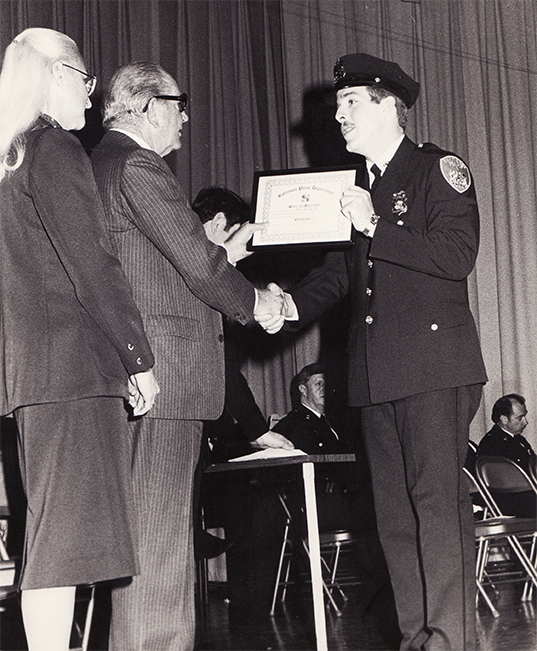

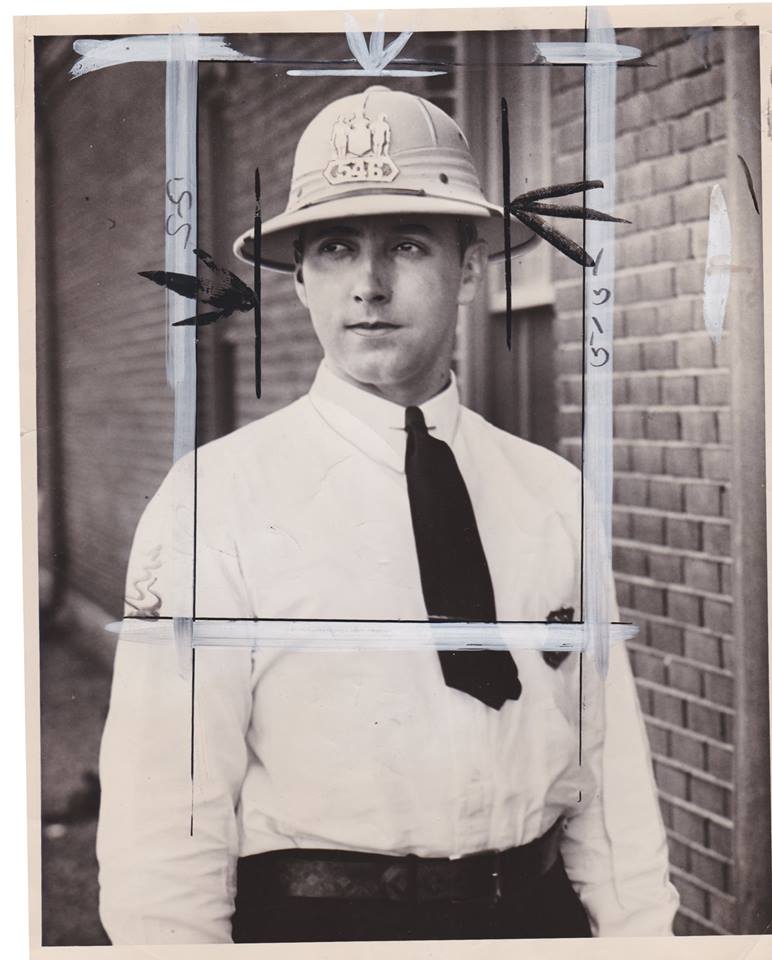

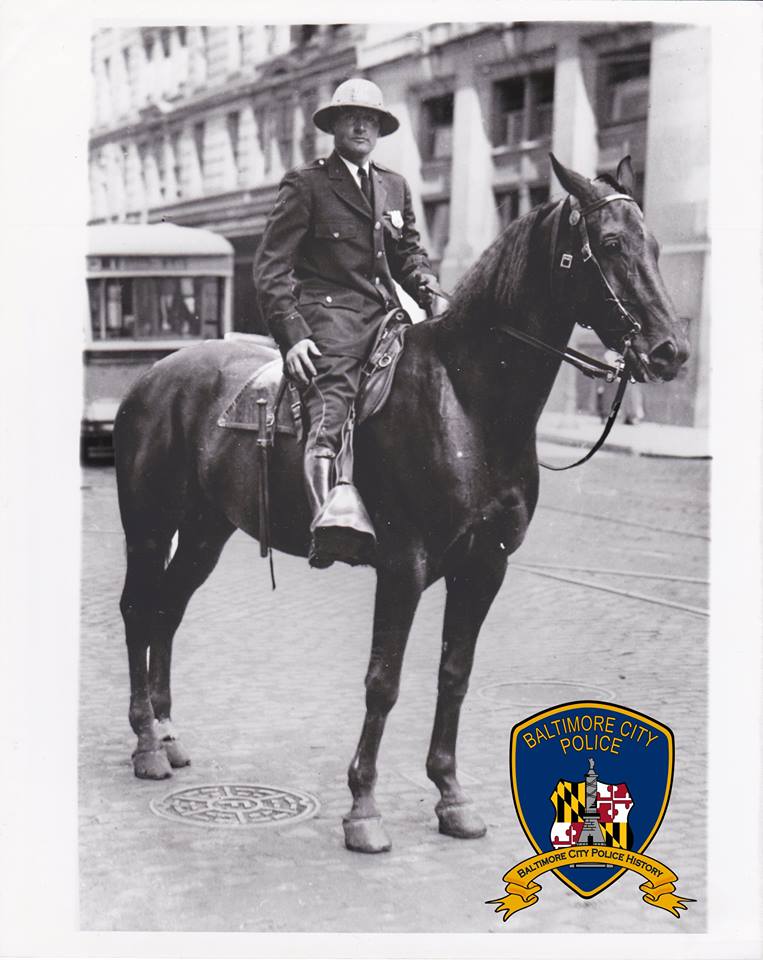

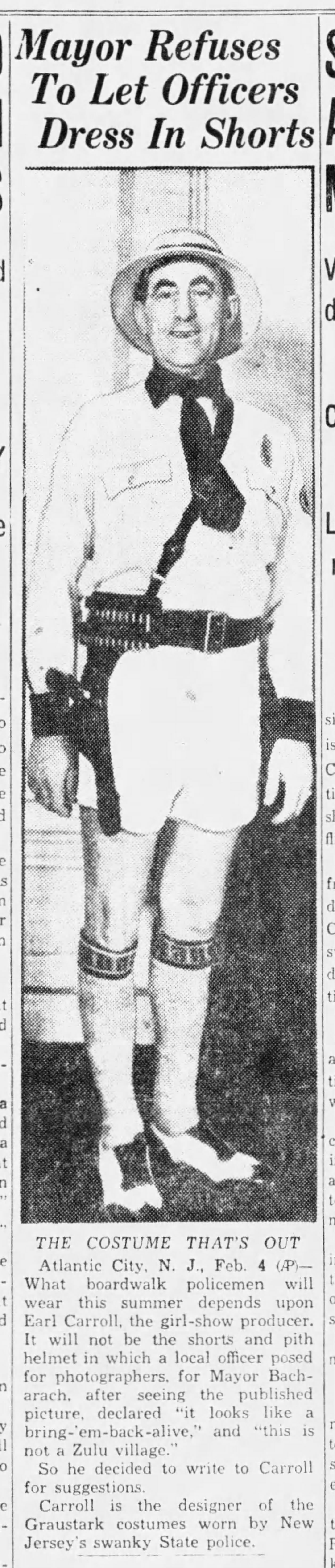

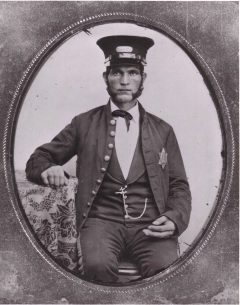

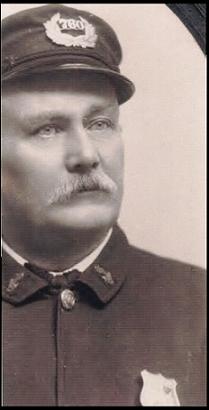

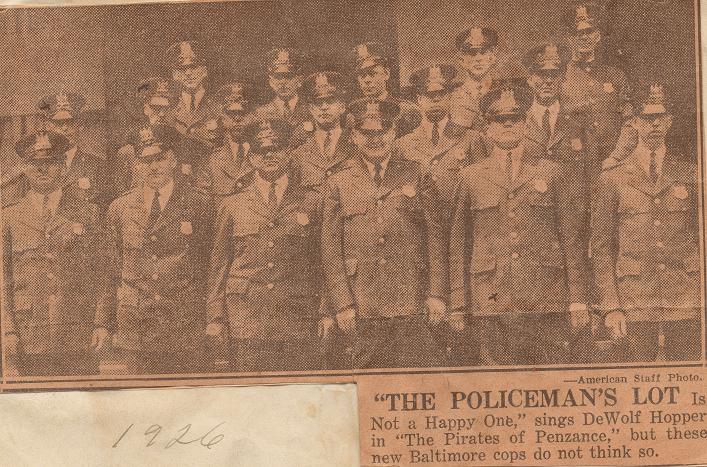

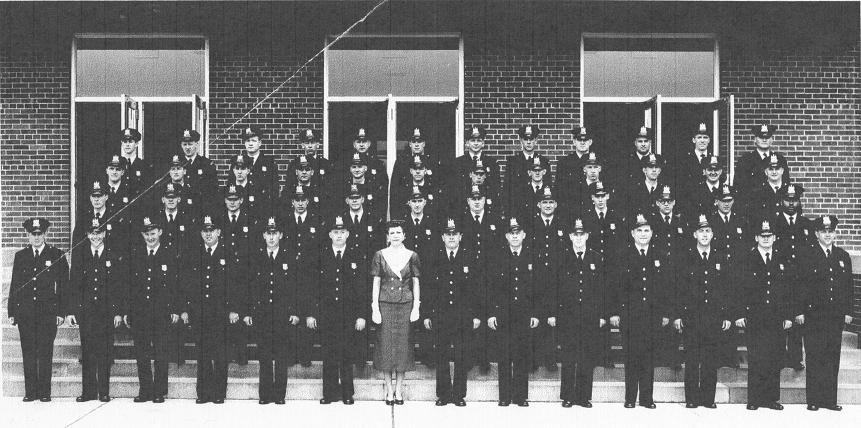

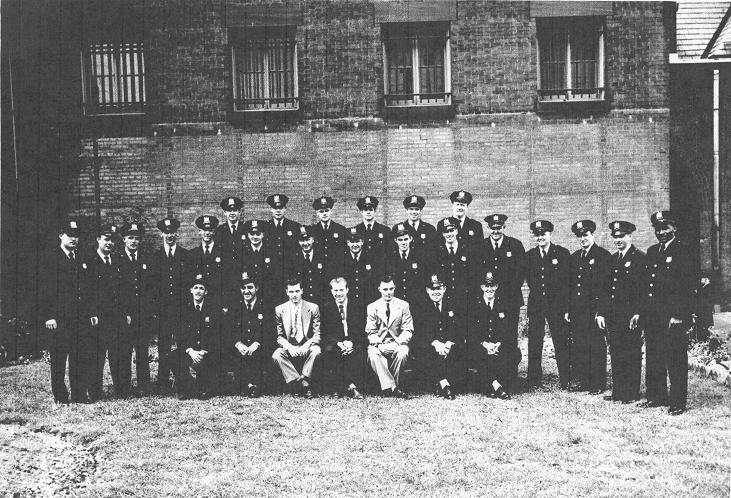

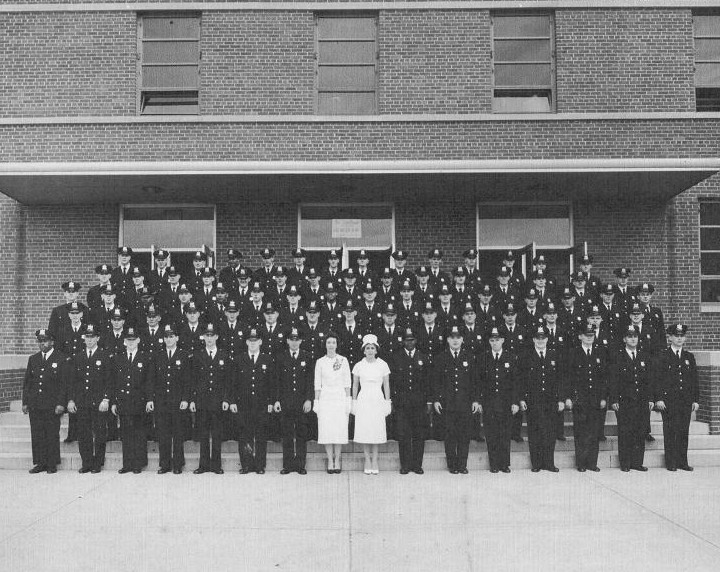

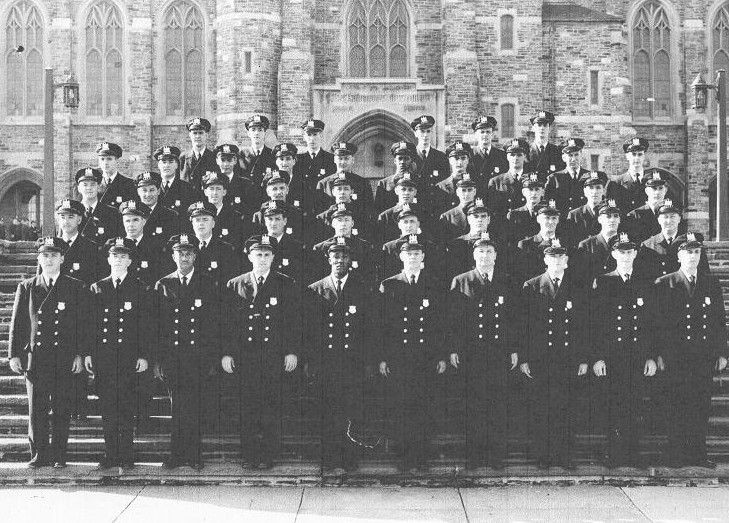

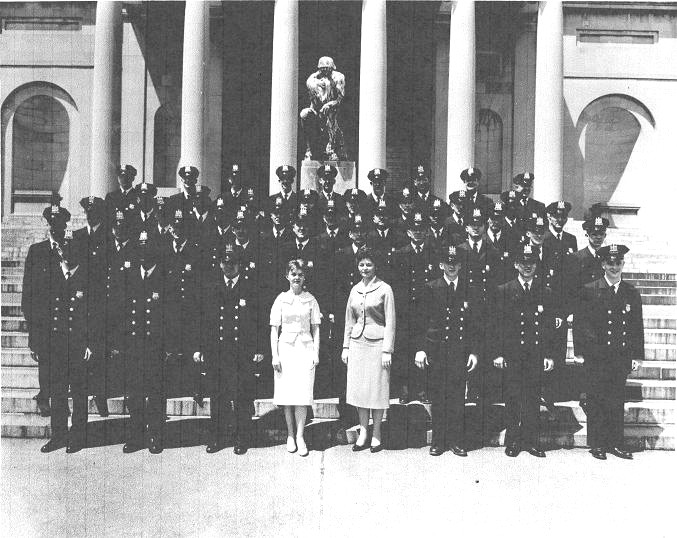

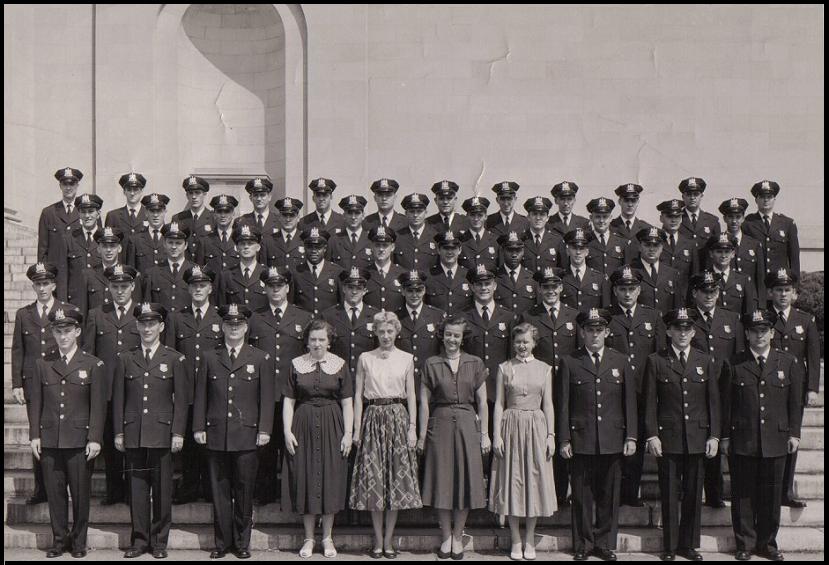

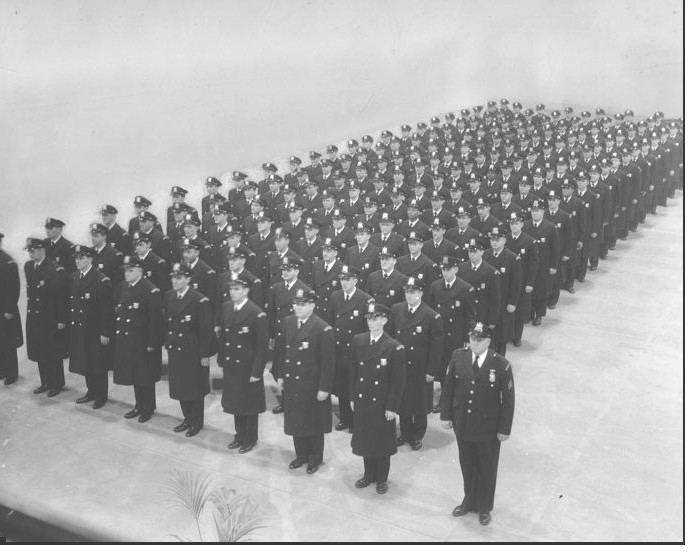

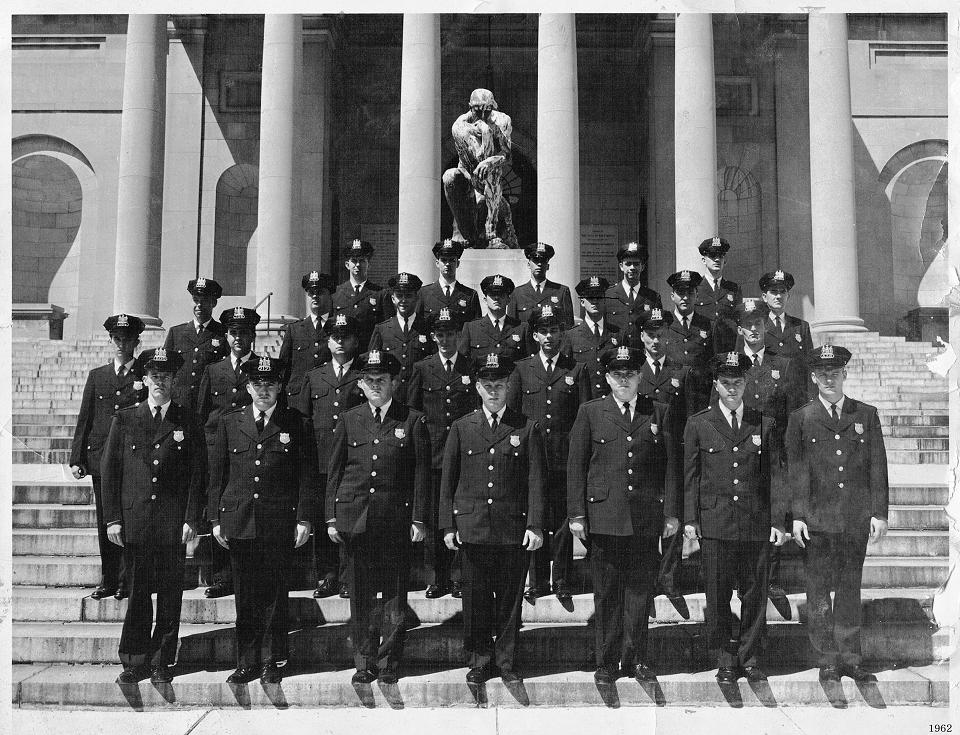

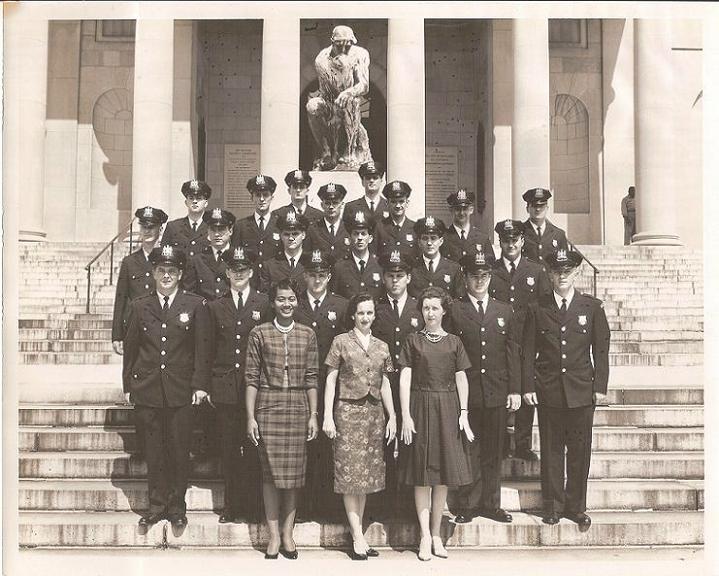

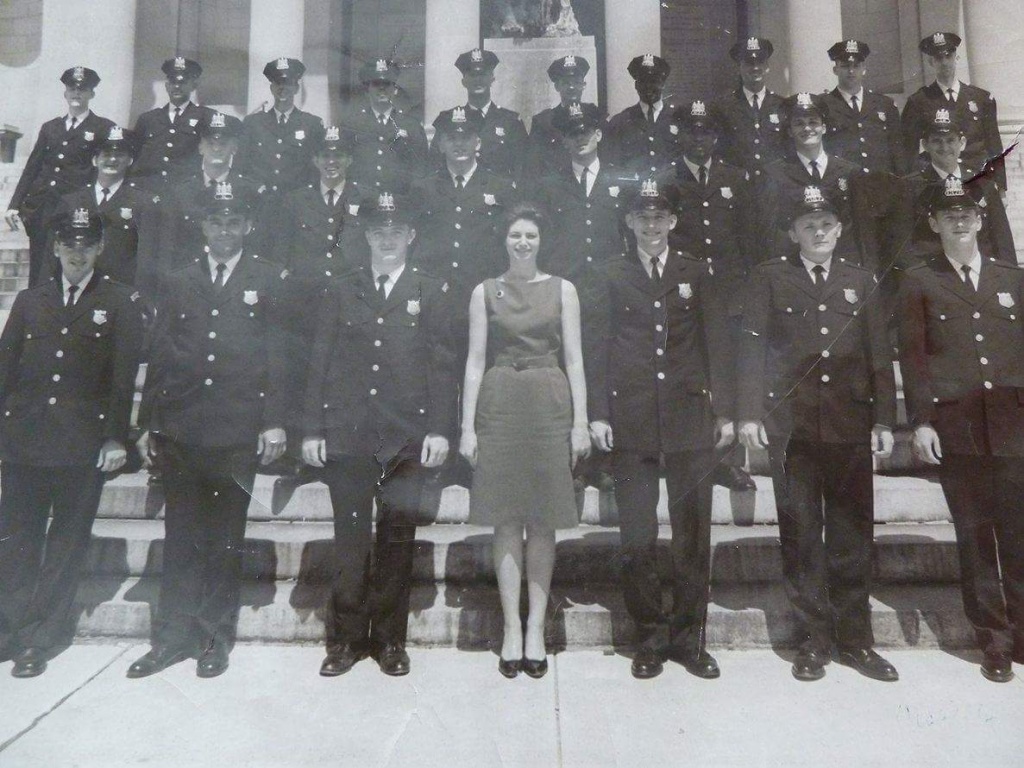

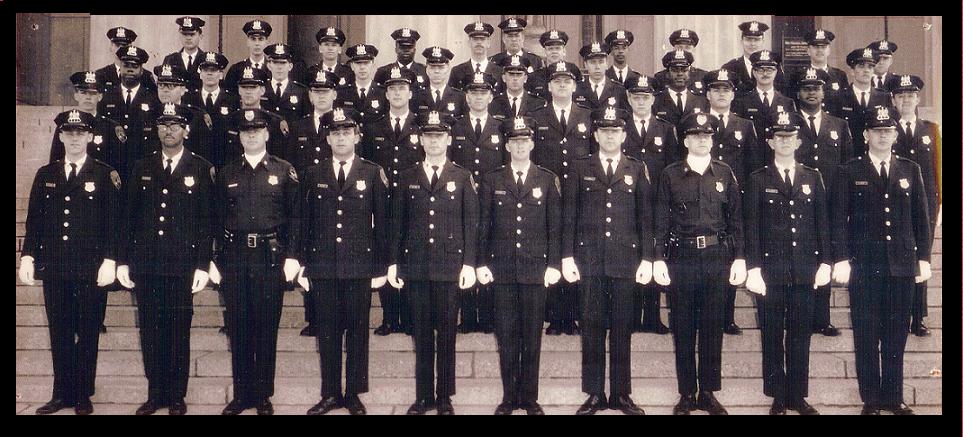

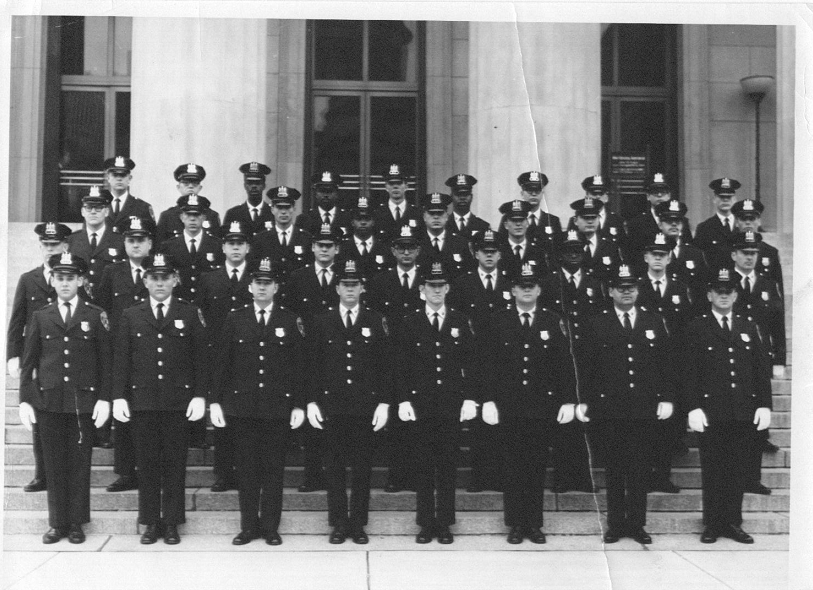

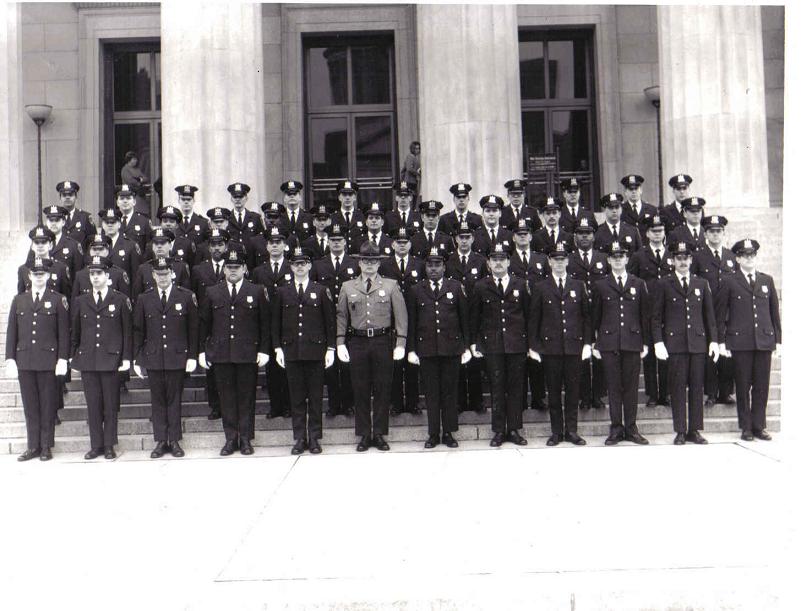

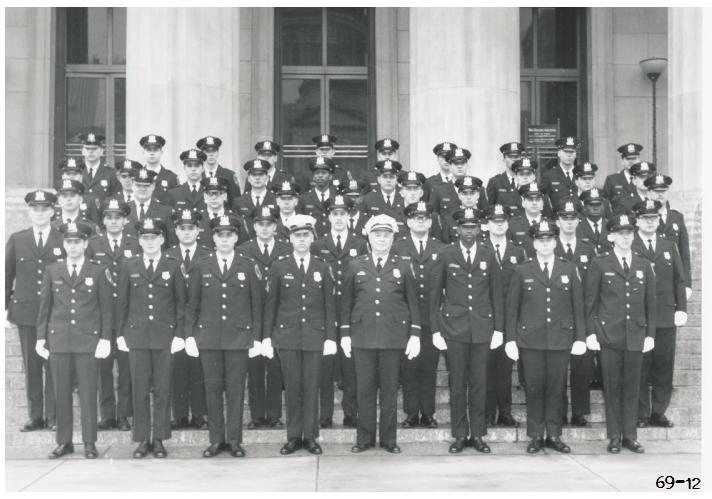

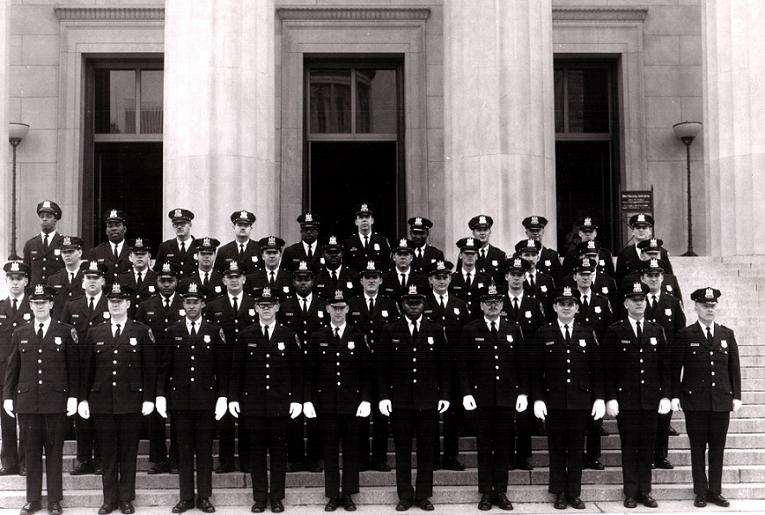

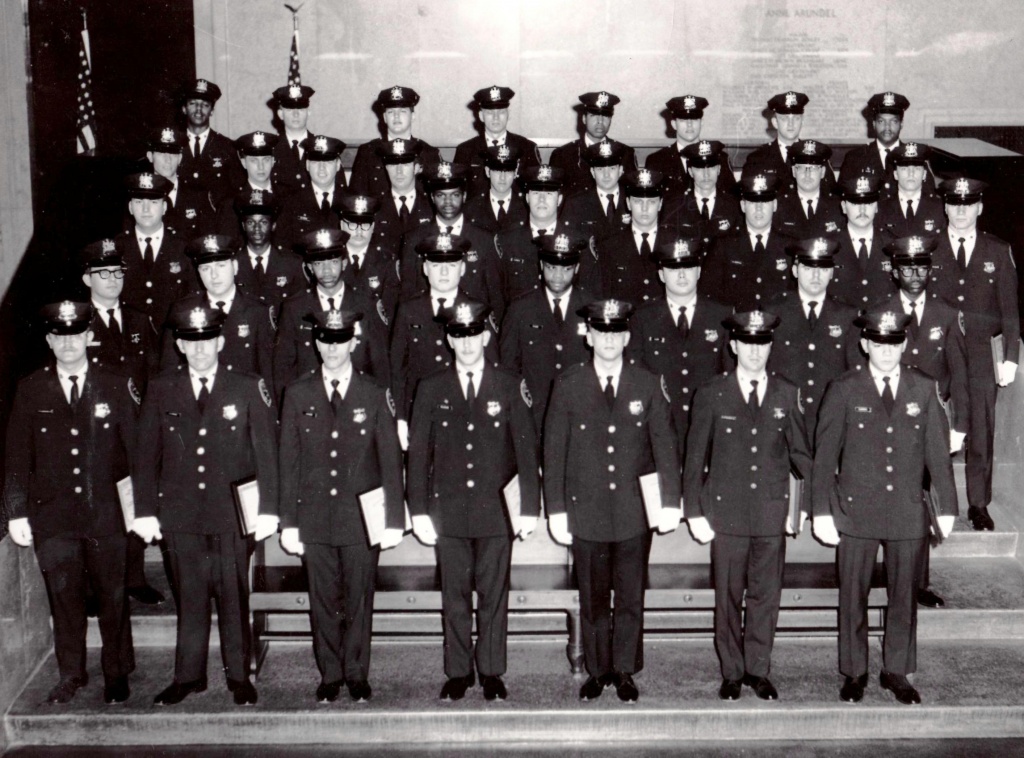

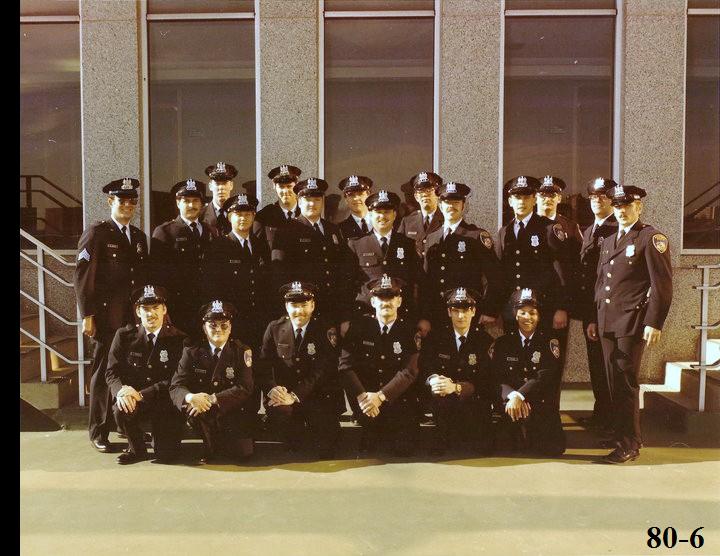

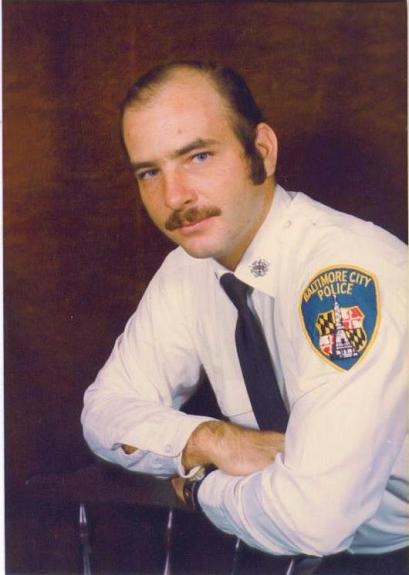

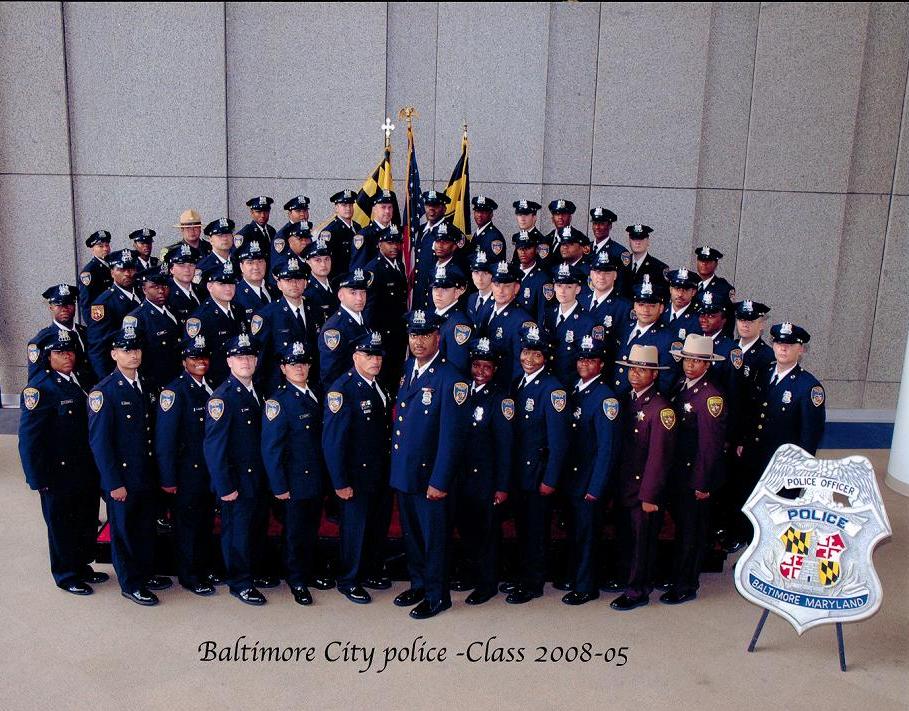

Notice - The Hat Device has the State flag, Helm and Officer's badge number

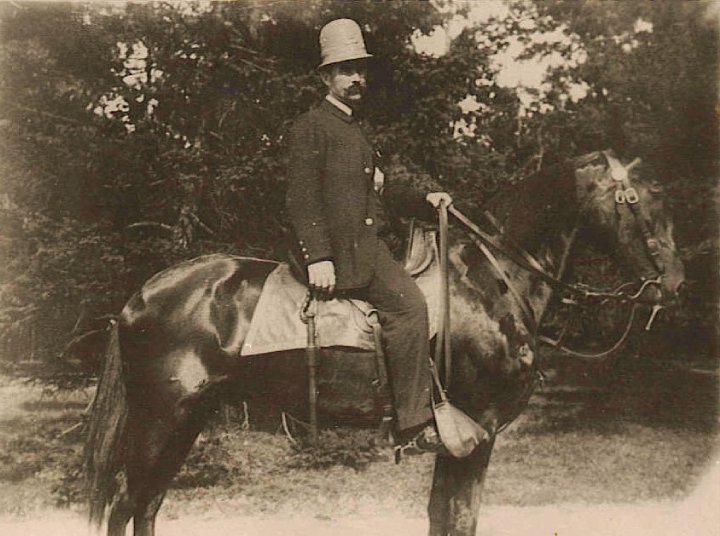

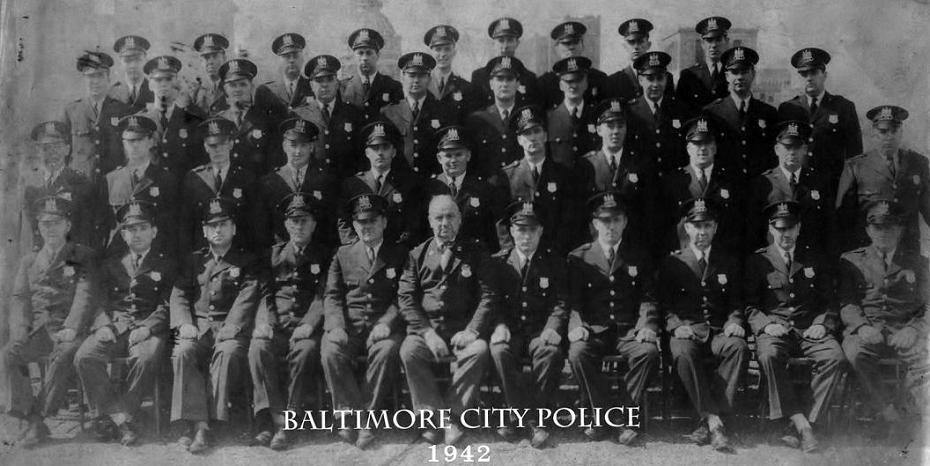

A clear sign that this came after 1908 and was take between 1908 and 1944

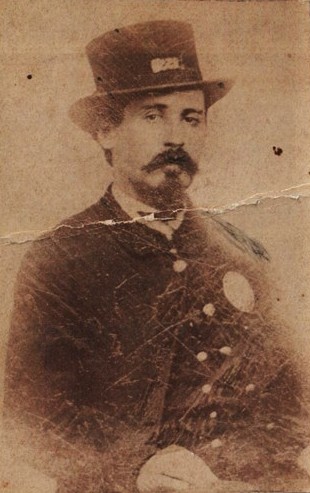

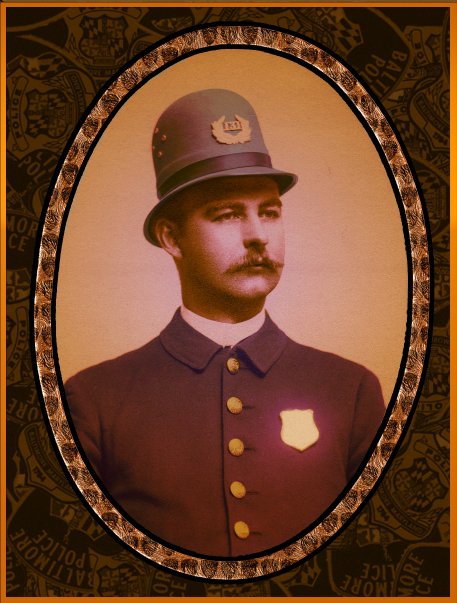

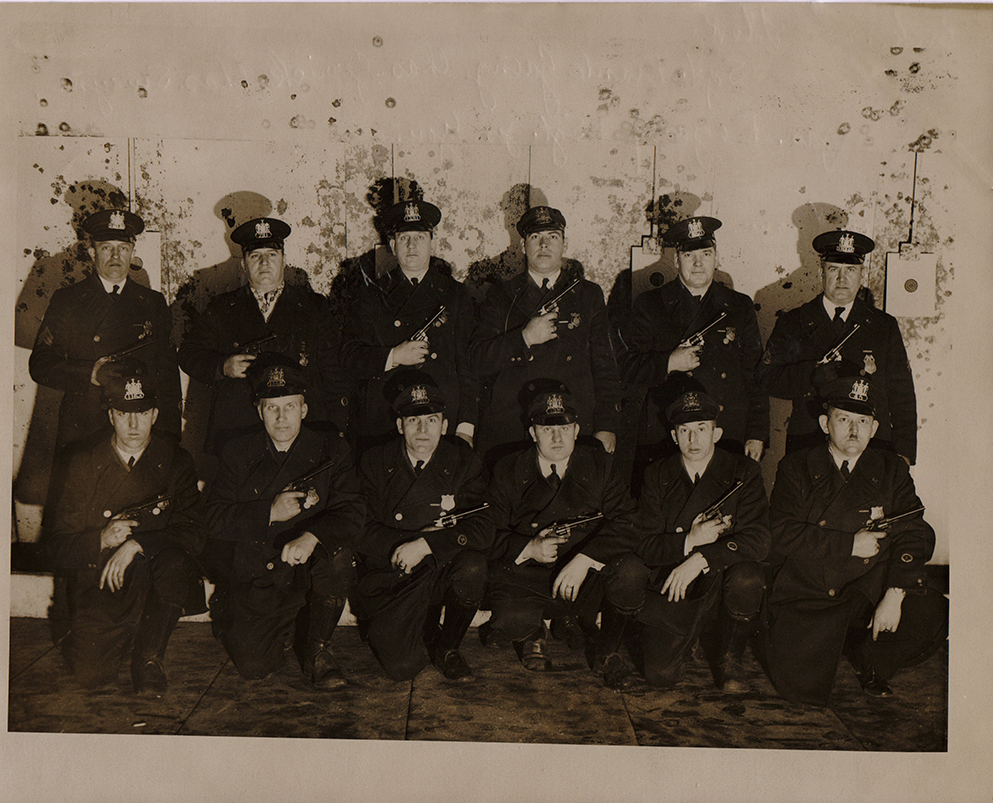

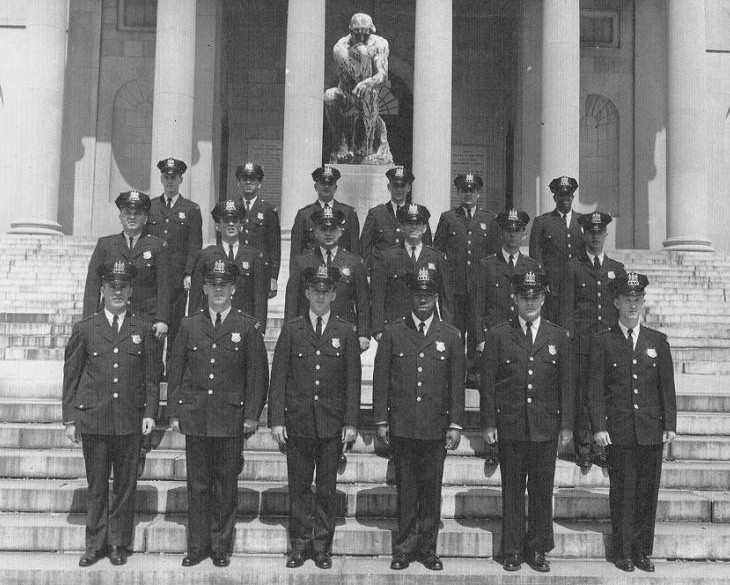

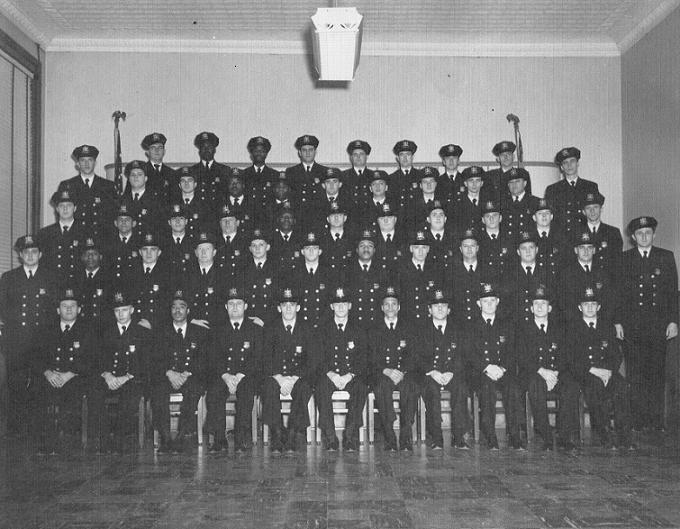

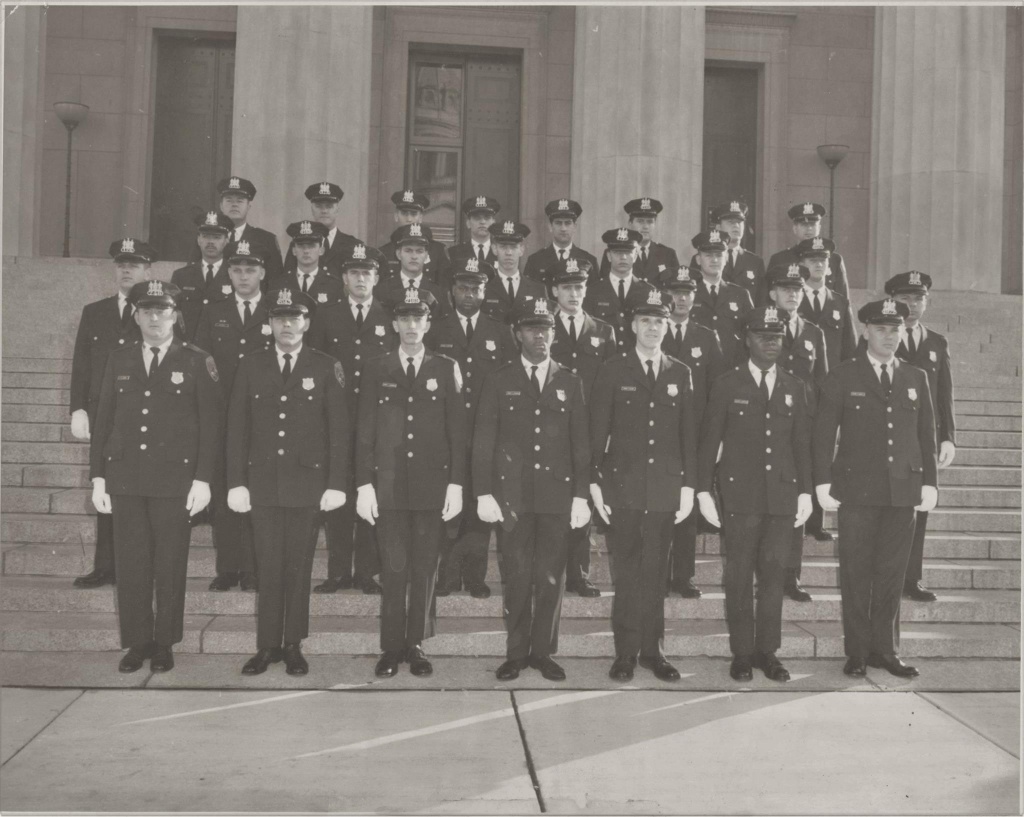

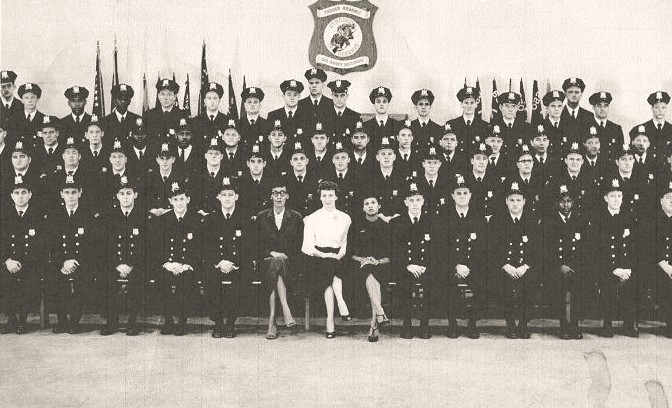

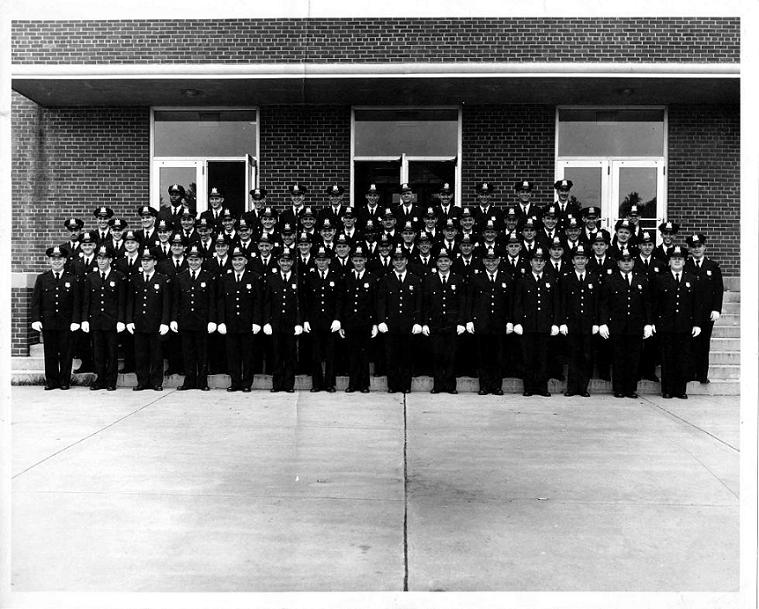

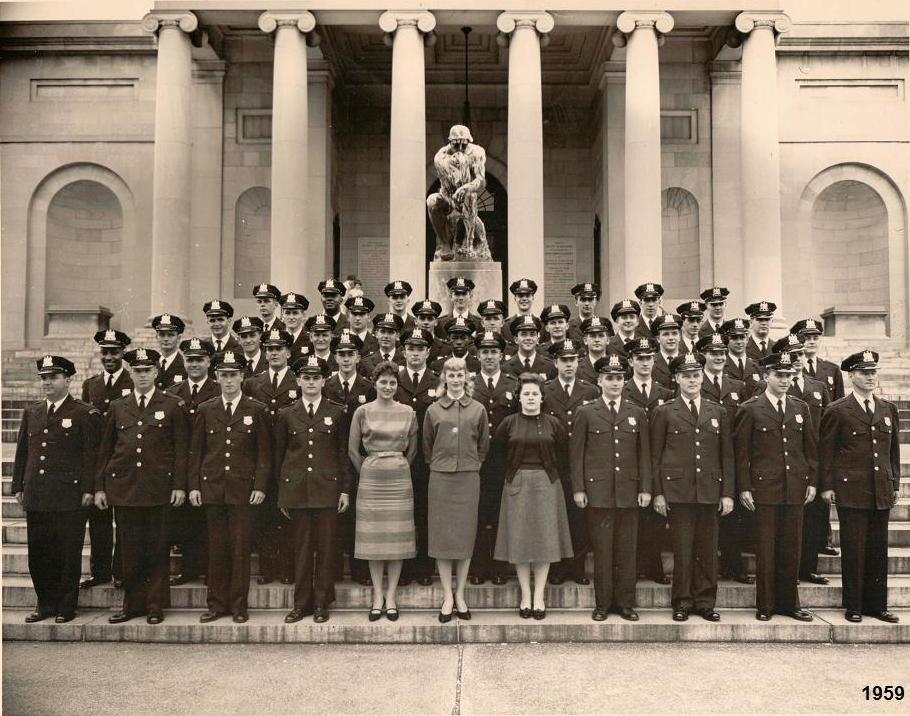

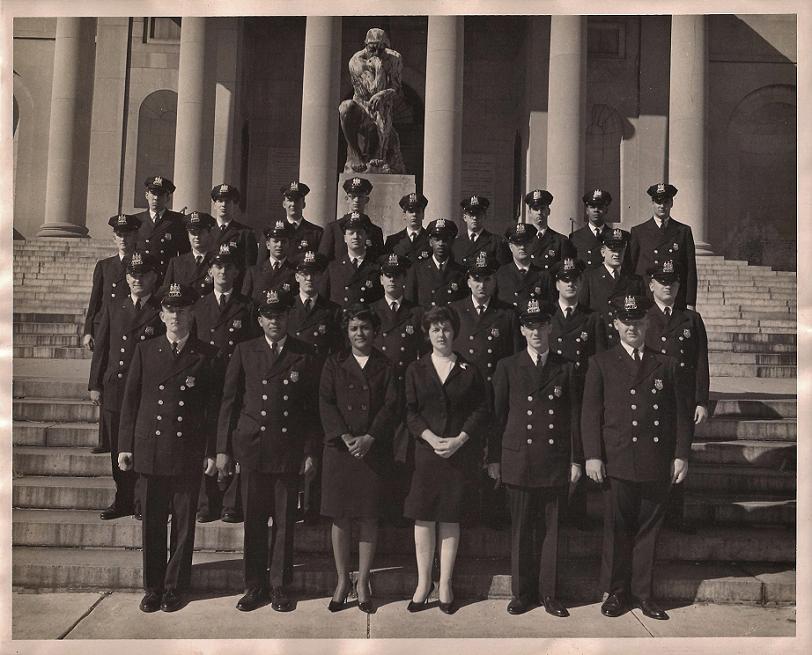

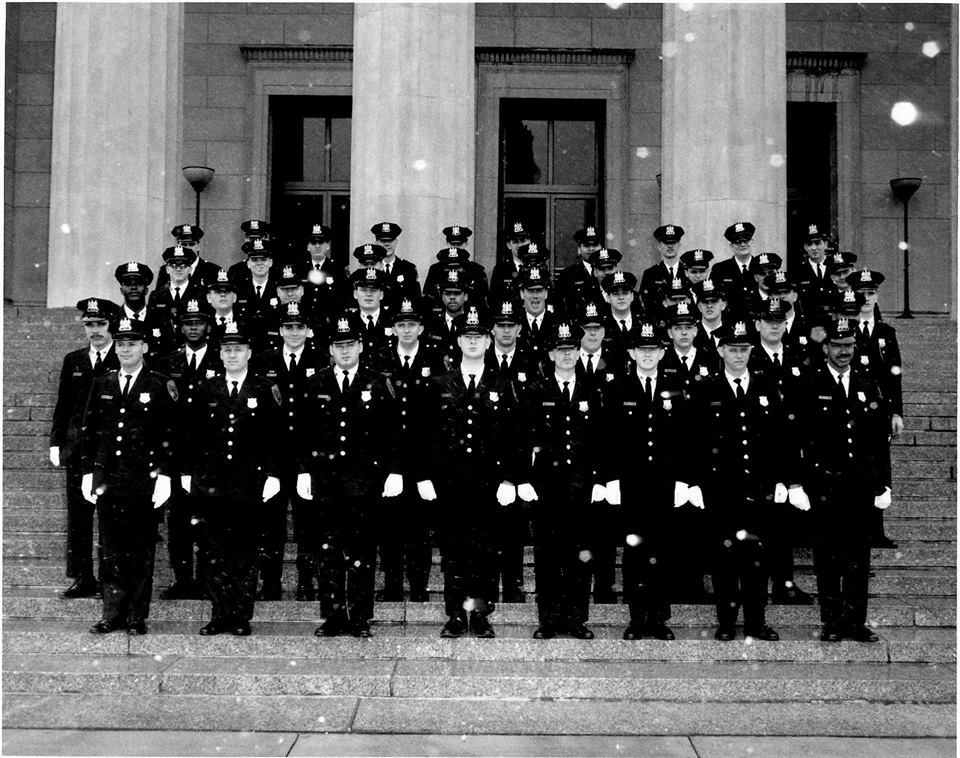

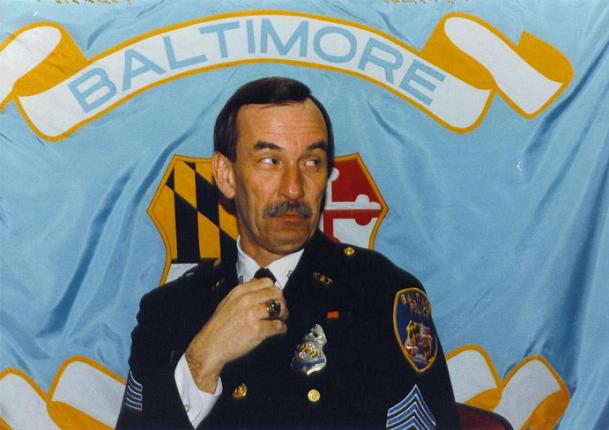

1944 and after

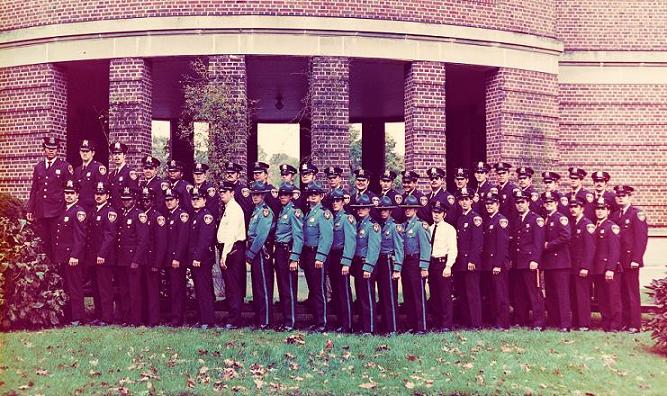

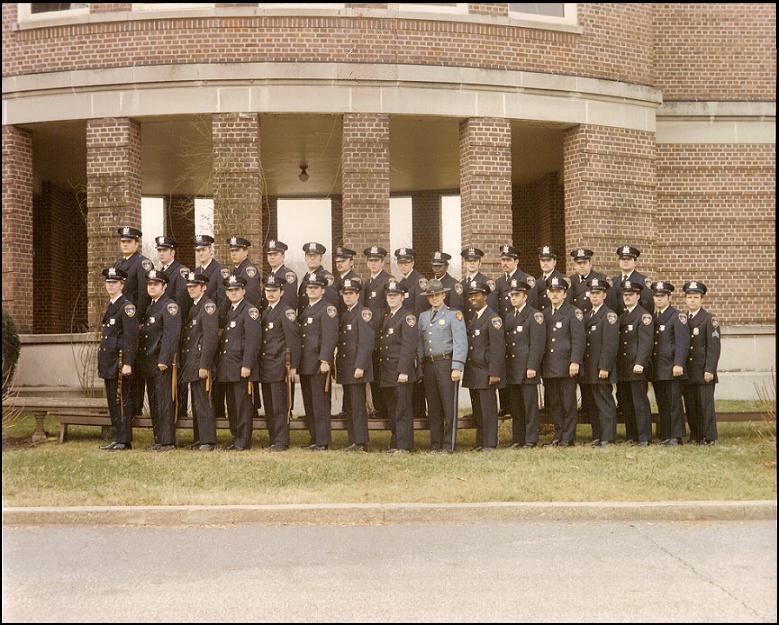

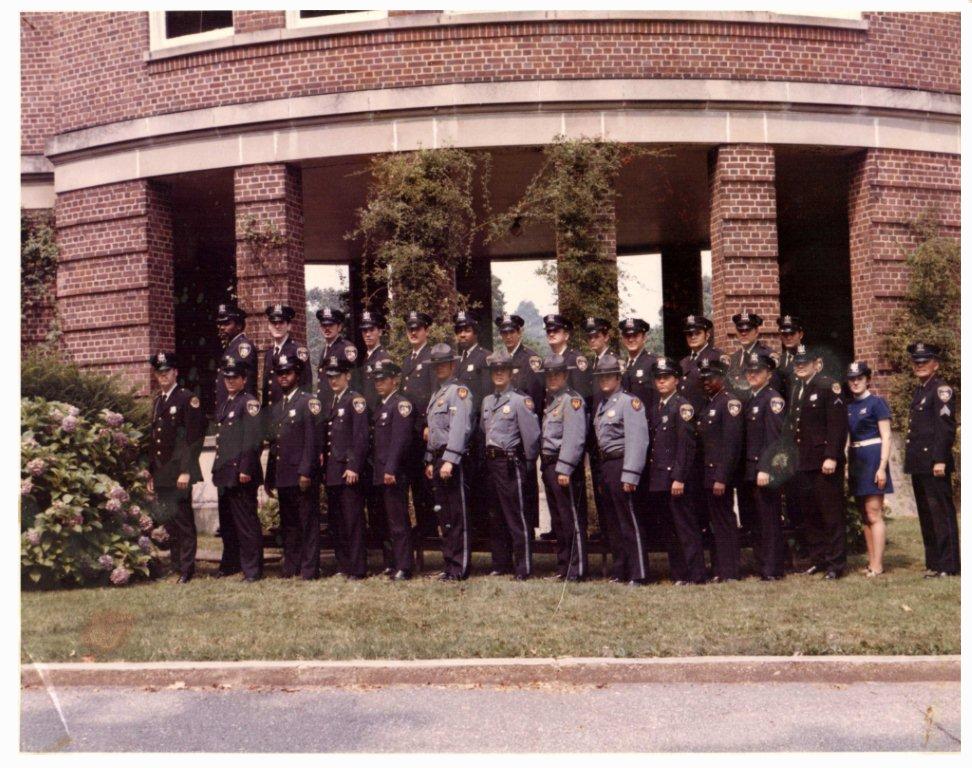

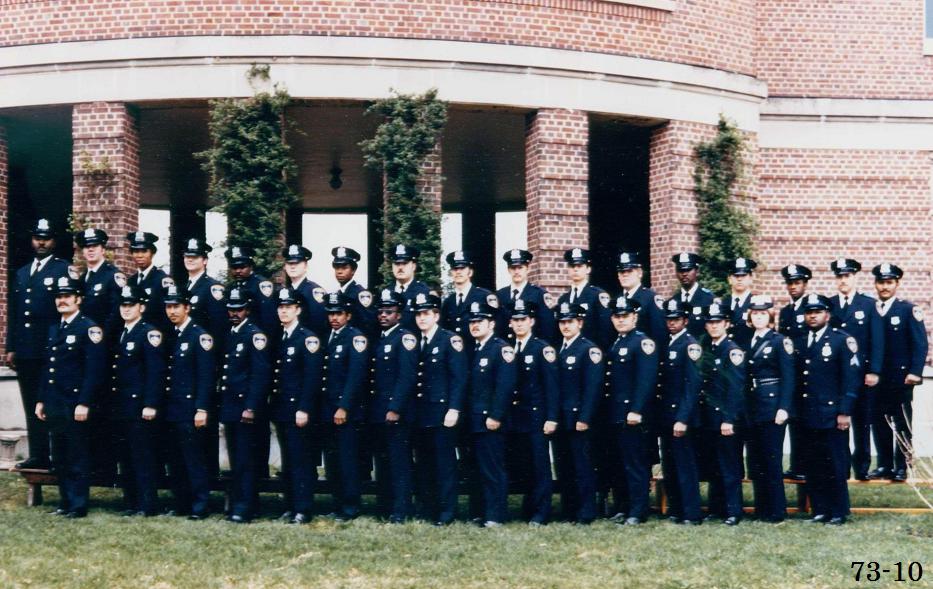

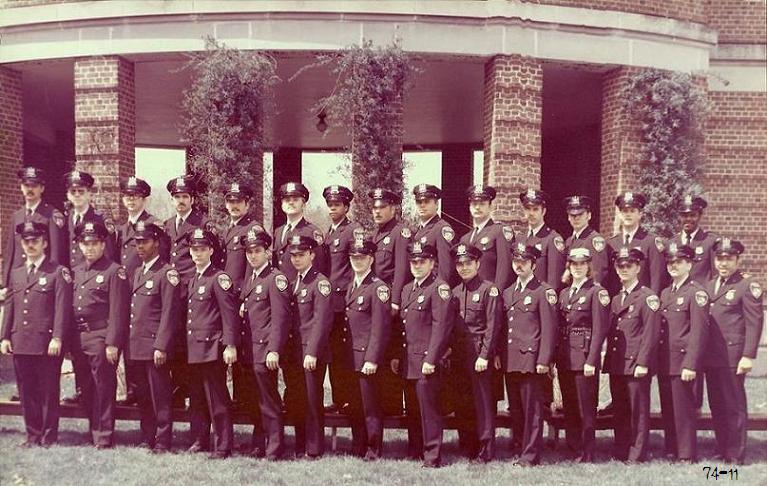

1944 - 7 October 1944 - The Baltimore police switched from the round, or oval top police hat/caps that were worn for a little more than 30 years after the "Bobby Cap" type helmet, to the current "Octagonal" or "Eight point" hat we wear today.

OUR BADGE COLLECTION

OUR PATCH COLLECTION

BPD PATCHES

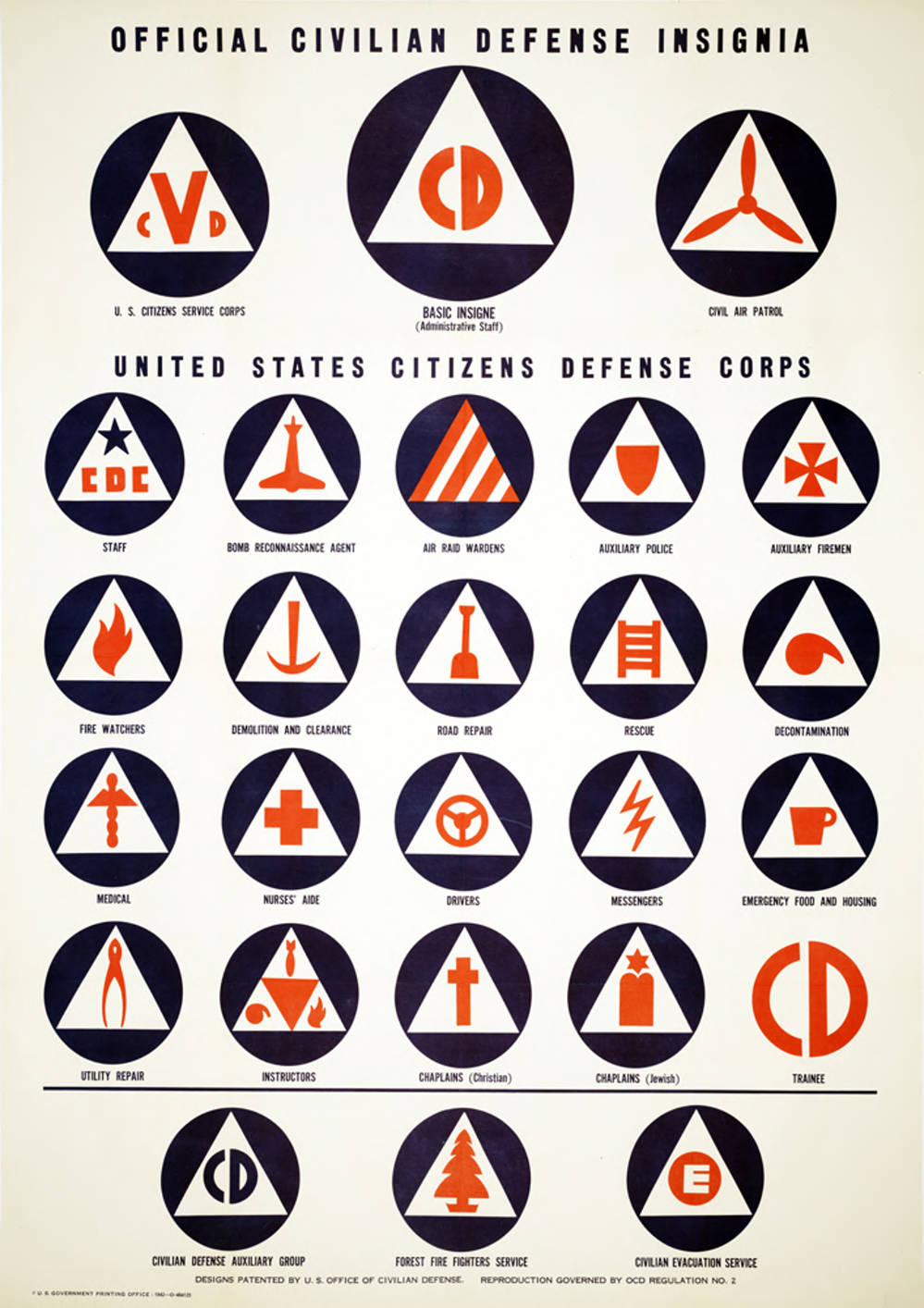

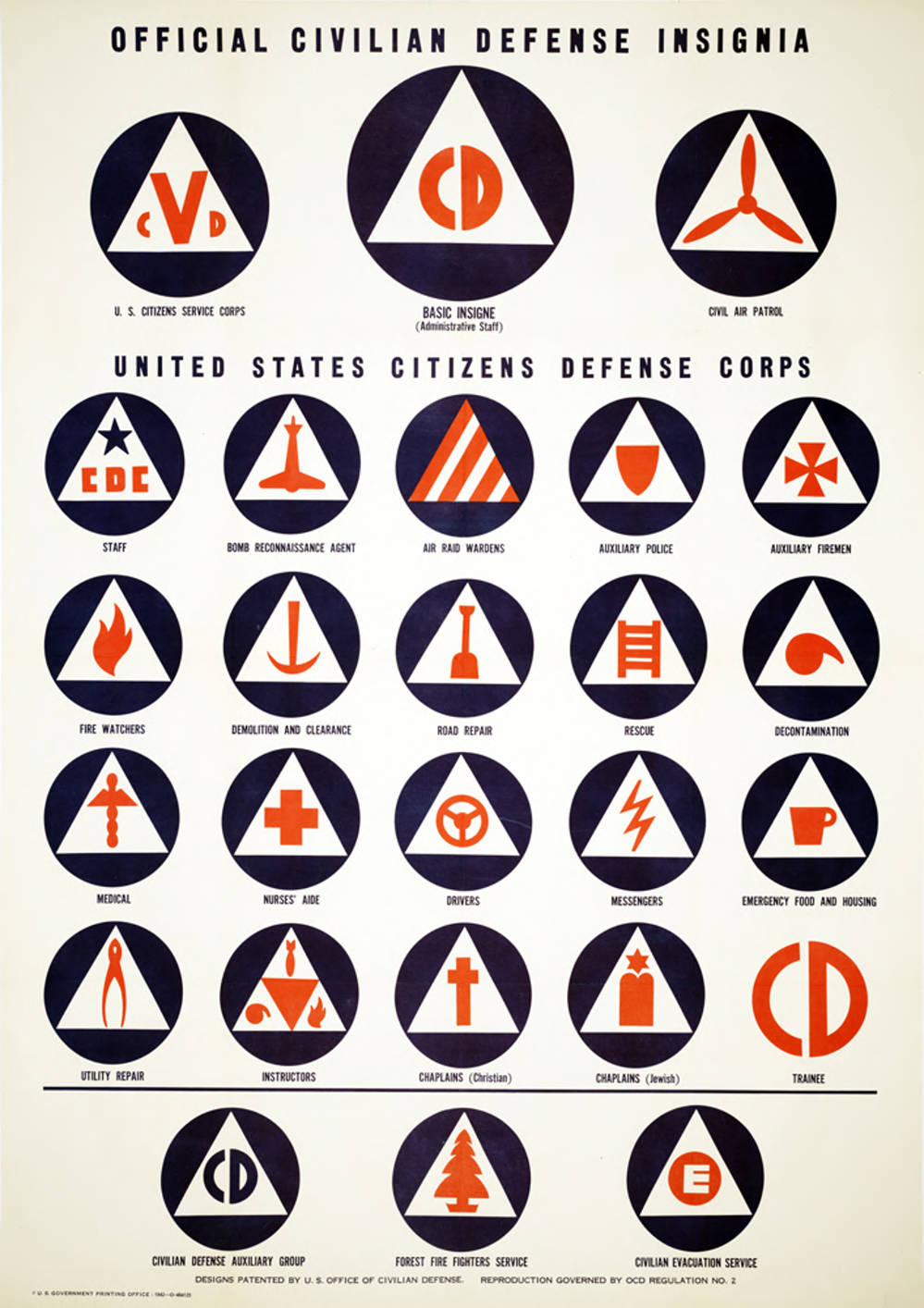

Civil Defense

Civil defense or civil protection is an effort to protect the citizens of a state (generally non-combatants) from military attacks and natural disasters. It uses the principles of emergency operations: prevention, mitigation, preparation, response, or emergency evacuation and recovery. Programs of this sort were initially discussed at least as early as the 1920s and were implemented in some countries during the 1930s as the threat of war and aerial bombardment grew. It became widespread after the threat of nuclear weapons was realized.

Since the end of the Cold War, the focus of civil defense has largely shifted from military attack to emergencies and disasters in general. The new concept is described by a number of terms, each of which has its own specific shade of meaning, such as crisis management, emergency management, emergency preparedness, contingency planning, civil contingency, civil aid, and civil protection.

In some countries, civil defense is seen as a key part of "total defense". For example, in Sweden, the Swedish word "totalitarian" refers to the commitment of a wide range of resources of the nation to its defense - including to civil protection. Respectively, some countries (notably the Soviet Union) may have or have had military-organized civil defense units (Civil Defense Troops) as part of their armed forces or as a paramilitary service.

Baltimore's Mayor's Office of Emergency Management

Mayor's Office of Emergency Management MOEM evolved from the City’s Civil Defense program, originally established to prepare for the nuclear dangers of the Cold War.

In 2002, under Mayor Martin O’Malley, the office was moved from the Department of Public Works into the Fire Department.

From 2005-2007, Fire Chief William J. Goodwin, Jr. also filled the role of emergency manager for the City.

In 2008, under Mayor Sheila Dixon, the Office of Emergency Management was incorporated into the Mayor’s Office for policy and citywide program coordination purposes. Administratively, the office remains part of the Fire Department.

Today, MOEM works on preparedness and response for a variety of hazards that can occur in Baltimore.

Coastal and flash flooding, severe storms, power outages, blizzards, hazardous materials incidents, bomb threats, and numerous other incidents that require a multi-agency or multi-jurisdictional response, have occurred in the City in the last five years. During these events, MOEM works to coordinate resources and make sure that the affected citizens receive all of the help that the City can access.

Baltimore City Police

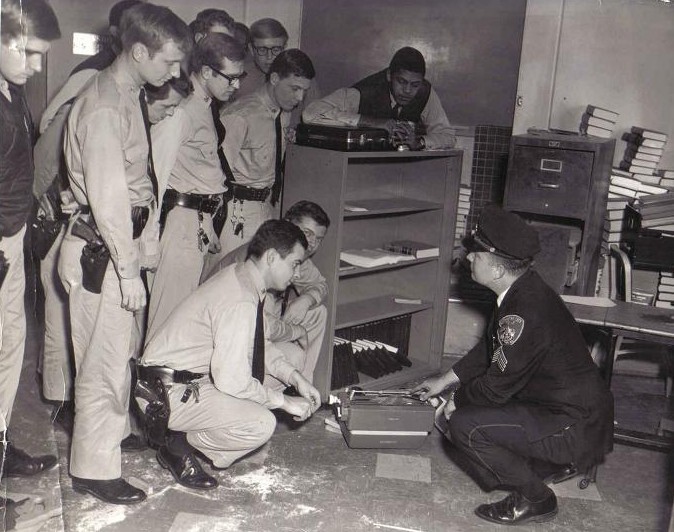

WW1 Era US ARMY M1917 Doughboy Helmet

Modified during the 2nd World War by a WD officer this M1917 doughboy helmet was painted black

with B.C.P. painted on front and WD painted inside for use during civil defense or civil protection details

(We don't know the complete back story to this. It would appear from markings on the inside that it may have been used in the WD)

The old U.S. civil defense logo was used in the FEMA logo until 2006 and is hinted at in the United States Civil Air Patrol logo. Created in 1939 by Charles Coiner of the N. W. Ayer Advertising Agency, it was used throughout World War II and the Cold War era. In 2006, the National Emergency Management Association — a U.S. organization made up of state emergency managers—"officially" retired the Civil Defense triangle logo, replacing it with a stylised EM (standing for Emergency management). The name and logo, however, continue to be used by Hawaii State Civil Defense and Guam Homeland Security/Office of Civil Defense

From the air raid warning and plane spotting activities of the Office of Civil Defense in the 1940s, to the Duck and Cover film strips and backyard shelters of the 1950s, to today’s all-hazards preparedness programs led by the Department of Homeland Security, Federal strategies to enhance the nation’s preparedness for disaster and attack have evolved over the course of the 20th century and into the 21st.

Presidential administrations can have a powerful impact on both national and citizen preparedness. By recommending funding levels, creating new policies, and implementing new programs; successive administrations have adapted preparedness efforts to align with changing domestic priorities and foreign policy goals. They have also instituted administrative reorganizations that reflected their preference for consolidated or dispersed civil defense and homeland security responsibilities within the Federal government.

Programs were seldom able to get ahead of world events, and were ultimately challenged in their ability to answer the public’s need for protection from threats due to bureaucratic turbulence created by frequent reorganization, shifting funding priorities, and varying levels of support by senior policymakers. This in turn has had an effect on the public’s perception of national preparedness. Public awareness and support have waxed and waned over the years, as the government’s emphasis on national preparedness has shifted.

An analysis of the history of civil defense and homeland security programs in the United States clearly indicates that to be considered successful, national preparedness programs must be long in their reach yet cost effective. They must also be appropriately tailored to the Nation’s diverse communities, be carefully planned, capable of quickly providing pertinent information to the populace about imminent threats, and able to convey risk without creating unnecessary alarm.

The following narrative identifies some of the key trends, drivers of change, and lessons learned in the history of U.S. national preparedness programs. A review of the history of these programs will assist the Federal government in its efforts to develop and implement effective homeland security policy and better understand previous national preparedness initiatives.

Pre-Cold War Period (1917-1945)

World War I introduced a new type of attack: the use of strategic aerial strikes against an enemy’s population to degrade its ability and will to wage war. German aerial bombardment of towns in countries such as France, Belgium, and Poland began in August 1914, and in the following year Kaiser Wilhelm authorized sustained bombing campaigns against military and civilian targets, particularly against England.1 From May through October of 1915, Germany launched seven air strikes against London alone.2 England, like most other nations at the time, did not have an organized civil defense program to aid citizens during such attacks. Individuals were forced to find their own way to safety, often taking refuge in the city’s underground subway stations.3 By all assessments, the damage and casualty figures that resulted from these early bombing operations were comparatively insignificant, but they exerted a psychological toll on the British public.4 It became clear that civilian defense, involving a range of actions to protect the general public in the event of attack, would become a major fixture in future warfare.

Though the Axis and Allied powers continued to employ strategic bombing throughout World War I, leaders in the United States did not feel that the country was vulnerable to attack. They concentrated their public outreach on rallying support for the war effort.5 Much of this task was coordinated by the Council of National Defense, established on August 29, 1916 with the passage of an Army appropriations bill.6 The Council was a presidential advisory board that included the Secretaries of War, Navy, Interior, Agriculture, Commerce, and Labor; assisted by an Advisory Committee appointed by the President.7 Its responsibilities included “coordinating resources and industries for national defense” and “stimulating civilian morale.”

The work of the Council escalated when the United States entered the war in 1917. In the same year, the Federal government asked State governors to create their own local councils of defense to support the National effort.9 However, the Council’s activities continued to focus more on facilitating mobilization for the war than on protecting civilian resources. When hostilities ended, the Council shifted its efforts toward demobilization. Its operations were suspended in June, 1921.

For the remainder of the 1920s, the Federal government undertook little public outreach related to defense and security. However, the 1930s saw a revival of civil defense efforts, when aggressive actions and arms stockpiling in Europe fueled international concern.11 In 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt created by executive order the National Emergency Council (NEC) which consisted of the President, his Cabinet members, and the head of nearly every major Federal agency, commission, and board.12 The mission of the NEC included a variety of programs unrelated to civil defense; however, its duties also included coordination of emergency programs among all agencies involved in national preparedness.

As World War II ignited in Europe, Roosevelt reestablished the Council of National Defense in 1940.14 Once again States were asked to establish local counterpart councils. Tensions among Federal, State and local governments began to rise about authority and resources.

The states claimed they were not given enough power to manage civil defense tasks in their own jurisdictions, and local governments asserted that State governments did not give urban areas proper consideration and resources.15 Non-attack disaster preparedness remained almost entirely the responsibility of States, while federal funding was reserved primarily for attack preparedness.

Because of extensive civilian bombing campaigns in Europe, concerns about possible attacks against the U.S. homeland increased. Mayor Fiorello La Guardia of New York City wrote a letter to President Roosevelt stating:

“There is a need for a strong Federal Department to coordinate activities, and not only to coordinate but to initiate and get things going. Please bear in mind that up to this war and never in our history, has the civilian population been exposed to attack. The new technique of war has created the necessity for developing new techniques of civilian defense”

President Roosevelt responded to the increasing concern of the public and local officials by creating the Office of Civilian Defense (OCD) in 1941.17 The President delegated a number of responsibilities to the OCD by broadly interpreting civilian protection to include morale maintenance, promotion of volunteer involvement, and nutrition and physical education.18 The OCD oversaw unprecedented federal involvement in attack preparedness. As with the Council of National Defense, the OCD created corresponding defense councils at the local level.

The issue of whether the OCD should emphasize protective services, typically done at that time by men, or social welfare services, typically undertaken at that time by women, created tension from the office’s inception.20 Director Fiorello LaGuardia referred to “non protective” activities as “sissy stuff” and saw opportunities to build neighborhood militias. Pressured to focus on other non protected areas such as neighborhood support, he appointed Eleanor Roosevelt to expand volunteer activities.21 The two leaders, with their radically divergent points of view, exemplified a conflict over the meaning and purpose of civil defense that would continue well into the cold war era.

OCD received criticism from Congress and the public on several fronts. It was called “pink” by influential politicians who disliked the program’s broad reach and social development programs. Some believed the organization’s tasks were better undertaken by the Department of War.22 One of OCD’s early leaders, James Landis, recommended that the organization be abolished, since the threat of an attack on U.S. civilians had receded.2

With the end of World War II, most U.S. officials agreed that the risk of an attack on the U.S. homeland was minimal. Roosevelt did not take Landis’ suggestion, and the OCD continued to operate.24 While the OCD did not fulfill all of its ambitious goals, it did begin the development of concrete civil defense plans, including air raid drills, black outs, and sand bag stockpiling

Truman Administration (1945-1953)

Soon after taking office, Harry Truman did follow Landis’ advice and abolished the OCD, reflecting the widely held belief that the immediate threat of war had receded. 26 Initially, civil defense was not a high priority in the Truman Administration, as troops began to return home and other war time offices were diminished in scale or disbanded altogether. The development of the atomic bomb, however, had opened up previously unthinkable risks. Increasing hostilities with the Soviet Union and their pursuit of a nuclear bomb threatened the United States.

In this context, Truman began to reexamine the national defense structure, reviewing the results of a set of commissions.27 In 1946, the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey published its report evaluating the results of strategic bombing campaigns by imperial Germany and Japan against enemy civilian populations. The report indicated that civil defense plans could significantly mitigate the effects of strategic bombing.28 Specifically, mass evacuation plans for urban areas and shelters for those unable to leave the area could form components of a viable civil defense plan.29 In 1947, the War Department’s Civil Defense Board, led by Major General Harold Bull, released a second report.30 The so-called Bull Report stated that civil defense is the responsibility of civilians, and the military should not be expected to get involved in such matters.31 According to the report, civil defense was best implemented locally, a concept referred to as “self-help”. Still, the document did concede that the Federal government could provide the majority of necessary resources.32 Additionally, Congress passed the National Security Act of 1947. Best known for the creation of the Central Intelligence Agency, the Act also created the National Security Resources Board (NSRB), which was initially responsible for mobilizing civilian and military support, as well as maintaining adequate reserves and effective resource use in the event of war.

Neither report resulted in substantial reforms to the Truman Administration’s policies because civil defense continued to remain a low priority. 34 However, as U.S.-Soviet relations became increasingly strained, President Truman began to implement civil defense policy reforms. These changes resulted, in part, from the strong recommendation of Colonel Burnet Beers, who was responsible for directing a study on future civil defense planning and operations to establish a civil defense unit in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD).35 Truman acted promptly on this advice, establishing the Office of Civil Defense Planning (OCDP), whose purpose was to recommend a course for the creation of a permanent civil defense agency. 36 After six months, the OCDP released its 300-page Hopley Report, 37 which called for the creation of a Federal office of civil defense directly under the President or Secretary of Defense. The report additionally recommended that the Federal government provide civil defense guidance and assistance, but that State and local governments handle most of the operational responsibilities.

Reactions to the Hopley Report inside and outside government were generally negative. There were concerns about the cost and scope of civil defense. Many people feared its recommendations were too far-reaching and made unrealistic demands on the public and government.39 And there were concerns about military control. Some civilian groups thought the report called for transferring what should be a civilian responsibility to the military, which could lead to a “garrison state.”

Truman ultimately chose to address the latter concern by assigning civil defense planning to the NSRB, a civilian agency.41 However, the NSRB did not receive the necessary resources or authority to carry out its mandate.42 As a result, the Board was moved to the Department of Defense (DOD), then shifted to the Executive Office of the President, and finally had its responsibilities transferred to the Office of Defense Mobilization in December of 1950.

The climate of civil defense changed dramatically with the successful Soviet test of a nuclear weapon in August of 1949. The United States lost its monopoly on nuclear weapons and the corresponding negotiating power that this entailed. Local officials began to demand from the Federal government a clear outline of what they were to do in crisis situations.43 The Truman Administration received criticism from local officials, a worried American public, and Congress for not taking firm action.44 In response, in 1950, the NSRB generated a new proposal called the Blue Book, which outlined a set of civil defense functions and how they should be implemented at each level of government.45 The Blue Book also recommended the creation of an independent Federal civil defense organization.

Truman agreed with many of the Blue Book recommendations, but held firm to his belief that civil defense responsibilities should fall mostly on the shoulders of the State and local governments.47 In response, Congress enacted the Federal Civil Defense Act of 1950, which placed most of the civil defense burden on the States and created the Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) to formulate national policy to guide the States’ efforts.

As planning began, policymakers struggled to define what was meant by national security. A key question was the appropriate level of readiness to be attained. At what readiness level would people have to surrender personal freedoms to state control? At what level of security would civil defense metamorphose into a garrison state, undermining the underlying purpose of protecting individual rights?49 The decision to assign civil defense responsibility to States and localities was intended partly as a safeguard against the garrison state.

Planners also struggled with a difficult political question: just how much support should government provide? Congressional resistance to paying for a comprehensive program, and concerns about establishing public dependency on government, led to adoption of a doctrine of “self help”: individual responsibility for preparedness to minimize (not eliminate) risk.50 The idea of decentralized, locally controlled, volunteer based civil defense was not new; in fact it was the foundation of the successful British civil defense effort in World War II. However, the decision to make self-help the basis of civil defense was also a political compromise, a way to balance conflicting views over the size, power, and priorities of the emerging postwar nation.

The FCDA led shelter building programs, sought to improve Federal and State coordination, established an attack warning system, stockpiled supplies, and started a well known national civic education campaign. In 1952, the FCDA joined with the Ad Council to release Korean War advertising to boost national morale.52 The FCDA specifically aimed to teach schoolchildren about preparedness, primarily through civil defense drills.53 In order to effectively educate the entire youth population, the FCDA commissioned a movie studio to produce nine civil defense movies that would be shown in classrooms across the nation – among them Duck and Cover.54 The movie, through its main character Bert the Turtle, showed children what to do when they saw “the flash of an atomic bomb.”55 Newspapers and experts generally heralded the film as a positive and optimistic step toward preparedness.56 The New York Herald Tribune, for example, called the film “very instructive” and “not too frightening for children.”57 Ultimately, the film was seen by millions of schoolchildren during the 1950s.58 The public education campaign throughout the decade promoted the idea that with preparation, a nuclear attack could be survivable

An examination of the FCDA-led shelter building initiative underscores some of the civil defense program’s internal inconsistencies. The Federal Civil Defense Act of 1950 allocated significant funding to a shelter initiative. The law allowed the FCDA to develop shelter designs and make financial contributions to shelter programs. However, Congress stipulated that the Federal government could not finance the construction of new shelters.60 In communities across the country there was great debate over the necessity of the shelters, and Truman himself was not eager to spend government money on the program.61 Moreover, FCDA Administrator Millard Caldwell initiated a public relations fiasco when he misconstrued the shelter program as a means to protect every person in the country. A program that expansive was deemed to be too costly to receive sufficient political support; as a result, it never left the planning stages during the Truman Administration. Contrary to the outlook offered by Duck and Cover and the other educational campaigns, early media reports about the possibility of nuclear war offered grim predictions concerning the aftermath of an attack. The scenarios were horrific, and the association of civil defense with death and destruction made not only home preparedness and sheltering, but the whole self-help preparedness concept, a tough sell.

The political, fiscal, and emotional crosscurrents were reflected in civil defense funding. Despite ambitious funding requests, actual appropriations to civil defense remained low throughout the Truman Administration, and throughout the 1950s. For example, from 1951 to 1953 Truman requested $1.5 billion for civil defense, but appropriations totaled only $153 million – 90 percent less than requested 6

Despite these practical setbacks, the concept of civil defense as a purposeful approach to the protection of citizens from threats outside the Nation’s borders began to take shape during Truman’s presidency.65 Though each leader who followed would focus on different programs and approaches, civil defense remained an important initiative during the coming decades

Eisenhower Administration (1953- 1961)

President Dwight Eisenhower’s approach to civil defense was quite different from his predecessor’s. Eisenhower identified the enormous economic commitment required for military development as one reason not to undertake expensive civil defense programs.66 Additionally, Republicans in Congress were eager to curtail spending, as the party had publicly promised to balance the budget when Eisenhower took office.67 Though Eisenhower requested less funding than Truman, actual appropriations were virtually identical to appropriations under Truman

In addition to economic concerns, world events contributed to Eisenhower’s decision to support a mass evacuation policy, instead of the shelter program initiated under Truman. In 1953, the Soviets detonated a hydrogen nuclear bomb; and shortly thereafter, the effects of the initial U.S. hydrogen explosion were released to the American public.69 The blast and thermal effects of these new fusion nuclear weapons were so destructive that many experts argued that American cities would be doomed in the event of a nuclear attack, regardless of sheltering efforts.70 As a result, new FCDA Administrator Frederick Peterson urged Congress to scale back or completely eliminate the shelter program

In strongly supporting mass evacuation, Peterson noted that successful execution would depend on sufficient warning time, proper training for civil defense officials, and regular public drills.72 Many of the responsibilities for evacuation would be borne at the State and local level, which appealed to Eisenhower’s belief that the Federal government should not shoulder the entire burden for civil defense programs.73 Congress also was in favor of the shift in attention from shelters to evacuation.74 Yet some members, especially Congressman Chet Holifield of California, were adamantly opposed to reducing the shelter system.75 Holifield was the ranking member of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy and later the chairman of the Military Operations Subcommittee.76 In support of a federally funded shelter system, he likened the idea of family built shelters to creating “an army or a navy or an air force by advising each one to buy himself a jet plane.”77 As a well publicized champion for shelter building, Congressman Holifield consistently and persuasively articulated the benefits of shelter building to the American public.

In March of 1954, the United States detonated another thermonuclear bomb, called Bravo, on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands.78 Due to a major wind shift, a large amount of radioactive fallout was unexpectedly released over a 7000 square mile area, ultimately poisoning the crew of a Japanese fishing boat in the area and even injuring personnel involved in the test.79 It did not take long for Congress and the public to turn their attention to the need for shelters to protect the citizenry from such lethal effects.80 The FCDA was in a tough position. They had just fought for evacuation policies, at the expense of the shelter option, and the Eisenhower Administration continued to support evacuation as the chief civil defense objective.81 Faced with this dilemma, FCDA Administrator Peterson redirected his policy toward an “evacuation to shelter” approach, whereby individuals would be evacuated from affected areas to shelters.82 He even proposed digging ditches along roadsides for those who could not get to shelters in time.

The Eisenhower Administration had just begun work on its massive federal highway program, connecting major cities and in the process providing a means for evacuation.84 Peterson clashed with the President on the program, arguing that Congress should divert some of the highway funding to support civil defense programs. He believed that the highways should be designed to lead only 30 to 40 miles outside of major cities to rural “reception areas.”85 However, Peterson’s clout did not match the President’s, and thus no money was diverted from the highway program The FCDA received extensive criticism over the next few years for not developing a feasible plan for evacuating major cities.87 Congressman Holifield called FCDA efforts only a façade of civil defense programs.88 He also chastised the President for not taking more responsibility.89 At Holifield’s request, in 1956 the House Committee on Government Operations held a series of hearings to discuss the viability of the FCDA.90 The “Holifield Hearings” constituted the largest examination of the civil defense program in U.S. history

Holifield and his Committee concluded that the FCDA had been myopically focused on evacuation, which they termed “a cheap substitute for atomic shelter.”92 The FCDA responded by presenting a National Shelter Policy, which proposed a $32 billion program for “federally subsidized self-help” (e.g. tax incentives or special mortgage rates to shelter owning families).93 Taken aback by the cost of the proposal, Eisenhower convened the Gaither Committee (named for its first chairman, H. Rowan Gaither) composed of leading scientific, military, and business experts. The committee evaluated military readiness and concluded that the United States could not defend itself from a Soviet surprise attack on the homeland. 94 While its report, released in 1957, emphasized funding anti-ballistic missile (ABM) defense systems, it also acknowledged that a fallout shelter system occupied a secondary position in deterrence, and to that end recommended adopting the FCDA shelter proposal.95 Two subsequent reports advanced similar ideas.96 In 1958, the Rockefeller Report, compiled by a board of experts and practitioners directed by Henry Kissinger, stated that civil defense was one aspect of a robust deterrent that should also include more investment in offensive military capabilities.97 That same year, a report published by the RAND Corporation emphasized the importance of civil defense as a powerful component of deterrence.

Despite these supporting reports, the FCDA shelter proposal continued to run counter to the views of top officials in the Eisenhower Administration. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles argued that the nation should focus resources on retaliation capabilities and curtail the shelter program.99 Military leaders also opposed the shelter program, fearing it would cut into defense spending.100 Eisenhower himself remained opposed to the massive shelter program.101 Instead of pursuing the National Shelter Policy, he instructed the FCDA to initiate much more limited actions, including research on fallout shelters, a survey of existing structures, and informing the public about shelters.

Holifield and other legislators were outraged that the President would disregard the findings of three separate committees.103 Supporters of the shelter system publicly expressed disappointment with the Eisenhower administration, and Holifield commented that civil defense was in a “deplorable” state during this period.104 Finally, in the face of strong criticism, Eisenhower largely dissolved the FCDA to make way for the short-lived Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization (OCDM), which began the bulk of its work during the Kennedy presidency

It bears noting that for all of his public opposition to massive sheltering programs, in the middle of his tenure Eisenhower secretly commissioned the building of an underground bunker in West Virginia that would serve as a safe haven for top members of Congress, in the event of a catastrophe.106 The project was similar in scope and intent to one initiated by President Truman in 1951. Called “Site R,” that effort involved construction of an Alternate Joint Communications Center in Raven Rock Mountain, Pennsylvania, to be used in case existing centers in Washington, DC were destroyed by an attack.107 Like his predecessor, Eisenhower believed it was vital for the government to ensure continuity of operations following an attack on the homeland. The West Virginia bunker was built under the five-star Greenbrier resort and was only placed on full alert once, during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962.108 The public remained completely unaware of the operation until 1992 when the Washington Post broke the story.

Kennedy Administration (1961-1963) During the first year of his presidency, John F. Kennedy made civil defense more of a priority than at any previous time in U.S. history.110 He was also the first President to discuss civil defense publicly, issuing an appeal in the September 7, 1961 issue of LIFE magazine to all Americans to protect themselves “and in doing so strengthen [the] nation.”111 Kennedy continued the approach of his predecessors of including civil defense in deterrence calculations, and he believed that the only effective deterrent was a strong retaliatory capability. 112 However, he also believed that deterrence could fail in the event one faced an irrational enemy, and thus a strong and coordinated approach to civil defense was required. As he stated to Congress on May 25, 1961

[Civil defense] can be readily justifiable…as insurance for the civilian population in case of an enemy miscalculation. It is insurance we trust will never be needed – but insurance which we could never forgive ourselves for foregoing in the event of catastrophe.

He concluded by proposing “a nationwide long-range program of identifying present fallout shelter capacity and providing shelter in new and existing structures.”

To accomplish these goals, Kennedy issued Executive Order 10952 on July 20, 1961, which divided the Office of Civil Defense and Mobilization into two new organizations: the Office of Emergency Planning (OEP) and the Office of Civil Defense. OEP was part of the President’s Executive Office and tasked with advising and assisting the President in determining policy for all nonmilitary emergency preparedness, including civil defense. OCD was part of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, and was tasked with overseeing the nation’s civil defense program. The responsibility for carrying out the fallout shelter program was among the program operations assigned to Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.

The 1961 Berlin crisis gave Kennedy renewed urgency to improve US civil defense. The President emphasized the importance of fallout shelters as a means to save lives.

He stressed that identifying and stocking existing shelters with food and medicine should be made a priority.117 McNamara explained that this approach was not a major departure from the Eisenhower shelter program; however, the scope was larger and thus required more money.118 The goal was to provide maximum protection through cost effective means by utilizing existing buildings. Some members of Congress, notably the ranking Republican of the House Appropriations Committee, John Taber, worked hard to limit funding to the shelter project. However, most underscored the importance of the shelter program as a rational response to the growing threat of a nuclear attack.119 Congress ultimately approved more than $200 million that Kennedy asked for the project, which was twice as much as Eisenhower had ever requested for civil defense.

With the appropriated funds, OCD began a nationwide survey of all existing shelters.121 In order to be designated a public shelter, a facility had to have enough space for at least 50 people, include one cubic foot of storage space per person, and have a radiation protection factor of at least 100.122 The materials division of DOD, called the Defense Supply Agency, furnished shelter supplies to local governments, which were then responsible for stocking all shelters in their regions.123 By 1963, 104 million individual shelter spaces had been identified;124 and of those 47 million had been licensed, 46 million marked, and 9 million individual spaces had been stocked with supplies.

The President also decided to distribute booklets to the populace that would outline the purpose of the shelter program and the steps that every American should take during an attack. The booklet, created by a team of Madison Avenue writers, was to be sent to every household in the nation.126 In an unintended twist, the booklets themselves created new controversy. Some presidential aides felt that the pictures used were too graphic, while others felt that they indicated the booklet was meant only for the upper class.127 Ultimately the Kennedy Administration decided to tone down the content, so as not to cause unnecessary alarm.128 The booklets were then sent to post offices throughout the nation, so people could pick up copies.

The means of communicating the Administration’s civil defense message to the public was not the only target of controversy during this time. Reviving a long-standing debate, some prominent members of Congress, including Albert Thomas, the Chairman of the House Appropriations Subcommittee in charge of civil defense, felt that the Federal government should not be undertaking such a massive sheltering project when civil defense responsibility belonged to State and local governments.129 Kennedy convened a meeting with eighteen of his top advisors at Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, on the day after Thanksgiving in 1961 to discuss the appropriate next steps for civil defense.130 There, consensus evolved that the Federal government’s primary role was to provide community shelters.

Johnson Administration (1963-1969) Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963 marked the beginning of a drastic cutback in funding of the Nation’s civil defense program. The topic began to fall slowly off the public radar, and President Lyndon B. Johnson allowed it to slip further by not pressuring Congress to pass the Shelter Incentive Program bill,132 which proposed to give every non-profit institution financial compensation for each shelter it built.

Earlier in the decade, Secretary McNamara had begun to describe the concept of “mutual assured destruction” (MAD), which essentially meant that the Soviet Union and the United States had the capacity to effectively annihilate one another with the weapons in their arsenals, such that this constituted an effective deterrent to offensive action.134 Congress and the public began to accept the doctrine of MAD. As a result, a growing percentage of the population began to wonder if civil defense programs could adequately protect citizens from a large scale nuclear attack.135 However, when the U.S. military began expanding its ABM defense system, McNamara re-emphasized the importance of a shelter system because he questioned the wisdom of relying solely on an ABM defense.136 He argued that “the effectiveness of an ABM defense system in saving lives depends in large part upon the availability of adequate fallout shelters for the population.”137 The belief was that the ABM defense system could be beaten by detonating nuclear weapons upwind of large metropolitan areas and outside the range of the defensive missiles. The result would be radioactive fallout spreading across America’s cities.138 Large numbers of people would die from the exposure to the fallout, unless there were a sufficient number of shelters. Congress opposed financing a shelter system, and McNamara continued to be pessimistic about an ABM defense system saying, “Whether we will ever be able to advance the art of defense as rapidly as the art of offensive developments…I don’t know. At the moment it doesn’t look at all likely.”

In an ironic twist, attention to civil defense was also undermined by a series of major natural disasters that rattled the Nation. Hurricanes Hilda and Betsy devastated the Southeast, an Alaskan earthquake caused a damaging tidal wave in California, and a lethal tornado swept through Indiana on Palm Sunday in 1965.140 Senator Birch Bayh of Indiana sponsored legislation that granted emergency Federal loan assistance to disaster victims.141 The bill passed in 1966, and Bayh urged Congress over the next few years to provide even more disaster assistance to citizens. The concept of all-hazards assistance was gaining adherents, at the expense of civil preparedness for attack.

The Vietnam War struck a further blow to civil defense during the Johnson years. As the war progressed, it required increasing amounts of time, money, and resources.143 Although civil defense efforts continued to receive modest funding, and would for the next twelve years, no major steps were taken to enhance overall capabilities.144 A transformation in the way the Federal government viewed the task of protecting the public had begun.

Nixon Administration (1969-1974)

By the time President Nixon entered office, public and government interest in civil defense had fallen precipitously from its peak in the early 1960s. According to the New York Times Index, in 1968, only four articles on civil defense appeared in that publication compared to 72 in 1963.145 However, the new administration did make a major contribution to civil defense by redefining civil defense policy to include preparedness for natural disasters. In no small measure, the President’s thinking resulted from the Federal government’s lack of preparedness to handle the horrific damage wrought by Hurricane Camille (see discussion below). Upon entering office, Nixon immediately tasked the OEP to complete a broad review of the Nation’s civil defense programs.

In June 1970, the OEP released the results of its comprehensive assessment in National Security Study Memorandum 57. 147 The study concluded that the Nation’s preparedness for natural disasters was minimal to nonexistent.148 The Administration responded by introducing two of its most significant domestic policy changes in National Security Decision Memorandum (NSDM) 184. NSDM 184 recommended the establishment of a “dual-use approach” to Federal citizen preparedness programs and the replacement of the Office of Civil Defense with the Defense Civil Preparedness Agency (DCPA).149 President Nixon would later implement these recommendations, placing the new DCPA under the umbrella of the Department of Defense.

For the first time in the history of civil defense, Federal funds previously allocated for the exclusive purpose of preparing for military attacks could be shared with State and local governments for natural disaster preparedness. This dual-use initiative subscribed to the philosophy that preparations for evacuation, communications, and survival are common to both natural disasters and enemy military strikes on the homeland. From a practical perspective, the dual-use approach allowed more efficient utilization of limited resources, so planners could address a larger number of scenarios. 150 Given that civil defense funding during Nixon’s first term barely exceeded the low $80 million per year level of the Eisenhower Administration (when adjusted for inflation), scarce resources likely played a part in the decision to adopt the new approach.

A series of natural disasters during Nixon’s tenure also increased the pressure to expand civil defense to include preparation and response to natural disasters. Several major hurricanes and earthquakes exposed significant flaws in natural disaster preparedness at a time when no centralized system for disaster relief existed.152 Perhaps most significantly, in August 1969 Hurricane Camille wreaked havoc in the greater Gulf Coast region, highlighting major problems with disaster response.153 In response, Congress passed the Disaster Relief Act of 1969, which created the concept of a Federal Coordinating Officer (FCO). The FCO was an individual appointed by the President, who would manage federal disaster assistance onthe-spot at a given disaster area The President’s decision to increase focus on natural disaster preparedness also aligned with U.S. foreign policy considerations. In order to reinforce the doctrine of MAD, Nixon was deeply involved in negotiations with the Soviet Union to limit defensive weapon capabilities. 155 The first Strategic Arms Limitation Talks treaty (SALT I), signed on May 26, 1972, froze the number of strategic ballistic missile launchers and allowed the addition of new submarine ballistic missile launchers only as replacements for dismantled older launchers. 156 Perhaps most significantly, SALT I limited the superpowers to only two ABM defense deployment sites. 157 Advocates of SALT argued that such agreements were necessary because any increase in defense capabilities would spur another arms race for improved offensive capabilities. 158 The Nixon Administration felt that the SALT I advances would be jeopardized if either side continued to build up nuclear attack-related civil defense programs. This concern helped justify the decision to turn more attention toward civil preparedness for natural disasters.

The dual use approach was attractive to State and local authorities. While in the past State and local officials had been reluctant to participate in nuclear attack planning, the ability to deal with attack preparedness in the context of a particular hazard in a specific area (e.g. floods in coastal or riverine areas, hurricanes in coastal areas, tornadoes in the Midwest and Plains States, and civil unrest in urban areas) encouraged new coordination and participation

The change of focus also garnered public support. The interest of the American public in attack planning had waned considerably. There was little enthusiasm for ambitious shelter building projects or evacuation drills.161 A number of historians attribute this lack of interest to a diminished perception of risk, psychological numbing to the destruction of nuclear weapons, and a growing belief that civil defense measures would not ultimately be effective in the event of nuclear war.162 Planning for natural disasters was perceived to be more effective, less resource intensive, and able to deliver tangible benefits at the State and local level.

Nixon’s broad policy changes were accompanied by equally sweeping organizational changes. Following the replacement of the OCD with the DCPA, another major reorganization took place. In 1970 and 1973, Reorganization Plans 1 and 2 abolished the Office of Emergency Planning and delegated its functions to various agencies.163 Executive Order 11725 of 1973 solidified the new organizational structure by distributing preparedness tasks to a wide variety of new agencies including the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the General Services Administration, and the Departments of the Treasury and Commerce.164 In total, the new bureaucratic structure placed responsibility for disaster relief with more than 100 federal agencies.165 Not surprisingly, this reorganization is perhaps best known for its ineffectiveness.

Despite the suggestion of great activity, real progress on civil defense, both in the traditional sense and its new dual-use direction, was limited during the Nixon Administration. One illustrative example is the signing into law of the Disaster Relief Act of 1974 (Public Law 93-288). While the Disaster Relief Act sought to remedy bureaucratic inefficiencies and provide direct assistance to individuals and families following a disaster,167 funding remained low, with levels comparable to spending in the pre Kennedy years. The Act did succeed in involving State and local governments in all hazards preparedness activities 168 and provided matching funds for their programs.169 However, soon the federal government’s emphasis on all-hazards preparedness would lessen.

Ford Administration (1974-1977)

At first, the Ford Administration supported its predecessor’s approach to dual-use preparedness. In March 1975 President Ford strongly endorsed the policy, stating: “I am particularly pleased that civil defense planning today emphasizes the dual use of resources…we are improving our ability to respond…to national disasters…”170 However, less than a year later, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) rescinded DOD’s use of civil defense funding for natural disaster mitigation and preparedness.171 Civil defense was returned to the original orientation of nuclear attack preparedness, as seen during the Truman and Eisenhower years.

There were several motivations for this policy change. Perhaps most importantly, the United States had just resumed its intelligence observations of Soviet civil defense after a five year break.172 Reports from these operations detailed significant Soviet progress in civil defense, compared to relatively small U.S. efforts. Massive Soviet expenditures (estimated at $1 billion per year in 1977) on preparedness initiatives, such as evacuation plans, contributed to a growing concern that the United States was falling behind.173 Whereas in the United States, civil defense was considered “an insurance policy,” the Soviets considered it a “factor of great strategic significance.”174 The most alarmist American commentators concluded that the entire U.S. nuclear arsenal could not inflict significant damage on the Soviet Union, due in large part to its increased civil preparedness.

Developments in Cold War diplomacy likely also contributed to the temporary end of all hazards planning. Gradually the doctrine of MAD was replaced with new ideas, such as limited nuclear strikes against strategically important military and industrial targets,

rather than population centers. As early as January 10, 1974 Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger stated during a press conference that “the old policy [of MAD]…was no longer adequate for deterrence” and should be replaced by “a set of selective options against different sets of targets.”176 Over the next decade, these ideas of flexible targeting and limited retaliation developed into the policy of “flexible response.”177 Flexible response was based on the idea that both the Soviet Union and the United States had the capability for small-scale nuclear attacks that could be answered by similarly-sized acts of retaliation by the other side.178 Theoretically, instead of massive retaliation against population centers, targets would be specific, highly-strategic sites.179 Since some of these sites could be civilian in nature, some level of civil defense and nuclear attack preparedness was deemed necessary. Thus, U.S. policy makers renewed their attention on civil defense, as a means of protecting against targeted highly-strategic attacks.

One result was a new initiative called the Crisis Relocation Plan (CRP). Begun in 1974 by Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger, the CRP favored a strategy of evacuation rather than sheltering. Directed by the DCPA, CRP evacuation planning was conducted at the State level with Federal funds and encompassed all of the necessary support for relocation, food distribution, and medical care.181 Under the CRP, urban residents would be relocated to rural host counties, with a target ratio of “5 immigrants for every native.”182 The focus on preparedness through the CRP was continued throughout the Ford Administration by incoming Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, who strongly opposed the dual-use approach. Rumsfeld believed that the Federal government should address only attack preparedness, while peacetime disasters were a State and local responsibility.

Though Administration officials and policymakers defended the CRP as a set of simple and highly effective procedures, the program suffered widespread criticism.184 The Plan’s reliance on a relatively long warning time (1 to 2 days), compared to the shorter notice necessary for sheltering, meant it could only be effective in a situation of rising tensions in which the launch of missiles against the country could be predicted. Additionally, vocal critics from Congress and the public doubted the feasibility of such large-scale evacuations through bottlenecked transportation routes.

Organizationally, the fragmentation of civil defense responsibilities begun under Nixon became increasingly apparent. Nixon’s reorganization plans prescribed that the bulk of the responsibility for civil defense fall to three different agencies: the OEP would advise the President, HUD’s Federal Disaster Assistance Agency would manage disaster relief, and the DCPA would coordinate State and local preparedness efforts.185 Though these bureaucratic changes were not complete until the Carter Administration, some Congressional committees were already beginning to investigate the problem of disjointed civil defense. In 1976, the House Armed Services Committee recommended that an office within the Executive Office of the President (EOP) be tasked to manage civil defense, while the Joint Committee on Defense Production recommended combining the three agencies into one body.186 These recommendations, coming during the final months of the Ford Administration, were evaluated in the subsequent Carter Administration.

Overall civil defense funding during Ford’s tenure did not change significantly from the Nixon years. With the implementation of the CRP, Secretary of Defense Schlesinger made modest increases in the 1975 budget to develop city evacuation plans and implement population defenses.187 However, as in previous Administrations, civil defense still competed for funding against more traditional military expenditures, and the 1975 increases were nullified the following year in favor of spending on offensive military capabilities

In sum, despite ambitious claims of progress by the Ford Administration, civil defense programs within the United States remained less than effective. U.S. nuclear deterrence plans still emphasized offensive capabilities. In its evaluation of the state of civil defense in 1976, the Congressional Research Service unconditionally labeled the efforts “a charade.”189 It would be another five years before significant progress was made

Carter Administration (1977-1981)

Upon taking office, President Carter immediately began a review of the disjointed system of bureaucracies that managed civil defense. An interagency study led to Presidential Review Memorandum 32 in September of 1977.190 The study concurred with the 1976 recommendations of the House Armed Services Committee and Joint Committee on Defense Production that the various civil defense agencies must be combined into one coherent agency in direct contact with the White House.191 In response, Carter issued Presidential Directive (PD) 41 in September of 1978, which sought to clarify the Administration’s view of civil defense. However, it did not offer any particular plan for implementation.192 According to PD 41, civil defense was an element in the strategy to “enhance deterrence and stability”. Civil defense still did not become a priority for the Administration, which concluded that it was not necessary to pursue “equivalent survivability” with the Soviet Union.

Meanwhile, in the midst of a lengthy debate regarding the creation of a single disaster preparedness agency, an unprecedented civilian nuclear accident unfolded on March 28, 1979 at the nuclear energy plant on Three Mile Island, near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.194 By highlighting the slow response, poor local Federal coordination, and miscommunications that occurred; the accident dramatically demonstrated the need for more effective disaster coordination and planning.195 Partially in response to the near nuclear disaster, on July 20, 1979 the Administration issued Executive Order 12148, which established the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) as the lead agency for coordinating Federal disaster relief efforts. FEMA absorbed the Federal Insurance Administration, the National Fire Prevention and Control Administration, the National Weather Service Community Preparedness Program, the Federal Preparedness Agency of the General Services Administration, and the Federal Disaster Assistance Administration activities from HUD, and combined them into a single independent agency. At the time, the creation of FEMA represented the single largest consolidation of civil defense efforts in U.S. history.

Despite the reorganization and move toward greater mission clarity, civil defense planning on the ground did not change dramatically. Practical plans continued to reflect traditional civil defense programs and did not adopt the dual-use approach, though Carter did urge FEMA to direct more of its efforts to coping with peacetime disasters.196 Evacuation continued to be the focus of Federal planners, and Secretary of Defense Harold Brown reaffirmed his predecessor’s crisis relocation strategies.197 When FEMA assumed responsibility for citizen preparedness, the agency called on civil defense planners nationwide to create area-specific CRPs.

The decision to continue to pursue evacuation as the primary civil defense policy was influenced by several factors. Well-funded and extensive Soviet evacuation programs continued to worry key U.S. decision makers, including Brown.199 Evacuation also made sense in the context of continued resource limitations. According to a 1979 FEMA report, since effective and cost-efficient sheltering in large cities had proven difficult, “the U.S. nuclear civil defense program developed into an evacuation program…as a low-cost survival alternative.”

It is likely that the Carter Administration’s focus on evacuation was also affected by Cold War diplomacy. The continuing SALT negotiations created a conflict between the desire to advance U.S. civil defense, and the desire to avoid upsetting the delicate strategic balance required for successful threat reduction negotiations. With this balance in mind, maintaining the status quo by continuing to support evacuation policies may have been deemed the best option.

Though the creation of FEMA and the goals of PD 41 signaled renewed interest in civil defense, funding throughout the Carter Administration remained historically low. The 1980 request for $108 million was less than adequate for implementing the new plans.202 In the following year, Congress did not meet a higher request for funding, instead choosing to allocate funds to other priorities.203 As had been the case many times before, funding levels did not match the ambitious plans for program improvement.

In keeping civil defense funding low, Congressional leaders had little public opposition to fear. In contrast to generally widespread public participation and acceptance in the peak years of civil defense during the early stages of the Cold War, most people by this time had little faith that any government civil defense planning could lessen the impact of nuclear war.204 Some local communities refused outright to cooperate with Federal civil defense mandates because they did not believe the CRPs would be effective if a nuclear attack were to occur.205 This public attitude would continue throughout the remainder of the Cold War period.

Reagan Administration (1981-1989) It would appear that Ronald Reagan entered office with the intention of building upon the civil defense foundations set by his predecessors. In December 1981, Congress acted dramatically in favor of the dual-use approach by amending the 1950 Civil Defense Act. In this milestone decision, all future civil defense funds would be allotted for natural disasters, as well as attacks on the homeland.206 The amendment did stipulate that funding and planning for peacetime disasters could not overtly detract from attack preparedness programs. Nevertheless, dual use preparedness was promoted with much of the same language and reasoning as it was during the Nixon Administration.

Though Reagan was in favor of the dual-use approach, his civil defense strategy was largely a continuation of Carter’s. In the midst of deliberations regarding the 1982 budget, the National Security Council (NSC) compiled National Security Division Directive (NSDD) 26, which spelled out the objectives of Carter’s Presidential Directive 41 and was designed to promote deterrence, improve natural disaster preparedness, and reduce the possibility of coercion by enemy forces.208 The unclassified version of NSDD 26 states: “it is a matter of national priority that the United States have a Civil Defense program which provides for the survival of the U.S. population.”209 However, NSDD 26 went further than PD 41 by stipulating a concrete deadline in 1989 for plans to protect the population, and it mandated that civil defense leaders investigate and enhance protection measures for critical industries in case of attack.210 Furthermore, NSDD 26 for the first time supported research into the development of strategies to ensure economic survival in the event of a nuclear attack.211 However, drawing upon the CRPs of his predecessors, Reagan continued to promote evacuation the primary strategy for civil defense. During this period nuclear preparedness became a top priority for FEMA

Congress and the Administration came into conflict in February 1982, when the President requested $4.2 billion for a seven-year plan to massively boost civil defense programs.213 Congress did not react positively to this request, particularly because it seemed to be part of Reagan’s hawkish stance on Cold War diplomacy.214 For example, the House Committee on Appropriations criticized FEMA’s dependence on evacuation planning at the expense of other preparedness programs and suggested that more attention be paid to peacetime disaster preparation. Expressing their disagreement with FEMA’s plans, Congress allocated only $147.9 million to cover FEMA’s 1983 budget, about 58% of what the agency had requested.215 In 1984 and 1985, Congress again blocked requests for funding increases.

In 1983, FEMA responded to the Congressional push for more peacetime disaster preparation with plans for an Integrated Emergency Management System (IEMS) to develop full all-hazard preparedness plans at the Federal level.217 Under the IEMS, State civil defense planners would facilitate the development of multi hazard preparedness plans based on threats faced by specific localities.218 According to the IEMS, this all-hazards approach included “direction, control and warning systems which are common to the full range of emergencies from small isolated events to the ultimate emergency – war.”219 Despite this innovative attempt to integrate civil defense and disaster preparedness concerns, Congress was not sufficiently convinced that the IEMS would effectively address the management of all hazard preparedness, and therefore never met requested FEMA funding levels. Cold War diplomacy continued to play a role in civil defense decisions under Reagan. President Reagan supported neither the doctrine of mutual assured destruction nor the détente that had been a centerpiece of the Carter Administration.220 On March 23, 1983 Reagan openly rejected mutual assured destruction with his speech proposing the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI). SDI focused on using ground-based and space based systems to protect the United States from attack by strategic nuclear ballistic missiles.221 SDI flew in the face of the 1972 SALT I agreement banning strategic defenses, and it demonstrated a shift towards more proactive and aggressive defensive measures.

The final years of the Reagan Administration saw a number of actions intended to allay concerns regarding non-attack preparedness. The Meese Memorandum (Executive Order 12656), signed in 1986, delegated lead response roles to certain Federal agencies, depending on the type of disaster.222 On November 23, 1988 the Disaster Relief Act of 1974 was amended to become what is now known as the Stafford Act, resulting in a clearer definition of FEMA’s role in emergency management. The Act defined the disaster declaration process and provided the statutory authority for Federal assistance during a disaster. The agency’s role in disaster response would be tested and debated in the years to come.

Bush Administration (1989-1993) In the year after George H.W. Bush took office, several natural disasters challenged the Nation’s nascent approach to all-hazards preparedness. On March 24, 1989, 11 million gallons of crude oil spilled into Prince William Sound in the Gulf of Alaska from the Exxon Valdez oil tanker.223 It was the largest oil spill in U.S. history, and the Administration was ill-prepared to manage an environmental crisis of such large scale. Instead of using FEMA through the Stafford Act to coordinate the response, Bush invoked the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, under which the Environmental Protection Agency and Coast Guard managed the event. The Administration drew much criticism for the poor response

On September 13, 1989, Hurricane Hugo struck the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, and South Carolina, inflicting significant damage. This time Bush chose to send Manuel Lujan, Secretary of the Interior, to assess the damage and provide additional executive oversight.225 FEMA’s participation in the response was plagued by shortages of properly trained personnel, communication problems, and a lack of coordination.226 Within a month of Hurricane Hugo, the Loma Prieta earthquake struck northern California causing an estimated $6 billion in damage. Already stretched thin from dealing with the Hurricane Hugo recovery, FEMA’s response continued to be hindered by coordination and staffing problems. Again, President Bush appointed a Cabinet-level representative, Secretary of Transportation Samuel Skinner, to oversee recovery operations, and again FEMA’s contribution to response and recovery was judged inadequate.

The dissatisfaction with FEMA’s response to the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill, Hurricane Hugo, and the Loma Prieta Earthquake led FEMA to begin developing the Federal Response Plan (FRP) in November 1990.228 Drawing from the Incident Command System and Incident Management System framework, the FRP defined how 27 Federal agencies and the American Red Cross would respond to the needs of State and local governments when they were overwhelmed by a disaster. The plan used a functional approach to define the types of assistance (such as food, communications, and transportation) that would be provided by the Federal government to address the consequences of disaster.

By the second year of the Bush administration, significant political changes were occurring. The Berlin Wall fell in 1989, followed shortly by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the fall of communist governments across Eastern Europe. The Cold War had come to a rapid and unanticipated end, and the threat of a strategic nuclear attack on the United States diminished significantly almost overnight. As a result, civil defense in the traditional sense was no longer a major priority for emergency planners or Congress. With the recent onslaught of natural and man-made disasters top-of-mind, FEMA planners began to adopt the idea of a true all-hazards approach to disaster preparedness. In March of 1992, President Bush signed National Security Directive 66 instructing FEMA to develop a multi-hazard approach to emergency management, combining civil defense preparedness with natural and man-made disaster preparedness

Testifying before the Armed Services Subcommittee Hearing on Civil Defense on May 6, 1992, Grant Peterson, Associate Director for State and Local Programs at FEMA, reported that:

The President has approved a new civil defense policy…The new policy acknowledges significant changes in the range of threats, and eliminates the heavy emphasis on nuclear attack. The policy recognizes the need for civil defense to address all forms of catastrophic emergencies, all hazards, and the consequences of those hazards. The new policy increases the emphasis on preparedness to respond to the consequences of all emergencies regardless of their cause. All-hazards consequence management recognizes that regardless of the cause of an emergency situation, certain very basic capabilities are necessary to respond and that planning efforts and resources should be focused on developing the capabilities necessary to respond to all the common effects of all hazards.

In August 1992, Hurricane Andrew hit south Florida and the central Louisiana coast. President Bush once again appointed a Cabinet-level representative, Secretary of Transportation Andrew Card, to coordinate Federal relief efforts.232 Unfortunately, this additional oversight did not result in improved performance as “government at all levels was slow to comprehend the scope of the disaster.”233 And despite the presence of the FRP, FEMA and the other agencies involved in the response and recovery faced the same kinds of coordination and logistical problems they had three years prior. FEMA was strongly criticized by Congress for its poor performance.

As a result of this criticism, FEMA was instructed by Congress to contract with the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) to conduct a study of the Federal, State, and local level capacity to respond to major natural disasters.234 Issued in February 1993, NAPA’s assessment, Coping With Catastrophe, detailed the obstacles facing emergency management at all levels of government and made recommendations to improve FEMA’s ability to prepare and respond to disasters. NAPA concluded that, “a small independent agency could coordinate the federal response to major natural disasters…but only if the White House and Congress take significant steps to make it a viable institution.”235 Because of the timing of the report, it was left to the Clinton Administration to evaluate the findings and implement changes to make FEMA more effective.

Clinton Administration (1993-2001) Upon taking office, President Bill Clinton appointed James Lee Witt director of FEMA. Witt, the former Director of Emergency Management for the State of Arkansas, immediately reorganized FEMA.236 He created three functional directorates corresponding to the major phases of emergency management: Mitigation; Preparedness; Training and Exercise; and Response and Recovery.237 In February of 1996, Clinton elevated the FEMA directorship to Cabinet-level status, improving the line of communication between the Director and the President.

The shift in emergency preparedness towards an all-hazards approach allowed FEMA to focus on addressing natural disasters without having to fear negative political reactions from advocates of civil defense.239 The Agency’s Mitigation Directorate, for example, focused many of its early programs on hazards such as flooding and earthquakes.240 At the same time, however, recognition of the threat of terrorist attacks inside the United States was beginning to emerge. In 1993, Congress included a joint resolution in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) that called for FEMA to develop “a capability for early detection and warning of and response to: potential terrorist use of chemical or biological agents or weapons; and emergencies or natural disasters involving industrial chemicals or the widespread outbreak of disease.”

As evidenced by this resolution, Congress was becoming increasingly concerned about the threat posed by terrorist organizations and technological disasters. Much of this concern resulted from the World Trade Center bombing earlier that year, in which 6 people were killed and 1,042 were wounded. The blast left a five story deep crater and caused $500 million in damages

In November 1994, the Federal Civil Defense Act of 1950 was repealed and all remnants of civil defense authority were transferred to Title VI of the Stafford Act.242 This completed the evolution of civil defense into an all-hazards approach to preparedness. FEMA now had the statutory responsibility for coordinating a comprehensive emergency preparedness system to deal with all types of disasters. Title VI also ended all Armed Services Committee oversight over FEMA and significantly reduced the priority of national security programs within FEMA. Money authorized by the Civil Defense Act was reallocated to natural disaster and all hazards programs, and more than 100 defense and security staff members were reassigned

The period between 1995 and 1996 saw a series of major terrorist attacks launched domestically and abroad, which further influenced U.S. preparedness policies. In March 1995, the Japanese religious cult Aum Shinrikyo released sarin nerve gas on five separate cars of three different subway lines in Tokyo. Twelve people were killed and thousands were injured. One month later, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols detonated a truck bomb at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, killing 169 people. On June 25, 1996 the Khobar Towers, a U.S. military facility in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia was bombed, killing 19 Americans.

These events had a profound effect on U.S. lawmakers and the Administration.245 Two days after the bombing of the Khobar Towers, the Senate adopted an amendment aimed at preventing terrorists from using nuclear, chemical, or biological weapons in the United States.246 In September Congress passed the NDAA for fiscal year 1997, which included the Defense Against Weapons of Mass Destruction Act commonly known as the Nunn-Lugar-Domenici Act.247 This Act required DOD to provide civilian agencies at all levels of government training and expert advice on appropriate responses to the use of a weapon of mass destruction (WMD) against the American public. Lawmakers originally planned to have FEMA lead the training and provide equipment; however, FEMA officials had testified that only DOD had the necessary knowledge and assets .

As a result of the Nunn-Lugar-Domenici legislation, Metropolitan Medical Strike Force Teams were created, as well as a domestic terrorism rapid response team, whose purpose was to aid State and local officials in WMD response.249 Three years later, WMD preparedness was transferred from DOD to the Office of Domestic Preparedness (ODP) within the Department of Justice (DOJ).250 In 1999, DOD also established 10 National Guard Rapid Assessment and Initial Detection (RAID) teams, which served to provide technical expertise and equipment to deal with a WMD attack.251 The unanticipated result of these actions was a new fragmentation of responsibility for civilian preparedness programs. Despite its overtures toward all-hazards preparedness, many of FEMA’s efforts remained focused on natural disasters. Meanwhile, DOD through its RAID teams, and DOJ through ODP, became increasingly involved in preparations for and responses to WMD threats.

Apart from these efforts, as the century came to a close, a new concept of homeland security began to emerge. Presidential Decision Directive (PDD) 62, signed in May 1998, created the Office of the National Coordinator for Security, Infrastructure Protection, and Counter-Terrorism within the Executive Office of the President. This office was designed to coordinate counterterrorism policy, preparedness, and consequence management.252 Later that same year, President Clinton issued PDD 63 on Critical Infrastructure Protection. PDD 63 established principles for protecting the nation by minimizing the threat of smaller-scale terrorist attacks against information technology and geographically distributed supply chains that could cascade and disrupt entire sectors of the economy.253 In the absence of a centralized authority for homeland security, Federal agencies were designated as lead agencies in their sector of expertise. The lead agencies were directed to develop sector-specific Information Sharing and Analysis Centers to coordinate efforts with the private sector. PDD 63 also required the creation of a National Infrastructure Assurance Plan.

At the same time, the U.S. Commission on National Security in the 21st Century, chartered by DOD, and known as the Hart Rudman Commission, began to reexamine U.S. national security policies.254 One of the Commission’s recommendations was the creation of a Cabinet-level National Homeland Security Agency responsible for planning, coordinating, and integrating various U.S. government activities involved in “homeland security”. The commission defined homeland security as “the protection of the territory, critical infrastructures, and citizens of the United States by Federal, State, and local government entities from the threat or use of chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, cyber, or conventional weapons by military or other means.” Legislation toward this end was introduced on March 29, 2001, but hearings continued through April of 2001 without passage of the legislation.

Another influential commission formed during the latter stages of the Clinton Administration was the Gilmore Commission, chaired by Virginia Governor Jim Gilmore. The Commission, officially known as the Advisory Panel to Assess Domestic Response Capabilities for Terrorism Involving Weapons of Mass Destruction, developed and delivered a series of five reports to the President and Congress between 1999 and 2003.256 Of the Gilmore Commission's 164 recommendations, 146 were adopted in whole or in part 257, including creation of a fusion center to integrate and analyze all intelligence pertaining to terrorism and counterterrorism and the creation of a civil liberties oversight board.258 However, the impetus to implement many of these recommendations only occurred following the series of devastating attacks on the U.S. homeland that occurred during the initial months of the next administration.

Bush Administration (2001-Present)

The initial months of George W. Bush’s presidency saw a general continuation of existing homeland security policies. Prior to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, OMB summarized homeland security as focused on three objectives: counterterrorism, defense against WMD, and the protection of critical infrastructure The new Administration did implement changes that affected how national security and homeland security policies would be generated. The Administration abolished the system of ad hoc interagency working groups used by Clinton to address homeland security issues and replaced them with Policy Coordination Committees within the National Security Council. A Counterterrorism and National Preparedness Policy Coordinating Committee was established that was composed of four working groups: Continuity of Federal Operations, Counterterrorism and Security, Preparedness and WMD, and Information Infrastructure Protection and Assurance.260 The goal of this reorganization was to create a more formalized structure to deal with threats to the homeland.

Then came the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. In their wake, there was near universal agreement within the Federal government that homeland security required a major reassessment, increased funding, and administrative reorganization. In October 2001, the White House Office of Homeland Security was established via executive order to work with Executive departments and agencies to develop and coordinate the implementation of a comprehensive national strategy to secure the United States from terrorist threats or attacks.261 President Bush chose Pennsylvania Governor Tom Ridge to lead the new Office. In March 2002 another executive order created the Homeland Security Advisory Council to advise the President on homeland security matters. The Council, located within the Executive Office of the President, is comprised of leaders from State and local government, first responder communities, the private sector, and academia.

In his 2002 State of the Union address, the President announced the establishment of the USA Freedom Corps to promote a culture of service, citizenship, and responsibility in America. Under the Freedom Corps initiative, the White House established Citizen Corps within FEMA to engage individual citizens through education, training, and volunteer service to make communities better prepared to prevent, protect, respond, and recover from all-hazards. Citizen Corps involved Americans in programs such as Community Emergency Response Teams, Fire Corps, Neighborhood Watch, Medical Reserve Corps, and Volunteers in Police Service.