On 29 January 2014, at 4PM, Retired Police Officer James Edward Mitchell passed away at his home in Hanover, PA. After a visit from his son, Jim closed his eyes and peacefully passed away; his daughter, Marry Harrell, put her hand on his and realized he had gone. It had been a long struggle, but in the end Jim passed with dignity and strength. Officer Jim Mitchell was good police, a good man, and a good friend; he will always be missed.

Through this page, he will never be forgotten, as we will always have a place to come visit our brother, Police Officer Jim Mitchell. God Bless, and Rest in Peace Jim We all love you

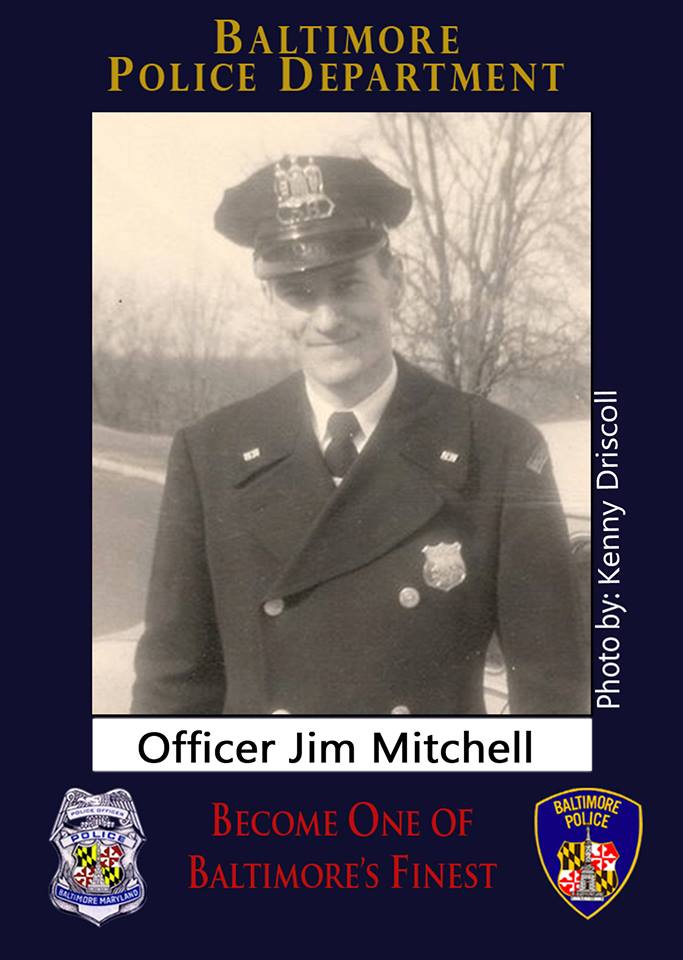

Officer Jim Mitchell BPD Trading Card

Circa 1956 with a 1948 Buick

Circa 1956 with a 1948 Buick

1957 Jim Mitchell

1957 Jim Mitchell

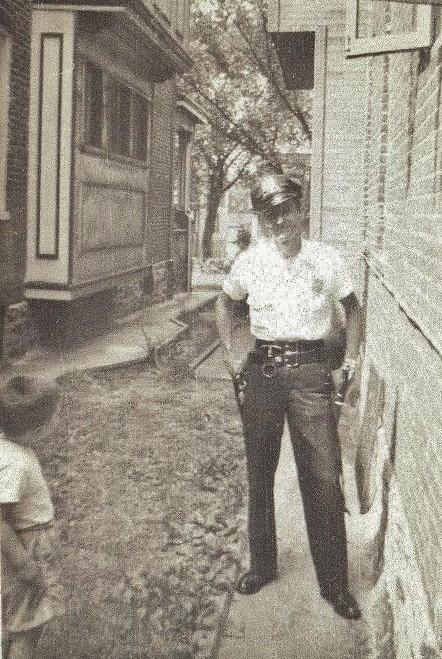

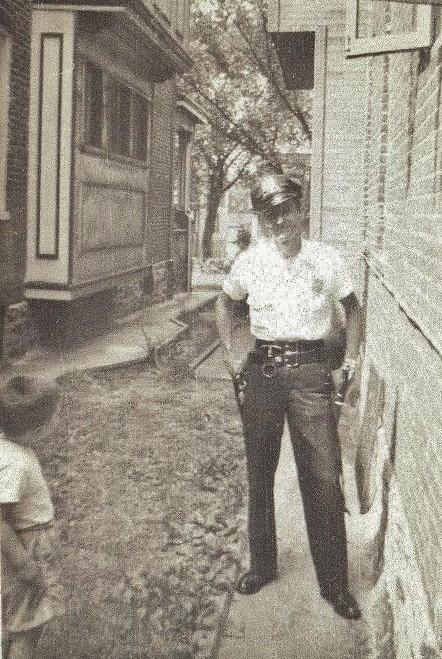

A nightstick, his claw and that smile

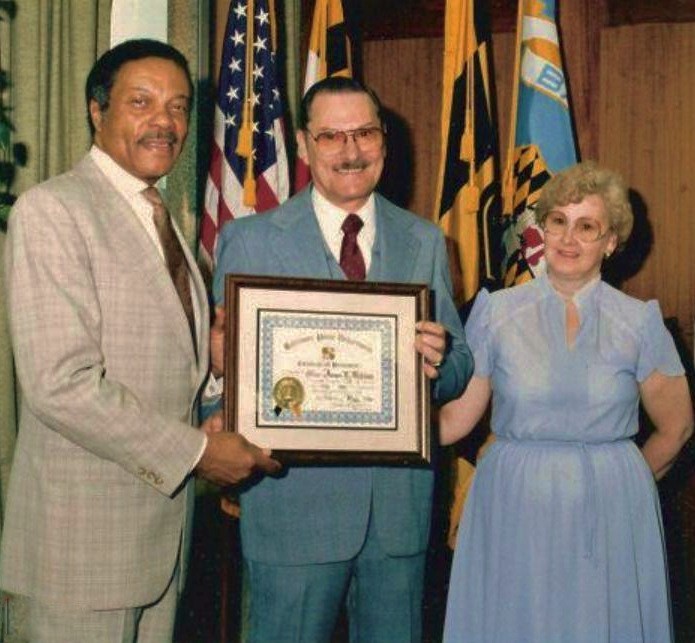

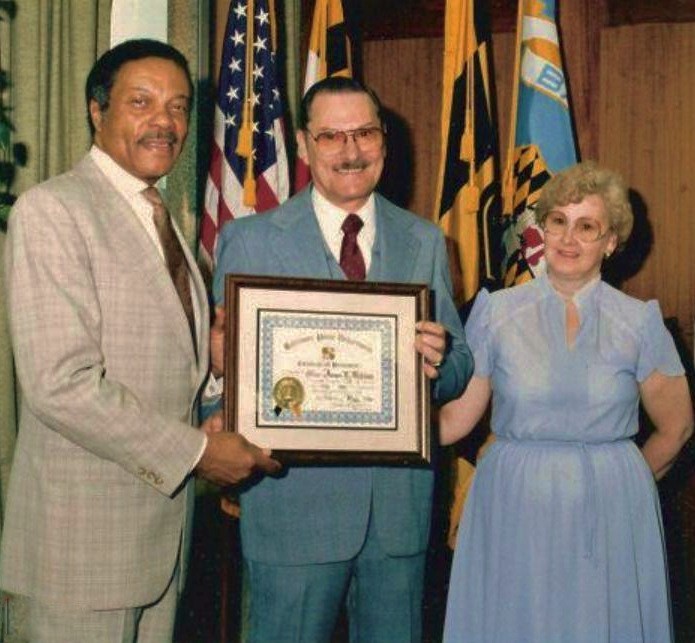

Commissioner Bishop Robinson

Retirement 1986

When Bishop Robinson passed away (7 January 2014) WMAR Channel 2 Baltimore did a story on "The Bishop", and used this picture among others to tell Commissioner Robinson's Story. I had written Jim, and Jim wrote the following:

It all started back in 1956 when Ed Tilghman & I were in the academy together & we both started together in the old NW on Pennsylvania Ave. After we moved to WD he eventually got promoted to Sergeant. He became our squad leader and he made his OIC. Much later he was promoted Major & came back to command the WD. During this period is when there was an opening for a new turnkey, I put in for it and got it. I worked along with Griffin Dobyns. Again Tilghman was promoted he was replaced with Major Boles. In 1981 I had a heart attack, I was placed on light duty by Major Boles and before long I had become his errand boy; Something that I disposed. Eventually he wanted to get rid of his light duty personnel and I was transferred to Headquarters Security. One day while I was in the security booth of the garage on Frederick Street my good friend Tilghman came through and saw me, he stopped and asked why I was there. After explaining everything to him, he said he was going to get back with me. About a week later I got a phone call a home from Lt O'Hara who informed me that he had set up an appointment to meet with Tilghman, as Tilghman wanted to know if I would be interested in a job offer he had me. After hearing what he wanted me to do I quickly accepted his offer. I was assigned to work with Sgt. Daughtery in a unit that would constitute the handling all the deaths in the department. We had an office on the 7th floor, and whenever an officer died, natural, retired, line of duty, etc we were notified, and we would start our process. We contacted family members of deceased to see what there needs were and if necessary we contacted districts to provide pall bearers, contacted funeral homes and whatever else was necessary. It was a sad, but heartwarming job, and I enjoyed helping these families during their trying times. We also had a retiree desk in the office where a volunteered officer would come in several times a week and assist with any information that anyone might call in for about retirement. After I retired I always hoped that someone else would continue this position. Sgt Daugherty retired a couple of months after me. Not long after that Tilghman was promoted to Police Commissioner, and not too much longer after that he died. I hope that was not too long or boring. (Jim Mitchell)

Not boring at all, Jim is an amazing man, an amazing police officer and has an amazing memory. I am honored to call him a friend and thankful that he would take the time to write this.

Police Officer Jim Mitchell,

“When I joined, it wasn’t racist for the white officers not to like the black and the black not to like the white. It was just the way it was; times were different. It may be hard for someone today to understand, but today we know there is no difference between a white man and a black man other than skin color. Back then, the “N” word was a commonly used word; I used it, my bosses used it, and we wrote it in police reports. It seemed like newspapers up until the 1970s referred to black men as "Negros" and women as "Negresses." Martin Luther King referred to a black man as a Negro, so Negro wasn’t an issue, and back then the “N” wasn’t an issue, or at least it wasn’t as obvious. Then we were segregated, and as such, we didn’t know better; it could be considered propaganda, education, or a lack of an honest education. But black men didn’t like us, and we didn’t like them. I drove a milk truck before joining the police force, and I was at Whitelock St. near North Ave.; it was in the early morning, and I turned the corner. You know, there’s like a little corner there where there is this blind spot, and I was in this big milk truck when I took the corner, and I hit a guy; he popped up off the street and said, “I’m OK... I’m Ok, you can go, I’m Ok” well, I wasn’t new to things like that, and didn’t want to lose my job, so I went around to Pennsylvania Ave. down by Gold St. and flagged down a police officer, he was with another officer and I told them I turned the corner and hit a guy, I told him the guy said, he was Ok and told me I could go, but I wanted to make sure I told someone, I didn’t want to be accused of hit and run, the officer said, (and because he didn’t say, “N – word”, and I want you to fully understand, I will say it the way he did.. he said, “Was it a nigger?”, and I didn’t know any better at the time, so I said, “Yes!” And he said, “Don’t worry about it; you can just go back to doing what you were doing!” So I went back to my route, and when I went past that corner, I saw the guy standing there with another officer. He pointed to me and said, I was the one that hit him, and I just left! The Officer flagged me down and asked what happened. I told him what happened and that it was dark; he was dressed in all black (well, they could see that; he was still wearing the same clothes, and he was dark skinned!) I told the officer what happened and that I didn’t just leave; I went over to Pennsylvania Ave. and Gold and told some officers around there what had happened. The guy wasn’t hurt; he was walking around fine. The officers assumed he was just trying to roll me or the company I worked for, and that at first, when he claimed he was ok and sent me on my way, someone must have told him he could get money for being hit, so he stopped the first officer he could find. Back then, the police didn’t like to be used in that way, and times were different. Today, I know it was wrong for them to have called him an “N” word and not to have corrected them, but my knowing that didn’t come until years later after joining the police. Driving the milk truck wasn’t a way to make a living; it didn’t pay well, and I was robbed several times. I figured if I was going to be in those tough neighborhoods, I might as well have a gun. So me and an old army buddy went down to the police department and joined; we went down to headquarters and applied for the job; shortly after that, they hired both of us. We both went through the academy; I was assigned to the Northeastern; I forgot where he went; we talked every so often, but for the most part, we lost contact, except one time: I met him down Lexington Market, and he had heard I wasn’t married anymore; he told me I should go talk to Doris, and I said she’s married; he said, no, her and her husband weren’t working out, so they are separated; well, I contacted her. Doris and I dated before I went off to the Army, and she had moved on. I met a nurse, and we were married. My marriage didn’t work out, and since Doris’ Marriage didn’t work out, I went and looked her up, and we have been together ever since. 43 years, 4 kids, 8 stepchildren, 21 grandchildren, 26 great-grandchildren, and 5 great-great grandchildren later, and we are where we are today. But back to his leaving the academy: while still at the armory after graduation, he was called aside by a Sergeant and told he wouldn’t be going to the Northeastern and that he and a few of the others would be detailed to the Northwestern District. "Well, I didn’t mind; back then, the Northeastern was called the country club, and I didn’t want that; I wanted the action, so I was glad to go to the Northwest; I liked it. After a few months, I went to my sergeant. (Back then, we didn’t have majors; we had Captains, and under the Captain was the Lieutenant.) It was a chain of command, and you didn’t break that chain. So anyway, I liked Northwestern, I had made friends, and I liked the posts where I worked. I was young and full of piss and vinegar and liked the action, so I went to my Sergeant and asked if I could stay and if I could make the detail permanent. The Sergeant said, “Are you sure?” and I told him I was positive and that I wanted to stay. So the sergeant said, We could find out, and he went in and talked to the Administrative Lieutenant. In those days, we had four Lieutenants in the district: One for each shift (the Shift Lieutenants) and an Administrative Lieutenant that oversaw everything doing administrative work in the district (he took care of transfers). The Administrative Lieutenant called me into his office and asked me if it was true that I wanted to stay. I told him it was! He then asked, “Why would you want to stay here?” I explained that I worked the area before joining the force, I liked the guys I was working with, and I enjoyed the action and wanted to stay. He said he wouldn’t ask twice and that he would take care of the paperwork. That was the last I heard of it; a few months later, it was official that I was transferred to Northwestern.

It was before desegregation

It was before desegregation, and while we had black officers, they didn’t drive cars, they couldn’t work certain areas, they hated us, and we hated them... I remember when they desegregated; it was 1966, and we were not happy. I mean, we all had regular partners, guys we worked with, guys we knew and trusted; our partners were guys we knew had our backs, and we didn’t know the black officers; we didn’t know if they would fight when we needed someone to fight, and back then there were a lot of fights. So my Sergeant pulled me aside and told me, “If this nigger goes to sleep, I want you to call me; I want you to tell me so I can come out and catch him, and then I can fire his black ass, and we can put an end to this bull shit!” So I said, “Yes, sir!” and I tried. I was ready to turn him in; I didn’t know him, and all I knew was what I had heard. About halfway through the shift (We were working at midnight), around 3 a.m., it would have been time to hit the hole. (Back then, when we were going to go to sleep, we called it “Hitting the hole”!) but I didn’t know the guy, so I just kept driving around, and finally he said to me, “Do you boys hit the hole?” I said, “Hit the hole? I’m sorry, I don’t know what you mean!” (Of course I did, but I couldn’t have him know that!). So he said, “Yeah, the hole, you know, go to sleep!” So I said, “No, but if that’s what you want to do, just tell me where to go.” So he directed me as to where to go, and we wound up under a bridge, but he wouldn’t go to sleep. I was hoping he would, so I could turn him in and get my regular partner back. But we just sat there, staring up at the bottom of an old bridge. Finally, I had to go to one of the bars to help them close the place. While I was in there, I looked out the door and he was sleeping, so I called it in, and the Sergeant came right out, but when he drove by, my new partner was wide awake, and the Sergeant just kept driving right on by. To this day, I often wonder if he faked sleeping to see what I would do, but it doesn’t matter because by the end of the second week, we had started talking, and I learned about his wife and kids. He had a wife and two kids, and I had a wife and kids. He told me his wife worked at a makeup counter downtown, and my wife worked at a Jewelry counter. Other than skin color and where we lived and grew up, we were the same. Then we got into a fight, arresting some black guy, and I didn’t know if he would help, but he was right in there, and he was as good and as hard a fighter as any partner I had ever had. By the end of the first month, we had become real partners, and there was no way in the world I would have turned him in for sleeping. I was actually sorry they integrated us at first, but by the end of the second week, I was becoming more interested in working together, and again, I have to point out that this wasn’t the 1990s or 2000; this was 1966; I came on in the mid-50s; times were different; the internet wasn’t around; television wasn’t even what it is today. We were not educated to know anything but what we were told or what we read in the papers, and it wasn’t just us; the black officers hated us white officers too. They hated us to a point, and I didn’t find this out until years later, but that night when that officer asked me if we were going to go in the hole, and my Sergeant told me to turn him in for sleeping, his sergeant told him the same. So basically, the white officer’s sergeants and the black officer’s sergeants hated each other, but they thought alike; they both came up with the same plan to have their officers turn in their partners so he could have him fired, and then we could return to the way it was. You have to understand that, just in case it isn’t clear, the white officers might not have wanted to work with the black officers, but the black officers didn’t want to work with the white officers either. What the black officers wanted was to be able to work any post, drive patrol cars, wear uniforms, advance in the ranks, etc. The department itself was not fully integrated until 1966. Prior to 1966, black officers were limited to foot patrol; they were barred from the use of squad cars. These officers were quarantined in rank, barred from patrolling in certain white neighborhoods, and would often only be given specialty assignments in positions in the narcotics division or as undercover plainclothes officers. They didn’t want to work with white officers, but they did want to be treated equally. They hated us; they didn’t trust us, but we were all the same. That’s why I say it wasn’t racist, unless they were racist too, and I don’t think that was the case. I think racism is having the information available and ignoring the facts to believe what you want. Or not wanting to ever become friends, even after you know we are the same. Once we worked together, we liked each other. I have a picture of my partner hanging on the wall in my living room. I went to his funeral, his kids graduations, and weddings. We would have been friends earlier, but we didn’t know, and that wasn’t either of our faults; society and the department kept us apart; it was in the rules, and when those were the rules, they didn’t come near us, and we didn’t go near them; they hated us, and we hated them; we both were misinformed about the other. I know I said it before, but as much as I hated the idea of integration at first, I worked about 10 or 11 years before integration and nearly 20 years after; those 20 years were much better than the first 10 or 11. I made a lot of friends, both black and white, and I know we would have missed out on a lot had we stayed segregated.

By the way, Kenny, I only used the “N” word in this to help tell the story. I used the “N” word before desegregation, as most people did, and as we grew, we learned the word had left our vocabulary. The thing is, once we learn and once we knew better, we either grew or we don't, and where we grew, things get better. There were people who chose to keep hating each other, and things continued down the wrong road. But for most of us, things changed. I hope this helps tell the story. I didn’t want to sugarcoat anything. That is a big problem today; no one wants to tell it like it is. All anyone has to do is read a newspaper from the 1940s to maybe about the mid- to late-70s.

Interesting. I spoke to a young lady who thinks this story was referring to her dad. She saw the story on this site and said her dad told her the same story for years as a kid, but from the African American Officer's point of view. He has since died, so I won't use his name, but I will say this: according to her, the African American officers of the time (from what her dad told her) were proud of being part of the police that broke the color barrier. They were the Jackie Robinsons of the Baltimore Police Department. They put up with a lot of ugly times to make things what they are today. When I came on in 1987, I had several African American partners; race wasn’t an issue; we did our jobs, we fought together, laughed together, and were friends. I can only imagine how it was for everyone involved and am glad to have come on when I did. We have come a long way.

If you have a story, pictures, or information you would like to add to the site, please send them our way, and as always, thank you for visiting our site.

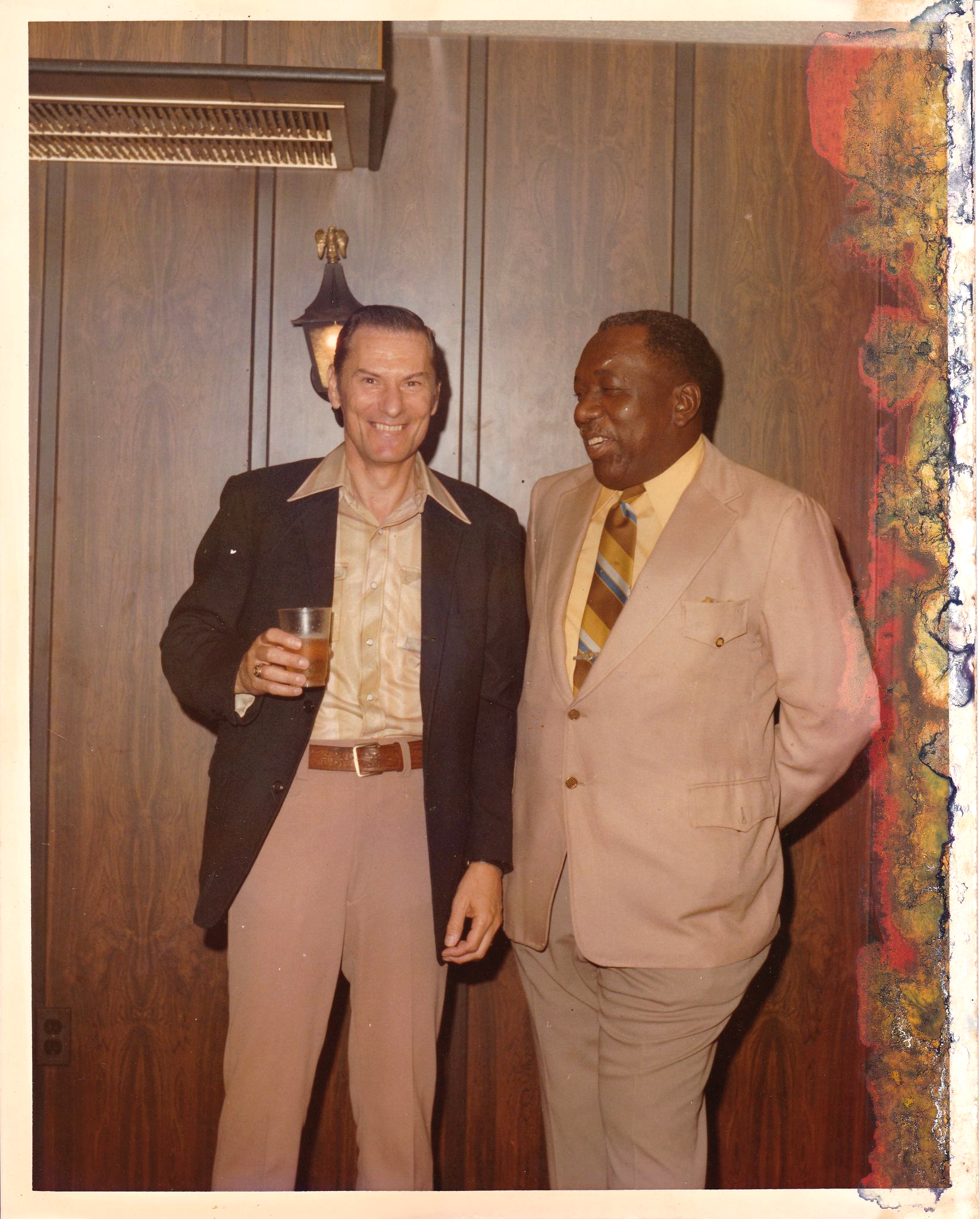

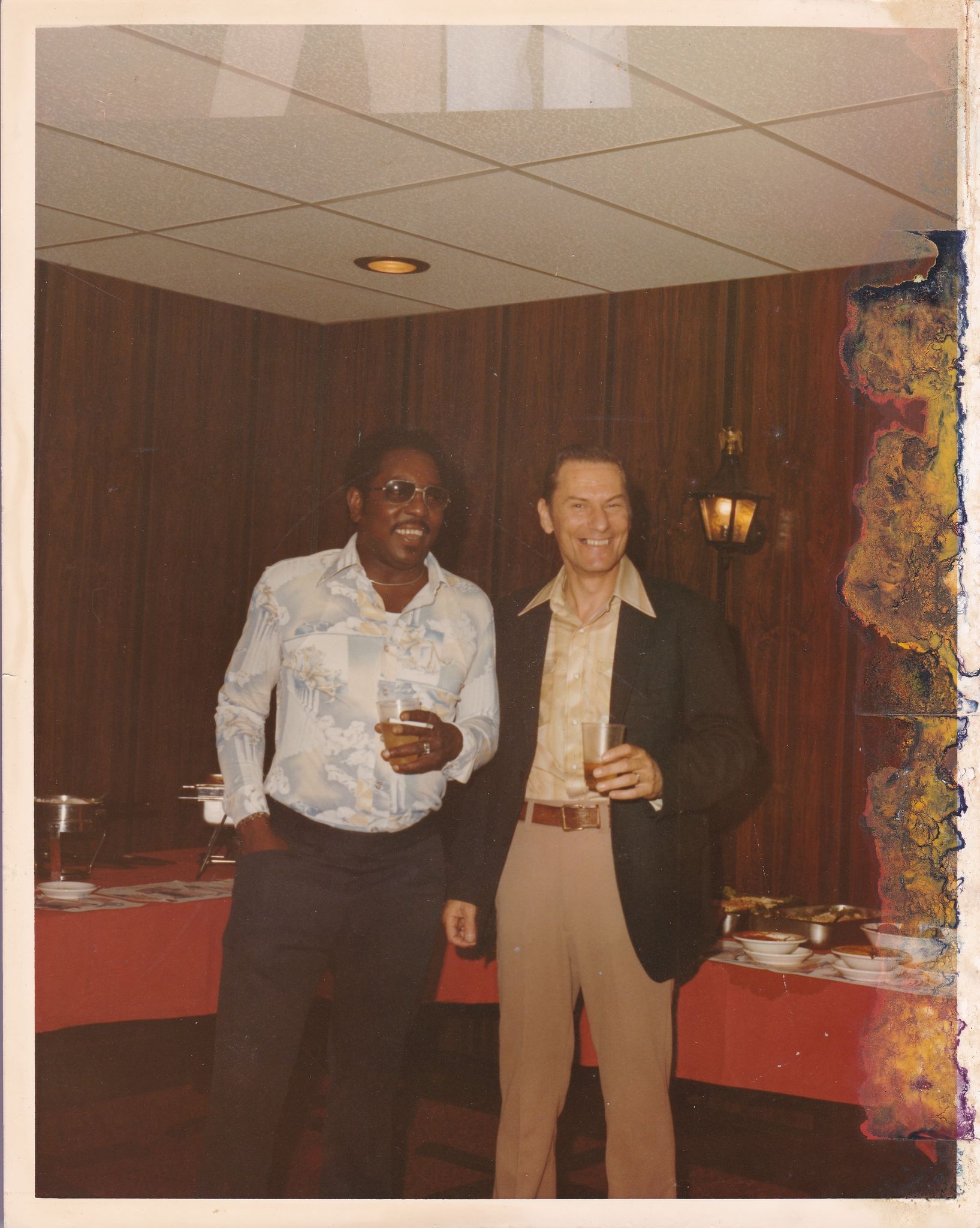

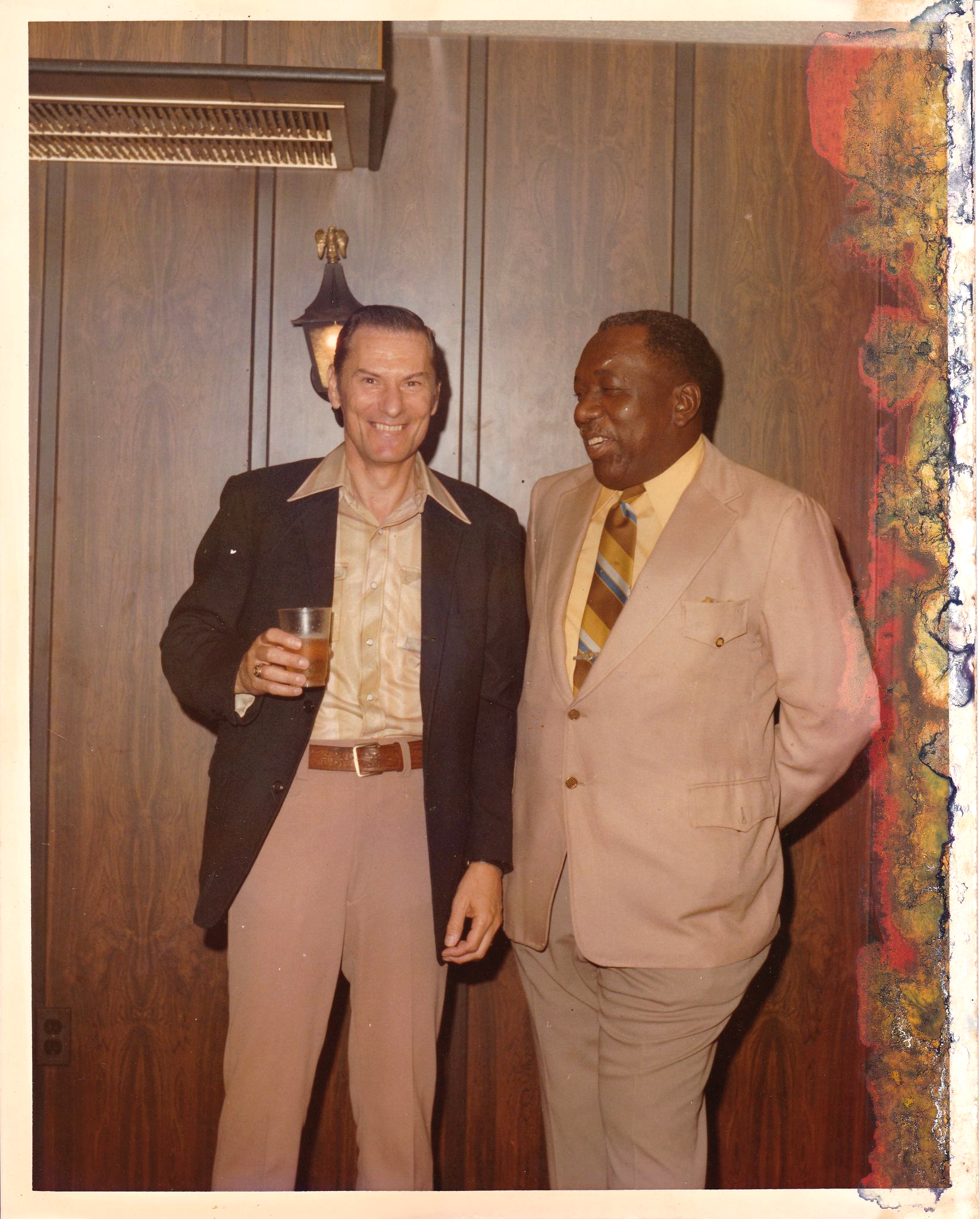

Jim and Frank Myers

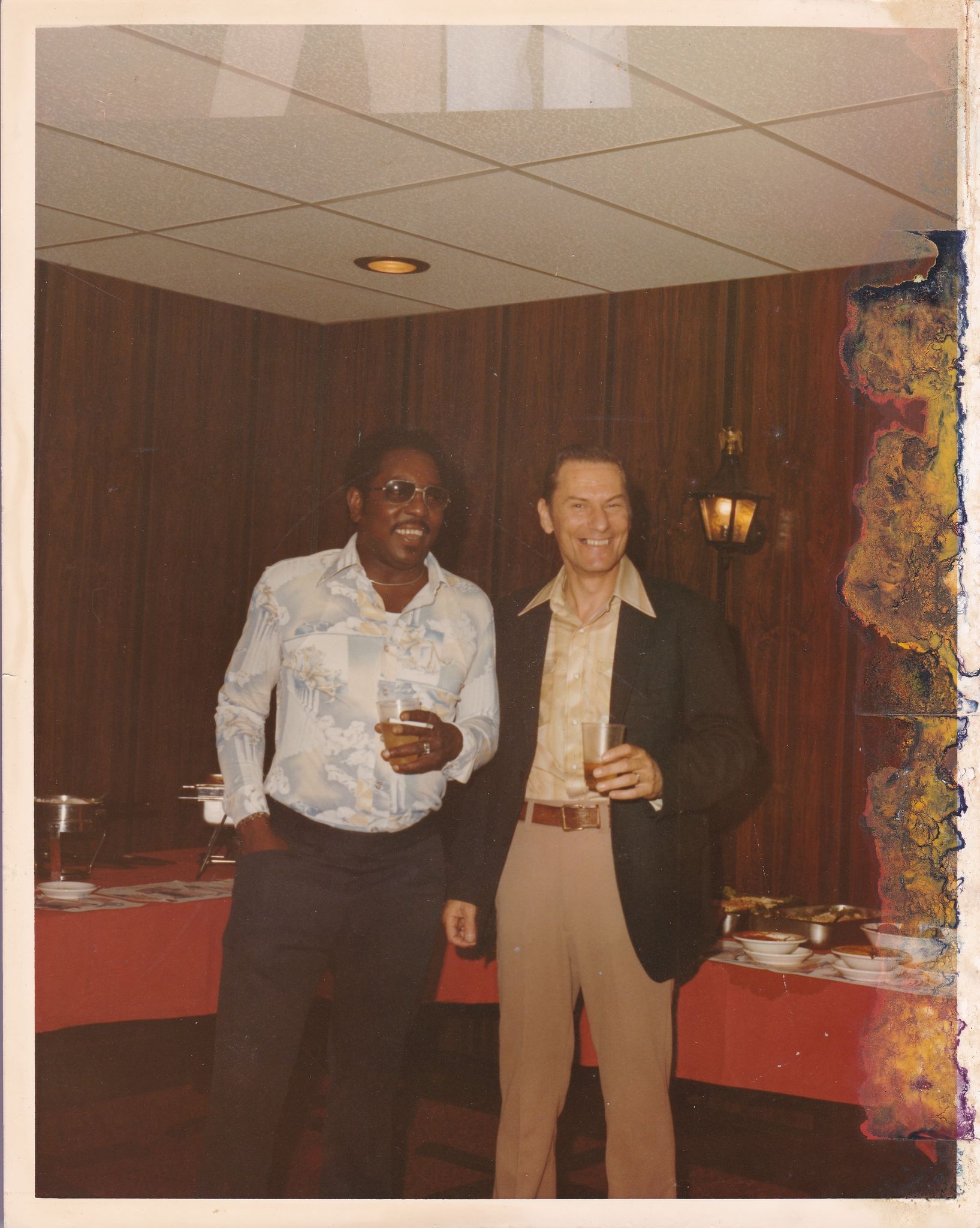

Jim and Elmer Moore

First from the left is Mickey Finn, Fourth is Jules Sass all from the NWD

First from the left is Tom Coppinger, third is Lou Distefano, fourth is Dickie Moore fourth, and fifth is Eddie Johnson all from CD

Circa 1956 with a 1948 Buick

Circa 1956 with a 1948 Buick