Drunk-o-meter and Breathalyzer

Alco-Sensor III

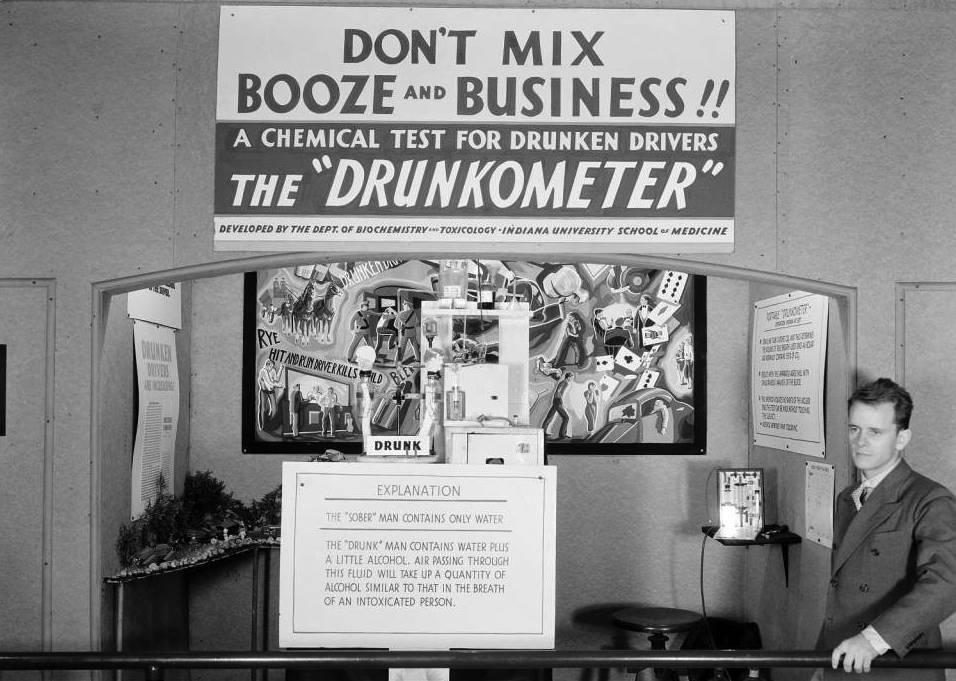

Drunk-O-Meter

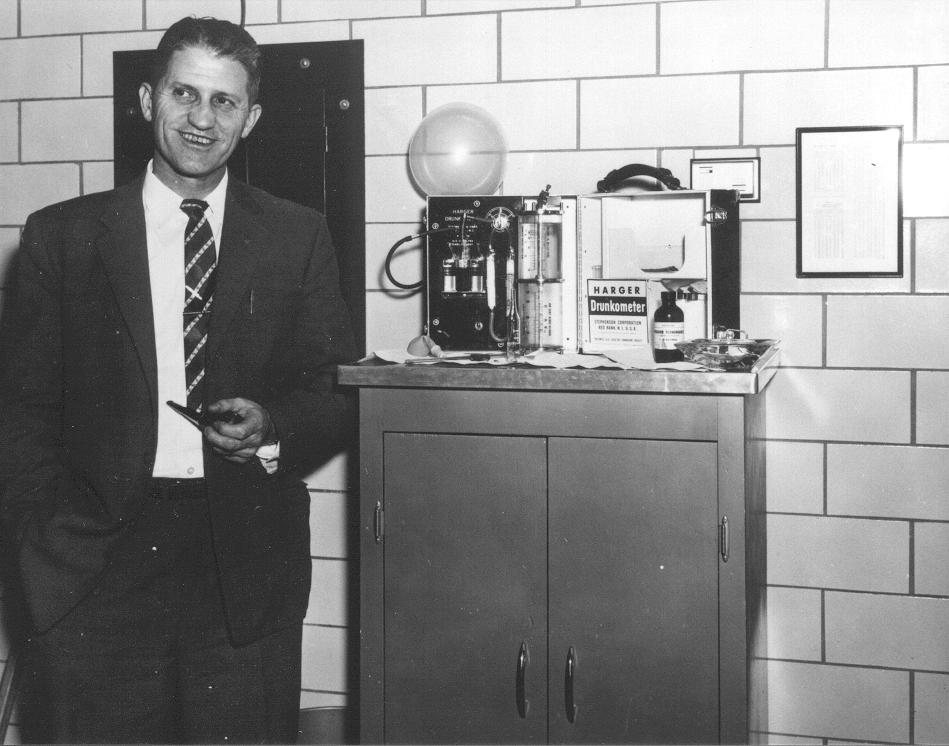

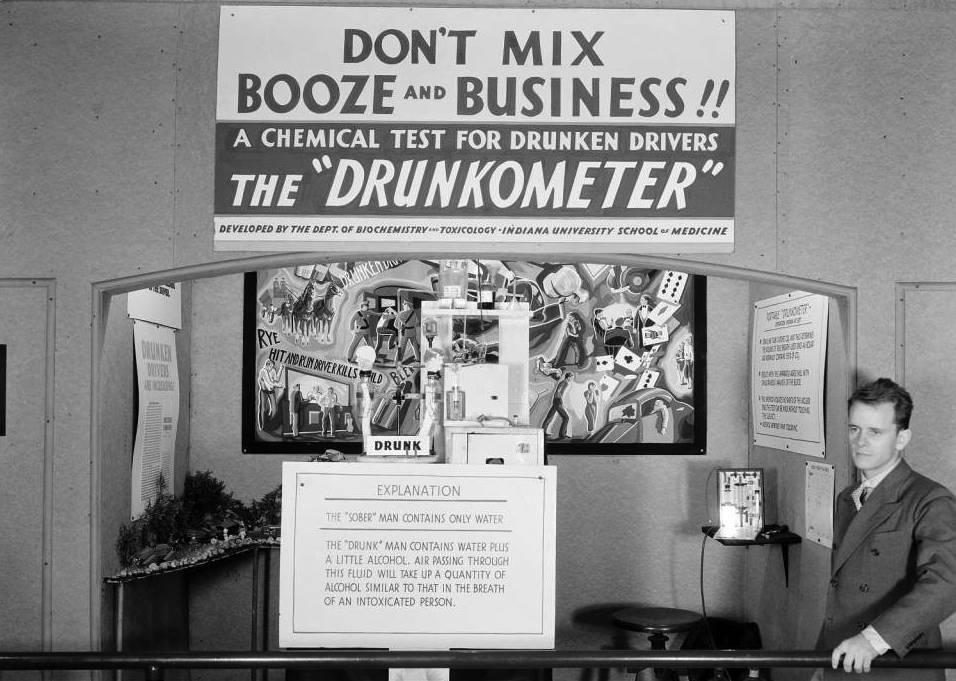

In the United States, the first laws against operating a motor vehicle while under the influence of alcohol went into effect in New York in 1910. In 1936, Dr. Rolla Harger, a professor of biochemistry and toxicology, patented the Drunkometer, a balloon-like device into which people would breathe to determine whether they were inebriated. In 1953, Robert Borkenstein, a former Indiana state police captain and university professor who had collaborated with Harger on the Drunkometer, invented the Breathalyzer. Easier-to-use and more accurate than the Drunkometer, the Breathalyzer was the first practical device and scientific test available to police officers to establish whether someone had too much to drink. A person would blow into the Breathalyzer and it would gauge the proportion of alcohol vapors in the exhaled breath, which reflected the level of alcohol in the blood.

Drunk-O-Meter

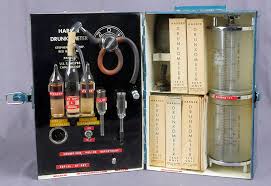

The two what appear to be glass beakers stack on top on of another in the right hand side of this picture are called "Gasometers" Kinda reminds me of how everything at McDonalds is called a Mc something or other.. with Dr. Harger everything was an, "-o-meter" or "ometer" Drunk-o-meter or Drunkometer, Gas-o-meter or Gasometer. Anyway, we are on the lookout for a Gasometer to add to our Drunkometer for the Museum-o-meter or museumometer. So if you happen to come across one in your travels, or someone that can duplicate one for display purposes. Please let us know or send them our way.

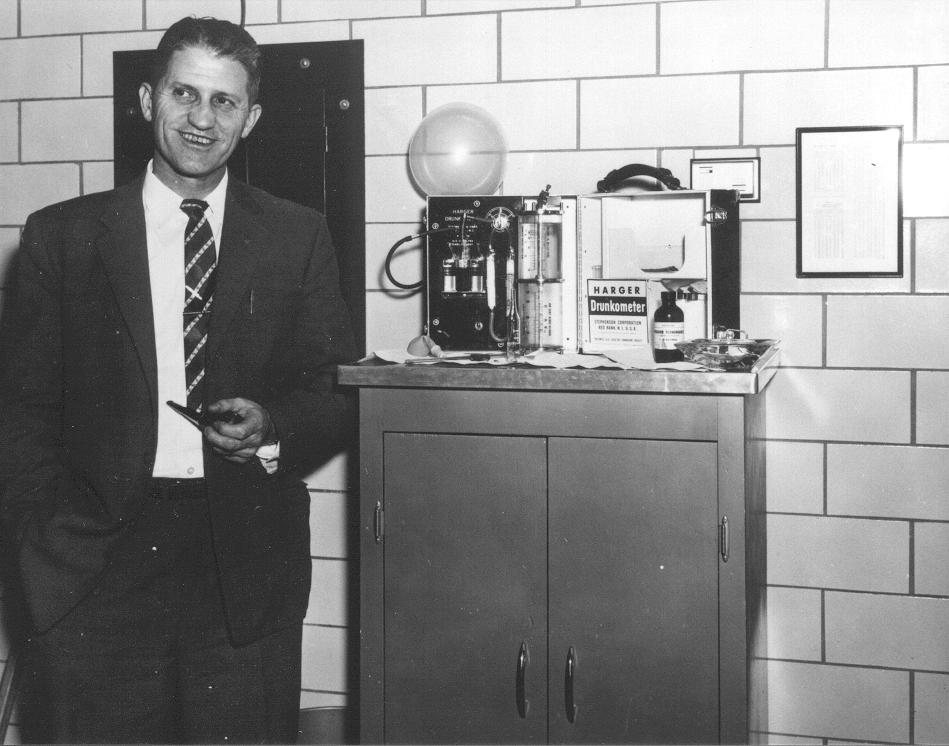

Drunkometer

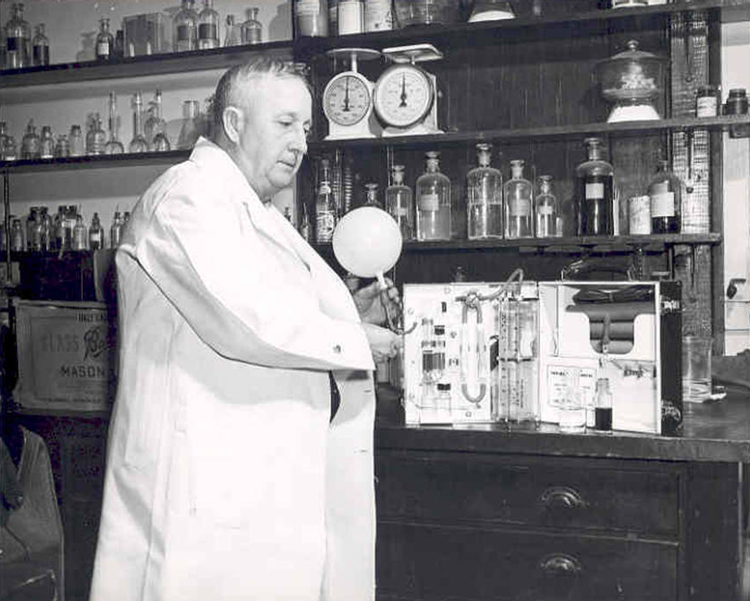

Dr. Rolla N. Harger

Dr. Rolla N. Harger, invented the Drunkometer in 1931 to test intoxicated drivers. Dr. Harger was a professor emeritus of biochemistry and toxicology at Indiana University and a consultant on toxicology to the university's School of Medicine since. The Drunkometer, which used a balloon that was inflated by persons suspected of having been drinking before or while driving. This became was the first practical breath test to measure whether a driver was intoxicated, or as he and the bulk of our country call it, Drunk. After all, it is called a Drunk-o-meter, not an Intoxicate-o-meter. The device was patented in 1936. It would become replaced in the early 1960's by the more streamlined, less science lab looking Breathalyzer.

In 1938 Dr. Harger was one of five members on a subcommittee of the National Safety Council that drafted a model act to legalize the use of evidence from chemical tests for intoxication and to set limits of body alcohol concentration for motorists.

The act was incorporated into drunken driving laws nationwide. Dr. Harger was chairman of the Indiana University School of Medicine's department of biochemistry and pharmacology from 1933 to 1956 and worked as a professor of biochemistry and toxicology from 1922 to 1960.

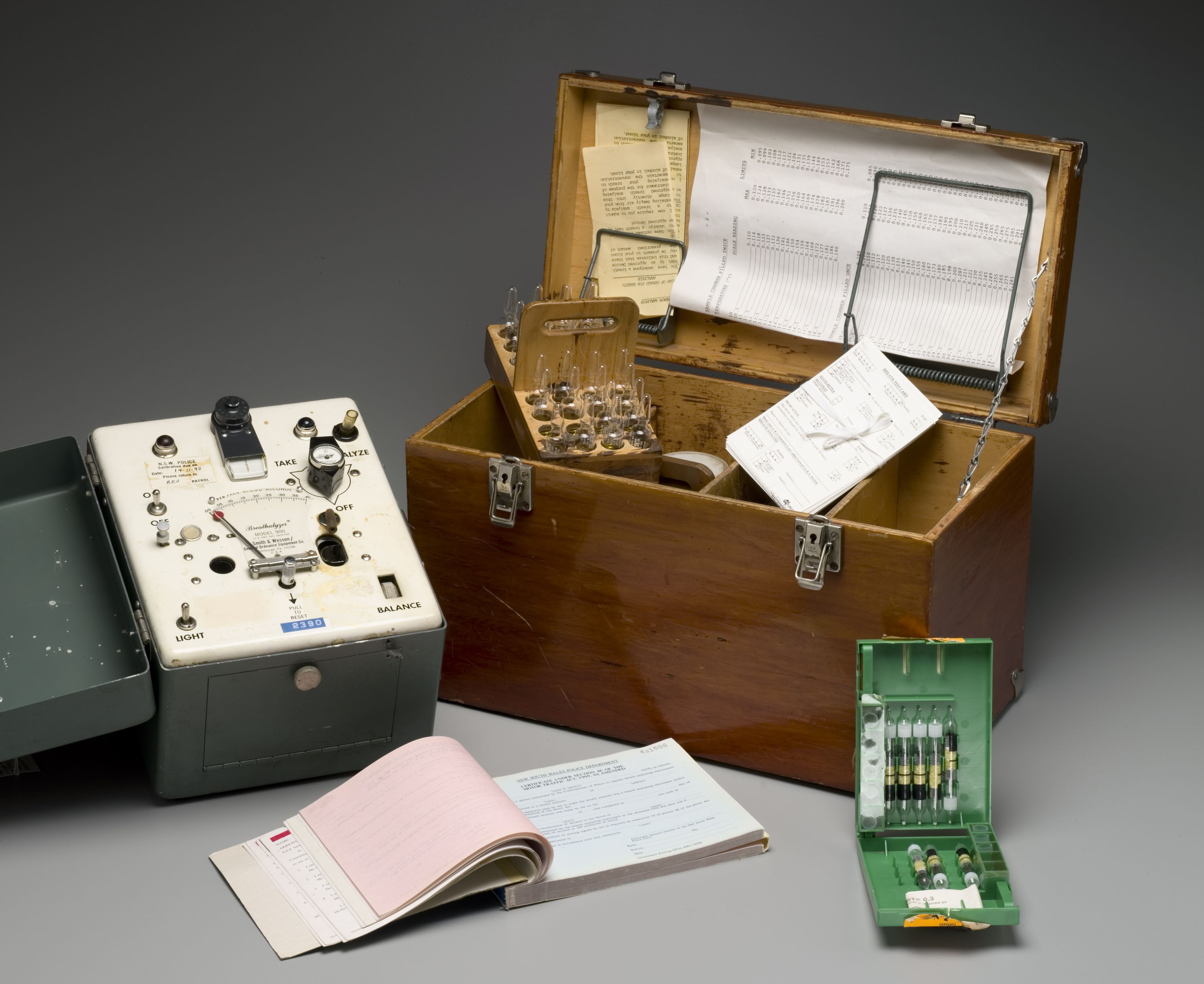

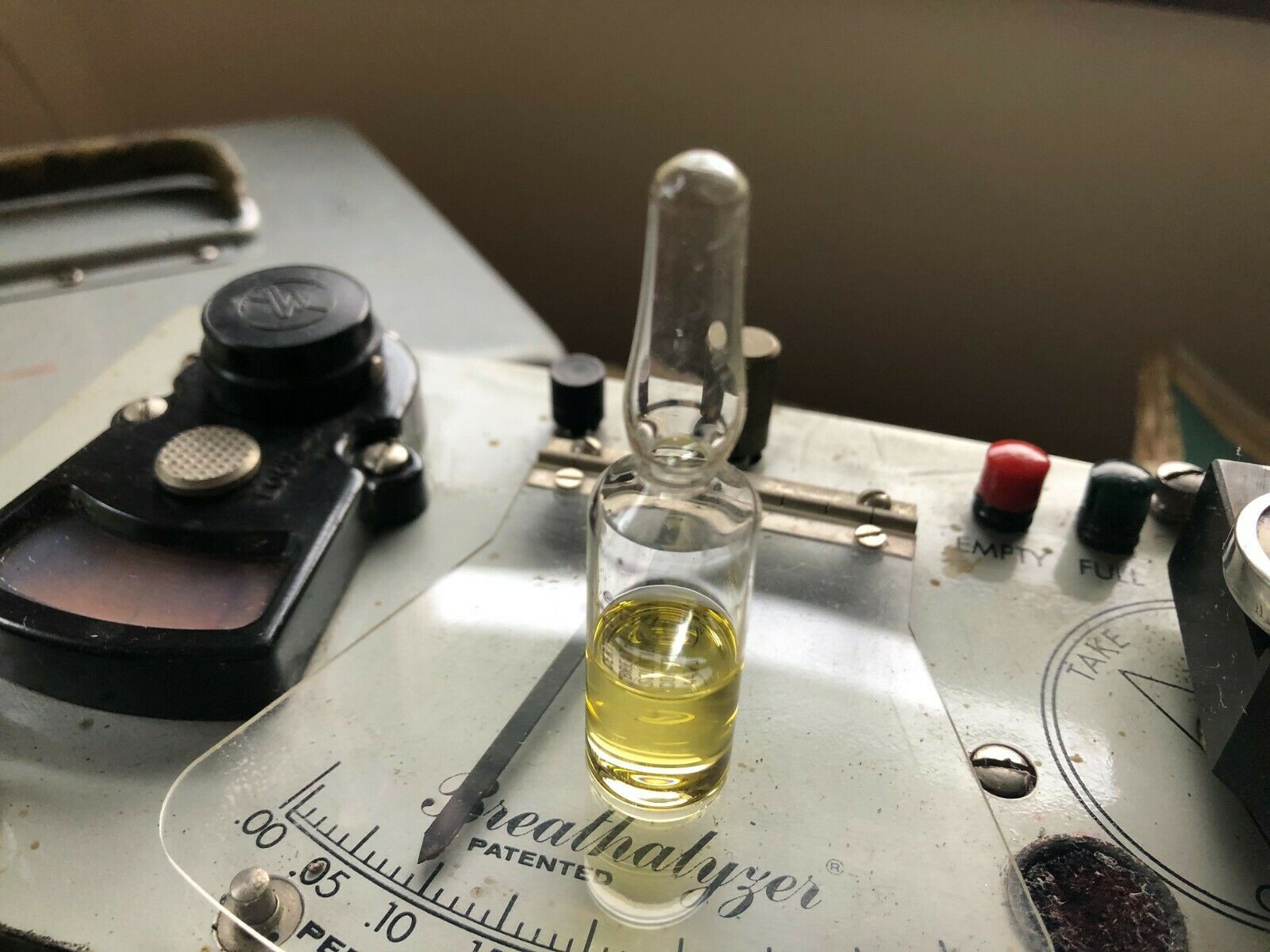

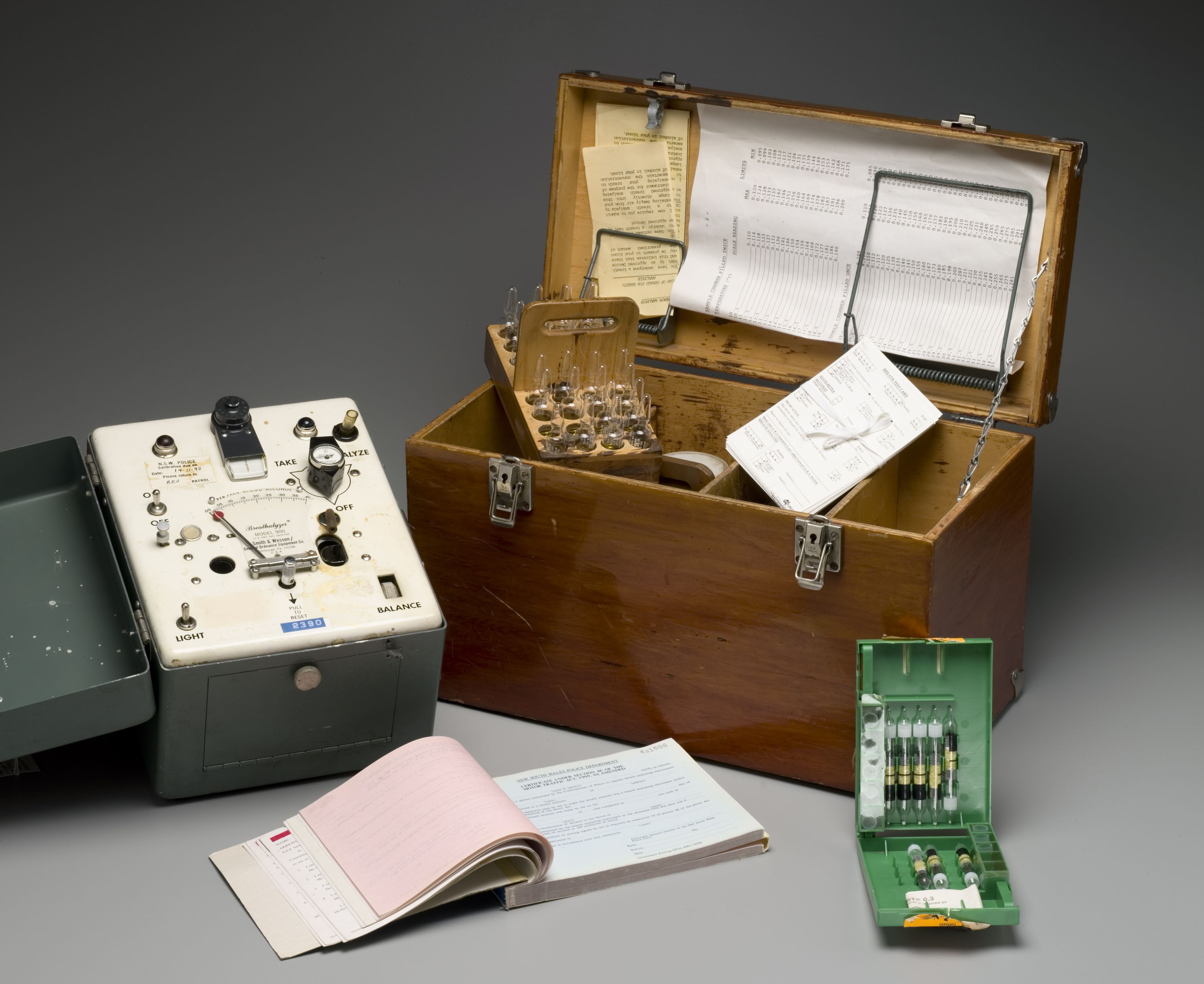

Breathalyzer

Model 900 or 900A

Despite the invention of the Breathalyzer and other developments, it was not until the late 1970s and early 1980s that public awareness about the dangers of drinking and driving increased and lawmakers and police officers began to get tougher on offenders. In 1980, a Californian named Candy Lightner founded Mothers Against Drunk Driving, or MADD, after her 13-year-old daughter Cari was killed by a drunk driver while walking home from a school carnival. The driver had three previous drunk-driving convictions and was out on bail from a hit-and-run arrest two days earlier. Lightner and MADD were instrumental in helping to change attitudes about drunk driving and pushed for legislation that increased the penalties for driving under the influence of alcohol and/or drugs. MADD also helped get the minimum drinking age raised in many states. Today, the legal drinking age is 21 everywhere in the United States and convicted drunk drivers face everything from jail time and fines to the loss of their driver's licenses and increased car insurance rates. Some drunk drivers are ordered to have ignition interlock devices installed in their vehicles. These devices require a driver to breathe into a sensor attached to the dashboard; the car won't start if the driver's blood alcohol concentration is above a certain limit.

Dr. Rolla Neil Harger

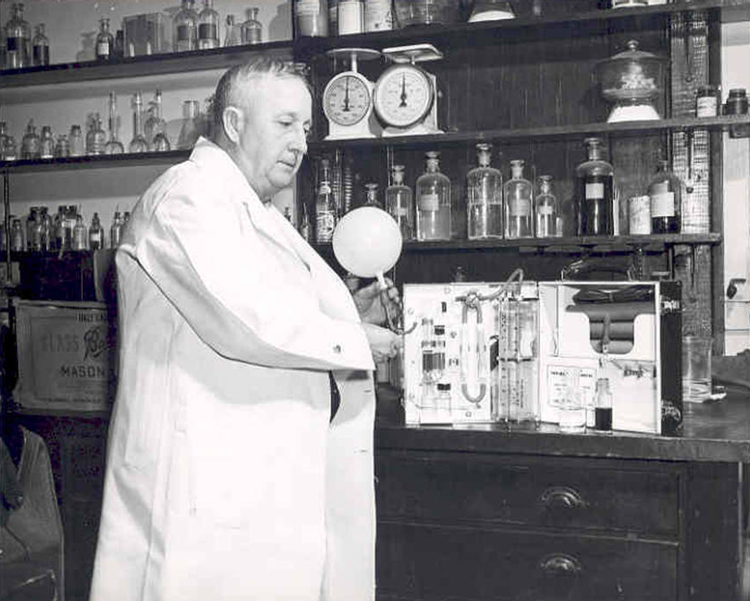

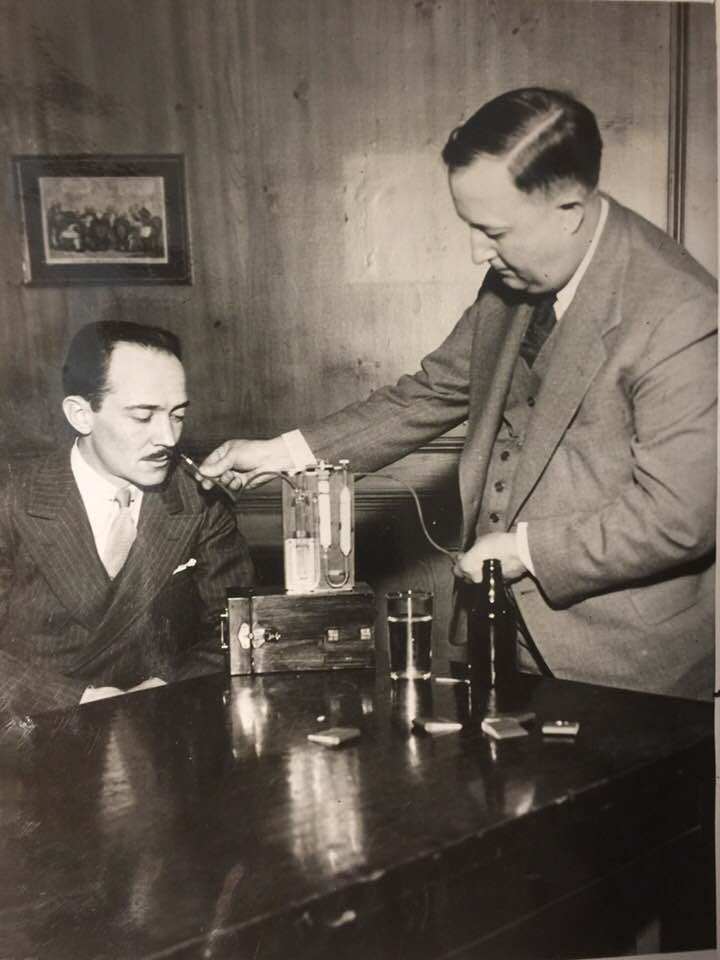

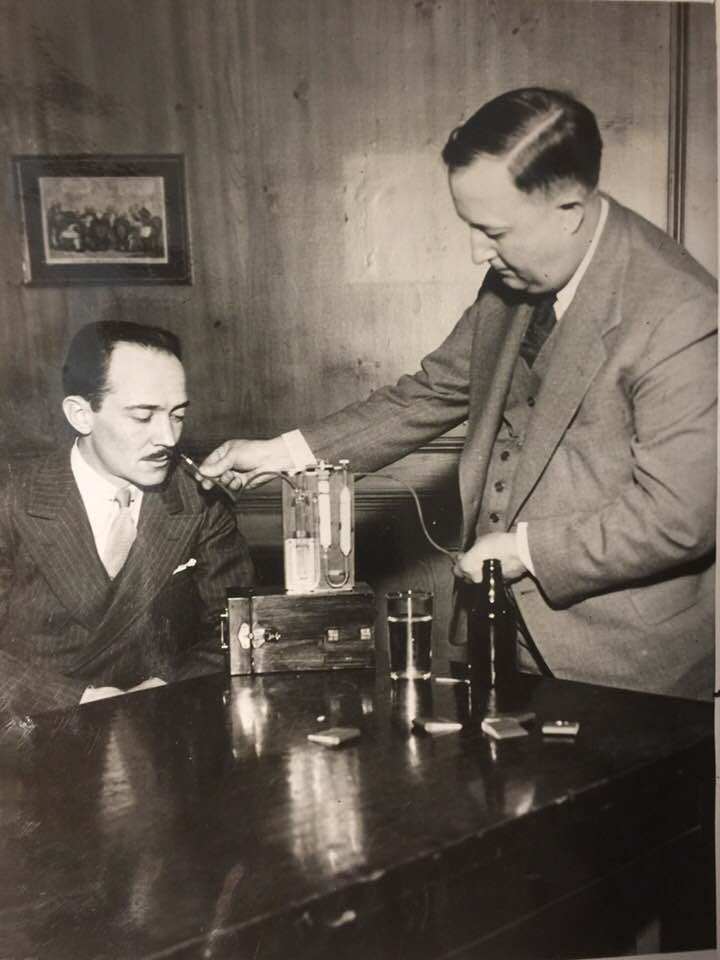

Mechanical Smeller

Drunkometer

circa 1937 Chicago Times

13 May 1937

Tells How Drunk You Are

Dr. R. A. Harger, Prof. of biochemistry and toxicology at Indiana University, using Mr. Kirk Kregan as a subject in a demonstration of his “Mechanical Smeller” at the Midwest safety conference in Chicago. It records the amount of alcohol on the breath, given index to the amount that is in the breather’s body. It was suggested for use by police on auto drivers suspected of intoxication. As it gives a reading that is much more certain than mere suspicion on the part of the policeman and tells the degree of intoxication.

Rolla Neil Harger (January 14, 1890 – August 8, 1983) invented an early breathalyzer, called the Drunkometer to test for driving under the influence in 1931 and he was awarded the patent in 1936. He was biochemistry and pharmacology department chairman of the Indiana University School of Medicine from 1933 to 1956 and worked as a professor in the department of biochemistry and toxicology from 1922 to 1960.

Harger was born on January 14, 1890, in Nebraska or in Decatur County, Kansas. He graduated from Yale University in 1922 and was hired as an assistant professor at Indiana University School of Medicine in the newly formed department of biochemistry and pharmacology.

In 1931 invented the Drunkometer to test for driving under the influence. In 1938 he was one of the five people chosen to be on the subcommittee of the National Safety Council that drafted the model legislation that set the blood alcohol content for driving under the influence.

He died on August 8, 1983

31 Dec. 1938

First “Drunkometer”

Thanks to the end of Prohibition and a boom in car sales, drunk driving had become a fast-growing problem in America in the 1930s. But on this New Year’s Eve, police in Indianapolis, Indiana went out armed with a new weapon to fight against people who had gotten behind the wheel after having too much to drink.

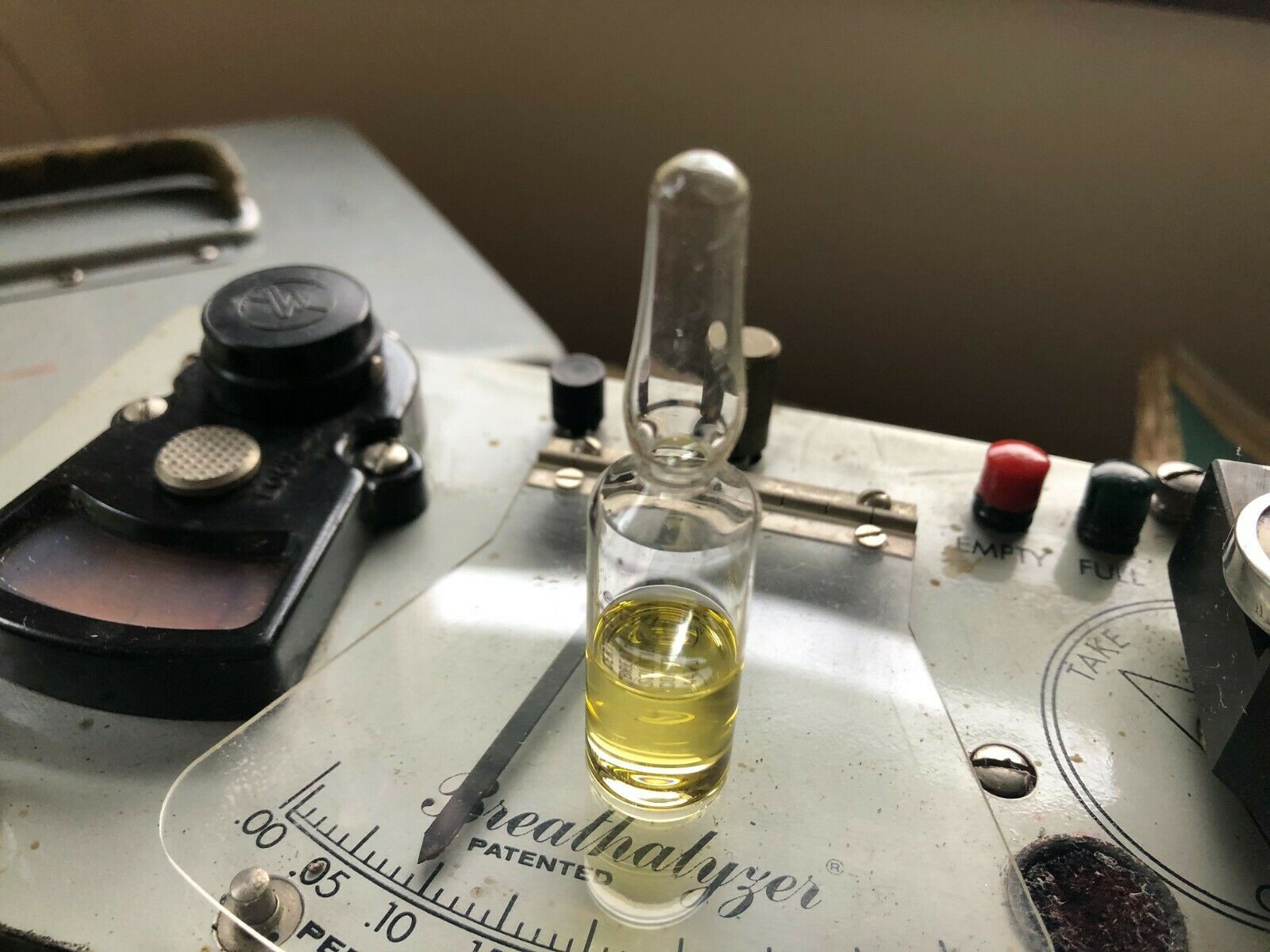

It’s a contraption called a “Drunkometer” and it’s the invention of an Indiana University chemist named Rolla Harger. He had been working on the device since the early 1930s and had patented it two years earlier. The concept behind the Drunkometer was pretty basic. Drivers suspected of being drunk were asked to breathe into a rubber balloon, which was attached to a tube of purple liquid—a weak solution of potassium permanganate in sulphuric acid.

If there was alcohol on their breath, the chemical solution changed color–the darker it got, the more alcohol they had in their system. From the shade of the liquid, the cops could use a simple equation to estimate the alcohol level in a person’s bloodstream. Previously, the only way police could check a driver’s alcohol level was to get a blood or urine sample; Neither was a very practical option on the roadside. While the Drunkometer looked a bit like a mini-chemistry set, it was portable, able to fit into a small suitcase.

Harger made the device as simple as possible so that judges and juries would understand how it worked and police officers could easily be trained to use it. He also made the Drunkometer hard to beat. Experiments showed that no illness affected the result and that nothing a person might eat - garlic, cloves, strong onions - would make any difference. Once police started using it, the Drunkometer was found to have another advantage. A dramatic change in the color of the liquid could often make people admit how much they had drunk.

Sometimes Harger would ride along with the police to see how his invention was being used. What he discovered was that a lot more people were driving drunk than he ever imagined.

The Drunk-O-Meter was used by police departments all over the country until the 1950s when it was replaced by the breathalyzer, invented by another Indiana University professor, Robert Borkenstein. The breathalyzer is a much smaller and more sophisticated device that uses infrared spectroscopy to measure blood alcohol levels.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the average drunk driver has driven drunk 80 times before his first arrest.

Model 900A

Model 900A

Stevenson Breathalyzer

Evolution of the Breathalyzer

The Breathalyzer, as created by Borkenstein, continued to be updated with later models, including Models 900, 900A, 900B, and the Model 2000 described as microprocessor-controlled and using infrared absorption to measure alcohol. The Model 2000 was never marketed but made it possible for Borkenstein to help make a prototype for a similar machine which became the precursor to the breath testing devices called the BAC Verifier and later the BAC Datamaster.

All in all, between 1955 and 1999, more than 30,000 of Borkenstein’s various Breathalyzer models were produced and sold. They were used in almost every U. S. state as well as all provinces of Canada and in Australia where it became the standard breath-testing instrument for years. In Canada, when legislation was enacted regarding DUI law, it was called the “Breathalyzer law.”

The Breathalyzer impacted more than just law enforcement but was used as well in research studies into the effects of alcohol on driving in both the U. S. and Canada. It undoubtedly played an important role in the DUI legislation which prescribed specific blood alcohol concentration limits for drivers in all states as well as in Canada. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration put the Breathalyzer on its 1974 Approved Products Lists as one of the first of its kind.

The “Breathalyzer” Today

Since Borkenstein’s original Breathalyzer, modern technology has advanced this machine. Today there are personal as well as professional breathalyzers and various types of devices based on different technologies. One of these is the electrochemical fuel cell Breathalyzer. The Alcosensor III and IV are fuel-cell devices which use an electrode system. Through a chemical reaction which occurs on the electrode system surface, an electrical current is created. This electrical current is produced by the alcohol on a person’s breath which will result in a digital readout or some other indicator.

These types of devices are small and handheld, thus useful to law enforcement. They are known for their accuracy but are expensive to manufacture.

Another type of modern Breathalyzer is the infrared optical sensor device, the latest version in what Borkenstein started with his Model 2000 Breathalyzer. An Intoxilyzer is an example of this type of device. The technology it uses is called infrared spectroscopy, which pinpoints molecules according to the way they absorb light. When ethanol in the breath absorbs the light, an electrical impulse is created which measures this which is then processed by a microprocessor into a BAC level. These types of devices are generally too large to be used as handheld devices.

Dual sensor breathalyzers are another type of device which use both infrared and electrochemical sensors combined into one device to give a very accurate measure of blood alcohol concentration.

Personal Breathalyzers

Finally, semiconductor breathalyzers are now available for private use by individuals. These small, handheld devices can be found online and in convenience stores; they are inexpensive because they are cheap to make. They also produce an electrical current when alcohol comes into contact with the surface of the semiconductor. These portable devices are not, however, as reliable as the more sophisticated types mentioned above used by law enforcement. That is because they vary in quality and can be affected by the atmosphere in which they are used. Their use is also dependent on correct operation.

Substances in the air around personal breathalyzers, such as cigarette smoke, carbon monoxide, and other fumes and gases can influence their readings as well as fluctuations in the humidity and temperature of the air. Changes in the patterns of the user’s breath flow can also influence readings as well as residual mouth alcohol. Artificially high as well as artificially low readings may result when used by consumers who do not fully understand how these factors can impinge on results. A further caution lies in the fact that the test results of a device used by law enforcement are the defining results which will be used in court as evidence for a DUI conviction. If used correctly, personal breathalyzers may be beneficial to responsible drivers concerning their driving ability but they should not be totally relied up to prevent a drunk driving conviction.

The Use of Breathalyzers

The Breathalyzer device has come a long way from its inception in the early 1950s. Accepted as a standard basis for most DUI convictions, it has led to changing laws concerning drunk driving restrictions throughout the U.S. In connection with DUI convictions, it has led to the ignition interlock device, a type of Breathalyzer wired into a convicted driver’s vehicle’s ignition which prevents it from starting if the user fails the breath test. The installation of this device is becoming increasingly popular as a court-ordered action for mostly repeat offenders in many states.

Beyond this, however, the Breathalyzer can now be used by more than just law enforcement as it finds its way into such areas as the workplace, in research studies, medical clinics, alcohol treatment programs, probation programs, halfway houses, and more. As technology advances, the Breathalyzer will likely become even more refined and widely applied, although its continued use now is assured.

Model 900A

Model 900A

Stevenson Breathalyzer

15 Oct 1959

Policeman's Lot Happy One Testing Drunkenness Gauge

ALBERT SEHLSTEDT JR - pg. 40

STEADY, STEADY - These police officers are taking tests to demonstrate effects on their reflexes of too much alcohol. Sgt. Lemuel Porter reaches for coins and walks a straight line, and Sgt. Preston Rowland tries to touch the tip of his nose.

Policeman's Lot Happy One Testing Drunkenness Gauge

When policemen have too much to drink, they giggle, perform the simplest tasks with. Heavy-handed concentration and, in general, act the same way other people do. This may seem humorous to the average citizen but all that follows will be bad news for motorists not averse to getting behind the wheels of their cars with a few on board. Yesterday, three policemen at the State Police Headquarters in Pikesville did have a bit too much, but it was to demonstrate a new device that will make it much more difficult for drinking drivers to escape convictions in the courts.

Plastic Tube Used

The device is called a Breathalyzer. It analyzes the alcoholic content in the blood simply by having a driver blow into a plastic tube. The Breathalyzer will be used by State Police and Baltimore City Police after the first of the year.

Approximately 100 policemen from various Maryland jurisdictions assembled at Pikeville yesterday to learn how to use the machine. Naturally. somebody had to do a little drinking before the demonstration could be made. Three volunteers were Lt. Hugh Kavanaugh, Sgt. Preston Rowland and Sgt. Lemuel Porter.

Lieutenant Kavanaugh had 13 ounces of 86-proof whiskey. Sgt Rowland eight bottles of beer, and Sgt Porter 10 ounces of whiskey. The Breathalyzer showed that there was .163 percent of alcohol in Lieutenant Kavanaugh’s blood; .13 percent in Sgt Rowland’s blood and .148 recent in Sgt Porter’s. Had the test been real Lieutenant Kavanaugh would have stood a good chance of going to jail, and the two sergeants would have had considerable explaining to do before a magistrate or judge. According to standards established by the American Medical Association and the National Safety Council, anybody with .15 percent of alcohol in his blood is unfit to drive.

Figure Called Liberal

Hugh G. Boyd, a representative of the Stephenson Corporation of Red Bank, New Jersey, the company selling the Breathalyzers to our State and City Police at $650 each, told the two agencies yesterday that the .15 percent figure is a liberal number, a number that gives the driver a break.

People with .05 percent are generally not considered under the influence of alcohol. Person’s falling between these two figures are in a sort of a no-man’s land where other evidence of drunkenness, or sobriety, must supplement the machine’s findings’

Other Evidence Needed

Indeed, the findings of the Breathalyzer will not be used exclusively by police in prosecuting a case in court. Other evidence, such as observation of the driver while they walk a chalk line or lean over to pick up some coins from the ground, as the three officers did (or attempted to do) yesterday will also be taken into consideration

Col. Carey. Jarman, Superintendent of the State Police, emphasized that the new device is “no panacea” for the drinking-driving problem. “However,” Colonel Jarman said. "it is a distinct help. It is a tool in the hands of enforcement agencies.” Clayton A. Dietrich, an assistant attorney general of Maryland, said he considered the Breathalyzer a “double-edged sword” for the prosecution.

Mr. Dietrich said the device could corroborate the policeman’s testimony and also undermine the position of the defense in drinking-driver cases

Alco-Sensor III

A law enforcement grade Breathalyzer, specifically an Alco-Sensor IV - A breathalyzer or breathalyzer (a portmanteau of breath and analyzer/ analyzer) is a device for estimating blood alcohol content (BAC) from a breath sample. The breathalyzer is the brand name (a genericized trademark) for the instrument that tests the alcohol level developed by inventor Robert Frank Borkenstein. It was registered as a trademark on May 13, 1954, but many people use the term to refer to any generic device for estimating blood alcohol content.

Widely used, the Alco-Sensor III (ASIII) is a pocket-sized, handheld breath alcohol tester. This NHTSA approved Evidential Breath Alcohol Testing Device provides a simple, accurate and economical method of determining a subject’s breath alcohol concentration.

Features:

The Alco-Sensor III offers last test recall, mouthpiece ejector, internal temperature sensor with software controlled temperature compensation and automated calibration. The unit has a large, bright, three-digit display that captures and holds the results without the need to press and hold the READ button.

Alco-Sensor III Law Enforcement

Trusted by Law Enforcement agencies worldwide, the Alco-Sensor III evidential breathalyzer is widely used for the following reasons:

- Approved by the U.S. DOT as an evidential breath testing device

- Approved for use by law enforcement agencies in almost every state as a PBT (Preliminary Breath Tester)

- Evidential Accuracy to +/- .005 BAC.

- Displays breath alcohol results to three decimal places

- Fuel cell sensor detects and reads alcohol only

- Easy two-button operation

- The display prompts the operator through a test sequence, greatly reducing operator error

- When pressed, the READ button captures a breath sample for analysis

- Displays test results within seconds

- Able to re-display results by pressing the READ button a second time

- Mouthpiece ejector button

- GSA Pricing available for Federal Agencies

- Secure Calibration Procedure eliminates accidental tampering or unauthorized calibration adjustments

Alco-Sensor III Mouthpiece

The standard Alco-Sensor and Alco-Sensor III mouthpiece. With no restriction, back pressure is minimal and samples provided produce consistent and accurate results. All Intoximeters mouthpieces come individually wrapped for maximum hygiene.

Breathalyzer

HISTORY - A 1927 paper produced by Emil Bogen, who collected air in a football bladder and then tested this air for traces of alcohol, discovered that the alcohol content of 2 liters of expired air was a little greater than that of 1 cc of urine. However, research into the possibilities of using breath to test for alcohol in a person's body dates as far back as 1874, when Francis E. Anstie made the observation that small amounts of alcohol were excreted in breath.

Also, in 1927 a Chicago chemist, William Duncan McNally, invented a breathalyzer in which the breath moving through chemicals in water would change color. One use for his invention was for housewives to test whether their husbands had been drinking.

In late 1927, in a case in Marlborough, England, a Dr. Gorsky, Police Surgeon, asked a suspect to inflate a football bladder with his breath. Since the 2 liters of the man's breath contained 1.5 ml of ethanol,[dubious – discuss] Dr. Gorsky testified before the court that the defendant was "50% drunk".

In 1931 the first practical roadside breath-testing device was the Drunkometer developed by Rolla Neil Harger of the Indiana University School of Medicine. The Drunkometer collected a motorist's breath sample directly into a balloon inside the machine. The breath sample was then pumped through an acidified potassium permanganate solution. If there was alcohol in the breath sample, the solution changed color. The greater the color change, the more alcohol there was present in the breath. The Drunkometer was manufactured and sold by Stephenson Corporation of Red Bank, New Jersey.

In 1954 Robert Frank Borkenstein (1912–2002) was a captain with the Indiana State Police and later a professor at Indiana University Bloomington. His Breathalyzer used chemical oxidation and photometry to determine alcohol concentrations. Subsequent breath analyzers have converted primarily to infrared spectroscopy, though this method is subject to invalid results depending on ambient air temperature, the temperature of the device, and the body temperature of the subject, depending on the specificity of the readings and how they correlate with one's BAC measured via a voluntary blood draw. The invention of the Breathalyzer provided law enforcement with an orally-invasive test providing immediate results to determine an individual's breath alcohol concentration at the time of testing, based on, according to this article, consistently faulty samples.

In 1967 in Britain, Bill Ducie and Tom Parry Jones developed and marketed the first electronic breathalyzer. They established Lion Laboratories in Cardiff. Ducie was a chartered electrical engineer, and Tom Parry Jones was a lecturer at UWIST. The Road Safety Act 1967 introduced the first legally enforceable maximum blood alcohol level for drivers in the UK, above which it became an offense to be in charge of a motor vehicle; and introduced the roadside breathalyzer, made available to police forces across the country. In 1979, Lion Laboratories' version of the breathalyzer, known as the Alcolyzer and incorporating crystal-filled tubes that changed color above a certain level of alcohol in the breath, was approved for police use. Lion Laboratories won the Queen's Award for Technological Achievement for the product in 1980, and it began to be marketed worldwide. The Alcolyzer was superseded by the Lion Intoximeter 3000 in 1983, and later by the Lion Alcolmeter and Lion Intoxilyzer. These later models used a fuel cell alcohol sensor rather than crystals, providing a more reliable curbside test and removing the need for blood or urine samples to be taken at a police station. In 1991, Lion Laboratories was sold to the American company MPD, Inc.

CHEMISTRY - When the user exhales into a breath analyzer, any ethanol present in their breath is oxidized to acetic acid at the anode:

CH3CH2OH(g) + H2O(l) → CH3CO2H(l) + 4H+(aq) + 4e−

At the cathode, atmospheric oxygen is reduced:

O2(g) + 4H+(aq) + 4e− → 2H2O(l)

The overall reaction is the oxidation of ethanol to acetic acid and water.

CH3CH2OH(l) + O2(g) → CH3COOH(aq) + H2O(l)

The electric current produced by this reaction is measured by a microcontroller and displayed as an approximation of overall blood alcohol content (BAC) by the Alcosensor.

LAW ENFORCEMENT - Breath analyzers do not directly measure blood alcohol content or concentration, which requires the analysis of a blood sample. Instead, they estimate BAC indirectly by measuring the amount of alcohol in one's breath. In general, two types of breathalyzer are used. Small hand-held breathalyzers are not reliable enough to provide evidence in court but reliable enough to justify an arrest. Larger breathalyzer devices found in police stations can then be used to produce court evidence.

Two breathalyzer technologies are most prevalent. Desktop analyzers generally use infrared spectrophotometer technology, electrochemical fuel cell technology, or a combination of the two. Hand-held field testing devices are generally based on electrochemical platinum fuel cell analysis and, depending upon jurisdiction, may be used by officers in the field as a form of "field sobriety test" commonly called PBT (preliminary breath test) or PAS (preliminary alcohol screening) or as evidential devices in POA (point of arrest) testing.

In Canada, a preliminary non-evidentiary screening device can be approved by Parliament as an approved screening device, and an evidentiary breath instrument can be similarly designated as an approved instrument. The US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration maintains a Conforming Products List of breath alcohol devices approved for evidentiary use, as well as for preliminary screening use. In order to demand a person produce a breathalyzer sample, an officer must have "reasonable suspicion" that the person drove with more than 80 mg alcohol per 100 mL of blood. The demand must be within three hours of driving. Any driver that refuses can be charged under s.254 of the Criminal Code. Most states, including California and Michigan, have implied consent laws, which means that by applying for a driver's license, drivers are agreeing to take any breathalyzer test under suspicion of a DUI. However, if the officer lacks reasonable suspicion and the person refuses there is no crime since the demand was not lawful and without the breathalyzer readings there is usually not probable grounds for arrest on the above driving over 80 charges.

Standardized Field Sobriety Test

Definition: The Standardized Field Sobriety Test (SFST) is a battery of 3 tests performed during a traffic stop in order to determine if a driver is impaired. The 3 tests that make up the SFST are the horizontal gaze nystagmus (HGN), the walk-and-turn, and the one-leg stand tests. Developed in the 1970s, these tests are scientifically validated, and are admissible as evidence in court in a majority of states.

Executive Summary: According to researchers, officers trained to conduct SFSTs correctly identified alcohol-impaired drivers over 90% of the time using the results of SFSTs (Burns and Anderson 1995; Stuster and Burns 1998). The SFST consists of three tests administered and evaluated during a traffic stop to determine impairment and probable cause for arrest. The HGN test is performed to observe whether the driver’s eyes involuntarily jerk as a stimulus is moved side to side. Both the walk-and-turn and one-leg stand tests are “divided attention” tests that are easily performed by most sober drivers. They require a subject to listen and follow instructions while performing simple physical movements. Impaired persons have difficulty with tasks requiring their attention be divided between simple mental and physical tasks.

More Detail: The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) defines the three parts of the SFST as follows (see NHTSA Highway Safety Desk Book):

The horizontal gaze nystagmus (HGN) test: Horizontal gaze nystagmus is an involuntary jerking of the eyeball which occurs as the eyes gaze to the side. Under normal circumstances, nystagmus occurs when the eyes are rotated at high peripheral angles. However, when a person is impaired by alcohol, nystagmus is exaggerated and may occur at lesser angles. An alcohol-impaired person will also often have difficulty smoothly tracking a moving object. In the HGN test, the officer observes the eyes of a suspect as the suspect follows a slowly moving object such as a pen or small flashlight, horizontally with his eyes. The examiner looks for three indicators of impairment in each eye: if the eye cannot follow a moving object smoothly, if jerking is distinct and sustained nystagmus when the eye is at maximum deviation, or if the angle of onset of jerking is prior to 45 degrees of center. The subject is likely to have a BAC of 0.08 or greater if, between the two eyes, four or more clues appear. A 1998 validation study found that this test allows proper classification of approximately 88 percent of subjects. HGN may also indicate consumption of seizure medications, phencyclidine, a variety of inhalants, barbiturates, and other depressants.

In the walk-and-turn test, the subject is directed to take nine steps, touching heel-to-toe, along with a straight line. After taking the steps, the suspect must turn on one foot and return in the same manner in the opposite direction. The examiner looks for eight indicators of impairment: if the suspect cannot keep balance while listening to the instructions, begins before the instructions are finished, stops while walking to regain balance, does not touch heel-to-toe, uses arms to balance, steps off the line, takes an incorrect number of steps, or makes an improper turn. A 1998 validation study found that 79 percent of individuals who exhibit two or more indicators in the performance of the test will have a BAC of 0.08 or greater.

In the one-leg stand test, the subject is instructed to stand with one foot approximately six inches off the ground and count aloud by ones beginning with one thousand (one-thousand-one, one thousand-two, etc.) until told to put the foot down. The officer times the subject for 30 seconds. The officer looks for four indicators of impairment including swaying while balancing, using arms to balance, hoping to maintain balance, and putting the foot down. A 1998 validation study found that 83 percent of individuals who exhibit two or more such indicators in the performance of the test will have a BAC of 0.10 or greater.

There are many factors that might render a person unable to successfully complete one or more of the SFSTs. For instance, regarding the HGN test, the person asked to consent to such a test might be suffering from an eye disease or condition that affects his/her ability to see and consequently confound the test and results. Age, injury or disease could also affect the ability of a person to perform the one-leg stand test or the walk and turn test. As a general rule, an officer should ask the DUI suspect whether they can give any reason why they cannot perform the test and their answer should be carefully noted in the officer’s report. Other disabilities, such as deafness, should be taken into consideration and noted as well.

Admissibility of Standardized Field Sobriety Test Results

In 1981 NHTSA promulgated a federal standard for field sobriety testing procedures. States are not required to adhere to this federal standard. Although some states do not employ the exact procedures, others replicate NHTSA procedures as closely as possible. In Ohio v. Homan, 732 N.E.2d 952 (Ohio, 2000), Ohio became the only state where courts ruled that evidence is “inherently unreliable” and inadmissible when gathered from field sobriety tests that deviate from NHTSA standards. However, this “strict compliance” standard has since softened to a “substantial compliance” standard, as confirmed by the Ohio State Supreme Court in Ohio v. Boczar, 863 N.E.2d 155, 160 (Ohio, 2007).

Furthermore, according to NHTSA, courts in several states have reviewed the admissibility of field sobriety tests and have held that deviations from the administration of simple dexterity tests (one-leg stand and walk-and-turn tests) should not result in the suppression of test results. However, admissibility of the HGN test may be treated differently due to its “scientific nature.” For this reason, HGN results are vulnerable to challenge and likely to be excluded by the court if the test was not administered in strict compliance with established protocols. Appellate courts generally require that, before an opinion can be expressed by an officer who administered an HGN test, the officer must be qualified as an expert or skilled witness for the purpose of administering the test as well as expressing an opinion as to the results. For example see Robinson v. State 982 So.2d 1260, 1261 Fla. App. 1 Dist., 2008.

We have come along way since the days of these tests, the handheld tests over the Drunk-O-Meter and Breathalyzer are accurate, they save time, money and ultimately lives. Many of them still require some probably cause more than swerving while driving, or a scent of alcohol coming from the vehicle being driven, there were a series of roadside sobriety test. The one most recognized is in the picture below, walking a straight line.

Today reporting a drunk driver can be easier than ever before, but doing so has to be done with as much caution and care as possible. As with the invention of the cellphone, we have created a device that can be as reckless as drinking while driving. So unless you have someone in the car with you to call a potential drunk driver in, you should either wait until you reach a red light or stop sign intersection, or pull over to the side of the road before making that very important call. Once you have made the call, be prepared to give the operator with a tag number (or partial tag) and direction of travel or flag down an officer should you see one in the area. As for remembering a tag number, if you have a poor memory, remember as much as you can, three letters three numbers.. when you call 911, before saying anything just say the number, they will get it, then give details about your reason for calling. Some jurisdictions will ask if you need, police fire or medical assistance, you can quickly say police and give your tag number, if the operator asks you can repeat the tag number and and and ask if they got it before giving your narration. I think it is important to report things like this as you might save a life. Keep in mind from time to time, the drunk driver you see driving reckless, might not be a drunk driver at all. I once followed a drunk driver throughout our neighborhood, witnessed it striking parked cars, and traffic devices, such as stop signs, one-way signs, curbs and other stationary objects. I would say my wife and followed this driver for more than 5 miles before we were able to lead police to the vehicle. Once it was stopped they found the driver was having a diabetic seizure, so aside from saving the public, you might also save the driver.

Stevenson Breathalyzer

Managing diabetes effectively requires knowledge of the condition and the steps necessary to avoid complications. Blood glucose levels that are too high or too low for prolonged periods have detrimental effects on overall health and can lead to death. A diabetic seizure is a serious complication of this disease. Patients and caregivers must know how to avoid seizures and to recognize their signs so that proper immediate assistance is provided.

According to the American Diabetes Association, a diabetic seizure can occur when you become hypoglycemic, which means blood sugar levels have dropped too low. This happens if you take too much insulin, exercise vigorously without eating properly, skip meals, drink too much alcohol or have a metabolic disease. It can also occur as a reaction to medications, such as heart medicines and those that cause the pancreas to release more insulin. Hyperglycemia, or levels of blood sugar that are too high, can also lead to a diabetic seizure.

Initial symptoms of a diabetic seizure include sweating, feeling cold or clammy, shakiness and feeling faint, sleepy or confused. Additional seizure signs are feeling anxious, muscle weakness or a loss of muscle control, loss of ability to speak clearly and changes in vision. You may hallucinate, be unaware of your surroundings, cry without control or have other unexplained emotional behaviors.

If a seizure is untreated you may become unconscious, fall and have convulsions that cause muscles to contract involuntarily, making the body move and jerk out of control; this can be mild or severe. Patients may also appear to be in a trance and unable to respond, with eyes blinking rapidly or staring into space.

The best treatment is prevention. Check blood sugar levels often and eat a proper diet. Immediate attention is needed if you do have a seizure and become unconscious. It is important to wear a medical ID bracelet specifying diabetes so that responders can provide appropriate care. The usual course of treatment is an injection of glucagon to quickly bring blood sugar levels back to normal. A diabetic seizure can be life-threatening if not treated quickly.

Donations

Donations help with web hosting, stamps and materials and the cost of keeping the website online. Thank you so much for helping BCPH.

POLICE INFORMATION

Copies of: Your Baltimore Police Department Class Photo, Pictures of our Officers, Vehicles, Equipment, Newspaper Articles relating to our department and or officers, Old Departmental Newsletters, Lookouts, Wanted Posters, and or Brochures. Information on Deceased Officers and anything that may help Preserve the History and Proud Traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to Honor the fine men and women who have served with Honor and Distinction at the Baltimore Police Department. Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. follow us on Twitter @BaltoPoliceHist or like us on Facebook or mail pics to 8138 Dundalk Ave. Baltimore Md. 21222

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll