Sgt Jack L Cooper

Sgt Jack L Cooper

CLICK HERE FOR AUDIO

On this date, December 25, 1964, we lost our brother, Sgt Jack L Cooper, to gun fire based on the following:

Baltimore Sun Article Dated 12/26/1964

A police Sergeant was shot to death early yesterday as he was searching for a bandit who had wounded a police lieutenant in a Christmas Eve liquor store hold up. Sgt. Jack L. Cooper, 43, was shot twice through the heart shortly before 5 a.m. as he was working by himself in the 2600 Block of Kennedy Avenue. Lt. Joseph T. Maskell, 40, was shot twice but was not fatally wounded as he struggled with the bandit shortly before 10 p.m. Christmas Eve outside a liquor store in the 2000 Block of Greenmount Avenue. He was in fair condition at St. Joseph’s Hospital. Police said Sergeant Cooper apparently had stopped a 25-year-old man identified by witnesses as one of four men who robbed the liquor store proprietor and several of his customers of $2,399.80. Police found a black leather card case containing the name of the 25-year-old man lying near Sergeant Cooper’s body. They also found a driver’s license issued to the same man lying on the floor of his police car near the clutch pedal. Sergeant Cooper’s pistol was still in its holster when he was found sprawled on the sidewalk, about 10 feet from the open door of his car. At about 4:45 a.m., Sergeant Cooper, Patrolman Charles Kopfelder, and Daniel Sobolewski met in the 1600 block of Carswell Street, about eight blocks northeast from the holdup scene. The two patrolmen left in their police cars to cruise along Gorsuch Avenue. They last saw the sergeant sitting alone in his car. Just before 4:50 a.m., they heard shots and hurried back to the 1600 block of Carswell Street. They found Sergeant Cooper lying on the sidewalk in the 2600 block of Kennedy Avenue. He was bleeding from three bullet wounds. The light in his police car was turned on. Both Sergeant Cooper and Lieutenant Makell worked out of the Northeastern District. Sgt. Cooper served in the U.S. Coast Guard from June 3, 1941, to November 1945. He served in the North Atlantic convoy routes and was discharged as Radio Man, First Class. One retired Sgt. wrote on the Christmas killing of our brother Sgt. Cooper that someone else was correct in their beliefs that Sgt. Cooper was shot and killed by one of the Veney Brothers (Sam and Earl). "Yes, it was the Veney brothers. I was a patrolman at the time in the Northern District, working for Joe Maskell when he was a Sergeant in the Northern. I gave a pint of blood at St. Joe's. The liquor store was Lexie's and was always being held up. After the shooting and during the months of searching for the Veney brothers, we must have raided every house in the area at one time or another. It was the first and last time I ever carried a Thompson 45-cal machine gun. The truck would pull up to a corner, and we would all line up, be issued shotguns or Thompson's, and be told what we were going to hit. We would raid a whole block, kick in all the doors, and start searching. I was with George Shriner one time and remember his placing his Thompson near a sleeping man's mouth, and when the guy woke up, he raised his head, and it was as if he could have rammed the gun into his throat. I still can't figure out how someone wasn't killed during that time. The thing about it was that it was a different time; there were so many tips coming in, and none of us knew what was being said or by whom. All we knew was that they shot two of ours, killing one, and none of us wanted to be next. One of the Veney's was arrested in New York State and lived disguised as a woman. The ACLU took the Baltimore Police Department to the Supreme Court, protesting the tactics used to find these jerks. The results changed the probable cause for searching for suspects in the future. No more anonymous tip searches. Years later, after I retired, I was the Director of Security at Lexington Market, and I happened to hear that one of the Veney's was cashing pay checks at the market. . Someone dropped a dime on the right person, and a big stink was made. His work release suddenly stopped.

From this, I learned what to look for and found the following: The Veney Brothers were Sam and Earl Veney, Sam actually pulled the trigger on that night, ruining a lot of lives. The following information might be of some interest; it was found in Baltimore Sun archives

Joseph T. Maskell, 73, Officer Shot in the Notorious 1964 Case

April 17, 1998 | By Fred Rasmussen | Fred Rasmussen,SUN STAFF

Joseph T. Maskell, a retired Baltimore police lieutenant who was shot in a 1964 robbery that began the notorious Veney brothers case, died of lung cancer April 10, 1998, at his Mount Washington home. He was 73. Lieutenant Maskell joined the Police Department in 1946 and, after recovering from his wounds, retired in 1966. He became an adjuster for an insurance company and was appointed vice president of marketing at Freestate Adjusting Co. in 1979. He retired again in 1986 and was a rental car salesman until 1990 About 10 p.m. on Christmas Eve in 1964, Lieutenant Maskell, assigned to the Northeastern District, responded to a call about a robbery in progress at the Luxies Liquor store in the 2000 block of Greenmount Ave. "He saw something going on and walked right into a robbery. He was shot twice, and then he staggered to Worsley Street, about 25 feet from Greenmount Avenue, where he was later found," said Bill Rochford, a police lieutenant at the time. "It was a miracle he survived," said Mr. Rochford, a boyhood friend who grew up with Lieutenant Maskell in Northeast Baltimore. Samuel J. Veney and Earl Veney became the targets of the city's largest manhunt. The Veneys made the FBI's 10-most-wanted list, the first time two brothers had been on the list. "The search was intense and went on through the night and into Christmas morning, when Sgt. Jack Lee Cooper was killed by Samuel Veney," said Bill Talbott, a retired Evening Sun reporter who covered the case. During the 19-day manhunt, police searched 200 homes in black communities without obtaining search warrants. The illegal searches prompted the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to file a federal lawsuit that resulted in a 1966 injunction against the city police. The Veney brothers, who had fled the state, were captured in March 1965 while working in a zipper factory on Long Island, N.Y. They were tried and convicted in Frederick, where the case was moved because of pretrial publicity. Earl Veney was sentenced to 30 years in prison and, in 1976, was found hanged in the House of Corrections in Jessup, where Samuel Veney is serving a life sentence. Lieutenant Maskell was awarded two official commendations and received 10 letters of commendation. "He was a very decent guy who never really held any animosity about what happened," Mr. Rochford said. "I think the only regret he had was the fact that it ended his career. In later years, he really never talked about it." Retired Sun reporter Robert A. Erlandson said, "He was the prototypical Irish cop with a big smile and was very caring, and most of all, he was well-liked." A 1942 graduate of City College, Lieutenant Maskell served in the Army Coast Artillery from 1942 to 1945 and was discharged as a staff sergeant. He earned a law enforcement certificate from the University of Maryland in 1963. Graveside services were held Monday. He is survived by his wife of 46 years, the former Gloria Bauer; three daughters, Cynthia DiLiello of Jarrettsville, Mindy Sturgis of Joppatowne, and JoAnne Bell of Fallston; and nine grandchildren.

Sam Veney's Death Sentence

Afro-American Newspaper

FREDERICK: Samuel Jefferson Veney, 27, convicted of the Christmas 1964 murder of Police Sgt. Jack Lee Cooper, must die in the gas chamber. So ruled a two-judge Frederick County Circuit Court panel here late Monday. Sam, the second half of the first brother team ever to make the FBI's "Ten Most Wanted" list,stood Impassively as Judge J. Dudley Diggs pronounced the Supreme penalty. Execution or sentence will be delayed pending outcome of an appeal to the Maryland Court of Appeals. Charges of armed robbery and shooting with intent to murder Police Lt. Joseph T. Maskell were filed by Baltimore State's Attorney Charles E. Moylan, who headed the week-long prosecution before a two-woman and ten-man jury, which returned the verdict offirst first-degree murder guilt. While imposing sentence, Judge Diggs said he and associate Judge Robert E. Clapp Jr. decreed the death penalty after "consciously and unconsciously" searching their minds and concluding there was no justification for not imposing capital punishment. Chief defense counsel John R. Hargrove, arguing against the extreme penalty, said Sam should not be made a ''scapegoat" while others involved in the crime are out walking the streets. Mr. Moylan, on the other hand, declaredthat he could not think of any case where the death penalty would be imposed if it were not imposed in the case of the convicted police killer. Mr. Hargrove noted an immediate intention to appeal.

Putting a Price Tag on that which is priceless—life itself

May 12, 1993, by Gregory P. Kane

CONVICTED cop killer Samuel Veney, who was returned to a Maryland prison Monday, walked away the same weekend two Los Angeles police officers were found guilty of violating Rodney King's civil rights. That was a coincidence, but both Sam Veney and Rodney King were involved in cases where police misconduct became at least as notorious as the misdeeds of either man. Before his brutal beating, King had led police and highway patrolmen on a high-speed car chase. He was quite drunk at the time. My guess is that he had broken at least four laws by the time of his arrest—crimes that were all but forgotten in the furor that resulted from the video of those 82 seconds it took police to subdue him. The case of Sam Veney and his brother Earl is different because their crime was more heinous. They gunned down two Baltimore Police officers, killing one and wounding another, while robbing a liquor store on Greenmount Avenue. The Veney brothers were probably the most notorious and feared criminals in Baltimore history, but police misconduct figured prominently in their crime, too. After the shootings, the Baltimore Police Department declared war on the city's black population. Police broke into scores of homes without warrants or the slightest pretext of probable cause. The search teams were called "flying squads," as delicate a euphemism for police state terror as it should ever be our disgust to encounter. Juanita Jackson Mitchell had to take city police to federal court and remind them that Baltimore was in America, not Nazi Germany or the Stalinist Soviet Union. As a young boy living in the Murphy Homes housing project at the time, I vividly remember wondering whether I had more to fear from the Veney brothers or the Baltimore Police. Years later, I remember thinking that whatever the iniquities of the Veney brothers, it was their act that exposed the Baltimore Police Department for its brutal, racist treatment of Baltimore's black citizens in 1964 and before. Should we forget how bad it was, we need only remind ourselves that Commissioner Donald Pomerleau—hardly a flaming liberal—was brought in to nudge the department into the 20th century. Now Sam Veney comes back to haunt us again. It seems that every time Veney screws up, a larger issue is brought into focus. The issue this time is the parole policy of the state of Maryland. Many were wondering—Evening Sun columnist Dan Rodricks among them—why a lifer like Veney, who was not being considered for parole, was given weekend home visiting privileges. I'm sure Sam Veney looked at the situation differently, as did his family. He figured that with a good behavior record and a 10-year history of returning from weekend visits, why shouldn't he be considered for parole? So old Sam simply initiated self-parole. And to give the devil his due, Sam Veney has a point. Yes, he killed a cop. Yes, he was given a life term. But everyone in the state knows that some murderers are given life terms and then are paroled. Others, like Sam Veney, are given life sentences and won't ever be considered for parole. The criteria for determining which murderers get paroled and which do not sound good—the prior criminal record, the impact on the victim's family, the convict's progress while in prison—but ultimately lead to charges that the race, class, and occupation of the victim come into the equation. How is it that Sam Veney can see the absurdity of such a policy and we civilized, law-abiding citizens can't? All murder victims are equally dead. There are none deader than others. If some lifers have a shot at parole, all should have a shot. Or none should have a shot. Equally absurd is the case of Terrence Johnson, sentenced to 25 years for killing two Prince George's County police officers. Johnson has been a model prisoner for years, even taking the time to further his education while in prison. But don't look for him to be paroled. Gov. William Donald Schaefer found the heart to pardon women convicted of killing husbands and boyfriends on the grounds that the women had suffered brutality at the hands of the men. Even though the prosecution in Johnson's case conceded the cops were brutalizing him at the time of the killings, the governor apparently can't see any justification for granting Johnson not a pardon but parole. We ought to be concerned that Maryland law allows for the parole of murderers given life sentences. As former city police commissioner, state public safety commissioner, and current Mercy Hospital brain surgery patient Bishop L. Robinson has pointed out, if we don't want murderers paroled after they've been handed life sentences, we need only express our wishes to our state legislators and get them to work changing the law. Let's put a no-parole-for-lifers law on the books. Paroling some murderers and denying parole to others puts a price tag on that which should be priceless: human life.

ex-officer remembers Veney raids held in 1964

June 9, 2001 | By Gregory Kane

Some curious readers have asked: What were the Veney raids?

I'm older than I'd like to think. At one time, most Baltimoreans knew what the Veney raids were. As those of us in the baby boomer generation get older, we assume those younger know what we know. We assume that events from December 1964 are common knowledge. But they aren't. Sam and Earl Veney robbed a liquor store in December 1964. The two black men also shot two police officers, killing one. They were caught and convicted. But the police manhunt in Baltimore for the Veney brothers became almost as infamous as their crimes. Without warrants, police broke into scores of homes in black neighborhoods. (Some put the number as high as 300.) Some critics protested that the raids were a widespread violation of civil liberties. Federal courts and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People had to get involved. In a recent column, I referred to the Veney raids as "notorious." One man who remembers the raids well—much better than 13-year-old Gregory Kane could have—took umbrage with the use of the word. He's Paul Lioi, now retired and living in Florida. In December 1964, he was 25-year-old Officer Paul Lioi of the Baltimore Police Department. He sent this letter to The Sun: "That [notorious] remark hit a sensitive chord with me," Lioi wrote. "Let's go back to 1964. It was Christmas Eve, and the children of two police officers wrapped their fathers' gifts and went to bed. They could hardly wait until morning when their daddies would return home from work to open their gifts and celebrate Christmas together. This was not to be because one daddy, a police lieutenant, was shot and wounded during a hold-up at a liquor store on Greenmount Avenue. "And later that same day, the second daddy, a police sergeant, was killed. Neither family celebrated Christmas that day, and for one family, Christmas and every day thereafter, the dad would no longer be with them. The investigation at the robbery scene revealed that the suspects responsible for the robbery and shooting of a police lieutenant were the Veney brothers. As the police went looking for the brothers, one of them shot and killed a police sergeant. Two police officers shot, one seriously wounded and one killed. They happened to be my lieutenant and sergeant. "The police department went on a manhunt to try and locate and apprehend these police assassins, known as the Veney brothers. They felt compelled to follow up on any lead they received. The tips they received came from the black community. I was part of the raiding party and felt that the tips received were authentic." 37 years later, and Lioi, who won four Bronze Stars, a Distinguished Service Medal, and the Medal of Honor in his police career, knows that many of the tips were nowhere near authentic. "Most turned out to be bogus," Lioi said yesterday from his Orlando home. The reason baffles him. This was a search for cop-shooters. "Why," Lioi wondered, "were they giving us these bogus tips?" Lioi also feels empathy for those who lived in the raided homes. "Come to think of it," he said, "it was a bad thing. We had our guns pointed at the houses. We weren't going to walk up to a suspect and say, `Sir, are you Mr. Veney?'" Lioi says he arrested one of the Veney brothers—he doesn't remember which one—several months before that fateful Christmas Eve. He and his partner, whose regular beat included the liquor store that was robbed, were off the night the store was robbed. He often wonders what would have happened if they had been working instead of Lt. Joseph Maskell, who was wounded in the liquor store robbery, and Sgt. Jack Lee Cooper, whom Sam Veney fatally shot after Cooper confronted him in East Baltimore. "He was a decent guy, a real gentleman," Lioi said of Cooper. "His death just about ruined my Christmas. I went up to my room and closed my door because I didn't want my children to see a grown man cry. And I did." Other memories of his East Baltimore beat are happier. He remembers when he was "fighting some mental case" and, unable to call for assistance, finally received it when concerned residents called for him. And he became a fan of legendary black comedian Jackie "Moms" Mabley while walking his beat on the graveyard shift. "It was about two in the morning," Lioi recalled. "I was walking by this house, and the door was open. I heard a comedian doing a routine." He listened a bit and was delighted to hear one of the funniest comedians he'd ever come across in his life. A woman who lived in the house told him who it was and where to buy the album. The next day, Lioi was in a store on Greenmount Avenue, buying it. When his beat-walking days were over, he was promoted to sergeant and later became a detective with the arson squad. He retired in 1984 after 23 years on the force. Lioi offers no apologies for his role in the Veney raids. It was mischievous tipsters, he insists, who were responsible. But that may be why the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals was critical of the raids. Federal judges realize that any crackpot can give a tip and lead even good cops to do bad things.

I read both stories and on the one hand, I applaud (if you can applaud with one) the work of G Kane for telling the story, but to compare a traffic violation with a cop killer and the laws and rules of 1964 Baltimore to 1992/93 LA is wrong; in one case, no one was killed and several officers lost their jobs, as they should have. But what happened in 1964 Baltimore involved, as Officer Lioi explains, the public dropping bad tips to get police reaction. In 1964, Baltimore Police didn't have body armor, so when they had to go in after suspects who had shot one officer and killed another, ringing the doorbell was out of the question. It is so easy to sit back and watch Monday morning quarterback what people do for a living; in some cases the public forgets police get killed, they die and there is no reset button. The public demands protection from their police, and in 1964, the Veney Brothers were bad news, so to send police in after two brothers that they knew will kill them if given the chance, police did what they had to and were trained to do in order to protect the public. Keep in mind that was 1964, if that were today, then of course it would have been done differently, heck, if it were 1992/93, it would have been handled differently. But let's face it, it wasn't today; it wasn't 1992/93 and things were different back then, To compare cop killers to traffic violation is wrong. The police reaction in one case was to stop and arrest a suspect for poor driving; the other was to bring in two cop killers and go home alive. To compare the two is more than apples and oranges; it is disrespectful to the families of these officers and every officer who has had or has since put on the badge. If there were cop killers in my neighborhood hiding out, the police wouldn't have to kick my door in; they would be welcomed to come in and check anytime. So often, the public become so discontent with police that they will find fault in their every move, even things that happened before the officer they are dealing with ever set foot on the job. But what they don't realize is that every officer on the job risks his or her life every time they go to work, and they do it so we can be safe. If people would cooperate with police and call when they see something wrong, not call in for jokes or to have a neighbor they don't like raided,. All neighborhoods would be equal. But that's just my opinion.

Robert F. Kennedy said, "Every society gets the kind of criminal it deserves. What is equally true is that every community gets the kind of law enforcement it insists on." According to the false tips 1964 Baltimore put up, it's not income that has some criminals living in some areas over others, nor is it income that increases the number of police in an area. In fact, most good neighborhoods have less police than some of the worst neighborhoods. So how does this work, Why does it work like this, Because in better neighborhoods, when someone hangs on the corner, the police are called, people chased off, etc. If someone is holding a gun, police are called and before long, people stop holding guns in that area or hanging on the corner. Basically, cooperating with police and letting them know who is doing what and where will get people out of certain areas. At a meeting in Baltimore County, we were told that if we want more police, we have to call the police more often when we see crime, but if we are not seeing crime, then more police won't be needed. And in my neighborhood, if kids hang on corners, police are called. If someone steals a bike, the police are told who took it and where they put it. Police aren’t mind readers; if we want our neighborhoods safe, we need to report what we know; if we don't, we'll end up with that type of criminal living in our area (we welcome them by not letting police know they are unwelcome). The more we cooperate with police, the better quality police service we'll have too. Bobby Kennedy may have been onto something.

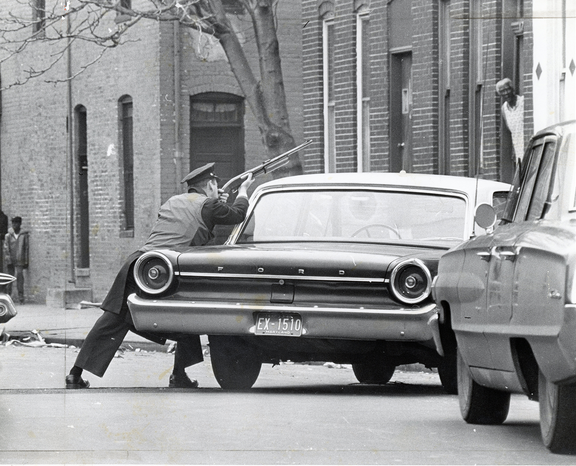

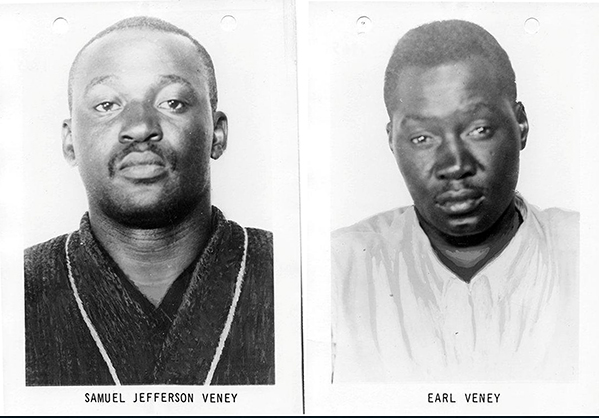

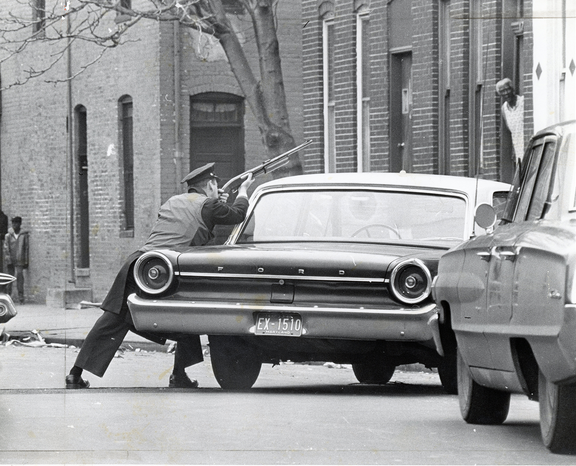

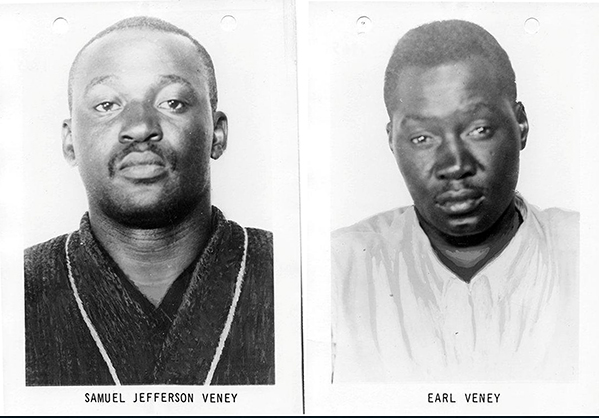

Photos Courtesy of Nick Caprinolo

Photos Courtesy of Nick Caprinolo

The photos came to me courtesy of Nick Caprinolo. I'm not a big fan of showing pictures of the suspects in these type cases, but in this instance, the suspects have gained a sort of finger pointing at the police, as if we did something wrong in getting them off the streets. So I think it may be appropriate to show these suspects were not mellow or meek-looking individuals that were being picked on and singled out by the Police. They were two brothers that regularly robbed individuals in the area as well as many A&R's at the neighborhood liquor store. When police went to arrest them, they shot a lieutenant first, then later in the same night, they shot and killed a police sergeant.

As a result of their actions and the discontent of these brothers by the neighborhood, hundreds of tips came in to police hot lines giving information on the two, Sometimes the tips were false, sometimes they were real. But it was out of fear of the Veney Brothers, not the police, that the tips were brought in.

When I post these stories here, I often follow-up on Facebook, where I receive different responses, and those messages tell us a lot too. Here are some of those responses:

The first response was, Many of those bogus tips were on purpose. The brothers were caught in New York and weren't in Baltimore for most of those tip calls! Those "tips" led to the greatest violation of the 4th Amendment ever, according to one Federal judge.

The next response was, Thanks for posting these.

My response to the first response was as follows: The thing about the "Veney raids" is the officers that were making entry and doing the raids were doing it in good faith; they didn't know the tips were bogus, nor did they know where the brothers were. Something people don't understand about police is that they don't want to do a raid just to do a raid; no one wants to go into a home, disrupting lives of good people, knowing the suspect(s) or suspected objects are not in the house. Since 1964, a lot has changed: police equipment has changed, Communications is different, and the way information is obtained has changed drastically. Back then, when I was 6 months old, I wasn't sworn in with the BPD yet, so the only thing that is the same for me from then to now is I couldn't walk back then either. If people only knew the amount of pride officers have in getting the suspect, not one officer would want to waste time chasing bad leads. So yes, I agree there were problems with the raids, and today those raids would have been done much differently. But let's not forget, every one of those raids was done in good faith by police that knew if they were the one that got the house Sam or Earl were in, they may not have made it home, but they still did their job and went in after them.

Someone who was there at the time wrote the following about my response: As a Baltimore Police Patrol Officer at that time, I participated in many of those raids. I served in the area where the robbery occurred and worked with both the Lieutenant and Sergeant that were shot. Thank you, Kenny, for your posting and explanation of the circumstances that existed at that time.

A good friend of mine who worked the district of this shooting wrote, I heard many tall tales about this.

another writer, Kenny, I remember the night well. The entire Western shift volunteered, as did most of the other districts, to work many "unpaid" hours. We knocked down lots of doors without warrants and dragged numerous suspects in, but were unsuccessful in locating them. The FBI detained them in New York several weeks later. Here again, the police were trying to get the Veney brothers—trying to make the area safer and, most importantly, doing what they were ordered to do. But they did volunteer (unpaid) in order to try to get these guys, to try to make the arrests that would get two murders off the streets, and to make the streets safer. They didn't want to do it—just to kick in doors, just to drag suspects into the station. If you knew the pain in the rear end it is to transport prisoners or witnesses to the station, you would know the only reason any one would do at all, much less for free, is because they were trying to help! The times were different than today, and if they had it to do all over, they would do it differently, but they would still have to remain cautious and do all they could to make sure they went home alive and no one was injured or killed. Finally, I was attending Edgewood Elementary School at the time. I remember the fear people had and the relief they felt when they were caught. Parents were afraid to send kids to school. Very good piece, Kenny.