of the Baltimore City police until June 27, 1861, when he was arrested in the dead of night at his house on St. Paul Street by a detachment of Federal soldiers and taken to Fort McHenry. He was moved from Ft McHenry to Fort Lafayette in New York, Fort Columbus in New York, and, finally, Fort Warren in Boston. From F. Lafayette he wrote a letter to President Lincoln in September 1861, describing the fever from malaria he contracted at Ft. McHenry and the inhumane conditions at Fort Lafayette. "Whilst suffering great agony from the promptings of nature and effects of my debility I am frequently kept for a long time at the door of my cell waiting for permission to go to the water-closet owing to the utter indifference of some of my keepers to the ordinary demands of humanity." Later he was moved to Fort Warren in Boston. In all, he was confined for 14 months. He was released in 1862 and went to Montreal.

Kane in the Civil War

As the Civil War was beginning, Kane was moved from Fort McHenry to Fort Lafayette, and then to Fort Columbus, New York. From there he wrote to U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward in October 1861 asking for a speedy trial and complaining that the conditions at Lafayette had been so bad that he required medical care for "an affection of the heart which I attribute to the nature of my confinement at Lafayette." This heart condition may have precluded his service later on the field of battle for the Confederacy. Eventually, Kane was released and went to Montreal in Quebec, Canada.

According to a very erroneous (unusual) "The New York Times" obituary of him on June 23, 1878, (then edited by founder Henry Raymond]]), Kane received a commission from General Robert E. Lee’s staff and was with Lee at Gettysburg. This seems unlikely (according to modern research and scholarship); as a letter he supposedly wrote to Jefferson Davis, (1808-1889), President of the Confederate States was on July 17, 1863, just two weeks after the Battle of Gettysburg, and is from Canada, where Kane supposedly offers his services in organizing an expedition against Chicago, Milwaukee, and Detroit. His plan was to destroy all shipping, thus "paralyzing the lake commerce." By November, he writes Davis again from Montreal to report on the failure of a plan to rescue Confederate prisoners at Sandusky Bay in Ohio. In Canada in 1864, Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth, (1838-1865), presented to Confederate officials – including Kane – his plan to kidnap President Lincoln.

In February 1864, Kane ran the Federal blockade and was soon in Richmond. In 1864, he published a broadside in which he exhorted Marylander's in the Confederate States Army to form their own Maryland militias, rather than serve under the flags of other states. On July 20, 1864, he is reported by the "Charleston Mercury" to be “about to cooperate with our forces then near Baltimore, with 15,000 Maryland recruits." On October 8, 1864, he writes again to Davis, offering to recruit Marylander's to form a corps of heavy artillery, a suggestion that was politely declined. In March 1865, he is reported to have been instrumental in acquiring fresh uniforms for Marylander's in the Confederate Army. In the closing days of the war, he is still writing to Jefferson Davis to report on the movement of troops around Danville, Virginia.

After the Civil War

Kane entered the tobacco manufacturing business at Danville, Va. in late 1865. Returning to Baltimore he was appointed to the "Jones Falls Commission" and was elected Sheriff of Baltimore City by the state Democratic Party in the 1873 election.

On October 27, 1877, Kane was elected Mayor of the City of Baltimore having won the Democratic nomination over Ferdinand C. Latrobe, (1833-1911), (grandson of famed architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, (1764-1820), son of civic activist, lawyer-artist, and author John H. B. Latrobe, and nephew of Benjamin Henry Latrobe II, (1806-1878), noted chief engineer and architect, with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad).

George P. Kane was Mayor of Baltimore City but a short time (his then two-year term would have ended November 3, 1879). City Council ordinances receiving his signed approval were not numerous. One appropriated money for repairs to the former Old City Hall on Holiday Street near East Saratoga street, used 1830-1875, (former Peale Museum built and operated 1813-1830 by the famed Rembrandt Peale, [1778-1860]), and transferred this historic building to the City's Board of School Commissioners for the Baltimore City Public Schools system to be used for school purposes. It soon became the site of Baltimore's first African-American (then referred to as "Colored"/"Negro") in the new racially segregated "Colored Schools" established a few years before to the BCPS in 1865. Another Kane-signed ordinance was to give "Authority to condemn and open Wolfe Street from East Monument Street to North Avenue and Patterson Park Avenue from Oliver Street to North Avenue" and was granted. A Council resolution to appoint a committee to visit and urge upon the United States Congress the necessity of constructing a new post-office was approved by Mayor Kane and also an ordinance to accept Homewood Park (a part of the present site of Johns Hopkins University - near Homewood Mansion, a Georgian/Federal style of architecture, constructed 1801-1808, formerly of the Carroll family and later William Wyman's "Wyman Villa" estates) which was signed April 8, 1878. This ordinance, however, was not carried into effect at that time, as JHU did not move from its newly established "temporary" downtown campus on North Howard Street near Little Ross, West Centre and West Monument Streets until after the turn of the century.

Colonel George Proctor Kane died, while serving as the Mayor of his home city, June 23, 1878, a veteran of some of the most tumultuous events and times in the history of the City of Baltimore. His former opponent, Ferdinand C. Latrobe was elected to serve his unexpired term (and began his own long and honored public service career, being elected to seven terms of office, dominating the political life of "The Monumental City" for a quarter-century.

![]()

In 1849 he was appointed Collector of the Port of Baltimore.

In the 1850s, Baltimore was a city mired in political corruption and mob violence with occasional riots between rival gangs known as "Plug-Uglies" and others (similar in look and feel to the situation in Civil War-era New York City portrayed in director Martin Scorsese's 2005 film "Gangs of New York" based on the novels of Herbert Asbury). The new Baltimore City Police Department had just been organized a few years before in 1857 along with the Baltimore City Fire Department also just the year before in 1859 to eliminate some of the violent clashes between competing rival volunteer fire companies which had served since the 1770s. As a result, the General Assembly of Maryland (state legislature) embarked upon a reform movement, which included finding a strong new "Marshal of Police" (chief). Kane filled the bill, becoming Marshal of Police in 1860, under newly elected reformist Mayor George William Brown. According to famous city historian J. Thomas Scharf, "It is impossible to overrate the change that the organization of an efficient police force wrought in the condition of the city." Mayor Brown later wrote that the entire police force "had been raised to a high degree of discipline and efficiency under the command of Marshal Kane.

![]()

The Baltimore Plot

In February 1861, Detective Allan Pinkerton, (1819–1884), working on behalf of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad, uncovered what he believed to be a plot to assassinate President-elect Abraham Lincoln as he journeyed through Baltimore on his way to Washington to begin his first term. Pinkerton presented his findings to Lincoln, which included his belief that Kane, recently appointed Marshal of Police in Baltimore by newly elected reformist Mayor George William Brown, was a “rabid rebel” who could not be trusted to provide security to Mr. Lincoln while in Baltimore. Pinkerton believed that Kane could participate in the plot merely by under-performing in his duties, thereby giving others ample opportunity to carry out their plans, and claimed to have overheard a conversation in a Baltimore hotel in which Kane indicated that he had no intention of providing a police escort for Lincoln. Baltimore at this time was a hotbed of pro-Southern sympathies. Unlike other cities on the President-elect's itinerary, including New York, Philadelphia and Harrisburg, Baltimore had planned no official welcome for Lincoln. Pinkerton’s information regarding Kane, along with other information discovered by him, his operatives and others, led to the President-elect's decision to follow the detective’s advice, changing his travel plans and passing through Baltimore surreptitiously nine hours ahead of his published schedule.