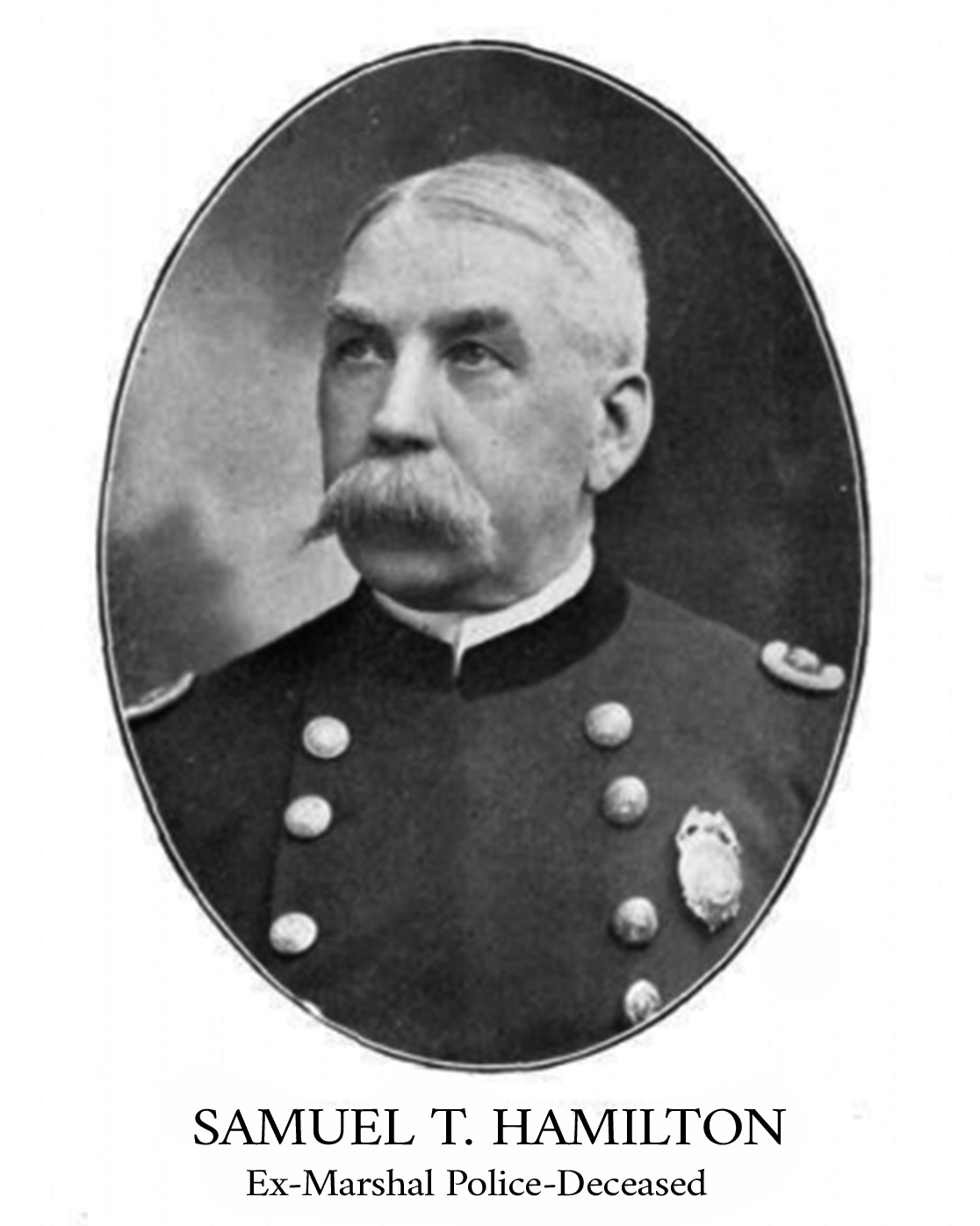

Samuel Hamilton

Marshal Samuel T. Hamilton![]()

On October 7, 1897, Capt. Samuel T. Hamilton was elected Marshal of Police to succeed Marshal Jacob Frey. Marshal Hamilton was a veteran officer of the Civil War and a man of indisputable courage and integrity.

For many years following the great civil conflict he had served on the Western frontier and took part in the unremitting campaigns against the Sioux and other Indian tribes that were constantly waging war upon the settlers and pioneers as they pushed their way toward the setting sun, building towns and railroads and trying to conquer the wilderness and its natural dwellers.

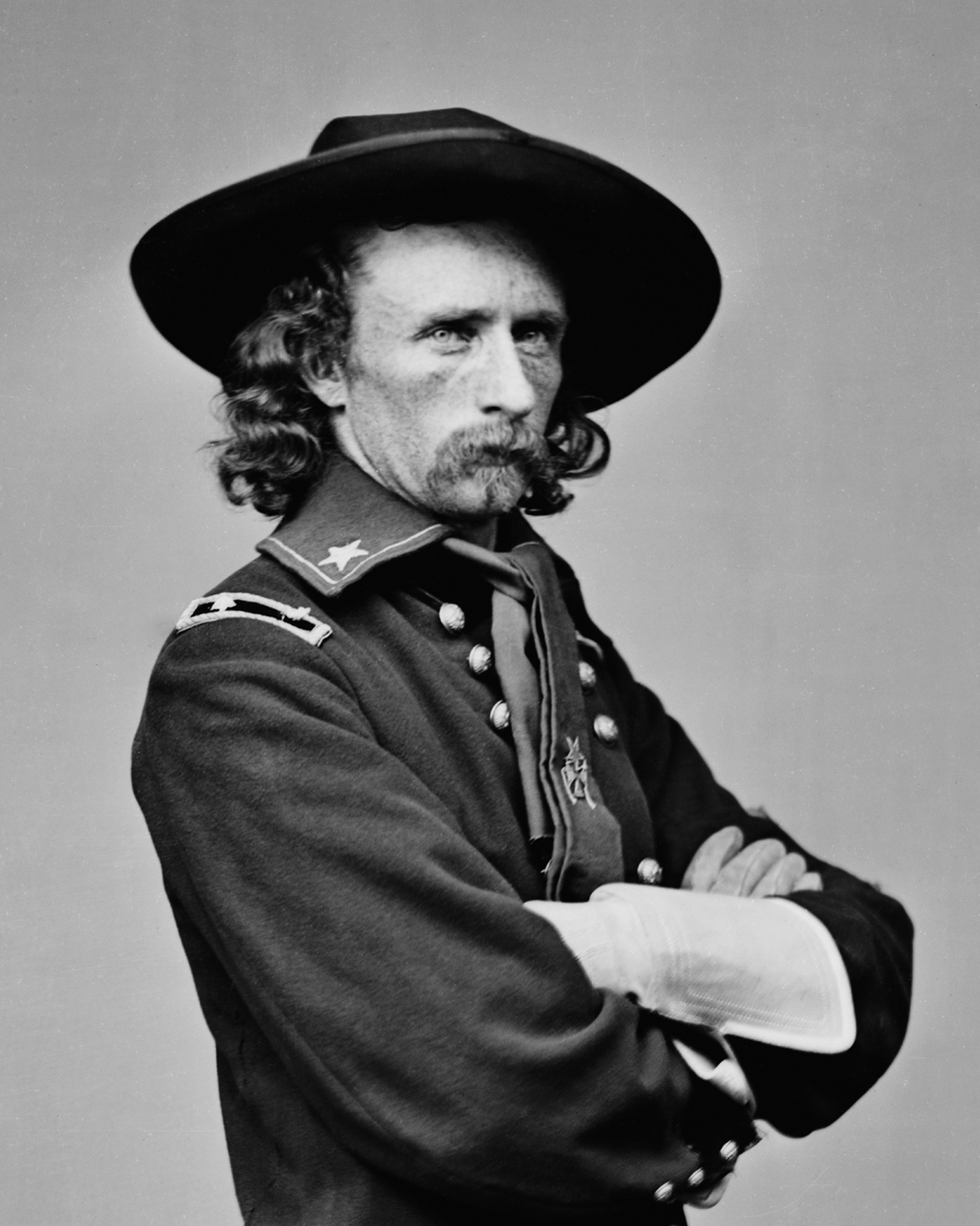

In the Sioux campaign of 1876, when Gen. George A. Custer and his command, outnumbered ten to one by the Indians in the valley of the Little Big Horn were annihilated, Captain Hamilton and his troop rode day and night in a vain effort to re-enforce Custer and his sorely pressed men.

It was on June 26, 1876, the 7th United States Cavalry rode and fought to their deaths, and on the 27 of the same month, just 1 day after the Battle at Little Big Horn, the reinforcements arrived, exhausted from their terrific ride across the country. Captain Hamilton and his troops fought through the rest of the campaign, which resulted in Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, the great Indian war chief, being driven across and into the Canadian frontier.

Marshal Hamilton brought to his office pronounced ideas of a semi-military discipline for the police, (what is called today a paramilitary organization) and it may be said that many of the military forms which were adopted under his administration have been of great service to the Department in the matter of the individual carriage and conduct of the members when on the street.

Ex-Marshal Hamilton, after ceasing his connection with the Police Department, was raised to the rank of Major in the United States Army and granted a pension commensurate with that rank. Accustomed to an active life, he requested the War Department to give him employment, and he was assigned to take charge of the army recruiting district, with headquarters in Harrisburg, Pa., where he died in 1906.

![]()

Jacob Frey served as Marshal from Oct 15, 1885 - Jul 12, 1897

Jacob Frey served as Marshal from Oct 15, 1885 - Jul 12, 1897

Gen. George A. Custer - Little Big Horn - 26 June 1876 - Crazy Horse & Sitting Bull

On 12 July 1897, the active connection of Marshal Jacob Frey with the Police Department ceased. On 7 October 1897, Capt. Samuel T. Hamilton was elected Marshal of Police to succeed Marshal Frey. Marshal Hamilton was a veteran officer of the Civil War and a man of indisputable courage and integrity. For many years following the great civil conflict he had served on the Western frontier and took part in the unremitting campaigns against the Sioux and other Indian tribes, who were constantly waging war upon the settlers and pioneers as they pushed their way toward the setting sun, building towns and railroads and trying to conquer the wilderness and its natural dwellers. In the Sioux campaign of 1876, when Gen. George A. Custer and his gallant command, outnumbered ten to one by the Indians in the valley of the Little Big Horn, were annihilated, Captain Hamilton and his troop rode day and night in a vain effort to re-enforce Custer and his sorely pressed men. It was on 26 June 1876, the Seventh United States Cavalry rode and fought to their deaths, and on 27 June, the day following, the reinforcements arrived, exhausted from their terrific ride across the country. Captain Hamilton and his troop fought through the rest of the campaign, which resulted in Sitting Bull, the great Indian war chief, being driven across the Canadian frontier. Marshal Hamilton brought to his office pronounced ideas of a semi-military discipline for the police, and it may be said that many of the military forms which were adopted under his administration have been of great service to the Department in the matter of the individual carriage and conduct of the members when on the street. Ex-Marshal Hamilton, after ceasing his connection with the Police Department, was raised to the rank of Major in the United States Army and granted a pension commensurate with that rank.

Page 45 of the Baltimore Police History Blue Book Click HERE

Capt. Samuel T. Hamilton Audio HERE

![]()

MARSHAL THOMAS F. FARNAN

Marshal Thomas F. Farnan, the present head of the Baltimore Police Department, has rounded out forty years' continuous service as a policeman. Looking back on the splendid record made by this ideal chief of a police force that is considered one of, if not the best, in the country, one is impressed with the belief that Thomas F. Farnan was born to be a policemen and that he was particularly destined to fill the responsible position he now occupies. Entering the police service on April 30, 1867, Marshal Farnan step by step climbed the ladder of promotion until, on August 8, 1902, he reached the summit and by the unanimous vote of the Board of Police Commissioners, Messrs. George M. Upshur, John T. Morris and Edward H. Fowler, was appointed Marshal of Police, to succeed Marshal S. T. Hamilton, whose commission had expired seven months before that date. From the time that Marshal Hamilton's commission expired until the date of his final promotion Deputy Marshal Farnan was to all practical purposes the Marshal of Police of the city, for he exercised all the functions of that office.

Not only this humble volume but the future histories of Baltimore City will give Thomas F. Farnan a prominent place in their pages. During his administration the great fire of February 7, 1904, swept Baltimore's great business district, laying in ruins over 70 blocks of the commercial section of the city. From the time the first alarm was sounded until three months afterward Marshal Farnan was practically on duty day and night. Now, and in after years, Baltimoreans can appreciate what the head of the Police Department did for the protection of the lives and property during those days that tried men's souls. By day and night, the Marshal of Police was seemingly tireless. Walking and riding over the city, whom he had stationed at dangerous points, guarding with the faithfulness of a watch dog the great trust imposed upon him, losing sleep and rest without a murmur, Thomas F. Farnan stands out against the lurid light of the flames and smoke a truly heroic figure. Lest the reader should think that this tribute is overdrawn, the writer can truthfully say that he is acquainted with his subject from the closest and most personal kind of observation. For many days and many nights he was thrown constantly with the Marshal, watched his untiring efforts for the protection of the public, made the rounds with him over smoking and blistering ruins and day by day saw more threads of white silvering the head of the man who was throwing his whole body, thought, soul and action into accomplishing the great task which fate had thrown upon him. It was no uncommon thing in the four weeks following the fire for the Marshal to enter his private office, sit down at his desk and then fall asleep from utter physical exhaustion. It was at those times that his office force and those whom duty had gathered around him moved softly and talked in whispers, grateful that the Marshal was able to snatch even a "cat nap." In their hearts they would wish that the district call bells would not ring and that the telephones for the moment would be silent. It is a picture that comes before the writer with wonderful distinctness, the greying hair, the strong face, furrowed from thought and loss of rest, the exhausted pose, as with head resting on his hand, he leaned on the desk under the full glare of the electric light. Then would come the jangling call of a station house bell, or some subordinate officer would telephone in for directions. The call would hardly sound through the room than the Marshal would be on his feet to answer it personally, for in those days he exercised a personal direction of details that was truly amazing. The work accomplished by the Marshal during and after the fire extended a reputation that was becoming national, and when he attended the convention of the National Police Chiefs in the June following, the heads of every police force in the country, represented at that notable gathering, crowded around him and congratulated him on the manner in which he had protected his city and people during their great trial by fire. Thomas F. Farnan was born in Baltimore on March 15, 1846. After a few years in the public schools his parents sent him to Calvert Hall, but scholastic affairs were not much to his liking. He wanted to earn his own living, and finally, seeing that he was determined, his parents allowed him to get a position as errand boy in a music store. When he was 18 years old Thomas F. Farnan was apprenticed to a carpenter, and later he became a millwright.

On April 30, 1867, he received his commission as a policeman and was assigned to the Southern District. On February 1, 1870, he was promoted to the grade of sergeant, and a year later was made lieutenant of the Southern District. It was while serving in this position that the future Marshal began showing the police ability which has forced him steadily upward in his profession. On October 15, 1885, Lieutenant Farnan was promoted as captain of the Southern District, but he only remained in that district one day, and on October 16 was placed in command of the Central District, which was then, as it is now, the most important district in the city. When Deputy Marshal Lannan's post became vacant in 1893, Captain Farnan became Deputy Marshal under Marshal Jacob Frey. From that period until August 8, 1902, Deputy Marshal Farnan ably and efficiently acted as assistant to the Marshal, and at many times was acting Marshal of the city. A few days before Deputy Marshal Farnan received his appointment to the highest office in the Department the Commissioners had elected Police Magistrate J. McKenney White to the position. Justice White did not qualify nor receive his commission, as, convinced that he did not have the qualifications to make him a successful Marshal of Police, he informed the Commissioners by telegraph that he could not serve.

It was significant of the feeling of the entire Department that when the Marshal received his appointment and the members of the force wished to testify their appreciation of his final promotion that they sent him a huge floral ladder, the rungs of which were lettered. The first rung was inscribed "Patrolman," while the highest rung bore the inscription "Marshal of Police."

If Thomas F. Farnan has made a good chief of police, his record as a patrolman, sergeant, lieutenant and captain shows equally as well. One of his first cases was that of George Moore, alias Woods, a notorious thief and desperate character. Capt. Wallace Clayton, of the schooner Pringy, docked at Bowley’s Wharf, was assaulted and robbed one night and the thieves cut out one of his eyes. The assault and robbery aroused a great deal of indignation, and though the thieves left no clue behind, Patrolman Farnan worked assiduously on the case for nearly a year, struck a trail finally and arrested Woods. The suspect denied the crime, but Captain Clayton positively identified him as one of his assailants, and, with the evidence collected by the young officer who had been on his track, Moore, alias Woods, was convicted and sent to the Maryland Penitentiary for fifteen years. One night when the Marshal was a sergeant, he met a man who was deaf and dumb. The man, who was a giant in stature and muscle, had committed an assault. Sergeant Farnan placed him under arrest, but the subject suddenly wheeled about, caught the Sergeant's arm and threw him over his shoulder as though he was a sack of potatoes.

With both his hands held by the giant, the sergeant was at his mercy. Without apparent effort the man climbed up the stairs of a house in the neighborhood until he reached the attic, Sergeant Farnan found himself face to face with three other men whom he knew to be men of desperate character. Realizing his position, the sergeant told the three men that if they did not assist him in arresting the deaf and dumb subject, he would hound every one of them if he got away alive. The men knew Sergeant Farnan and felt they had better take sides with him. Throwing themselves on their former companion, they grappled with him while Sergeant Farnan tried to snap the nippers around his wrists. Struggling, the five men pitched down the steep stairway together. The struggle on the staircase was more than its crumbling, ramshackle supports could stand, and it gave way. The mass of humanity, of which the sergeant was a part, rolled out on the sidewalk, and the sergeant, as he struggled, managed to rap on the sidewalk with his espantoon. Other policemen responded, and it took eight of them to land the man in the Southern Station. Guilford alley, at that time one of the worst localities in South Baltimore, was a portion of Patrolman Farnan's post, and the first night he spent in that neighborhood he made sixteen arrests. There were no patrol wagons in those days, and the young officer was obliged to literally fight and drag his prisoners to the station. One of the most eventful periods of the Marshal's life was during the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad riots of 1877, when he was a lieutenant in the Southern District, under command of Captain Delanty. Lieutenant Farnan was placed on guard at Camden Station with a force of but three men. When the Fifth Regiment arrived at Camden Station the mob threw stones at the soldiers and Lieutenant Farnan saw one of the mob leaders hurl a large paving stone. At once he seized the man and put him under arrest, although his fellow officers begged him not to try and get his prisoner through the crowd. "I have arrested him and will take him to the station," said the lieutenant, and started with his prisoner. The mob made a rush for him. Women called from the windows overlooking the scene and begged the young officer to take refuge indoors and save himself from being wounded or killed. Shouted at and threatened by the mob, Lieutenant Farnan kept his head, but as the crowd pressed around him, he realized that he must impress them with his determination. Drawing his pistol, he pressed it against the head of his prisoner. "You men," he cried to the mob, "if this man is a friend of yours, you had better keep back." Then turning to his prisoner, he told him if he did not tell the mob that he was willing to go to the station he would blow his brains out. Thoroughly frightened, the man told the crowd he was perfectly willing to go with his captor. The crowd withdrew and Lieutenant Farnan was the only policeman who got through the mob with a prisoner. During the forty years he has been in the police service Marshal Farnan has received only one reprimand, and that came from an old Irish woman during the Cathedral Centenary. The Marshal had a large force of police on hand to see that the crowd was kept orderly and did not infringe upon the space set apart for the Church, State and municipal dignitaries. One little group stood in a place that was especially reserved, and the Marshal walked over to them and politely requested them to move forward. "Oh, go on, Tommy Farnan, and don't get smart with those who knew you when you was a boy. We've got as much right here as you have," exclaimed the old lady. "That's right," replied the Marshal, "but if you'll walk over here with me, I'll show you where you can see everything and not be in the way," and he conducted the little party of sightseers to a point of sightseeing vantage. "You always were a good boy, Tommy," said the old lady, and the Marshal smiled under his gray moustache as she continued, " I 'm sorry I spoke cross to you, and don't let it worry you, darlin." So, the Marshal smiled at his first reprimand and its quick withdrawal. Incidentally, and in connection with the Cathedral Centenary, it may be remarked that Cardinal Gibbons is a personal friend and admirer of Baltimore's Marshal of Police. Only a short time ago the distinguished Churchman said: "In these days, when the press is full of articles regarding the acceptance of bribes by public officials and the wrong conduct of those who have been commissioned to high offices of public trust, there has never been the slightest hint of stigma cast upon Thomas F. Farnan, the head of the Baltimore Police Department. He is a splendid and efficient official and his work and memory should in future days be remembered and honored by his fellow citizens." Marshal Farnan is a practical policeman and not a mere man of theory. He believes in a strict order of police discipline, but he has no fads and frills. He asks, demands, that his subordinates do their full duty, and if they are lax, negligent or disobedient, he quickly brings them to book. The policeman who makes a mistake or is guilty of an indiscretion, and admits it to his chief, finds a willing and kindly listener, a critical one, perhaps, but one who knows from long experience the difficulties, temptations and trials of those who wear the blue uniform and brass buttons. To such the Marshal is a kindly adviser. To Police Headquarters come many complaints against officers. Sometimes these complaints are well founded and at other times they emanate from political sources or from individuals who are incensed because subordinate members of the Department insist upon them obeying the laws. When complaints are received the Marshal makes a full investigation before reporting them to the Board of Commissioners. If the complaint is justified, the policeman is haled before the Board and asked to explain his conduct. If the Marshal finds that the complaints are not justified, or are laid because of politics or other interests, he is quick to discover their true meaning. Every man in the Department knows that its head will always support him as long as he does his duty and conducts himself as "an officer and a gentleman." The Marshal generally knows how to properly judge a policeman, for one learns many things in an experience of forty years on the police force of a large city. Forty years' experience as a policeman has made the Marshal very astute, a little doubtful of human nature, but has never hardened him. He is grim and stern enough with the professional criminal, but to the youth, or unfortunate, who has committed his first crime and has fallen into the hands of the police, he is always kindly, though absolutely rigid in carrying out the law. "Many criminals do wrong by choice," said the Marshal recently, "but there are some who are almost forced into a criminal life, because of their surroundings and other circumstances. I believe in treating all of them fairly and justly. The days when prisoners could be treated brutally by the officials who had them in charge have passed, and it is well they have, for it shows that the world is becoming really civilized and less brutal. I believe in police officers taking their prisoners 'in' at any cost. Once a policeman takes a man into custody, he should never let him go until he lands him in the station. If in doing this he is obliged to use his espantoon, or even his revolver, I believe he is justified, but he should never pull, haul or roughly handle a prisoner simply because he is an officer and wears the police badge of authority. In these days, I am glad to say, people recognize the law and its officers and there are but few cases of men resisting arrest and being clubbed for their resistance." In his domestic life the Marshal sets an example to the members of the force he directs and to Baltimoreans in general. His home—and it is a home in every sense of the word—is on Lombard street, near Fremont. Rid, if even for a short time, of the cares of office, he makes for his own fireside with the rapidity of a carrier pigeon seeking its loft, for awaiting him is the wife and mother who has been his domestic mainstay and companion for nearly 40 years. Then, in the soothing atmosphere that arises from his own hearthstone, the Marshal is no longer the grim chief of police, but the affectionate husband, the thoughtful head of the family, the father—yes, and grandfather, for the third generation of Farnan’s gather around him, climb on his shoulders and toy with the gilded badge that is an insignia of honor the Police Department or who is at all familiar with the force and its methods of operating and working. That he has been able to accomplish so much is due in a large measure to the fact that in all questions relating to the police or to the protection of the public from accidents and the attacks of criminals or evilly disposed persons the Deputy Marshal and Marshal Farnan, his chief, work in perfect unison. Not only are the Marshal and his Deputy close official associates, but they are very warm personal friends. Each appears to know instinctively the ideas of the other and to agree with them and this creates a harmony of action and effect that cannot but be of benefit to the whole Department and to the interests of life and property that it safeguards. Deputy Marshal Manning has inaugurated and put into effect several new ideas in connection with his work at Police Headquarters. He takes a great interest in statistics in matters that relate to the Police Department and the public. During the past year he has put into operation a system by which the records of all murders, suicides and accidents, fatal and otherwise, are tabulated and are monthly given to the public through the medium of the daily newspapers. The duties of Deputy Marshal Manning are manifold. In case of the sickness or absence from the city of the Marshal he exercises full command over the force. He must attend the Marshal's office and assist the Marshal by attending to such parts of his duties as the latter may designate. When his services are not required for the performance of such duties, he must inspect the members of the force on duty in the streets and he must daily visit as many of the station houses as practicable. He must repair in person to all serious or extensive fires in the City of Baltimore and to all riotous and tumultuous assemblages, and, if the Marshal is not present, take charge of the police and act as the Marshal. The Deputy Marshal has, under the direction of the Marshal, supervision over the police patrol boat, its officers and crews, and must see that proper care is taken of the vessel, its machinery and equipment. Connected with these specific duties there are thousands of details that are quickly grasped and disposed of by the second in command of the force.

The Deputy Marshal is comparatively a young man, and it required him just a little over 20 years to work his way to the highest position in the Police Department under the civil service, for the Marshal is appointed for a term of four years by the Police Board.

The Deputy's parents, Mr. Thomas and Mrs. Jeannette Manning, were Scotch-Irish. They lived in Seneca county, New York, where the Deputy first saw the light of day. He was born on October 1, 1855. When a youngster he attended the Catholic schools of the parishes in which he lived. When he was 12 years old his mother moved to Baltimore, and for two more years James Manning attended school here. Although he worked, he attended night school. Later he took a course at Eaton & Burnett's Business College. At the age of 15 he began to learn goldbeating, and his relatives thought he would continue to pound away in the little shop for the rest of his life. Despite the fact that the present Deputy Marshal looks and is the picture of health, he was not so fortunate in his younger days. He gave up goldbeating and went to work as a clerk for Messrs. Tyson & Bro., grain merchants. But this, too, disagreed with him and his health became so bad that Mr. Manning got up every morning and took long walks for exercise, lack of which caused his trouble. He put in his application for a place on the police force and said that if he had been subjected to such a rigid examination then as the men are now, he would probably have been rejected. One day in April 1882, he was notified of his appointment, and that night he reported at the Western Police Station for duty. Captain Lepson, then at the Western, took a liking to the young officer. After he had been on the force some time the Captain wanted him to become turnkey. He pointed out that the duties would not be hard, that his clothes would not cost so much, and that he would not be exposed to such rough weather. His friends told young Manning he was little short of crazy for not accepting the position, but Patrolman Manning wished to elevate himself, and he realized that he could only climb the ladder by getting good cases. It was not long before he displayed marked ability. Though he had made many arrests, the first very important case that came his way occurred in November 1887, when he arrested James Johnson, a burglar. Johnson was regarded as a dangerous man, because he was always heavily armed, and his peculiar specialty was robbing houses while the occupants were asleep. He expected to be shot at if caught in the act, so he went prepared to give battle. One morning two houses on Saratoga street were robbed, and a long Newmarket overcoat was among the things stolen. A few hours after the report was made at the police station Patrolman Manning went to a pawnshop to warn the broker about the stolen articles. As he was entering the place, he saw Johnson pawning an overcoat. While he did not know the man, he felt that the coat was the one for which he was looking. Johnson, in the meantime, had gotten out the door, but he was overtaken. When searched at the station house sufficient evidence was found in the suspect's pockets to connect him with eleven cases of burglary. He was sent to the Maryland Penitentiary for nine years. On February 6 of the following year Manning arrested Frank Sullivan and Ned Spurrier, charged with assaulting and robbing Mr. Jacob Eakle, of Hagerstown. Patrolman Manning was on day duty at the time and was notified one afternoon that an old man from the country had been beaten and robbed on his post in broad daylight. Being young and energetic, the patrolman felt that he must get the case, or his superiors would think the grass was growing under his feet. He hurried to Pratt and Penn streets, where the holdup took place, and saw the old man, with blood streaming down his face from the blows of his assailants. Then he felt a slight tug at his coat sleeve. He turned and saw a small boy, who led him aside. The youngster said he had seen the robbery and had just passed the highwaymen on Fremont street. With his diminutive assistant, Manning ran to Fremont street, where the youngster pointed out two men. Realizing that the men would run if they had the opportunity, Patrolman Manning ran as lightly as possible and burst between the men. Before they had recovered from the shock of the collision a strong hand clutched both of their collars. At the patrol box Sullivan became unruly.

He twisted Patrolman Manning's thumb back until he dislocated it, but the officer did not release his hold. Though the agony was intense, he did not say a word in complaint, as no one in the crowd would at first aid him. When it seemed that Sullivan would surely get away the prisoner became crazed. He kicked at the crowd and acted so that he came near being mobbed. When the men were searched at the police station Mr. Eakle's watch was taken from Sullivan. Then the young patrolman was given the position of telephone man in the police station, and this valuable experience has stood him in great stead. On March 31, 1888, he was promoted to sergeant, and on August 21, 1891, he was again promoted. It was while a round sergeant that the Deputy waged a war on gambling houses and violators of the liquor law. One of the best raids he ever made was upon a gambling joint in the Western District which had a cigar store front. The store was closed about 9 o'clock every night, and the players used the second floor. Two complaints had been made about the place, both persons declaring they had been fleeced. Early one morning, when all the players had left the building, Round Sergeant Manning and the present Lieutenant Poulton talked the matter over. Manning said he wanted to get into the house to "get the lay of the land," so he climbed the back fence and, with the aid of a ladder, crawled through a second-story window. He made his investigations and looked for the best point to attack, and found it in the kitchen, which, he discovered, was not used. Everything in the room was covered with dust, and the windows and shutters were bolted. The bolts were slid, and the shutters unlatched. Two or three nights later the cigar store was closed, but the lights in the second story were so bright that the "Rounder" knew there was a big game on. He got his squad of raiders and climbed the back fence. Having removed their shoes, the policemen crept into the kitchen, after one of the men had climbed through the kitchen window.

Round Sergeant Manning knew where the game was, so he started to crawl toward it in the darkness. Suddenly he became aware that a sentry stood on the landing above him. "We've got to run for it," he shouted to Poulton, and they reached the sentry's side and clutched him by the throat before he could say a word. The man was too surprised to yell. When they saw the officers in uniform the players were dumfounded. As a round sergeant the Deputy was well informed regarding the Chinese in Chinatown, and he made several raids. One was on Bow Sing's place, in Marion street. Numerous complaints had been made against the dive, and the Deputy started out one night to raid it. He knew the house was barred and provided with signals to warn the gamblers. He knew also that no one could gain entrance until he had shown his face to the doorkeeper, who looked through a glass panel.

Finally, he decided upon a plan. He took his men into the rear yard of a house occupied by several bad characters, which was next door to the dive. All the occupants were kept under surveillance to keep them from warning Bow Sing and his guests. Then, with the door of the house opened just far enough for him to see what was going on, the Deputy waited. Soon a young Chinaman came along, and, thinking no one was in sight, gave the mystic sign and the door was opened. Before the Chinaman could step across the threshold the Deputy had knocked him sprawling and dashed into the den. The gamblers were fined and the Chinaman who was knocked down was ostracized by his fellow-countrymen. In another Chinese raid Round Sergeant Manning dashed into the "joint" and took it by storm. He was in citizen's clothes, and the Chinamen could not stop him until he was alongside of the gaming table, about which 50 Chinamen were seated. The other members of the raiding party were locked out, and the Deputy was left in the den with the gamblers, but no one made an attempt to injure him.

The only time the Deputy's life was in actual danger was when he arrested Lewis Stewart, a young man who lived in South Baltimore some years ago. Stewart and a girl friend had been at a ball and quarreled on the street. Patrolman Nicholson ordered them to move on, and Stewart turned on the officer and shot at him. Round Sergeant Manning was coming down the street, and Stewart approached him with the pistol in his hand. In a minute the young man found himself on his back, but as Manning looked down at his prisoner, he found the muzzle of the pistol staring him in the face. With a quick movement of his hand the round sergeant pushed the young man's hand away just as the weapon was fired. His good work as round sergeant earned promotion, and he was sent to the Central District, where his opportunities were greater. Later he was sent to the Northwestern District, and on April 6, 1898, he was promoted to lieutenant. His good working the house won a captaincy for him August 6, 1900, and he was assigned to the Northeastern District. When he took command, the district needed a strict disciplinarian, and he was the right man for the place. Soon his men began to see him in the district at midnight and at all hours. They met him here, there and everywhere. As a result, everybody worked hard. The most daring piece of work Manning did as captain was to arrange with ex-City Councilman John Stone to be held up on Sinclair Lane, a dark walk in the northeastern suburbs. It was learned that Herbert Carter, alias John Smith, and Llewellen Winslow, alias Louis Keene, had planned to rob Mr. Stone. Mr. Stone was in the coal business, and his receipts Saturday night were said to be large. These he carried home with him and the two young men, it was said, intended to rob him. Captain Manning sent for Mr. Stone and told him of the plan. He got Mr. Stone to consent to be held up. When the hold-up took place Detective Dougherty, Round Sergeant Arbin, Round Sergeant Leverton and several other policemen were nearby. The hold-up was not successful because the officers fired at the men too soon. In the chase which followed one man got away but was caught later. Each man was given nine years in the Maryland Penitentiary. When Marshal Farnan was appointed, Captain Manning took the examination for the Deputy Marshalship. He passed with a high percentage and was promoted. Since that time, he has been out of the limelight, except when Marshal Farnan goes away, when he takes up the reins and handles the affairs of the Department.

![]()

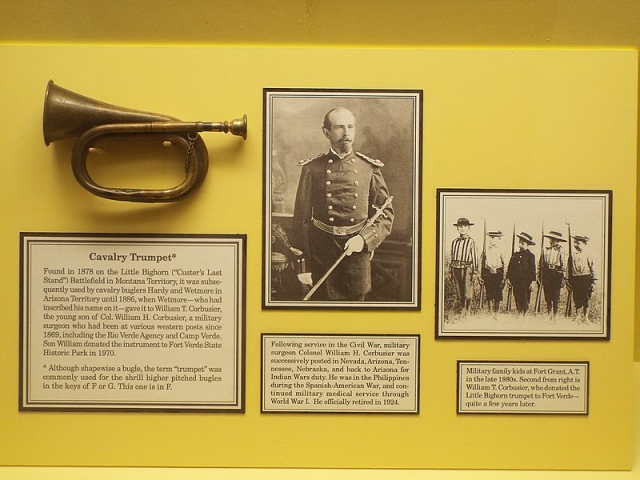

Custer's Last Stand Calvary Trumpet-1878

Click HERE to see full size pic

Click HERE to hear Audio File

![]()

POLICE INFORMATION

Copies of: Your Baltimore Police Department Class Photo, Pictures of our Officers, Vehicles, Equipment, Newspaper Articles relating to our department and or officers, Old Departmental Newsletters, Lookouts, Wanted Posters, and or Brochures. Information on Deceased Officers and anything that may help Preserve the History and Proud Traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to Honor the fine men and women who have served with Honor and Distinction at the Baltimore Police Department.

Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll