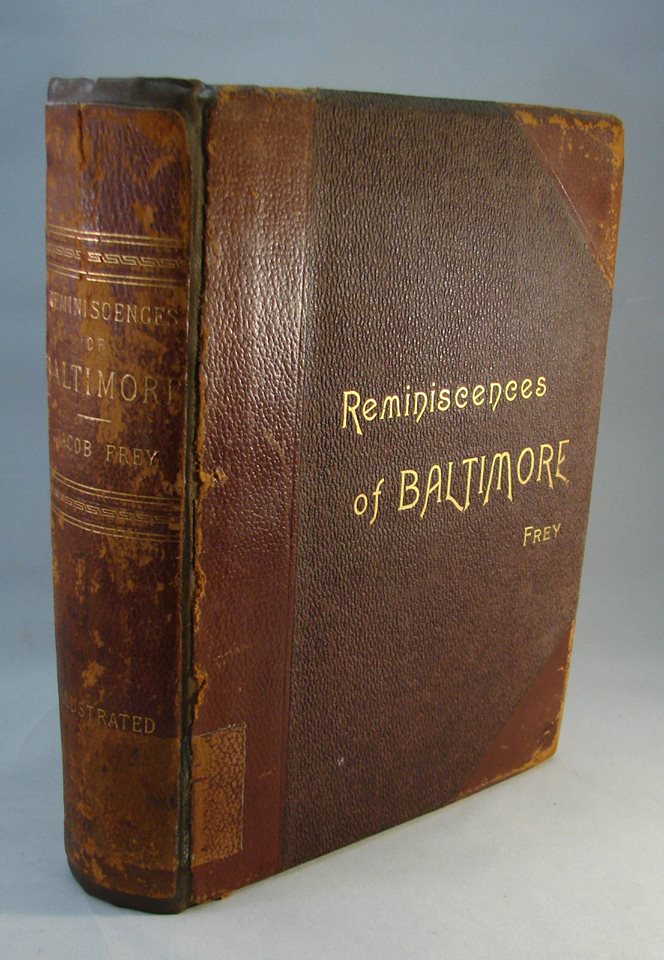

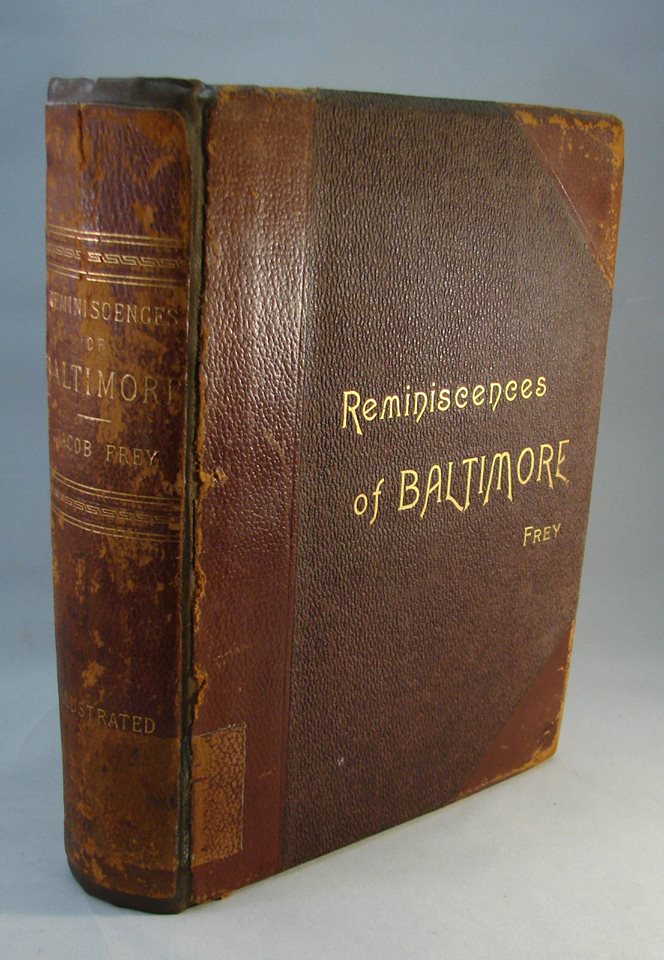

Marshal Jacob Frey

During the railroad riots of July 1877, a situation occurred that demonstrated the abilities of the Baltimore police force. Luminous qualities of the Baltimore Police. The firemen of the B&O Railroad's freight engine squad quit their work on Monday, July 16, 1877. The residents of this city had already lost their minds when the police in Baltimore—and Deputy-Marshal Jacob Frey in particular—kept their composure, courage, and resolve. The firemen who work on the freight engine squad for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad went on strike after having their pay reduced by 10%. These men claimed that although they were already making poverty-level wages before to the reduction, they would now be unable to support a nomadic lifestyle. The Railroad, however, claimed that they were forced to make pay cuts and were unable to pay increased wages due to a decreasing trend in the nation's general commercial interests.

At first, there were roughly 100 of them. They frequently departed the city on their trains, but when the engines stopped to pick up coal, they deserted their positions and refused to go any further. The strike first appeared to be manageable, but as the first day went on and reports that the unrest had reached Martinsburg and that the militia had been called out spread, things started to get more serious. The police arrived right away. Between Baltimore, the Relay House, and a squad of twelve at Camden Junction, they were posted in groups of two and three at various locations.

Similar to other moments of unrest in Baltimore, both before and after this incident, the first day went by quite peacefully, however in this instance few freight trains departed the city. But on the second day, Tuesday, July 17, 1877, the excitement started. A misplaced switch at a trestle near the bottom of Leaden Hall Street, Spring Garden, partially destroyed a freight train of 18 laden cars coming from the West and headed for Locust Point. The engine and a number of the cars were flung into a gulley. Two firemen were shot during a scuffle in Martinsburg, according to the news. The Baltimore and Ohio Company employees convened a meeting at early light and decided to support the strikes but first try to reach a settlement with the business.

Conciliation fell through, and the strike continued. The West Virginia government requested troops from President Hayes on Wednesday [18 July 1877], the third day of problems for the B&O, and a proclamation was immediately made by the President. Quickly, troops were dispatched. Naturally, all of this had an impact in Baltimore, but on that particular day, there were no aggressive protests there. The passenger trains arrived and left as usual, but the freight industry was essentially nonexistent.

The Business made the decision to stand firm in its position and offered a $500 reward for information leading to the capture of the person or people responsible for the Spring Garden wreck. The disturbances in Martinsburg persisted on the fourth day [July 19, 1877], but there was no outburst in Baltimore. Any excitement would have to wait for almost a full five days to occur here. Baltimore, though, was more ecstatic when it came than it had been since the war.

When it was learned that the strike in Cumberland was about to take on a national scale at around 3 p.m. on Friday, Governor Carroll met with the officials of the Baltimore and Ohio Company and concluded that the military's presence in Cumberland was essential to maintaining peace and order. Half an hour later, he gave Brigader-General Herbert, who was in charge of the First Brigade, M. N. G., the order to travel to Cumberland. At the same time, he issued a proclamation urging the rioters to stop. The military should be called to their various armories by a "military call" from the bells, General Herbert and Governor Carroll discussed shortly after. Governor Carroll opposed to this, and General Herbert again requested that the bells be rung after trying unsuccessfully to summon the soldiers at the armories through the conventional methods. This was carried out, and a serious mistake was demonstrated.

The City Hall fire bells rang the 1-5-1 call at twenty minutes to six. People quickly packed the streets around the armories with men and boys of all ages who supported the strikes after realizing what it meant. About that time, the factories had finished their job, and all of the workers contributed to the growth of the crowds. The mob, which numbered at least 2,000 people, was gathered in front of the Sixth Regiment's armory at Fayette and Front streets. Oddly enough, the regiment's officers requested that police officers be deployed to clear the area so that the regiment may march on to Camden station in a message to the police headquarters.

Due to the outdated system that was in use at the time, not enough police officers could be gathered in time for the job, and after two hours, the throng had grown so huge that no force could manage it.

Around seven o'clock, the Sixth Regiment Armory started experiencing problems. One of the windows received a brickbat.

Officers Albert Whitely, James Jamison, Oliver Kenly, and Roberts, four policemen stationed at the door, bravely manned their risky vigil despite the stones, missiles, and jeers that followed, even though the four militiamen who had been with the cops had been called in. Around 8.15 o'clock, when the march was scheduled to begin, the crowd was enraged and hostile. Yet, the businesses destemmed in order to pass the rioters. When they first appeared on the street, there was such a widespread uproar that it forced the men to retreat back inside the structure. The next time they emerged, they were instructed to open fire. The first company opened fire in the air, but the subsequent companies were under such intense fire that they were forced to fire their weapons into the crowd. From that moment on, there was constant and widespread firing along the march to Camden station, which led to the deaths of roughly a dozen individuals and the serious injuries of many more.

Although being badly attacked and having every opportunity to fire, the Fifth regiment chose not to utilize its weapons. The men marched through a hail of stones and other projectiles admirably. They numbered 250 in total. At the intersection of Eutaw and Camden streets, a substantial group of unkempt guys barred their path. As the bricks were falling quickly when they came to a stop, Captain Zollinger advised his men not to open fire.

Then he gave the order for them to be ready to charge the depot with their fixed bayonets. Captain Zollinger drew his sword and yelled at the crowd to move aside so the order could be carried out. The Captain faced a strong man who swiftly knocked him to the ground. Among the cries and cheers, the Captain fired several shots.

Inviting the regiment to charge the depot was the crowd. The building was set on fire shortly after the regiment arrived at the station. The rioters tried to stop the firemen from doing their jobs, but fortunately their attempts failed and the flames were reduced to embers and eventually to ashes.

With the exception of a few brief newspaper articles, the brave duty of the police during these rebel raising times has never been adequately acknowledged. Every time, they intimidated the crowd while the soldiers made everything worse.

Twelve soldiers were equal to one police officer. The police kept an eye on all the storage facilities and guarded the military until well after midnight. When our police guarded the fire fighters, their apparatus, and the hoses they utilized, the buildings were spared. The mob opened fire on them, inflicting some casualties. In response, they wounded many of the mob members and made numerous arrests.

The order sending the soldiers to Cumberland was afterwards revoked as a result of this enormous commotion, and Mayor Latrobe made a proclamation to that effect.

These were the days when the police force's effectiveness was put to the test. Jacob Frey, a deputy marshal, was in charge of the area around Camden Station. He didn't sleep for almost 70 hours while working alone to keep the crowd under control. On that Friday, before any of his officers could gather and before the military showed there, Frey had purged several hundred ecstatic and rowdy men off the platform and the front sidewalk. But as soon as further help was on the way, Deputy-Marshal Frey jumped into the crowd and quickly apprehended two of the troublemakers. They were taken into his custody without incident and brought to the Southern District Station House, where Frey himself made the arrests.

On Saturday night, people gathered once more near Camden Station. Around nine o'clock in the evening, a fire alarm roused the rioters, who raced towards the police lines that had been set up. The rioters opened fire with shots, injuring numerous officers in the process. The troops were then instructed to maintain their composure by Deputy-Marshal Frey, and a second later, with their pistols drawn, the order to "Take Aim, Fire" was given. Each officer seized a prisoner as they pushed forward and fired low shots. Fifty people were detained; several guys died and numerous others were injured. At 11:00, there was another outbreak, leading to 53 additional arrests. On Sunday morning, enormous masses gathered once more at Camden Station and pressed up to the Fifth Regiment's picket lines. Because of how things appeared, Deputy-Marshal Frey requested a squad of twenty police officers. The Deputy-Marshal personally took responsibility of them when they arrived. He urged everyone who had been disposed of peacefully to return home and warned the audience that he would "clean that street." Several of them did so, but a large number stayed. The Marshal ordered "Advance" to his men as he turned to face them, and the rioters were quickly chased away. They were terrified of the Deputy-Marshal because they knew him.

Every attempt was made to defend the city once the violence had grown so dangerous. The United States immediately ordered soldiers from New York and other locations to Baltimore. Eight companies of soldiers from New York Harbor arrived with General W. S. Hancock, who also had two fully manned warships with a combined crew of 560 men docked in the Patapsco. The Police Board administered oaths of office to several hundred special policemen. William M. Pegram, Alexander M. Green, C. Morton Stewart, Frank Frick, E. Wyatt Blanchard, James H. Barney, J. L. Hoffman, Robert G. Hoffman, W. Gilmore Hoffman, John Donnell Smith, William A. Fisher, Frederick von Kapff, and Washington B. Hanson were some of the well-known residents who were among them. With regular badges provided, they performed admirably. The majority of the regular police officers worked more than fifty hours straight without taking a break from their duties. The massive display of force by the police and army overwhelmed the rioters, and the unrest eventually subsided. The following Saturday, ten troops were stationed at each freight train as it traveled along the road.

More or less, the strikes in other places persisted, but they ended in two weeks. Thankfully, there was no trouble on the Northern Central railroad. The inquest jury for the man killed by the Sixth Regiment was highly thorough in its investigations, and after spending several days gathering testimony, it reached a conclusion that found the rioters responsible for the unrest but accused the regiment of firing too quickly and randomly. It found fault with the lack of additional police presence in and around the armory. Nonetheless, this was all the Marshal's fault for not receiving enough notice from the military authorities. The police department's contribution to the illustrious struggle will always serve as a testament to its valor and effectiveness.

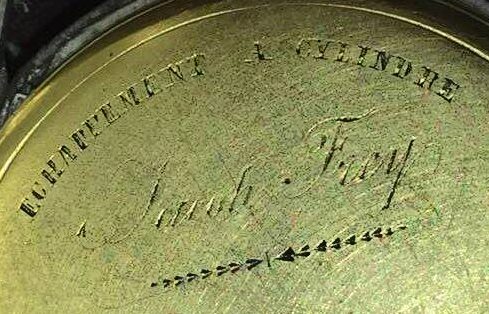

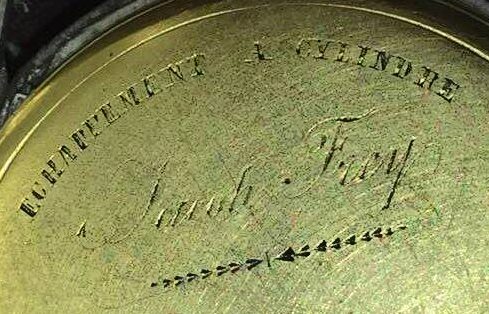

Jacob Frey's Watch

Union Soldiers Attacked

In a border city with strong Southern sympathies, Baltimore's police had the difficult task of guarding union soldiers passing through on their way to the southern battlefields. Unlike other passengers, the soldiers were transported slowly to the streets in the course cars during the early months of the civil war. The billing masses, who were yelling in support of Jefferson Davis, noticed the wrapping tape to assault, and they put on a show in the best riding Baltimore has to offer. Against the automobiles, they hurled stones and other projectiles. Yet, on April 19, 1861, the mob tried to obstruct the soldier's progress, and it was a crucial day for the Baltimore police force. Tamales stacked a dray load of sand, a pile of cobblestones, and some light anchors on the track near Gay and Pratt streets in order to block it.

Police Heads Imprisoned

Following their exit, 220 union soldiers made an attempt to march on Camden station. It served as the command to attack. During the subsequent melee, the rioters made an attempt to steal the soldiers' rifles. Police attempted to defend the Union soldiers with guns drawn and threats to fire, but their efforts were ineffective. 36 soldiers were hurt, and four soldiers died. Similarly, 12 people were slain. Some weeks later, General Banks, who was in charge of the Union forces in Baltimore, made the decision to seize control of the police force. Marshal Kane was taken into custody and lodged in Fort McHenry. He detained the final three commissioners in the later hours. They were sent to prison and kept there for over a year. Those with union sympathies were named to the new department's commissionership and placed on the federal payroll. After the war, the agency started implementing ideas that have now spread throughout the whole American police force. The patrol van, the helmet, and the police telegraph box were among the new inventions. Police had to carry highly inebriated prisoners to the station house on their backs until about 1885, at which point they commandeered a wheelbarrow. Baltimore is thought to be the second American city to use patrols after Chicago. Deputy Marshal Jacob Frey learned about police patrol wagon history while reading an illustrated magazine in the gymnasium of Central's station. The Board of Commissioners (BOC) expressed a passing interest when he presented the concept to them. Frey didn't give up on issues he was passionate about; a few weeks later, he brought the issue back to the board's attention; they had previously forgotten about it but had made a commitment to look into it. According to Frey, the Police Telegraph Box System and Wagon represented the future of policing.

Telegraph Box System

Deputy Marshal Frey intervened on its own when the BOC did nothing. He dispatched department representatives to Chicago to observe the operation of the "New Fanged" patrol wagons. According to an old record, "they were charmed." They also investigated Chicago's innovative "Police Telegraph Box" system while they were there (the Call Box). Both of these instruments arrived in Baltimore by the fall of 1885 as a result of Baltimore's journey. Baltimore became the second Department in the nation to deploy the Police Telegraph System after Chicago, according to accounts in the Baltimore Sun newspaper. From 1885 until 1986, when Baltimore established a 1-800 number for police to use when radio use was undesirable, these boxes were still in use there. By 1988, all boxes had been retired from service.

The Police Helmet

A rule was created in Baltimore in 1886 and had already been worn in other places. Alford J. Carr, a commissioner, presented it. It replaced the derby that police officers previously wore. Commissioner Carr stipulated that the helmet should be pearl gray in the summer and black in the winter. During that time, only sergeants and patrolmen wore helmets, which were symbolic of rank. The marshal, his assistant, the captains, and the lieutenants were there. At the time, it was reported that the home's hygienic conditions were first-rate, allowing the policemen a chance to arrange adequate ventilation.

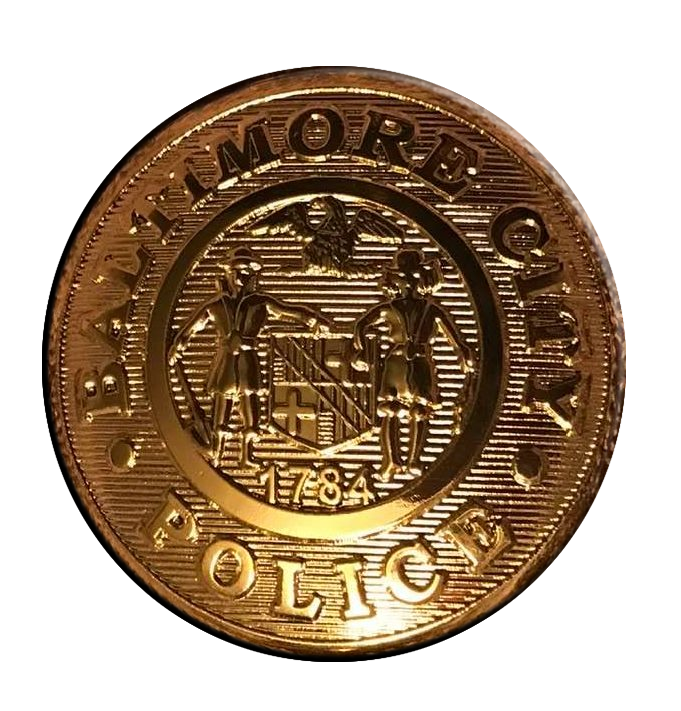

Friday, Aug 20, 1886, New Badge

New badges for the police captains: Today, the city's police captains will be visible wearing new badges. A directive to that effect was issued by the police board. According to Marshall Frey, the captains had long grumbled that their old badges were the same as those worn by almost every watchman or private detective in the city. The ancient badges were simply a circle with a star inside it, along with the wording "Captain of Police." The new badges are really attractive and much more elaborate. Around 2 12 inches long and 2 inches wide, the form is shaped like a shield. and silver. On the face, the Maryland Coat of Arms is prominently shown. Above the coat of arms is inscribed a "eye." Underneath, the word "Capt." can be seen. John W. Torsch, the maker of the new badges, Because the force is a state organization, according to Marshall Fray, he believed it fitting to include the Maryland coat of arms on the badge. He continues by saying that the "eye" is meant to serve as a reminder to the captains to remain vigilant at all times.

Jacob Frey served as Marshal from Oct 15, 1885 - Jul 12, 1897

Marshal Jacob Frey was no longer actively associated with the Police Department as of July 12, 1897. Capt. Samuel T. Hamilton was chosen on October 7th, 1897, to take Marshal Frey's place as Marshal of Police. Marshal Hamilton was a distinguished Civil War officer with unquestionable courage and moral rectitude. He had served on the Western frontier for many years after the American Civil War, taking part in the never-ending wars against the Sioux and other Indian tribes as settlers and pioneers pushed toward the setting sun, constructing towns and railroads while attempting to subdue the wilderness and its native inhabitants. Captain Hamilton and his troop made a fruitless attempt to re-enforce Gen. George A. Custer and his severely undermanned men during the Sioux campaign of 1876 when they were outnumbered ten to one by the Indians in the valley of the Little Big Horn. The Seventh United States Cavalry died on June 26, 1876, and the day after that, on June 27, the reinforcements came, worn out from their fantastic journey across the nation. The remainder of the campaign was fought by Captain Hamilton and his troop, and as a result, Sitting Bull, the legendary Indian war leader, was forced across the Canadian frontier.

The Harbor Thieves

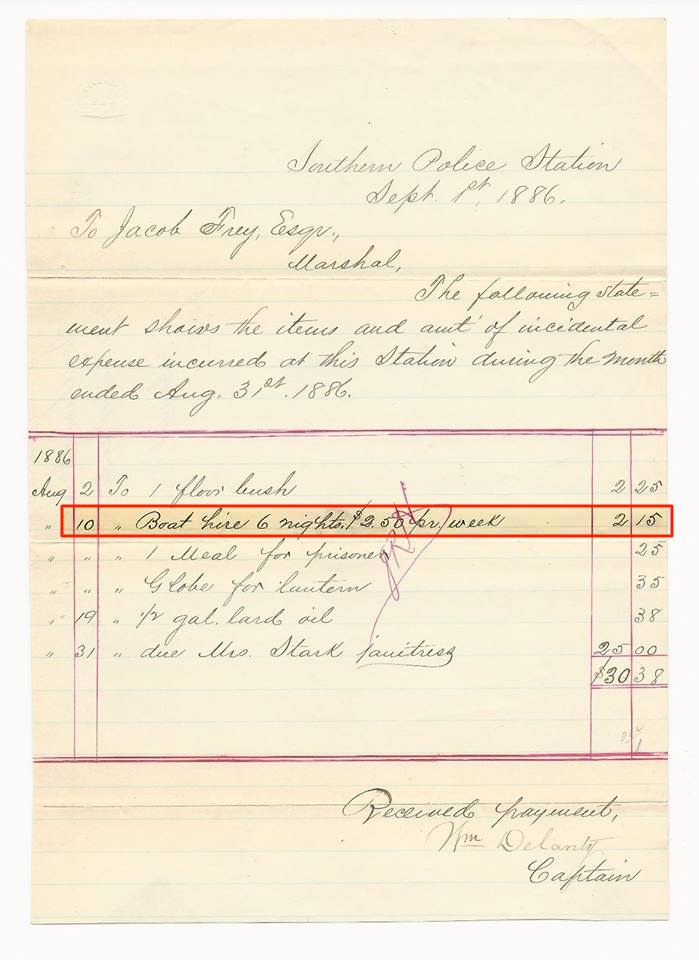

The Sun (1837-1987); Jul 27, 1886; pg. 4

The criminals who plundered multiple vessels early on Sunday in the harbor have not yet been apprehended by the police. The burglars are thought to be the same ones that looted a ship near Washington late Friday evening. All along the coast, there have been reports of thefts. The authorities have reason to believe that a group of professional criminals are carrying out the thefts since they have been carried out with remarkable skill and organization. Police Marshall Frey stated that he had submitted the following written recommendation to the board of police commissioners regarding the need for better facilities for apprehending thieves: "There exists a necessity for a harbor police boat, as many depredations and other offenses are committed on vessels and along the shore by persons in small boats, the policeman on land being unable to see or hear them in many instances, and in many cases when seen or heard, in many cases when they are not." About 18 years ago, we had a yawl boat patrolling the harbor, and it did a good job, but the need for police officers on the ground forced us to forsake even that basic harbor security system. The police board acknowledged the significance of this suggestion and included a clause in an act to more precisely describe the special fund under the control of the board and to fund a harbor patrol boat, but the clause was removed when the act was ratified by the previous legislature. The special fund, which is used to construct station houses and pay for patrol vehicles and pensions, is funded by fines levied by police magistrates. The Marshal claims that harbor police boats in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and other places are very helpful in protecting the property of vessels, and he claims that Baltimore needs a steam yacht with around four rowboats. All through the night, the yacht could move up and down the harbor, and rowboats could patrol the docs at its command. The yacht should have a regular police captain. In his estimation, it would take an additional 15–16 police officers to complete the task completely. The Marshal added that the inhabitants of the city are unaware of how many thefts take place at the harbor. The sole ship Jewelry, clothing, and money are the types of thefts that are typically covered in the news, but produce thefts account for by far the biggest losses because it is done so skillfully that neither the ship's captain nor the owners of the products are aware of the theft until the Produce is removed and a shortage is noticed. The Marshal suggested the installation of the port police boat in order to stop these crimes and to apprehend the professional thieves. According to the board's president, Mr. George Colton, the board would need special legislation to build the harbor system. The board acknowledges the need for a patrol boat, along with the Marshal and Deputy Marshal.

Guarding The Harbor

Reported for the Baltimore Sun

The Sun (1837-1987); Jul 31, 1886; - pg. 6

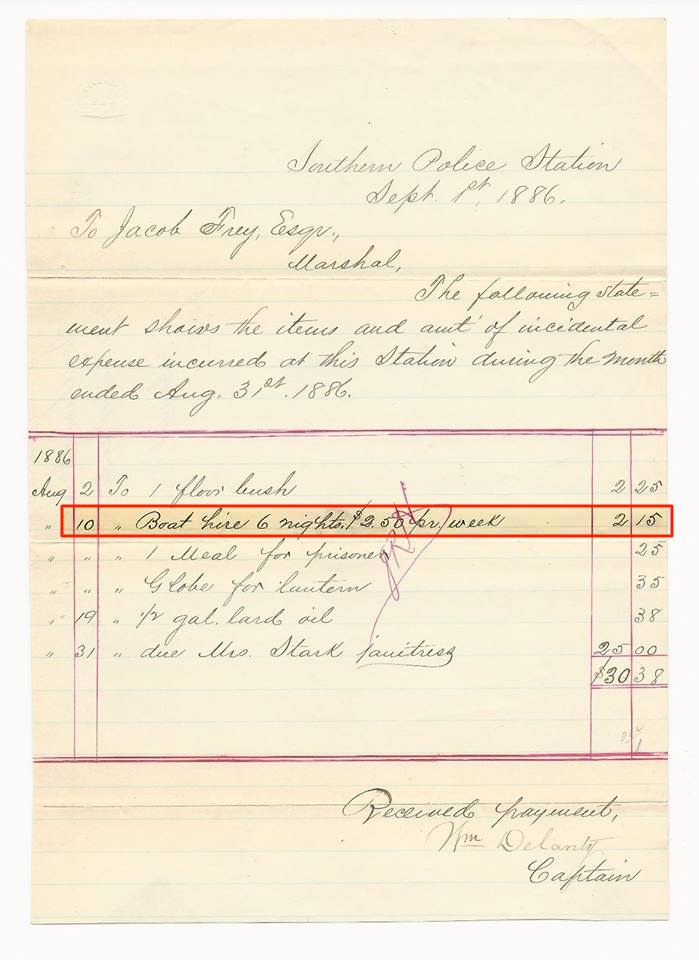

Police officers on rowboats are on patrol as the police cars move forward. Marshall Frey, operating as directed by the police board, has set up a unique police protection system for the Baltimore harbor. Twelve police officers and four flat-bottomed boats are currently working for him. Each boat will have three police officers attached to it, and each boat will have two pairs of oars so that two men can pull if there is a chase. A dim lantern will also be supplied for each boat. The police officer chosen for this task was chosen from among those with the most familiarity with the harbor and its immediate surroundings. To have three of the four boats in the Eastern District, one in the Central District, and one in the Southern District. The boats will go on duty at night and work till dawn.

According to Police Board President Colton, starting this experiment was the best course of action the board could do given the situation. without the necessary enactment of relevant law. The board was unable to activate a normal steam patrol boat. He had requested a police boat during the previous session of the legislature, but they refused. The expense of the current trial will be minimal because boats may be rented out for a few dollars per night. There is a good reason to think that it will succeed.

A steam launch is unquestionably the greatest way to patrol the harbor, according to Marshall Frey, who is referring to police security of the harbor. Although he was unable to say with certainty what kind of boat would be best, he had the opinion that it should be constructed with all the amenities required for the service. He estimated that a decent compliment would be roughly 25 men. He said that the current experiment would be a wonderful step toward port protection and that nothing more could be done until the legislature's next meeting, when the request for a police boat will be reiterated.

All of the polls have been set up in their proper locations, and the wires have been run, making the preparations for the introduction of the patrol wagon system practically complete. The new wagon for the southern area is ready, therefore the boxes will likely be placed in position the following week. Mr. John F. Bunter of Baltimore constructed it. Although it has a few upgrades, it is somewhat similar to the wagon utilized in the Central District. The wagon's body is 7 feet long. There is a small apartment to the left that the stretcher can fit into with no problem at all. In case of necessity, heavy weapons can be stored in the comparable apartment to the right. Steps in the back lead to the entryway. Each step is completed and made of brass. The wagon's body is painted in a dark color. Carmine wheels with yellow borders are used. One horse will pull the wagon. The effort to improve the system in the Eastern District is likewise moving quite quickly.

The Harbor Patrol

Reported for the Baltimore Sun - The Sun (1837-1987); Aug 7, 1886; -pg. 6

Sites are revealed by the dim lantern during a ride in one of the police boats. How about Your Light? A dark lantern flashed after the words, creating a halo of light around the head of a man of color who was scuttling a boat at night toward a fleet of Bay vessels that were ahead and facing Henderson's pier.

"Boss, I just took somebody to the coast," the shocked man said, winking and blanking in dread of the questioner who was not there. The man covered his eyes and attempted to block out the lantern's glare, but each attempt was met with the dazzling light in front of him.

Three cops were visible to the terrified individual in one of the Eastern District's port patrol boats after a brief burst of light was cut off. Sheets were put in the Stearns for a Sun reporter who was serving as the cutter's temporary coxswain. After explaining to the Charon why he was being challenged, he was given permission to leave and was ecstatic.

An intriguing aspect of the branch of police work recently established by Marshall Frey for the protection of property on wharves and on ships is a cruise with a port patrol. Hence, there are boats on duty every night, each with three officers who have been chosen based on their prior familiarity with the harbor and boat operating skills. Four boats make up the division of the work. The central crew begins its patrol with the Steamboat Peer at the southernmost point of Light Street Wharf, then moves to the north side of the basin and ends at the drawbridge. From there, the Eastern District's number one crew begins patrolling and moves on to Henderson's wharf, where the number two crew picks up the task and carries it out to the Lazaretto light. The southern district and Capt. Delanty's crew control the shipyards, coal wharves, and steamer piers all the way to Fort McHenry on the south side of the harbor.

Capt. Auid chose two attractive cutters that were formerly part of Mr. T. Harrison Garrett's yacht Gleam with the foresight that comes from experience with ships and boats. Due to their small weight and ease of movement through the water, they are especially well suited for the job. Two officers pull, and a third officer caters to the filler, bundles the light, or provides guidance. There is an established order and regularity system. To prevent confusion, each guy has been given a specific responsibility for the boat or his charge over a piece of equipment.

The patrol boat that watches over the Canton Hallow on the night in question was delighted by the change from the smooth water that predominated beneath the ice of wharves and ships further up. However, the strong southerly breeze that night made the harbor a little lumpy, causing the motion of the patrol boat to leap and jump over the waves.

Polls that were strong and durable sliced or skimmed over the water like a recently formed shell. Some of the unforeseen events during the journey were downright absurd. A wharf suddenly approached the ship's stern and began to inspect it. The dark lantern quickly indicated that the officer in the bow was alert, and when the lantern was used to illuminate the pier, two lovers were politely taken aback. Romeo himself appeared to be very perplexed as the head that had been resting on his shoulder suddenly sprang up straight as if it had never known any other position. After the lantern's light was turned on, everything in the boat and on the dock went back to being pitch-black. Perhaps this is when the old, old narrative was once again recounted while being observed by the waves gurgling beneath the pier.

Passing through silent, empty wharves and warehouses, under the sterns of large ships loading for C, and almost brushing the bow of some small craft then up and into the shadowed pier, looking beneath peers; finally, chasing after a boat with a lone person to see out what he was doing: The little boat met softly and quickly with the Lazaretto, which is marked by two red lights and delineates the area where the police patrol will go after passing steamers, banks, ships, factories, and furnaces.

The city lights could be seen off in the distance, and the regularity of the gas lamps, which resembled a procession of torches, revealed the street's boundaries. The only sounds coming from the water were the waves crashing against the seawall or a late tug returning to its starting place. The crew occasionally took a break on their oars and drifted with the current, or they paused to scan what appeared to be a boat.

The patrol's responsibilities are extensive. Before boarding a vessel, crew members are advised to lock all doors and to keep an eye out for any property that may be lying around on the decks. The patrol is now familiar with every rowboat and sailboat. They are aware of its ownership and connection points. His absence prompts a search, and its location is established. The patrol's path is determined by the situation, but every hour, the entire beat is twice covered. Vessels that arrived during the day are found and informed of my responsibility to keep a lookout prior to the general cruise.

The other night, a case study of the ship's master's negligence was presented. Through the schooner cabin's open door, a light could be seen at what seemed like an odd hour. The patrol stopped the ship as it approached on all sides. After several minutes of silence, no one spoke until the oars had struck the cabin, at which point a guy swiftly entered the companionway, rubbing the sleep from his eyes. He was informed that he might receive an invitation from seeds, so he closed his cabin out of prudence. The officer remarked that chloroform would not be necessary if all Mariners slept like that man and his crew did.

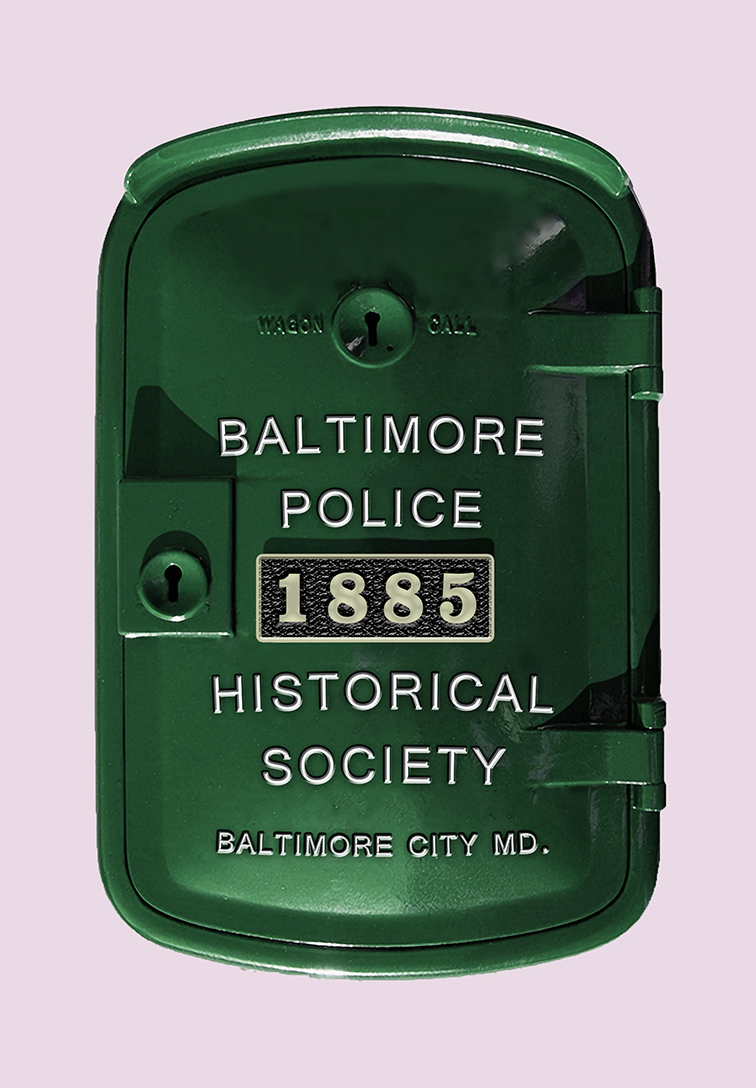

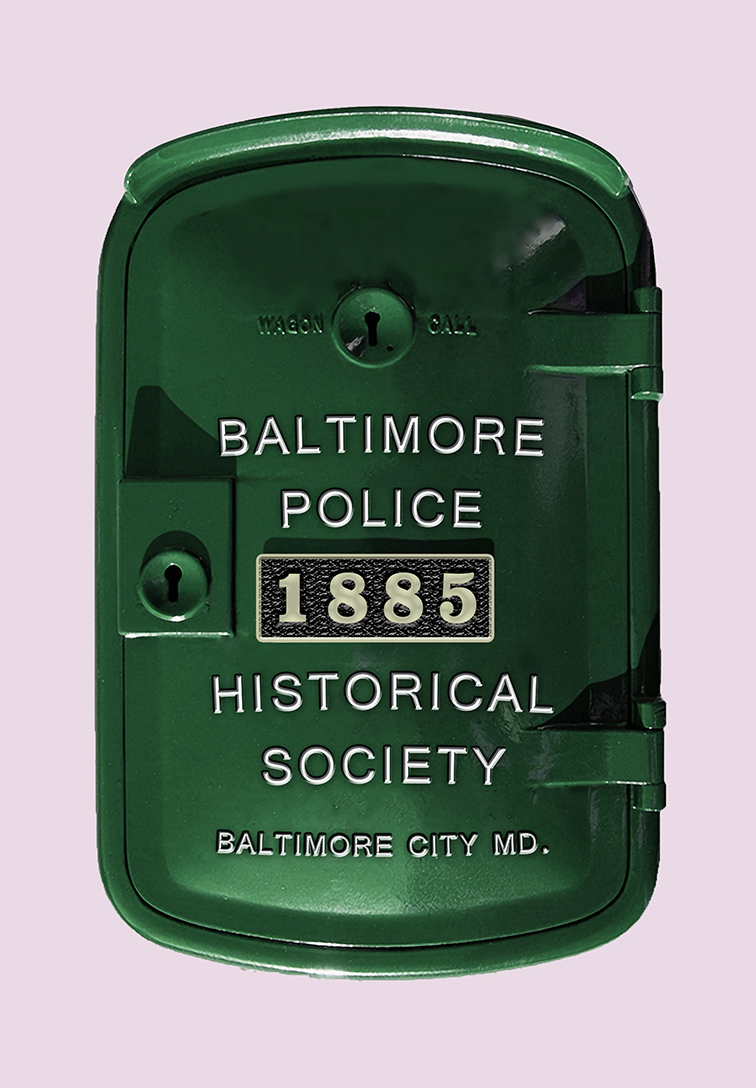

Police Call Box

Saturday (16 October 1885) Box 63 was the 1st used

It was located at the corner of Franklin and Charles Streets

History

Based on the following Baltimore got its first Call Box in 1885

After Chicago, Baltimore is thought to have been the second city in the nation to deploy patrol wagons when its first one entered service on October 25, 1885. Marshal Jacob Frey read an illustrated magazine in the gymnasium of Central's station and came across information on police patrol wagons being deployed for the first time in Chicago. The Board of Commissioners (BOC) expressed a passing interest when he presented the concept to them. Frey didn't give up on issues he was passionate about; a few weeks later, he brought the issue back to the board's attention; they had previously forgotten about it but had made a commitment to look into it. In Frey's opinion, the Police Telegraph Box System and the Wagon represented the future of law enforcement, therefore when the BOC did nothing, Marshal Frey acted on its own. He dispatched a department employee to Chicago to observe the operation of the "New Fanged" patrol wagons. According to an old record, "they were charmed." They observed Chicago's brand-new "Police Telegraph Box" system while there (Known now as the Call Box). Both of these instruments arrived in Baltimore by the fall of 1885 as a result of Baltimore's journey. Baltimore became the second department in the nation to employ the Police Telegraph System after Chicago, according to accounts in the Baltimore Sun newspaper. From 1885 until 1985, when Baltimore established a 1-800 number for police to use to phone back into the station when radio use was improper, these boxes were still in use there. By 1987, all boxes had been retired from service.

Ad for the National Telephone Company's "Glasgow Style Police Signal Box System" from 1894. In Albany, New York, the first police telephone was set up in 1877, one year after Alexander Graham Bell created the technology. First police call boxes for public usage were installed in Washington, DC in 1883. Chicago, Detroit, and Boston then installed police call boxes in 1884 and 1885, respectively. They were direct-dial telephones that were mounted on a post and frequently required a key or the breaking of a glass door. In Chicago, the telephones could only be used by the police, but the telephone boxes also had a dial that the general people could use to signal eleven different alarms, including "Police Wagon Needed," "Thieves," "Forgers," "Murder," "Accident," "Fire," and "Drunkard."

In Glasgow, England, the first police telephones for the general public were installed in 1891. Large gas lanterns were mounted on the roof of these tall, hexagonal, cast-iron boxes that were painted red and had a system that allowed the central police station to light the lanterns to indicate to nearby police officers to call the station for instructions.

Sunderland and Newcastle both used rectangular wooden police boxes in 1923 and 1925, respectively. Between 1928 and 1937, the Metropolitan Police (Met) deployed police boxes across London, and Gilbert MacKenzie Trench's 1929 design for the Met is now widely recognized. [6] [7] The original MacKenzie Trench designs state that the material for the box's shell is "concrete," with only the door being made of wood, despite some sources (such as) asserting that the initial boxes were constructed of wood (specifically, "teak"). The concrete boxes were exceedingly cold, the police officers remarked. The inside of the boxes often included a stool, a table, brushes and dusters, a fire extinguisher, and a tiny electric heater for use by the police. The London police boxes, like the Glaswegian boxes from the 19th century, had a light at the top of each box that would flash to alert police officers to call the station. At this point, the lights were powered by electricity.

There were 685 police boxes on London's streets by the year 1953. Until the introduction of personal radios in 1969–1970, police boxes were a vital part of police activity but were gradually phased out. There are now very few police boxes in Britain because their primary use was replaced by the development of portable telecommunications devices like the walkie-talkie. High Street coffee shops have been created in a few of them. These are typical in Edinburgh, but the city also contains dozens more uninhabited structures, the most of which are in varying degrees of deterioration.

The boxes in Edinburgh were designed by Ebenezer James MacRae, who was motivated by the city's wealth of neoclassical buildings. They are relatively large and have a rectangular layout. There were 86 of them distributed across the city during its height. Lothian and Borders Police sold a further 22 in 2012, leaving them with 20. Local police continue to operate one police box in the Leicestershire community of Newtown Linford.

Seen at the Glasgow Museum of Transport is the red police box. The remaining Glasgow police boxes were scrapped in 1994 by Strathclyde Police. Nonetheless, several police boxes were saved and are still standing today as a part of Glasgow's architectural legacy because to the involvement of the Civil Defense & Emergency Service Preservation Trust and the Glasgow Building Protection Trust. There are still at least four, including one in the corner of Cathedral Square, one on Great Western Road (at the intersection of Byres Road), and three others on Buchanan Street (at the intersection of Royal Bank Place), Wilson Street, and Glassford Street (at the corner of Castle Street, also recently restored). The Glasgow Museum of Transport also kept a red police box, however the Glasgow City Council determined it did not go with the new Transport Museum, therefore it was given back to the Civil Defense Trust. Glasgow's police boxes on Great Western Road are leased as a coffee and donut stand, the "Tartan Tardis" in Cathedral Square sells Scottish souvenirs, and an ice cream shop with Glasgow roots is currently operating on Buchanan Street under a license. The Civil Defense & Emergency Service Preservation Trust has put limitations in place as of November 2011 to ban external box modifications that go beyond the patented design.

Eleven of the final "Gilbert Mackenzie Trench" Police Signal Boxes in the UK are presently under the management of the Civil Defense & Emergency Service Preservation Trust on behalf of a private collector. The National Tramway Museum in Crich, Derbyshire, has a second blue police box that is kept in this design. Outside the Chatham, Kent, Kent Police Museum and the Grampian Transport Museum are boxes belonging to the Trust. On the grounds of the Metropolitan Police College (Peel Centre) in Hendon, there is an authentic MacKenzie Trench box. Although there is no public access, a Northern Line tube train traveling from Colindale to Hendon Central may plainly view it (on the left-hand side).

There are now eight Grade II listed police "call posts" in the City of London that are not in use. The City of London Police used rectangular cast iron posts instead of full-sized boxes since the streets are too narrow for them. A first aid kit was kept in a secured box, while another compartment held the phone.

In the "Square Mile," fifty posts were put in place starting in 1907; they were in use until 1988.

A new police box with CCTV cameras and a phone to call the police, modeled after the Mackenzie Trench, was unveiled outside London's Earl's Court tube station on Thursday, April 18, 1996. When London's phone numbers were changed in April 2000, the telephone stopped working, but the box remained even though money for its upkeep and maintenance had long since run out. The renovation and upkeep of the box, which is now somewhat of a tourist attraction because to the Doctor Who association (see below), were once again funded by the Metropolitan Police in March 2005. In 2005, Glasgow unveiled a new style of police box. The new boxes connect callers to a police CCTV control center operator through digital kiosks rather than booths. They have a chrome finish, are 10 feet tall, and have three displays that display information about crime prevention, police force recruitment, and even tourism attractions. Similar to Glasgow, Manchester features "Help Points" that are equipped with sirens that sound when the emergency button is depressed. The siren also draws the attention of neighboring CCTV cameras to the Help Point. Police "Help Points," which are essentially an intercom box with a push-button positioned below a CCTV camera on a post with a direct line to the police, are buildings that resemble police boxes and are located in Liverpool.

Currently on loan to the BPD Museum

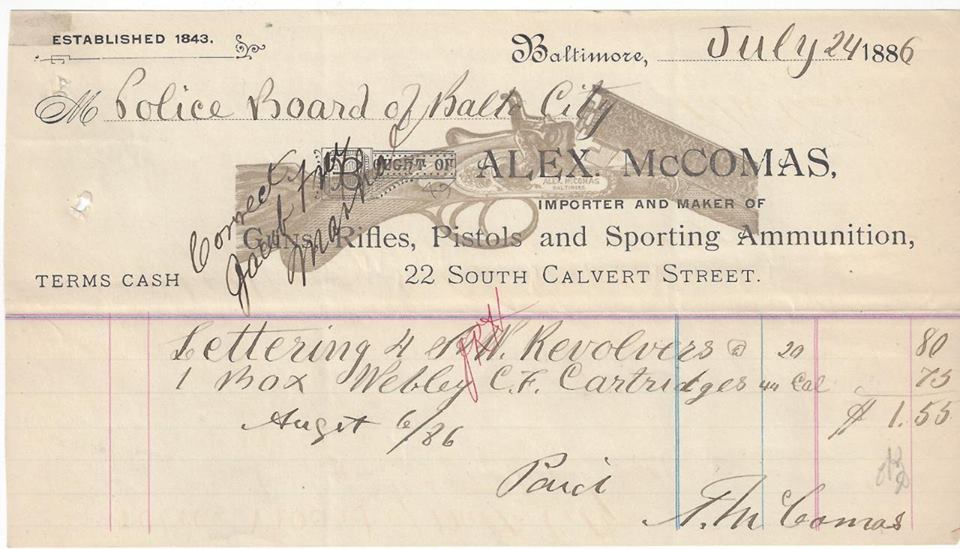

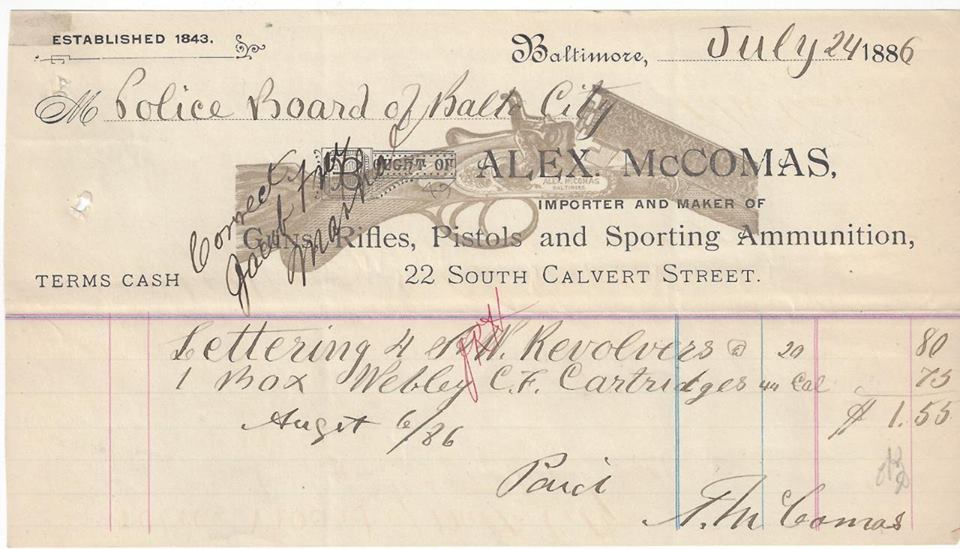

It shows where Marshal Frey ordered some engraving's on our pistols circa 1886

This shows where Marshal Frey rented a rowboat for the Southern District 1886

This is a pic of Marshal Frey's watch and what follows are various shots from various angles