New Department March 1862

There are many things in history that no one today can change, but that have over the years seen changes and many improvements for the better. It is true that at one time Baltimore police officers, or Patrolman to be more precise were given orders to chase and arrest slaves, this was long before today’s Baltimore Police Department, and in fact today’s Baltimore Police Department is not the same Baltimore Police Department in more ways than the obvious. If we were to shut down todays department and start a new department tomorrow in this city for obvious reasons it would be called Baltimore City Police Department. Truth of the matter is, todays Baltimore City Police Department has never made an arrest for slaves, the Baltimore Police Department that made slave arrests ended on 27 June, 1861 when new police commissioners were appointed by the U.S. Military authorities under direction of then president Abraham Lincoln as the former BOC (Board Of Commissioners) was replaced with Columbus O'Donnell, Archibald Sterling Jr., Thomas Kelso, John R Kelso, John W Randolph, Peter Sauerwein, John B Seidenstricker, Joseph Roberts, and Michael Warner. All police prior to 27 June 1861 were dismissed from the police force and had to reapply with only the best of the former police being rehired and many left for good. One might also be interested in knowing at the time Baltimore was not as big as it is today, and the city had less than 300 police officers closer to 220 maybe 250. During the next year between June of 1861 and March 1862, the streets were protected by military police. On 3 April 1862 our newly sworn police officers stepped in, wearing a new uniform, a new badge with a new police authority, new rules, under new laws, and new leadership, While Slavery in this country was not abolished until 1864, slave arrest in Baltimore were no longer being made by our police officers. The time between 27 June 1861 and 3 April 1862 the replacement temporary fill in law enforcement wore plain clothes, and were only recognized by a simple, "Pink Ribbon" worn on their left lapel, along with an, "Espantoon" carried for the safety of the public and, the officer's protection. Other than those two identifiers, a uniform for the newly built Baltimore Police Department had not yet been selected, and so until it was, they dressed in civilian attire.

Note: Many of these provost officers were hired on fulltime as the new Baltimore Police, to take the place of the abolished officers.

The reason for the change was largely due to not just Marshal Kane, and the BOC at the time, but also because of Mayor Brown and City Hall. Many believe after the 18 April 1861 riots on Howard Street where Baltimore civilians attacked U.S. Military on its way to Washington DC in preparation of the war between the states, Mayor Brown and Marshal Kane may have hatched a plan for a second attack to take place a day later, on 19 April 1861 at Pratt and President Streets. There are said to have been telegraphs sent from Kane to his confederate army allies telling them where and when to begin their attack on the 6th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, a volunteer militia, who passed from the President Street Station a little over 1 mile west, at Camden Station (now Camden Yards). The 6th Massachusetts Infantry were in route to Washington D.C. as were the troops just one day earlier when attacked on Howard Street. It is awfully odd that a day after that Howard Street attacks, Marshal Kane would have some of his men across town, and others stationed at the end of the soldiers’ route and not at the beginning where they knew the soldiers would be departing the trains coming in from the north before transferring to another set of trains to take them into Washington DC. But the fact is, Marshal George Proctor Kane was arrested, he was found to have been funneling police ammo, weapons, and equipment to the Confederate Army. Kane was first taken to Fort McHenry, but at the request of the fort’s commander, Kane was moved to Ft Warren, Massachusetts. His position as Marshal of Police, and his southern sympathies were well known, and a large part as to why the department with several likeminded officers was disbanded during that June of 1861 and rebuilt into a new department, that started having meeting and firming in March of the following year but didn’t actually hit the streets until the 3rd of April 1862. There we have it, it was officially on that 3rd day of April 1862 when Baltimore City’s new Police Department with its new uniforms, new men, under new leadership hit the streets, and as that new agency it has never made slavery arrests. Note: until 1864 there were still Slave agents working in a private sector for slave owners, they would seeks warrants, and collect bounties for so called runaway slaves, when arrested by those bounty hunters they would bring them local jails, one such incident occurred on 31 May, 1862, when Isaac Brown, was picked up by bounty hunters and charged with being a runaway slave charges fled with the courts by Hamilton Stump who lived at the corner of Paca & Lombard Street. Mr. Brown was held in one of our lockups pending a hearing. It should also be known that in the nearly 160 years since that 27th day of June 1861, other than those picked up by bounty hunters on warrants in which case our turnkeys would have been ordered by the courts by court documents, to take them in. From what we can find in documents, and newspaper reports the new Baltimore Police Department's themselves didn't actively seek, or search for, and arrest slaves. Just as with any family, there have been changes, many changes, many times over until it is nowhere near the agency it was even 20 years ago, much less the agency it was more than 150 years ago since it was newly formed in 1862 or nearly 300 years ago in 1729 when the city first began it's quest for the preservation of the peace, protection of property and to arrest offenders became a goal of Baltimore residents on 8 August, 1729 when the Legislature created Baltimore Town. This town went through some ugly times trying to form a better police force as is also evident of this article - 172 Years of Policing in Baltimore HERE and Baltimore's Roistering Past HERE unlike today where have between 2500 and 3000 police in Baltimore, in 1862 we had a much smaller city and just 232 police for the entire city. Like today the larger part of the majority of our police are activist for the victims of crime, but at the same time we have compassion for the criminals we are forced to arrest by their own actions.

We hope this page helps our visitors to learn more about our police past and present, if you have questions, or further information feel free to send to us via the following email address: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

On 13 May, 1861, the Union army entered Baltimore, occupied the city, and declared martial law. Mayor Brown was arrested on 12 September, 1861 at his home. He was imprisoned at Fort McHenry for one night. He was transported to Fort Monroe in Hampton Roads, Virginia, and held for two weeks. Next, he was moved to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor and held for fourteen months. He was released on 27 November, 1862. He returned to Baltimore and resumed his law practice. Francis Key Howard, the grandson of Francis Scott Key was also made a prisoner.

History tells of Mayor George William Brown playing an important role in controlling the Pratt Street Riot, where on 19 April, 1861 the first loss of life through bloodshed of the Civil War occurred. During the riot, Brown was said to have accompanied a column of the 6th Massachusetts regiment through the streets. When the column he was leading was assailed by the mob, "the mayor's patience was soon exhausted, and he seized a musket from the hands of one of the men and killed a man therewith." Immediately following the Riot, Baltimore saw much lawlessness, as citizens destroyed the offices of pro-Union German newspapers and looted shops in search of guns and other weapons. Mayor Brown and Maryland businessmen were said to have visited the White House to urge President Abraham Lincoln to reroute Union troops around Baltimore city to Annapolis to avoid further confrontations that they felt would result from additional troops passing through the city.

Others believe, and history would suggest, Brown wasn't trying to bring aid to Massachusetts' 6th regiment, moreover that he and Marshal Kane hatched the plan that helped lead to the deaths of four of those soldiers and serious injuries to 35 more, as well as the costing the lives of eleven Baltimore citizens during riots that could have, and should have been prevented. If we would consider the events that took place just one day earlier on Howard Street as the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry, and Washington Artillery militia companies of US Artillery, and militia arrived from Harrisburg to Baltimore's Bolton Station. A large crowd assembled at the station, subjecting the militia to verbal abuse and threats. According to the mayor at the time, “An attack would certainly have been made but for the vigilance and determination of Baltimore's police, under the command of Marshal Kane.” However, records show it was a little more than peaceful protests, with some harsh name calling as several members of those troops received serous injuries, from the rocks, bottles and bricks that were hurled into the troops as they marched down Howard Street. There were injuries, however there was no life loss on that day. In John David Hoptak's book, Dear Ma - Curtis Clay Pollock wrote home in letters to his mother of the events of 18 April 1861 - On 17 April of that fateful year, just five days after the war's opening at Ft Sumter and in response to President Abraham Lincoln’s call to arms, an 18-year-old boy by the name of Curtis Pollock marched off to war. He was made a Private in the Washington Artillery, a militia company recruited from the young volunteer’s hometown of Pottsville, Pennsylvania. Curtis Clay Pollock was one of among the more than two million soldiers who donned a Union blue and fought in defense of the United States during the American Civil War. And, by war’s end, he would be counted among the many hundreds of thousands of those soldiers who died to help ensure that this nation might live. He was among the very first to respond to his countries call, volunteering his service immediately upon the outbreak of hostilities in the spring of 1861. The very next evening, the Washington Artillery, along with four other companies of Pennsylvania volunteers, arrived in the distressed Nation’s Capital. As it turned out, these men, Pollock included, would be the very first Northern Volunteers to arrive in Washington following the commencement of the war and would go down in history as part of the famed "First Defenders." As earlier that same day (18 April 1861) as the volunteer soldiers of these companies they made their way through the streets of Baltimore on their journey south to Washington, they were assaulted by a vehement mob of Pro-Confederate sympathizers who hurled not only insults, but also bricks, bottles, and stones. Pollock wrote home to his mother. Pollock escaped injury, but some of the Pennsylvanians were not so lucky as they had become part of the troops that were struck down and seriously injured during the melee, thereby shedding some of the very first blood in what would prove to be America’s bloodiest war. This book serves as more written documentation of the first day of fighting in Baltimore's two days of rioting in our streets. The first day, 18 April 1861 led to the first bloodshed of the civil war, the next day on the 19th the country would have it's first deaths of the War Between the States.

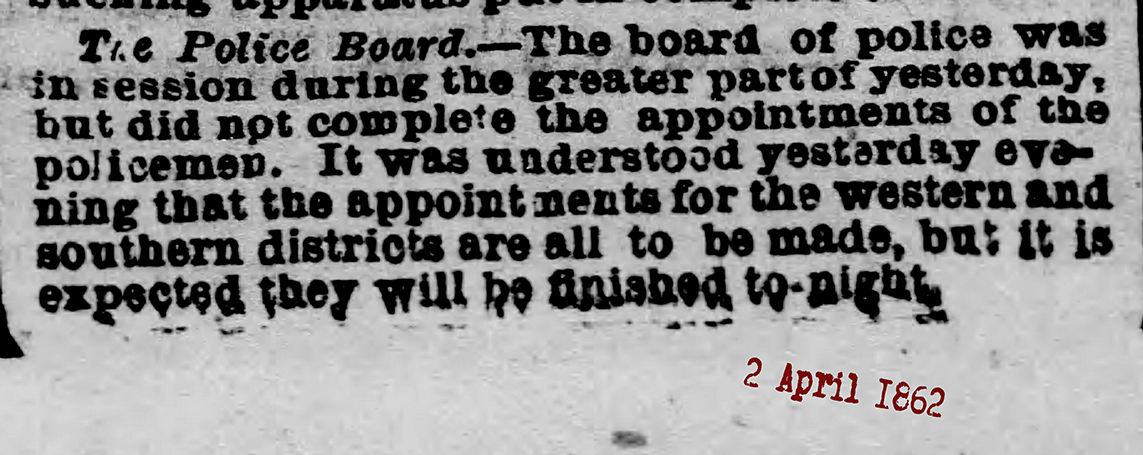

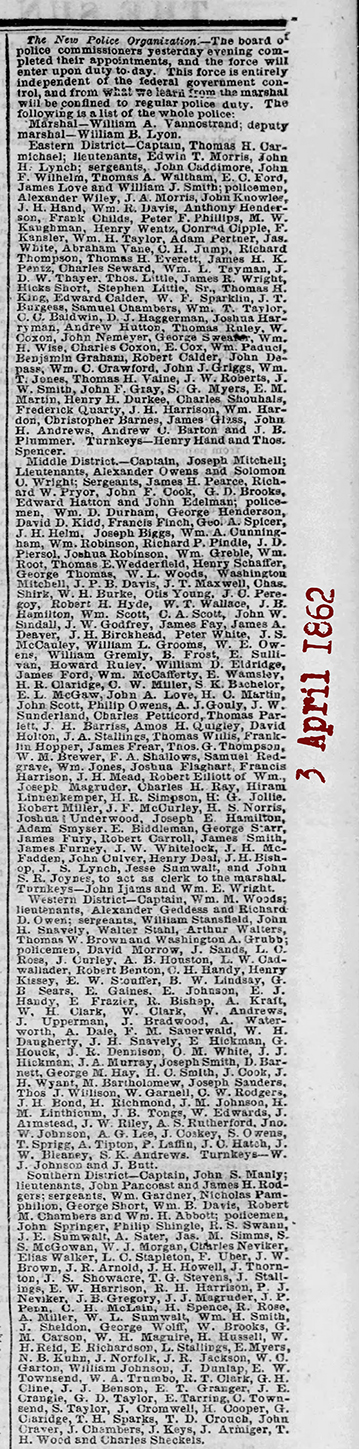

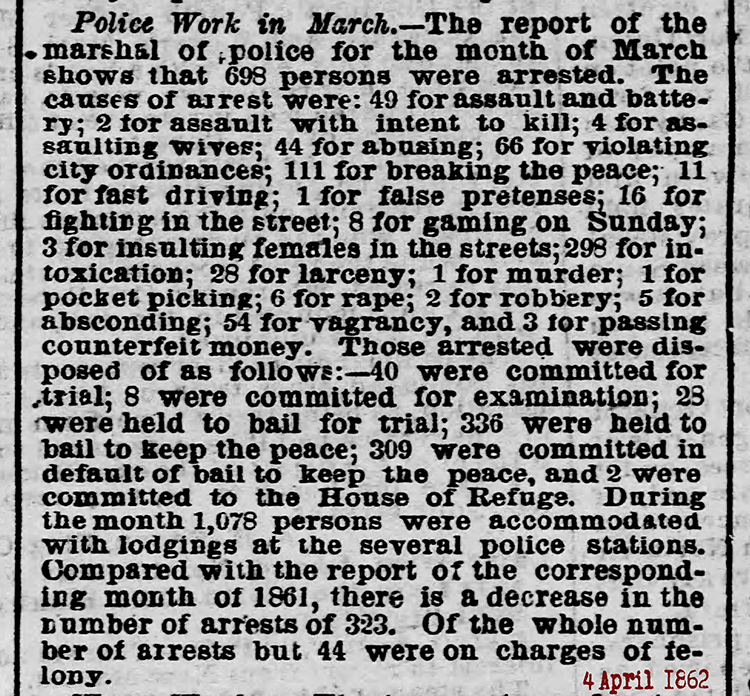

The following are articles written in 1862 referencing those early changes as they occurred.

Sun Paper Article 2 April 1862

Click HERE for full article

Sun Paper Article 3 April 1862

Click HERE for full article

Sun Paper Article 4 April 1862

Sun Paper Article 4 April 1862

Click HERE for full article

Sun Paper Article 4 April 1862

Sun Paper Article 4 April 1862

Click HERE for full article

Sun Paper Article 22 March 1862

Sun Paper Article 22 March 1862

Click HERE for full article

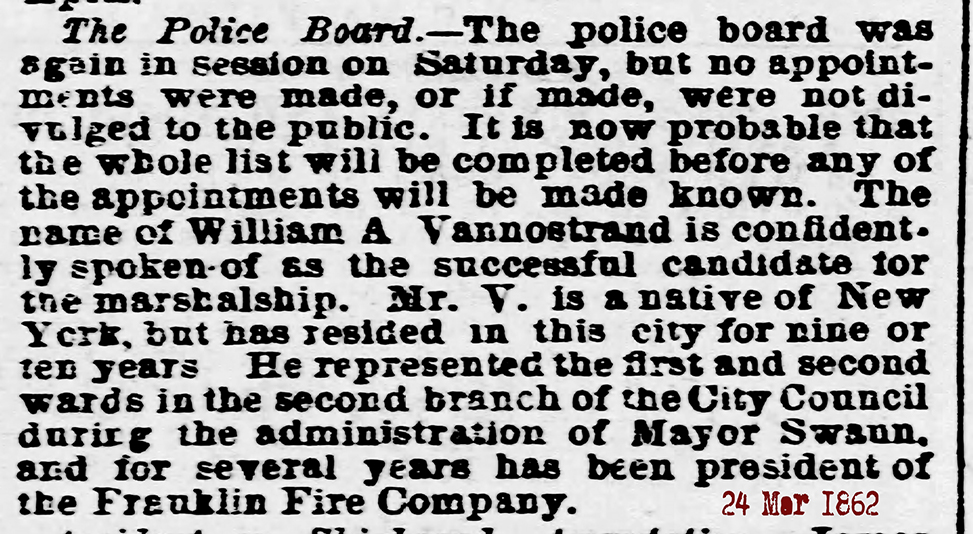

Sun Paper Article 24 March 1862

Sun Paper Article 24 March 1862

Click HERE for full article

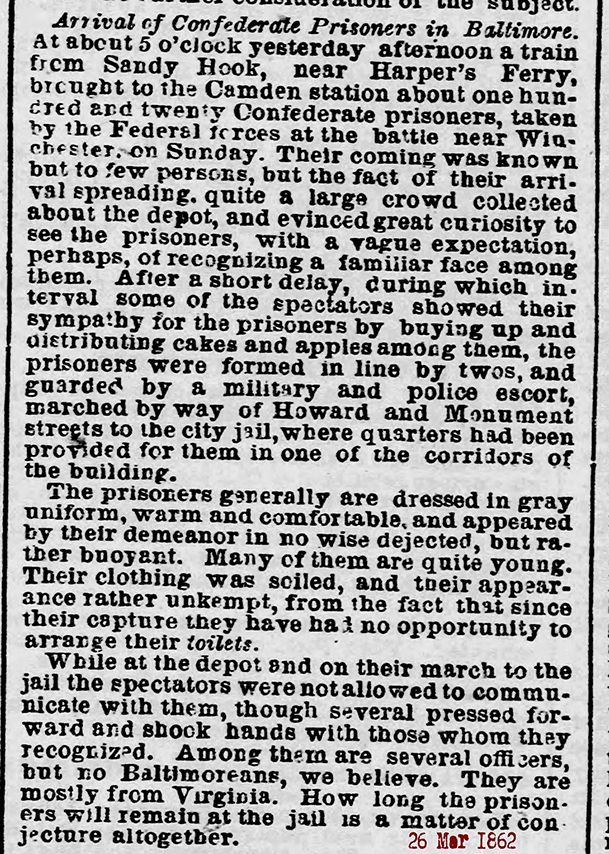

Sun Paper Article 26 March 1862

Sun Paper Article 26 March 1862

Click HERE for full article

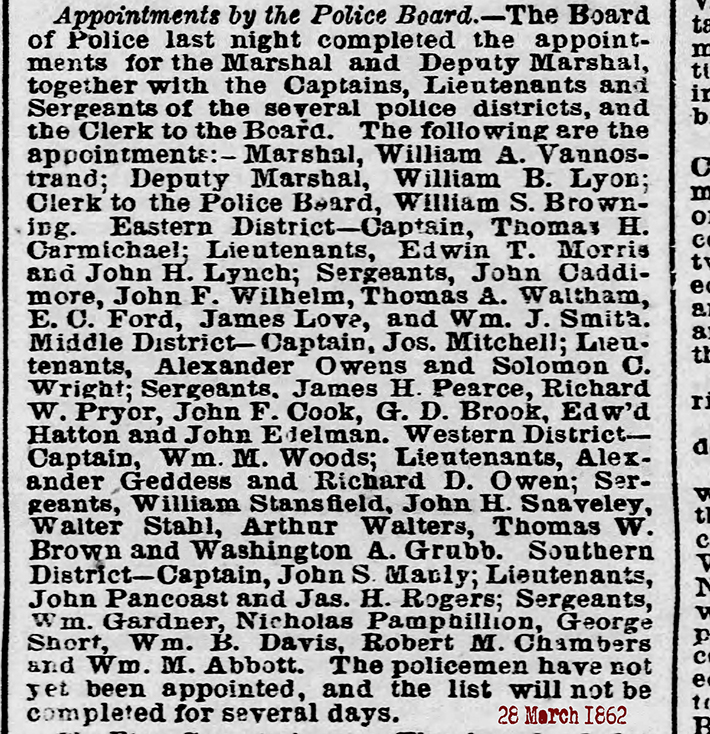

Sun Paper Article 28 March 1862

Sun Paper Article 28 March 1862

Click HERE for full article

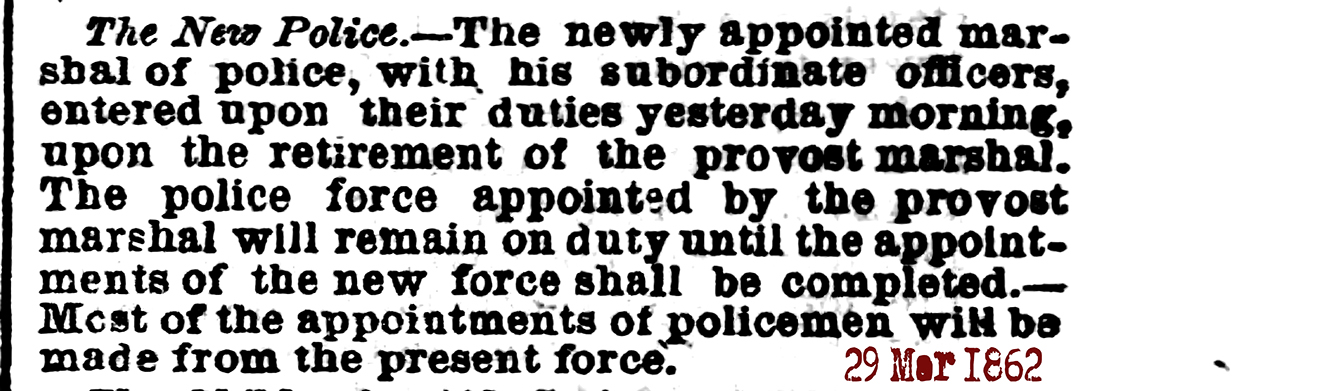

Sun Paper Article 29 March 1862

Sun Paper Article 29 March 1862

Click HERE for full article

Sun Paper Article 31 March 1862

Sun Paper Article 31 March 1862

Click HERE for full article

Sun Paper Article 31 March 1862

Sun Paper Article 31 March 1862

Click HERE for full article

POLICE INFORMATION

Copies of: Your Baltimore Police Department Class Photo, Pictures of our Officers, Vehicles, Equipment, Newspaper Articles relating to our department and or officers, Old Departmental Newsletters, Lookouts, Wanted Posters, and or Brochures. Information on Deceased Officers and anything that may help Preserve the History and Proud Traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to Honor the fine men and women who have served with Honor and Distinction at the Baltimore Police Department.

Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. follow us on Twitter @BaltoPoliceHist or like us on Facebook or mail pics to 8138 Dundalk Ave. Baltimore Md. 21222

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll