Last November, as Mayor Brandon Scott prepared to announce his former chief of staff as the city’s new top attorney, the head of the Baltimore Police Department’s consent decree monitoring team quietly notified the federal court of a familial relationship.

Ebony Thompson, Scott’s choice for acting city solicitor, is the great-niece of Ken Thompson, the head of the independent group responsible for measuring the police department’s compliance with reforms.

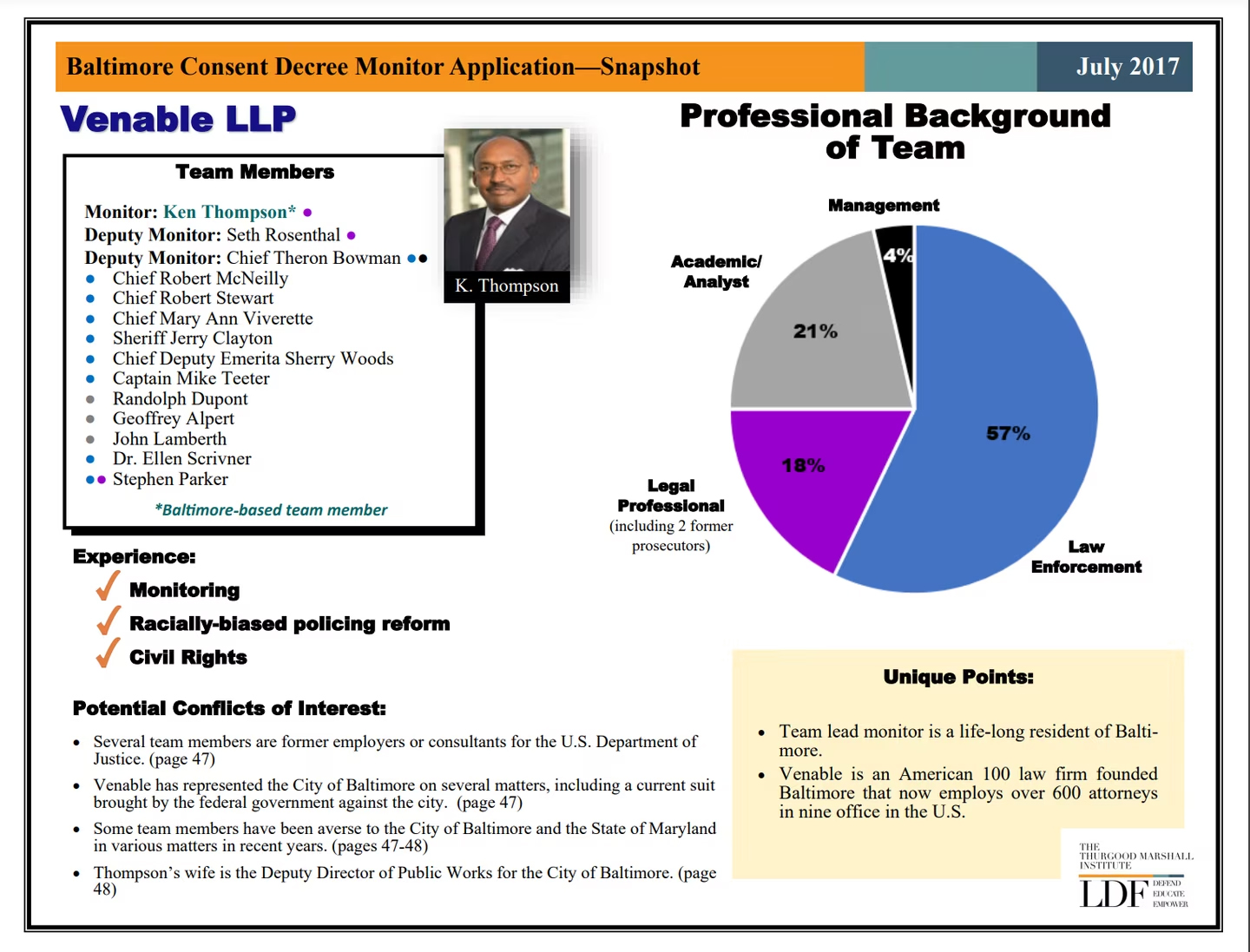

Though Ken Thompson and city officials saw the relationship as significant enough to disclose to the judge overseeing the decree, they never made it public. The move to appoint Ebony Thompson came five years after Venable LLP, her former employer and the largest law firm in Maryland, was chosen to lead the monitoring team. That decision was made despite community objections that the firm, a mainstay of Baltimore politics, would not be an impartial monitor because it had done legal work for the city.

Venable’s selection surprised community activists, and even insiders. Then-Mayor Catherine Pugh initially picked a different group for the role, but she was ultimately swayed by a last-minute push for Venable that was promoted by the federal judge overseeing the consent decree, according to an email reviewed by The Baltimore Banner and several people with direct knowledge of the selection process.

Venable did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In a cash-strapped city, monitoring the consent decree has come at a significant cost. Through January of this year, the monitoring team has billed the city nearly $8 million, with $1.3 million of that total billed to Venable by Ken Thompson.

Though it came to fruition several years later, the Thompsons’ relationship underscores those community concerns expressed in 2017 over the independence of Venable and its ties to City Hall. And, while city officials said the Thompsons’ relationship doesn’t violate their ethics codes, legal experts who study consent decrees found it odd and problematic.

“In a nutshell, I think it’s very unusual,” said Samuel Walker, an emeritus professor of criminal justice at the University of Nebraska Omaha who has long studied police consent decrees. “For a family relationship, the real question is the appearance. It’s the appearance of the kind of connection that could water down the implementation of consent decree reforms.”

A similar issue played out quite differently in New Orleans in 2013, when the U.S. Department of Justice argued that a federal judge should reject the mayor’s choice for its police department consent decree monitoring team, citing community concerns about political alliances. Eventually, the judge sided with DOJ attorneys and its preferred law firm was appointed.

Christy Lopez, who was one of those DOJ attorneys in New Orleans and now works as a professor at Georgetown Law, said the independence of the monitoring team is a critical component of any police consent decree.

Perceptions of close relationships, whether political or familial, have the potential to undermine the entire process in the eyes of the public, Lopez said. City officials, she added, should have recognized that when they appointed the younger Thompson as acting city solicitor.

“We need to get to a point where monitors and cities understand the importance of assuring the public as a whole of the integrity of the process, and understanding that that is as important as assuring the judge overseeing the consent decree that the process has integrity,” Lopez said. “The same level of concern and forthrightness should be part of the communication with the public, not just the judge.”

The city’s ethics codes state that someone should recuse themself due to a disqualifying relationship only for immediate relatives such as a spouse, parent, child or sibling. The Thompsons’ relationship “does not meet those requirements,” the mayor’s office said in a statement.

“Since Ms. Thompson became acting solicitor, all of the parties involved, including the mayor and the federal judge that the monitor reports to, have been well aware of the relationship between the acting solicitor and Mr. Thompson, and have expressed no concern whatsoever as to any conflict, whether real or perceived,” the statement said. “Acting Solicitor Thompson will continue to work with BPD, the DOJ and the monitoring team to finish the historic turnaround of the police department.”

Responding to questions from The Banner, Ken Thompson said Ebony Thompson is the granddaughter of his half-brother and that “such a relationship is too attenuated to have any legal significance under the applicable rules of conduct and does not create a conflict of interest.”

As for the selection of Venable, Ebony Thompson, the acting city solicitor, said in a statement that the firm had represented the city on “a number of matters” before being selected to lead the monitoring team, including representing the Department of Public Works in negotiations with the Environmental Protection Agency and other environmental matters. Though the law department did not provide a definitive list of the legal work Venable had done for the city, it said “there has never been any conflict with respect to the important oversight work of the Department of Justice or any other work related to the decree.”

To construct Baltimore’s “hybrid” monitoring team, Ken Thompson of Venable was joined by members of other contending groups, namely Exiger LLP and 21st Century Policing, which were well stocked with consultants who had expertise on police practices.

The origin of Venable’s fusion into that team remains murky and is not fully articulated in public records. U.S. Judge James K. Bredar, who oversees the consent decree, took credit in court filings for the idea of combining two teams, but specifically stated he did not dictate which teams should be chosen. Bredar declined to answer questions for this article.

But Andre Davis, who was city solicitor when Venable was elevated to the position, said the push for Venable did not come from the law department. He described it as an “iterative process that involved the law department, the DOJ, and most importantly of all, the federal court.”

“We had ideas; the DOJ had ideas,” Davis said.

He added, referring to Bredar: “The most important ideas were the federal court’s ideas.”

Closed-door meetings and Venable’s comeback

The tangled relationships of Baltimore’s police consent decree were a concern from the beginning.

In the summer of 2017, city officials held town halls to solicit community feedback on selecting an “independent monitoring team” that would impartially observe the agency’s progress and submit detailed reports to the judge.

At the town halls, advocates bristled at Venable’s political ties to City Hall, said Ray Kelly, a longtime police reform advocate who helped the DOJ with its Baltimore investigation.

Community activist group Baltimore Action Legal Team formally quizzed Venable over its ties to the city during the selection process. In a recent email, BALT said it never received a response from Venable.

Venable is one of the city’s most prolific law firms, having done work for an array of clients, including The Baltimore Banner. And the firm’s political connections in Baltimore are notable.

Jim Shea, the former managing partner of the law firm, ran for governor with Scott, the current Baltimore mayor, as his running mate. He then served as Scott’s first city solicitor, before his protege Ebony Thompson took over.

Ken Thompson served on the transition teams for former mayors Stephanie Rawlings-Blake and Pugh. Two relatives of former Baltimore Mayor Martin O’Malley work at the firm. Ralph S. Tyler, who was the Baltimore city solicitor from 2004 to 2007, joined Venable in 2011.

Though Venable’s candidacy for monitor was met with blowback, community members rallied behind two other teams: one led by a notable civil rights attorney, Susan Burke, and another led by former Maryland State Police trooper and FBI agent Tyrone Powers, who had also served on Pugh’s transition team.

Soon after the town halls, the finalists had been chosen – and Venable was not a front-runner, according to people who participated in the selection process. And yet, for reasons not articulated in public records, the law firm was brought back into the fray.

“They went behind closed doors and decided,” Kelly said. “We didn’t get to select a monitoring team. … We knew that the powers that be put Venable in that place, whoever those powers were back then.”

Kelly is not the only one close to the selection process who suspected that a closed-door meeting revived Venable’s bid to be monitor.

Sen. Jill Carter, a Baltimore Democrat who was the head of the city’s Office of Equity and Civil Rights at the time, said that then-mayor Pugh had decided to back Powers. But sometime after that there was a telephone conference involving the DOJ, the city solicitor’s office, the police department and Bredar, Carter said.

Carter said she didn’t know what was discussed during the meeting, which she did not attend, but that the decision to appoint the hybrid team came shortly after.

Having participated in several discussions about the consent decree with the law department and the police department back then, Carter noted their defensiveness when it came to discussing the DOJ findings. She suspects the selection process was skewed from the beginning.

“The fix was always in,” Carter said.

There is no record in the court docket of a telephone conference. Bredar’s office declined to fulfill a records request for a calendar entry that might have documented it, citing its exemption from federal public records law. The city solicitor’s office has not provided records of any calendar entries noting the meeting. The Banner first requested those records in mid-April.

Bredar similarly declined to answer questions about the selection process, with a spokesperson saying a judge’s role is to comment only on matters brought before the court.

In an interview, Powers, the runner-up, said the selection process was “corrupted.” He recalled being told by Pugh that he was her preferred candidate, but that “there were some other forces that changed my decision.”

“That’s how she said it to me directly,” Powers said. “No embellishment, no enhancement.”

The Banner’s attempts to reach Pugh were unsuccessful.

Though Powers had won over the mayor, he appeared to be outfoxed by other power players in city government. Looking back to 2017, Powers said he came to the conclusion that city leaders and Bredar made their decision “based on relationships rather than based on effectiveness, and we couldn’t compete with that.”

Shortly before the announcement of the monitoring team, Davis, the city solicitor, sent Powers an email, saying the parties had “followed the judge’s lead” in assembling the monitoring team.

“As an aside, I also want to alert you to the fact that, as you well know, you have many vocal supporters in the Baltimore community. That significant support speaks highly of your reputation in the city,” Davis wrote. ”Some of the rumbling I have heard, however, has seemed to convert support for you into opposition to the city’s efforts. This is regrettable. I know that it is not what you hope for.”

The city solicitor asked Powers to issue a statement of support for the monitoring team and express a “positive outlook for the city’s likely success in striving to achieve reform.”

Powers declined to do so.

Bredar celebrated the appointment of the hybrid monitoring team in a court order but did not take credit for it outright. Instead, he emphasized his deference to the “involved parties,” i.e., city leadership and the DOJ.

Unlike in New Orleans, the DOJ made no public argument against the selection of Venable, despite its connections to City Hall. In fact, led by then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions, the DOJ was uninterested in moving forward with the consent decree at all, according to court records and media reports.

In April that year, just days after Sessions instructed the DOJ to review all police consent decrees, the DOJ asked for a 30-day delay, expressing “grave concerns” whether federal involvement was necessary. Residents of the city, meanwhile, pushed back forcefully against the proposed delay.

A spokesperson for the DOJ declined to comment on the selection process or the relationship between the Thompsons.

The ‘narrowly constrained role’ of the public

In court filings, Bredar acknowledged the concerns raised by citizens of Baltimore on the selection of the monitoring team by describing the “narrowly constrained role that the public has been afforded in the parties’ dispute.”

But over the years what was once a fervor from citizens over the consent decree has all but dried up.

In a Baltimore courtroom in January, DOJ attorney Tim Mygatt seemed to concede that, at their core, police-community relations hadn’t changed as much as federal officials had hoped they would.

Responding to a line of questioning from Bredar about how attitudes have changed toward the Baltimore Police Department at the neighborhood level, Mygatt said, “I think the short answer to that, your honor, is, not as much as we would like to see.

“People continue to say, ‘We don’t see it yet. We don’t feel it yet,’” Mygatt said.

For criminal justice reformers, part of the blame for the evaporated enthusiasm lies with the monitoring team.

Members of the team are rarely if ever seen walking the streets of Baltimore, said Powers, the runner-up. And Kelly, the police reform advocate who was once a member of the monitoring team as a community liaison, said he was often the only one arguing for more community involvement.

“I wasn’t just going to represent the community voice in the court proceedings,” Kelly said. “I wanted to actually make sure that the community was getting educated and informed, so a lot of what you saw me do as an organizer didn’t happen before I got there.”

Covering the Baltimore Police Department consent decree

As the police department enters its seventh year under federal oversight, the monitoring team has solicited community feedback on a large scale only once: in the form of a survey with Morgan State University released in early 2020.

Polling the residents returned dismal results: 3 out of 5 participants said they were dissatisfied with policing in Baltimore, and nearly half of those polled said they feel nervous when they see a Baltimore Police Department officer or cruiser.

The monitoring team hasn’t released another poll, though it indicated in a monthly statement last year that it is in talks with the university to do another round of surveys in the near future.

Although the police department has made considerable progress on training and policies, several of the prescribed reforms are yet to be implemented in practice, a shortcoming that department leaders attribute to low staffing levels.

That led Bredar to call recruitment and staffing the single biggest impediment keeping the department from exiting the decree.

Police reform advocates, meanwhile, have grown increasingly frustrated with the way Bredar has handled the consent decree. They cite a relentless focus on staffing levels and the collegial environment of the consent decree’s quarterly court hearings.

Heather Warnken, executive director of the Center for Criminal Justice Reform at the University of Baltimore School of Law, said the focus on staffing ignores that Baltimore spends among the most per resident on policing of any major U.S. city.

“It hides the ball from the far more important questions,” Warnken said.

Aside from the moment of candor from Mygatt, the DOJ attorney, in January, community attitudes around police are rarely the centerpiece of discussion in the court hearings. But Warnken said that is the metric that matters most.

“If we act like that’s peripheral to the consent decree,” she said, “we’re blowing it.”

Learn more about our analysis, reproduce our findings and download an electronic copy of the consent decree billing database by visiting our GitHub page.

Data reporter Ryan Little and reporter Adam Willis contributed to this report.