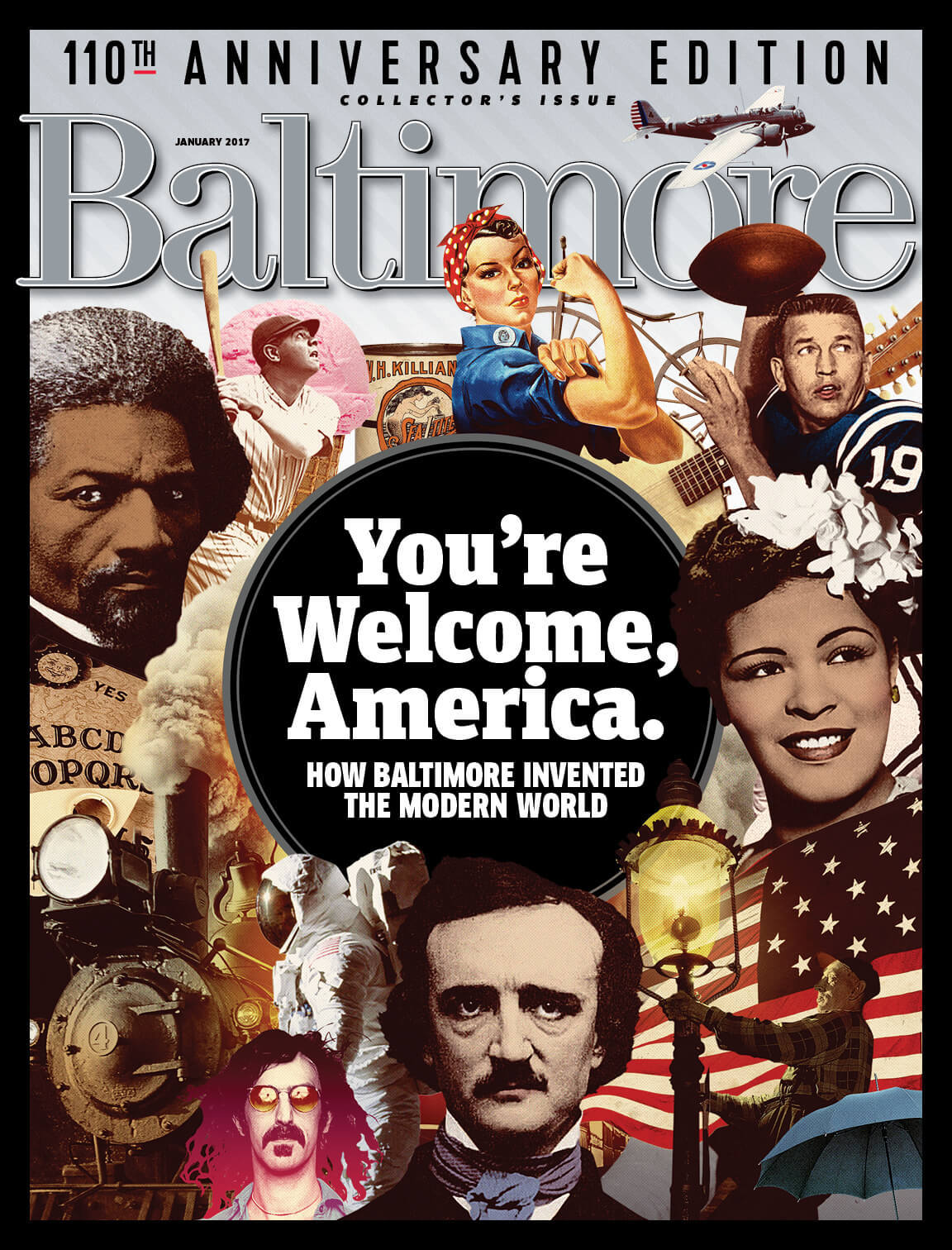

The birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution is tricky to get to. It’s not on any street map, but I can tell you how to find it. Take Lombard Street from downtown, continue past Hollins Market until you reach Monroe, and then make a left. After crossing the overpass, park at the City Farm-Carroll Park community garden. This is where it gets funky. You have to scramble down the hillside beneath the overpass, through woods and thicket—admittedly a surreal setting in West Baltimore—until you reach the clearing and train tracks.

If you go in the afternoon, follow the sun and tracks and start walking west. After a quarter of a mile, other tracks will merge into your path. You’ll pass a warehouse and a rusted steel edifice and start thinking you’ve gone too far and missed it. You haven’t. Amble on another five minutes, and suddenly what you’re looking for will pop into view on the right—a kelly-green, bellybutton-high metal box tagged with graffiti. Next to it, there’s a telephone pole tagged with graffiti, backed up by a stretch of abandoned boxcars and more graffiti, and behind that, a salvage yard.

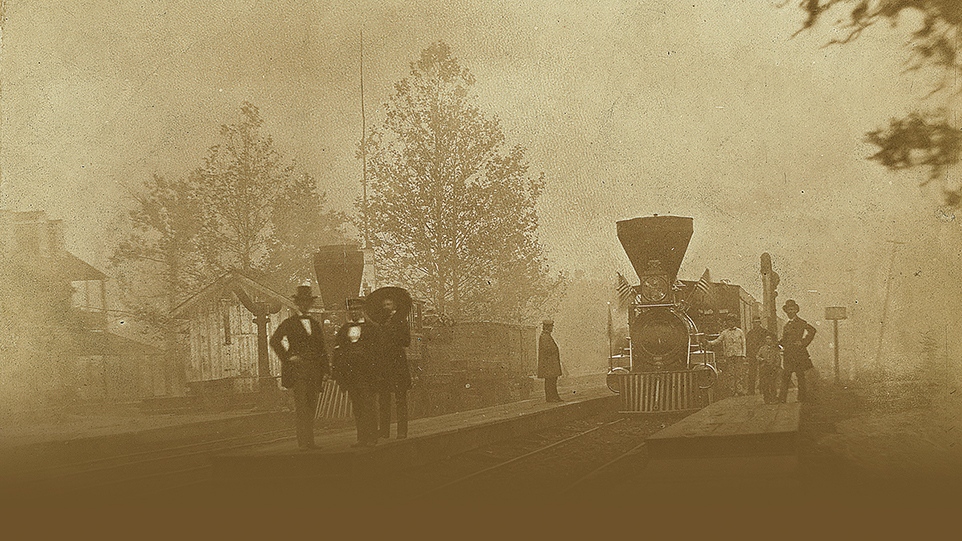

It sounds underwhelming. The history born on this spot and marked by that green metal totem is anything but. Those tracks you’ve just walked down? Turn around. That rail line carried the first commercial passenger and freight trains in the United States. Turn back around, walk a little farther. See that? The 312-foot-long stone arch over the Gwynns Falls? That’s the Carrollton Viaduct. The first railroad bridge built in this country.

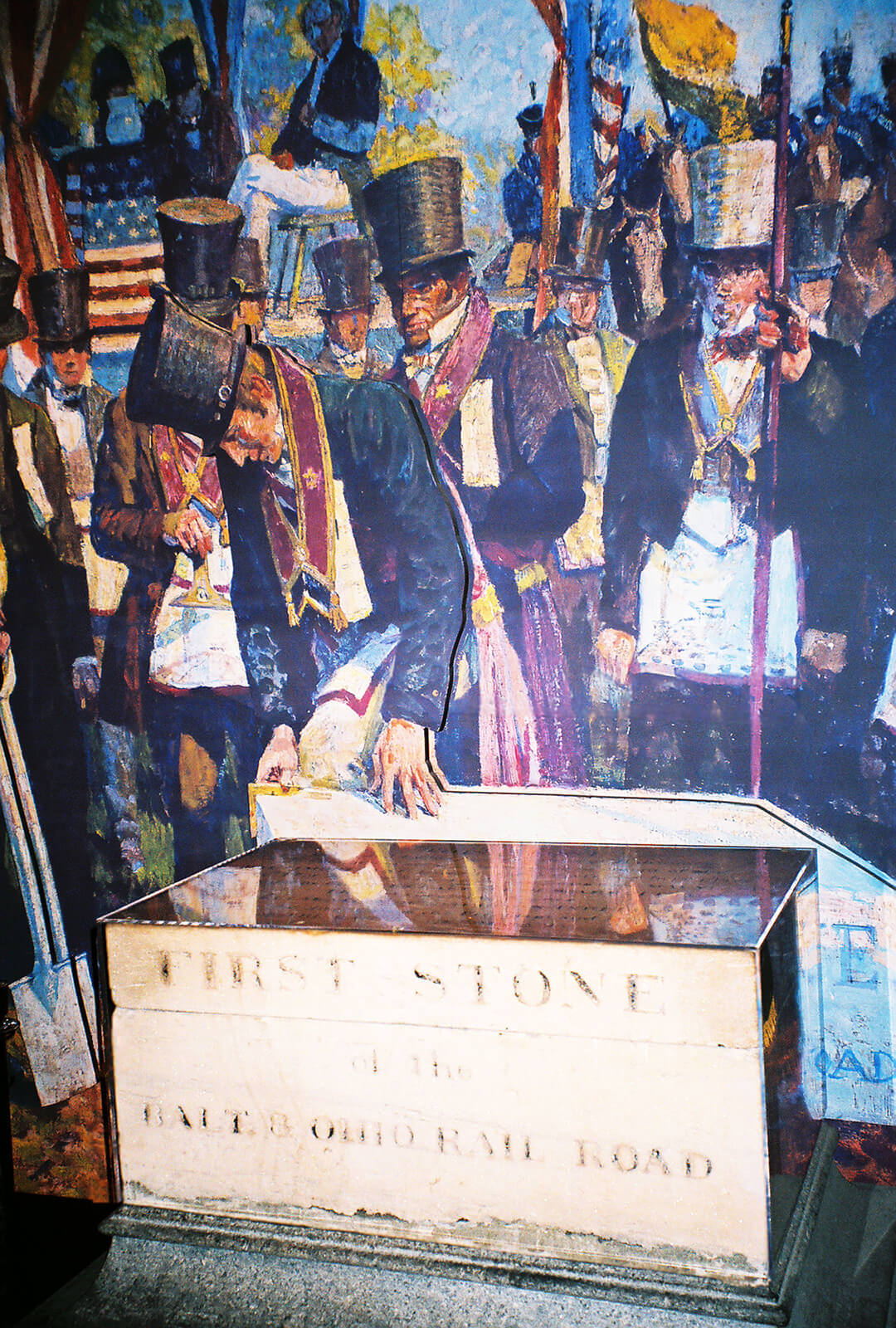

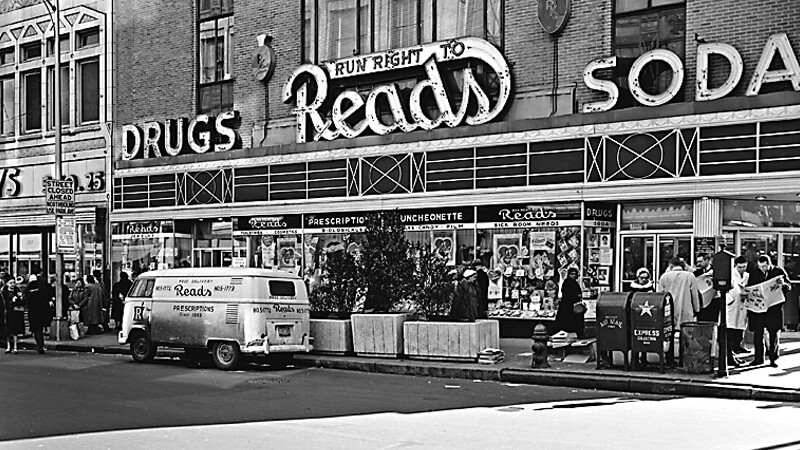

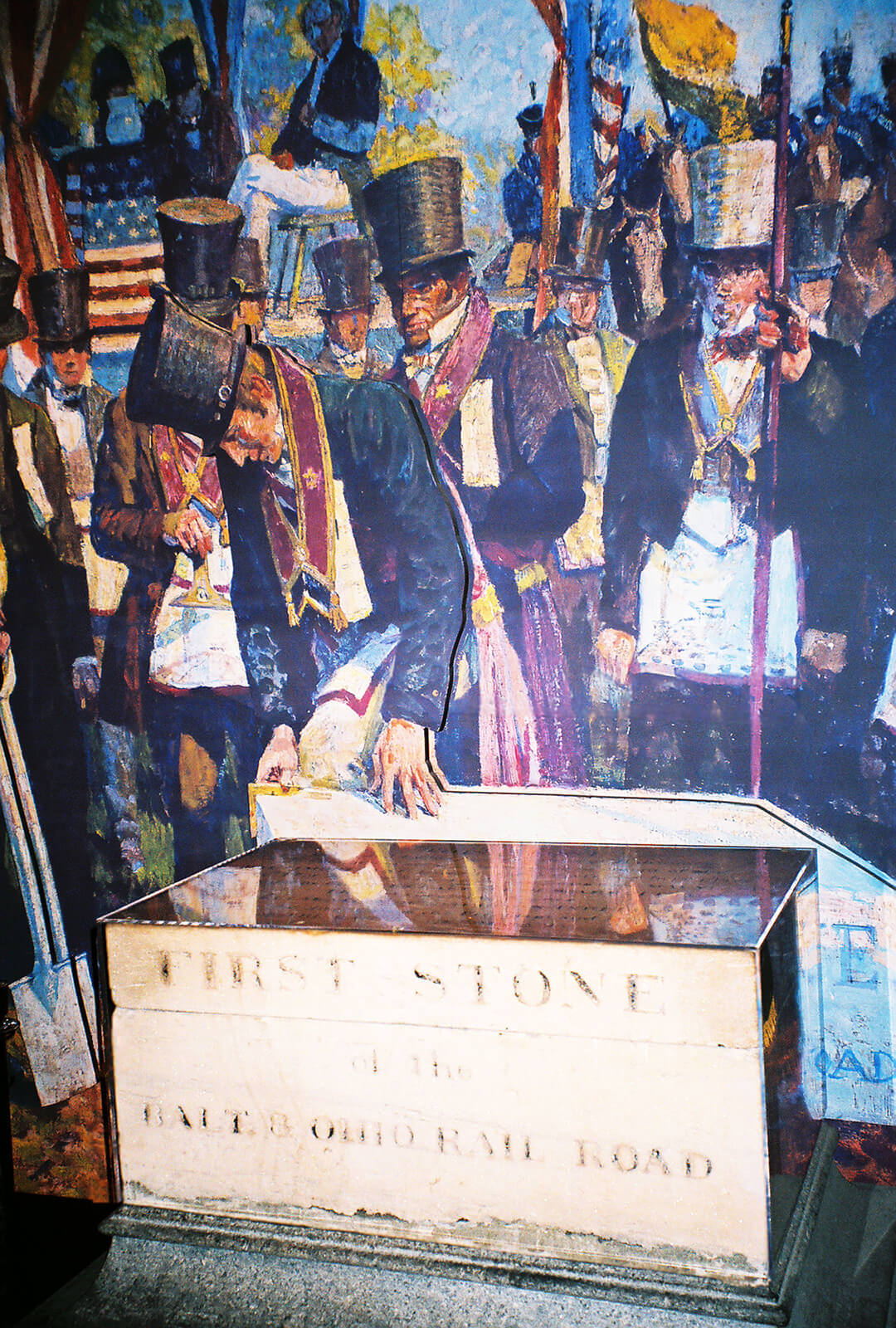

On July 4, 1828, Charles Carroll, the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence, put the first shovel into the dirt here for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. That green metal box is the exact location where the first stone, now kept in the B&O Railroad Museum on Pratt Street for safekeeping, was laid. (A replica sits inside the box). Three-fourths of Baltimore’s citizens gathered to celebrate the occasion with a four-hour parade. The 90-year-old Carroll told the crowd he considered the groundbreaking among the most important acts of his life, “second only to my signing of the Declaration of Independence, if even it be second to that.”

Two years later, the first 13-mile section reached the mills of Ellicott City with wagons pulled on the rails by horses. The steam engine was on its way, however. All along, Baltimore’s founding fathers, taking a tremendous risk on the untested railroad technology being developed in England, had hopes of extending the line through rocky Western Maryland and West Virginia (then Virginia) to the Ohio River. Still, it would take 25 years of hard labor and trial-and-error engineering before the first steam locomotive whistled through the Alleghenies and arrived in Wheeling on New Year’s Day, 1853. In terms of capital—and virtually every citizen of Baltimore had made an initial B&O stock purchase—nothing in the nation’s 75-year history came close to matching the cost of the $30 million project. But the city’s gambit to open the West and build on the economic advantage afforded by its inland, deep-water port would transform Baltimore, then the second-largest U.S. city, and the country like nothing else before or since.

It was an effort so bold, imaginative, and daunting that historian Herbert Harwood Jr. called it “the moonshot” of the 19th century.

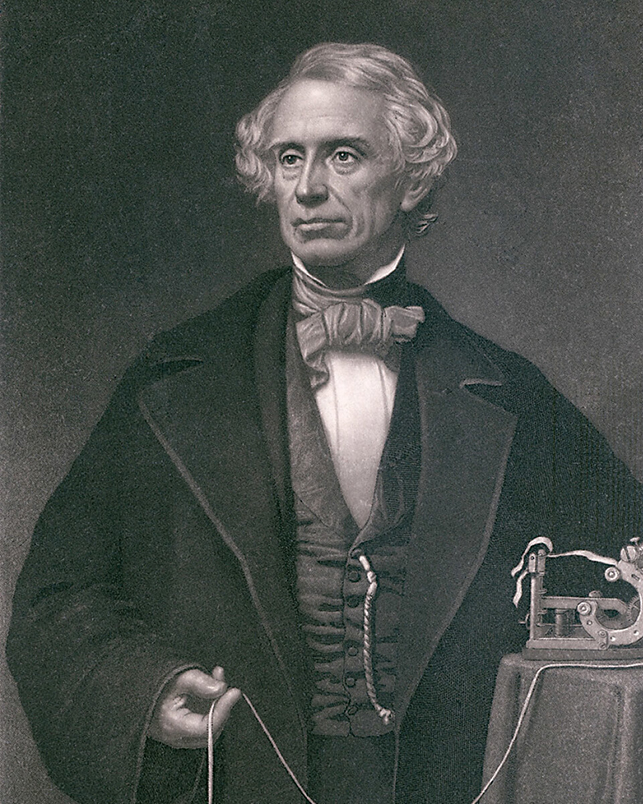

When the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad became the first Eastern Seaboard line to reach the Midwest, it laid down the first link in a giant network that, after the Civil War, would integrate America into a single national economy. The B&O, of course, played a pivotal role in the Union victory, moving troops and delivering key intelligence, but it had also remained an innovator since its inception. The B&O made communication history when it became the first railroad to carry the U.S. mail in 1838. And then again, when it partnered with telegraph companies—the first communication technology of the Industrial Revolution—to string overhead wire next to its rail lines. (It is no coincidence that Samuel Morse’s first message in 1844—“What hath God wrought?”—sped in dots and dashes from the U.S. Capitol along the B&O’s right-of-way to Baltimore’s Mount Clare station.)

By the start of the 1860s, nearly 30,000 miles of rail and 50,000 miles of telegraph cable crisscrossed the country, obliterating previous conceptions of time and distance. In fact, it would be the railroad industry, in an attempt to standardize its schedules, which established the first U.S. time zones.

The launch of the B&0 was not the only seismic event in Baltimore in 1828, however. The formation that same year of an enormous real estate enterprise, the Canton Company—though not permanently memorialized like the B&O with a spot on the Monopoly board—would eventually remake Capt. John O’Donnell’s plantation into one of the great industrial waterfronts of the world. An Irish-born merchant seafarer and one of the richest men in the U.S. when he died, O’Donnell had amassed his 18th century fortune through trade in the Far East—including teas, silks, spices, and opium—naming his estate after the Chinese port.

The cornerstone of the B&O, now displayed at the B&O Railroad Museum, was laid July 4, 1828. Ninety-year-old Charles Carroll, the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence, told the crowd he considered the groundbreaking among the most important acts of his life, “second only to my signing of the Declaration of Independence, if even it be second to that.

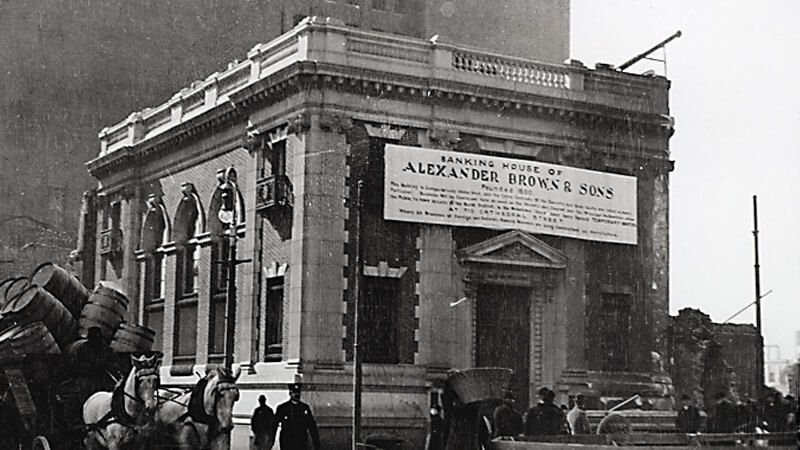

A brief history: The incorporation of the B&O had sparked talk of an economic boom in the pubs, parlors, and boardrooms of Baltimore. In the spring of 1828, Columbus O’Donnell, the captain’s eldest son, and William Patterson, donor of the first acres of the park that bears his name, met with Peter Cooper, a New York capitalist and inventor, to pitch their plan to buy all of the property from Fells Point to Lazaretto Point—the entrance of the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel today. Convinced of the benefits the B&O would endow to Baltimore’s port, Cooper bought a major stake (the only stake, it would later turn out) in the new Canton development corporation, which was given the right to purchase up to 10,000 acres by the state of Maryland. Think Port Covington times 40 in a city with 80,000 people. Two years later, worried his entire investment would be lost as the B&O struggled to create a viable steam engine, it was the polymath Cooper who took it upon himself to design and construct the first successful American-built locomotive—aka the Tom Thumb.

(According to lore, Cooper’s coal-burning prototype raced a horse-drawn car to prove its worth, leaving its steed-powered competitor in the dust before a belt snapped. Bottom line: Although the Tom Thumb lost the race from Ellicott City to Baltimore, Cooper’s steam engine design won the day.)

“I call 1828 the ‘big bang.’ That was the year it all came together and Peter Cooper’s the lynchpin,’’ says Raymond Bahr, a retired physician, Canton native, and local historian, who hopes to create a museum in Canton honoring the community’s industrial past. “Between the B&O and the Canton Company, which is the earliest, largest, and most successful industrial park in America, Baltimore stands at the intersection of U.S. commerce and trade, and technological advances in transportation and communication.”

With its world-renowned Clipper ships, Baltimore already led the nation in shipbuilding when the Canton Company was launched. The USS Constellation, the first U.S. Navy ship ever to set sail, had also been built in a shipyard at Canton’s Harris Creek—the shipyard and creek both long since buried beneath the Boston Street Safeway.

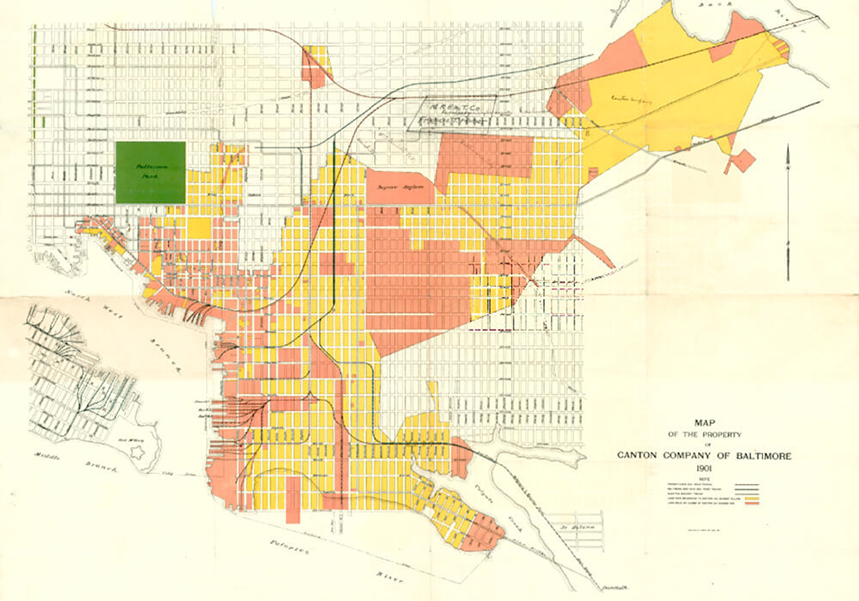

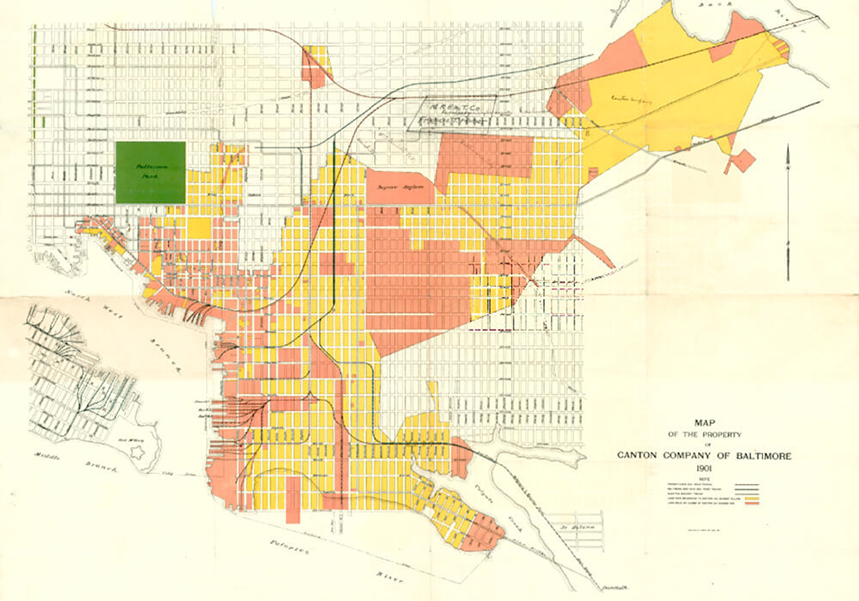

In 1828, new Canton Company development corporation, was given the right to purchase up to 10,000 acres by the state of Maryland, and it became the earliest, largest, and most successful industrial park in the U.S.

In the ensuing decades, the Canton Company slowly began to lease, sell, and develop its vast holdings. At its peak, it owned a swath of land that stretched from Fells Point to Patterson Park—across all of Highlandtown—to the Baltimore County line. Not long after the Canton Company was founded, nearby oyster beds and the city’s expanding rail and labor force would establish the city, and Southeast Baltimore in particular, as the canning center of the U.S. (See: the American Can Company complex.)

Shipbuilding, lumber, iron, coal, and canning companies followed on the waterfront—as well as cotton duck and steel-rolling mills, distilleries, beer makers on Brewers Hill—and the largest U.S. copper smelting plant. Some 69 manufacturing companies were in business by 1871. The Canton Company built wharves and piers and initiated two railroad ventures of its own the Union, later bought by the Northern Central, and the Canton Railroad. If you’ve ever kayaked in the harbor off the Canton Waterfront Park and wondered about the towering steel structure in the water there, it’s the remnant of a massive lift that once pulled railcars—crossing on barges from Locust Point—onto Canton trains.

Major oil refineries arrived, too. Up until 1925, Oklahoma crude was still being sent via pipeline to Baltimore for refinement in Canton.

But the Canton Company was developing more than just an industrial powerhouse. It laid out Southeast Baltimore’s familiar grid streets and its iconic—and then inexpensive—rowhouses for its blue-collar workers. (The proximity of Baltimore’s industry and marble rowhouse stoops in neighborhoods like Canton would prove a bonanza for Bon Ami cleaning powder.)

And, now long forgotten, Canton even flourished as a thriving summer destination. With music and dance halls, roller coasters, a roller rink, a shooting gallery, taverns, restaurants, and a swimming pier, it was billed as “the Coney Island of the South,” drawing 600,000 visitors a season at the turn of the 20th century.

The intertwined origin stories of the B&O and the Canton Company are crucial to understanding the history of Baltimore—and subsequently the United States—because nearly everything that happened during the city’s boom over the next century and a half is connected, one way or another, to those two landmark events. George Peabody, William Walters, and Enoch Pratt were each involved with the B&O. Johns Hopkins became one of the directors of the railroad in 1847 and bequeathed his vast B&O stock holdings to fund the city’s elite university and hospital.

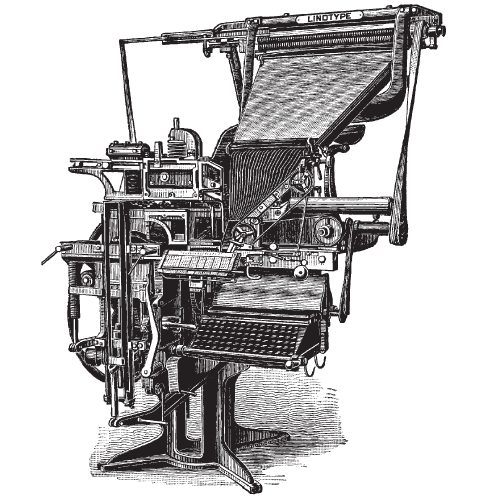

The immigration pier at Locust Point—the second or third busiest in the country (depending on the year)—was built by the B&O after the Civil War, delivering thousands of Eastern and Central European workers into the port’s factories. That pier also welcomed the German-born Otto Mergenthaler, who would invent the modern typesetting machine and send U.S. literacy rates skyrocketing. It also welcomed Sen. Barbara Mikulski’s Polish Catholic grandparents and Sen. Ben Cardin’s Jewish grandparents.

When Bethlehem Steel joined the industrialization of the port in 1916, it amassed the largest steel plant in the world at Sparrows Point.

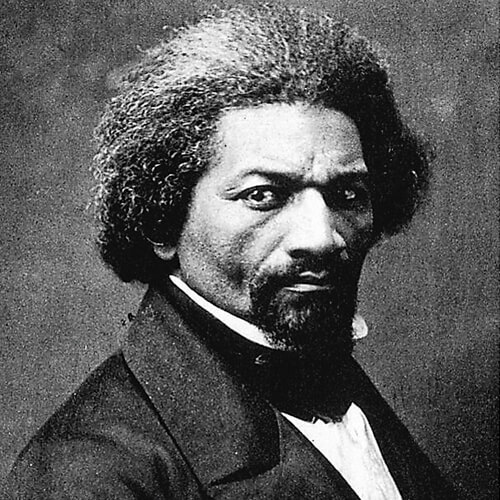

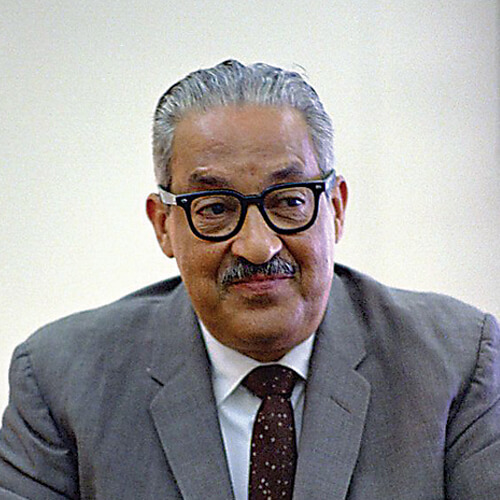

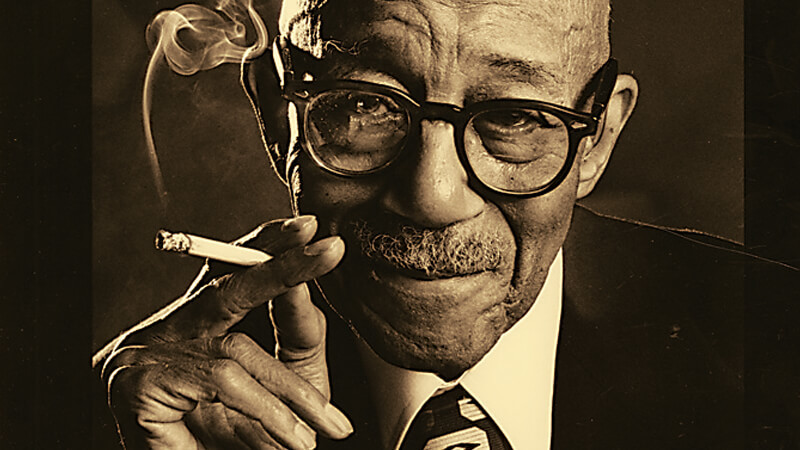

Those jobs, as well as others around the port—at General Motors, Lever Brothers, Western Electric, in the rail yards—also attracted African Americans to Baltimore. It’s no surprise that both Thurgood Marshall and his father worked for the B&O.

– Sean McCabe

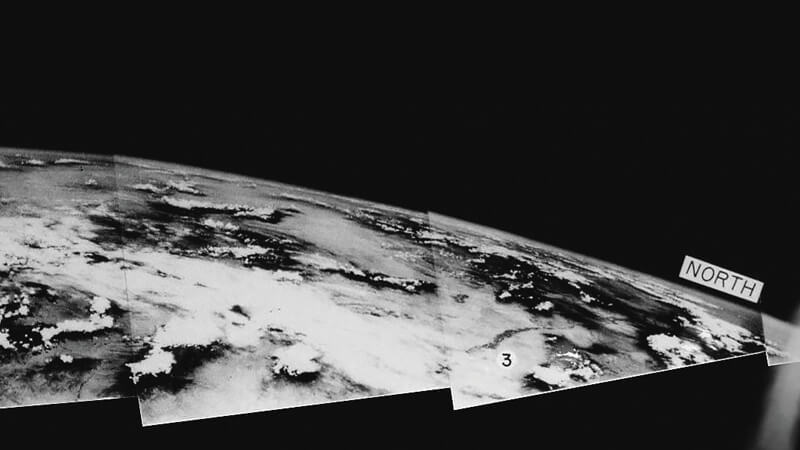

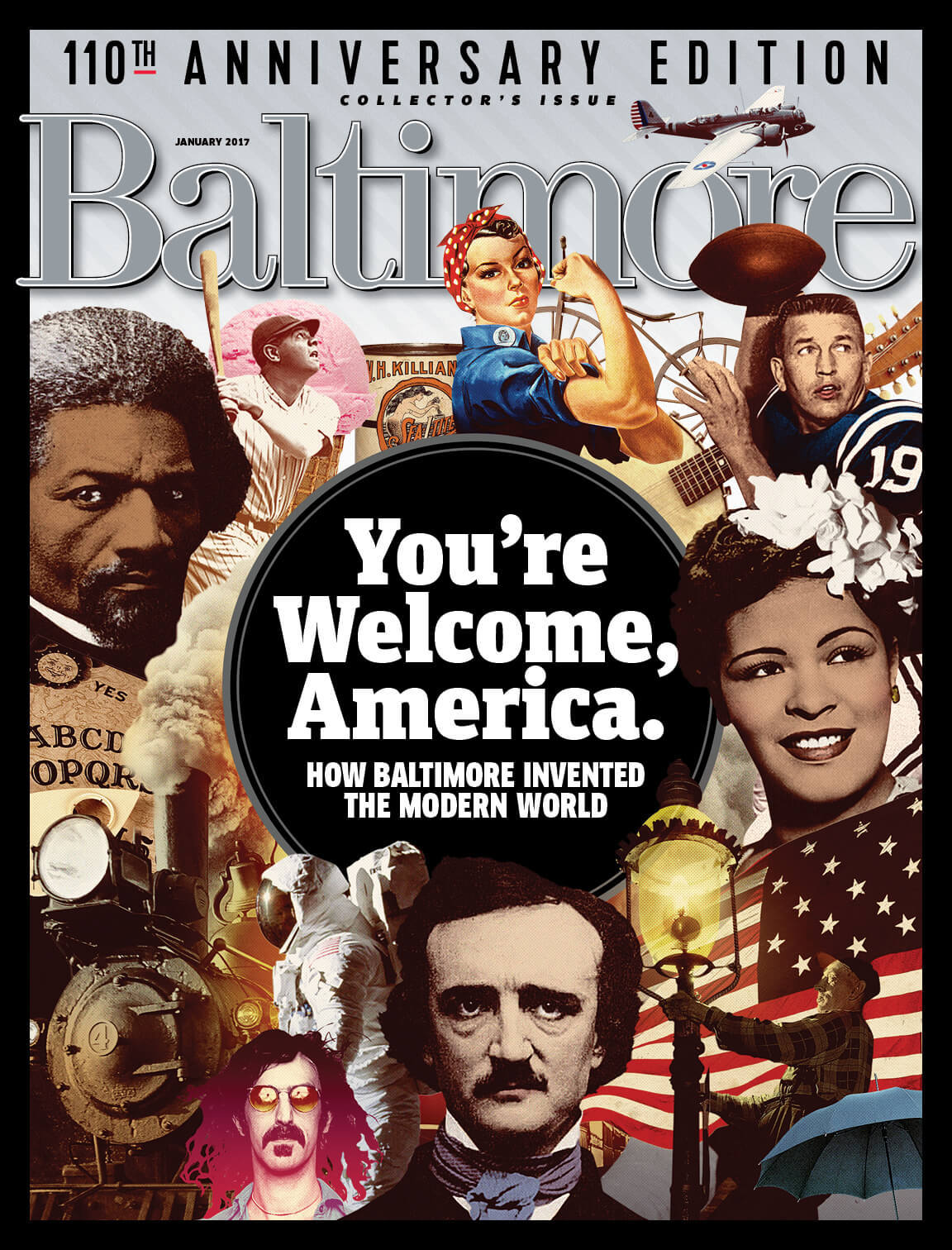

It is also no surprise that Baltimore, so long on the cutting edge of modern America—from the moonshot of the B&O to the camera that captured Neil Armstrong walking on the moon—produced so many peerless innovators. It’s a list that includes geniuses as varied as Abel Wolman, who perfected purified public drinking water, and Eubie Blake, whose hands are enshrined in plaster casts at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

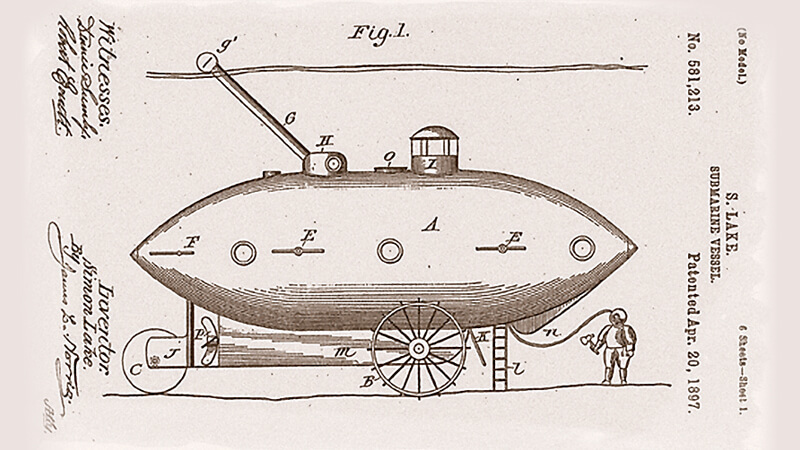

In the following pages, we list 110 ways that Baltimore helped invent modern America. The number is a nod to Baltimore ’s 110th anniversary as the oldest continually published city magazine in the country. More importantly, the list is a reminder that Baltimore was—and is—one of America’s greatest cities. We tried to put the city’s most prominent contributions up top, but the list is largely chronological. We don’t pretend to be able to discern whether the invention of the electric streetcar is more significant than the invention of the submarine, or whether Billie Holiday or the Baltimore Colts had a more profound cultural impact. What we do know is that in Baltimore, we walk in the footsteps of giants every day.

—Ron Cassie