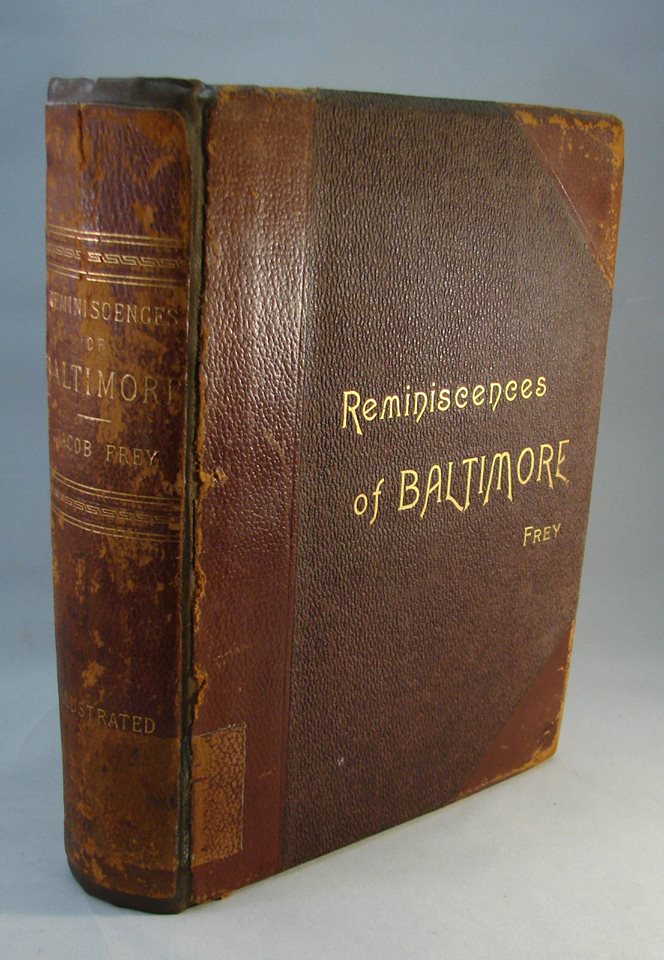

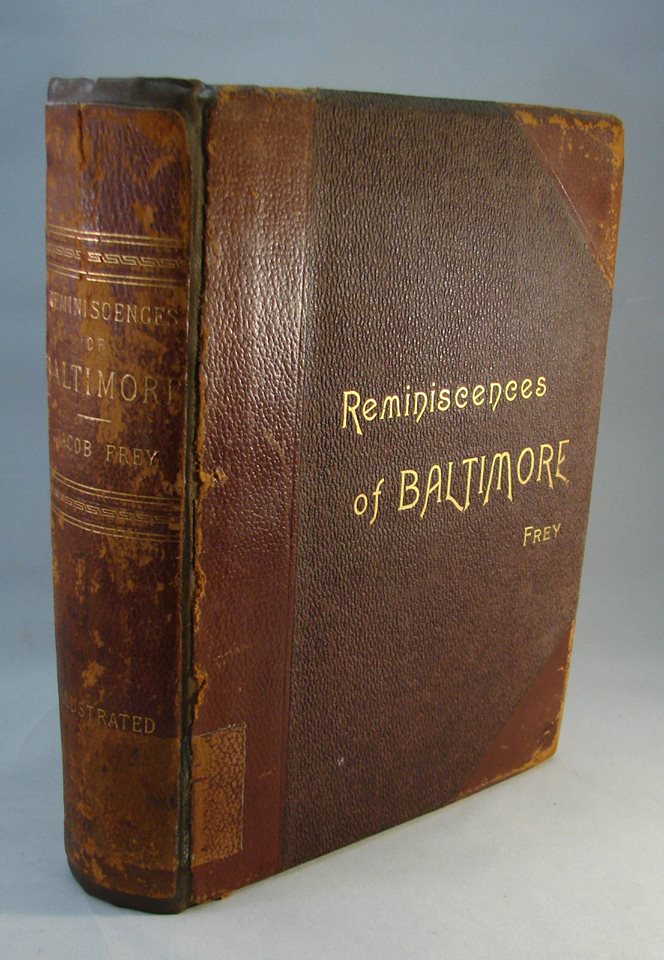

Marshal Jacob Frey

An incident that brought out the abilities of the Baltimore police force, was received during the railroad riots of July 1877. Abilities making Baltimore’s Police shine. Monday, 16, July 1877, the Firemen of B&O Railroad’s freight engine team left their jobs. It was a time when the people of this city had lost their heads when the policemen in Baltimore… and Deputy-Marshal Jacob Frey in particular, remained cool, they were brave, and they were strong-minded. A strike was brought about by the Firemen of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad’s freight engine team… a strike that was brought about, after a 10% reduction was taken from their wage. These men demanded that well before the cuts, they were working at a pauper’s wage, but that with the cuts, they could not afford to live the life of a vagrant. The Railroad, however, declared that a downward spiral in the overall business interests of the country had compelled the pay cuts, and made them unable to pay a higher wage.

There were about one hundred of them at first. In many instances, they went out on their trains a few miles from the city, and when the engines stopped to take coal they left their places, refusing to go any further. At first, the strike seemed easy to manage, but as the first day wore on, and news came that the trouble had reached Martinsburg, further that the militia had been called out, things became more serious. The police were promptly on hand. They were stationed in twos and threes, at various points between Baltimore, the Relay House, and a squad of twelve that were at Camden Junction.

Like many times of tension in the city of Baltimore, both before this riot, and in many riots since; the first day passed rather quietly, although in this case few of the freight trains left the city. On the second day, however, 17 July 1877, [Tuesday] the excitement began. A freight train of eighteen loaded cars from the West; bound for Locust Point, was partly wrecked by means of a misplaced switch at a trestle near the foot of Leaden Hall Street, Spring Garden, the engine and several cars were thrown into a gulley. News, arrived of a fight at Martinsburg, in which two firemen were shot. At 1st 1ight the employees of the Baltimore and Ohio Company held a meeting, they decided to support the strikers, but first, they would try seeking conciliation with the company.

The conciliation failed, and the strike went on. It was Wednesday, [18 July 1877] the third day of troubles for B&O, the West Virginia authorities called on President Hayes for troops, and a proclamation was issued at once by the President. Troops were promptly sent. Of course, all this had its effect in Baltimore, but on that day there were no hostile demonstrations here. The freight business amounted practically to nothing, but the passenger trains arrived and departed as usual.

The Company decided not to recede from its position, and a reward of $500 was offered by it for the arrest of the person, or persons who caused the Spring Garden wreck. On the fourth day [19, July 1877] the troubles continued in Martinsburg, but there was no outbreak here in Baltimore. It would take nearly a full five days for any excitement to take place here. But when it arrived, Baltimore was more excited than it had been since the war.

About 3 o'clock in the afternoon of Friday, when the news had been received that the strike at Cumberland threatened to assume general proportions, Governor Carroll held a consultation with the officers of the Baltimore and Ohio Company, and became convinced that the presence of the military at Cumberland was necessary for the preservation of peace and order. A half-hour later he issued an order to Brigader-General Herbert, commanding the First Brigade, M. N. G., ordering him to proceed to Cumberland. Simultaneously he issued a proclamation calling upon the rioters to desist. Soon afterward General Herbert held another consultation with Governor Carroll to consider whether the military should be summoned to their respective armories by a "military call" from the bells. Governor Carroll objected to this, and General Herbert tried to get the men at the armories by the ordinary means, but not succeeding very well, again asked the Governor that the bells be rung. This was done, and a great misfortune was proven.

At twenty minutes to 6:00 the call 1-5-1 was sound from the fire bells at City Hall. The people knew what it meant, and in a very short time, the streets around the armories were filled with men and boys of all ages who sympathized with the strikers. It was about the time that the work in the factories was over, and all the workmen helped to swell the crowds. In front of the armory of the Sixth Regiment, at Fayette and Front streets, the mob numbered at least 2,000. Strangely enough, the officers of the regiment sent word to the police headquarters, asking that policemen be sent to clear the way so that the regiment could march on to Camden station.

The old system then in vogue scattered the policemen, so that not enough of them could be collected in time for the work, and in two hours the crowd was so large that no force was able to handle it.

The troubles at the Sixth Regiment Armory began at about seven o'clock. A brickbat was thrown into one of the windows.

Four policemen, Officers Albert Whitely, James Jamison, Oliver Kenly, and Roberts-were stationed at the door, and in spite of the volleys of stones, missiles, and jeers that followed they manfully stood their dangerous guard, although the four militiamen who had been with the policemen had been called in. The hour set for marching was 8.15 o'clock, and the crowd had become maddened and aggressive. The companies, however, destemmed to pass the rioters. When they appeared on the street there was a riot so general that it drove the men back again into the building. 'the next time they came out they had orders to fire. The first company fired high, but the attack became so heavy on the following companies that they discharged their weapons into the crowd. From that instant all along the march to Camden station the firing was continuous and general, resulting in the killing of about a dozen people and the serious wounding of much more.

The Fifth regiment did not use its guns, although it was severely attacked and had every provocation to fire. The men marched admirably through showers of stones and other missiles. There were 250 of them. At the junction of Camden and Eutaw streets, a solid mass of rough-looking men blocked their passage. They came to a halt for a moment, and although the bricks were falling fast, Captain Zollinger counseled his men NOT to fire.

Then he ordered them to prepare to double-quick with their fixed bayonets into the depot. Drawing his sword, Captain Zollinger shouted to the mob to give way that the command might pass. A brawny man opposed the Captain, who promptly knocked him down, and amid the hoots and yells, came several shots from the

Crowd; inviting the regiment to charge the depot. Soon after the regiment had reached the station the building was set on fire, the rioters attempted to interfere with the firemen, but fortunately, their attempts had failed, and the flames were knocked to embers, and then to ashes.

The fearless service of the police during these rebel rousing times has never been properly recognized bar a few brief passages in the newspapers. In every instance, they awed the mob, while the soldiers exasperated the situation.

One policeman was equal to a dozen soldiers. Until long after midnight the police protected the military and guarded all the depot buildings. It was our police who protected the firemen, their engines, and the hoses they used, and therefore it was our police who saved the buildings. They were fired upon by the mob, and some were wounded, but they wounded a number of the mob in return, and in addition, they made many arrests.

The result of this great excitement was that the order sending the soldiers to Cumberland was withdrawn, and a proclamation to that effect was issued by Mayor Latrobe.

During these days the efficiency of the police department was tested and proven. Deputy-Marshal Jacob Frey had command of, and around Camden station. While for nearly seventy hours he went without sleep, as he single-handedly maintained control of the mob. Long before any of his officers could assemble, on that Friday and previous to the arrival of the military, Frey had cleared the platform, and front pavement of several hundred excited, and unruly men. But, when reinforcements arrived, and without hesitation, Deputy-Marshal Frey waded into that crowd, where he in short order arrested two of the agitators. Without incident, they were taken into his custody and transported to the Southern District Station House where Frey himself, booked the pair.

On Saturday night crowds again collected around Camden station. About 9 P. M. a fire-alarm excited the rioters so that they rushed towards the lines that the police had formed. Shots were fired by the rioters, and 'several officers fell wounded. Then it was that Deputy-Marshal Frey told the men to keep steady, and a moment afterward, their pistols being drawn, the command of "Take AIm, Fire" was given. They fired low, and as they fired they rushed forward, and each officer grabbed a prisoner. Fifty arrests were made; several men were killed and a. number wounded. There was another outbreak at 11 o'clock and fifty-three more arrests were made. On Sunday morning large crowds again collected around the Camden Station, and they were closely pressing upon the picket lines of the Fifth Regiment. Deputy-Marshal Frey, not liking the looks of things, sent for a squad of twenty policemen. When they arrived the Deputy-Marshal took charge of them in person. He told the crowd that he was going to "clear that street" and he advised all peaceably disposed of persons to go home. Many of them did so but much more remained. Turning to his men, the Marshal gave orders to " Forward," and in a very short time, the rioters were driven away. They knew the Deputy-Marshal, and they were afraid of him.

When the riot had assumed such threatening proportions every effort was made to protect the city. United States soldiers from New York and other cities were promptly ordered to Baltimore. General W. S. Hancock arrived with eight companies of troops from New York harbor, and two war vessels with 560 men, fully equipped, anchored in the Patapsco. Several hundred special policemen were sworn in by the Police Board. Among them were such well-known citizens as William M. Pegram, Alexander M. Green, C. Morton Stewart, Frank Frick, E. Wyatt Blanchard, James H. Barney, J. L. Hoffman, Robert G. Hoffman, W. Gilmore Hoffman, John Donnell Smith, William A. Fisher, Frederick von Kapff, and Washington B. Hanson. They were supplied with the regular badges, and they did good work. The regular policemen were unfaltering in their duty, and most of them did not sleep during the more than fifty hours. The great show of strength by the police and troops overawed the rioters, and the troubles were gradually quieted. The following Saturday freight trains, each guarded by ten soldiers, moved out on the road.

The strikes in other cities continued, more or less, but within two weeks they were over. Trouble on the Northern Central railroad was happily averted. The jury of the inquest which sat upon the man killed by the Sixth Regiment was very thorough in its investigations, and after several days consumed in taking testimony, it rendered a verdict which found the rioters guilty of the troubles but charged the regiment with shooting too hastily and too indiscriminately. It found fault because there were not more policemen on hand around the armory. This, however, was purely the fault of the military authorities in not giving sufficient notice to the Marshal. The part that the police force took in the memorable conflict will forever stand a monument to its courage and efficiency.

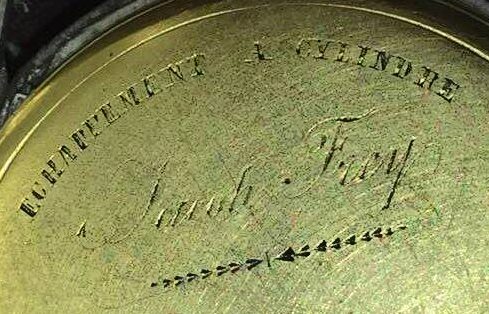

Jacob Frey's Watch

Union Soldiers Attacked

The first months of the civil war were a time sore trial for Baltimore’s police, in a border city of strong Southern sympathy they had the tough job of protecting union soldiers passing through, won their way to the southern battlefields, the soldiers, unlike other passengers were carried slowly to the streets in the course cars. The billing crowds, cheering Jefferson Davis, saw the wrapper tape to attack and they did a show in the true riding tradition of all Baltimore. They threw stones and other missiles at the cars. But on April 19, 1861, the crowds attempted to stop the soldier’s movement and it was a fateful day for the Baltimore police department. Tamales blocked the track near Gay and Pratt streets by piling on it a dray load of sand, a pile of cobblestones and some light anchors.

Police Heads Imprisoned

220 union soldiers got out and attempted to march to Camden station. It was the signal for the onslaught. The rioters attempted to snatch soldier’s rifles during the ensuing fight. Police with pistols drawn, threatening to shoot tried to protect the Union soldiers, but to little avail. Four soldiers were killed, 36 wounded. Likewise, 12 citizens were killed. Some weeks later General Banks in command of the Union forces in Baltimore, decided to take over the police department. He arrested Marshal Kane and confined him to Fort McHenry. In the later, hours he arrested the final three commissioners. They were sent to prison where they were held for more than a year. New Commissioners were selected and those with Union sympathy were named in the new department and went on the Federal payroll. In the posts war, the department began innovations that have since become the trademarks of American police everywhere. Among other things, the patrol wagon, the helmet, and the police telegraph box were introduced. Up to about 1885 again necessary for policemen to Carey very drunk prisoners on their backs to the station house that is when they commandeer a wheelbarrow. Chicago was the first American City to employ patrols and Baltimore is believed to be the second. While in the gymnasium of Central's station reading an illustrated magazine Deputy Marshal Jacob Frey saw facts on police patrol wagons first being used in Chicago. He brought the idea before the (BOC) Board of Commissioners; they were mildly interested. Frey didn't give up on ideas that he believed in; some weeks later he called the board’s attention to the matter again, they had forgotten about it but promised to look into it. Wagon's and the Police Telegraph Box Systems were the future of policing in Frey's eyes,

Telegraph Box System

After the BOC failed to act, Deputy Marshal Frey took matters into its own hands. He sent members of the department to Chicago to see how the "New Fanged" patrols wagons worked. An old record states, "they were charmed." While there, they also looked into Chicago’s new "Police Telegraph Box" system. (the Call Box). The results of Baltimore's trip was both of these tools were in Baltimore by the fall of 1885. According to Baltimore Sun paper reports, Chicago was the first to use the Police Telegraph System, and Baltimore became the second Department in the country to use the system. Baltimore continued using these boxes from 1885 until 1986 when they established a 1-800 number for police to use when radio use was inappropriate. All boxes were finally removed from service by 1988.

The Police Helmet

Already worn in other cities, was made of a rule in Baltimore and 1886. It was introduced by Commissioner Alford J. Carr. It took the place of the derby formerly worn by policemen. Commissioner Carr specified that the helmet the black in the winter and pearl gray and summer. The helmet at that time was significant of rank, I only patrolman and sergeants and wore it. The marshal and his deputy and captains and lieutenants were. It was said at the time that the hygienic the fact of the home and was excellent, giving the policemen’s had a chance to secure proper ventilation.

Friday, Aug 20, 1886, New Badge

New badges for the police captains – today the captains of the police force of the city will appear with new badges. The police board having issued an order to that effect. For some time past, Marshall Frey states, the captains have complained that their old badges were identical with the badges worn by nearly every private detective or watchman in the city. The old badges were simply a star within a circle, with the words “Capt. of Police” on the rim. The new badges are much more elaborate and are very handsome. The form is a shield, about 2 ½ inches long and 2 inches wide. Of silver. The Maryland Coat of Arms is and blazoned on the face. An “eye” is engraved over the coat of arms. The word “Capt.” appears below. The new badges were made by Mr. John W. Torsch. Marshall Fray says that the force is a state institution, he thought it appropriate to have placed the Maryland coat of arms upon the badge. He further says that the “eye” is intended to remind the captains that their duty is to be always on the alert.

Jacob Frey served as Marshal from Oct 15, 1885 - Jul 12, 1897

On July 12, 1897, the active connection of Marshal Jacob Frey with the Police Department ceased. On October 7, 1897, Capt. Samuel T. Hamilton was elected Marshal of Police to succeed Marshal Frey. Marshal Hamilton was a veteran officer of the Civil War and a man of indisputable courage and integrity. For many years following the great civil conflict he had served on the Western frontier and took part in the unremitting campaigns against the Sioux and other Indian tribes, who were constantly waging war upon the settlers and pioneers as they pushed their way toward the setting sun, building towns and railroads and trying to conquer the wilderness and its natural dwellers. In the Sioux campaign of 1876, when Gen. George A. Custer and his gallant command, outnumbered ten to one by the Indians in the valley of the Little Big Horn, were annihilated, Captain Hamilton and his troop rode day and night in a vain effort to re-enforce Custer and his sorely pressed men. It was on June 26, 1876, the Seventh United States Cavalry rode and fought to their deaths, and on June 27, the day following, the reinforcements arrived, exhausted from their terrific ride across the country. Captain Hamilton and his troop fought through the rest of the campaign, which resulted in Sitting Bull, the great Indian war chief, being driven across the Canadian frontier.

The Harbor Thieves

The Sun (1837-1987); Jul 27, 1886; pg. 4

The police have not yet arrested the thieves who robbed several vessels early Sunday morning in the harbor. The thieves are supposed to be the same who robbed one vessel in Washington last Friday night. Robberies have been reported all along the coast. And the police have good cause for believing that a band of professional thieves are doing the work as a great deal of adroitness and system have been shown. In speaking of the need for better facilities for capturing the thieves, police Marshall Frey said he had made a written recommendation on the subject to the board of police commissioners, as follows;“ There exist a necessity for a harbor police boat, as many depredations and other offenses are committed on vessels and along the shore by persons in small boats, the policeman on land in many instances being unable to see or hear them, and in many cases when seen or heard the thieves are enabled to escape for the want of proper facilities to pursue and arrest them. About 18 years ago we had yawl boat doing duty about the harbor and it did good service, but the demands for the policemen on land compelled us to abandon even that crude system of harbor protection.” The police board recognized the importance of this recommendation and incorporated a provision in an act to better define the special fund in the hands of the board so as to provide for a harbor patrol boat, but the provision was stricken out when the act was passed by the last legislature. The special fund is raised by fines imposed by the police magistrates and is used in building station houses, for patrol wagons and pensions. The Marshal says that New York, Philadelphia, Boston and other cities have harbor police boats, which are a great help in protecting vessels property, he says that the Baltimore needs a steam yacht, with about four rowboats. The yacht could move up and down the harbor all night long, and the rowboats could patrol the docs under the direction of the yacht, which should have its regular police captain. He thinks it would require about 15 or 16 additional policemen to do the work thoroughly. The Marshal said also that the people of the city have no idea how many thefts are committed in the harbor. The only vessel Robberies usually reported in the newspapers are those of jewelry, clothes, and money, but by far the largest loss is in Produce, which is stolen so successfully that the captain of the vessels and the owners of the products are not aware of the robbery until the Produce is taken out and a shortage discovered. It was too put a stop to these robberies, as well as to catch the professional thieves, that the Marshal recommended the establishment of the harbor police boat. Mr. George Colton president of the board says that he does not think the board could establish the harbor system without special legislation. The board, as well as the Marshal and Deputy Marshal, recognize the necessity for a patrol boat.

Guarding The Harbor

Reported for the Baltimore Sun

The Sun (1837-1987); Jul 31, 1886; - pg. 6

Policemen in rowboats on the lookout proceeds – the patrol wagons. Marshall Frey, acting under instruction from the police board, has organized a special system of police protection for the harbor of Baltimore. He has four flat bottomed boats and 12 policemen now engaged in the work. Three policemen are assigned to each boat, and each boat will carry two pairs of oars so that in the case of a chase two men can pull. Each boat will also be provided with a dark lantern. The policeman selected to do this duty have been chosen from those who are best acquainted with the harbor and its immediate surroundings. Of the four boats, to have been assigned to the Eastern District, one to the central and one to the southern district. The boats will start out at dark and remain on duty until daylight.

Pres. Colton, of the police board, says that this experiment was started as the best thing the board could do under the circumstances. In the absence of necessary legislation upon the subject. The board could not place a regular steam patrol boat in service. At the last session of the legislature, he had asked for a police boat, but the legislature would not consent. The present experiment will cost but little, as the boats are hired by the night at a small cost. There is a reason to believe that it will prove successful.

Marshall Frey is speaking of police protection to the harbor, said a steam launch was undoubtedly the best means of guarding the harbor. He could not definitely state what kind of boat would actually be the best, but his impression was that a boat should be built with all the conveniences necessary for the service. He thought that about 25 men would be a fair compliment. The present experiment would he said be a great move in the direction of harbor protection, and that nothing better could be done until the next meeting of the legislature when the request for a police boat will be repeated.

The arrangements for the introduction of patrol wagon system are nearly completed: all of the polls have been placed in positions and the wires run. The boxes will probably be placed in position next week the new wagon for the southern district is finished. It was built by Mr. John F. Bunter, of Baltimore. It is somewhat similar to the wagon used in the Central District but has several improvements. The body of the wagon is 7 feet long. To the left is a small apartment for the stretcher, was can be placed in without the slightest difficulty. A similar apartment on the right can be used for placing heavy weapons in case of an emergency. The entrance is by steps in the rear. The steps are all finished and brass. The body of the wagon is painted black. The wheels are Carmine with yellow borderings. The wagon will be drawn by one horse. The work of interest in seeing the system in the Eastern District is also making rapid progress.

The Harbor Patrol

Reported for the Baltimore Sun - The Sun (1837-1987); Aug 7, 1886; -pg. 6

A trip in one of the police boats – sites revealed by the dark lantern. “Where’s Your Light?” The words were followed by a flash of the dark lantern which made a halo of bright in circles the head of a colored man who was scuttling a boat at night toward a fleet of Bay vessels lying ahead to the wind of Henderson’s wharf.

“Boss, I just took somebody the shore,” and the orbits of the surprised fellow in large as he winked and blanked in terror of the unseen questioner. The man shaded his eyes tried to pierce the glare of the lantern but every moment was followed by the blinding light before him.

A quick flash in the light was cut off, revealing to the scared man three policemen in one of the harbor patrol boats of the Eastern District. In the Stearns, sheets set a Sun reporter, who was temporarily coxswain of the swift little cutter. After instructing the Charon of the reason he was challenged he was permitted to go and was a happy man.

A cruise with a harbor patrol is an interesting feature in that branch of police work recently inaugurated by Marshall Frey for the protection of property on wharves and on shipboard. Therefore boats on duty nightly, each containing three officers, who have been selected on account of previous acquaintances with the harbor and their knowledge of handling boats. The work is divided into four boats. Beginning at the southern extremity of the Light Street Wharf the central crew patrols along with the Steamboat peers: thence onto the north side of the basin to the drawbridge. Commencing there, number one crew, of the Eastern District patrols to Henderson’s wharf, where number two crew picks up the work and extends it to the Lazaretto light. Capt. Delanty’s crew and the southern district have the south side of the harbor, including the shipyards, coal wharves and steamship piers as far as Fort McHenry.

Capt. Auid, with foresight born of experience with ships and boats, selected two handsome cutters which formally were one Mr. T. Harrison Garrett’s yacht Gleam. They are particularly adapted for the work, being light and easily driven through the water. Two officers pull while third attends the filler, bundles the light or give directions. A system of order and regularity is in force. Each man is assigned to some detail of the boat or his charge of some of the gear so that no confusion can occur.

On the night in question there was a strong southerly breeze, which made the harbor a little lumpy, causing the motion of the patrol boat that guards the Canton hallow to leap and jump over the waves as it delighted with the change from the smooth water that prevailed under the ice of wharves and ships further up.

Strong and sturdy polls made the cut or skim over the water like a recent shell. The unexpected incidents during the trip were in some cases very ludicrous. Suddenly pounding the stern of the vessel, a wharf came in for inspection. The dark lantern soon showed that the officer in the bow was on the alert, and on lighting up the wharf with the lantern two lovers were on graciously surprised. The head that rested on Romeo’s shoulder became erect abruptly as if it never knew any other position, and Romeo himself appeared very much confused. All was darkness again in the boat and on the wharf as the light of the lantern were set off, and maybe the old, old story was whispered once more under the inspection of the waves that gurgled beneath the pier.

Past lonely wharves and warehouses, where everything was quiet: under Stern of great ships loading for C; nearly grazing the head while passing under the bow of some small craft: then up and obscured dock, peering under peers: then darting after a boat with a lone occupant to learn his business: past steamers banks and ships, factories and furnaces, and then under the glare of the two red lights of the Lazaretto, which marks the bounds of the police patrol, the little boat silently, swiftly collided.

In the distance, the lights of the city twinkled and the street showed their outlines by the regularity of the gas lamps, which appeared like a Torchlight procession. The only noise on the water was the swishing of the waves against the seawall, or the pool – pool of some belated tug returning to point. Occasionally the crew rested on their oars and drifted with the current, or stopped to scan an object that looks like a boat.

The duties of the patrol are multifarious. Vessels are boarded, and those on board instructed on the necessity of keeping doors locked and look out on property lying about decks. Every rowboat or sailboat is now known by the patrol. They know to whom it belongs and where it ties up. His absence suggests inquiry, and its whereabouts are determined. The route of the patrol is governed by circumstance, but with and every hour the whole beat is twice covered. Preliminarily to the general cruising, vessels which arrived during the day are located and made aware of my duty of keeping a lookout.

An illustration of the carelessness of master of the vessel was given the other night. A light was seen through the open door of a schooner cabin and rather an unreasonable hour. The patrol went alongside and halted the vessel. No one responded for several minutes, and then not until the oars had been used in a knock against the cabin a man came quickly up the companionway rubbing the sleep from his eyes. He was told of the probability of seeds being invited to call upon him, and as a precaution, he closed his cabin. “If all Mariners sleep like that fellow and his crew,” said the officer, “chloroform need not be used.”

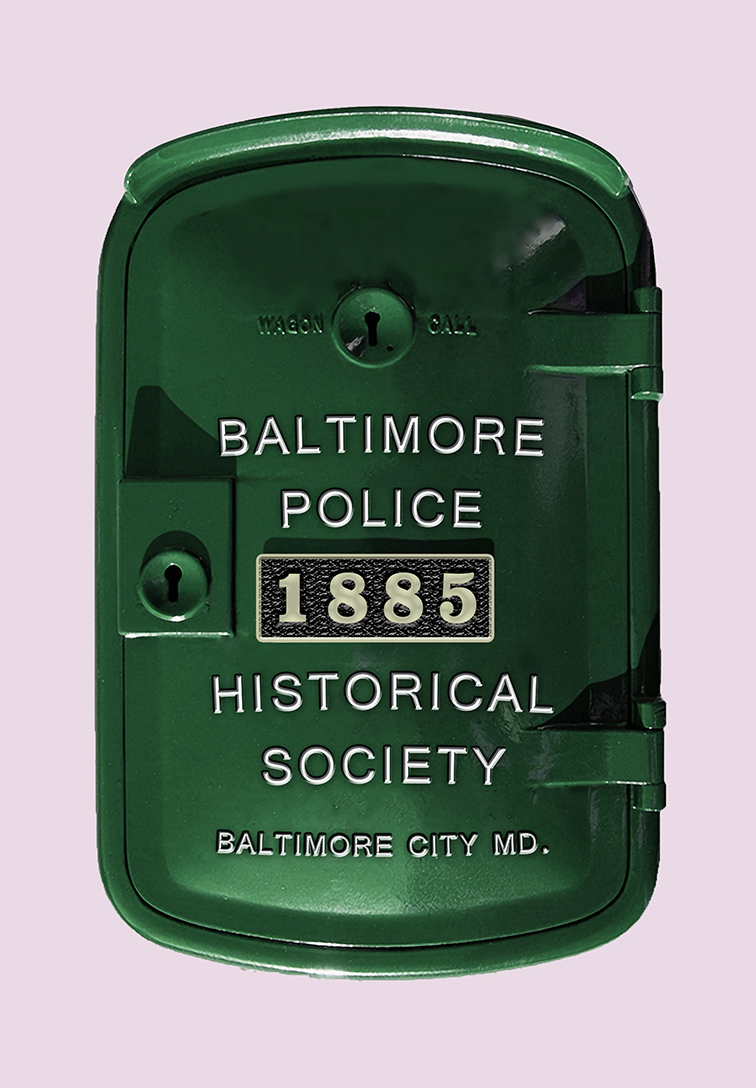

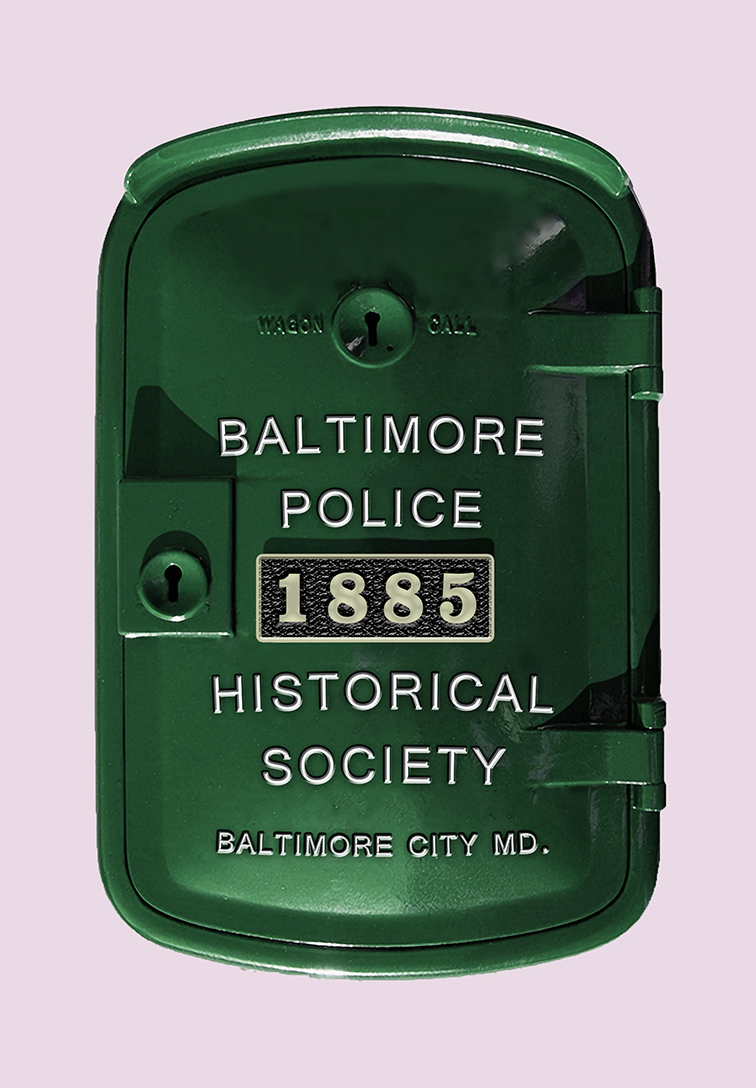

Police Call Box

Saturday (16 October 1885) Box 63 was the 1st used

It was located at the corner of Franklin and Charles Streets

History

Based on the following Baltimore got its first Call Box in 1885

Baltimore's first patrol wagon went into service on 25 October 1885 and is believed to have made Baltimore only the second city to use patrol wagons in the country behind Chicago. While in the gymnasium of Central's station reading an illustrated magazine Marshal Jacob Frey saw facts on police patrol wagons first being used in Chicago. He brought the idea before the (BOC) Board of Commissioners; they were mildly interested. Frey didn't give up on ideas that he believed in; some weeks later he called the board’s attention to the matter again, they had forgotten about it but promised to look into it. Wagon's and the Police Telegraph Box Systems were the future of policing in Frey's eyes, and after The BOC failed to act, Marshal Frey took matters into its own hands. He sent one of the members of the department to Chicago to see how the "New Fanged" patrols wagons worked. An old record states, "they were charmed." While there, they saw Chicago’s new "Police Telegraph Box" system. (Known now as the Call Box). The results of Baltimore's trip was both of these tools were in Baltimore by the fall of 1885. According to Baltimore Sun paper reports, Chicago was the first to use the Police Telegraph System, and Baltimore became the second department in the country to use the system. Baltimore continued using these boxes from 1885 until 1985 when they established a 1-800 number for police to use to call back into the station when radio use was inappropriate. All boxes were finally removed from service by 1987.

An 1894 advertisement for the "Glasgow Style Police Signal Box System", sold by the National Telephone Company. The first police telephone was installed in Albany, New York in 1877, one year after Alexander Graham Bell invented the device. Call boxes for use by both police and members of the public were first installed in Washington, DC in 1883; Chicago and Detroit installed police call boxes in 1884, and in 1885 Boston followed suit. These were direct line telephones placed on a post which could often be accessed by a key or breaking a glass panel. In Chicago, the telephones were restricted to police use, but the boxes also contained a dial mechanism which members of the public could use to signal different types of alarms: there were eleven signals, including "Police Wagon Required", "Thieves", "Forgers", "Murder", "Accident", "Fire" and "Drunkard".

The first public police telephones in Britain were introduced in Glasgow in 1891. These tall, hexagonal, cast-iron boxes were painted red and had large gas lanterns fixed to the roof, as well as a mechanism which enabled the central police station to light the lanterns as signals to police officers in the vicinity to call the station for instructions.

Rectangular, wooden police boxes were introduced in Sunderland in 1923, and Newcastle in 1925. The Metropolitan Police (Met) introduced police boxes throughout London between 1928 and 1937, and the design that later became the most well-known was created for the Met by Gilbert MacKenzie Trench in 1929.[6][7] Although some sources (e.g.) assert that the earliest boxes were made of wood, the original MacKenzie Trench blueprints indicate that the material for the shell of the box is "concrete" with only the door being made of wood (specifically, "teak"). Officers complained that the concrete boxes were extremely cold. For use by the officers, the interiors of the boxes normally contained a stool, a table, brushes and dusters, a fire extinguisher, and a small electric heater. Like the 19th century Glaswegian boxes, the London police boxes contained a light at the top of each box, which would flash as a signal to police officers indicating that they should contact the station; the lights were, by this time, electrically powered.

By 1953 there were 685 police boxes on the streets of London. Police boxes played an important role in police work until 1969-1970, when they were phased out following the introduction of personal radios. As the main function of the boxes was superseded by the rise of portable telecommunications devices like the walkie-talkie, very few police boxes remain in Britain today. Some have been converted into High Street coffee bars. These are common in Edinburgh, though the City also has dozens that remain untouched — most in various states of disrepair.

Edinburgh's boxes are relatively large, and are of a rectangular plan, with a design by Ebenezer James MacRae, who was inspired by the city's abundance of neoclassical architecture. At their peak, there were 86 scattered around the city. In 2012, Lothian and Borders Police sold a further 22, leaving them owning 20. One police box situated in the Leicestershire village of Newtown Linford is still used by local police today.

The red police box, as seen at the Glasgow Museum of Transport In 1994 Strathclyde Police decided to scrap the remaining Glasgow police boxes. However, owing to the intervention of the Civil Defense & Emergency Service Preservation Trust and the Glasgow Building Preservation Trust, some police boxes were retained and remain today as part of Glasgow's architectural heritage. At least four remain—on Great Western Road (at the corner of Byres Road); Buchanan Street (at the corner of Royal Bank Place); Wilson Street (at the intersection of Glassford Street, recently completely restored); and one near the corner of Cathedral Square (at the corner of Castle Street, also recently restored). There was also a red police box preserved in the Glasgow Museum of Transport but this was returned to the Civil Defense Trust after Glasgow City Council decided it did not fit in with the new Transport Museum. The police boxes in Glasgow on Great Western Road is leased as a coffee and donut kiosk, Cathedral Square is leased as the "Tartan Tardis," selling Scottish memorabilia, and Buchanan Street is currently under license to a Glasgow-based ice cream outlet. As of November 2011, and restrictions are enforced by the Civil Defense & Emergency Service Preservation Trust to prevent the exterior of the boxes from being modified beyond the trademarked design.

The Civil Defense & Emergency Service Preservation Trust now manages eleven of the UK's last "Gilbert Mackenzie Trench" Police Signal Boxes on behalf of a private collector. Another blue police box of this style is preserved at the National Tramway Museum, Crich, Derbyshire. One of the Trust's boxes stands outside the Kent Police Museum in Chatham, Kent. and another at Grampian Transport Museum. An original MacKenzie Trench box exists on the grounds of the Metropolitan Police College (Peel Centre) at Hendon. There is no public access, but it can easily be seen from a Northern Line tube train traveling from Colindale to Hendon Central (on the left-hand side).

In the City of London, there are eight non-functioning police "call posts" still in place which are Grade II listed buildings. The City of London Police versions were cast iron rectangular posts, as the streets are too narrow for full-sized boxes. One compartment contained the telephone and another locked compartment held a first aid kit.

Fifty posts were installed in the "Square Mile" from 1907; they were in use until 1988.

On Thursday 18 April 1996 a new police box based on the Mackenzie Trench design was unveiled outside the Earl's Court tube station in London, equipped with CCTV cameras and a telephone to contact police. The telephone ceased to function in April 2000 when London's telephone numbers were changed, but the box remained, despite the fact that funding for its upkeep and maintenance had long since been exhausted. In March 2005, the Metropolitan Police resumed funding the refurbishment and maintenance of the box (which is something of a tourist attraction, thanks to the Doctor Who association — see below). Glasgow introduced a new design of police boxes in 2005. The new boxes are not booths but rather computerized kiosks that connect the caller to a police CCTV control room operator. They stand ten feet in height with a chrome finish and act as 24-hour information points, with three screens providing information on crime prevention, police force recruitment and even tourist information. Manchester also has "Help Points" similar to those in Glasgow, which contains a siren that is activated by the emergency button being pressed; this also causes CCTV cameras nearby to focus on the Help Point. Liverpool has structures similar to police boxes, known as police "Help Points", which are essentially an intercom box with a push-button mounted below a CCTV camera on a post with a direct line to the police.

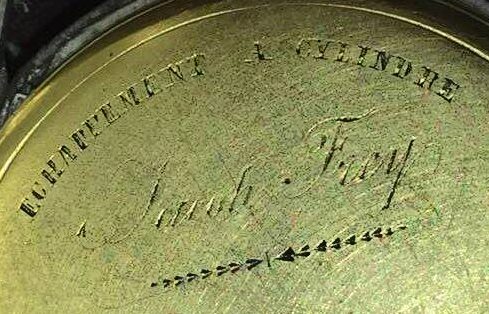

Currently on loan to the BPD Museum

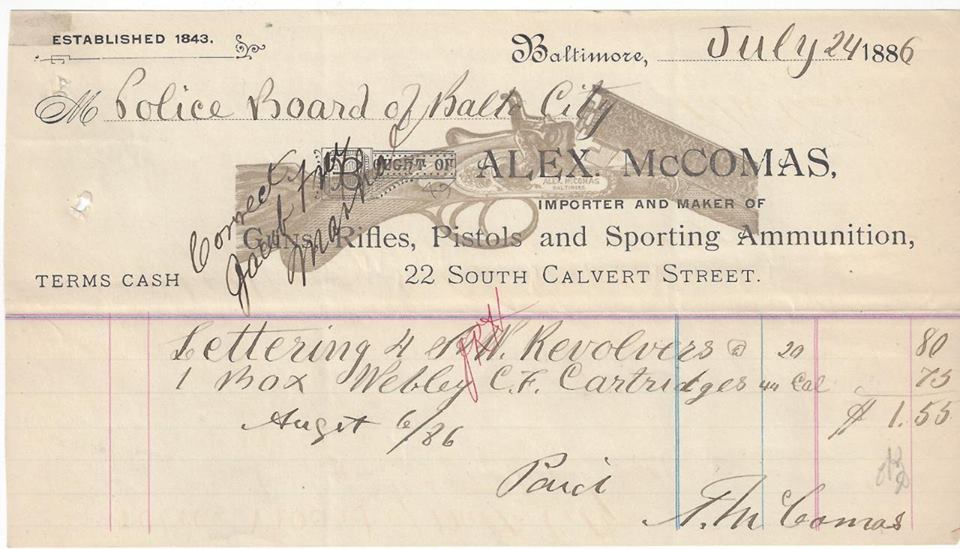

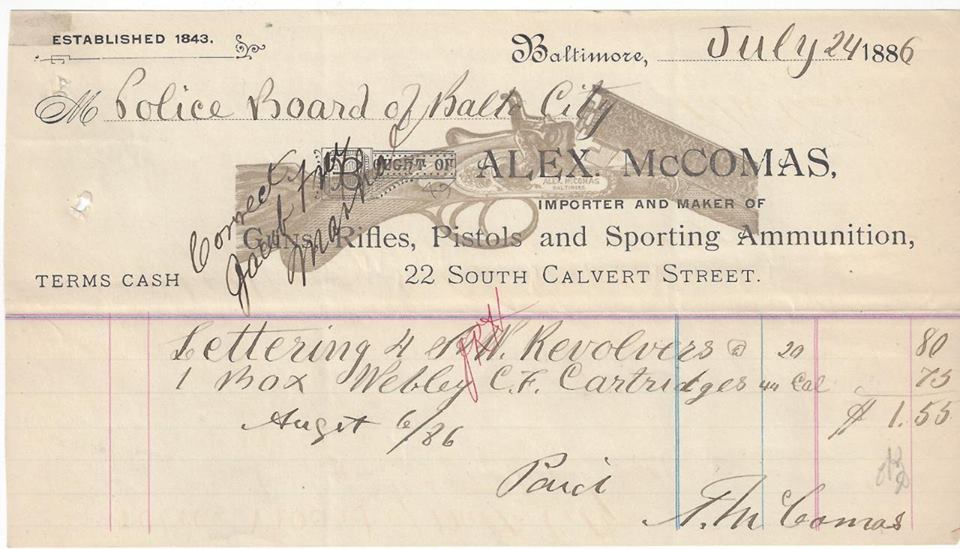

It shows where Marshal Frey ordered some engraving's on our pistols circa 1886

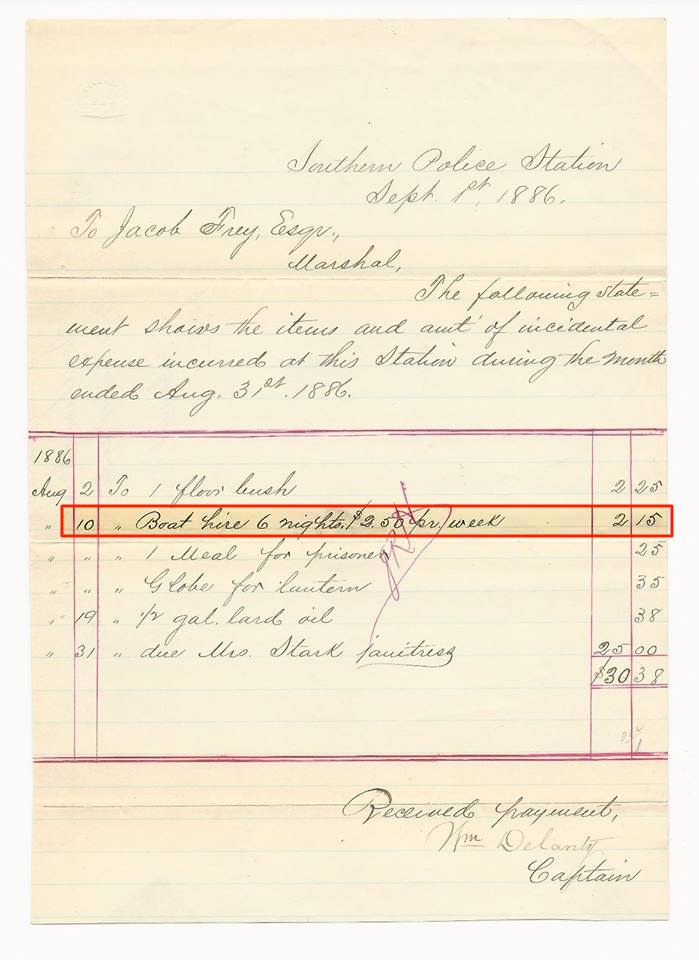

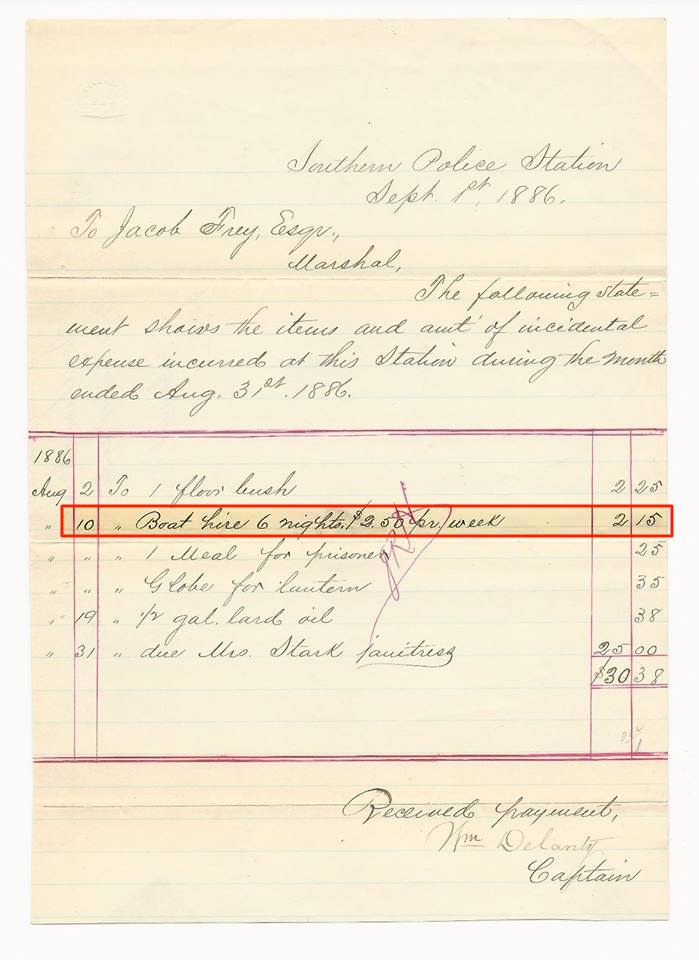

This shows where Marshal Frey rented a rowboat for the Southern District 1886

This is a pic of Marshal Frey's watch and what follows are various shots from various angles