Terry vs Ohio

Terry vs Ohio

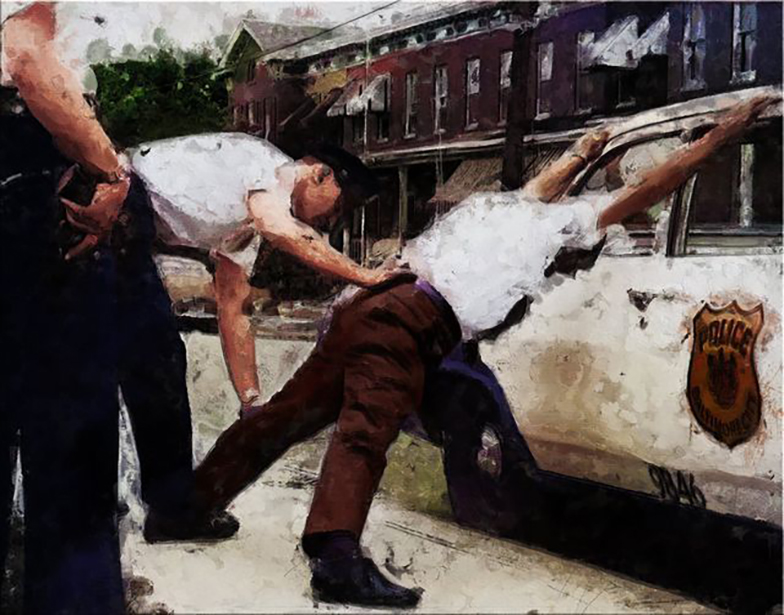

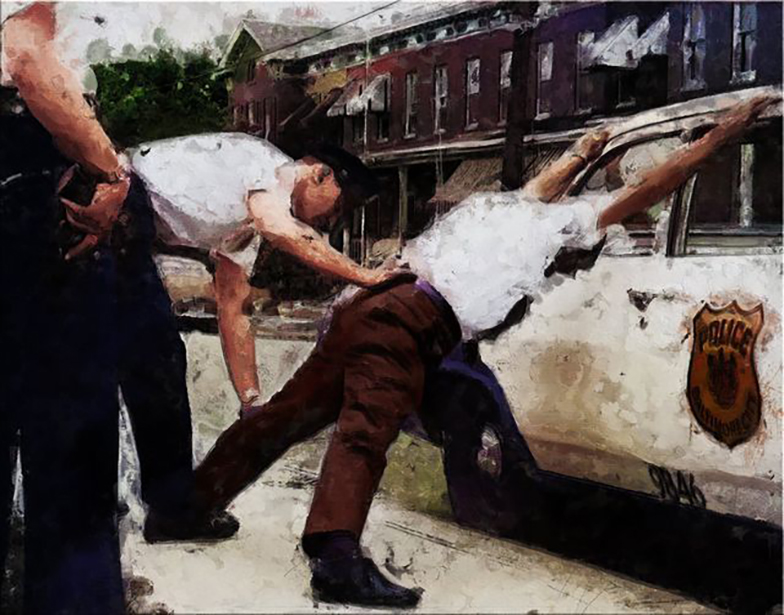

The Terry case involved an incident that took place on October 31, 1963, in Cleveland, Ohio. Police officer Martin McFadden was on duty in downtown Cleveland and noticed two men standing on a street corner. One of the men, John W. Terry, walked down the street, stopped in front of a certain store and looked through its window, then briefly continued on before turning around and returning to where he started, stopping on his way back to look in the store window again. The other man, Richard Chilton, then did the same. McFadden watched the pair repeat this routine about a dozen times. A third man then joined Terry and Chilton and the three walked up the street together toward the store. McFadden suspected that the men had been "casing" the store in preparation for robbing it, so he followed and confronted them. He asked the men's names, but they gave noncommittal mumbling answers. McFadden then grabbed Terry and Chilton, spun them around, patted down their exterior clothing, and discovered that they both had pistols in their jacket pockets.

McFadden arrested Terry and Chilton, and they were charged in the Cuyahoga County Court of Common Pleas with illegally carrying concealed weapons. At trial, Terry's lawyer filed a motion to suppress the evidence of the discovered pistol, arguing that the "frisk" had been a violation of the Fourth Amendment and therefore the pistol McFadden discovered during it should have been excluded from evidence under the exclusionary rule. The trial judge denied his motion on the basis that the "stop-and-frisk" was generally presumed legal, and Terry was convicted. He appealed to the Ohio District Court of Appeals, which affirmed his conviction, then appealed to the Supreme Court of Ohio, which dismissed his appeal. He then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which agreed to hear his case and granted certiorari.

Supreme Court decision

On June 10, 1968, the Supreme Court issued an 8–1 decision against Terry that upheld the constitutionality of the "stop-and-frisk" procedure as long as the police officer performing it has a "reasonable suspicion" that the targeted person is about to commit a crime, has committed a crime, or is committing a crime, and may be "armed and presently dangerous".

Opinion of the Court

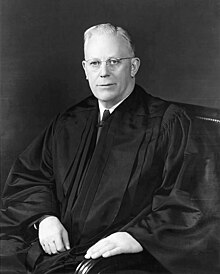

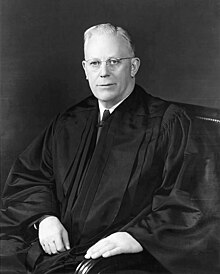

Chief Justice Earl Warren,

The author of the majority opinion in Terry

Eight justices formed the majority and joined an opinion written by chief justice Earl Warren. The Court began by accepting Terry's arguments, which Ohio had disputed, that policeman McFadden's stopping, questioning, and frisking of Terry and Chilton constituted actual "searches" and "seizures" under the Fourth Amendment. But the Court ruled that the Fourth Amendment "searches" and "seizures" that occurred during a "stop-and-frisk" were not "unreasonable" under the Amendment's first clause. Both the initial "stop" and the subsequent "frisk" were so "limited" and "brief" that a lesser justification sufficed, rather than requiring the police to have probable cause beforehand.

If this case involved police conduct subject to the Warrant Clause of the Fourth Amendment, we would have to ascertain whether "probable cause" existed to justify the search and seizure which took place. However, that is not the case. We do not retreat from our holdings that the police must, whenever practicable, obtain advance judicial approval of searches and seizures through the warrant procedure, or that in most instances failure to comply with the warrant requirement can only be excused by exigent circumstances. But we deal here with an entire rubric of police conduct—necessarily swift action predicated upon the on-the-spot observations of the officer on the beat—which historically has not been, and as a practical matter could not be, subjected to the warrant procedure. Instead, the conduct involved in this case must be tested by the Fourth Amendment's general proscription against unreasonable searches and seizures.

— Terry, 392 U.S. at 20 (citations omitted).

Reasoning that police officers' need to protect themselves outweighed the limited intrusions involved, the Court ruled that officers could "stop" a person if they had "reasonable suspicion" that criminal activity was afoot, and could then "frisk" the person who was stopped if they had "reasonable suspicion" that the person was "armed and presently dangerous." Neither intrusion required that police have the higher level of "probable cause" that would be needed to arrest or to conduct a full search. The Court defined this new, lesser standard of "reasonable suspicion" as being less than "probable cause" but more than just a hunch, stating that "the police officer must be able to point to specific and articulable facts which, taken together with rational inferences from those facts, reasonably warrant [the] intrusion."

Our evaluation of the proper balance that has to be struck in this type of case leads us to conclude that there must be a narrowly drawn authority to permit a reasonable search for weapons for the protection of the police officer, where he has reason to believe that he is dealing with an armed and dangerous individual, regardless of whether he has probable cause to arrest the individual for a crime. The officer need not be absolutely certain that the individual is armed; the issue is whether a reasonably prudent man in the circumstances would be warranted in the belief that his safety or that of others was in danger. And in determining whether the officer acted reasonably in such circumstances, due weight must be given, not to his inchoate and unparticularized suspicion or "hunch," but to the specific reasonable inferences which he is entitled to draw from the facts in light of his experience.

— Terry, 392 U.S. at 27 (footnotes and citations omitted).

The Court held that this "reasonable suspicion" standard must apply to both the initial stop and the frisk. First, it said that a police officer must have reasonable suspicion to stop a suspect in the first place. Second, it held that an officer could then "frisk" a stopped suspect if he or she had reasonable suspicion that the suspect was armed and dangerous, or if, in the officer's experience, the suspected criminal activity was of a type that was "likely" to involve weapons. The officer's "frisk" could only be for the sole purpose of ensuring the suspect was not armed, and so had to be limited to a pat-down of the suspect's outer clothing.

The Court then applied these legal principles to McFadden's actions with Terry and found that they comported with the "reasonable suspicion" standard. McFadden had years of experience as a policeman and was able to articulate the observations that led him to suspect that Terry and the other men were preparing to rob the store. Since McFadden reasonably suspected that the men were preparing for armed robbery, he reasonably suspected that Terry was armed, and so his frisk of Terry's clothing was permissible and did not violate Terry's Fourth Amendment rights.

The Court ended its opinion by framing the issue very narrowly, saying the question it was answering was "whether it is always unreasonable for a policeman to seize a person and subject him to a limited search for weapons unless there is probable cause for an arrest." In answer to this limited question, the Court said it was not. It ruled that when an American policeman observes "unusual conduct which leads him reasonably to conclude in light of his experience that criminal activity may be afoot and that the persons with whom he is dealing may be armed and presently dangerous", it is not a violation of the Fourth Amendment for the policeman to conduct a "stop-and-frisk" of the people he suspects.

Concurring opinion of Justice White

Justice White joined the opinion of the Court but suggested that

There is nothing in the Constitution which prevents a policeman from addressing questions to anyone on the streets. Absent special circumstances, the person approached may not be detained or frisked but may refuse to cooperate and go on his way. However, given the proper circumstances, such as those in this case, it seems to me the person may be briefly detained against his will while pertinent questions are directed to him. Of course, the person stopped is not obliged to answer, answers may not be compelled, and refusal to answer furnishes no basis for an arrest, although it may alert the officer to the need for continued observation.

With regard to the lack of obligation to respond when detained under circumstances of Terry, this opinion came to be regarded as persuasive authority in some jurisdictions, and the Court cited these remarks in dicta in Berkemer v. McCarty, 468 U.S. 420 (1984), at 439. However, in Hiibel v. Sixth Judicial District Court of Nevada, 542 U.S. 177 (2004), the Court held that neither of these remarks was controlling in a situation where a state law required a detained person to identify himself.

Dissenting opinion of Justice Douglas

Justice William O. Douglas strongly disagreed with permitting a stop and search absent probable cause:

We hold today that the police have greater authority to make a 'seizure' and conduct a 'search' than a judge has to authorize such action. We have said precisely the opposite over and over again.

To give the police greater power than a magistrate is to take a long step down the totalitarian path. Perhaps such a step is desirable to cope with modern forms of lawlessness. But if it is taken, it should be the deliberate choice of the people through a constitutional amendment.

POLICE INFORMATION

If you have copies of: your Baltimore Police Department Class Photo, Pictures of our Officers, Vehicles, Equipment, Newspaper Articles relating to our department and or officers, Old Departmental Newsletters, Lookouts, Wanted Posters, and or Brochures. Information on Deceased Officers and anything that may help Preserve the History and Proud Traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to Honor the fine men and women who have served with Honor and Distinction at the Baltimore Police Department. Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. follow us on Twitter @BaltoPoliceHist or like us on Facebook or mail pics to 8138 Dundalk Ave. Baltimore Md. 21222

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll