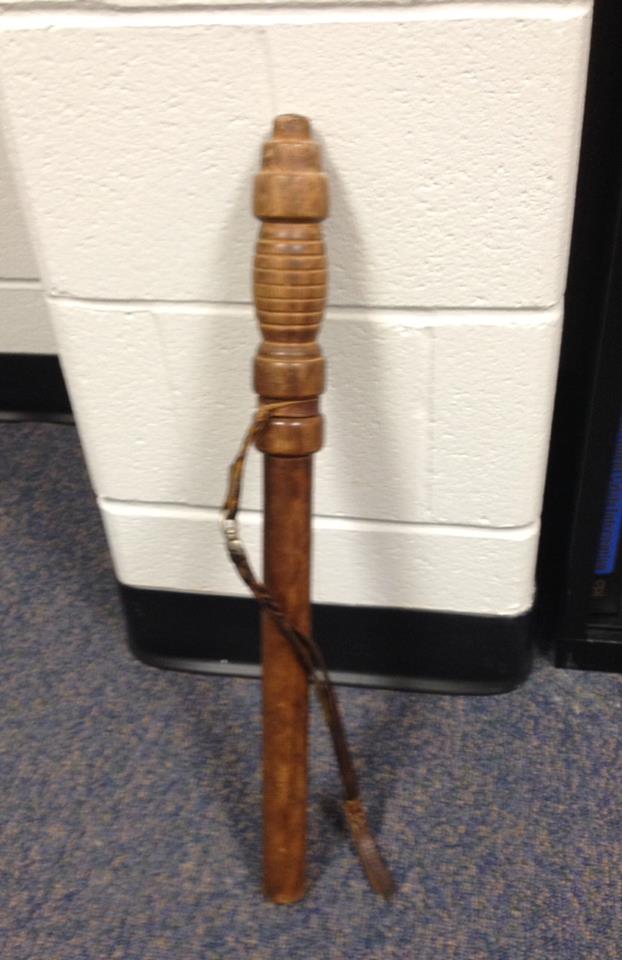

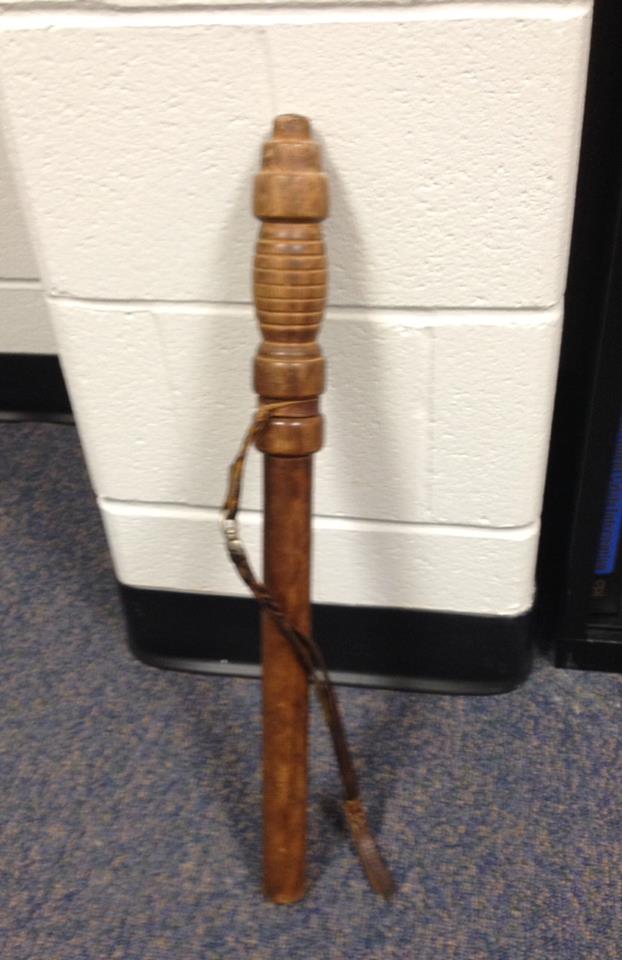

The "Barrel Head" often mistaken for the “Handle” and perhaps at one time may have been the handle, until guys like Carl Hagen, Edward Bremer, and Joseph “Nightstick Joe” Hlafka, put their spin on things. A "Swivel" was added (to aid in spinning the stick), Size was increased giving us what quickly became an acceptable “Oversize" stick. At some point the handle (Barrel Head) became the striking end, with “Nibs” “hardened/squared off edges for poking/jabbing, and "Size" for stopping power. Looking back we see Baltimore’s sticks quite possibly became the biggest sticks in Law Enforcement Thanks to guys like Nightstick our own Nightstick Joe.

Joseph "Nightstick Joe" Hlafka

The "Barrel Head" often mistaken for the “Handle” and perhaps at one time may have been the handle, until guys like Carl Hagen, Edward Bremer, and Joseph “Nightstick Joe” Hlafka, put their spin on things. A "Swivel" was added (to aid in spinning the stick), Size was increased giving us what quickly became an acceptable “Oversize" stick. At some point the handle (Barrel Head) became the striking end, with “Nibs” “hardened/squared off edges for poking/jabbing, and "Size" for stopping power. Looking back we see Baltimore’s sticks quite possibly became the biggest sticks in Law Enforcement Thanks to guys like Nightstick our own Nightstick Joe.

'Nightstick Joe': Guaranteed Hobby

John Kelly The Sun (1837-1987); Apr 11, 1983;

pg. D1 - `Nightstick Joe`: Guaranteed Hobby

Joe Hlafka gives a lifetime guarantee with every nightstick he sells. If you bash someone over the head with it and it breaks, he'll replace it free. That’s how sure he is of the quality of his work. Joe Hlafka – “Nightstick Joe” to dozens of his friends, and acquaintances – a squat, heavy–set, 45–year–old Baltimore City Policeman, who has turned a hobby; "woodworking", into a lucrative, part-time-business. Working in wood shavings up to his ankles in the basement of his South Baltimore row house, he turns out everything from nightsticks, to walking sticks, to children’s toys, and puzzles – all of which he sells at.. Well... bargain basement prices. He charges $20 (plus tax) for example, for one of his walking sticks. But he estimates it cost him almost $16 to make it – and that doesn’t include his labor. Similarly, he sells nightsticks that he says, cost him “about $10 or $12 to make” for $17 plus tax. Why? Because he’s not in it for the money. “It’s a hobby, something I do after work to unwind,” he says. “Some people like to go out and have a couple of beers. Me I like to come home and make things. That’s how I relax.” Besides, he thinks it’s amoral for anyone to make a huge profit. “My father always told me, if you serve the masses, you’ll eat with the classes.” I believe that, I try to concentrate on volume, and that way I’m able to keep my prices low, and still met a few dollars myself.” Most of Mr. Hlafka’s (it’s pronounced “lafka” as if the “H” was silent.) Nightsticks are sold by word-of-mouth to individual policeman, or to police supply houses – some as far away as Florida, and Texas. The nightsticks are heavier and sturdier than regulation nightsticks they weigh 12 ½ to 14 ounces and they cost about $10 more. But "they are superior to anything that is mass-produced, Mr. Hlafka says, and they meet all police standards.” They are made a Purple Heart, a durable, purple color wood grown in the South, or Bubinga, a strong West African wood similar to a Rosewood. For civilians, including the elderly, who want canes that also can be used for protection, there are custom-made “nightstick Joe” Hlafka walking sticks, longer and thicker than nightsticks, and much more elaborate. The handles our brass, usually in the shape of an animal head, and intricate diamond, spiral or fluted design carved with a router into the shafts. Both the walking sticks and nightsticks are soaked in linseed oil, dried and then sealed with the polyurethane to protect them for moisture, which is “the enemy of wood,” So, oddly enough, is rein – or the lack of it. “A poor rainy season can slow a trees growth and create weak spots in the wood, “Mr. Hlafka claims. He says the weak spots are not always noticeable, and the wood may break if it hit something hard. “I’ve tested the nightsticks with a hydraulic gauge, and can apply 110 pounds of pressure per square inch before the Purple Heart cracks. The Bubinga will take 210 pounds per square inch to break. “But if there are weak spots in the wood, the crack a lot faster. That’s why I guarantee my sticks. You never know when you might get one that’s bad.” Joe Hlafka was born and raised in South Baltimore, and has been a policeman for 13 years. He started in the Western district and transferred to the traffic division two years ago. His beat is a N. Charles Saratoga St. area, where he’s known for his affable good humor. One of his favorite ploys is to amble along the Street, “Hawking” parking tickets for drivers whose cars are parked in no parking zones – “a nice gesture,” according to one N. Charles St. merchant who says the policeman “makes his point without offending people.” According to the police department records, Mr. Hlafka has been shot six times in the line of duty. He was cited a few months ago for his part in foiling a robbery at the Charles center bank. He is married and credits his wife, a Della, with “holding the marriage together” for 25 years. “I’ve always been able to talk to her and discuss things,” he says, “and that helped me handle the stress of police work.” The couple has three daughters. A son Joe Junior, died a few years ago. Mr. Hlafka plays trombone in the Baltimore city Police Department dance band, sounds of an era, which performs for community groups, and he participates in a federally funded police program to get drunk drivers off the road. He began doing woodworking when he was nine or 10 years old.

“I join the police boys club and started making fancy lamps and things it’s something I’ve always enjoyed doing, but I never sold anything up until a couple years ago when I started making police nightsticks.” Since then he estimates, he’s made almost 500 nightsticks and another 200 walking sticks. He’s gotten inquiries from cities in France and England. He started making children’s toys a few months ago after he became “board” and making nightsticks. His first effort was a wooden pull train. It turned out to be an excellent choice. A little five – car train engine, coal tender, boxcar, tanker car and caboose are probably his most popular toy. Their guy will up by appreciative parents almost as fast as he can make them. Small wonder. He sells them for $25 – about half what comparable trains cost in most toy stores, Mr. Hlafka says. He also makes chunky little tugboats, blocky, old-fashioned cars models of the famous “black Maria” a police patrol wagon, and an assortment of simple wooden animal puzzles – squirrels, ducks, kittens – ranging in price from about 5 to 7 dollars “Every time I see something, I think, “I can do that,” its fun for me, I like the challenge to see if I can do it and maybe improve it. I’ve always believed the world is limited only by a person’s capacity to dream” Lately, Mr. Hlafka’s dreams seem to be getting bigger. He’s talking about building furniture. He says he got the idea after he saw a kit for grandfathers clock advertised in a magazine for hundred and $60 naturally, he thought the price was too high. “I can do it for a lot less than that” he said. For more information call 7?2 – 8??7 Joe retired from Turning his sticks in June of 2007

A look back through Nightstick History

Nightsticks have been in use since the caveman days, and on 19 March, 1798 we have the first mention of a Nightstick being used by the Baltimore Police Department. On 19 March, 1798 an officer known as “The City Constable” or “High Constable” was created by the ordinance of 19 March, 1798; it read in part, "His duty was to “walk through the streets, lanes and alleys of the city daily with MACE in hand, taking such rounds, that within a reasonable time…" We all know a "Mace" is a "Stick" a "Club" or "Weapon" a nightstick. So we know for sure Baltimore Police Officers carried a nightstick at least from 1798 until present day. In 1871 a newspaper article tells of an officer dying in the line of dury, and in it they say, his "Espantoon" was found under him where he lay on the ground. So we know the word Espantoon, goes back at least that far, and probably further, in fact we have another article dated 1843 mentioned the Espantoon, So the term goes pretty far back with Baltimore Police (We'll trace the term elsewhere on this page). Now looking back at photos from the 1800’s we see the sticks issued back then were similar in size and shape to the sticks we were issued in the mid to late 90’s when they stopped issuing sticks. Every so often we might see where an officer altered their stick, some shaved the barrel head so it was straight or concave instead of the convex “barrel shape” that gave it its name. Speaking of the Barrel head, it will take some additional research and study to see when we turned the sick around and started striking with the handle end, I know that became more popular after the late 50’s early 60’s when Carl Hagen came along and changed the shape of the standard Espantoon, Carl’s barrelhead was a little larger, but being rounded it wasn’t 100% obvious, he made and sold sticks into the 70’s when a man named Edward Bremer a retired house builder started turning sticks, he made sticks that without close examination might be confused for a Carl Hagen, except two things, 1 he used better tools so had a slightly cleaner cut, and second he liked to add what he called a “Nib” to the end so officer could poke a suspect in the stomach. Mr. Bremer, made sticks for police only, he didn’t sell to police supply houses, and wouldn’t make a stick for a citizens with the exception of a smaller purse sized club he would make for ladies to carrying their purse. Mr. Bremer made sticks until Joe Hlafka Came along in 1980/81 and Joe took the direction Carl Hagen and Edward Bremer were headed, and blew it up even bigger. Joe’s sticks were over the top big, he made a great stick that just about everyone I knew carried – Joe would go on to turn as many as 6000 nightsticks during his 26/27 years of turning nightsticks. And Joes Sticks were sold all over the world.

Espantoon History, Two years after the incorporation of the Baltimore Police Department in 1785 they appointed a police Chief and a high constable (then the Chief was known as a “Marshal”) at the time he toured the city caring a “Mace”, and it was known as his "Badge of Office". Oddly enough to this day our Espantoon is known as our “Badge of Authority”. In an 1843 the Sun paper report, a watchman had someone try to take his Espantoon by grabbing it during an arrest. From that report we know what it was called a "Mace" around the time we started carrying them in 1787, and that it was called an Espantoon some 56 years later in 1843. Now let’s look at the two terms... first a “Mace” often when we think of a Mace we think of a stick/club with some sort of axe blades, or a spiked ball on a chain attached to it… the Mace part of the spiked ball and chain or axe bladed weapon is actually the handle, the stick that the spiked ball, or axe blades attach to. Later the Mace is switched to Espantoon, which is exclusive to Baltimore Police, and derived from the “Spontoon”. A Spontoon, sometimes known by the variant spelling Espontoon (or as a Half-Pike), is a type of European "Pole-arm" that came into being alongside the "Pike". The Spontoon was in wide use by the mid 17th century, 1650-1675’sh, and it continued to be used until the mid to late 19th century 1860/1890’s.

Second Whirl for Espantoon

Tradition: After seeing proof in Webster's, the police commissioner approves return of the Baltimore nightstick.

September 23, 2000|By Peter Hermann | Peter Hermann, SUN STAFF

Nightstick Joe is back in business.

To the delight of tradition-minded Baltimore police officers, the city's new commissioner agreed yesterday to allow his troops to carry the once-banned Espantoon, a wooden nightstick with an ornately tooled handle and a long leather strap for twirling. Joseph Hlafka, who retired last year after three decades as an officer on the force and is best known by his nickname earned for turning out the sticks on his basement lathe, will once again see his handiwork being used by officers patrolling city streets. Orders for the $30 sticks are coming in. A local police supply store has ordered three dozen to boost its stock. Commissioner Edward T. Norris bought five. Young officers who have never seen one are calling with questions. "They want to know how to twirl it," Hlafka said. Before Norris arrived from New York in January, he had never heard of an "espantoon." He knew the generic "baton," "nightstick" and "Billy club," and was well acquainted with New York's technical "PR-24." He challenged his command staff to prove the term belongs solely to Mob-town. And there, in Webster's Third Edition: "Espantoon, Baltimore, a policeman's club." Norris signed the order yesterday, and the espantoon once again became a sanctioned, but optional, piece of police equipment. "When I found out what they meant to the rank and file, I said, `Bring them back,'" said Norris, who is trying to boost morale. "It is a tremendous part of the history of this Police Department." Hlafka is delighted. When the sticks were barred in 1994 by a commissioner who didn't like them, his production dropped from about 70 a month to 30, with most of them going to officers in departments across the country and collectors. They are now made from blocks of Bubinga, a hardwood imported from South Africa that doesn't get brittle in cold weather. Hlafka whittles and sands the wood to remove visible blemishes on the sticks, which measure from 22 inches to 25 inches long. It is art with a purpose. The espantoon recalls the bygone times of Baltimore law enforcement, when running afoul of an officer meant trouble. It fits in with the city's new assertive policing strategy of a new department leader who wants "police to be the police again." It is just what Hlafka, 62, wants to hear. "No one sold drugs on my post," he said while standing outside his William Street rowhouse, twirling an espantoon he had just finished. "They knew they would have to answer to me." Former Commissioner Thomas C. Frazier banned espantoons in 1994, saying that they weren't all the same length and weight and that an officer twirling the stick was too intimidating to the citizenry. In one order, the Californian uprooted decades of Baltimore police history. Espantoons - the word is derived from "spontoon," a weapon carried by members of a Roman legion - were first issued to nightshift officers before the age of radio communication. Officers used the sticks to bang on sidewalks or drainpipes to call for help. Twirling the stick became an art. "Telling a policeman not to swing his espantoon would be like asking a happy man not to whistle," The Sun said in a 1947 article. To replace the espantoons, Frazier issued long batons, called Koga sticks, which many officers refused to carry because they were cumbersome. It required hours of training in martial arts self-defense tactics, and some argued that the Koga stick was more dangerous than the espantoon. Sergeants were reluctant to send officers to Koga classes, and a trainer argued that some of the tactics being taught could be lethal on the street. Capt. Michael Andrew was among a handful of high-ranking officers who never took Koga training. He still has the espantoon his father gave him when he graduated from the police academy in 1973. His father, George Andrew, bought the espantoon from a West Baltimore Street shop when he joined the city force in 1940. The nightstick has been used ever since, "with the exception of five years when Frazier banned it, and we had to put it in mothballs," the younger Andrew said. In the old days, the espantoon was required equipment. "You better not have got caught without that stick under your arm," he said. "If you ever left it in your car, you'd get yelled at by your sergeant." The Andrews' espantoon started at the Eastern District, where his father began his career at the old stationhouse at East Fayette and North Caroline streets, and then moved with him to a foot patrol on Pennsylvania Avenue, in the Western. The nightstick is now in the hands of his son, and back on the city's east side. The 49-year-old captain addressed a group of younger officers assigned to flood the crime-troubled Eastern, and held up the espantoon as an invaluable tool for their jobs. He and other officers say that it can be used to stop threats without resorting to a gun. The elder Andrew, who retired as a lieutenant in 1974, recalled arresting a drunken blacksmith on East Fayette Street who had grabbed his legs. "I tapped him with the stick," the 86-year-old said. "He let go." Police commanders view the nightstick as an important tool that can be used to subdue people without killing them. "Mace is very effective, and it certainly has done its job," said Deputy Commissioner Bert Shirey, who still has the espantoon he was issued at the academy 34 years ago. "But there are times when Mace doesn't work, and it's nice to have something in between Mace and a gun." There is no doubt that getting hit with an espantoon hurts, and it can cause serious injury. Hlafka, who walked a beat at both the Inner Harbor and Lexington Market during his final years on the force, said he has struck many people with an espantoon over the course of his career. "People used to complain that we would hit them with the stick," Hlfaka said. "But would they rather get hit by a 9 mm bullet? Then, you don't come back."

Spontoon

A Spontoon, sometimes known by the variant spelling espantoon (or as a half-pike), is a type of European pole-arm that came into being alongside the pike. The spontoon was in wide use by the mid 17th century, and it continued to be used until the mid to late 19th century. Unlike the pike, which was an extremely long weapon (typically 14 or 15 feet), the spontoon measured only 6 or 7 feet in overall length. Generally, this weapon featured a more elaborate head than the typical pike. The head of a spontoon often had a pair of smaller blades on each side, giving the weapon the look of a military fork, or a trident. Italians might have been the first to use the spontoon, and, in its early days, the weapon was used for combat, before it became more of a symbolic item. After the musket replaced the pike as the primary weapon of the foot soldier, the spontoon remained in use as a signaling weapon. Non-commissioned officers carried the spontoon as a symbol of their rank and used it like a mace, in order to issue battlefield commands to their men. (Commissioned officers carried and commanded with swords, although some British Army officers used spontoons at the Battle of Culloden.) During the Napoleonic Wars, the spontoon was used by sergeants to defend the colors of a battalion or regiment from cavalry attack. The spontoon was one of few pole weapons that stayed in use long enough to make it into American history. As late as the 1890s, the spontoon could still be seen accompanying marching soldiers. Lewis and Clark brought spontoons on their expedition with the Corps of Discovery. The weapons came in handy as backup arms when the Corps traveled through areas populated by bears. There were also spontoon-style axes. These used the same shaped blades mounted on the side of the weapon, and had a shorter handle. Today, a spontoon (or espantoon, as it is referred to in the manual of arms) is carried by the drum major of the U.S. Army's Fife and Drum Corps, a ceremonial unit of the 3rd US Infantry Regiment (The Old Guard).

Espantoon

The Espantoon is a wooden police baton equipped with a long leather strap for twirling. It originated, and is still strongly associated, with the Baltimore Police Department in the city of Baltimore, Maryland. The term is considered distinctly Baltimorean. The word itself derives from that of a pole weapon, the Spontoon, which was carried by infantry officers of the British Army during the Revolutionary period. Since then the Espantoon has been considered a symbol of the "policeman's office and dignity". Before the advent of wireless communications, the Espantoon was reportedly used by Baltimore policemen to call for assistance where its user would bang it on the curb, cobblestone streets, or a downspout/drainpipe. Officers were often seen twirling their sticks, some called it twirling, others spinning and still others called it making the stick dance. This technique, of spinning the stick at the end of a strap of leather, had some other things about it that were unique to Baltimore; Baltimore officers were among the first officers to insert a swivel in the strap these swivels normally come from fishing lures, but have also been made from a keychain swivel, and would allow the stick to be spun continually for long periods of time. There were several reasons to spin a stick; it started with a need to communicate, officers had control of the stick and could bounce it off the ground/street to signal officers on adjoining posts. Other uses were to create distance, people could never enter the officers, "personal space" if he was spinning a stick in such a way that they could be hit by it if they were too close. There was yet another reason, a little less obvious, but served as a subtle reminder of the officer’s skills with said stick, making some think twice before confronting the officer. We have to remember that simply tucking the stick under the arm while talking to a suspect served as a deterrent on their part to want to lash out at an officer, add to this seeing an officer spin the stick around his back, across his side, and back and forth around his body, and one might think twice about challenging said officer. A good officer can spin a stick like a martial arts student spins nun-chucks, and few people want to go up against someone that has mastered a weapon of this type. In 1994, Thomas C. Frazier took over as Baltimore's police commissioner and banned the Espantoon. Frazier, a Californian, believed that the device, and the policemen's twirling of it, was intimidating to the civilian populace. He attempted to replace it with another weapon, the koga. Many officers, however, felt that the koga was cumbersome, difficult to master, and even more dangerous than the Espantoon. In 2000, Edward T. Norris assumed the office of police commissioner and lifted the ban on the Espantoon, although he did not mandate its use. The move was made as part of a general effort to boost morale and instill a more aggressive approach to policing in Baltimore. Norris stated, "When I found out what they meant to the rank and file, I said, 'Bring them back.' ... It is a tremendous part of the history of this Police Department."

Stick Nomenclature

1. The Leather Thong/Strap used to help retain the stick, also used to help officers spin the stick. Spinning the stick has multiple purposes, one it helps entertain them during long boring night shifts, but it also keep people out of their personal space, and some say, seeing how well the officer could spin the stick made them think twice about confronting the officer in a way that might force him to use his stick in self-defense. It demonstrated the officer ability to handle the stick.

2. The Handle end, most people think the stick is held at the other end, but the stick is actually held on the shaft end of the stick, with the Thong stretched out and looped around one or two fingers.

3. The Shaft, this is the long straight end opposite the Barrel Head, This also helps distinguish a Espantoon/Nightstick from other types of baton, as the shaft of a Espantoon is straight whereas Billy clubs it would taper out as it gets closer to the end.

4. The Ring Stop, this has two purposes, one it helps prevent the stick from going all the way through the nightstick ring/holder, it also serves as part of the Thong Groove/Slot helping to keep the Strap from moving up or down on the stick.

5. The Thong Groove Slot, this is where the leather thong/strap is woven onto the stick, to allow the officer a way of retaining the stick. It has also been used to spin the stick, for first aid, and to help pull people out of the harbor.

6. The Barrel Head, this end often mistaken for the nightstick's handle, is actually the striking end of the stick. When used to jab, or strike this can be more effective, taking less swings, with less force causing less injury. It also helps when using the stick for arm bars, and other holds as it gives a good grip that can be harder for a suspect to break free from.

By the way, in case you didn’t see else ware on this page/site, today we carry only nightsticks, in the 1700’s and up into the early 1900’s they carried different sticks at night then they did during the day. As a nightstick had more uses, signaling officers on different posts they used a longer stick at night, to not look as threatening during the day the officers carried a less obvious stick, it was the same in every way as the nighttime version except the shaft was about one ¼ to ½ its size shorter. These sticks, booth night and day version are not just used for striking, they are also used for jabbing, prying, applying pressure to pressure points; these methods can be quite effective, often more effective than striking. In the photo below you'll see a Daystick #11 with a Nightstick #10 and #12 next to it, showing the shaft in its different styles.

Espantoon

October 31, 2008

There has been great response to my postings and those of the Baltimore Sun's Copy Desk Chief John E. McIntyre on old police terms, clichés and the differences in cop lingo between Baltimore and New York. One reader reminded me of a New York term I had all but forgotten: "On the job." Several readers have commented on the Espantoon -- defined in Webster's Third Edition: "In Baltimore, a policeman's stick" -- and one asked for a picture of one. Here are a couple by Sun photographer Amy Davis shot back in 2000 when then Police Commissioner Edward T. Norris reversed a ban and allowed officers to once again carry the sticks. Tradition returned. Here is "Nightstick Joe" making an Espantoon in the basement of his Federal Hill row house in 2000, and another of him outside with the stick. What follows is the complete story published on Sept. 23, 2000 that I wrote on the return of the Espantoon. I've been warned against posting long takes from old stories, but so many want to know the history I think some of you might be interested: By Peter Hermann

Joseph "Nightstick Joe" Hlafka Espantoon

Joseph "Nightstick Joe" HlafkaEspantoon

We'll be putting together a great story on Nightstick Joe, his Nightsticks and how he could be part of the reason mpst police started using the word Nightstick instead of the word Espantoon, as used by older officers... After all he is known as "Nightstick Joe" not "Espantoon Joe" LOL - more to come

Police get Rid of an Old Weapon, Baton Training Aims to Supplant use of the Traditional Nightstick

August 11, 1996|By PETER HERMANN | PETER HERMANN,SUN STAFF

Bidding farewell to the fabled espantoon, Baltimore police are wielding a new nightstick on city streets and practicing new ways of confronting unruly citizens. The California-based Koga Institute is teaching officers procedures for searching, subduing and arresting people. They are based on martial arts, and the police chief hopes these techniques win minimize injuries to officers and citizens. Officers also are learning several maneuvers with the new stick -- called a baton -- which is replacing the espantoon, a nightstick used since the turn of the century. Although officers seem to like the training, the program got off to a rocky start. Some police commanders have been reluctant to change, and instructors privately have complained that some district sergeants and lieutenants have tried to steer officers away from becoming Koga trainers. Commissioner Thomas C. Frazier, over the institute's objections, decided to limit how officers use one baton maneuver -- a two-handed jab to the chest -- because he is concerned someone could be killed. Robert K. Koga, a former Los Angeles police officer, founded the institute in 1973. The self-defense techniques he teaches are based on Aikido, a combination of Greco-Roman wrestling and jujitsu. While the baton may be the most noticeable addition to the police force, officers are learning a wide range of Koga defense techniques. "The Koga Method is a , complete system, capable of providing an officer with an the tools needed to not only safely control a suspect, but control the officer as well," company brochures say. Frazier concluded more training was needed soon after he arrived in Baltimore in 1994 and spent several nights on the street, watching his officers make arrests. "What I saw frightened me," he said. Standard techniques were lacking, he said, putting suspects and officers in danger. Then there was the famed espantoon. Frazier thought the time-honored tradition of twirling the stick was intimidating to citizens, and he worried about injuries of people hit by the stick. "There was never any formal espantoon training," said Lt. Gerard G. DeManss, a 25-year veteran who heads the Koga training program in the department. "The department gave you something and didn't tell you how to use it." So far, 500 officers have been trained in the new techniques and given the new baton, which is 29 inches long and has no handle. The espantoon is shorter and thicker and has a grooved handle and strap. Instructors estimate it will take up to five years for all 3,100 department members to complete the program, which has cost the city $118,000 in the past two years.

This month, about two dozen police officers completed their last day of Koga training on the fifth floor of the old Signet Bank building on Guilford Avenue. Lining up on blue wrestling mats, they practiced how to arrest and search suspects, including having them lie face down on the ground to be handcuffed -- a departure from making suspects line up against a wall. The idea is to keep the suspect off balance, giving the officer leverage in case the prisoner tries to escape. The instructors emphasized the importance of technique. For example, when searching a suspect for a weapon, seven areas are checked, starting with the waistband, the most common hiding place. "If you start jumping around, you will miss something," Sgt. Ronald Fleming told the group. "You will miss the gun." The officers also went through a series of baton maneuvers, and instructors stressed that the blows are defensive. "It is not used as an offensive tool," DeManss said. Baltimore police do not teach two Koga maneuvers-a controversial choke hold that cuts off the blood supply to the brain and a practice of having officers approach suspects with guns in hand. DeManss teaches the controversial two-handed jab to the chest, but tells officers to use it only when they can justify deadly force. In other words, the jab is in the same category as the firearm. Koga argues that the jab can safely be used more liberally because it is not a deadly maneuver. But DeManss says "controlling force" manual is inconsistent with how is should be used. While it recommends against striking near the heart, diagrams clearly show officers striking a suspect's midsection. Making a distinction during a fight is next to impossible, DeManss said. The FBI "Defense Tactics Manual" lists "unacceptable target areas" for a baton, including any area near an internal organ, such as the cardiopulmonary and digestive systems. DeManss said Koga may be able to defend the jab in court, but he doesn't want to take the chance. "I can't find a doctor to sign off on this. It is taught [in Baltimore] as deadly force. Bob's totally against it. He said we just ruined the whole [program]." Adding to concerns, a law review article this spring by a University of Baltimore law student Brian L. DeLeonardo, warned that allowing officers wide latitude in using the jab would make the city vulnerable to civil liability. "A misclassification of a baton strike to the chest as nondeadly force provides ample ground for a jury to conclude that such a decision reflects a deliberate indifference to the citizens of Baltimore City," he wrote. After DeManss raised concerns, the commissioner agreed and ordered instructors to tell officers 'that this may be a fatal blow. You can't say go ahead and do a two-handed strike to the chest and not worry it can't be fatal, because it can." Maneuver defended But Koga strongly defends the baton strike. In a May 28 letter to Frazier, a copy of which was obtained by the Sun, he argues that in order to classify the blow as deadly force, it must be "likely to B] cause death.... In over 40 years of police work and police training, I have yet to hear of a fatality experienced due to blunt trauma to the chest by the baton." Koga also noted resistance 3 within the city Police Department to his program and criticized the way Baltimore is teaching it. "I have become aware that some students are afraid of retribution from some command staff who do not want this method,, which seems to be carried on through the lower supervisory ranks," he wrote. "It has been expressed to me that if an instructor voices positive comments in support of the program, they are essentially committing political suicide." Koga wrote that in some cases, lieutenants have "corrected" officers -- on the street who are using his techniques, reverting to the is old ways. "There appears to be no accountability to insure compliance with the policies of the commissioner's office," the letter says. DeManss said that "supervisors are avoiding this like the plague. Frazier is going to have to s3 put his foot down." Frazier said he not heard any complaints from the officers who have completed the program, but he acknowledged initial resistance. And he said there is a "lack of understanding on the part of the command staff," leading to some confusion on the street when ) sergeants and lieutenants see their officers handle suspects in what seem unusual ways. "It's different," Frazier said. "We're taking away the espantoon. The batons are longer and lighter and thinner. You can't spin them. All those are issues of tradition. It's just a process of change that we have to work through." Pub Date: 8/11/96

Nightstick Joe is Back in Business

To the delight of tradition-minded Baltimore police officers, the city's new commissioner agreed yesterday to allow his troops to carry the once-banned espantoon, a wooden nightstick with an ornately tooled handle and a long leather strap for twirling. Joseph Hlafka, who retired last year after three decades as an officer on the force and is best known by his nickname earned for turning out the sticks on his basement lathe, will once again see his handiwork being used by officers patrolling city streets. Orders for the $30 sticks are coming in. A local police supply store has ordered three dozen to boost its stock. Commissioner Edward T. Norris bought five. Young officers who have never seen one are calling with questions. "They want to know how to twirl it" Hlafka said. Before Norris arrived from New York in January, he had never heard of an "espantoon." He knew the generic "baton," "nightstick" and "billy club," and was well acquainted with New York's technical "PR-24." He challenged his command staff to prove the term belongs solely to Mobtown. And there, in Webster's Third Edition: "Espantoon, Baltimore, a policeman's club." Norris signed the order yesterday, and the espantoon once again became a sanctioned, but optional, piece of police equipment. "When I found out what they meant to the rank and file, I said, `Bring them back'" said Norris, who is trying to boost morale. "It is a tremendous part of the history of this Police Department." Hlafka is delighted. When the sticks were barred in 1994 by a commissioner who didn't like them, his production dropped from about 70 a month to 30, with most of them going to officers in departments across the country and collectors. They are now made from blocks of Bubinga, a hardwood imported from South Africa that doesn't get brittle in cold weather. Hlafka whittles and sands the wood to remove visible blemishes on the sticks, which measure from 22 inches to 25 inches long. It is art with a purpose. The espantoon recalls the bygone times of Baltimore law enforcement, when running afoul of an officer meant trouble. It fits in with the city's new assertive policing strategy of a new department leader who wants "police to be the police again" It is just what Hlafka, 62, wants to hear. "No one sold drugs on my post" he said while standing outside his William Street row house, twirling an espantoon he had just finished. "They knew they would have to answer to me" Former Commissioner Thomas C. Frazier banned espantoons in 1994, saying that they weren't all the same length and weight and that an officer twirling the stick was too intimidating to the citizenry. In one order, the Californian uprooted decades of Baltimore police history. Espantoons - the word is derived from "spontoon" a weapon carried by members of a Roman legion - were first issued to nightshift officers before the age of radio communication.

Officers used the sticks to bang on sidewalks or drainpipes to call for help. Twirling the stick became an art. "Telling a policeman not to swing his espantoon would be like asking a happy man not to whistle" The Sun said in a 1947 article. To replace the espantoons, Frazier issued long batons, called Koga sticks, which many officers refused to carry because they were cumbersome. It required hours of training in martial arts self-defense tactics, and some argued that the Koga stick was more dangerous than the espantoon. Sergeants were reluctant to send officers to Koga classes, and a trainer argued that some of the tactics being taught could be lethal on the street. Capt. Michael Andrew was among a handful of high-ranking officers who never took Koga training. He still has the espantoon his father gave him when he graduated from the police academy in 1973. His father, George Andrew, bought the espantoon from a West Baltimore Street shop when he joined the city force in 1940. The nightstick has been used ever since, "with the exception of five years when Frazier banned it, and we had to put it in mothballs" the younger Andrew said. In the old days, the espantoon was required equipment. "You better not have got caught without that stick under your arm" he said. "If you ever left it in your car, you'd get yelled at by your sergeant" The Andrews' espantoon started at the Eastern District, where his father began his career at the old stationhouse at East Fayette and North Caroline streets, and then moved with him to a foot patrol on Pennsylvania Avenue, in the Western. The nightstick is now in the hands of his son, and back on the city's east side. The 49-year-old captain addressed a group of younger officers assigned to flood the crime-troubled Eastern, and held up the espantoon as an invaluable tool for their jobs. He and other officers say that it can be used to stop threats without resorting to a gun. The elder Andrew, who retired as a lieutenant in 1974, recalled arresting a drunken blacksmith on East Fayette Street who had grabbed his legs. "I tapped him with the stick" the 86-year-old said. "He let go." Police commanders view the nightstick as an important tool that can be used to subdue people without killing them. "Mace is very effective, and it certainly has done its job" said Deputy Commissioner Bert Shirey, who still has the espantoon he was issued at the academy 34 years ago. "But there are times when Mace doesn't work, and it's nice to have something in between Mace and a gun." There is no doubt that getting hit with an espantoon hurts, and it can cause serious injury. Hlafka, who walked a beat at both the Inner Harbor and Lexington Market during his final years on the force, said he has struck many people with an espantoon over the course of his career. "People used to complain that we would hit them with the stick" Hlfaka said. "But would they rather get hit by a 9 mm bullet? Then, you don't come back"

All content herein is © 2008 The Baltimore Sun and may not be republished without permission

Law enforcement

Law enforcement

Main article: Baton (law enforcement)

Police forces and their predecessors have traditionally favored the use, whenever possible, of less-lethal weapons than guns or blades to impose public order or to subdue and arrest law-violators. Until recent times, when alternatives such as tasers and capsicum spray became available, this category of policing weapon has generally been filled by some form of wooden club variously termed a truncheon, baton, nightstick or lathi. Short, flexible clubs are also often used, especially by plainclothes officers who need to avoid notice. These are known colloquially as blackjacks, saps, or coshes.

Conversely, criminals have been known to arm themselves with an array of homemade or improvised clubs, generally of easily concealable sizes, or which can be explained as being carried for legitimate purposes (such as baseball bats and pool sticks). In addition, Shaolin monks and members of other religious orders around the world have employed cudgels from time to time as defensive weapons.

A Hlfaka Stick

Courtesy Kenny Driscoll

In his first week with the Baltimore Police Department Officer Joseph Hlafka broke five nightsticks in the line of duty. ''Four times I was protecting myself from people who wanted to bring me harm," Officer Hlafka recalled. The fifth nightstick broke after simply being dropped to the ground from a standing position. "So, I worked with a friend to make my own1 I got good at it, really good," Officer Hlafka said. "Mine don't break easily like some of the others." In making the nightsticks, Joe Hlafka uses woodworking skills he learned in the Police Boys Clubs1 and stronger wood. His colleagues liked his first models and asked him to make sticks for them. Since then, Officer Hlafka, known now as "Nightstick Joe," has made thousands of nightsticks for his fellow officers. "I realized that I would get hurt if I continued to use their [the police department's] equipment," he said. "So, I make a better nightstick. Once I made them, they started going like a house on fire." The nightsticks that Officer Hlafka, made in the basement of his south Baltimore rowhouse are requested by police officers in Baltimore and other cities in the US, and in Canada and France. "They hear about me and get in touch with me and before too long, I can make them a good nightstick," Officer Hlafka said. More than a dozen nightsticks hang from the rafters of his basement workshop, waiting to be claimed by the officers of the Baltimore Police Department. Some officers have requested terms such as "Nighty Night," "Ouch," "The Man," "Bye Bye" and "Kiss Me" to be engraved on their nightsticks. Several departmental issue nightsticks are also in Officer Hlafka’ s basement. "This is a piece of junk, 11 he says, grabbing one of the issued nightsticks that is lighter in weight than his. "I could snap it in a heartbeat." Pine nightsticks, 211/2-inches long, are issued to every trainee in the Baltimore Police Department Education and Training Division for use for in self-defense and crowd control. City officers use only wooden nightsticks, which inflict less physical damage than the plastic nightsticks used by some other police departments. Officer Hlafka uses strong bubinga wood from Brazil and South Africa, meticulously rounding and shaping each stick on his lathe. Then he sands the weapon - 24 inches long and approximately 2 inches in diameter -until it is as smooth as it can possibly get. It takes him about two hours to make a nightstick; a knocker in police parlance, Espantoon to many. He charges $30 for it, of which $5 is pure profit. $2.50 an hour1 some would say he is not in it for the money. He earns about $5 profit on each nightstick. Sgt. Th He also didn't do it for the fame, as he never knew he would become such a valuable part of Baltimore Police History. When he started there were two other stick makers that were making a name for themselves and making a splash in turning their Espantoons. Each adding something, from quality, to better woods, and designs, to going bigger and bigger and bigger until they were pushing the line in what the department would allow. But then there were things better than size, like harder woods, Nibs, and a happenstance that would change the way police would spin their sticks. It has been something that Officers have been doing since the Espantoon was introduced, give a man a stick, with a strap, and hours of alone time, and they will start to play with that stick1 spinning it around backward and forward, trying to keep it going without tangling it up like a telephone cord. Two spins forward two spins back, and so on and so on. One day after a hard shift Joe came home dropped his keys on his coffee table and took a quick nap, as he was waking up, he saw his key chain laying there and he couldn't help but notice the strap on his keys was only slightly wider than the strap on his nightstick. So, coming up with a quick idea he grabbed his keys and off to the workshop he went, before long he had made several attempts to find the sweet spot as to where it worked best, and the rest is history. Now with a swivel in the strap, the stick can be spun for an unlimited number of revolutions, forward or backward without any problems. Thomas Maly who worked in the education and training division, said it's somewhat of a tradition for new officers to buy their nightsticks from Nightstick Joe. "A lot of them seem to like his nightsticks," said Sergeant Maly. "They conform to the same standards but have a different finish. They're more perfect." Officer Hlafka said he never imagined the popularity of his nightsticks. "But I've done pretty well over the years, and I guess the nightsticks have too," he said. "I make it to last because it should last, and I make them any way that they want to have them made. I think that I've known every officer on the [city] force for the last 20 or more years." A foot patrolman assigned to the tactical section at the Inner Harbor, he works an eight-hour night shift, then puts in four to six hours making the "Nightstick Joe model nightstick” When he's in his workshop, he and his wife communicate through an intercom system. "The only thing that changes on each nightstick is the Barrel-Head. The rest of it is the same. People have different grips," he said. "When an officer grabs a piece of wood, it's got to feel comfortable." Officer Hlafka said he's used two nightsticks since he began making them. "The first one I made, I had for almost 10 years until it was stolen. The one I have now I've had for 15 years," he said. Captain Michael Bass, of the Northern District1 said Officer Hlafka is somewhat legendary because of his nightsticks. "You mention his name, and everybody says, 'Oh yeah, I know him,' Captain Bass said. when he was assigned to the police academy, Officer Hlafka would meet with most trainees, show them his nightsticks, and take their orders. "And then a couple of weeks later, he'll pull up and pass them out," said the captain.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction or distribution is prohibited without permission. If not for the three artisans Carl Hagen, Edward Bremer, and Officer Joseph “Nightstick Joe" Hlafka we might not have seen the changes we have seen in the Baltimore Espantoon. Before these three there were a few interesting changes made; officers used to take the issued sticks before staining it they would carve or sand the curved portion of the Barrelhead down to being more tubular in shape. Once it was all straight, they would carve several ring grooves, sand if smooth and stain it, often the stain was iodine from the radio cars first aid kit and apply it with the gauze pads. Then rather than a clear coat, they would burnish the stick. We have a few of these altered sticks, and I must say as nice as it was, I am thankful for the work of Mr. Hagen, Mr. Bremer, and Officer Hlafka.

A Hlfaka Stick

A Hlfaka Stick

This has a nice Finger Grip cut into the shaft so the officer can get a better grip while swinging that oversized Barrel head.

Espantoon

The Espantoon is a wooden police baton equipped with a long leather strap for twirling. It originated, and is still strongly associated, with the Baltimore Police Department in the city of Baltimore, Maryland. The term is considered distinctly Baltimorean. The word itself derives from that of a pole weapon, the spontoon, which was carried by infantry officers of the British Army during the Revolutionary period. Since, the espantoon has been considered a symbol of the "policeman's office and dignity". Before the advent of wireless communications, the espantoon was reportedly used by Baltimore policemen to call for assistance where its user would bang it on the curb or a drainpipe.

In 1994, Thomas C. Frazier took over as Baltimore's police commissioner and banned the espantoon. Frazier, a Californian, believed that the device, and the policemen's twirling of it, was intimidating to the civilian populace. He attempted to replace it with another weapon, the koga. Many officers, however, felt that the koga was cumbersome, difficult to master, and even more dangerous than the espantoon.

In 2000, Edward T. Norris assumed the office of police commissioner and lifted the ban on the espantoon, although he did not mandate its use. The move was made as part of a general effort to boost morale and instill a more aggressive approach to policing in Baltimore. Norris stated, "When I found out what they meant to the rank and file, I said, 'Bring them back.' ... It is a tremendous part of the history of this Police Department."

The Billy Club (also referred to as a truncheon, or baton) is a short stick used defensively as a bludgeoning weapon, typically by law enforcement. Billy Clubs can be manufactured using wood, plastic, steel or a combination of the three. They are easily concealable, usually less than an arm's length in size, and specifically designed to be used as a non-lethal means of subduing an attacker, or a non-compliant person. In the photo above we have 6 sticks, the top two sticks are issued Baltimore Police Sticks, the 3rd stick down from the top is a Carl Hagen, Espantoon, the 4th stick down is also an issued stick, (it seemed from time to time when the department ran low on or out of the standard issue, they would pick up some of these from Howard Uniform and issue them. The 5th stick down is a Joe "Nightstick Joe" Hlfaka Nightstick, or Espantoon, and the 6th stick is a presentation stick, these typically had a braided rope that went from the thong grove and hung down the shaft, while another braided rope came up and attached to the ball spindle atop the barrel head/handle, in sticks 1 thru 5 the stick was held at the bottom of the shaft and the barrel head (handle looking part is swung) in stick buner 6 the handle is the barrel head, and the braded ropes acts as a way of holding on to the baton. If you look at the shaft on all six sticks, you'll notice that are the same diameter from the ring stop next to the thong groove, to the top of the shaft, whereas a Billy club tapers out as it travels down the shaft away from the ring stop.

Finger Grip Metal Truncheon

Joe's Nightstick

Nightstick History/Info/Silliness

Unknown Author (Possibly Bill Hackley)

When I started out, the older officers often had a short, hard-rubber club they carried in the sap pocket on the leg seam of their uniform trousers. They referred to it as a "Day Billy", harkening back to a time when the day shift on a police department was a fairly quiet affair. When the sun went down and the crazies came out, however, they parked the Day Billy and picked up a "Nightstick". Most of us also carried a slap-jack, or "convoy" blackjack tucked in a pocket in case we were inadvertently caught somewhere without a stick. Like in a diner during a meal break, or at turn-key downtown. You were expected to always use an impact tool. If you hurt your hand from punching someone, and had to go off on injured status, you were forcing someone else to leave their job to cover your beat. Getting injured legitimately was expected, but getting hurt foolishly was considered to be bad form.

Being an avid law enforcement history buff, I learned over my 38 year career that there often is a lot of tradition, and a lot of really fun stories, attached to the various styles and configurations of nightsticks and billies used by the different agencies across this country. I've managed to collect quite a number of 'signature' sticks from various LE departments while I was on the job. It's hard for me now to pick one of them up, and heft it in my hand, and not recall the first time I stepped out of a cruiser at a disturbance call, my new gun-belt creaking stiffly, and remember the first time anyone ever came up to me and said, "There, Officer...it's that blue house with the chain link fence". In time, I got to visit LE agencies in other parts of the country and was always fascinated by their impact weapons, and the local history attached to them.

Sometimes it involved the type of nightstick issued at an agency. Like the espantoon used by the coppers at Baltimore PD. If you aren't aware of it, the espantoon outwardly looks like a standard old-style nightstick. However, it was modified slightly in shape and the design of its leather thong and held in the opposite way a normal nightstick was held. That is, you conked miscreants with what most of us would identify as the knurled "handle" end of the stick, not the "barrel" end. I've heard a couple of different stories as to why the espantoon is employed that way, and how it came by its name. I'm not sure anyone knows for sure, but it's a neat story.

Contrast that with the lance-like 26-inch "Koga" style nightsticks that gained favor on the west coast in the 1970's, supplanting the older style nightsticks with the leather thong that beat cops had used for years. The trim, unadorned "Koga" stick represented a formalized system of close quarters hand-to-hand control over out-of-control trouble makers. The first real martial arts based system of stick use that I recall being taught to street cops in this country. Most of us had only been taught a few choke holds and come-alongs at the academy, along with hours of striking and short-sticking the heavy bag at the gym. Give a determined road-dog copper a Dynawood Koga-style nightstick, and a modicum of training, and you couldn't find anyone in the county who could whip him in a fight.

At a lot of police departments, either the agency issued a cheap POS nightstick, or it required each officer to procure his own "knocker". If you poke around in the history of those departments, you'll generally come upon the name of one or two officers who, as a side-line back in the day, turned out high quality nightsticks and made a few bucks selling them to everyone. The makers didn't charge much for a nightstick because their brother officers couldn't afford much on the skinny salaries they made. These were sticks that had an identifiable style of manufacture that soon became the signature tool of that agency, often nearly as identifiable as the agency's badge or shoulder emblem. The stick makers' names are all but lost in the mists of time now. Names like Tony Barsotti at San Francisco PD, Ernie Porter at Cincinnati PD, or Joe Hlafka at Baltimore. You can spot those sticks by their contours just as sure as if the maker's mark had been burned into the wood.

Frankly, I've always thought the real advantage to working in uniform was that you could nonchalantly carry a real club when you were in public and on a job, and no one gave you a second glance. The old cops told me to "take his wind, or take his wheels" when fighting a high-end resister, and I quickly learned the effectiveness of a short-stick jab to the solar plexus, a full-power smash to the short ribs, or well centered strike at the back of the thigh or calf muscle. The idea was to debilitate and wear down a resister, bring him back under control and get him cuffed up. "Don't cripple him, if you don't have to", one old timer told me, "Just take the starch out of him and bring him in". Damned if it didn't work as well, or better, than anything invented since.

That's what the nightstick represented then. Carried idly in your hand, twirled at the end of a leather thong, or dangling from a gun belt, it was the visible symbol of the restrained presence that characterizes the American police officer. I know that when I started out some of the old sergeants actually discouraged anyone from wearing a baton ring on your gun belt. They believed that stick should always be in your hand, or tucked under your arm as you scribbled in your notebook. I rebelled, being a practical sort, and started wearing a baton ring as soon as I got off probation in the spring of 1972. Then, as now, there was a lot of anarchist sentiment in the country and assaults on LEO's were high. Having my stick in a ring on my belt cut down on the chances of some chud getting it and getting himself shot for his efforts.

You remember what a CHUD is, right? A "Citizen Having Urban Difficulties"?

In time I tried using nightsticks made of polycarbonate plastics, even briefly tried one made out of aluminum. The only one that felt good in my hands was an 18-inch-long "Billy" made by Monadnock that I bought about 30 years ago. It had a slightly oversized grip which fit nicely in my oversized hands and was marketed as the "Tuff Boy" model. It sure lived up to its name. It didn't warp out of shape if you left it locked in the car during the summer, was fast-handling and darn near stout enough to hammer fence posts into the ground. But, being a short "Billy", it was never as versatile as the 24 or 26-inch hardwood nightsticks were.

History

19th-century police truncheons in the Edinburgh Police Centre Museum - A modern wooden baton. In the Victorian era, police in London carried truncheons about one-foot long called Billy clubs. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, this name is first recorded in 1848 in American English as slang for a burglars' crowbar. The meaning "policeman's club" is first recorded 1856. The truncheon acted as the policeman's 'Warrant Card' as the Royal Crest attached to it indicated the policeman's authority. This was always removed when the equipment left official service (often with the person who used it). Earlier on the word was used in vulgar Latin (bastο - a stick helping walking from basta - hold).

The Victorian original has since developed into the several varieties available today. The typical truncheon is a straight stick made from wood or a synthetic material, approximately 1.25 inches (32 mm) in diameter and 18–36 inches (460–910 mm) long, with a fluted handle to aid in gripping. Truncheons are often ornamented with their organizations' coats of arms. Longer truncheons are called "riot batons" because of their use in riot control.

Truncheons probably developed as a marriage between the club or military mace and the staff of office/scepter.

Straight batons of rubber have a softer impact. Some of the kinetic energy bends and compresses the rubber and bounces off when the object is struck. The Russian police standard-issue baton is rubber, except in places such as Siberia, cold enough that the rubber can become brittle and break if struck.

The traffic baton is red to make it more visible as a signaling aid in directing traffic. In Russia traffic batons are striped in black and white for the same reason.

Until the mid-1990s, British police officers carried traditional wooden truncheons of a sort that had changed little from Victorian times. After the early 1990s, forces replaced truncheons with side-handle and collapsible batons for all but ceremonial duties.

The BPD used to use two kinds of batons depending on the time. The one for daytime was called a day-stick and was 11 inches in length. Another baton, that was used at night, was 26 inches long and called a night-stick, which is where the word nightstick came from. The night-stick was longer so it could provide extra protection which was thought to be necessary at night.

Mounted Unit

Horses working in riot control wear facial armor, made of Perspex so that the animals can still see. The officers themselves are often equipped with especially long wooden or polycarbonate baton nightstick for use on horseback, as standard patrol baton would have insufficient length to strike or control individuals at ground level, so length would be important.

This is San Francisco PD Mounted 1967

Police’s Spurn City’s Nightsticks, Buy Their Own

Jun 27, 1977

The nightstick is a very special thing to a Baltimore city policeman. Rather than simple piece of wood to be used in a line of duty, the nightstick is seen as a constant companion and even a lifesaver. As Sgt. Larry Leeson, a police spokesman said recently, “It is like his best friend almost.” And as one exercises care in choosing a best friend, policeman are very careful in selecting a nightstick. They have a definite ideas about how big and how heavy the stick should be to do the job effectively. Many offices enjoy carrying a stick that has some feature that makes it uniquely their own. The strapless, 21 inch long, inch and a half wide, unfinished nightsticks issued by the city Police Department to each of its officers just don’t measure up, many policemen say, thus it has become a tradition for many officers to buy their own longer, thicker, heavier and fancier nightsticks. A supplier of such nightsticks whose products are currently in vogue with the police department is Edward W Bremer, 75, who said recently that he has sold more than 300 of his $12 sticks during the three years in business – mostly to officers who have just graduated from the Police Academy. Mr. Berman believes the policeman come to him rather than buying one from a large commercial supplier “because they like the fact that I’ll make it the way they want.” He gives the officers their choice of wood, which determines the weight and force of impact the stick will have. “I have made some of the long as 26 inches and some 2 ½ inches in diameter” Mr. Bremer said the biggest and hardest nightsticks are usually ordered by policeman serving the “Western or Northwest district” he said.

Mr. Brammer stains the sticks in the color of the officer’s choice and attaches braided leather strap with a metal swivel so the stick can be twirled with a flick of the rest. “Some policeman like a little nib on the end of the stick to poke in stomachs.” He said. Despite the sadistic sound of it, Mr. Brammer has a sense of high purpose in his work. The nightsticks issued by the department, referred to by one officer as “toothpicks”. Our smaller and lighter than the sticks he makes. Mr. Brammer believes “because they just don’t want nobody to get hurt.” But a nightstick, he maintains, is a defensive weapon.

“It’s supposed to be able to knock somebody out.” He said, “A policeman with a heavy stick in his hand has a feeling of protection. A light stick is no protection at all. The boys patrolling the beat in the some bad characters. They want their stick good and heavy.” Mr. Brammer recalled that he was in his boyhood when he “took a liking” the police officers. “A lot of my friends joined the police force,” he said. “So I want to give them something that will do the job and keep them out of trouble.”

Officer stationed throughout the city, some of them carry Mr. Brammer’s creations, echoed his views. Many also confessed to a sentimental attachment to the nightsticks. A stick that is distinctive in some way or was passed down by a friend or relative who has retired from the department is a source of pride, several officers said. They also stubbornly cling to the old-fashioned term, “espantoon,” when referring to nightsticks and their reports.

Mr. Brammer said he is very discerning about who buys his products. He deals only with policeman or security guards who show identification, he said “I’m not going to sell to every Tom Dick and Harry” he said he was glad to make 10 inch, purse sized to sticks for women who feel they need protection themselves Mr. Brammer said.

A retired custom home builder and lifelong amateur carpenter, Mr. Bradner began turning out nightsticks and little workshop near his home in the 3500 block of old York Road as a way to fill his idle time. He said he doesn’t earn much of a profit when the sticks. “But even if I don’t make any money, it would give me something to do,” he said. “Anyone that retires without something do this for us.” Jimmy Distler

Andre Nock

Top stick a Late 50's Issued Stick, Bottom Nightstick Joe turned stick

Oversized stick, it is hard to say for sure who made this, but it is turned in Joe's style

Nightstick Joe - Guaranteed Hobby

11 April 1983

Joe Hlafka gives a lifetime guarantee with every nightstick he sells. If you bash someone over the head with it and it breaks, who replace it free. That's how sore he is of the quality of his work. Joe Hlafka a.k.a. nightstick Joe to dozens of his friends and acquaintances – is a squat, heavyset, 45-year-old city policeman who is turned a hobby, woodworking, into a lucrative part-time business.

Working in wood shavings up to his ankles in hit the basement of his South Baltimore row home, he turns out everything for nightsticks and walking sticks to children's toys and puzzles – all of which he sells at bargain basement prices he charges $20 plus tax for example for one of his walking sticks but he estimates it cost him almost $16 to make and that doesn't include his labor. Similarly he sells nightsticks that he says cost him about 10 or $12 to make for $17 plus tax why because he's not in it for the money. It's a hobby something I do after work to unwind, he says some people like to go out and have a couple of beers. Me I like to come home and make things that's how I relax. Besides, he thinks it's a moral for anyone to make a huge profit. My father always told me, if you serve the masses see your eat with the classes. I believe that. I tried to concentrate on volume, and that way I'm able to keep my prices low and still make a few dollars myself. Most of Mr. Hopkins it's pronounced Hlafka as if the H was silent nightsticks are sold by word-of-mouth to individual policeman or to a plea supply house – some as far away as Florida and Texas. Nightsticks are heavier and sturdier than regulation nightsticks they weigh 12 1/2 to 14 ounces and they cost about $10 more but their superior to anything that mass-produced Mr. Hlafka says and they meet all police standards. There made a Purple Heart, a door bolt, purple color wood grown in the South, or Bubinga, a strong West African wood similar to a Rosewood.

For civilians, including the elderly who want canes that also can be used for protection, there are custom-made nightstick Joe Hlafka walking sticks, longer and thicker than nightsticks, and much more elaborate. The handles our brass usually in the shape of an animal head and intricate diamond, spiral or fluted designs are carved with a router into the shaft both the walking sticks and nightsticks are soaked in linseed oil tried and see over the polyurethane to protect them for moisture, which is the enemy of wood. So, oddly enough is rein or the lack of it.

A poor rainy season can slow a trees growth and create weak spots in the wood, Mr. Hlafka claims. He says the weak spots are not always noticeable, and the wood may break if it hit something hard enough. I've tested the nightsticks with a hydraulic gauge, and I can apply 110 pounds of pressure per square inch before the Purple Heart cracks. The Bubinga will take 210 pounds per square inch. But if there is a weak spot in the wood, the crack a lot faster. That's why I guarantee my sticks. You never know when you might get one that's bad

Joe Hlafka, was born and raised in South Baltimore, and has been a policeman for 13 years. He started in Western District and transferred to the traffic division two years ago. His beat is a North Charles and Saratoga Street area where he's known for his a viable good humor. One of his favorite ploys is to travel along the street hawking parking tickets for drivers whose cars are parked in no parking zones – a nice gesture according to one N. Charles St. merchant who says the policeman makes a point without offending people. According to Police Department records Mr. Hlafka has been shot six times in the line of duty. He was cited a few months ago for his part in foiling a robbery at Charles Center bank is married and credits his wife Adella withholding the marriage together, for 25 years, I've always been able to talk to her and discuss things he said, and that's helped me handle the stress of police work. The couple has three daughters, a son Joe Junior died a few years ago. Mr. Hlafka plays trombone in the Baltimore City Police Department Dance Band, Sounds of an Era, which performs for community groups, and he participates in a federally funded police program to get drunk drivers off the road.

He began doing woodworking when he was 9 or 10 years old. I join the police boys club and started making fancy lamps and things it's something I've always enjoyed doing, but I've never sold anything up until a couple of years ago, when I started making police nightsticks since then he estimates he made almost 500 nightsticks and another 200 walking sticks. He's gotten inquiries from cities in France and England, He started making children's toys a few months ago after he became bored with making nightsticks his first effort was a wooden pull train. It turned out to be an excellent choice.

The little five car train engine, coal tender, boxcar, tanker car, and caboose are probably the most popular toy their guy will up by appreciative parents almost as fast as he can make them small wonder he sells them for $25 about half what comparable trains cost in most toy stores Mr. Hlafka says.

He also makes chunky little tugboats, blocky old-fashioned cars models of famous “Black Maria” a police patrol wagon and assortment of simple wooden animal puzzles squirrels ducks kittens range in prices for about $5-$7 anytime I see something I think I can do it's fun for me it's like a challenge to see if I can do it and maybe improve on it. I've always believed the world is limited only by the person's capacity to dream. Lately Mr. Hlafka’s, he says, and that’s helped me handle the stress of police work.

Mr. Hlafka’s dreams seem to be getting bigger he’s talking about building furniture he says he got the idea after he saw a kit for grandfathers clock advertised in a magazine for hundred and $60. Naturally he thought the price was too high. I can do it for a lot less than that he says for more information call

Several readers have commented on the Espantoon -- defined in Webster's Third Edition: "In Baltimore, a policeman's stick" -- and one asked for a picture of one. Here are a couple by Sun photographer Amy Davis shot back in 2000 when then Police Commissioner Edward T. Norris reversed a ban and allowed officers to carry the sticks once again. Tradition returned. Here is "Nightstick Joe" making an Espantoon in the basement of his Federal Hill rowhouse in 2000, and another of him outside with the stick. What follows is the complete story published on Sept. 23, 2000, that I wrote on the return of the Espantoon. I've been warned against posting long takes from old stories, but so many want to know the history I think some of you might be interested:

By Peter Hermann

Nightstick Joe is Back in Business.

To the delight of tradition-minded Baltimore police officers, the city's new commissioner agreed yesterday to allow his troops to carry the once-banned espantoon, a wooden nightstick with an ornately tooled handle and a long leather strap for twirling. Joseph Hlafka, who retired last year after three decades as an officer on the force and is best known by his nickname earned for turning out the sticks on his basement lathe, will once again see his handiwork being used by officers patrolling city streets.

Orders for the $30 sticks are coming in. A local police supply store has ordered three dozen to boost its stock. Commissioner Edward T. Norris bought five. Young officers who have never seen one are calling with questions. "They want to know how to twirl it," Hlafka said. Before Norris arrived from New York in January, he had never heard of an "Espantoon." He knew the generic "Baton," "Nightstick" and "Billy club," and was well acquainted with New York's technical "PR-24." He challenged his command staff to prove the term belongs solely to Mob-town. And there, in Webster's Third Edition: "Espantoon, Baltimore, a policeman's club."

Norris signed the order yesterday, and the espantoon once again became a sanctioned, but optional, piece of police equipment. "When I found out what they meant to the rank and file, I said, `Bring them back,'" said Norris, who is trying to boost morale. "It is a tremendous part of the history of this Police Department." Hlafka is delighted. When the sticks were barred in 1994 by a commissioner who didn't like them, his production dropped from about 70 a month to 30, with most of them going to officers in departments across the country and collectors. They are now made from blocks of Bubinga, a hardwood imported from South Africa that doesn't get brittle in cold weather. Hlafka whittles and sands the wood to remove visible blemishes on the sticks, which measure from 22 inches to 25 inches long. It is art with a purpose. The espantoon recalls the bygone times of Baltimore law enforcement, when running afoul of an officer meant trouble. It fits in with the city's new assertive policing strategy of a new department leader who wants "police to be the police again."

It is just what Hlafka, 62, wants to hear. "No one sold drugs on my post," he said while standing outside his William Street rowhouse, twirling an espantoon he had just finished. "They knew they would have to answer to me." Former Commissioner Thomas C. Frazier banned espantoons in 1994, saying that they weren't all the same length and weight and that an officer twirling the stick was too intimidating to the citizenry. In one order, the Californian uprooted decades of Baltimore police history. Espantoons - the word is derived from "spontoon," a weapon carried by members of a Roman legion - were first issued to nightshift officers before the age of radio communication.

Officers used the sticks to bang on sidewalks or drainpipes to call for help. Twirling the stick became an art. "Telling a policeman not to swing his espantoon would be like asking a happy man not to whistle," The Sun said in a 1947 article. To replace the espantoons, Frazier issued long batons, called Koga sticks, which many officers refused to carry because they were cumbersome. It required hours of training in martial arts self-defense tactics, and some argued that the Koga stick was more dangerous than the espantoon.

Sergeants were reluctant to send officers to Koga classes, and a trainer argued that some of the tactics being taught could be lethal on the street. Capt. Michael Andrew was among a handful of high-ranking officers who never took Koga training. He still has the espantoon his father gave him when he graduated from the police academy in 1973. His father, George Andrew, bought the espantoon from a West Baltimore Street shop when he joined the city force in 1940. The nightstick has been used ever since, "with the exception of five years when Frazier banned it, and we had to put it in mothballs," the younger Andrew said.

In the old days, the espantoon was required equipment. "You better not have got caught without that stick under your arm," he said. "If you ever left it in your car, you'd get yelled at by your sergeant." The Andrews' espantoon started at the Eastern District, where his father began his career at the old stationhouse at East Fayette and North Caroline streets, and then moved with him to a foot patrol on Pennsylvania Avenue, in the Western. The nightstick is now in the hands of his son, and back on the city's east side. The 49-year-old captain addressed a group of younger officers assigned to flood the crime-troubled Eastern and held up the espantoon as an invaluable tool for their jobs.

He and other officers say that it can be used to stop threats without resorting to a gun. The elder Andrew, who retired as a lieutenant in 1974, recalled arresting a drunken blacksmith on East Fayette Street who had grabbed his legs. "I tapped him with the stick," the 86-year-old said. "He let go." Police commanders view the nightstick as an important tool that can be used to subdue people without killing them. "Mace is very effective, and it certainly has done its job," said Deputy Commissioner Bert Shirey, who still has the espantoon he was issued at the academy 34 years ago. "But there are times when Mace doesn't work, and it's nice to have something in between Mace and a gun."

There is no doubt that getting hit with an espantoon hurts, and it can cause serious injury. Hlafka, who walked a beat at both the Inner Harbor and Lexington Market during his final years on the force, said he has struck many people with an espantoon over the course of his career. "People used to complain that we would hit them with the stick," Hlafka said. "But would they rather get hit by a 9 mm bullet? Then, you don't come back."

All content herein is © 2008 The Baltimore Sun and may not be republished without permission.

POLICE INFORMATION

Copies of: Your Baltimore Police Department Class Photo, Pictures of our Officers, Vehicles, Equipment, Newspaper Articles relating to our department and or officers, Old Departmental Newsletters, Lookouts, Wanted Posters, and or Brochures. Information on Deceased Officers and anything that may help Preserve the History and Proud Traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items