There were chiefs, and there were chiefs. Some chiefs had become chief, chiefly by virtue of enormous and helpful political pull. Some have become chiefs merely because fortune happened to be in a sunny humor one day and blew a feather of leadership on their caps.

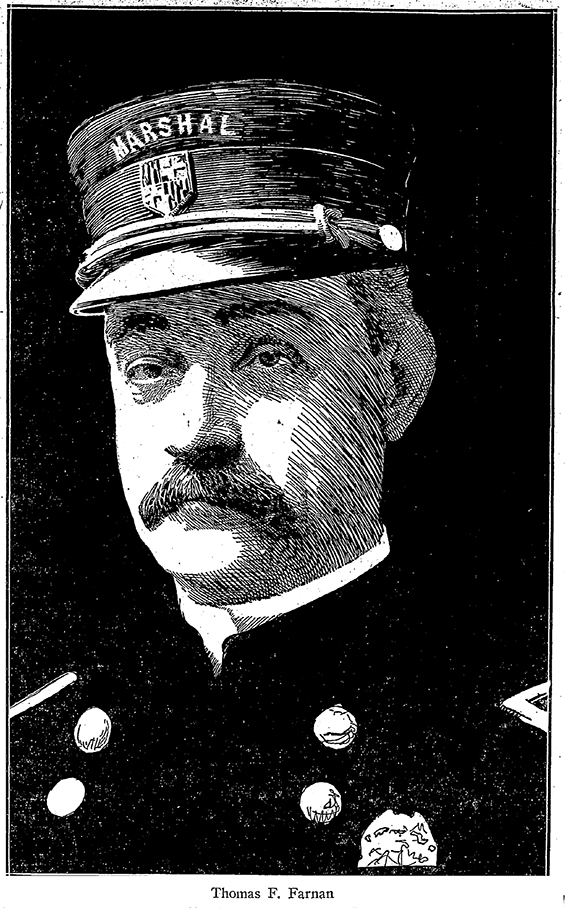

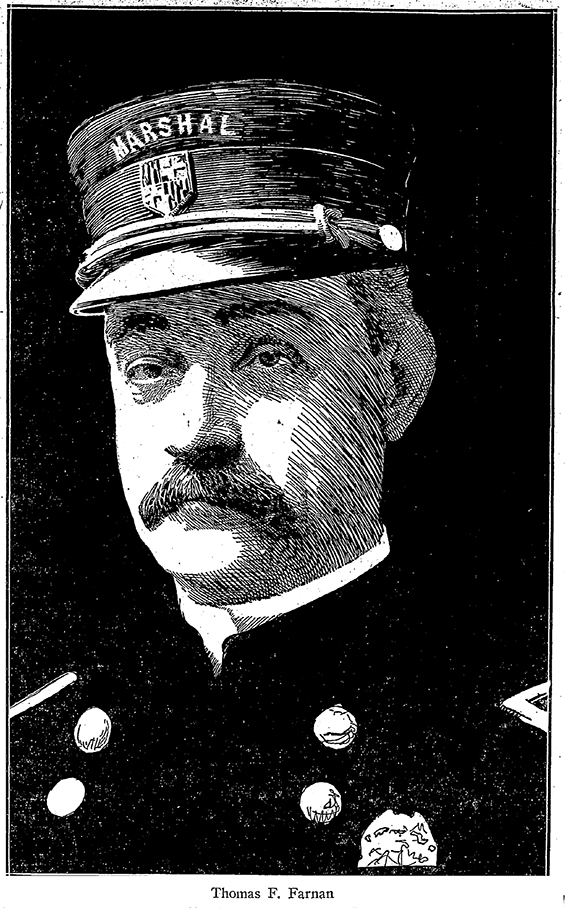

The Grand Master of Baltimore Police

Marshal Thomas "Tom" Farnan

Real Police

The Grand Master of Baltimore Cops

Marshal "Tom" Farnan

Newspapers of the Times; 10 October, 1909 Tom Farnan, Marshal of police of Baltimore, was one of the greatest police chiefs in the country, and his record was one that could hardly be equaled.

There were chiefs, and there were chiefs. Some chiefs had become chief, chiefly by virtue of enormous and helpful political pole. Some have become chiefs merely because Fortune happened to be in a sunny humor one day and blew a feather of leadership on their caps.

Marshal Farnan became chief his own right, because he has seen two score years a practical service without a single lapse of duty, because he has been through all the knotty experiences that the men under him have to go through, because there is no windy beat or troublesome post so windy or so troublesome that his own experience couldn’t bring forth suggestions to help those under him who must tackle it. He knew his job, and his job fit him like an old shoe.

There was no fuss or hurry, or glitter in Marshal Farnan’s office in the courthouse. He was a thoroughly work-a-day atmosphere. There are no hidden private rooms, or solemn ante-rooms, with bell boys hopping from one to another. There was no painfully obvious, and rigid system. Everything ran as smoothly, and quietly as a Swiss clock that was among the best ever made.

His Daily Routine

When Marshal Farnan came down to work every morning at 8:00 prompt, he first opened his mail, and dictated his replies to his ever ready, vigilant and hyper-excellent secretary; John Swikert, the reformed actor. The replies to communications from departments in other cities he dictated right away. If there is no special hurry for a response he saves the letter until later in the day and turns his attention to the next matter on his docket, which was his daily reception to the police captains.

Every morning the captains from all the districts in the city make their way to the Marshal’s office and about 9 or 9:30 o’clock. That explained to the people in the area of those times why it was that you would see magnificent apparitions of gold lace, and blue on the downtown streets in the early morning.

They head toward the courthouse like Kingfishers – or whenever that Gaudy painted, Shameless bird is – after snakes. Once within the sacred precincts of the Marshal’s office they salute, and clear their throats and then sit down, and bring forth their daily written reports.

First off, the Marshal looks over these reports. Many get ready for the regular morning captain’s pow-wow… or big talk

A Secret Conclave

The rest of this and description must be written from imagination, for that meeting was held behind closed doors, and the reader may assist in the next paragraph or two, if he or she pleases, by as many poetic and affecting thoughts from his or her imagination as they like.

After the vulgar mob has been excluded Marshal Farnan harangues his Captains and asked them for confidential tidings regarding affairs within each of their perspective districts. They told him all that was going on – who was selling on Sunday, what old offenders have bobbed up, what hand-books have been reported, how many dogs are howling at night and how many husbands were beating their wives. Marshal Farnan hears them in silence and then gives his opinion. He asks his chiefs their opinions, too, and every morning, in fact, there is a formal council of war. If there is a big case on hand the conference may last until after noon.

The deliberations of this august body are never made public. They never find their way to any record except as the secret spring of a capture or trial. The findings of the counsel were simply repeated by the captains to their lieutenants and the men under them, who were supposed to carry out orders.

Many tails are told before this gathering. Some more pathetic, some more humorous, some more tragic, some more Serio-comic, and some nearly sordid, and more pitiful. All of them were filled with human nature at its rankest. There was material enough for volumes of equally rank novels, magazine stories, or theatrical plays in these incidents of real life, yet any one of them would flavor a Henry James book for 20 chapters, or 20 years.

Many Tales of Woe

So accustomed has good a Marshal “Tom” grown to such tales, however, that he does not think about their more appealing side. His sympathies are not hardened, and he is not apathetic, and the stories he hears would stir him to tears sometime if he allowed himself to think about them. But he looks at them only as problems of police work that he has to solve, and as such he did not allow himself to become excited.

At the conclusion of his captain’s meeting Marshal Farnan and finishes as much mail as he can and began and receiving callers. There are continued calls upon him and upon his patients. Men and women come to him with the most absurd complaints.

For instance, last week an unshorn individual who claimed that he hailed from Washington materialized himself before the Marshal’s desk. The Marshal look at him and said, “Good morning,” pleasantly. “I want you to find my boy,” said the unshorn individual. – “I waited two days for you to find my boy!

“Who is your boy?” asked the Marshal with a patience born out of long experience.

“I sent you a letter about him two days ago” said the ever-weary stranger gruffly. “I live in Washington” – “What makes you think that your boy came to Baltimore.” asked the Marshal softly

“He didn’t have money enough to go farther away,” said the stranger in a final tone, “He is here.”

Then the Stranger Faded

"Did you ever stop to consider that your son might have jumped a freight train and gone further away!” asked the Marshal. “If you have good cause to believe your son came here, and is still here, I will have our police search the city once more, but we can’t waste valuable time, in following foolish clues.”

It was at this point that the stranger went, and peace brooded once more over the northeast corner of the Courthouse.

The principle offenders in the way of butting-in were women, however, it must be hastily and firmly noted. They have the excuse that they didn’t know much about police procedures of the times.

Their inquiries and subtleties were very, very trying. No immediate specific instances came to mind, because examples of such a kind are so frequent that they were not noted when they occurred, but it is not infrequent for a woman to ask for the personal assistance of the Marshal of the Baltimore Police Department to find a stray pet poodle.

At about 12:00o’clock Marshal Farnan goes out to lunch. He places a tall black derby hat above his cadaverous and melancholy countenance, dons a long coat of a somber hue and slides out of his office.

He lunches at his home, out on West Lombard Street, near the corner of Fremont, and he returned to work at about half after 1 o’clock. Then the afternoon from that time until 4 o’clock is taken up with hearing complaints of various sorts or in personnel excursions to different points in the city, and in answering letters.

At 4 o’clock he goes home once more and stays there and still his return to the office at 6. There he retains, finally until 8 o’clock, when he strolls out of the office, and if that night is fine walks home, content that one more day’s work has been dispatched.

Something Like Old Abe

It takes a peculiar talent to handle nicely the problems that arise in the Marshal’s office in a great city, but Marshal Farnan has the gift. To be a good chief of police, you must be wise and moderate, firm and harsh, kind, severe, lax, strict or stringent, pleasant and unpleasant, as occasion demands. And above all, you must have a sense of humor and a sense of proportion. If you have not this sense of proportion in a position so filled with bother some little details, you are lost, indeed. Marshal “Tom,” like Abraham Lincoln; has a sense of humor. If we look at his photos we’ll notice, the resemblance between Tom Farnan, and Abe Lincoln in many respects? Tom Farnan loves jokes, jokes of all kinds, big, broad jokes and little ladylike jokes, and he prefers big, broad that man’s size to jokes best of all. - Farnan He was always ready to swap a joke at the proper time, and he had a melancholy and humorous countenance. Beyond that he never lost his head during an emergency.

There were indeed, many characteristics in their separate makeup as in their separate, and divergent spheres, wherein the martyred president, and the living and healthy terror to evildoers of Baltimore might meet and shake hands.

When dealing with the big situations Marshal Farnan was always calm, cool, and collected. He did not act hurriedly, though he handled matters promptly and boldly.

Marshal “Tom” simply dotes on a good, rattling, puzzling, sleuthing job that calls all of his wits into play. This side of his nature is shown very well in the fact that when he was on the force as a common, garden variety member of Baltimore’s “finest” he was especially fond of burglary cases. He solicited, sought out and made up all manner of burglary cases just for the pleasure of working the case up.

Now, a burglary case, to an ordinary policeman, is a nuisance. He doesn’t know how to handle it. It requires a deep thought and much diplomacy and a natural knack for untangling, somebody else’s tangles.

A Specialist in Burglars

Marshal “Tom” used to specialize in burglary cases. The more tangled they were, the better he liked them. He made himself famous for a number of clever captures he effected among the gentleman of the jimmy and dark lantern, and he is on record as having unearthed burglary cases where burglary cases would never in any sane world be able to grow.

He liked the burglars. He may have caught more burglars then there were burgers, but at any rate he caught all that there were in his district.

Then another quality besides this one of patience and persistence that helped to make Marshal Farnan a good police officer, was his ability to pick out the salient one amidst a mass of clues and run that one down. He was practical with common-sense, and he had worked among men so long that he is able to perceive by a process of divination how a man would act under given circumstances.

In the office Marshal Farnan is silent with his mere acquaintances; approachable, but taciturn, with those who have not yet made his acquaintance, and affable and even jovial with his friends. After hour, or when there is a slackness in the rush of things at the office, he was laughing, good humored, boisterous sometimes, and they all together a good fellow.

Every real man of the time had some characteristic that at distinguishes him from the Sunday school pictures of the perfect citizen. It was these kinds of things by which you had to add them up in your memories storehouse.

Sometimes He Explodes

Marshal Farnan’s unscriptural characteristics is a Celtic an exceedingly hot temper that if once allowed to get out of bounds rampages around in a very the lively matter until it cools off, which happens very shortly. It is not often that the Marshal gets fighting mad, but when he does he is red-hot. The object of his wrath goes to a cyclone cellar or picks up his remains and escapes.

Cursing, screaming, swearing, yelling, blaspheming, cursing, cursing, and still more cursing “It was one of the Marshal’s off days.” Addy-Kong’s and mere assistants of all sorts scamper out into the marble corridor like leaves blowing by a frosty autumn wind. But they don’t come often these spells of wrath, and they clear away shortly and politely.

“Marshal Farnan is one of the most pleasant men in the world to work for” said John Swikert, his time-tried secretary, last week. “He doesn’t hurry you, and he is always good tempered – unless you interfere with his work. I have been with him for years, and I wouldn’t want to work for any other man in Baltimore.” Another one of Mr. Farnan’s Office family is his deputy, Mr. Manning. Deputy Manning is almost as well-known as his chief, and his duties are almost as onerous. He has been associated with Mr. Farnan for many years, and he was a brother in blue, on the force with him for many other years. He is ready at any minute to lookout for Marshal Farnan’s and all the jobs in addition to his own, when Marshal Farnan, for any reason, is not at the office.

Last May a year ago, when Marshal Farnan had been 40 years a policeman, his official family, and many of his admirers in the city and State joined together in giving him a banquet and a silver service. The banquet and presentation came off at Hazare’s Hall and a large crowd was in attendance.

Governor Warfield was there, and Marshal Farnan made a speech. There were other speeches by various men prominent in Baltimore.

His Police Career

In presenting the service president Willis, of the police board said;

“On April 30th 1867, just 40 years ago tonight the young man, then just 21 years of age was appointed as a patrolman on the police force of Baltimore. He reported to the Southern Police Station and was assigned to duty, with the instructions to keep his post quiet. By daylight this new officer had made 25 arrests.

“On February 1, 1870, just three years later, he was promoted to the grade of Sergeant, and his rigid enforcement of discipline and as kind words of caution to his squad, some of whom are members now of the force, are well remembered and appreciated.

“On April 24, 1871, this young man was promoted to the grade of Lieutenant; on October 24, 1885, promoted to the grade of Captain on February 23, 1893, was promoted to the grade of Deputy Marshal, and on August 8, 1902, to the grade of Marshal of the Police Force of Baltimore City.

“Upon examination of records of the department there is nowhere to be found any entry indicating that this young man had ever been censured for neglect of his duty, or for the slightest violation of any of the rules of the department. During his long career, of faithful service many incidents can be pointed out where, at the risk of his own life, he had intervened for the protection of life and property, and where violators of the law had been uncovered by him. and brought to face the charges made against them.

His Record Is Clean

“Marshal Farnan occupies a most enviable position in the history of police affairs in this city. So far as can be ascertained Baltimore alone can boast one of the Chiefs who has surged 40 years in various ranks without interpretation and is still vigorous and strong. That he showed, city’s long years of experience, occupying from the lowest to the highest rank, come in contact with many exacting an exciting situations, temptations, hardships and dangers, come out of all unharmed and with a record perfectly clean, and with a reputation of having faithfully and will perform his duties, is a great record, and should excite emulation and the members of the police force.

“Marshal Farnan has a national reputation, and his good work at the head of the department has given this city the name amongst crooks as “The Graveyard” because few of the criminals who have operated in Baltimore in the past years have gotten away.

“In presenting this beautiful testimonial to you on behalf of the force and you are many friends, it is proper and that I should say that your services have not gone unrewarded. There may be cities where a man in your position commands more money than you get, but there is no man and public service anywhere in the world who was more appreciated then you among your fellow citizens, and this testimonial should be a lasting memory to you of the esteem in which you are held by your fellow citizens.

His Duet of Vices

There be way and ways of living, and when a man has lived over threescore (60) years and bids fair to complete a great deal more than threescore-and-10 (70 years old), the Psalmist’s allotment to mortals, it is a matter of interest to know how he lives.

Marshal Farnan is common sense in his mode of life. He rarely touches liquor, but if when off-duty he wants a drink he takes one, he smokes, and chews tobacco and he eats in very rapidly. These two points are about the only ones in the schedule of his personal economy that could be marked with black crosses. He smokes periodically outrageous cigars and thief fairly bolts his food.

He is fond of fresh air. He usually walks to his home out on Lombard Street if today is good, at the end of the day’s work. Whenever he can, he takes the error.

Just about two years ago Marshal Farnan attracted a good deal of attention on a gossipy way among Baltimoreans by backing the Biblical saying that it is not good for a man to live alone and by going it one better by the assertion that a man had the best begin the process of living double early. His pronunciamento [form of military rebellion] became a topic of tea tables, and café tables. There were frenzied and discussions in all parts of the city, pro and con, whether or not and why.

Marshal Farnan stuck stanchly to his guns. It was good for a man to marry early; he said, he married early himself and he had been a most exemplary family man. His wife’s name before marriage was Margaret Sicilia Applegarth, and she was the daughter of Robert Applegarth of this city.

Say what you will, the Irish blood produces many great and enviable characteristics. It produces humor, buoyancy and energy, as exemplified in Pat Kirwan, Michael Redding and in Marshal Farnan’s keen appreciation of a humorous situations comes from his Irish birth. How He Joined the Force

The main facts of Marshal Farnan’s life since he joined the police force are in President Willis’ speech on the occasion of the affair at Hazare’s Hall. His life before he became a policeman can be summed up briefly.

Thomas Frank Farnan was born in Baltimore on March 15, 1846. His father was Michael F. Farnan, a laborer, who had been frugal enough to retire from work in his old age.

Young Farnan attended the public schools of Baltimore, and later Calvert Hall, from which he was graduated in 1862. His ambition had always been to become a carpenter when he should grow to manhood. From his early boyhood days, he had played and worked with carpenters’ tools, and soon as he finished his high school he apprenticed himself out to a carpenter.

As a carpenter he labored for about four years, when a want of work in his chosen line prompted him to turn his attention to millwrighting. He was not long a millwright before another dull season found him without work.

At this time there occurred a reorganization of moment in the Baltimore police department, and several of Farnan friends found themselves positions of influence within the new board of police commissioners. It was suggested to him that while he was without work in his own trade he try his hand at being a policeman.

Farnan was at that time just 21 – the age requirement for applicants for positions as police – and he determined to permit his friends to secure for him a place. In April 1867, he was appointed as policemen.

In those days the police were not required to serve as probationers, as they are today, and the young officer was given a regular assignment, and that in one of the least desirable districts of the city. Four days of police duty in the Southern District decided the young officer that he had not been intended for a policeman. That day as he greeted the Lieutenant of the district it was with no cheerful face, and he frankly announced that he was tired of being a policeman and that he wished to put in his papers and resign.

“Hold on a little longer,” the Lieutenant advised. “You will like it better after a while.” Young Farnan, yielded his advice and held on.

His First Big Case

One of the first cases Marshal Farnan ever figured in was that of George Woods, alias George Moore, in Negro who was a desperate thief. Woods came as his first big case, and for that reason and the arrest is still green in the memory of the Marshal.

It was on the night of January 7, 1869, that he made the arrests, after having worked on the matter for nearly a year. Captain Wallace Clayton, of this daughter Brittany, lying at the bowery wharf was one night robbed and the thieves cut out one of his eyes when the captain tried to fight for his life, the case aroused a great deal of indignation, and though the thieves left no clues behind, young Patrolman Farnan worked steadily to unearth the crime.

Finally, he struck the trail, and captured Woods. Captain Clayton identified him as his assailant, and Woods went to the Maryland penitentiary for 15 years. One of the most eventful periods of the Marshal’s life was during the railroad riots of 1877. He was a Lieutenant in the Southern Districts working under Captain Delanty at the time and was in charge of a squad of men at Camden Junction Station. When the fifth regiment arrived at the depot the mob threw stones at the soldiers and Lieutenant Farnan saw a big man serve one of the missiles.

Fought His Way Out

He grasped the man and his fellow-officers tried to persuade him not to fight his way through the mob with the prisoner. Lieutenant Farnan said, “I’ve arrested this man, and I intend to take him to the Southern District Police Station!”

He started with his prisoner, and the mob made to rush for him. Women called from the windows to the officer to take refuge indoors to keep from being killed, but he shook their advice off, and continued about his path.

In a short time, things became so heated, the Lieutenant saw no other choice but to go to the extreme to impress upon the crowd his determination in leaving the area and leaving it with his prisoner I tow.

With this he withdrew his pistol, placed it against his prisoner’s forehead, right at his temple, leaned in and calmly told him, “If you do not tell this mob, you are willing to go to the police station with me, I am going to blow your brain out of your head, and into the crowd!” The prisoner recognizing something in Farnan’s tone that let him know, Farnan wasn’t bluffing. The prisoner became thoroughly frightened, and began yelling to the crowd, “Stand down, stand down, I wish to accompany this officer freely and of my own will!”

With that the mob withdrew their advances on the Lieutenant, making Farnan one of the first policeman to go into the mob and come out with a prisoner.

His presence of mind, and ready with saved him upon that occasion, as it has many times since. But those things are past now, and as he looks back on them the Marshal laughs heartily, as though they were all big jokes.

He is particularly fond of telling these war stories in which he was the butt of the joke, but he also knows a good many in which he figures as the joker, for the Marshall is full of fun.

A Frenzied Irishman

He tells with great delight of a case which occurred while he was Lieutenant in the Southern District

“There was a lot of excitement down there one day,” he says, “and it was all caused by a little Irishmen. He raised such a racket about his house that the neighbors complained, and a minister declared he could not conduct his services. I went around to the house, and there stood and probably 800 persons listening to that curses, and shrieks of the man. Some officers stood outside, and I ask why they did not go in and arrest the man.

“Why, he has a pistol and told us he would kill the first man who comes near the door,” they said.

“I asked who he had the warrant,” for I knew one had been issued in the case, and when it was given me I called to the man inside, asking if he heard me.

“Yes, I hear you,” he said, and I’ll blow the top of your head off if you come near me”

“I read the wanted him and then told him to open the door. He refused and repeated his threat that he would kill the first man who tried to enter his house.

“I put my shoulder against the door, and it went in with a crash. I stepped into the room, holding a lantern in one hand, which had been provided by a woman who live nearby, my pistol was in the other, and I started to the part of the house that we had sensed he was staying. As I rounded the corner from the hallway to the great-room, there stood the little Irishman, he was in the middle of the room, we quickly locked eyes, and as I was bringing my pistol up on target he said: “Why, Mister Farnan, how do you do? If I’d known, it was you I’d have opened the door long ago!”

He Caught a Tartar

One night when the Marshal was still a Sergeant he met a young Negro who was deaf and dumb. The man was powerfully built and had already committed an assault. Sergeant Farnan placed him under arrest. The Negro wheeled about, catching the Sergeant’s arm, and threw him over his shoulders as he were handling an infant.

The Sergeant was at the man’s mercy, because both his hands were helpless, and he could not use his feet. Holding his prisoners tightly as he could and without apparent effort, the negro climbed up the stairs of a house in the neighborhood until he reached the buildings attic.

There the Sergeant found himself face to face with three other negroes, all of bad reputation. Realizing his position, the Sergeant told the trio if they did not help him place his deaf-and-dumb prisoner under arrest he would hound every one of them, (assuming he himself made it out alive.)

The officer was an earnest, and his tone once again conveyed honesty which could not be mistaken. With that all the men knew they had better take sides with him. The four of them joined forces in grappling with the suspect, the five men would all tumble down the steps to gather. This struggle on the staircase was more than the old wood can stand and it gave way.

Sergeant Farnan knew it was the encounter of his life. As soon as the mass of humanity of which he was part, reached the sidewalk he rapped on the curb with his Espantoon. Other policeman hearing a call for help, came to his aid.

It required eight of the “finest” to land and suspect in restraints and get him down to the station house.

How He Was Called Down

There has been much made of the fact that Marshal Farnan has never been reprimanded in his official career. He has not, but he has been severely repulsed as the following anecdote will show.

There was a great throng in front of the Cathedral during the recent Cathedral centenary. The marshal had policemen of all grades there to see that order was preserved and he went up to look about for himself. He saw a little group standing in the way, so he walked over and asked that the group stand back.

“Oh! go on, Tom Farnan, and don’t get smart; for we’ve got more right here then you have!” Said a typical old Irish woman, as her eyes snapped fire at the Marshal.

If the Marshal is a fighter, he displayed none of this ability there but moved off without another word. Later he told it as a good joke on himself.

Marshal Farnan knows everyone worth knowing in Baltimore, from Cardinal Gibbons down the line. When he can get away from his office for a few hours he likes to move about the city and talk to the people. As a rule, Deputy Marshal Manning is with him and often they are seen at the theatres in the evening. When he was a couple of days off the Marshal goes to West Virginia to visit his married daughter

FINGER PRINTS TAKEN

Taken from the News of the Times; Nov 27, 1904

New system of identifying prisoners used for first time

The new fingerprint system of identification was officially used for the first time at the local Bureau of identification yesterday, (Saturday, 26 November 1904) the subject being John Randles, colored, who was committed to jail for court on the charge of larceny and has a criminal record.

Randall was very nervous while the Sgt. Casey was taking the impression of his thumb and fingers and begged the officer not to hurt him. He appeared much relieved when the operation was over, and greatly pleased that he had felt no pain. The impressions are taken by pressing the thumb and fingers on a piece of glass, thinly coded with printer’s ink, and then pressing them on a piece of white paper.

The Baltimore Police Department recently adopted the fingerprint system of identification as an adjunct to the Bertillon system of measurements, and Sgt. Casey, chief of the local Bureau, was sent to St. Louis to study the new system under Detective Ferrier, who has charge of the Scotland Yard exhibit in the Royal British Pavilion at the Louisiana Purchase exposition.

3 Jan 1905 in an article entitled: 187 Photographed and Measured - The article gave an inauguration date of 7 Dec 1904, for the start of the finger-print system in the following article:

HIS BRAVERY RECOGNIZED

Taken from the News of the Times; Jan 3, 1905

187 Photographed and Measured

The annual report of Sergeant John a Casey, Chief of the local Bureau of Identification, and his assistant, Sergeant Higgins, shows that during the year that just ended 187 prisoners have been photographed and measured according to the Bertillon system. The finger print system of identification was inaugurated (Wednesday) 7 December last (1904) and since then 25 imprints have been taken. The scenes of six murders were photographed, as were also four unidentified dead men. Photographs and records to the number of 338 were sent to other police departments and 217 photographs and records were received.

BERTILLON IS MODEST

Taken from the News of the Times; Nov 8, 1905

BERTILLON IS MODEST

Gives Credit to the English For Some of His Work.

HIS FINGER-FRINT SYSTEM

Thinks all the criminals in the World Will Ultimately Be identified.

“I learned the foundation of my fingerprint knowledge from the English.”

This striking and at the same time characteristically modest utterance was made in an interview by Mr. Alphonse Bertillon, the great French anthropometrical and expert, the man whose name is closely associated the world over with the identification of criminals by measurements and fingerprints.

Mr. Bertillon was fresh from the witness box at Bow Street, where he had been giving some of his deadly fingerprint evidence with regard to the recent ghastly crop of Paris murders.

In appearance M. Bertillon is the serene thinker rather than the man of action, the scientist of the cloister rather than the public figure of the forum. To talk with him is to see that he has thought out the fingerprint system bit by bit, arched by arts, loop by loop, and whorl by whorl, even as he is sought out the science of anthropometry millimeter by millimeter.

A high four head, a well-balanced brow, a thin, oval face, a pair of serene dark eyes, a dark mustache, obviously French, but not to pronounced in curl; a trim, dark beard, a complexion strongly reminiscent of parchment. Long and delicate fingers, a tallest and latest frame, and the ribbon of the Legion of honor almost imperceptible on the lapel of his coat; such in brief is M. Alfonse Bertillon, the terror of criminals.

“Do you think, M. Bertillon,” I asked him, “that the science of measurements whatever supplant the science of fingerprints?”

“No,” he answered very quietly. “I think the human measurement system will supplement and assist the fingerprint system in the ultimate marking down and tabulating of practically every known or potential criminal in the civilized world. The sister science will go hand in hand. The science that is based upon the fact that each different individual has among his bones certain characteristic shapes and dimensions will march forward in unison with the science each arises from the circumstance that the fingerprints of practically everybody are different from the fingerprints of everybody else. Both these truths and the application of them in every day criminal search and detection have been of enormous service to us in France, and it helped to read respectable society of many of the human harpies who prey upon it.”

“And what led you to take up the study and practice of fingerprint science?”

“Reading of the work of Herschel and Galton. I looked into what they were doing as pioneers of the fingerprint system. I became deeply interested. I soon found that they were right, and I started collecting fingerprints of friends and of criminals myself.

“My subsequent experience in actual criminal practice has shown me that if do fingerprints tally exactly it is practically certain that they are the Prince of one and the same person, however many of the population of the entire world may have passed that way and have handled the article on which the print has been made.”

“And the sister science to fingerprints. Your own gift to the world, the science of the measurement of man, how did you first come to think that out?”

“Well,” answered M. Bertillon, with the ghost of a smile and a tiny depreciating’s rug of the shoulder, “I saw the need for some such system for the identification of criminals. I saw that the evidence of the photograph and the official description might very easily be made useless, and indeed has in many, many cases been quite nullified by the criminals own little tricks of disguise. All the previous photographed and officially described criminals had to do was to alter the style of doing his hair and the color of it. To distort his features and one of the well-known ways, to remove or add a mustache, a beard, to alter the eyebrows or what not, and he had passed beyond the likelihood of recognition.

“But a man cannot change his bones. He cannot disguise the exact length of his nose, of his four head, then length and width of his head, and length of the left middle finger, the length of his left foot. “Experience soon taught me that these bony portions of the human frame rarely undergo any material change in the adult and that practically no two persons in the civilized world have the same combination of measurements. This great central fact, together with the marvelous faithfulness of the fingerprint record, has been of immense assistance to us in France in the detection of criminals, and the more of these records we take the more strongly is the efficiency of the two systems of fingerprinting and measurements substantiated and proven.”

Sir William Herschel, cited above by M. Bertillon as one of his teachers, took many fingerprint observations while in India and was so convinced of the efficiency of the principal that he brought it back to England a mass of evidence on the subject. This was of great value to M. Bertillon.

Mr. Francis Galton, the other English fingerprint pioneer, after long and close study of the vast number of finger prints, estimated that the chance of two sets of fingerprints being identical is less than one in 64 billion.

Thus, is the march of science going triumphantly on, to the harassing and hindering of the human pest in his malignant deeds against society and social peace and safety. By a gracious feature of the internationality of brains grants, by M. Bertillon, has learned from us, and we, by Scotland Yard, have learned from France.

To the comfort of peace loving citizens and to the terror of evildoers, be it known that there has long existed between Paris and Scotland Yard a real, deep seated entente cordiale.

FINGER PRINTS OF CROOKS ARE NOW AIDS OF POLICE

Taken from the News of the Times; Apr 21, 1907

FINGER PRINTS OF CROOKS ARE NOW AIDS OF POLICE

Baltimore, The First American City To Adopt

NEW IDENTIFICATION METHOD

Thief-catching is becoming more and more a matter of system. With every other profession it shares the tendency to method that characterizes the present century.

In the old days it used to be a free Chase in the open with no odds given, and a scrimmage at the end between the defenders of the law and its violators. But all this is passed. Criminals are now cataloged. When they are wanted the apprehension is gone about in a matter of fact, systematic manner. There is nothing left to chance.

In line with this tendency in the ancient trade is the fingerprint method of identification, invented by E. R. Henry, of Scotland Yard, London, and lately tried in Baltimore for the first time in the United States. By its means a criminal is tagged and recorded without the possibility of error. His identity, once his fingerprints have been taken, can never be disputed, and his life story, with a summary of his habits and personal characteristics, is always where it can be reached at a minute’s notice.

KEEPING TRACK OF CROOKS

For the last half century, the constant effort in police circles has been to find some means by which a criminal’s identity could be permanently fixed. The great utility of the rogue’s gallery and the system of keeping a record of all persons convicted in the upper courts has made this and evidently desirable one. But a rogue’s gallery or cabinet of biographies is of little use, it can be seen, is the identity of the law breakers is a matter of uncertainty. An alley S or the skies is easily assumed, so if there is no other way of fixing the identity of the person them by name or photograph the rogue’s gallery and criminal record might as well go to the trash pile.

To accomplish the desirable and of absolute identification various schemes have been proposed and tried. All have been based upon the principles that there are certain parts of the human body whose form cannot be changed without detection.

First came photography. This was in the days when the art was no were then now and was thought to have marvelous value. At one time, for instance, it was believed that a photograph was a sure means of telling whether or not a person was going to develop an eruptive sickness, for it was said that the irruption would show on the photograph even if it had not yet made its appearance on the sitter’s face. Despite its many real virtues, however, photography did not fully cover the ground desired.

FAILURE OF PHOTOGRAPHY

it had been supposed that a series of photographs showing a criminal in various poses – full face, half face, profile and so one – would be a complete means of identification should that criminal the Apprehended at any time after the photographs had been made. This idea was proved a fallacy, mainly through the cleverness of the criminals, who found that a contortion of the muscles of the features materially altered the value of the portrait.

Anyhow, the schema was wholly inadequate for the task it was at first supposed to perform. So many criminals looked like that in some notable cases their portraits were hardly distinguishable.

Photographs proved of such accessory value as a means of apprehension of criminals, however, that the gallery and camera were made a permanent adjunct to most police bureaus. Still something else than pictures was needed for an absolute means of identification.

The Bertillon method was the next thing of consequence to make its appearance. Much has been written about the Bertillon method, and by many criminals and criminal – takers it is regarded with a sort of superstitious veneration, its intricacies seeming a sacred rite. It has proved very effective, but is not altogether infallible, as the case that happened in London about 10 years ago suffices to show.

At that time to criminals were measured and it was found that their records were exactly the same. This is rather a marvelous coincidence and is the only one recorded in the whole history of the system. Nevertheless, it shows that it is not absolutely infallible. Other points to be urged against the Bertillon method are that it is complicated, time-consuming, and can only be applied to adult prisoners.

THE FINGERPRINT SYSTEM

Votaries claim for the latest arrival, the finger – print system, that it was known of the faults of the Bertillon method and that it has all of its virtues. This is rather a broad assertion, but to prove it they point out that the finger – print method is simple, quick, absolutely accurate and applicable to an individual of any age. They are intensely enthusiastic, but the process is rather new, and votaries of any new faith are always apt to go to the extremes.

If the capital E. Are. Henry finger – print system of identification really does pan out in practical working – and it’s test in Baltimore seems to show that it will – Paul missed will be jubilant and materially – minded of the world reproved, for the principle upon which it rests is one that fortunetellers have long banked upon.

It is the theory that the lines of the fingers of every person in the universe form patterns, which have no exact duplicate, and that moreover, these lines remain unchanged in an individual’s hand from his birth to his death.

It is a rather awesome reflection. Look at your finger – and consider that there is nothing else like them in the whole universe and that probably there never will be. It reminds one of the story of the little boy who after having been told of the wonders of nature looked up at his teacher with a puzzled hair and asked if the Lord didn’t ever run out of ideas. It seemed too big to be true. Still that is the principle upon which the Henry finger – print system is based.

TAKING THE PRINTS

If the skin of the hand be destroyed and grows back again in a natural manner, its lines, after it has completed its growth, will be identical with those of the skin that was destroyed. It really seems as if fate had stamped a trademark upon the hand of each individual. At all events only, thing that will permanently destroy the telltale lines is a scar.

If you have ever gone to a palmist and had him (or her, as the case is more apt to be) smear your hand with black ink and press it on a piece of white paper, you will understand that once just how the fingerprint system is worked. If the palmist as afterward examined this impression with a magnifying glass and discovered interesting things in it you will know also how the print is classified and filed in the Henry system of criminal identification.

The making of fingerprints consists of a clever use of glass and printers bank and a bit of care. The ink is usually black, or if not that, of some intense color, and is the same as that used for printing fine cuts or engravings. The glass is a strip about 5 x 6”. Upon the glass the ink is spread in a thin coating.

Then a paper form with spaces reserved for the impression of the different fingers is laid upon the table beside the ink and the glass and all is in readiness to take the prints of the fingers of the person whose record is desired.

PRISONERS ARE FRIGHTENED

These preparations are all very simple. They certainly don’t seem to have anything in them to frighten a person. But prisoners in the Baltimore Bureau who are to be finger – printed seem always to regard them in a respectfully timid way. They think that there is some sort of a “hoodoo” about them. With the colored gentry this is especially true. The idea of making a finger – print evidently seems possessed of menace to them.

12 prints are made from each individual to be recorded. First each of the 10 fingers is printed separately; then the forefingers of each and together. A simple role of the ink on the glass and a pressure upon the paper constitutes the whole mechanical part of the operation.

The next step in the making of the fingerprint record is a classification and filing.

The first term may not be understood, but the second seems simple enough. “Filing;” the word instantly brings to mind a picture of cabinets with their content arranged alphabetically.

Filing a finger – print with us seem to be very easy of comprehension. In reality, it is the most difficult part of the process. Finger – Prince cannot be filed according to the alphabet. They must be put away according to fixed characteristics of their own, and this is why they must be classified before they can be filed.

Suppose a man is in custody. It is thought that he has a finger – print record, and that this record is desired by police officials. Would it be possible to look for it under the name the man gives? Certainly not, because this is, just as well as not, and alley us.

That is the whole point. If names were fixed quality in life and could not be changed they would serve as a means of identification. Otherwise identity must be ascertained by means of an individual’s personal characteristics. In this case a finger – print record must be found by means of a finger – print and not by name.

SORTING THE PRINTS

The task of devising a means by which finger – prints could be filed was one of the greatest difficulty. By successfully carrying it through Mr. Henry gave his name to the process now standing as a monument to him. The peculiar virtues of finger – prints as a means of identification were known before his time, but there was no way to classify them.

Through the study of several thousand finger – prints which he had collected while in service in India, where the government has long had them used for signatures among the lower castes of natives, Mr. Henry came to the conclusion that there were two great classes into which all fingerprints could be divided. In other words, he found that there were certain general designs upon which the patterns of all finger ends were based. These designs he named “arches,” “loops” and “whorls” and “composites.” Arches or loops occur wherever no single line of the fingertip makes a complete circle. Whorls are formed wherever a line does a complete circle. Composites are a sort of hybrid pattern partaking more of the nature of the whorl than of a loop. The proportions of these three classes he found to be as follows:

Arches, 5%.

Loops, 60%.

Whorls and composites, 35%

Since the number of arches was found to be inconsiderable, Mr. Henry place them in a single class with the loops. Whorls and composites were very easily associable. Thus Mr. Henry had two great natural classes and was all fingerprints could be divided

THE 1,024 CLASSES

In every finger record there are 10 separate prints to be considered. Either one of these prints can be one of two classes, and there are a number of combinations that might be formed among fingers of different classes. For instance, there might be five loops and five whorls, where there might be for loops and six whorls, and so one. The point was to find out how many classes there might be. This Mr. Henry set himself to do. If he discovered exactly the number of classes in a primary classification of his finger – prints he would be able to commence a system of filing.

One of the simplest propositions and higher mathematics is the find out the number of possible combinations among a given number of objects. A very simple formula has been worked out for this purpose. By this formula Mr. Henry ascertained that was sets of two and 10 objects there was a possibility of 1,024 combinations.

Accordingly, if a cabinet should be instructed to hold 1024 drawers, the bases of a reliable system of filing finger – prints was at hand. Now 1024 is a square of 32, so the cabinet might very conveniently be made with 32 drawers each way.

It is useless to follow the process of finger – record filing further. It simply becomes more complicated as one goes on. It is sufficient to say that the 1024 primary classes can be subdivided by minor peculiarities of finger – prints, which Mr. Henry enumerates in his book dealing with the subject, and so the process is elastic and will accommodate any number of records. In an up-to-date print Bureau, a record can be found or filed in less than two minutes time.

ORIGINATED IN INDIA

The finger – print system originated in India and came from that country by way of British conquest and the St. Louis exposition to Baltimore and America. In all the Eastern countries the value of finger – prints has been known from time immemorial. In China, indeed, there is a pleasing little story about an ancient Empress whose official seal for all the coinage of her realm was her finger and Prussian. At any rate, for many centuries before the British took possession of India finger – prints had been used as signatures among the lower castes.

After the Empire had been established governmental difficulties with natives who impersonate each other for the sake of fraudulently receiving pensions became so great that some method had to be found by which one Indian could be told from another. The finger – print method, which had been observed among the natives themselves, was adopted as a happy solution and proved itself all that could be desired.

At first finger – prints were used only in the government departments in India in lieu of signatures. Then they were taken up by the police department also. Notably this was the case in the Bengal Bureau. Mr. E. R. Henry was then a young subaltern in the branch.

Years afterward, when Mr. Henry was appointed chief of Scotland Yard, in London, he took his Indian method with them. When he saw the immense need of a systemized use of finger – prints he perfected his method of classification and filing alluded to above and gave his invention to the world.

SCOTLAND YARD THE FIRST

Scotland Yard was – of course – the first police Bureau among civilized nations to receive the benefit of the Henry method. His introduction there took place in 1897, and it was made an adjunct to the Bertillon method. Its complete adequacy for attending to the duties of identification by itself, however, soon convinced the English officials of the superfluity of the older method, so the time tried Bertillon system was dropped.

When the St. Louis exposition was opened here in 1904 the British government sent a delegation from Scotland Yard to demonstrate the effectiveness of its new system. The national Association of Chiefs of police was in session in St. Louis at that time, and the English representative took advantage of the opportunity to address them upon the new method of identification. This is the combination of circumstances that brought the system to the United States.

Marshal Farnan of the Baltimore Police Department was one of those who heard the lecture upon the finger – print method. He was much impressed and sought an opportunity to speak personally with the lecture. When he returned to Baltimore at the conclusion of the convention he sought out Sgt. Casey, of the Bureau of identification, confided to him his knowledge and delegated him to visit St. Louis and receives special lessons in this new system.

Sgt. Casey departed an incredulous scoffer and returned an enthusiastic convert. His zeal in the work has made the Baltimore Bureau one of the most favorably known in the country. The department was established here 17 December 1904, and was followed shortly by others in other big cities of the United States.

EXIT, M. BERTILLON

It has been often asked of late in police circles if the finger – print method whatever holy supersede the Bertillon method in the United States. In case the example of Europe be followed, it most certainly will. There is now no great nation in the old country, with a single exception of France, where the Bertillon method was born, that does not use the finger – print system exclusively.

The advantages of the finger – print method are that it is cheaper, simpler and more reliable. The personal element of the operators of efficiency or non-efficiency does not materially alter the results. Finally, the instruments of its use are neither many nor costly. In this last point especially, the Bertillon method lags far behind. Special and delicate instruments of much cost have been installed before it can be successfully practiced.

An application of finger – prints that has caused much interest is in the detection of criminals. Suppose a burglar enters the house and leaves his finger – Mark a pond the windowpane. No other clue was wanted by the enterprising police of today. The pain is carefully taken out and sent to the Bureau of identification. There the prints are classified.

Then someone looks into the file, turned over a few leaves and, presto! If the burglar is an old offender, his name, photograph, criminal record and habits of living are staring one in the face. It sounds like a fairytale, but the experiment really has been tried with complete success in England.

WHERE SCIENCE FAILED

In Baltimore not long since it was thought that this same idea could be given an application in connection with the Cunningham Negro murder case. The search was for the murder. In the victim’s room were found the number of checks with black finger marks upon them. The police generally were jubilant, and Sgt. Casey exalted. Here at last, it was thought, was a chance to throw the limelight on the fingerprint Bureau. Finally, it transpired that the marks were not those of the murder, but of an enthusiastic member of the detective corps who, in raking around among the ashes of the hearth for clues, had gotten his fingers dirty and had then picked up the bunch of checks. Science had a downfall.

Whenever scientific knowledge develops unique features it is immediately applied in a popular form for the past time of the people. In this case finger – prints have received an ingenious embodiment by a novelty house, which is sold a little book containing a pad of ink and a number of blank pages. “Flugeraphs” are to take the place of autographs. Soon, instead of the fiend who want your name and favored bit of poetry, one will be pursued by the hobbyists in finger – prints. Smutty fingers and black males will be all the rage. Since some say, at all events. It remains to be seen.

Sir Edward Richard Henry, 1st Baronet

(26 July 1850 – 19 February 1931)

Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis

(Head of the Metropolitan Police of London)

1903 to 1918.

Sir Henry was Best Known for

The introduction of K9 Dogs for use with Police, and Fingerprinting for the purposes of identifying criminals.

Early Life – Sir Henry was born at Shadwell, London to Irish parents; his father was a doctor. He studied at St Edmund's College, Ware, Hertfordshire, and at sixteen he joined Lloyd's of London as a clerk.

He meanwhile took evening classes at University College, London to prepare for the entrance examination of the Indian Civil Service.

Early service in India

On 9 July 1873, he passed the Indian Civil Service Examinations and was 'appointed by the (Her Majesty's) said [Principal] Secretary of State (Secretary of State for India) to be a member of the Civil Service at the Presidency of Fort William in Bengal'.

On 28 July 1873 he married Mary Lister at St. Mary Abbots, the Parish Church of Kensington, London. Mary's father, Tom Lister was the Estate Manager for the Earl of Stamford.

In September 1873 Edward Henry set sail for India. He arrived in Bombay and travelled across India arriving at Allahabad on 22 October 1873 to take up the position of Assistant Magistrate Collector within the Bengal Taxation Service.

He became fluent in Urdu and Hindi. In 1888, he was promoted to Magistrate-Collector. In 1890, he became aide-de-camp and secretary to the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal and Joint Secretary to the Board of Revenue of Bengal.

On 24 November 1890, as a widower, he remarried, by marrying Louisa Langrishe Moore.

Inspector-General of Police

On 2 April 1891, Henry was appointed Inspector-General of Police of Bengal. He had already been exchanging letters with Francis Galton regarding the use of fingerprinting to identify criminals, either instead of, or in addition to the anthropometric method of Alphonse Bertillon, which Henry introduced into the Bengal police department.

The taking of fingerprints and palm prints had been common among officialdom in Bengal as a means of identification for 40 years, having been introduced by Sir William Herschel, but it was not used by the police and there was no system of simple sorting to allow rapid identification of an individual print (although classification of types was already used).

Between July 1896 and February 1897, with the assistance of Sub-Inspectors Azizul Haque and Hemchandra Bose, Henry developed a system of fingerprint classification enabling fingerprint records to be organized and searched with relative ease. It was Haque who was primarily responsible for developing a mathematical formula to supplement Henry's idea of sorting in 1,024 pigeon holes based on fingerprint patterns. Years later, both Haque and Bose, on Henry's recommendation, received recognition by the British Government for their contribution to the development of fingerprint classification.

In 1897, the Government of India published Henry's monograph, Classification and Uses of Fingerprints. The Henry Classification System quickly caught on with other police forces, and in July 1897 Victor Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin, the Governor-General of India, decreed that fingerprinting should be made an official policy of the British Raj. This classification system was developed to facilitate orderly storage and faster search of fingerprint cards, called ten print cards. It was used when the ten print cards were cataloged and searched manually and not digitally. Each ten-print card was tagged with attributes that can vary from 1/1 to 32/32.

In 1899, the use of fingerprint experts in court was recognized by the Indian Evidence Act.

In 1898, he was made a Companion of the Star of India (CSI).

In 1900, Henry was seconded to South Africa to organize the civil police in Pretoria and Johannesburg.

In the same year, while on leave in London, Henry spoke before the Home Office Belper Committee on the identification of criminals on the merits of Bertillonage and fingerprinting.

Assistant Commissioner (Crime)

In 1901, Henry was recalled to Britain to take up the office of Assistant Commissioner (Crime) at Scotland Yard, in charge of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID).

On 1 July 1901, Henry established the Metropolitan Police Fingerprint Bureau, Britain's first. Its primary purpose was originally not to assist in identifying criminals, but to prevent criminals from concealing previous convictions from the police, courts and prisons.

However, it was used to ensure the conviction of burglar Harry Jackson in 1902 and soon caught on with CID. This usage was later cemented when fingerprint evidence was used to secure the convictions of Alfred and Albert Stratton for murder in 1905.

Henry introduced other innovations as well. He bought the first typewriters to be used in Scotland Yard outside the Registry, replacing the laborious hand copying of the clerks.

In 1902, he ran a private telegraph line from Paddington Green Police Station to his home, and later replaced it with a telephone in 1904.

Commissioner

On Sir Edward Bradford's retirement in 1903, Henry was appointed Commissioner, which had always been the Home Office's plan.

Henry is generally regarded as one of the great Commissioners. He was responsible for dragging the Metropolitan Police into the modern day, and away from the class-ridden Victorian era. However, as Commissioner, he began to lose touch with his men, as others before him had done.

He continued with his technological innovations, installing telephones in all divisional stations and standardizing the use of police boxes, which Bradford had introduced as an experiment but never expanded upon.

He also soon increased the strength of the force by 1,600 men and introduced the first proper training for new constables.

In 1905, Henry was made a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (CVO) and the following year was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (KCVO). In 1910 he was made Knight Commander of the Bath (KCB). In 1911, he was created a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (GCVO) after attending the King and Queen at the Delhi Durbar.

He was also a Grand Cross of the Dannebrog of Denmark, a Commander of the Légion d'honneur of France, and a member of the Order of Vila Viçosa of Portugal and the Order of St. Sava of Yugoslavia, as well as an Extra Equerry to the King.

Henry was awarded the King's Police Medal (KPM) in the 1909 Birthday Honours.

Attempted assassination

On Wednesday 27 November 1912, while at his home in Kensington, Henry survived an assassination attempt by one Alfred Bowes (also reported as "Albert" Bowes), a disgruntled cab driver whose license application had been refused.

Bowes fired three shots with a revolver when Sir Edward opened his front door: two missed, and the third pierced Sir Edward's abdomen, missing all the vital organs. Sir Edward's chauffeur then tackled his assailant. Bowes faced a life sentence for attempted murder

Sir Edward appeared at court and followed a humane tradition of pleading for leniency for his attacker, stating that Bowes had wanted to better himself and earn a living to improve the lot of his widowed mother. Bowes was sentenced to 15 years' penal servitude, but Sir Edward maintained an interest in his fate, and eventually paid for his passage to Canada for a fresh start when Bowes was released from prison in 1922

Sir Edward never really recovered from the ordeal, and the pain of the bullet wound recurred for the rest of his life.

First World War

Henry would have retired in 1914, but the outbreak of the First World War convinced him to remain in office, as his designated successor, General Sir Nevil Macready, was required by the War Office, where he was Adjutant-General. He remained in office throughout the war.

The end of Henry's career came about due to the police strike of 1918. Police pay had not kept up with wartime inflation, and their conditions of service and pension arrangements were also poor.

On 30 August 1918, 11,000 officers of the Metropolitan Police and City of London Police went on strike while Henry was on leave. The frightened government gave in to almost all their demands. Feeling let down both by his men and by the government, whom he saw as encouraging trade unionism within the police (something he vehemently disagreed with), Henry immediately resigned on 31 August. He was widely seen as a scapegoat for political failures.

Later life

On 25 November 1918, Henry was created a baronet, and in 1920 he and his family retired to Cissbury, near Ascot, Berkshire.

He continued to be involved in fingerprinting advances and was on the committee of the Athenaeum Club and the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, as well as serving as a Justice of the Peace for Berkshire. He died at his home in 1931 of a heart attack, aged 80.

The Baronetcy became extinct, since his only son (he also had two daughters), Edward John Grey Henry, had died in 1930 at the age of 22.

His grave lay unattended for many years. In April 1992, it was located in the cemetery adjoining All Souls Church, South Ascot by Metropolitan Police Fingerprint Expert Maurice Garvie & his wife Janis. After a presentation by Maurice Garvie to The Fingerprint Society on the Life & Times of Sir Edward, the Fingerprint Society agreed to the funding and restoration of the grave which was completed in 1994.

In the Metropolitan Police Fingerprint Bureau Centenary Year, 2001, at the suggestion of Maurice Garvie, English Heritage in honor of Sir Edward Henry unveiled a Blue Plaque on his former London home, 19 Sheffield Terrace, Kensington, W.8. The year before, following an approach by Maurice Garvie, Berkshire County Council unveiled on Sir Edward's retirement home 'Cissbury' a Berkshire County Council Heritage Green Plaque.

Baltimore City Police History – Baltimore Police Department becomes the First agency in the United States to use the Fingerprint Identification system to catalog criminals I have seen other sites (written in modern times) use years as dates, but none of them name, names, here we have newspaper articles that were written in 1904, 1905, and 1907… that not only provide dates, but gives the names of who did the finger-printing, who was finger-printed, and for what. So, we know on 26 November, 1904, Sgt. Casey finger-printed John Randles on a theft charge. We also know from those articles that Baltimore’s finger-print system of identification “The finger-print system of identification was inaugurated [Wednesday] 7 December last [1904]” in the Baltimore Police Department’s Bureau of Identification.” From other articles giving estimated dates say, “Sometime” when they said, “sometime after the St. Louis World's Fair, the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) created America's first national fingerprint repository, called the National Bureau of Criminal Identification.” Baltimore had already established an Identification section from one of the other sites, http://onin.com/fp/fphistory.html 1904

The use of fingerprints began in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in Kansas, and the St. Louis Police Department. They were assisted by a Sergeant from Scotland Yard who had been on duty at the St. Louis World's Fair Exposition guarding the British Display. “Sometime” after the St. Louis World's Fair, the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) created America's first national fingerprint repository, called the National Bureau of Criminal Identification.

SEE DEPUTY MARSHAL SAMUEL W HOUSE

Donations

Donations help with web hosting, stamps and materials and the cost of keeping the website online. Thank you so much for helping BCPH.

POLICE INFORMATION

Copies of: Your Baltimore Police Department Class Photo, Pictures of our Officers, Vehicles, Equipment, Newspaper Articles relating to our department and or officers, Old Departmental Newsletters, Lookouts, Wanted Posters, and or Brochures. Information on Deceased Officers and anything that may help Preserve the History and Proud Traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to Honor the fine men and women who have served with Honor and Distinction at the Baltimore Police Department.

Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. follow us on Twitter @BaltoPoliceHist or like us on Facebook or mail pics to 8138 Dundalk Ave. Baltimore Md. 21222

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll