African Americans in the Baltimore Police Department

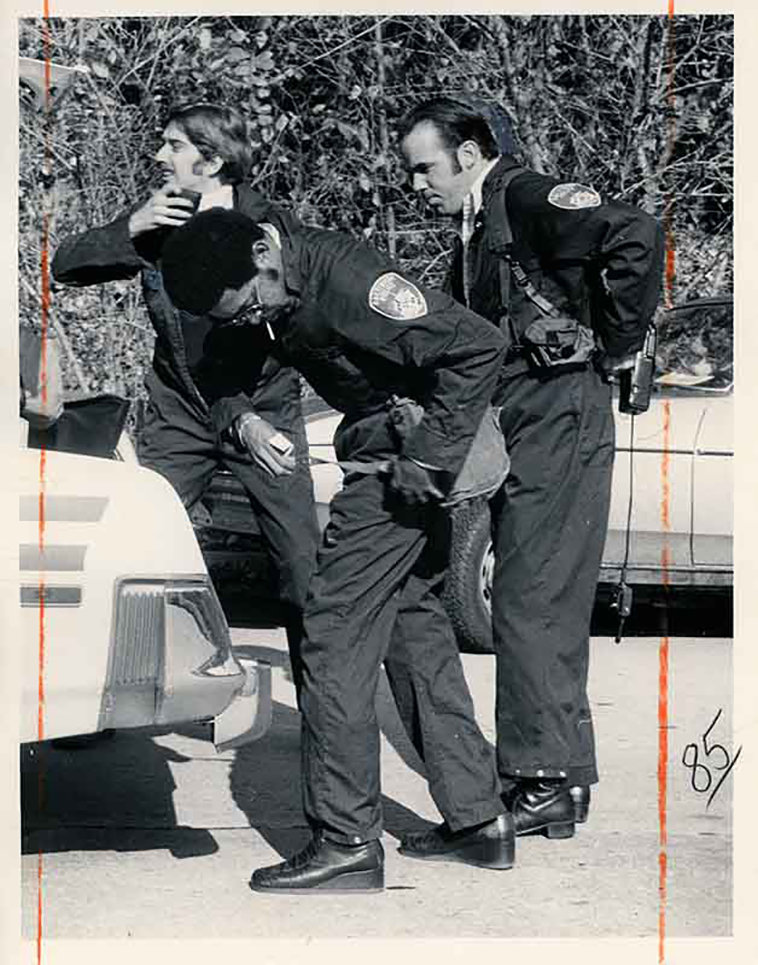

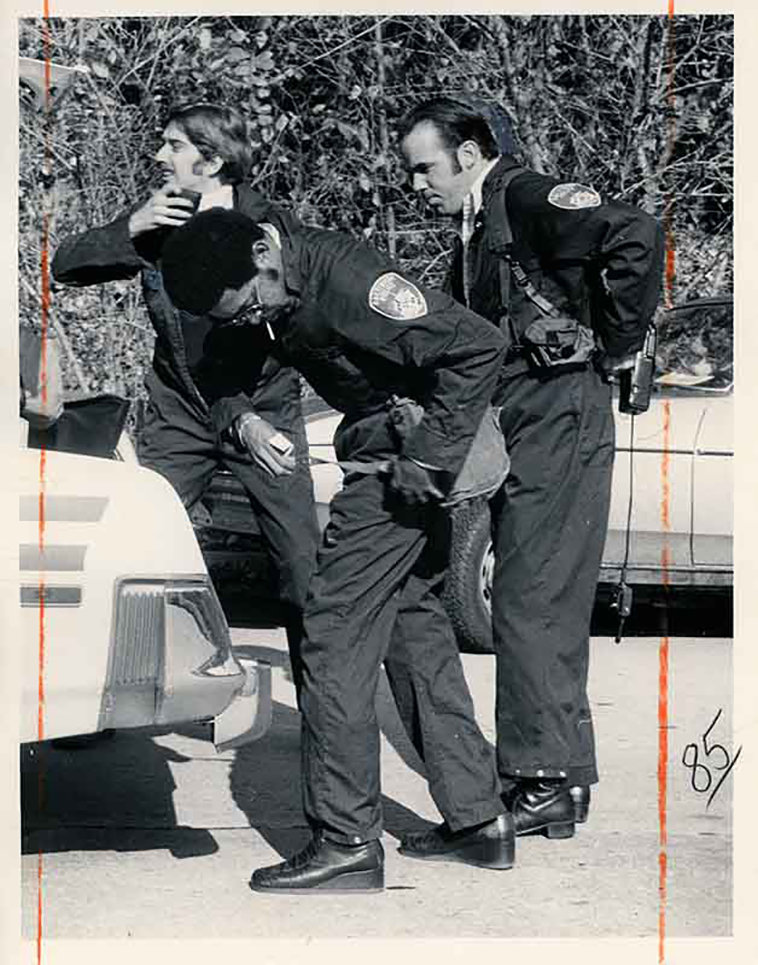

From our Private Collection Showing Founding members of Baltimore's QRT/SWAT

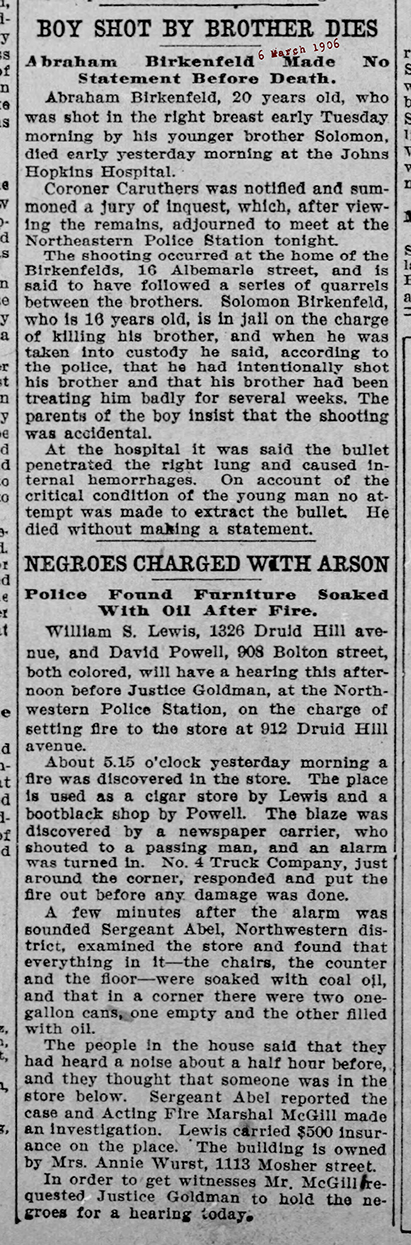

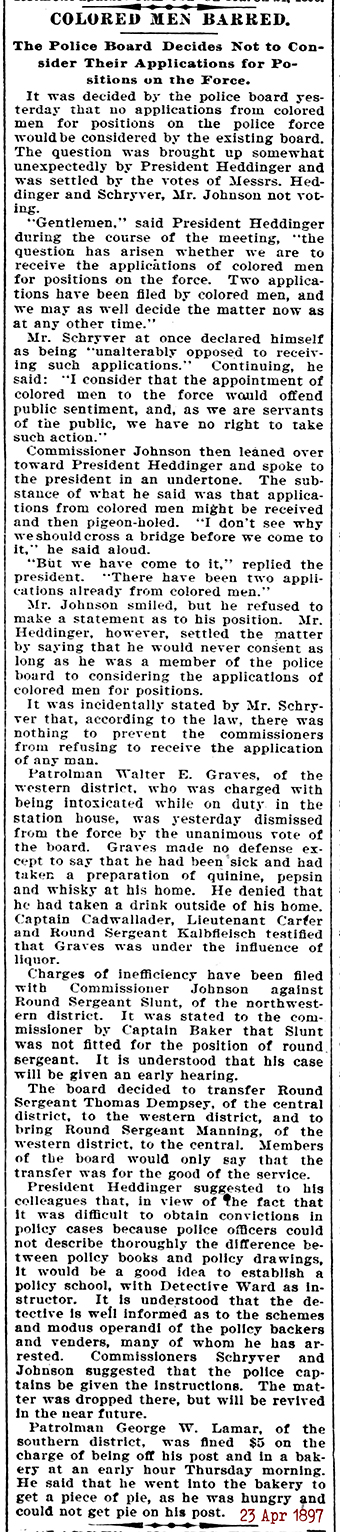

BPD Shame

BPD Shame

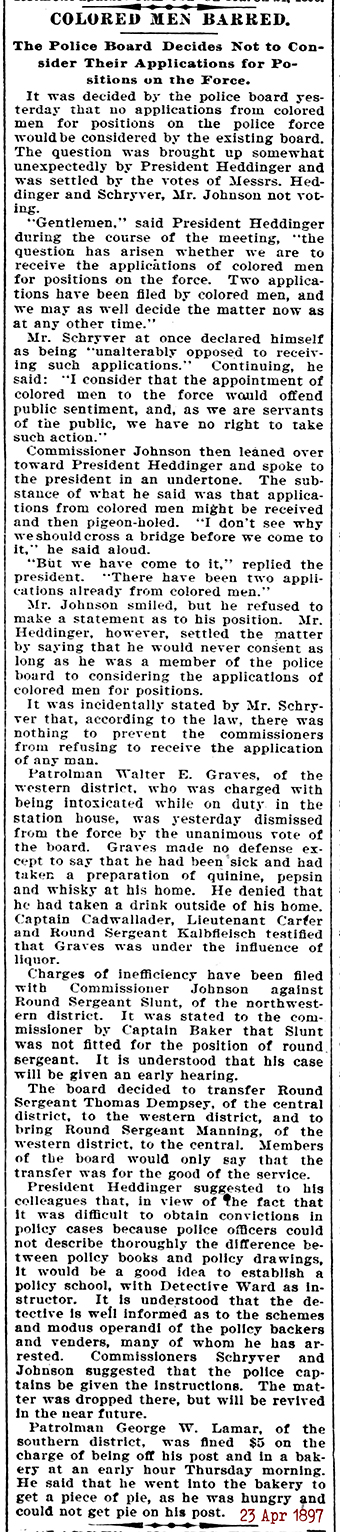

There are a lot of things within the Baltimore Police Department that make those of us that have served a a city patrolman quite proud. But, then, we find something like the following newspaper article, and we are completely embarrassed that our agency could have ever been like that. As embarrassed, as I can get, I find myself looking for signs that it is no longer the case, and that we have come a long way. I am thankful that in today's age we all work together, race wasn't an issue, when we got a call we went, when an officer was in need of help we went, no one ever asked the race of the officer needing help. We all ate together, played together, we had a brotherhood that made race something that was not an issue I spoke with some guys from back before black and white officers worked together, and then worked together, and they all describe it the same, and while it didn't start off good, it didn't take long for both men to realize the similarities, and while it frustrates me to see the ignorance of our agency in 1897, it is nice to know that it is all based on education, these men didn't know anything but what they read in the newspaper. We'll include the 23 April 1897 article and follow it up with more of the same, referring to quotes, with that I'll give you all a little clue, when we take a look at the Hall of Fame page, we might find a few more clues.

Quotes From The Past

Quotes From The Past

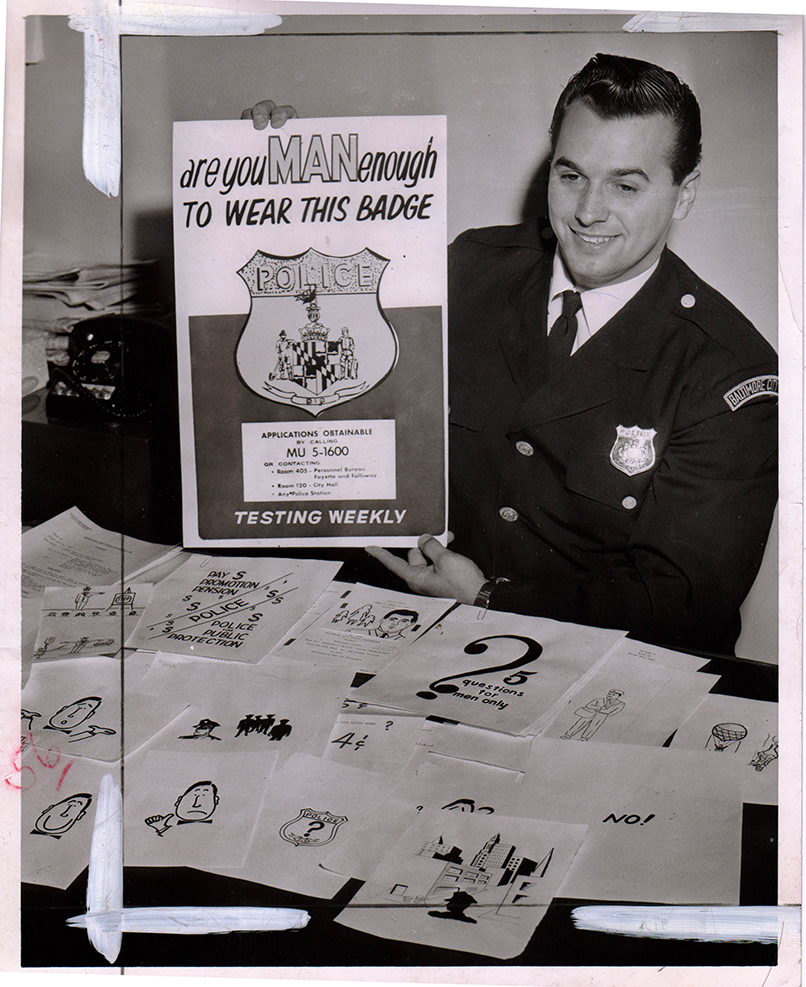

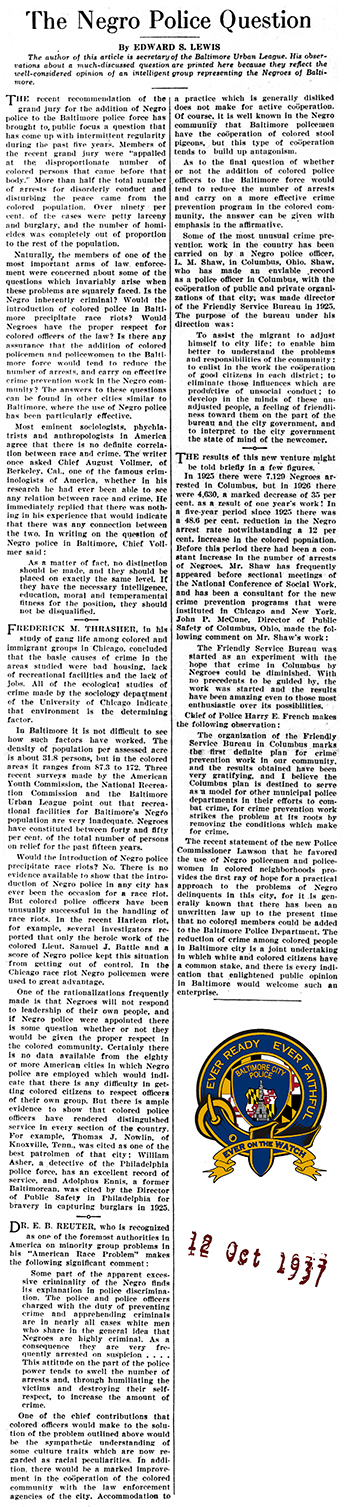

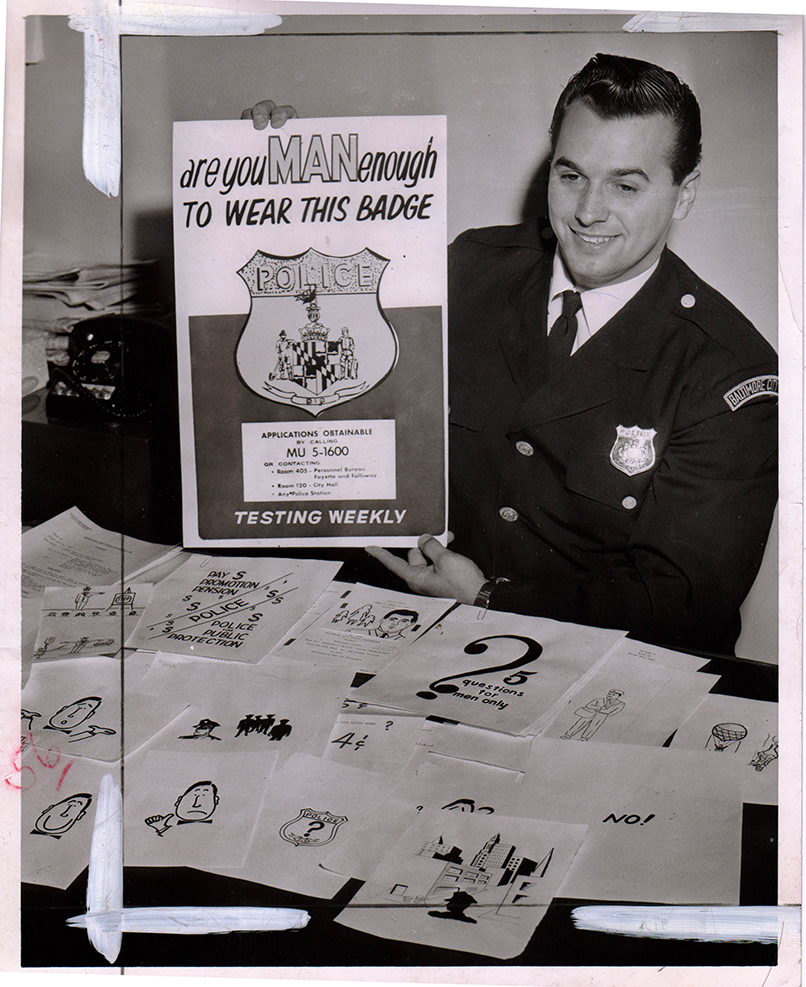

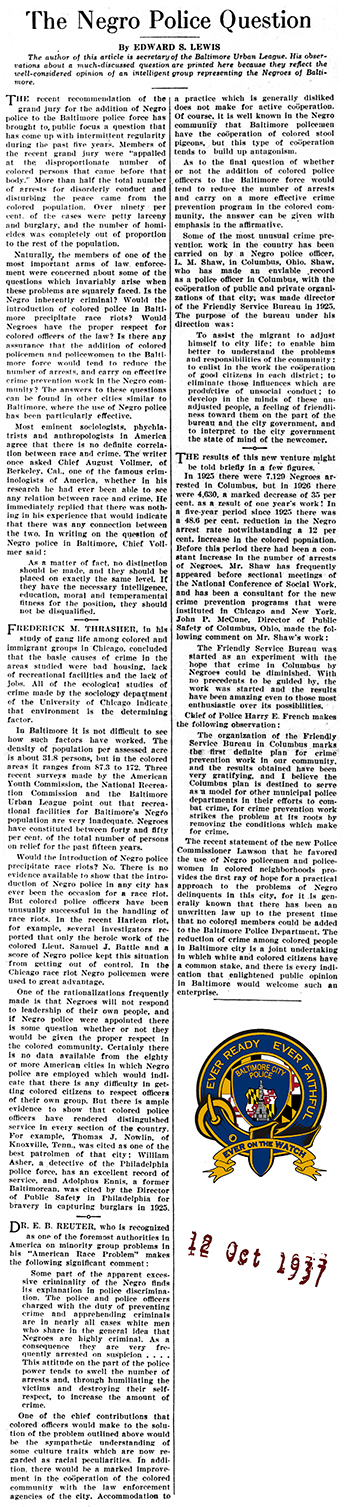

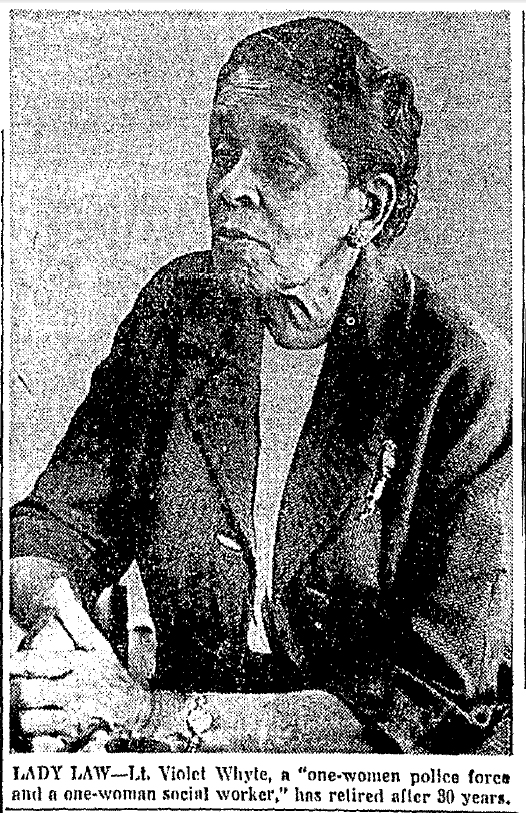

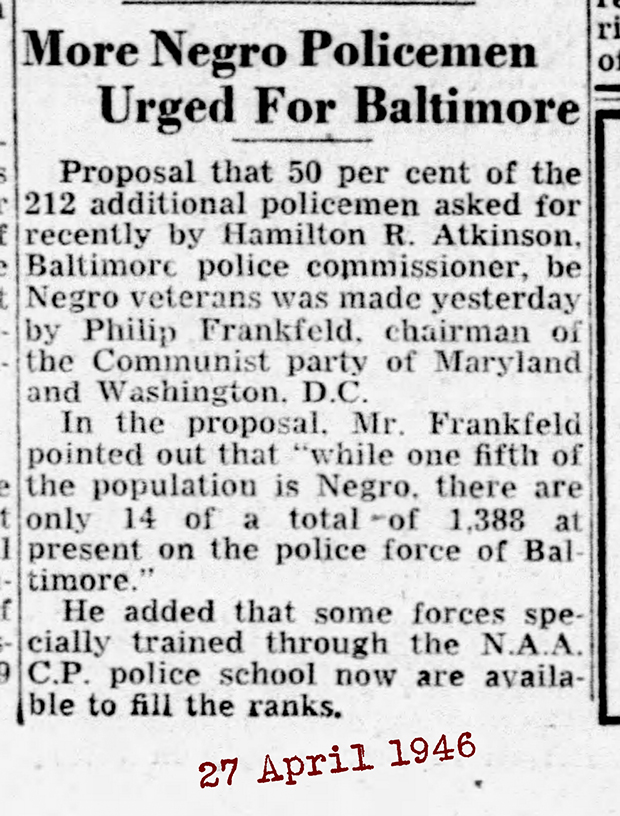

There is a lot of information and misinformation in the media and online. One thing we can do to get a better idea about the truth is to read newspaper articles from the time we are investigating, (and while the content was not always 100% accurate, there are several things we need to take into account that will always be accurate), 1st, dates aren’t wrong they are not subjective, when someone says "yesterday" and they are speaking/writing for instance on the 28 of Aug 1926, they are referring to the 27th of August 1926. It could be no other day because as we all know dates, and times are objective, and not subject to change. So, dates, and times are the same for everyone, and 2nd, choice of "language, comfort" use of certain words, or expressions become evidence of a different time. We will try to bring as many of those articles as we can, along with stories from those who worked during those times 50 to 100, or more years ago. The changes will be obvious, Race and Sex relations have changed dramatically over the years, from a refusal to hire women in 1909 and then when they finally did hire women police they had a different classification, they were, Policewomen and men were, Policemen. To the 1920s when they refused to hire African Americans. It was 1920 when a commissioner said he would not hire a "Negro" he went on to say, "The psychological time had not come" it would be 17 years, 1937 and a different Police Commissioner before they would hire African-Americans. And it wasn't just Race, and Sex, they also discriminated against Height, at one time (the date mentioned earlier, 27 August 1926) they increased the height and weight requirement of an officer by 3 inches, and 10 lbs, from 5'7" 140lbs, to 5'10" 150 - At the time they said, anything less than 5"10" 150lbs was less than, "The cream of the crop" as far as "manhood" was concerned, and lets not forget the 1950's - 1960's when they had recruit posters that said, "Are you Man enough?" Obviously gearing their hiring practices toward the Alfa male. With the following we hope to show the truth through articles that tell the story of difficult times, different times, and some terrific fighters, like Lieutenant Violet Whyte that worked for what the agency wanted, and changed history within the Baltimore Police department to take an already great department with some issues, and make it better.

Baltimore Police Recruit Poster

Baltimore Police Recruit Poster

Lt. Violet Hill Whyte

Lt. Violet Hill Whyte

The First African American Police Officer in the Baltimore Police Department was Officer, Violet Hill Whyte when she was hired on 3 Dec 1937. In an editorial, the Baltimore Sun said, "She worked in an all-white, mostly male-dominated institution, and won the respect of all those she worked with, she did it through hard work, and human understanding." The Sun report went on to say she explained her success by saying, "I'm not afraid of hard work." During her 30 years on the police force, she proved “hard work!” time and time again, she worked 16 to 20 hour days. Often she would begin her shift at 6 a.m. and not leave until midnight or 1 a.m. only to go home and go back to the station by 6 a.m. She worked cases, as well as collecting clothing for inmates, and the poor. She made holiday baskets for the needy and counseled delinquent kids and their families. She once said, "Being first at anything is hard because you represent so many others; if you do poorly, everyone will think all those you represent will also do poorly." I understand what she means, and how that can be hard, If I were voting for someone to become, County Council, and I heard one of the guys running was Irish, and a Retired Baltimore Police Officer, some might think he would automatically have my vote, but actually, I would want to make sure that if his nationality and former employment was a factor; before he got my vote, I knew he would represent us well, and that is Lieutenant Whyte was saying, if she had done poorly, it would reflect on all of her sex and all of her race and would have people saying, we must all be like that; so if we are all going to be judged on the acts, or conduct of one, then let us send the best we have. Let's not send the first that asked to go. Mrs. Whyte went in alone, she was notably the first African American Police Officer, and she represented well; 30 years, not one day missed; 30 years, she did more than she was asked, she worked doubles and more. She was an example not just for Women and African American Police, but for all police, it is sad that she is only remembered for being the first African American Officer on the Baltimore Police Department because she was so much more. Lieutenant Whyte was a good police officer, she was a hard-working police officer, a caring police officer… and she should be known for that… more than the color of her skin.

Sadly Lieutenant Violet Hill Whyte passed away on 17 July 1980 while in the Keswick nursing home where she had been since November 1979. - God bless her and thank her for her service. There is no use in being first if you can’t also be the best, and she was said to have been the best by any standard.

What Follows are the Many Articles that Tell the Story if Mrs. Lieutenant Whyte

First let's take a look at this Newspaper Article dated 3 July 1920, with a headline of - "No Negro Policemen, and General Gaither's Dictum"

Newspaper - 3 July 1920 - No Negro Policemen, General Gaither’s Dictum.

Subtitled; Announces none will be appointed, even if they pass the examination -

Declares time is not right - Representative of Colored Race Informed of Decision,

Can Maintain Order without them, Commissioner Rules.

Police Commissioner Charles D. Gaither has decided that Negroes although they take the examination, will not be appointed to the police force. General Gaither declared yesterday (2 July 1920) that "The psychological time had not come in Baltimore for the appointment of Negroes to the force." The Negro population was informed of General Gaither's stand through a Negro newspaper. Carl Murphy, the colored editor of the paper, called on General Gaither Tuesday and asked for the General's, "position on the subject of appointing colored men to the force providing they are successful in passing the examination, and their names were entered on the eligible list." The General told Murphy the time has not come for such action and that he positively would not appoint a colored man as a member of the Department. Murphy pointed out that New York City with the force of nearly 11,000 policemen at 8 Negro policeman. General Gaither replied that if the same percentage were applied to the local Department Baltimore would have no Negro policemen. There is no doubt, said General Gaither, "That colored policeman could be of value to the Department under certain conditions, but Baltimore does not need Negro policeman at this time. Our officers and patrolman have for many years maintained law and order in Negro neighborhoods and we propose to do so in the future. As far as I am concerned the question of appointment of Negroes to the police force is settled." Colored men interested in having Negroes appointed to the force made an appeal to the former police board headed by General Lawrason Riggs. At that time information was submitted showing that the following cities had negro policemen, Pittsburgh 65 Trenton 2, Philadelphia 300 Cincinnati 9, Chicago 95, New York 8, Los Angeles 18, Cleveland 15, Detroit 14, Indianapolis 13 Boston 25. Figures were also submitted showing the cities which did not employ colored policemen. The large southern cities not having negro policeman were New Orleans and Atlanta. General Riggs told the negro delegation then that he did not think the time had come for the appointment of Negroes to the force.

There were similar articles written in the Baltimore Sun 1909, Titled "Woman Cops?-- OH, My!" Subtitled "Police Officials Discuss Rev. Anna H. Shaw's Plan". it goes on to say, "Best Beat For a Woman, Takes Her All Over Her House", as they were rejecting the hiring of women on the force in 1909. In June, and July of 1912, Ms. Mary S. Harvey, and Margaret B. Eagleston became the first women hired by the Baltimore Police Department. So while there were issues over hiring Women, and over hiring African American Officers, it may come as a surprise that first African American Officer hired was a woman. General Gaither was Baltimore’s Police Commissioner from 1920 until 1937, on 4 December 1937, after Gaither's exit from the Baltimore Police Department, Mrs. Violet Whyte would become Baltimore Police Department's first Africa American Officer. She would eventually become assigned to the Northwest District, where she worked for 30 years, sometimes working 16 and even 20 hours a day. In 1955 she was promoted to the rank of Sergeant, and in 1967 several months before retirement, Sgt. Whyte was promoted to Lieutenant. She retired on 7 December 1967 but continued working for anywhere from several weeks, to several months depending on who you talk to, or what you read... But one thing they all say, she was a hard worker, she was determined and she had to finish a project or several projects that she had started.

African Americans in the department

African Americans in the department

More on Lieutenant Violet Whyte, by way of several Sun paper reports

POLICE WORK BEGUN BY COLORED WOMAN

Mrs. Whyte became the first Negro Member of Force, Assigned To Northwestern this information coming from a newspaper dated 4 Dec 1937 telling of Ms. Whyte's appointment her being appointed a day earlier on 3 Dec 1937. This was nearly 10 years before baseball's Jackie Robinson would hit the fields for the Brooklyn Dodgers on 15 April 1947 and 17 years before the Baltimore Orioles would hire pitcher Jehosie "Jay Heard on 24 April 1954. So while our Police department seemed behind in the times, they were really ahead of the times and would have been much quicker had it not been for Commissioner Charles D. Gaither. Once he was out of the way Commissioner William Lawson stepped up and hired Mrs. Whyte, allowing her to go on to do outstanding work for the Baltimore Police Department and the community she served.

Charles Gaither (NOT Pictured Here) our department's first solo Police Commissioner (prior to Gaither, we had a board of commissioners, that needed to agree on policy, hiring, uniform ad equipment changes. Charles Gaither had a variety of reasons for which he said he would refuse to hire African American Police Officers and while serving commissioner for 17 years he did some OK things, but the things he refused will be what he is best remembered for, and why our Baltimore Police Hall of Fame has Lt Kelly, and a page is being drawn up for Commissioner Lawson, but we will never see Commissioner Charles Gaither on the Hall of and page. He was Commissioner from 1920 until 1937 when William Lawson became Commissioner and before long things started to change for the better. As many of us know Lt. Whyte became our first African American Policewoman 1937 under Commissioner Lawson.

Qualifications For Post Are Cited By Commissioner Lawson

Mrs. Violet Whyte, Baltimore's first colored member of the Police Department, last night [3 Dec 1937] took over her duties as a policewoman, assigned for the moment to the Northwestern district. William P. Lawson, Commissioner of Police, in a statement outlining her qualifications for the post, said last night that after her work in Northwestern was finished she would be available for duty elsewhere in the city.

Appointee Lauded

Policewoman Whyte is "one of the best-prepared women among the colored people of Baltimore for the work she is to do," Commissioner Lawson said. He mentioned that she is the daughter of the late Rev. Daniel G. Hill, for many years pastor of Bethel AME (African Methodist Episcopal) Church. Lanvale Street and Druid Hill Avenue, and that among her brothers and sisters are a Vice-President of Howard University and an instructor at Lincoln University, an instructor at Princess Anne Academy, and another instructor in Southern College. Policewoman Whyte is 40, married and the mother of four children Her husband George Whyte, has been a principal in the public schools of Baltimore for the last ten years, she lives at 623 North Carlton Avenue.

Various Posts Named

Among the posts she has held or now holds, which fit her for her job, Commissioner Lawson named the following: Teacher in the School of Christian Education. Member, advisory board, Civic League. President, Intercity Child Study Association, Teacher, Department of Parent Education. Executive secretary, Parent-Teacher Federation, Policewoman Whyte is an active member of the Negro State Republican League.

Click the above pic or HERE to read actual article

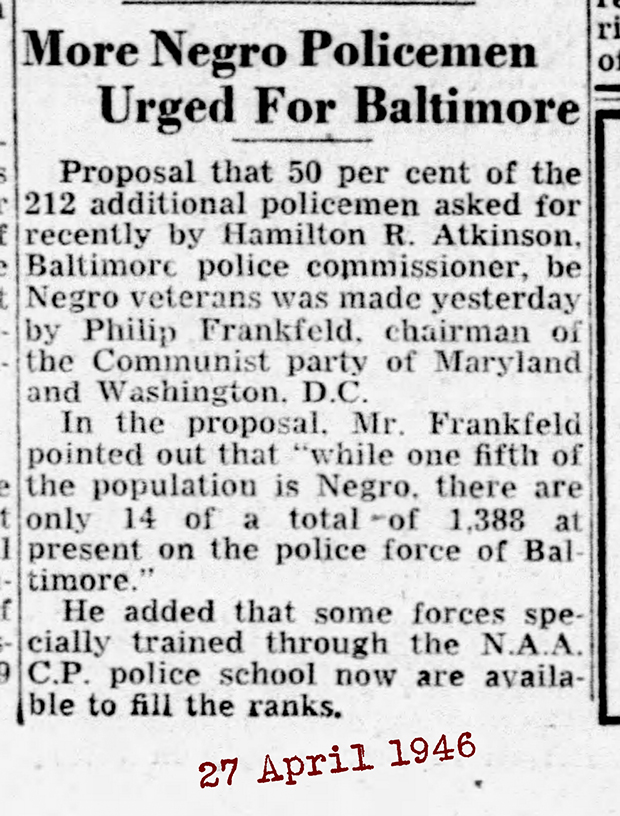

NEGRO POLICEMEN

10 July 1938

The appointment of four Negro, applicants to places on the police force might have created an uproar a generation ago. Today it is likely to be regarded as a more or less routine step following inevitably the growth of the city's colored population and the development among members of that race of individuals capable of discharging· the responsible work Which policemen are called upon to do.

It is perhaps unfortunate that such appointments have been urged by a Negro political organization and that they are made on the eve of an electoral campaign. What would otherwise have been regarded as an unobjectionable move toward racial justice may in the circumstances, take on a certain political color, and the results may suffer on this account. This is especially likely to occur on account or the Police Commissioner's close identification with a political party organization. In the circumstances, it might have been more prudent for Mr. Lawson to have waited until after the election to take this step rather than initiate it at the very start of a campaign.

But this point aside, there is little likelihood of difficulty as a result of these appointments, Baltimore has almost 150,000 Negro inhabitants. There is police work in the sections where they live for which officers of their own race ought to be peculiarity fitted. Provided the men now chosen for the four vacancies do their job well and carry their responsibilities as policemen should, they may look forward to as much consideration as other members of the police force received.

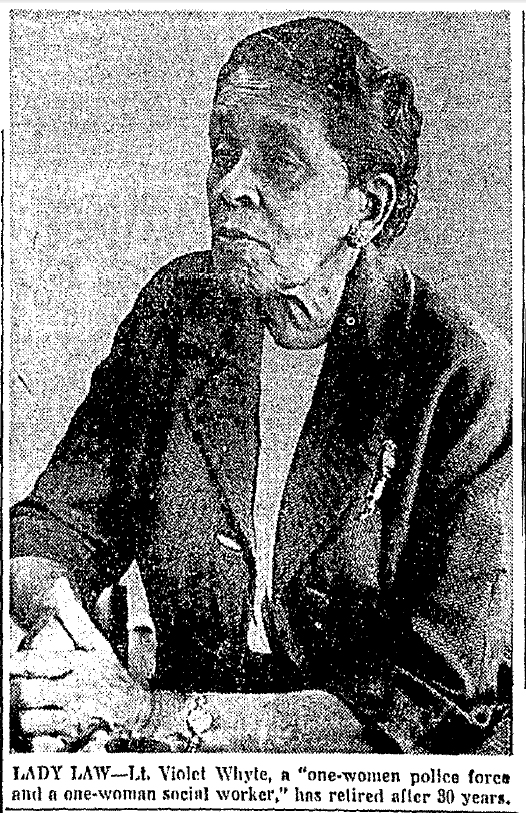

“Lady Law” Leaves The Force After 30 Years

“Lady Law” Leaves The Force After 30 Years

But Only Formally: as Volunteer She Still Helps All

7 December 1967

“Lady Law” as Lieutenant Violet Hill Whyte is known to hundreds of persons in West Baltimore, has formally retired from the Baltimore Police Department. But Lieutenant Whyte, the soft-spoken slender woman who made headlines as the first and Negro policewoman to join the force 30 years ago, (7 Dec 1967) still comes to her office at 6:00 A.M.) every morning. She organized the distribution of Thanksgiving baskets to needy families throughout the city and is now planning a Christmas party for 4000 children at the Royal Theater on Pennsylvania Avenue.

Holiday Project Goes

She councils as many as 125 persons a month who come from the city and county to see her and in addition, works a regular 8 hours a day as a member of the Western District force. Although she officially retired December 3, Lieutenant Whyte will continue those, and other activities on a volunteer base until the end of her “Holiday” projects. So she continues to collect Christmas toys in laundry baskets in the police station and to gather clothes for prisoners and their families. She is so awakened at all hours of the night by those who want, her help, or sometimes they call about the “Good News” she said, referring to a woman who phoned at 1:30 A.M. because she was, “so glad” about the birth of her first grandson. She would be described by retired Judge Charles E. Moylan Sr. of the supreme bench of Baltimore as a “one-woman-police-force, and a one-woman-social-worker combined” she has worked narcotics cases, homicides, assaults, sexual abuse, and robberies during her 30-year career.

She is Known for Bravery

Once she played the part of a “drunkard, cigarette smoking, dope addict” to help bring about the capture of a narcotics gang. For that, she received a Federal citation and was invited to appear before the Keauver committee investigating criminal rackets. Lieutenant Whyte, rarely carried a gun, in one incident she declined an escort as she went to help a 12 year-old-girl being held by an armed man. She said she enjoys testifying in court, and disliked child abuse cases more than any other assignments

I Get Emotionally Involved

“It’s with the children that I find I get emotionally involved,” she said “Emergencies always seem to happen before 6:00 AM” she said, adding she never needed a sleeping pill to go back to sleep when she was awakened, and never missed a day at work on account of illness, or otherwise. Lieutenant Whyte, the only Female Lieutenant of the 46 women on the police force, she was born in Washington and came to Baltimore as a young girl. Her father the Rev. Daniel G. Hill was a Methodist Minister (Bethel AME), and her mother a teacher.

Has Five Children

She graduated from Douglass High School and Coppin State College. She was married to a public school teacher, who went on to become a principal himself, and who is now dead. She has five grown children. “Retirement from one’s job doesn’t mean actual retirement,” she said. She is spoken in every State in the country and expects to continue her speaking career. She is also thinking of taking a job in the community service field. But after 30 years of work on countless crimes, and a lifetime of participating in church, and civic activities, she has one more wish – Time to grow flowers at her house on Elsinore Avenue. A testimonial fete will be held at 7:30 P.M. today in her honor at the Blue Crest North

To See Full Size Article Click HERE of on the Image Above

Whyte, Black Police Pioneer, Dies

Whyte, Black Police Pioneer, Dies

22 July 1980

Lieutenant Violet Whyte who in 1937 became the first black officer to be appointed to the city’s police force always said “I’m not afraid of work” The lieutenant who died last Thursday at the age of 82 proved during her 30 years on the police force, she meant what she said. Lieutenant Whyte often worked as many as 16 hours a day collecting clothing to the inmates and Thanksgiving baskets for the needy, and counseling to like what youngsters and their families in addition to handling cases that ranged from homicide to child abuse. The late juvenile court Judge Charles E Moylan Sr. once called her a “One-Woman-Police-Force and One-Woman-Social-Worker Combined!” Known as, “Lady Law” to her coworkers, the former police Lieutenant, and social activists never carried a gun. Born in Washington, she was the daughter of the Methodist minister, “My father taught me young, not to fear death, nothing has helped me as much in police work!” she said once, after helping the capture a narcotic gang, and impersonating a drunken, cigar smoking, dope addict on one of the most of the chilling of winter nights! For this action, she was invited to appear before, The Kefauver committee, which was investigating organized crime in 1952. She moved to Baltimore as a child and was a graduate of Douglass a senior high school, and Coppin State Teachers College. For about six years, she taught grammar school in Frederick County, then marrying the late George Sumner Whyte, a city school principal she stopped teaching, and raised four children. Two of them were adopted. In 1937 she became the first black police officer in the city of Baltimore and was assigned to the Northwestern District. In 1955 she was promoted to the rank of sergeant, she was in charge of the policewomen, and transferred to the newly opened Western District Because of the uniqueness of her occupation at the time she was asked to appear on The TV game show “To Tell the Truth” in 1962 and channel thirteen’s “The Brent Gunts Show”. In October 1967 just two months before retirement she was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant. She once told a reporter that of all the cases she ever worked to dislike child abuse of the most “It’s with the children that I find I get emotionally involved,” she said After retiring from the police force in December of 1967, she became a fieldwork supervisor for Planned Parenthood of Maryland and “continued visiting inmates and nursing homes with her sunshine bag of gifts and toiletries,” her daughter, Esther C Bailey, said yesterday “I belonged to everything in Baltimore!” Lieutenant Whyte one said when questioned about her numerous affiliations. She was appointed by both governors McKeldin, and Tawes to the board of managers of Boise and village in a Cheltenham. She was also on the Board of Directors of Provident hospital a board member for the former Maryland safety council, a member of the speakers bureau of the women’s Christian temperance union, a member of the Lambda Kappa Mu sorority, the Charmettes, a social group. The Phi Beta Sigma Wives, the F.E.W. Harper Elks Lodge No 429 and the Matinee Ensemble, a civic association The in addition to her daughter in Baltimore she is survived by two other daughters grace and Daniel of war Simpson and Grace Virginia of Waynesboro Pennsylvania, a sundial rustle of Eden Maryland three sisters Esther hill Isaiah and grace hill Jake up and Lea hill Fletcher all of Petersburg a Brother Joseph N hill of New York City and five grandchildren. Services for the lieutenant will be held at noon today at Bethel AME church 1300 sold 110. The family suggests that expressions of sympathy be in the form of memorial contributions to the acute stroke unit care of Dr. Elijah Sanders, provident hospital, 2600 Liberty Heights Avenue

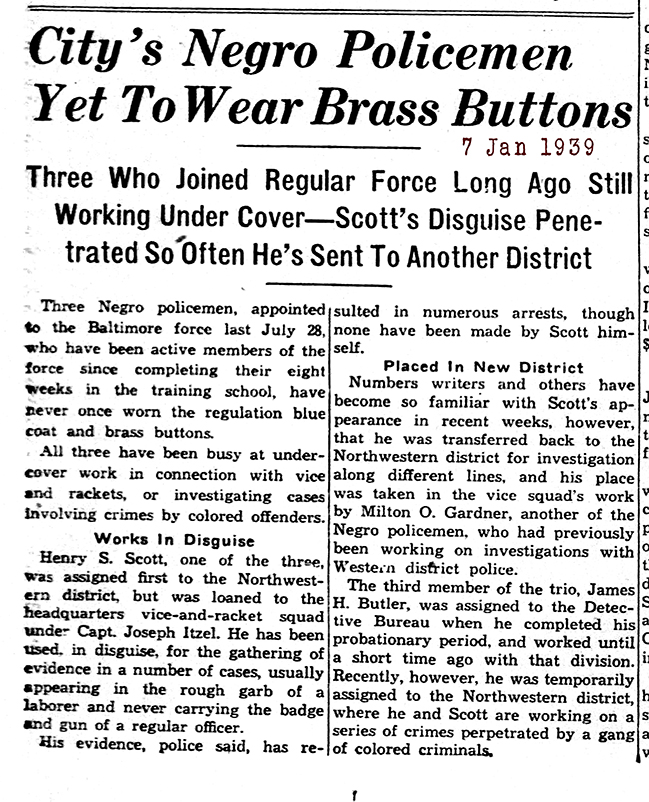

African Americans in the Department

A historically Irish American dominated police department, African Americans were not hired as police officers until 1937 when Violet Hill Whyte became the BPD's first African American officer. The first African American male officers Walter T. Eubanks Jr., Harry S. Scott, Milton Gardner, and J. Hiram Butler Jr. were hired in 1938, all of whom were assigned to plainclothes. In 1943, African American officers were finally allowed to wear police uniforms, and by 1950, there were fifty African American officers in the department. Patrolman Henry Smith Jr. became the first African American officer to die in the line of duty in 1962 when he was shot to death breaking up a dice game on North Milton Avenue in East Baltimore. The department itself had not fully integrated until 1966.

Prior to 1966, African American officers were limited to foot patrols as they were barred from the use of squad cars. These officers were quarantined in rank, barred from patrolling in White neighborhoods, and would often only be given specialty assignments in positions in the Narcotics Division or as undercover plainclothes officers. Further, African American officers were the target of racial harassment from their Caucasian coworkers and African American citizens in the communities they patrolled. During this time African American officers were subject to racial slurs from white co-workers during roll call and encountered degrading racial graffiti in the very districts/units they were assigned. During this time period, two future police commissioners of Baltimore, Bishop L. Robinson, and Edward J. Tilghman were amongst Baltimore's African American police officers.

During the civil rights movement, trust between the department and the larger African American city were strained. Racial riots due to police brutality were occurring all over America, and the racial mistreatment at the hands of several White officers labeled Baltimore as a trouble spot for violence. The police force at the time was also understudying for the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) as the department was severely troubled at the time. The IACP report showed the BPD to be the most corrupt and antiquated in the nation with an almost non-existent relationship with Baltimore's African American community. This lack of relationship resulted in African American citizens being subject to both excessive forces from police officers, and retaliation from community members for interacting with city police officers. The changes demanded in the report occurred almost overnight with the hiring of new police commissioner Donald Pomerleau. Pomerleau himself was a prior-service Marine who authored the IACP report committed to changing the department and improving relations with Baltimore's African American community.

After Pomerleau's hiring, the department made reforms to improve the relations with Baltimore's growing African American community, including ending the segregationist practices within the department. In 1968, racial rioting in response to the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. broke out across Baltimore's African American neighborhoods. A few African American officers held rank within the department during the riot the white-dominated police department found itself at odds against the African American community. In 1971, the Vanguard Justice Society was founded, an organization representing the rights and interests of the department's African American officers. Throughout the 1970s, more African Americans advanced in the department with Black officers holding the positions of district commanders and chief of patrol. In 1984, in a political move by Mayor Donald Schaefer to give the majority African American population more power in the city, Bishop L. Robinson was named as Baltimore's police commissioner. Robinson was the first African American police officer to command the department which was previously controlled by Irish American and Italian American police officers. Robinson was also the force's first Black officer to command the Eastern District and the Patrol Division. The department also redefined several of its racial policies in direct response to riots in Los Angeles and Miami as a means of avoiding similar racial tension in a city with a larger percentage of African American citizens.

Currently, the department is administered by Commissioner Anthony Batts and Deputy Commissioner of Patrol Garnell Green, both of whom are African American.

During Martin O'Malley's administration as mayor, the department had become 43% African American. While progress has been made to improve the department's relationship with Baltimore's now majority African American community, improvements are still being made to the department which for several years has been subject to criticism for its treatment of African American citizens. Police community relations have remained strained with the war on drugs that has plagued several African American neighborhoods in East and West Baltimore and coincidentally enough, many of the most despised officers in several of Baltimore's African American neighborhoods are also African American.

There is a street named for Mrs. Whyte, (Violet Hill White Way, Baltimore, MD 21201) it misspelled her name. Seeing as she was a hero that fought for what was right, and helped to pave the way for other African American Police; it might be good to work to have that street name corrected to spell her name Whyte, instead of White. 2nd African American Woman Chosen as Police Woman - Mrs. Carolyn M. Robinson is 5th of Race to be Named to Department The department's second African American Female Officer was hired on 29 September 1942. She was a graduate of Morgan University and a former superintendent of the Maryland Training School for colored girls. As a member of the Police Department, she will be assigned as an assistant to Mrs. Violet H. Whyte, the first Negro ever named to the Police Department in the Northwestern District. This information comes from the Sun paper 30 September 1942, an article titled “2D Negro Chosen for Police Woman - Mrs. Carolyn M. Robinson Is a Fifth Of Race to Be Named to Department” and written as follows - The second Negro policewoman named to the Baltimore Police Department assumed her duties in the Northwestern district yesterday 29 Sept 1942 immediately after being appointed, Police Commissioner Robert F. Stanton announced. She is Mrs. Carolyn M. Robinson, a graduate of Morgan College and former superintendent of the Maryland Training School for Colored Girls. As an assistant to Mrs. Violet H. Whyte, the first Negro ever named to the Police Department, Mrs. Robinson will work among delinquents in the Northwestern District.

Fifth Negro in Department

The appointment came following the announcement of the findings of the subcommittee on employment or the Governor's Commission which was asked to study problems affecting Maryland's Negro population. It recommended that greater participation should be given Negroes in community activities which affect their race. Mrs. Robinson is the fifth Negro to be admitted to the Police Department. Mrs. Whyte was appointed in 1923, and three Negro patrolmen were named a year later. They do plainclothes work exclusively.

Suggested for Uniformed Duty

A trial or uniformed Negro police for patrol duty in the congested Pennsylvania avenue region was suggested to Commissioner Stanton last Friday in the report of a special committee of the State Commission for the Study of Colored Problems

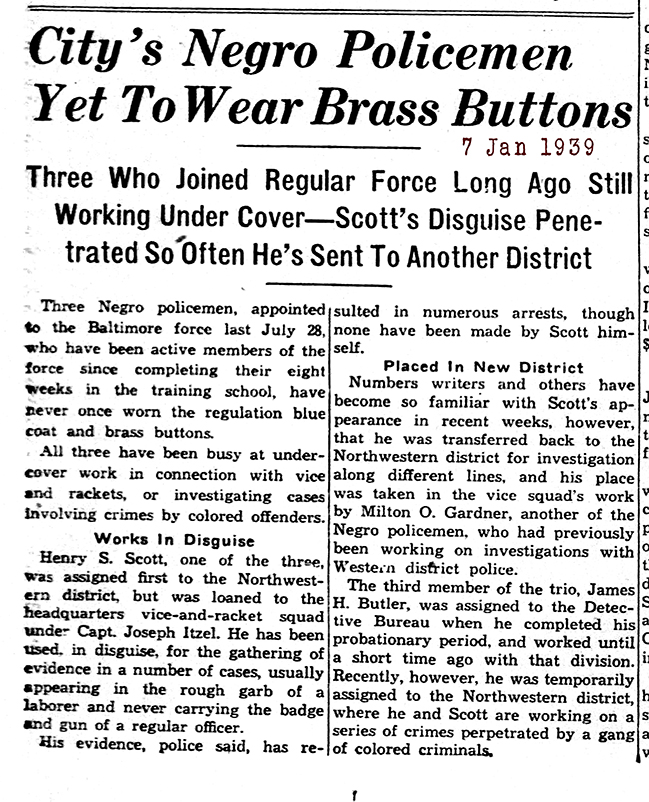

Milton O Gardner, Harry Scott, James H Butler

1938 - 28 July1938 - The first African American male officers hired were Walter T. Eubanks Jr., Harry S. Scott, Milton Gardner, and J. Hiram Butler Jr. were hired in all of whom were assigned to plainclothes - This pic is circa 1942-43 features Officers Milton O Gardner, Harry Scott, James Hiram Butler

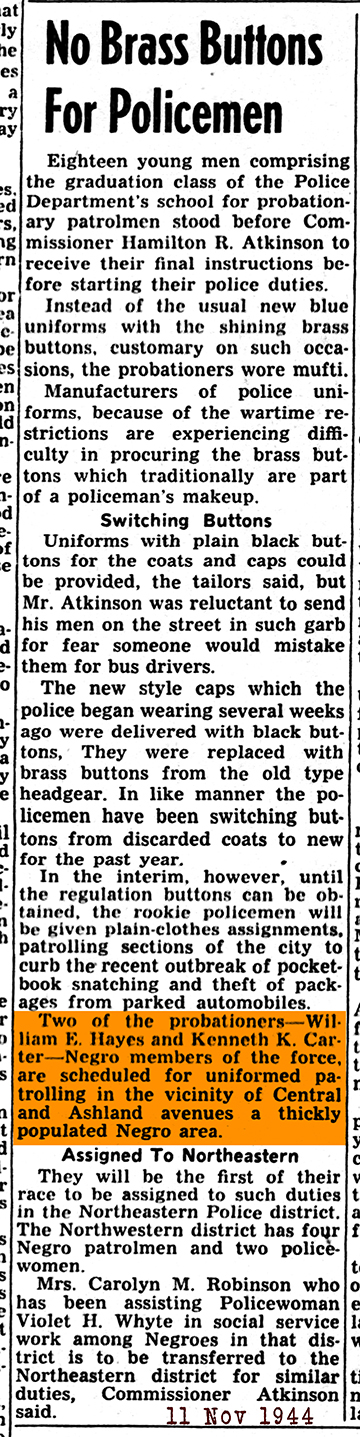

In November of 1944 when they hired Patrolmen, William E. Hayes and Kenneth K. Carter to work uniform on Baltimore's eastside, by this time things had already begun to change on the westside, but our agency had a long way to go, and a long way they have come.

In November of 1944 when they hired Patrolmen, William E. Hayes and Kenneth K. Carter to work uniform on Baltimore's eastside, by this time things had already begun to change on the westside, but our agency had a long way to go, and a long way they have come.

First African American Officers to work in uniform on Baltimore's Eastside

11 Nov 1944

1944 - November 1944 - Patrolmen, William E. Hayes and Kenneth K. Carter were the first African American Officers to work in uniform on Baltimore's eastside.

Photo and Info obtained from

Darryl Moore

The above photo was taken in 1964... Left to Right, Det Sgt. Clarence Roy, Det. Oliver Walker, Det. Elmer Moore, and Det. Lt. James Hiram Butler... The Photo was from the front page of the Afro-News American paper. It was referencing the Veney Brothers wanted for the murder of Sgt Jack L Cooper on 25 December 1964 at Greenmount Ave, in East Baltimore. Detectives were assembled from all units to become part of the largest manhunt in Baltimore City history to this day for the two suspects.

A Negro Captain

10 Oct 1965

Baltimore’s first Negro police captain, Dennis P. Mello, has attained his new rank and new position as head of the Western police district because he is a Negro. Rather than as an exercise in reverse racial discrimination, his promotion may be viewed as an enlightened community experiment, an effort to see if relations between police and citizens in the generally impoverished and deteriorating Western District can be improved by giving “the law" less of the appearance of resented white authority and more of the look of community understanding and concern.

Born into poverty and discrimination himself, Captain Mello is perhaps the ideal man to set the policing tone in a district where there is a critical need to engender an understanding of and respect for law enforcement. He knows the problems, and he knows from personal experience that there are ways out of the squalor and deprivation. He can be insistent and tough without being charged with racial misunderstanding and bias. But though he is going to have to be, because he is first and foremost a police officer, not a social worker, and his first and foremost duty will be to mount an unrelenting war on narcotics, assaults, burglaries, armed robbery, and street disorders. Crime is the community's enemy, irrespective of race; and Captain Mello’s police career will be judged primarily by how well he fights against it, irrespective of race.

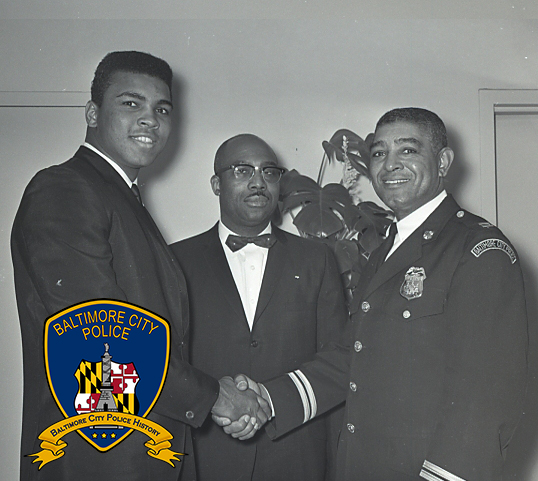

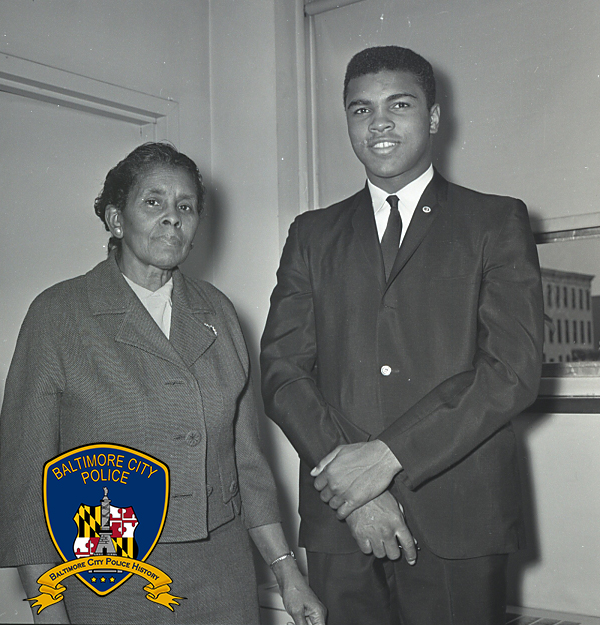

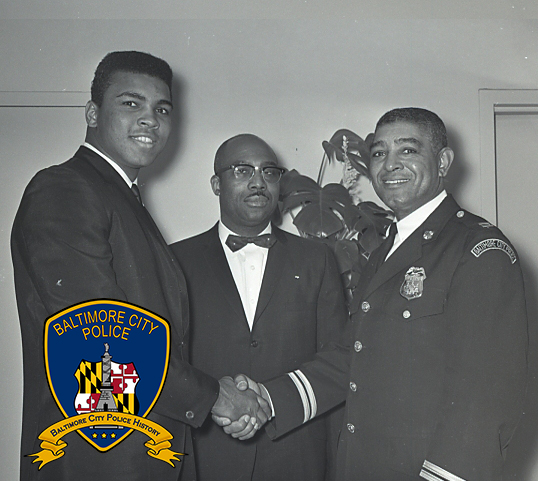

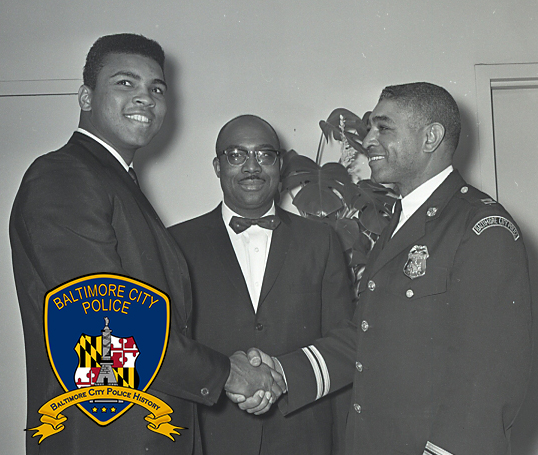

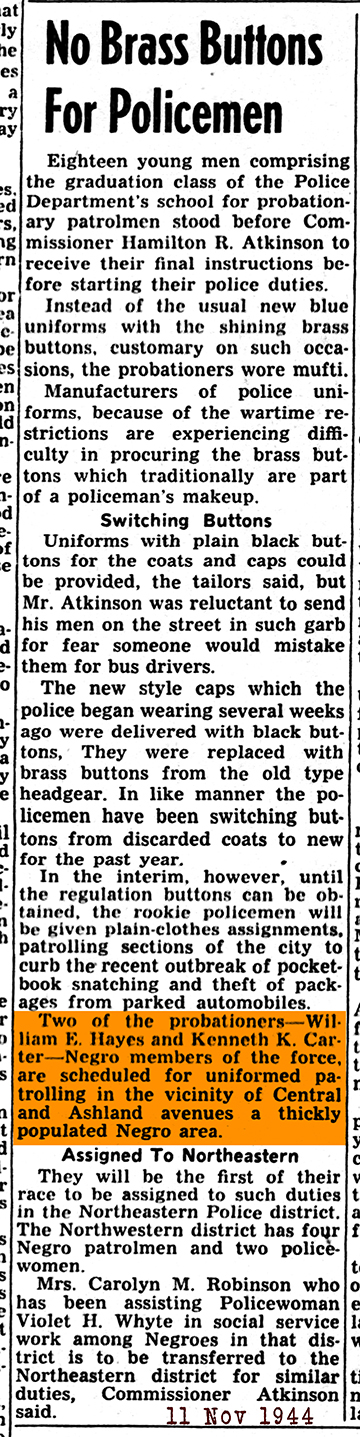

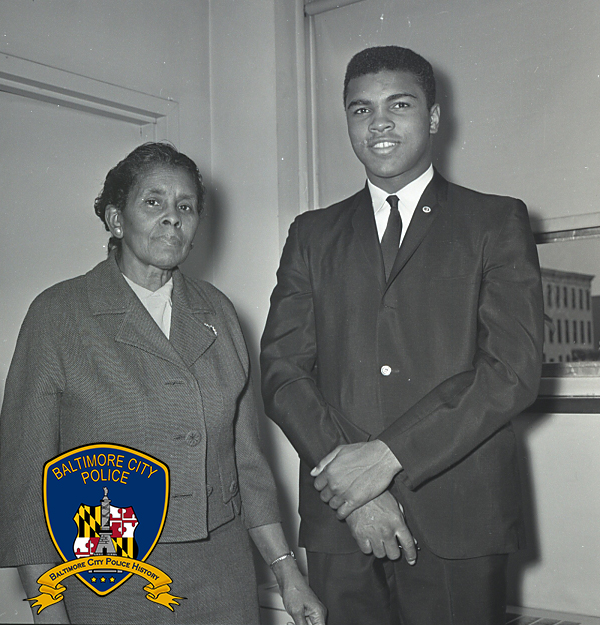

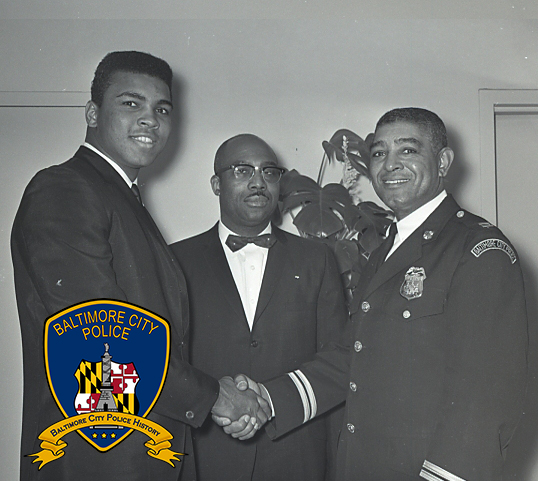

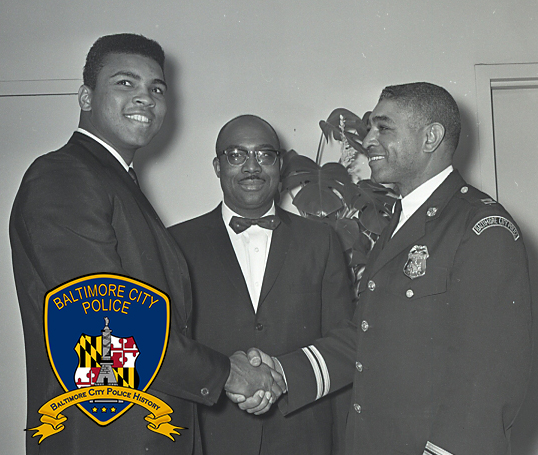

Muhammad Ali with Capt Mello and an unknown individual

Muhammad Ali with Capt Mello and an unknown individual

Dennis P. Mello, 84, Baltimore Police Captain

08 February 1997

As a Baltimore police officer, Dennis P. Mello never paid much attention to rank or color.

Being a black police captain meant nothing if the city was unsafe and its residents unhappy. That philosophy led other officers to refer to Mr. Mello, 84, who died Tuesday of cancer at his West Baltimore home, as a "policeman's policeman." "He was a good policeman who enjoyed doing good, effective police work," said Maj. Alvin Winkler, a longtime member of the city Police Department. "He cared a lot about others." Mr. Mello, who lived in the Ashburton section of West Baltimore, also broke several color barriers in his nearly three decades on the force before he retired in 1973: He was appointed in 1950 to work in the state's attorney's office, becoming the first black officer in the city courthouse. In 1957, he became the first black uniformed sergeant in the department's patrol division. He was the first black to reach the rank of captain and was given command of the Western District police station in 1965.

But being a "first" never fazed Mr. Mello, friends and relatives said.

"You'd never know he had moved up or been promoted because he took it all in stride," said Officer Donald "Chick" Matthews, a longtime friend and former colleague. "He'd act like, 'Well, it's a job.' He'd just keep on going in that gentle glide he had." An East Baltimore native and the fourth of 18 siblings, Mr. Mello graduated from Frederick Douglass High School in 1929 and attended Loyola College.

He joined the Police Department in 1944, becoming the department's sixth black officer.

"He had a deep inner sense of wanting to help people," said his grandson, Brian Peters of Baltimore. "He liked working with youths and encouraging them." Mr. Winkler, whose city police career began in 1968, said ranking officers were generally unapproachable by patrol officers during the period when Mr. Mello was promoted. But not Mr. Mello. "Captain Mello was an individual who liked to be around everyone," Mr. Winkler said. "He'd come out in the parking lot and talk to everyone, all of the officers. I remember he used to call everybody 'brother,' and it didn't matter if they were black, white or whatever." Mr. Mello's career wasn't without controversy. In 1973, he and several other Western District officers were indicted on federal charges of taking $50 a month in protection payoffs from gamblers. The ensuing trials dragged on for two years before Mr. Mello was found innocent by two federal court juries in 1974 and 1975.

He retired soon after the indictments.

"But I'm not mad at anybody," Mr. Mello said afterward. "Of course, it's a terrible thing to do to a person. I sit here and glorify the jury system. I've been in this for 30 years and it works, the judicial system works." Because of the rank he achieved, Mr. Mello was seen as a role model for young black officers. "All of the young black officers wanted to be like him and get to where he was," said Vernon Roberts, a former officer. "No one thought it was possible for blacks to get to captain until Captain Mello showed it could be done." L Mr. Mello married Belle DeShields in 1932. She died in 1988.

A Mass of Christian burial is scheduled for 10: 30 a.m. today at St. Francis Xavier Roman Catholic Church, 1501 E. Oliver St.

He is survived by a son, Earl Mello of Columbia; a daughter, Marlene Peters of Columbia; two brothers, Joseph Mello and Henry Mello, both of Baltimore; five sisters, Mary Coleman, Geneva Himan, Marian Forde, Corene Stokes and Gertrude Lewis, all of Baltimore; five grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren.

Pub Date: 2/08/97

Pioneering Black City Officer Dies at 91 Harry S. Scott Joined the Police Force in 1938

January 20, 1996

Harry S. Scott, who as the last surviving of the city Police Department's original group of black officers continued to inspire younger generations of black officers, died Monday at Northwest Medical Center of pneumonia. He was 91. Mr. Scott joined the city Police Department in 1938, and, like other black officers hired then and in the next few years, was not allowed to carry weapons or wear the departmental uniform. He retired in 1969 as a sergeant. Services with full police honors will be held at 11 a.m. today at Metropolitan United Methodist Church, Carrollton Avenue, and Lanvale Street. Bishop L. Robinson, who moved up from the officers' ranks to become the city's first black police commissioner in 1984 and then a top state law enforcement figure, remembered Sergeant Scott fondly yesterday. "I was just a kid about 10 years old," said Mr. Robinson, now director of the state Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services, "and I remember my father talking about Gardner, Butler, and Scott. We were living in the projects, and I used to go up to the Western District just to see him leave, wearing his uniform. He'd flash me a big smile. "He was an amazing man," Mr. Robinson said, noting that early in Mr. Scott's career, "he suffered the indignities of not being able to wear a uniform or ride in a squad car with a white officer, but he never complained. He used to say, 'We'll make it one of these days. The Lord will make a way.' "He built the bridges that we later crossed," Mr. Robinson said. In 1938, Gov. Harry W. Nice and several politicians in Catonsville, where Mr. Scott lived, urged him to take the police examination. At the time, Mr. Scott, who was a graduate of the old Baltimore Colored High School and had attended Hampton Institute in Virginia, was a yardman and coal deliveryman for Wilson Lumber & Coal Co. Mr. Scott, Walter T. Eubanks Jr., Milton Gardner, and J. Hiram Butler Jr. became members of the department together. Mr. Eubanks later dropped out but the other three officers joined Violet Hill Whyte as the first black officers in the department. A year earlier, Ms. Whyte had become the first black appointed to the city Police Department. The four officers' history-making achievements have become part of a permanent exhibit in the Police Headquarters museum on Fayette Street. Former city Police Commissioner Edward V. Woods said he was a young officer assigned to the Western District when he encountered Mr. Scott. "Knowing that he was the only black sergeant, you could look up to him," Mr. Woods said. "He was something to aspire to." Mr. Woods was the commissioner from 1989 to 1993 and now is retired. "In my time as a young black officer, you couldn't dream of becoming police commissioner. It just wasn't possible. But being a sergeant, that was possible because Mr. Scott had achieved that. He walked tall and had the respect of both black and whites, and he treated everyone fairly."When young black officers complained about being assigned to only black neighborhoods, he'd say, 'Calm down. You're a police officer and a representative of your race.' "He stood there as an example to all of us, and he passed on the baton to the younger generation who he knew would go farther than he did." Said Maj. Wendell M. France, commander of the city police homicide unit: "He challenged the system along with the others, and he made it possible for me to be here. Mr. Scott was always a gentleman who led by example, and we've tried to follow that example." Current Commissioner Thomas C. Frazier, who plans to attend today's services, said: "I admire both his ability and courage as a pioneer who changed the face of law enforcement despite the many obstacles and pressures that confronted him. He will forever be an important part of the Baltimore Police Department's proud history." Initially assigned in 1938 to the Northwestern District, where he was assigned to the vice squad and did undercover work dressed in mufti -- without a weapon. In 1943, Police Commissioner Hamilton R. Atkinson ordered black officers into uniform and declared that they were to be given regular beats. "We were celebrities because he was allowed to wear the uniform," said his son H. Stanley Scott Jr. of Baltimore. "People would come from miles around to see him in his uniform when he left the house. I was so proud of my father, and so were my mother, brothers, and sisters. The whole colored community was." Mr. Scott's assignments included the old Pine Street Station in West Baltimore and working with the Police Boys' Club from 1946 to 1952. He was promoted to sergeant in 1955. "He always advised me and my brothers to go into the post office because it was inside work," his son said with a chuckle. Mr. Scott was active in the affairs of the Metropolitan United Methodist Church. He also enjoyed fishing and helping Mack Lewis, the Baltimore fight promoter, train fighters in his gym. In 1927, he and Edith Smith were married. They lived for years in West Baltimore and later on Monastery Avenue. Mrs. Scott died in 1986. Survivors include three other sons, Theodore L. Scott and George E. Scott, both of Baltimore, and Leonard S. Scott of Bellevue, Wash.; two daughters, Edith A. Davis of Baltimore and Carolyn Bowser of Warner Robins, Ga.; a sister, Grace Lessane of Baltimore; 24 grandchildren; 12 great-grandchildren; and eight great-great-grandchildren.

Bishop L Robinson

Our first African American Police Commissioner

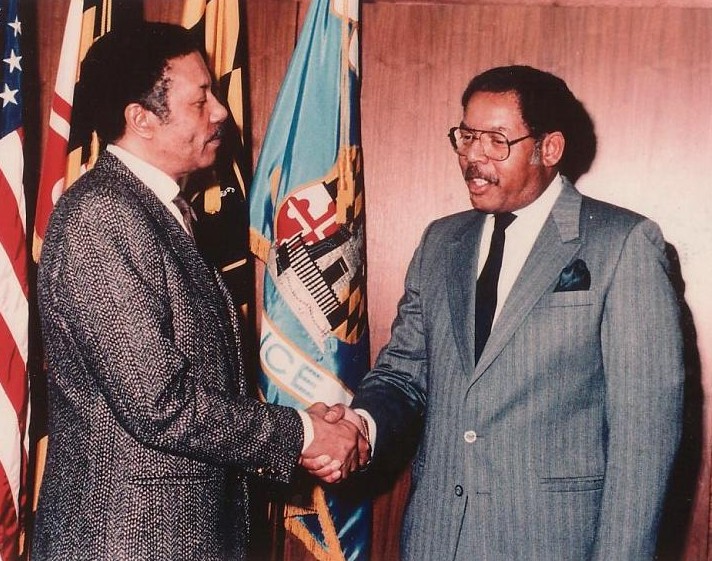

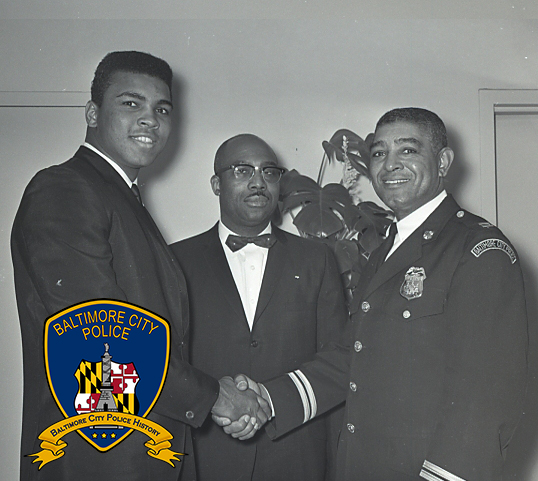

Bishop L. Robinson - Edward Tilghman

Bishop L. Robinson - Edward Tilghman

Bishop L. Robinson (born January 16, 1927), was the first African-American police commissioner of Baltimore, Maryland who was Commissioner of the Department between 1984 and 1987. A graduate of Douglass High School, Coppin State University and the University of Baltimore school of law, Robinson joined the department in 1952, earned the rank of sergeant in 1964, Lieutenant in 1969, Captain in 1971, Major in 1973, Lt. Colonel in 1974, Colonel in 1975, Deputy Commissioner of Operations in 1978 and Commissioner in 1984. Robinson also represented the Baltimore Police Department in the founding of NOBLE, a national organization of African American police officers from various American cities in 1976, and rose to the rank of a commissioner in 1984. For Robinson's first 14 years in the department until 1966, African American officers were quarantined in rank, not allowed to patrol in white neighborhoods, and barred from the use of squad cars during a time period where the Civil Rights Movement, Vietnam War, and Black Power movements took place. Robinson was elevated to the command of Commissioner in a department long dominated by Irish-American officers and briefly dominated by Italian American officers as a means of giving African-American officers control of the department as Baltimore City became solidly Majority African American. Following his service as Baltimore Police Commissioner, he served as Secretary of the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services from 1987 to 1997 in the Cabinet of Governors William Donald Schaefer and Parris Glendening, and subsequently as Secretary of the Maryland Department of Juvenile Justice in the Cabinet of Governor Parris Glendenning from 2000 to 2003. "What am I up to now? Not very much," says Bishop L. Robinson, 80, the city's first African-American police commissioner. "I spent 50 years in government and started my career with the Baltimore Park Police. I then moved on to the city Police Department and climbed every rank -- I didn't miss a step -- until Mayor William Donald Schaefer appointed me commissioner in 1984." When Schaefer was elected governor, Robinson followed him to Annapolis, where he served two terms as public safety director, and then one term during the administration of Gov. Parris N. Glendening. He was a state juvenile secretary when he retired in 2003. "I do a little consulting for Affiliated Computer Services. It's a national company that handles red light cameras, speed cameras, and E-ZPass," he says. "And I'm enjoying it. I get a chance to travel and meet people in other cities. And guess what? They're having many of the same problems as Baltimore. Some of them are even looking for police commissioners, but I tell them I'm not looking and I'm not in the market," Robinson says with a laugh. A big honor came his way this summer when the city's newly renovated police headquarters at East Fayette and President streets was renamed the Bishop L. Robinson Sr. Police Administration Building. "My wife, Ruthie Ann Robinson, and Oliver Walker, the oldest living Baltimore City African-American police officer who retired 36 years ago, spearheaded the effort to have the building named after me," he says. "Imagine a building with a cop's name on it. I drive by every day just to make sure that the sign with my name on it is still there," he says, laughing. Robinson and his wife enjoy traveling, they just returned from a trip to the Bahamas. Currently, they are keeping busy, raising a new dog -- Louie, a standard poodle -- and keeping Angelique, a Shih Tzu, from suffering fits of jealousy. "Actually, as far as my life is concerned, everything is going really well," Robinson says.

One of our first African American Police Officers

John Ellis "Bo" Blackwell

John Ellis "Bo" Blackwell

John Ellis "Bo" Blackwell, one of the first African-Americans to be appointed to the Baltimore Police Department, who overcame racism and enjoyed a 30-year career with the department, died Oct. 30 of respiratory failure at Sinai Hospital. The Ellicott City resident was 83. "John was a pioneering African-American officer and he kept us focused. We stand on his shoulders," said Edward V. Woods, who served as police commissioner from 1989 to 1993. "Thank God for people like John who always gave his all. We are a better community for it and the department is now a healthy and representative mixture of people," said Mr. Woods. "It is now representative of all the people, and in the old days, it wasn't that way." The eldest of five children, John Ellis Blackwell was born to Gladys Blackwell Gray in St. Michaels. He spent his early childhood on the Eastern Shore before moving to Baltimore, where he attended city public schools. In 1947, Mr. Blackwell, who had dropped out of school, joined the Marine Corps. He served for several years before taking a job at Bethlehem Steel Corp.'s Sparrows Point shipyard. While working at the shipyard, Mr. Blackwell and several friends decided on a whim to take the written examination for the Baltimore Police Department. Of that group, he was the only one selected to become an officer on Sept. 13, 1950. By 1950, there were only six black police officers on the force — the first three having been appointed in 1938 — who were kept in plainclothes for five years to "investigate Negro vice," reported The Baltimore Sun in a 1969 article. The article also observed that African-American officers weren't "particularly popular in their old neighborhoods." "We could only work in black communities and couldn't drive police cars. White people wouldn't let black officers arrest them, even though we had full police powers," recalled Mr. Woods. "We were excluded to one area of the city." But Mr. Blackwell and his fellow African-American officers soldiered on, working to prove themselves in order to get ahead while enduring station house jokes laced with racial overtones and racial epithets. Integrated patrol cars didn't arrive until the mid-1960s, and it took a picket line of black officers in 1963 at City Hall and police headquarters to integrate previously all-white units such as the crime lab and K-9 Corps. "I first met John in 1959, who was a patrolman in the Central District," recalled Mr. Woods. "In those early days, John helped keep me focused. He kept saying, 'You have a place here and you'll be a good law officer.' He gave me a certain stick-to-it-a-tiv-ness," said Mr. Woods. "He was an inspiration in those really very stressful times. He'd also say, 'Be proud of what you're doing.'" Mr. Blackwell later became an administrative assistant, Mr. Woods said, to Maj. Clarence Roy in the department's community relations division. He retired in 1980. "While serving as a police officer, he obtained his GED and received an associate's degree in 1971, graduating on the same exact day his daughter received her bachelor's degree in Washington from George Washington University," said a granddaughter, Candace N. White, a lawyer who lives in Manhattan, Kan. Mr. Woods said that he and Mr. Blackwell lived several blocks away from each other. "John and his family were like a second family to me. He was a great joy," he said. Mr. Blackwell had lived in Walbrook Junction, Pimlico and Pikesville before moving to Palm Coast, Fla., with his wife, the former Geraldine Cordelia "Gerri" Taylor, whom he married in 1949. In addition to being an all-around handyman who liked home improvement projects, Mr. Blackwell was an avid fisherman. He and his wife also enjoyed boating and for more than 30 years lived several months of the year aboard the Gerri-Jac, their 46-foot houseboat moored at the Baltimore Yacht Basin on Insulator Drive and at the Crescent Marina in Fells Point. Mr. Blackwell was a founder in 1975 and later served as commodore of the Dolphin Cruising Club, Baltimore's only black yacht club, which was part of the Federation of Black Boaters based in Jamaica, N.Y. In 1978, the couple was instrumental in the chartering of Flotilla 19 of the Coast Guard Auxiliary in Baltimore. He was the flotilla's first commander and attained Coast Guard Auxiliary retired status. Mr. Blackwell also liked to take cruises and traveled by steamship to Bermuda and the Caribbean. "Bo could sometimes seem quiet and reflective, but he was always up for a good time and enjoyed life with gusto," his granddaughter said. "He was never one to hold back an opinion and advice or turn down an offer of crabs and a cold beer." His wife of 54 years died in 2003, and in recent years, he lived with his daughter in Ellicott City. "He lived an amazing life. He was born of a young mother, raised in a rural community by his grandparents, and against all odds, became a public servant, earned a college degree, traveled all over the world and lived to know his great-grandchildren," said his daughter, Dr. Jacalyn Blackwell-White, a pediatrician. Mr. Blackwell was a member of Palm Coast United Methodist Church in Florida. He was also a member of St. John Baptist Church, 9055 Tamar Drive, Columbia, where services will be held at 2:30 p.m. Sunday. In addition to his daughter and granddaughter, Mr. Blackwell is survived by two brothers, Charles Gray and Joseph Gray, both of Baltimore; another granddaughter; and three great-grandchildren.

Black Policemen Win a Legal Point

Jun 17, 1984

The Baltimore City Police Department's 1982 written test for promotion to sergeant was unreliable and unfair to black: candidates, according to federal Judge Frank A. Kaufman, who ordered the city to create a new test and abolish the 1982 eligibility list. Judge Kaufman made his ruling on behalf of the Vanguard Justice Society, an organization of black city police officers, and ordered back pay, seniority and other benefits that have accrued since September 1983, for any member of the class-action suit who takes the new test, passes and is promoted. But he refused to order, as Vanguard has asked, that those blacks who failed the 1982 examination be reevaluated and promoted to sergeant if they are found qualified. That, he said, would amount to a "quota-type relief which this court will not grant in the context of this case."

Baltimore Police Honor Sergeant who Served Amid Segregation – Dixon Remembered as a Trailblazer for Blacks in the Police Force

James Dixon joined the Baltimore Police Department in 1954 as a black officer in an era of widespread racial prejudice. Police posts were segregated and blacks were not allowed in patrol cars. On Tuesday, a quarter-century after he retired as a sergeant, Dixon returned to the department for a ceremony to honor his service and thank him for his role in helping the department through a time of social change. Dixon, 77, was given a BPD hat and coffee mug. "I think today was really good for him because I don't think he realized how far the Police Department has come," said Derrick Dixon, James' son. "So for him to come out here and see a lot of Afro-American officers and commissioners, I think it blew his mind. "I think now he realizes a lot of the things he did for the Police Department and a lot of first-time things he did for blacks and realizes what it led to," Derrick Dixon said. The segregation in the police wasn't anything new for James Dixon, after his service in the military. He was one of the hundreds of Marines from Montford Point, an all-black boot camp in North Carolina, to receive a Congressional Gold Medal last month. "This was something I never expected, although the Tuskegee Airmen got theirs, so we shouldn't have been very far behind them," James Dixon said. "This is something I will cherish for the few days I have left in my life. But this is something I'm going to have framed and hung on the wall." Dixon served in the Marines from 1944 until 1946, but his placement there was itself a stroke of luck. Drafted by the Navy, Dixon was willing to go to prison rather than join a unit where he was forced to serve food or swab decks like other blacks who were in the Navy during that era. "I [said] that if I was put in the Navy, I was going AWOL because I wasn't going to serve any food or scrub any decks," Dixon said, teary-eyed. "Had I been put in the Navy, I would be in jail now. I'm not a servant." Much has changed since then, but the department has not forgotten Dixon's contributions, said Acting Commissioner Anthony E. Barksdale. "He's stood strong through all of it. And look at him. Still shining; still standing strong," said Barksdale. "He's giving me advice and telling me stories that are making me happy that I'm wearing the same uniform that he used to wear."

Equal Discipline Promised for Police Black, White Officers Treated Differently, Some Say

15 August 1996

Responding to complaints that black Baltimore police officers are treated more harshly than their white colleagues when charged with misconduct, the city's police chief is vowing to make changes to ensure "equal discipline for equal infractions." Last week, members of the City Council and several current and former black officers accused Commissioner Thomas C. Frazier of tolerating a double-standard in how black and white officers are disciplined. Yesterday, Mayor Kurt L. Schmoke agreed that the department has a problem and put Frazier on notice that he needs to do more -- and do it quickly. "It has not been dealt with as good as it should be," the mayor said. "But I am convinced that the commissioner is working on solutions so it will not be a problem in the future. I think there is a problem over there, but it's one that can be solved." In a 90-minute interview Tuesday, Frazier said he will cooperate with a City Hall probe into why black officers are far more likely than white members to be fired or severely disciplined, in many cases for committing similar offenses. "The key is that discrimination will not be tolerated in any form," Frazier said, responding for the first time to harsh criticism leveled at him at a council hearing last week. The commissioner said he already has instituted many reforms, including increasing the number of black officers who investigate misconduct and plans to do more to assure his department that discrimination is not acceptable. At the council hearing, several current and former officers -- some fired for misconduct -- testified that white officers facing similar charges were only reprimanded. The hearing was prompted by a report by former Officer Donald Reid, who found that of the 139 officers fired since 1985, 99 were black and 37 were white. Blacks make up 35 percent of the 3,100-member department. Reid's lengthy report circulated in the department before Frazier was hired in 1994. Three years ago, he wrote to then-Commissioner Edward V. Woods and complained that nothing was being done. Yesterday, Reid said that once again his complaints are being ignored. He charged that Frazier is taking credit for reforms instituted by his predecessor and said Frazier and Schmoke knew of the problems two years ago. Reid said a higher percentage of blacks has been fired under their administration than in the previous decade. Frazier "has simply not cared about the problem since day one," Reid said. "He had ample time to resolve the problem."

Capt. Dennis Mello and Lt. Violet Hill Whyte

Capt. Dennis Mello and Lt. Violet Hill Whyte

1937 - 3 December 1937 - African Americans were not hired as police officers until 1937 when Violet Hill Whyte became the BPD's first Female African American officer hired by the force.

1938 - 9 July 1938 - Four African American men have been appointed to the Baltimore Police Department William P. Lawson, Commissioner Police, announced yesterday.

1944 - November 1944 - Patrolmen, William E. Hayes and Kenneth K. Carter were the first African American Officers to work in uniform on Baltimore's eastside.

1947 - 27 January 1947 - Patrolman James H. Butler, Jr., who Saturday (25 Jan 1947) was promoted to sergeant, is the first African American to attain that rank in the Baltimore Police Department.

1965 - 8 Oct 1965 - Bernard J. Schmidt, the police commissioner, yesterday promoted Lt. Dennis P. Mello, 52, to captain, the first African American to attain that rank in the Baltimore Police Department

1965 - 10 Oct 1965 - Baltimore's first African American police captain, Dennis P. Mello, has attained his new rank and new position as head of the Western police district because he is a Negro. Rather than as an exercise in reverse racial discrimination, his promotion may be viewed as an enlightened community experiment...

1967 - 6 Oct 1967 - Despite efforts to recruit African Americans for the Baltimore police force, figures released yesterday by the Police Department show that only 6.8 percent of the force is African American.

1968 - 12 February 1968 - More than half of the discharged servicemen accepted into the Baltimore City Police Department in a three-week recruitment drive are African American, Major Lon F. Rowlett, department personnel director, said Saturday.

1968 - 13 March 1968 - Police departments across the nation are showing interest in the Baltimore Police Department's use of mobile vans to recruit African Americans, according to Ralph G. Murdy, deputy commissioner of administration.

1969 - 16 February 1969 - Black police: men in the middle - The African American policemen in Baltimore is the man in the middle. He is scorned by some in the black community as "Just another cop." He is looked down upon by some white officers as "Just another African American."

The story we promised earlier came from a white officer that came on in the mid 50's he gave this story and told it with passion, in his late 80's you could hear the hate in his voice as he told the beginning of his story, but as the story went on and he became more educated, we could hear the tone in his voice change, we could hear him go from hating someone he didn't know, to becoming a friend, to becoming a partner. When he realized everything he had heard and had been told over the years was wrong, he realized the mistake he had made, he and his partner both had these strong feeling of hatred for one another until they learned they were wrong. I'll put the story as it was told to me, and then we' ll put some follow-up information.

The story was told as Follows;

The story was told as Follows;

“When I joined, it wasn’t racist for the officers not to like other officers solely based on the color of our skin. The white police didn't like the black police, and the black police didn't like the white police. It was just the way it was, times were different, it may be hard for someone today to understand, but today we know there is no difference between a white man, and a black man other than the color of our skin. Back then the “N-word" was commonly used, I used it, my bosses used, we wrote it in (police) reports, it seemed like newspapers up until the ’70s referred to a black man as a "Negro," and a black woman as a "Negress." Martin Luther King referred to a black man as a Negro, so what I am saying is the word Negro wasn’t an issue, and back then the “N” word wasn’t an issue, or at least it wasn’t as obvious. Then we were segregated, and as such, we didn’t know better, it could be considered propaganda, education, or a lack of an honest education. But black men didn’t like us, and we didn’t like them.

I drove a milk truck before joining the police force and was at Whitelock St. near North Ave, it was in the am [still dark outside], and I turned the corner, you know there’s a little corner there near North Ave where there is this, blind spot. I was in a big milk truck when I took the turn, and I ended up hitting a guy. He popped up off the street and started saying, “I am OK… I’m OK," and "you can go, I’m OK” well, I wasn’t new to things like that and didn’t want to lose my job, so I went around to Pennsylvania Ave. Down by Gold St. I saw and flagged down a police officer, he was with another officer, and I told them I hit a guy. I told them in detail, and I told them how the guy said, he was OK, and that told me I could go. I explained I wanted to make sure I told someone, and that I didn’t want to be accused or thought of having committed a hit and run. The officer said, “Was it an “N-word”?”, I didn’t know any better at the time, that is what we all said, so I agreed, saying, “Yes!” He then said, “Don’t worry about it; you can just go back to doing what you were doing!” So, I went back to my route, as I passed the corner of the accident, I saw the guy, you know the one I had hit. He was standing there with another officer, he pointed to my truck and said, I was the one that hit him, and that I had just kept going! The officer flagged me down and asked what happened. I told him, what happened, and that it was dark, he was dress in all dark. They could see he was wearing the same clothes, and that he was dark-skinned! I told the officer what happened and that I didn’t just leave, explaining that I went over to Pennsylvania Ave, near Gold St. where I saw, and told some officers about the accident. and what had happened. The guy wasn’t hurt, he was walking around fine, the officers assumed he was just trying to roll me, or the company I worked for Cloverland Milk company and they had more money than I did, and that at first when he claimed he was OK, and sent me on my way, someone must have told him, that he could get money for having been hit, so he stopped the first officer he could find. Back then, the police didn’t like being used in that way; times were different. Today, I know it was wrong, for them to have called him the “N-word," and for me not to have corrected them. But my knowing that didn’t come until years later after having joined the police department.

Driving the milk truck wasn’t a way to make a living, it didn’t pay well, and I was robbed several times; I figured if I was going to be in the tougher neighborhoods, I might as well have a badge on my chest and a gun on my side. So, an old army buddy and I went down to the police department and joined. We both went through the academy; I was assigned to the Northeastern. I forgot where he went. We talked every so often, but for the most part, we lost contact. A few years went by when by chance I ran into him down by Lexington Market. He had heard I was no longer married. He told me I should talk to Doris, and I said she’s married. He said, no, her and husband weren’t working out, he used to beat her, so they were separated. Well, I didn't waste any time. I contacted her as soon as I could find her. Doris and I dated before I went off to the Army, but she had moved on. I had also met someone; a nurse and was married. But the marriage didn’t work out, and since Doris' marriage didn’t work out either, I went and looked her up. That was forty-three years, four kids, eight stepchildren, twenty-one grandchildren, twenty-six great-grandchildren, five great-great-grandchildren, and here we are today, still together, and still, every bit as much in love.

But back to his leaving the academy; it was graduation day; he had learned just before the proceedings that he was assigned to the Northeastern District. After the ceremonies while still at the armory he was called aside by a Sergeant and told he wouldn’t be going to the Northeastern right away, and that he and a few of the others from his class would be detailed to the Northwestern District.

Well, I didn’t mind; back then, the Northeastern was called, "The Country Club," and I didn’t want that, I wanted to go where the action. So, I was glad to have been detailed to the Northwest District; I liked it. After a few months, I went to my Sergeant, (Back then we didn’t have Majors, we had Captains, and under the Captain was the Lieutenant, it was a chain of command, and you didn’t break that chain. So anyway, I liked the Northwestern, I had made friends, I liked the sector, and posts I worked. I was young, full of piss and vinegar and loved the action; so, I went to my Sergeant and asked if I could stay; if I could make the detail permanent. The Sergeant asked, “Are you sure?” and I told him, I was positive, and that I wanted to stay. So, the Sergeant went in and talked to the Administrative Lieutenant. In those days we had four Lieutenants in the district, one for each of the three shifts (Shift Lieutenants), and one Administrative Lieutenant called an Admin Lieutenant that oversaw everything to do with the administrative work within the district – He took care of transfers. The Admin Lieutenant called me into his office, where he asked me if it was true, that I wanted to stay. I told him it was! He then asked, “Why would you want to stay here?” I explained that I worked in the area before joining the force, (so I knew the streets) I liked the guys I was working with, I enjoyed the action, and that, I wanted to stay. He said, he wouldn’t ask twice, and that he would take care of the paperwork. That was the last I heard of it, a few months later it was official, I was transferred to the Northwestern District.

Before Desegregation

It was before desegregation, and while we had black officers in the department, they didn’t drive the patrol cars, they couldn’t work certain areas, they hated us, and we hated them. I remember when the department desegregated, it was 1966 and didn't matter if you were a white officer, or a black officer; you were not happy about the impending desegregation. I mean, we all had regular partners, guys we worked with, we knew, and we trusted, Our partners were guys we knew had our backs, and we didn’t know the black officers, we didn’t know if they would fight when we needed someone on our side in a fight, and back then there were a lot of fights. So, my Sergeant pulled me aside, and told me, “If this "N-word" goes to sleep, I want you to call me; I want to you tell me so I can come out here, catch him, and then, I can fire his black ass. and can put an end to this bull shit!” I said, “Yes sir!” and I tried, I really tried, I am ashamed to say it but, I was ready to turn him in. I didn’t know him; all I knew was what I had heard. About halfway through the shift, (we were working a midnight) so it was around 3 to 4 am, it would have been time to hit the hole, (Back then when we were going to go to sleep, we called it, “Hitting the hole”!) because we generally found a hole big enough to park our car or hide from public view. But I didn’t know the guy, so I just kept driving around. Finally, he asked me, “Do you boys hit the hole?” I said, “Hit the hole? I’m sorry, I don’t know what you mean!” (of course, I did, but I couldn’t have him knowing that!). So, he said, “Yeah, the hole, you know, someplace private out of the way where we can go to get some sleep!” I said, “No, but if that’s what you want to do, just tell me where to go!” He directed me as to where I needed to take him, and before long, I had pulled up under a bridge/underpass, but he wouldn’t go to sleep. I was hoping he would so I could turn him in and get my regular partner back. But we just sat there staring up at the bottom of the bridge/underpass. Finally, I had to go to one of the bars to help them close the place. While I was inside, I looked out the door, and there he was knocked-out, fast asleep in the passenger seat of our radio car. So I called it in, and my Sergeant came out, but, as he drove by the radio car, my new partner was wide awake, the Sergeant just kept driving right on by; to this day I often wonder if he faked sleeping to see what I would do. But it doesn’t matter, because, by the end of the first week, we had started talking more, and by the second week I learned about his wife, kids, and life/ He had a wife and kids, I had a wife and kids. He told me his wife worked at a makeup counter downtown; my wife worked a Jewelry counter also downtown. Other than skin color, where we lived, grew up, and went to school, we had a lot of similarities. We had both grown up learning about each other, through propaganda that was meant to keep us apart. Other than our skin color, we were the same. But through a controlled education, of misleading information, that we had received from the media, schools, our families, peers, and communities, we ended up having prejudices. One night we got into a fight arresting a black guy that was resisting with everything he had, and I didn’t know if my new partner would help, but he was right in there, he struggled alongside me to subdue the suspect as well, or as hard any partner I had ever had before or since. By the end of the first month, we had become partners; moreover, we were fast becoming friends. And, there was no way in this world, that I would have turned a friend in for sleeping. At first, I was sorry they integrated us, but by the end of the second week, I was becoming more and more interested in making it work. I wanted to continue working together, and he was an outstanding partner. Again, we have to remember this wasn’t the 1980s when you came on Kenny; it wasn't the early 2000's when you had to leave, it wasn't anything like it is today in 2009; it was 1966. I came on in the mid-1950s, times were different, the internet wasn’t around, television wasn’t even what it is today. We were not educated to know anything but what we were told, or what we read in the newspapers. And it wasn’t just us, the black officers of that time hated the white officers, too. They hated us to a point, that; and I didn’t find this out until years later, but, the night my Sergeant asked me to report him for sleeping, and my new partner asked me if I was going to go to "the hole" and my Sergeant told me to turn him in for sleeping.. His Sergeant told him to do the same thing to me. So basically, the white officer’s sergeants and the black officer’s sergeants hated each other so much for their differences, but they thought alike. Both came up with the same plan to have their officer turn in his new partner, so they could have him fired, and then we could return to the way it was. We have to understand this, just in case it isn’t clear, the white officers didn’t want to work with the black officers, but the black officers weren't exactly excited about working with the white officers either. What the black officers wanted was to be able to work any post, drive patrol cars, wear uniforms, etc. They wanted to do the job that they applied to do, and that they thought they were being hired to do. The white officers wanted to maintain things the way they had them, working with the partners they already knew and trusted. That was until about halfway through that first month of having had been integrated It might be interesting to know that neither officer in this car turned the other in, and as far as the officer that told us this knew, no one in his district took the bait, not one officer would set their new partner up to be caught sleeping on duty. BTW, we have read a lot of reports from those days, and it seems sleeping on duty would have only lead to termination if it was chronic, but the first one or two times would have led to discipline, but it would have taken multiple incidents of sleeping to have an officer terminated.

The department itself had not fully integrated until 1966. Before then, black officers were limited to foot patrol; they were prohibited from the use of patrol cars. These officers were limited in rank, banned from patrolling the white neighborhoods and would often only be given specialty assignments in positions within the narcotics division, or as undercover, plainclothes officers. They didn’t want to work with white police, but they did want to be treated as equals with access to the same opportunities, equipment, uniforms, and future in the department. They hated us, they didn’t trust us, and we were the same. That’s why I say it wasn’t racist unless they were racist too, and I don’t think that was the case, in fact, Kenny, I know that wasn't the case. I believe to be a racist; one has to have the information available, and ignore the facts so that, that person can justify, or continue to believe what they want to believe. It could also be described, as not wanting to ever become friends even after knowing, we are all the same. It has to be willful because for me, knowing what I know now; there is no way to hate someone based only on the color of their skin, any more than it would be understandable to hate someone because on the way they dress, comb their hair, the job they have or the car they drive.

Once we worked together, we got to know each other, we got to like each other, and we became friends. To this day, I have a picture of my partner hanging on the wall of my living room, [he pointed to the wall where a framed picture of his partner him and a few other officers hung] and a smaller pic in my wallet, [which he also took out to show his pride in having become so close to his partner and friend]. I went to his funeral, his kid’s graduations, and their weddings. We would have been friends earlier, but we didn’t know, and that wasn’t either of our faults, society, the media, our education, families, and the department kept us apart. It was in the rules, and when those were the rules, they didn’t come near us, and we didn’t go near them, they hated us, and we hated them. We were both misinformed about the other. I know I said it before, but as much as I hated the idea of integration at first, I worked about 10, or 11 years before integration, and nearly 20 years after; those 20 years were much better than the first 10 or 11. I made a lot of friends, both black and white, and I know we would have missed out on a lot, had we stayed segregated.