Sir Edward R. Henry

Baltimore Becomes The First American City To Adopt the Finger-Print System

26 November 1904

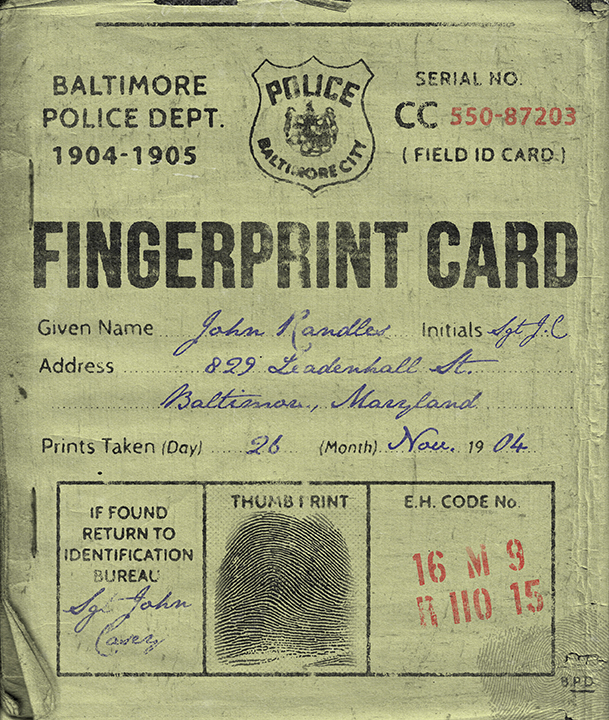

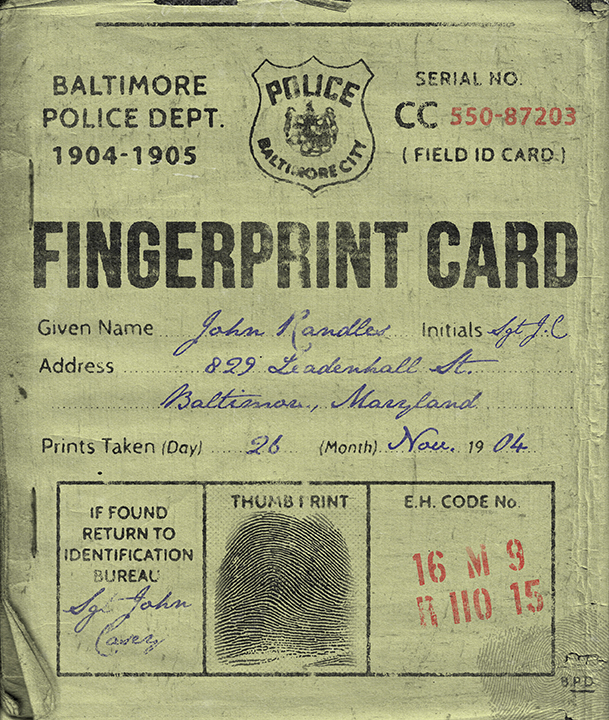

While researching Marshal Farnan of the Baltimore Police Department we came across a 1907 newspaper report that would indicate Baltimore's Police Department was the first in the United States to use fingerprinting to catalog criminals in our country officially. The 1907 article went on to report the following; "In line with this tendency in the ancient trade is the fingerprint method of identification, invented by E. R. Henry, of Scotland Yard, London. Shortly after its introduction, it was tried and put to use Baltimore. On 26 November 1904, when Sgt. Casey, chief of the local Bureau of Identification officially printed John Randles, a suspect being held on a theft charge. Randles had a criminal record and became the first person in the United States that was officially printed under this new system. Before this, they used the Bertillon system. The initial thought was to use both systems side by side, but time, cost and accuracy had us dropping the Bertillion System, which was also cut by other agencies around the country and the world for that matter when before long the only country using both systems was France, Alphonse Bertillon's home country was from.

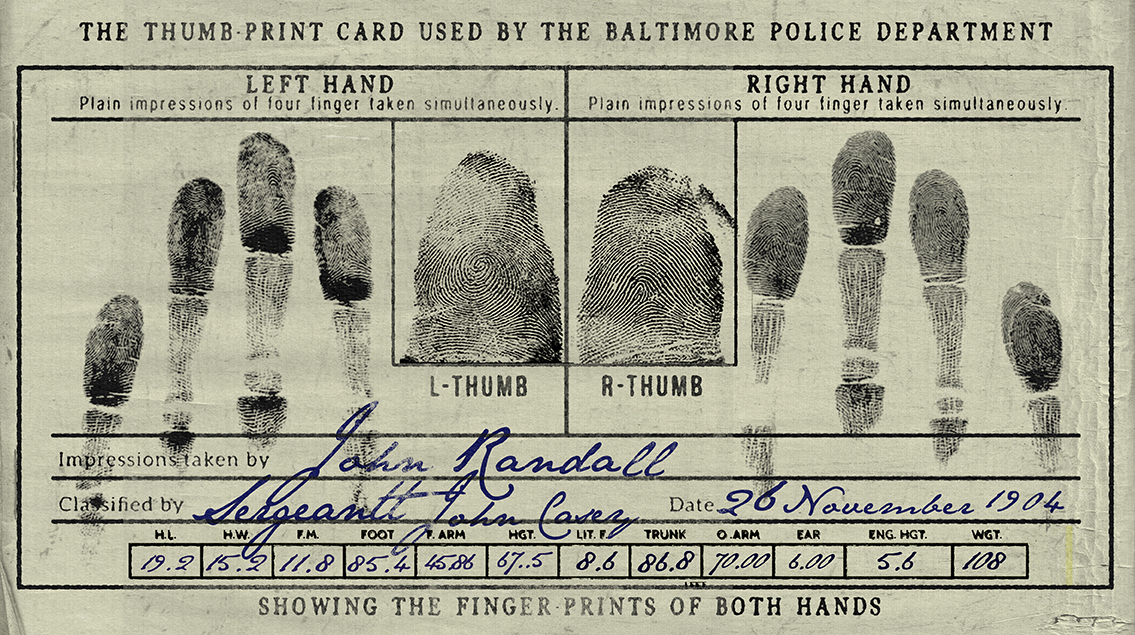

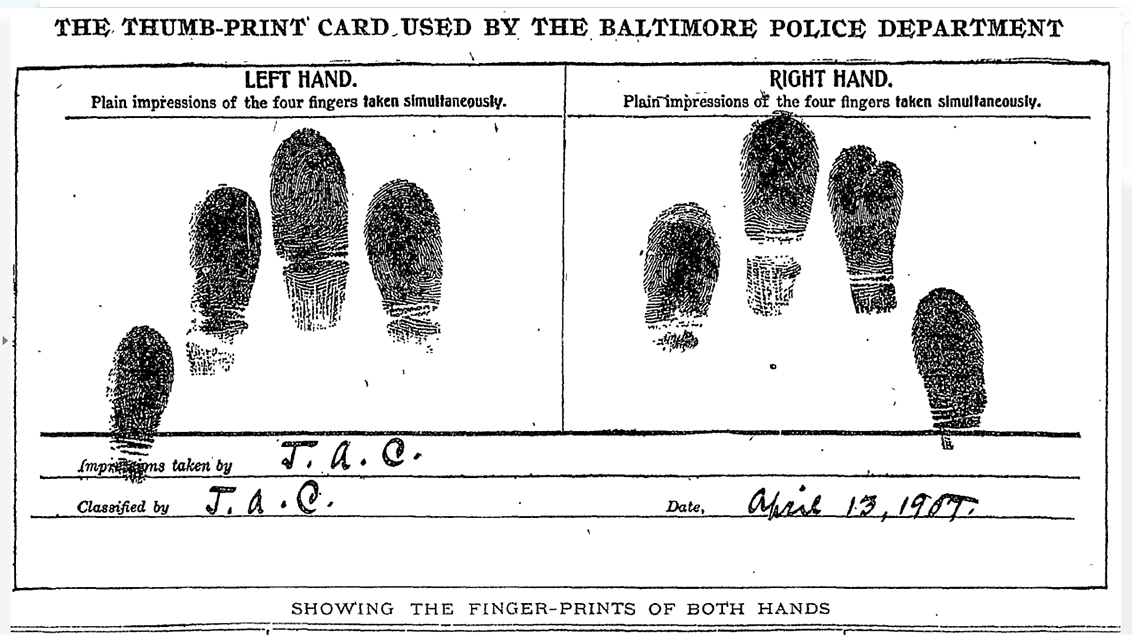

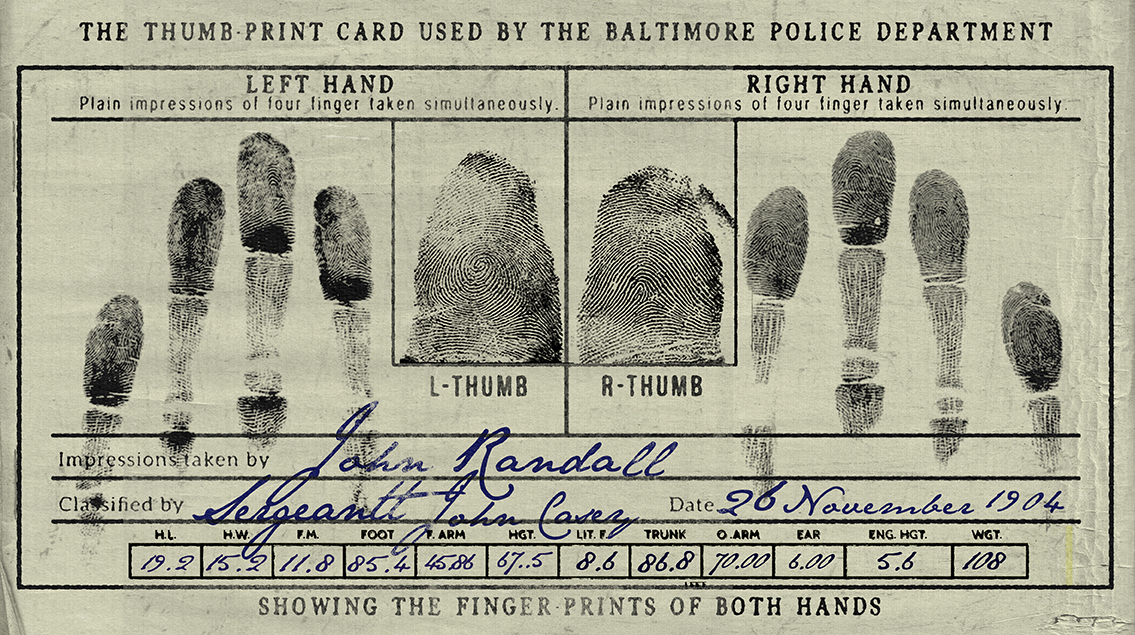

Authentic BPD Print Card Circa 1907

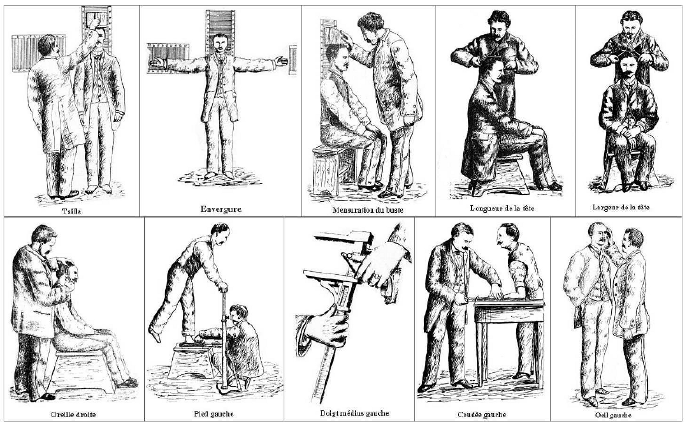

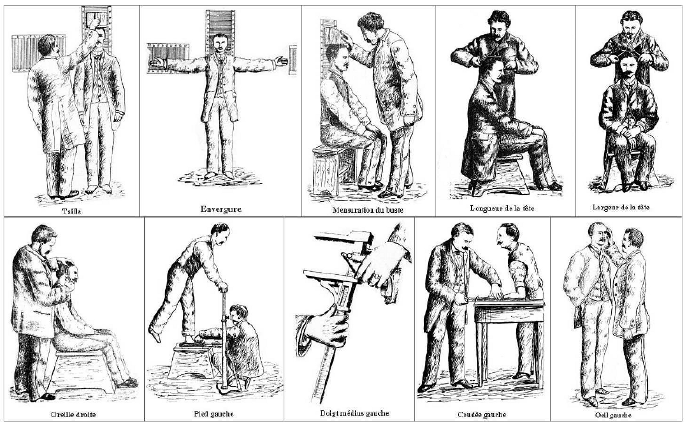

This version helps show the four fingerprint w/both thumbs and the Bertillon System. Showing why the fingerprints would be easier, and faster than said Bertillon System. 12 measurements, each with a photo, vs. four prints. The four fingers of each hand are two prints, and each thumb makes three and four, add to this two photos, a headshot, and a profile shot. Eventually, we would go to each finger individually, the four-digit groups, two palms for a total of 14 prints and two photos. All done rather quickly maybe 2 minutes per hand and a few seconds, for the pictures, roughly 4 to 5 minutes total per individual, over the Battalion System which took as much as many as three to four times that of the fingerprint system.

Click HERE or above article for full size story

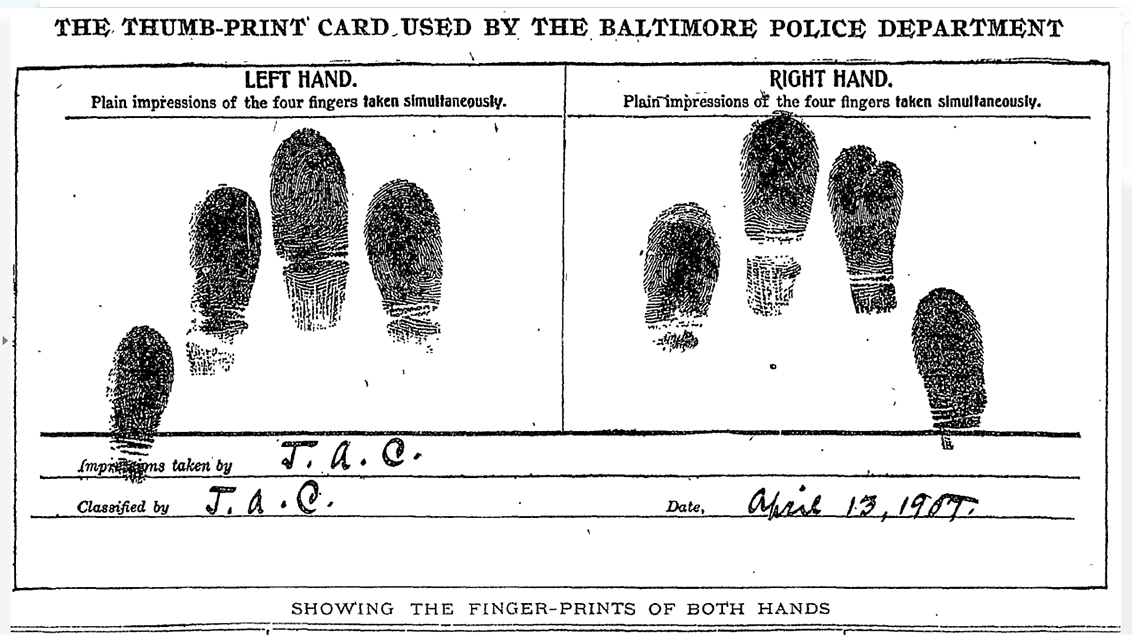

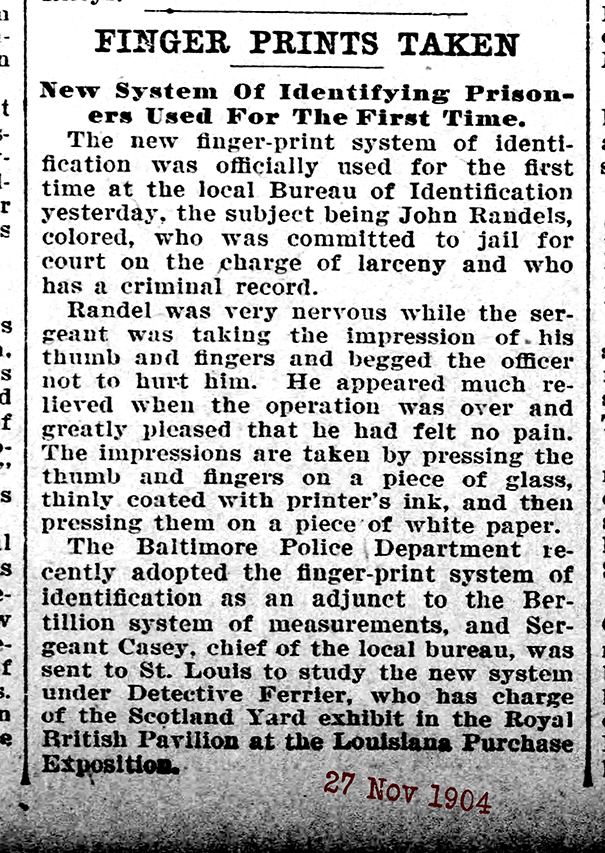

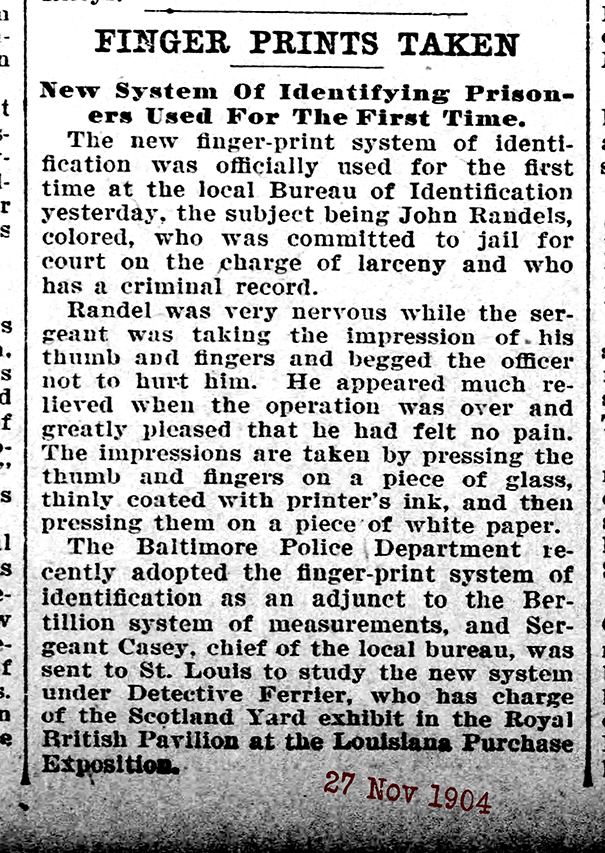

FINGERPRINTS TAKEN

The Sun (1837-1989); Nov 27, 1904; pg. 16

FINGERPRINTS TAKEN

A new system of identifying prisoners used for the first time

The new fingerprint system of identification was officially used for the first time at the local Bureau of Identification yesterday, (Saturday, 26 November 1904) the subject being John Randles, colored, who was committed to jail for court on the charge of larceny and has a criminal record.

Randall was very nervous while the Sgt. Casey was taking the impression of his thumb and fingers and begged the officer not to hurt him. He appeared much relieved when the operation was over, and greatly pleased that he had felt no pain. The impressions are taken by pressing the thumb and fingers on a piece of glass, thinly coded with printer’s ink, and then pressing them on a piece of white paper.

The Baltimore Police Department recently adopted the fingerprint system of identification as an adjunct to the Bertillon system of measurements. Sgt. Casey, chief of the local Bureau, was sent to St. Louis to study the new system under Detective Ferrier, who had charge of the Scotland Yard exhibit in the Royal British Pavilion at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition.

Random Mug Shot

3 Jan 1905 in an article entitled: 187 Photographed and Measured - The article gave an inauguration date of 7 Dec 1904, for the start of the fingerprint system in the following article:

HIS BRAVERY RECOGNIZED

The Sun (1837-1989); Jan 3, 1905; pg. 12 187 Photographed and Measured

The annual report of Sergeant John A Casey, Chief of the local Bureau of Identification, and his assistant, Sergeant Higgins, shows that during the year that just ended 187 prisoners have been photographed and measured according to the Bertillon system. The fingerprint system of identification was inaugurated (Wednesday) 7 December last (1904) and since then 25 imprints have been taken. The scenes of six murders were photographed, as were also four unidentified dead men. Photographs and records to the number of 338 were sent to other police departments, and 217 photographs and records were received.

Bertillion System

BERTILLON IS MODEST

The Sun (1837-1989); Nov 8, 1905; pg. 7

Giving Credit to the English for some of his work.

HIS FINGERFRINT SYSTEM

Thinks all the criminals in the World will ultimately be identified.

“I learned the foundation of my fingerprint knowledge from the English.”

This striking and at the same time characteristically modest utterance was made during an interview with Mr. Alphonse Bertillon, the Great French anthropometrical and expert, the man whose name has associated the world over with the identification of criminals by measurements and fingerprints.

Mr. Bertillon was fresh from the witness box at Bow Street, where he had been giving some of his deadly fingerprint evidence with regards to the recent ghastly crop of Paris murders.

In appearance, M. Bertillon is the clear thinker rather than the man of action, the scientist of the cloister rather than the public figure of the forum. To talk with him is to see that he has thought out the fingerprint system bit by bit, arched by arts, loop by loop, and whorl by whorl, even as he is sought out the science of anthropometry millimeter by millimeter.

A high four head, a well-balanced brow, a thin, oval face, a pair of serene dark eyes, a black mustache, obviously French, but not to pronounce in curl; trim, black beard, a complexion strongly reminiscent of parchment. Long and delicate fingers, a tallest and latest frame, and the ribbon of the Legion of honor almost imperceptible on the lapel of his coat; such in brief is M. Alfonse Bertillon, the terror of criminals.

“Do you think, M. Bertillon,” I asked him, “that the science of measurements whatever supplant the science of fingerprints?”

“No,” he answered very quietly. “I think the human measurement system will supplement and assist the fingerprint system in the ultimate marking down and tabulating of practically every known or potential criminal in the civilized world. The sister science will go hand in hand. The science that is based upon the fact that every individual has among his bones particular characteristic shapes and dimensions will march forward in unison with the science each arises from the circumstance that the fingerprints of practically everybody are different from the fingerprints of everybody else. Both these truths and the application of them in everyday criminal search and detection have been of enormous service to us in France, and it helped to read respectable society of many of the human harpies who prey upon it.”

“And what led you to take up the study and practice of fingerprint science?”

“Reading of the work of Herschel and Galton. I looked into what they were doing as pioneers of the fingerprint system. I became genuinely interested. I soon found that they were right, and I started collecting fingerprints of friends and of criminals myself.

“My subsequent experience in actual criminal practice has shown me that if do the fingerprints tally exact, it is practically certain that they are the prints of one and the same person. However, many of the population of the entire world may have passed that way and have handled the article on which the print has been made.”

“And the sister science to fingerprints. Your gift to the world, the science of the measurement of man, how did you first come to think that out?”

“Well,” answered M. Bertillon, with the ghost of a smile and a tiny depreciating’s rug of the shoulder, “I saw the need for some such system for the identification of criminals. I saw that the evidence of the photograph and the official description might very easily be made useless, and indeed has in many, many cases been quite nullified by the criminals little tricks of disguise. All the previous photographed and officially described criminals had to do was to alter the style of doing his hair and the color of it. To distort his features and one of the well-known ways, to remove or add a mustache, a beard, to alter the eyebrows or what not, and he had passed beyond the likelihood of recognition.

“But a man cannot change his bones. He cannot disguise the exact length of his nose, of his four head, the length and width of his head, and length of the left middle finger, the length of his left foot. “Experience soon taught me that these bony portions of the human frame rarely undergo any material change in the adult and that practically no two persons in the civilized world have the same combination of measurements. This great central fact, together with the marvelous faithfulness of the fingerprint record, has been of immense assistance to us in France in the detection of criminals, and the more of these records we take, the more strongly is the efficiency of the two systems of fingerprinting and measurements substantiated and proven.”

Sir William Herschel, cited above by M. Bertillon as one of his teachers, took many fingerprint observations while in India and was so convinced of the efficiency of the principal that he brought it back to England a mass of evidence on the subject. This was of great value to Mr. Bertillon.

Mr. Francis Galton, the other English fingerprint pioneer, after long and close study of the vast number of fingerprints, estimated that the chance of two sets of fingerprints being identical is less than one in 64 billion.

This is the march of science going triumphantly on, to the harassing and hindering of the human pest in his malignant deeds against society and social peace and safety. By a gracious feature of the internationality of brains grants, by M. Bertillon, has learned from us, and we, by Scotland Yard, have acquired from France.

To the comfort of peace-loving citizens and to the terror of evildoers, be it known that there has long existed between Paris and Scotland Yard a real, deep-seated entente cordial.

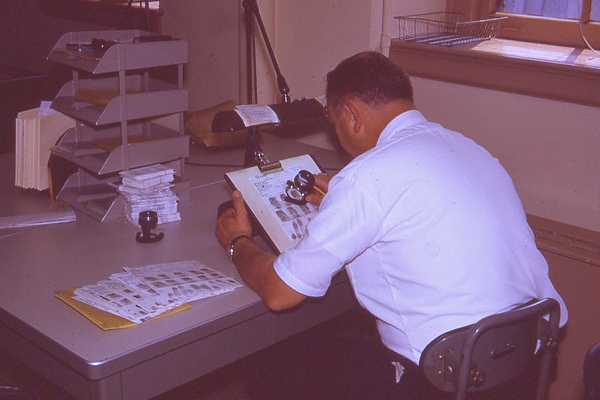

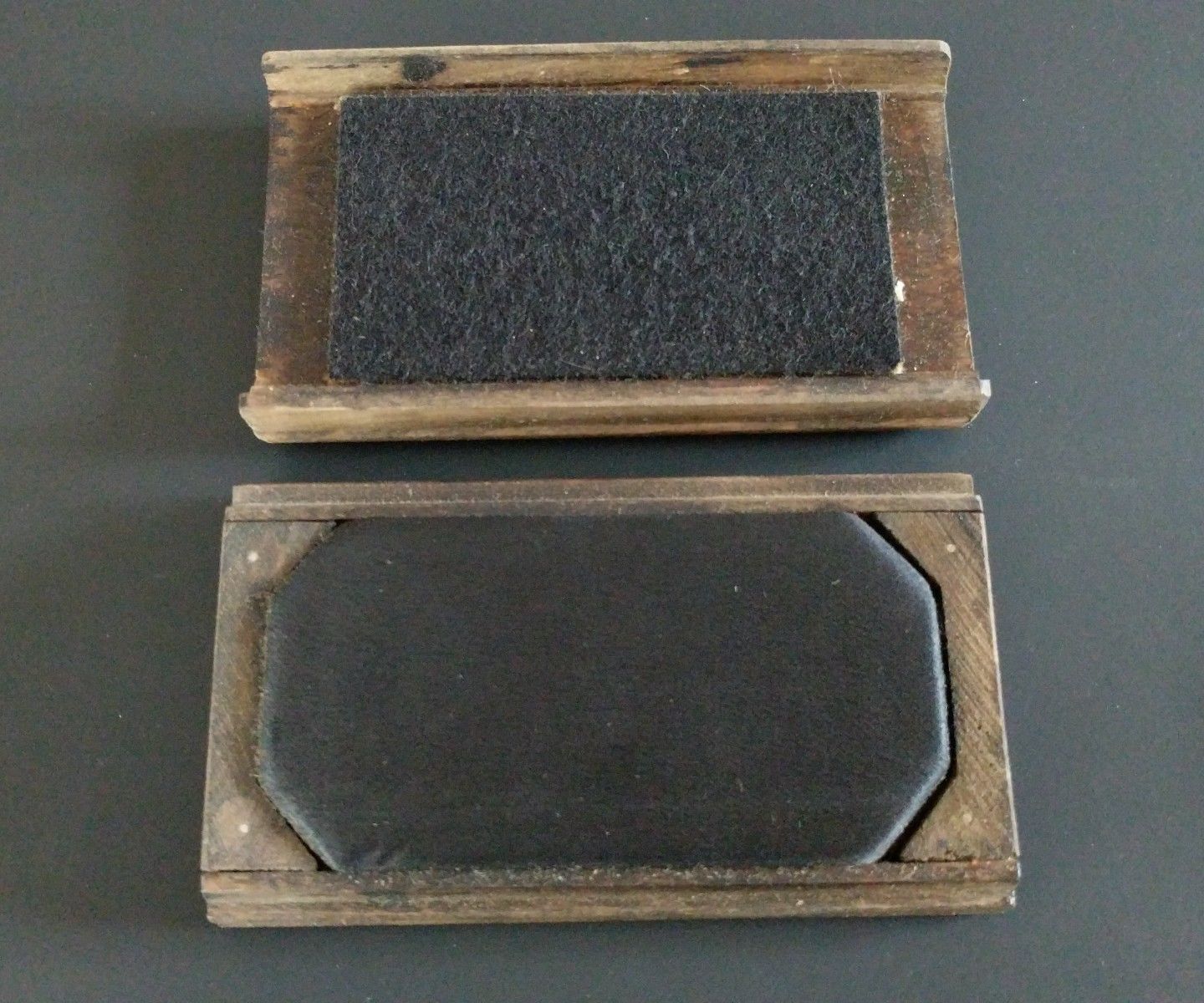

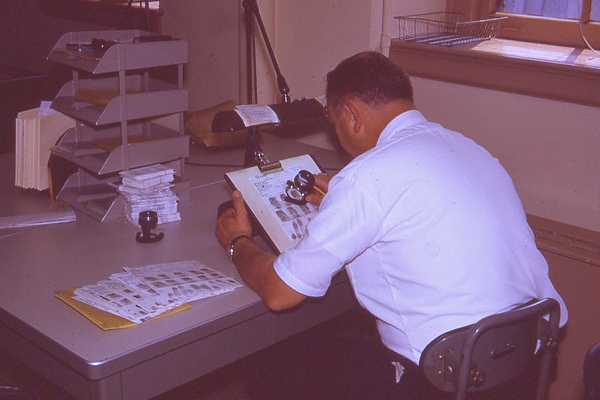

Portable Fingerprint station from a substation, most likely Eastern District Circa 1940's/1950's

In the drawer, we see ACE fingerprint Ink, a cardholder, roller etc.

The back part of the desk folds forward to reveal a panel of glass for rolling ink on and inking the subject's fingerprints.

On top of this is also a stand to hold the cardholder making it easier to roll the subject's prints onto the print card.

Here we can see the ACE fingerprint Ink, a glass panel for rolling the ink and inking the fingers, the stand for the cardholder

and other tools necessary to take a suspect's fingerprints and for storing the equipment needed to do so.

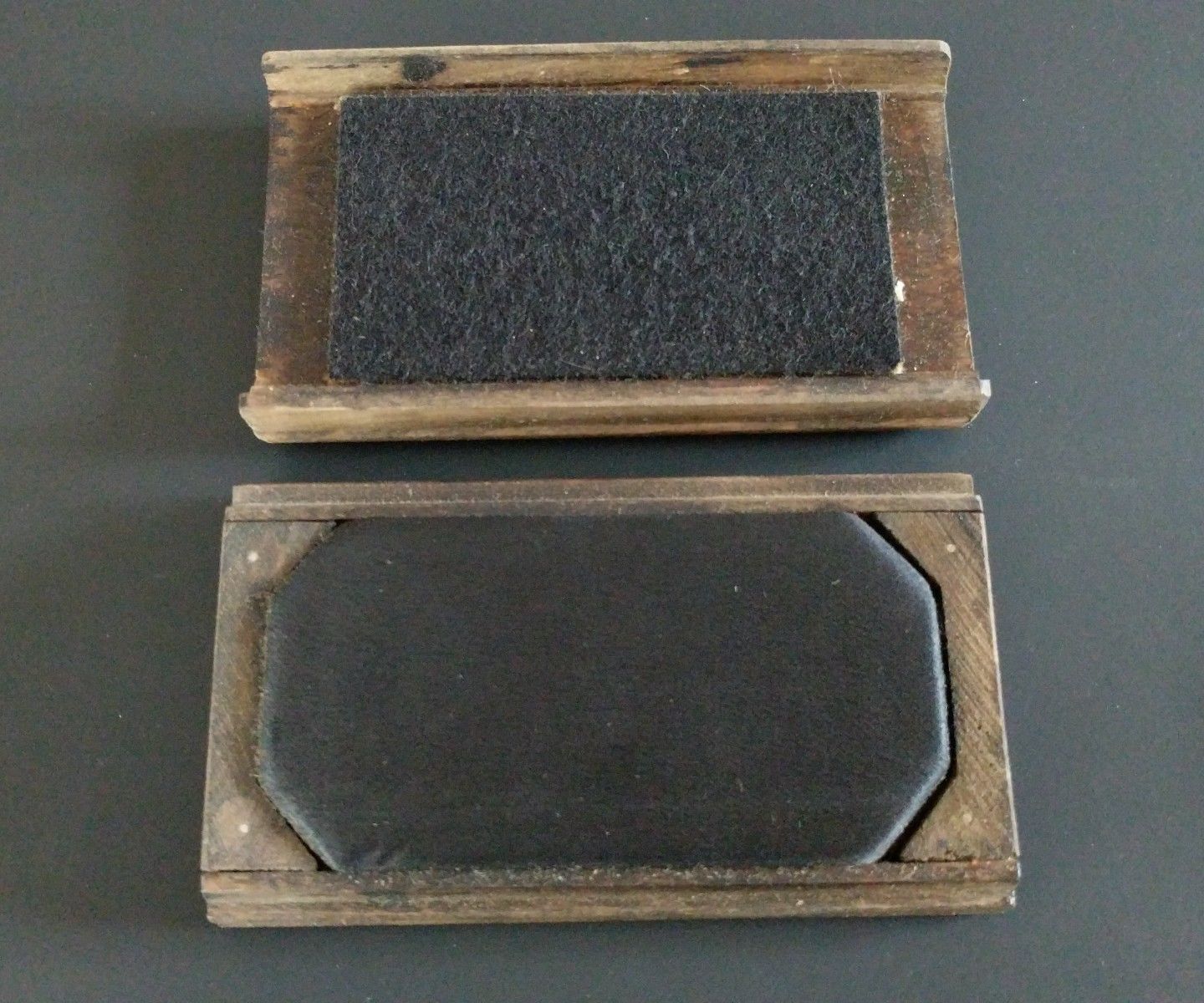

Here we have a wooden ACE fingerprint Ink-pad

The inside of the above wooden Ink-pad

FINGERPRINTS OF CROOKS ARE NOW AIDS OF POLICE

Apr 21, 1907

FINGERPRINTS OF CROOKS ARE NOW AIDS OF POLICE

Baltimore, The First American City To Adopt

NEW IDENTIFICATION METHOD

Thief-catching is becoming more and more a matter of system. With every other profession, it shares the tendency to a method that characterizes the present century.

In the old days, it used to be a free Chase in the open with no odds given, and a scrimmage at the end between the defenders of the law and its violators. But all this is passed. Criminals are now cataloged. When they are wanted the apprehension is gone about in a matter of fact, systematic manner. There is nothing left to chance.

In line with this tendency in the ancient trade is the fingerprint method of identification, invented by Sir E. R. Henry, of Scotland Yard, London, and later tried in Baltimore for the first time in the United States. By its means, a criminal is tagged and recorded without the possibility of error. His identity, once his fingerprints have been taken, can never be disputed, and his life story, with a summary of his habits and personal characteristics, is always where it can be reached at a minutes notice.

KEEPING TRACK OF CROOKS

For the last half-century, the constant effort in police circles has been to find some means by which a criminal's identity could be permanently fixed. The great utility of the rogue’s gallery and the system of keeping a record of all persons convicted in the upper courts has made this an evidently desirable one. But a rogue’s gallery or cabinet of biographies is of little use, it can be seen, is the identity of the lawbreakers is a matter of uncertainty. An alley S or the skies are easily assumed, so if there is no other way of fixing the identity of the person them by name or photograph the rogue’s gallery and criminal record might as well go to the trash pile.

To accomplish the desirable, and of absolute identification, various schemes have been proposed and tried. All have been based on the principles that there are certain parts of the human body whose form cannot be changed without detection.

First came photography, which was thought to have marvelous value. At one time, for instance, it was believed that a photograph was a sure means of telling whether or not a person was going to develop an eruptive sickness, for it was said that the irruption would show on the photograph even if it had not yet made its appearance on the sitter's face. Despite its many real virtues, however, photography did not adequately cover the ground desired.

FAILURE OF PHOTOGRAPHY

It had been supposed that a series of photographs showing a criminal in various poses – full face, half face, profile and so one – would be a complete means of identification should that criminal be apprehended at any time after the photographs had been made. This idea was proved a fallacy, mainly through the cleverness of the offenders, who found that a contortion of the muscles of the features materially altered the value of the portrait.

Anyhow, the scheme was wholly inadequate for the task it was at first supposed to perform. So many criminals looked a-like that in some notable cases their portraits were hardly distinguishable.

Photographs proved of such accessory value as a means of apprehension of criminals, however, that the gallery and camera were made a permanent adjunct to most police bureaus. Still, something other than pictures was needed for an absolute means of identification.

The Bertillon method was the next thing of consequence to make its appearance. Much has been written about the Bertillon method, and by many criminals and criminal – takers it is regarded as a sort of superstitious veneration, its intricacies seeming a sacred rite. It has proved very useful, but is not altogether infallible, as the case that happened in London about ten years ago suffices to show.

At that time to criminals were measured and it was found that their records were the same. This is rather a marvelous coincidence and is the only one recorded in the whole history of the system. Nevertheless, it shows that it is not entirely infallible. Other points to be urged against the Bertillon method are that it is complicated, time-consuming, and can only be applied to adult prisoners.

CLICK HERE FOR AUDIO

THE FINGERPRINT SYSTEM

Votaries claim for the latest arrival, the fingerprint system, that it was known of the faults of the Bertillon method and that it has all of its virtues. This is rather a broad assertion, but to prove it they point out that the fingerprint method is simple, quick, absolutely accurate and applicable to an individual of any age. They are intensely enthusiastic, but the process is rather new, and votaries of any new faith are always apt to go to the extremes.

If the E. R. Henry fingerprint system of identification pans out in practical working and it's testing in Baltimore seemed to show that it will, Palmists will be jubilant and materially minded of the world reproved, for the principle upon which it rests is one that fortunetellers have long banked upon.

It is the theory that the lines of the fingers of every person in the universe form patterns, which have no exact duplicate, and that moreover, these lines remain unchanged in an individual’s hand from his birth to his death.

It is a rather remarkable reflection. Look at your finger, and consider that there is nothing else like them in the whole universe and that probably there never will be. It reminds one of the stories of the little boy who after having been told of the wonders of nature looked up at his teacher with a puzzled face and asked if the Lord didn’t ever run out of ideas. It seemed too big to be true. Still, that is the principle upon which the Henry fingerprint system is based.

Designed using Ian Barnard's Software

There was never a form like this, and this was created solely to help tell the story.

The year was 1904, the day 26 November, The Sgt taking the fingerprints was Sgt. John Casey,

The suspect being Printed was Mr, John Randals he was held over of a Theft Charge

TAKING THE PRINTS If the skin of the hand is destroyed and grows back again in a natural manner, it's lined, after it has completed its growth, will be identical with those of the skin that was destroyed. It seems as if fate had stamped a trademark upon the hand of every individual. At all events, the only thing that will permanently destroy the telltale lines is a scar.

If you have ever gone to a palmist and had him (or her, as the case is more apt to be) smear your hand with black ink and press it on a piece of white paper, you will understand that once just how the fingerprint system is worked. If the palmists as afterward examined this impression with a magnifying glass and discovered interesting things in it, you will also know how the print is classified and filed in the Henry system of criminal identification.

The making of fingerprints consists of a clever use of glass and printers bank and a bit of care. The ink is usually black, or if not that, of some intense color, and is the same as that used for printing fine cuts or engravings. The glass is a strip about 5 x 6”. Upon the glass, the ink is spread in a thin coating.

Then a paper form with spaces reserved for the impression of the different fingers is laid upon the table beside the ink, and the glass and all is in readiness to take the prints of the fingers of the person whose record is desired.

PRISONERS ARE FRIGHTENED

These preparations are all very simple. They certainly don’t seem to have anything in them to frighten a person. But inmates in the Baltimore Bureau who are to be fingerprinted seem always to regard them in a Respectfully timid way. They think that there is some sort of a “hoodoo” about them. With the colored gentry, this is especially true. The idea of making a fingerprint evidently seems possessed of menace to them.

12 prints are made from each individual to be recorded. First, each of the ten fingers is printed separately; then the forefingers of each and together. A simple role of the ink on the glass and pressure upon the paper constitutes the whole mechanical part of the operation.

The next step in the making of the fingerprint record is a classification and filing.

The first term may not be understood, but the second seems simple enough. “Filing;” the word instantly brings to mind a picture of cabinets with their content arranged alphabetically.

Filing a fingerprint with us seem to be very easy of comprehension. In reality, it is the most difficult part of the process. Finger – Prince cannot be filed according to the alphabet. They must be put away according to fixed characteristics of their own, and this is why they must be classified before they can be filed.

Suppose a man is in custody. It is thought that he has a fingerprint record and that this record is desired by police officials. Would it be possible to look for it under the name the man gives? Certainly not, because this is, just as well as not, and alley us.

That is the whole point. If names were fixed quality in life and could not be changed, they would serve as a means of identification. Otherwise, identity must be ascertained using an individual’s personal characteristics. In this case, a fingerprint record must be found using a fingerprint and not by name.

SORTING THE PRINTS

The task of devising a means by which fingerprints could be filed was one of the greatest difficulty. By successfully carrying it through Mr. Henry gave his name to the process now standing as a monument to him. The peculiar virtues of fingerprints as a means of identification were known before his time, but there was no way to classify them.

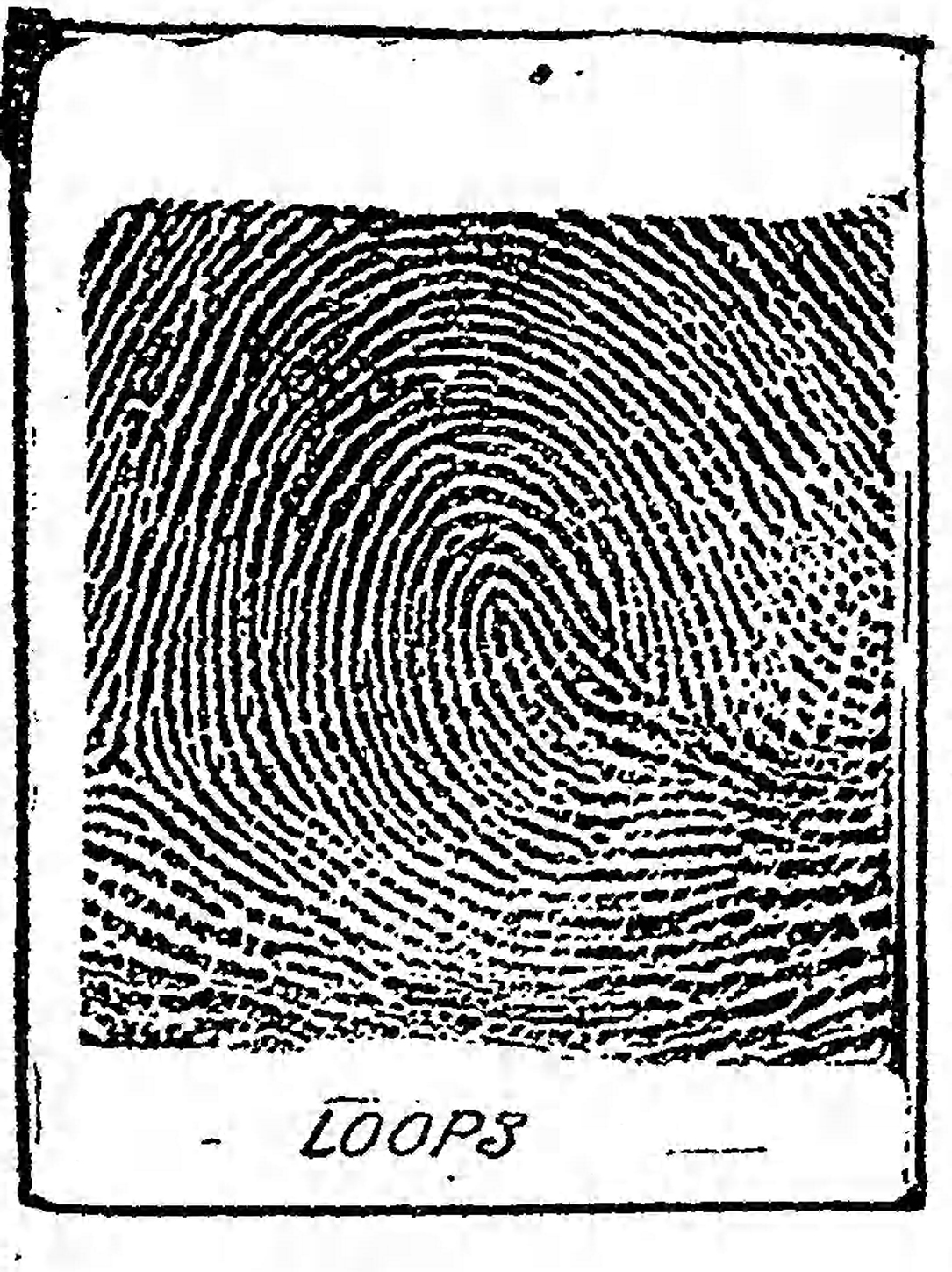

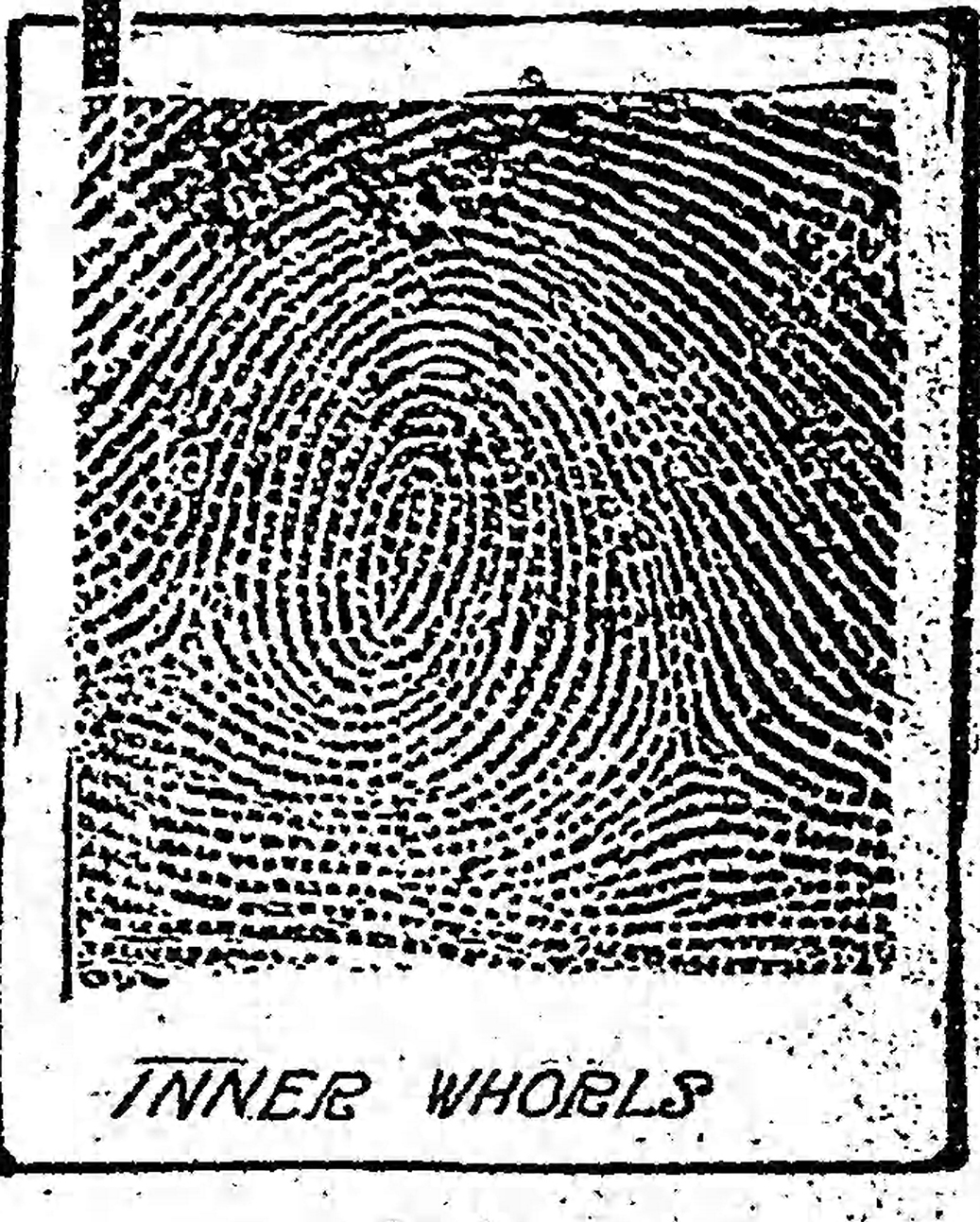

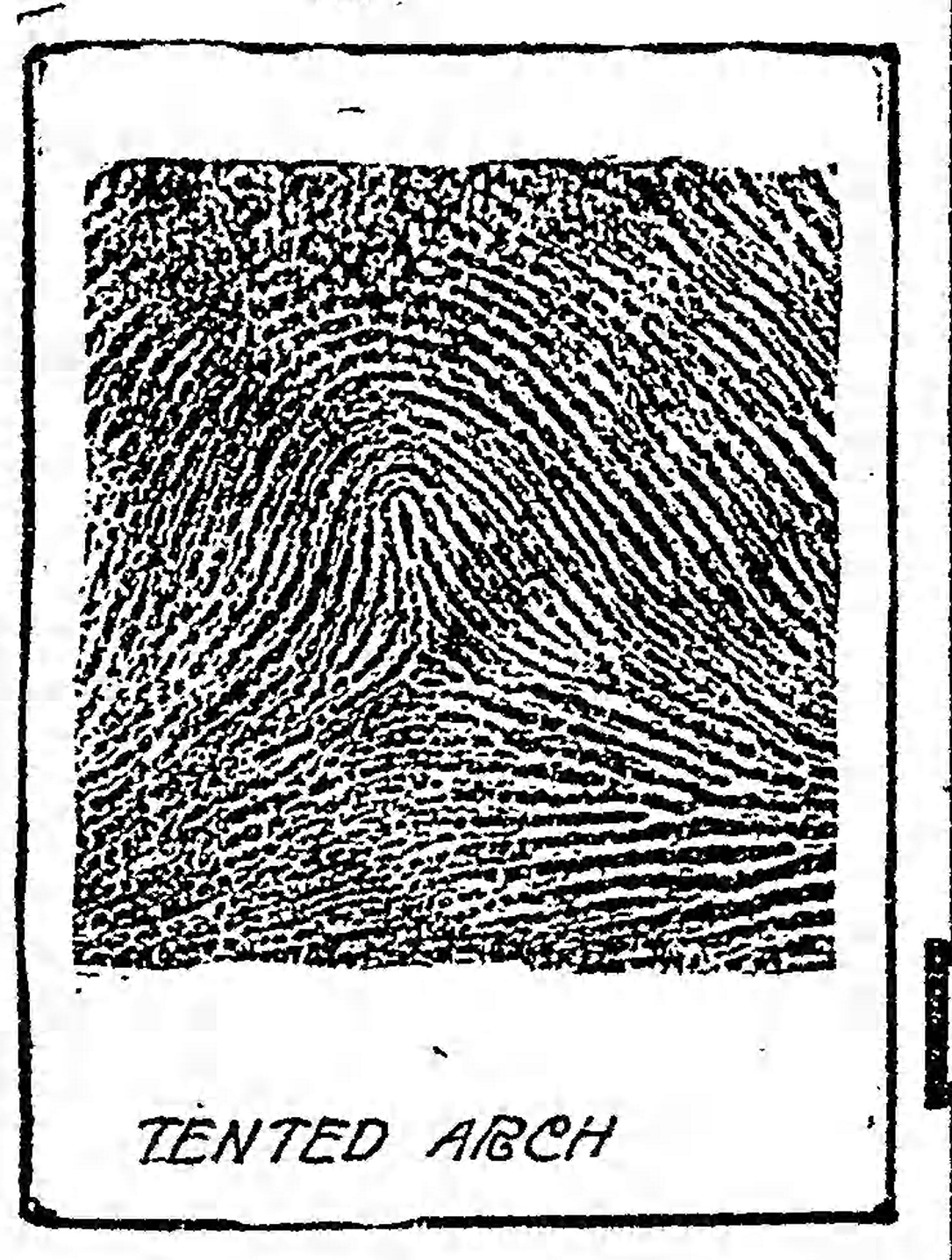

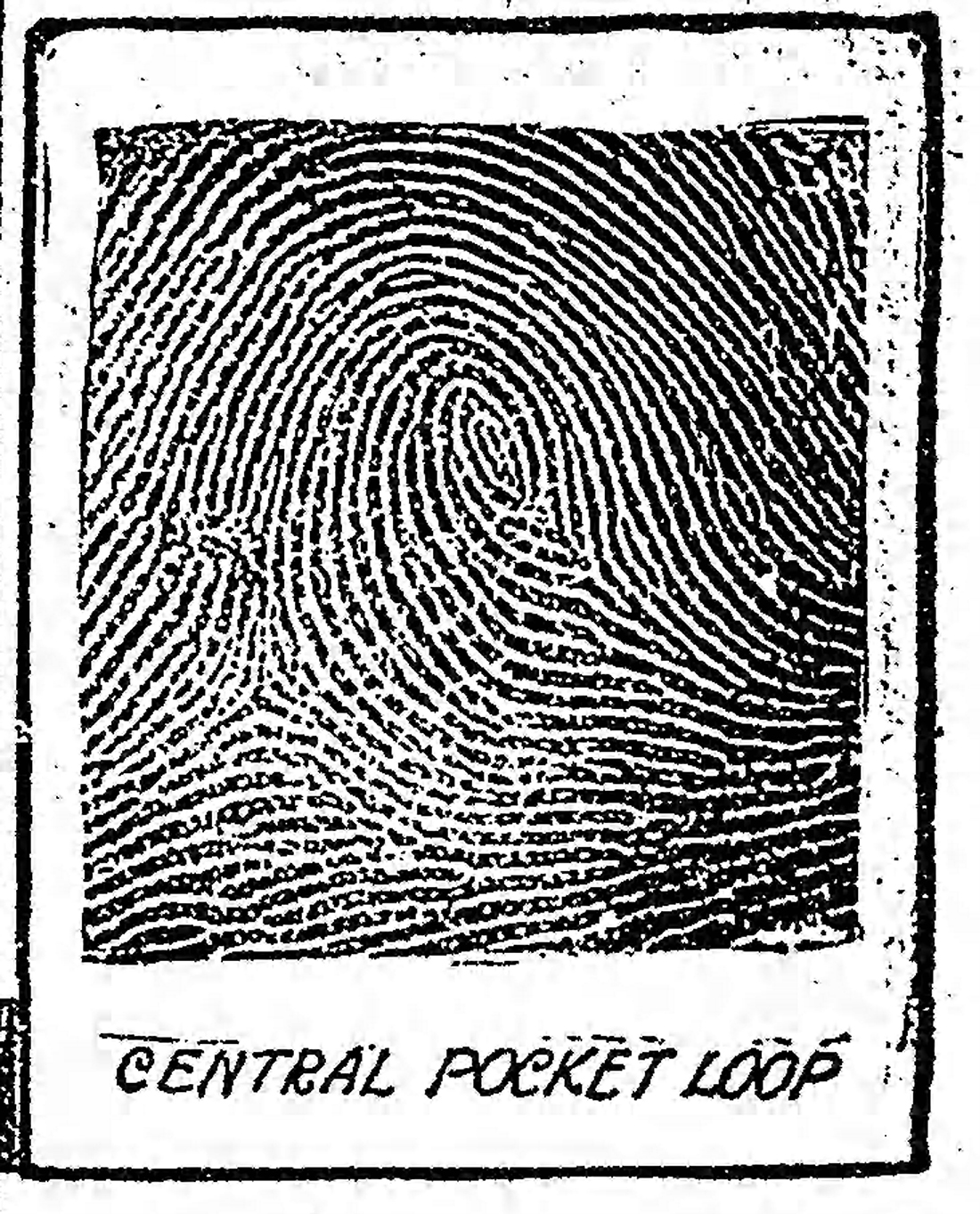

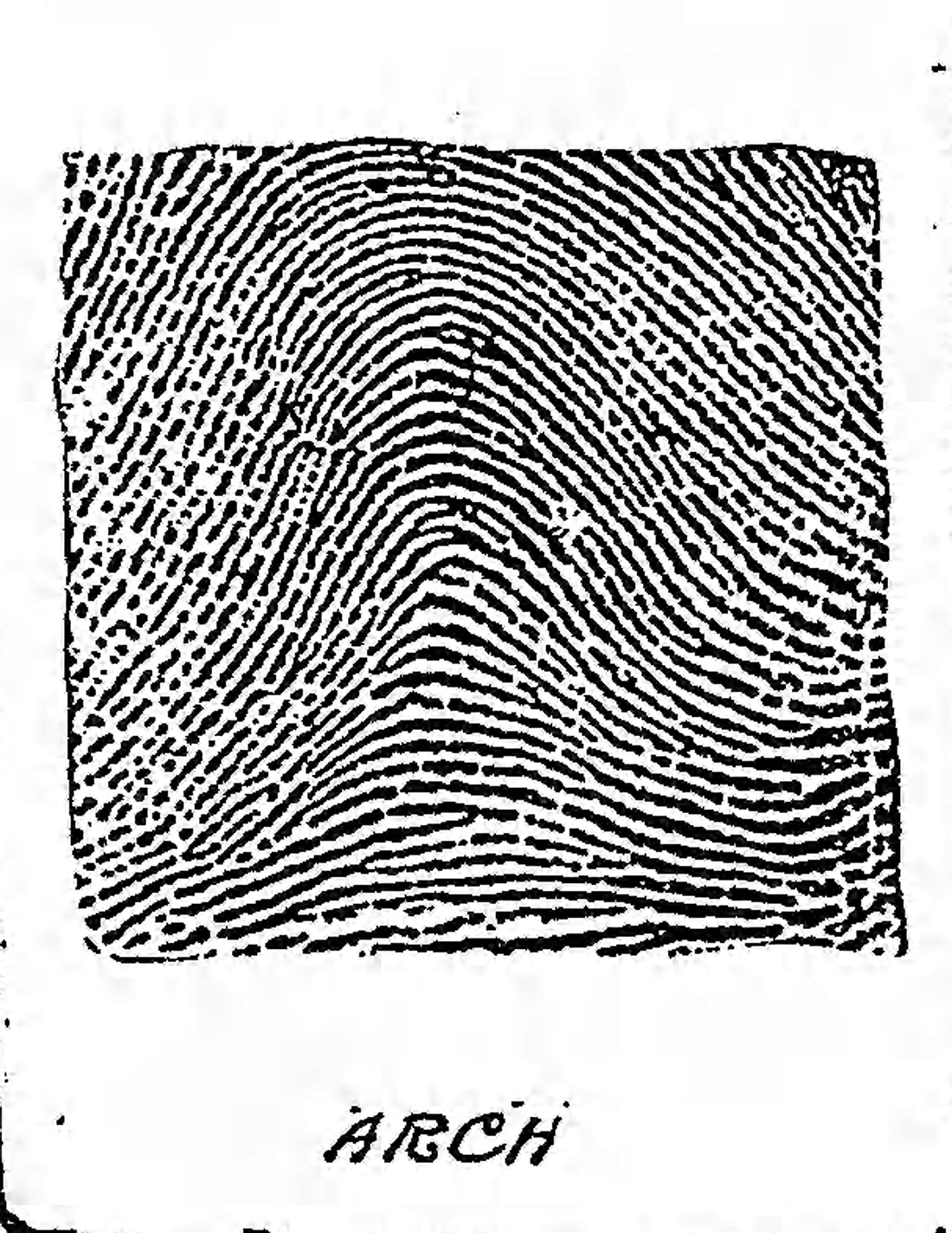

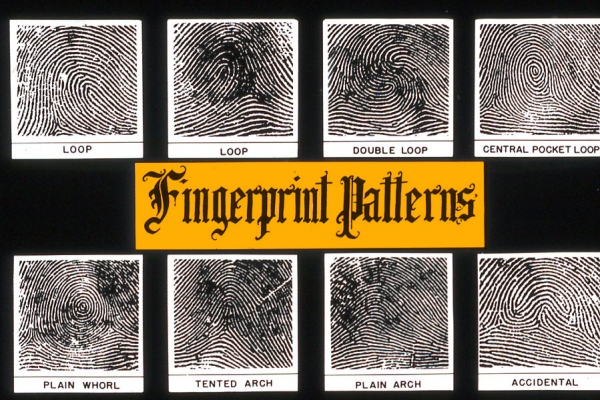

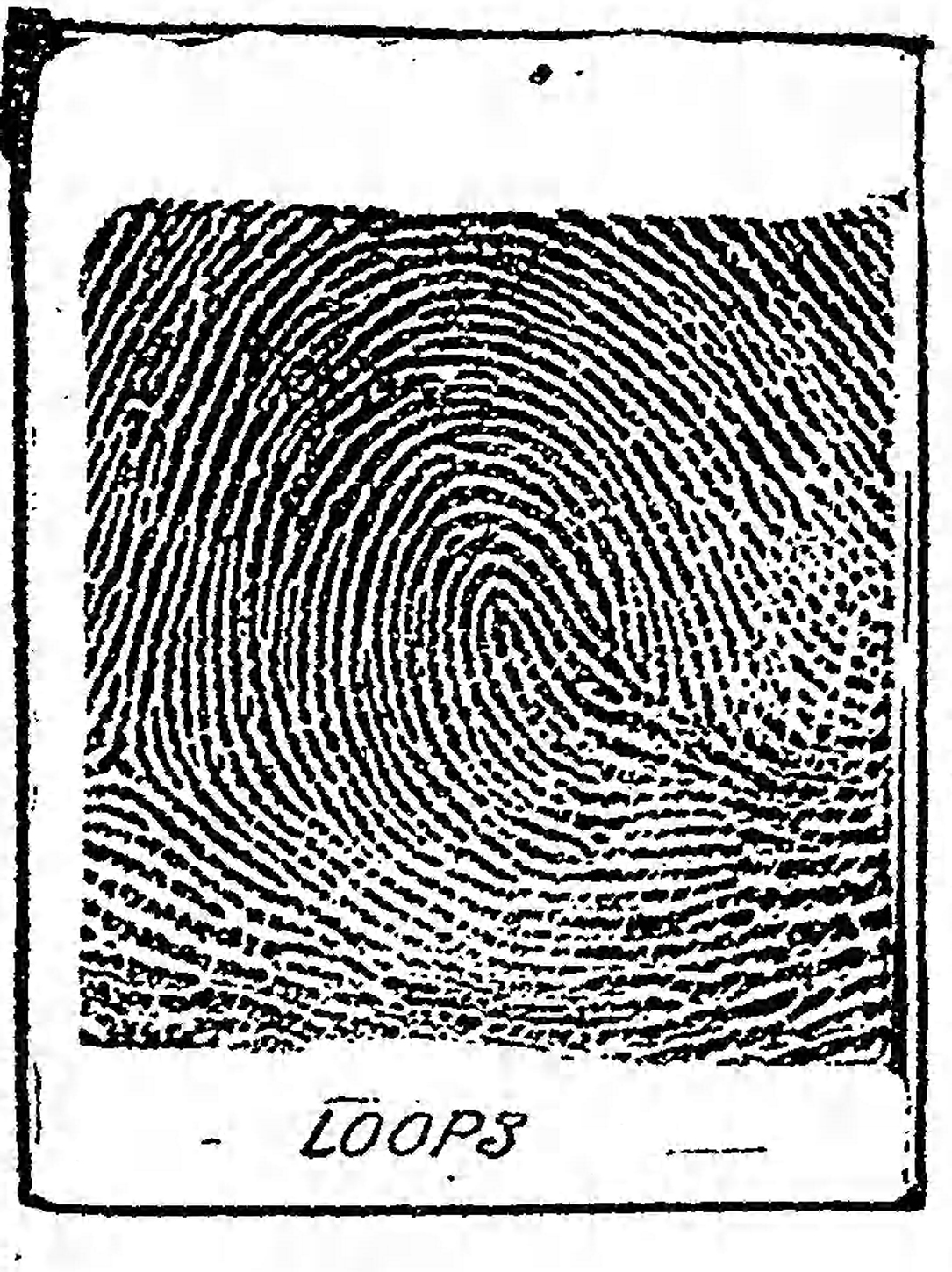

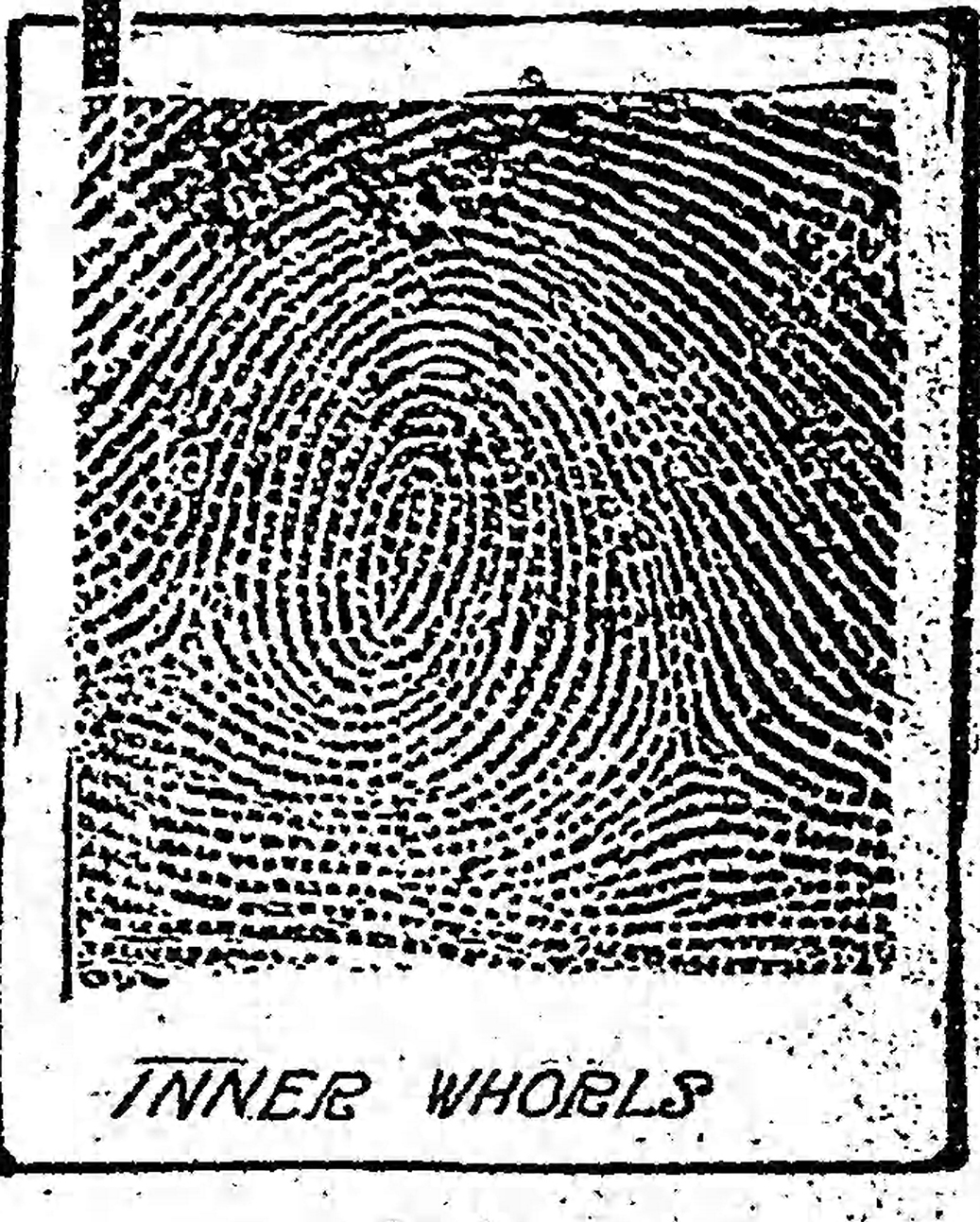

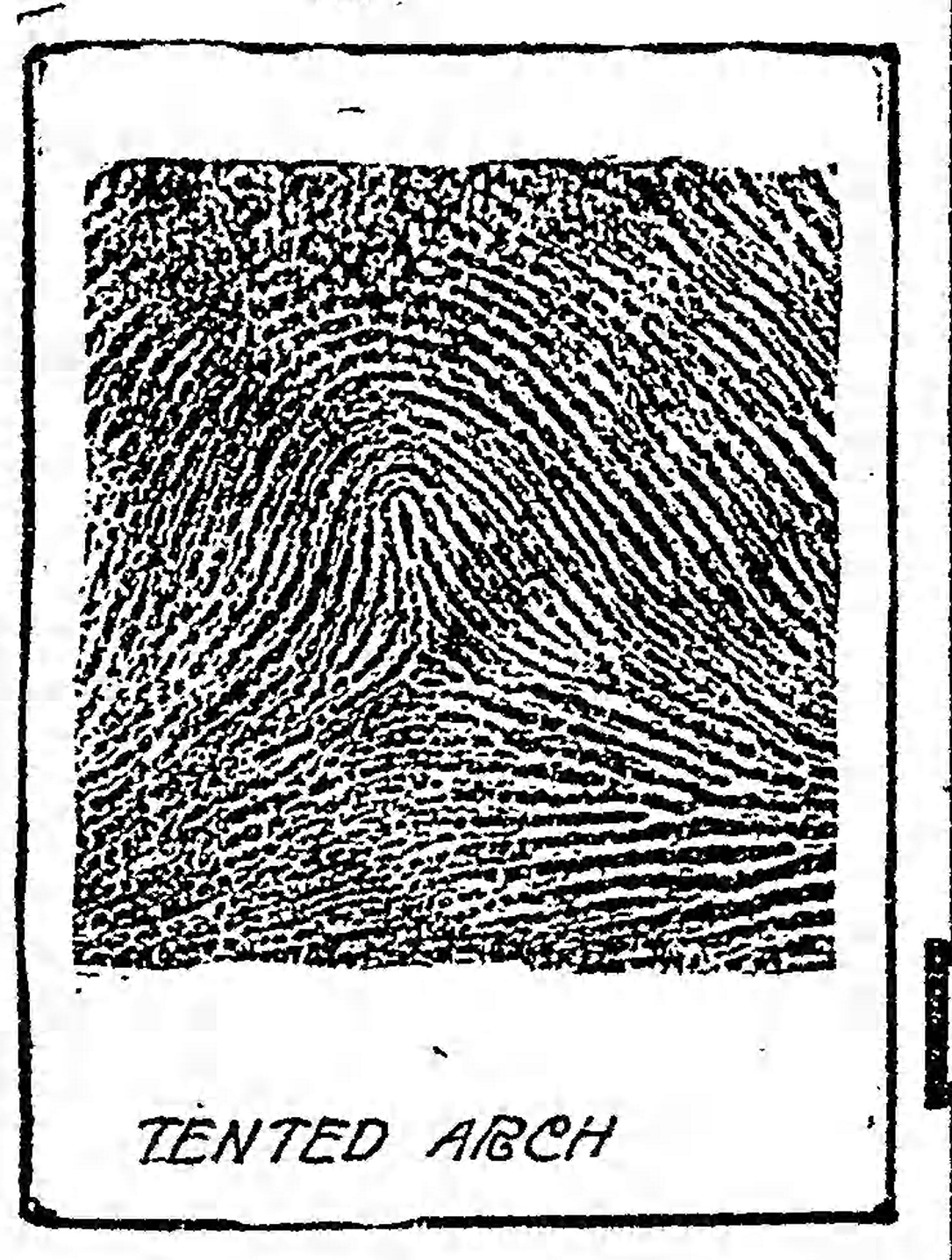

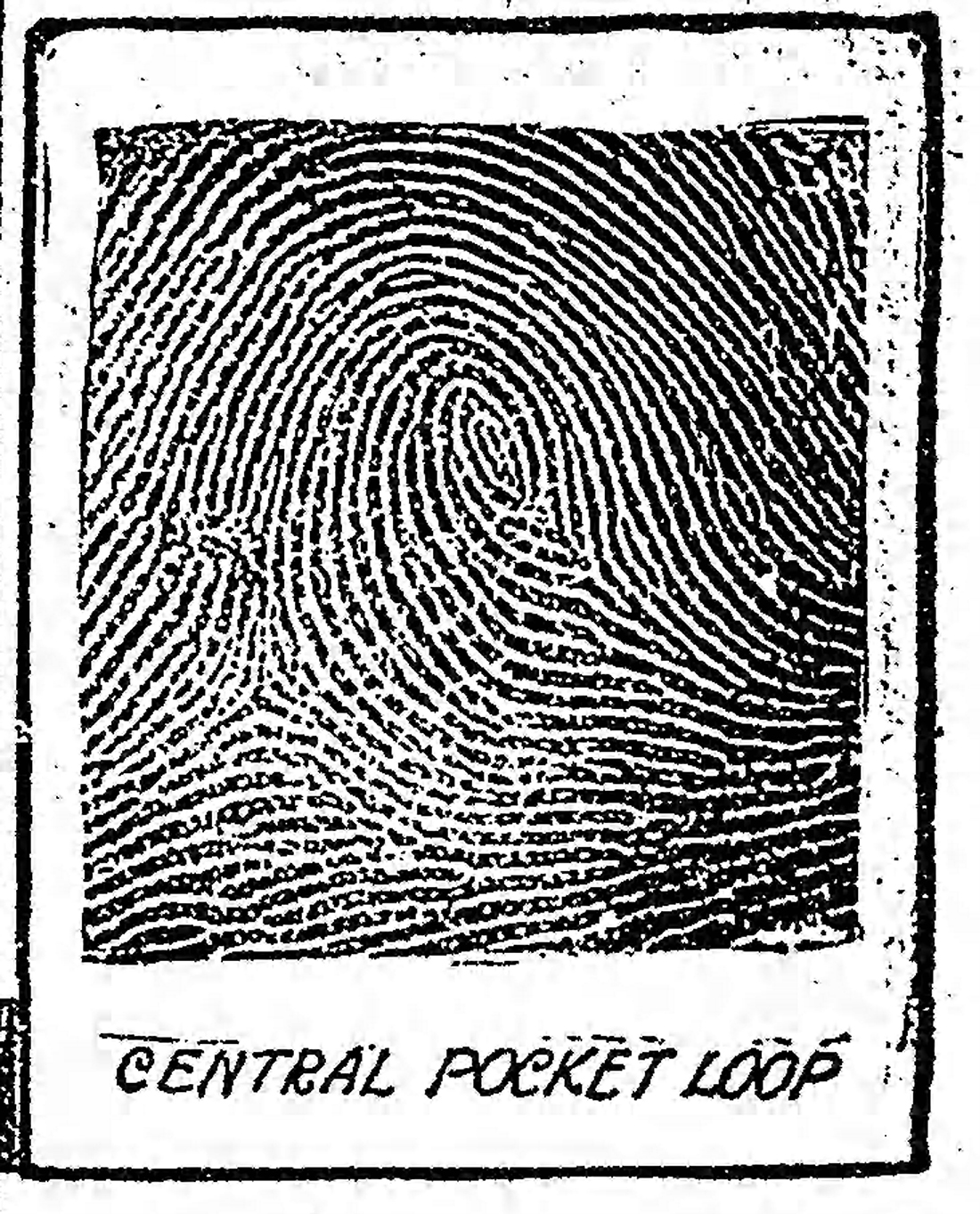

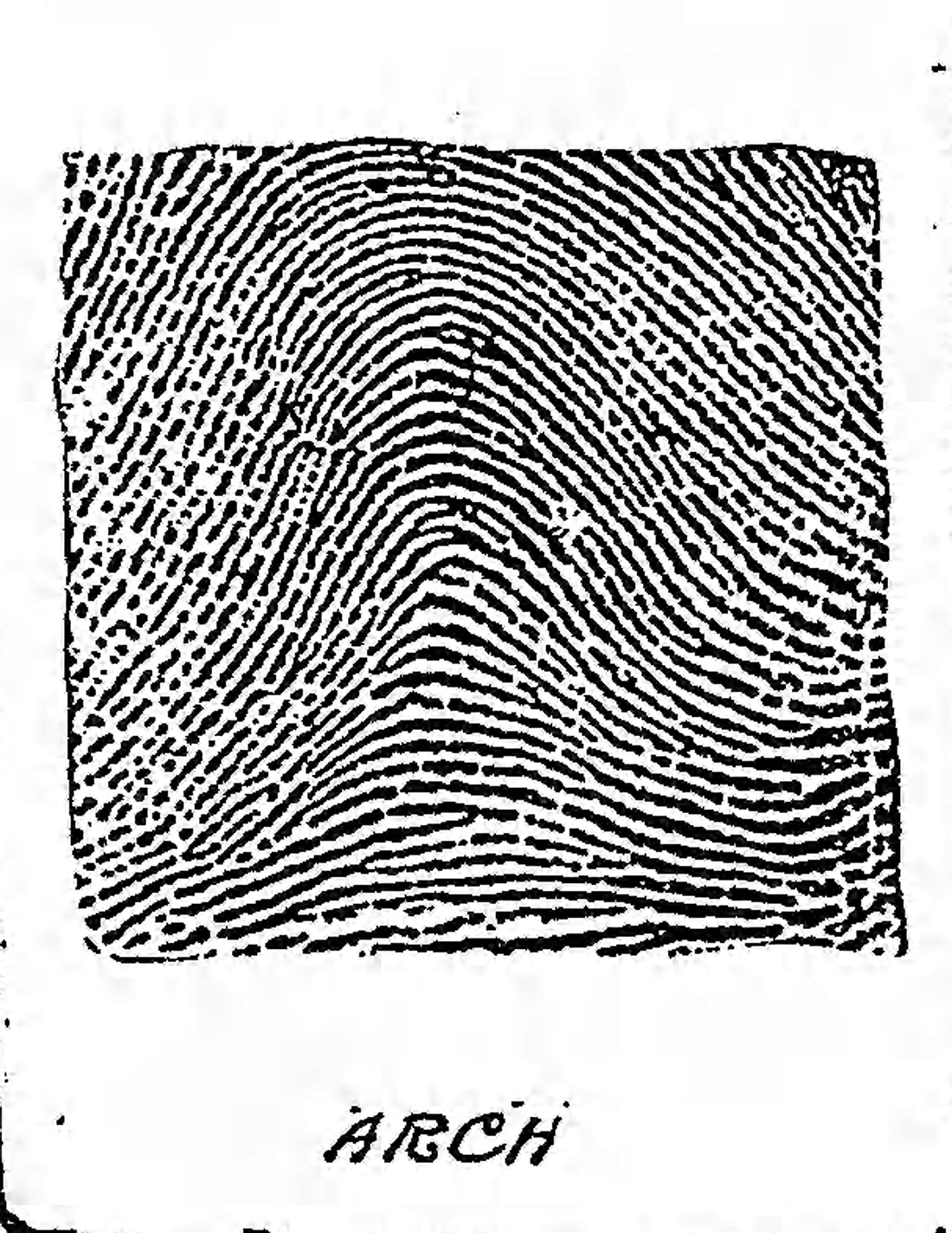

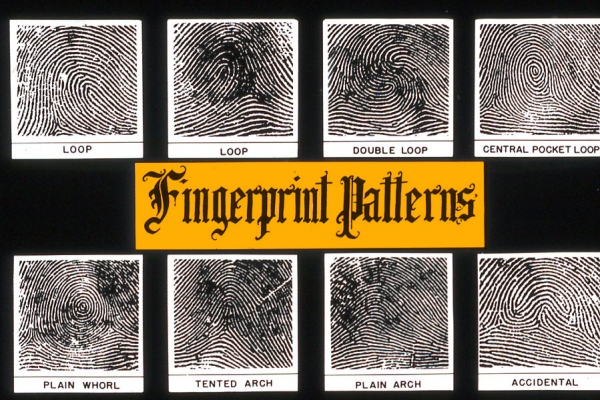

Through the study of several thousand fingerprints which he had collected while in service in India, where the government has long had them used for signatures among the lower castes of natives, Mr. Henry came to the conclusion that there were two great classes into which all fingerprints could be divided. In other words, he found that there were certain general designs upon which the patterns of all finger ends were based. These designs he named “arches,” “loops” and “whorls” and “composites.” Arches or loops occur wherever no single line of the fingertip makes a complete circle. Whorls are formed wherever a line does a nearly full circle. Composites are a sort of hybrid pattern partaking more of the nature of the whorl than of a loop. The proportions of these three classes he found to be as follows:

Arches, 5%.

Loops, 60%.

Whorls and composites, 35%

Since the number of arches was found to be inconsiderable, Mr. Henry place them in a single class with the loops. Whorls and composites were very easily associable. Thus Mr. Henry had two great natural classes and was all fingerprints could be divided.

THE 1,024 CLASSES

In every finger record, there are ten separate prints to be considered. Either one of these prints can be one of two classes, and many combinations might be formed among fingers of different classes. For instance, there might be five loops and five whorls, where there might be for loops and six whorls, and so one. The point was to find out how many classes there might be. This Mr. Henry set himself to do. If he discovered exactly the number of classes in a primary classification of his fingerprints he would be able to commence a system of filing.

One of the simplest propositions and higher mathematics is the find out the number of possible combinations among a given number of objects. A very simple formula has been worked out for this purpose. By this formula, Mr. Henry ascertained that was sets of two and ten objects there was a possibility of 1,024 combinations.

Accordingly, if a cabinet should be instructed to hold 1024 drawers, the basis of a reliable system of filing fingerprints was at hand. Now 1024 is a square of 32, so the cabinet might very conveniently be made with 32 drawers each way.

It is useless to follow the process of a finger – record filing further. It simply becomes more complicated as one goes on. It is sufficient to say that the 1024 primary classes can be subdivided by minor peculiarities of fingerprints, which Mr. Henry enumerates in his book dealing with the subject, and so the process is elastic and will accommodate any number of records. In an up-to-date print Bureau, a record can be found or filed in less than two minutes time.

ORIGINATED IN INDIA

The fingerprint system originated in India and came from that country by way of British conquest and the St. Louis exposition to Baltimore and America. In all the Eastern countries the value of fingerprints has been known from time immemorial. In China, indeed, there is a pleasant little story about an old Empress whose official seal for all the coinage of her realm was her finger impression. At any rate, for many centuries before the British took possession of India, fingerprints had been used as signatures among the lower castes.

After the Empire had been established legal difficulties with natives, who impersonate each other for the sake of fraudulently receiving, pensions became so great that some method had to be found by which one individual could be told from another. The fingerprint method, which had been observed among the natives themselves, was adopted as a peaceful solution and proved itself all that could be desired.

At first, fingerprints were used only in the government departments in India instead of signatures. Then they were taken up by the police department also. Notably, this was the case in the Bengal Bureau. Mr. E. R. Henry was then a young subaltern in the branch.

Years afterward, when Mr. Henry was appointed the chief of Scotland Yard, in London, he took his Indian method with him. When he saw the tremendous need for a systemized use of fingerprints he perfected his method of classification and filing alluded to above and gave his invention to the world.

SCOTLAND YARD THE FIRST

Scotland Yard was – of course – the first police Bureau among civilized nations to receive the benefit of the Henry method. His introduction there took place in 1897, and it was made an adjunct to the Bertillon method. Its complete adequacy for attending to the duties of identification by itself, however, soon convinced the English officials of the superfluity of the older method, so the time tried Bertillon system was dropped.

When the St. Louis exposition was opened here in 1904, the British government sent a delegation from Scotland Yard to demonstrate the effectiveness of its new system. The National Association of Chiefs of Police was in session in St. Louis at that time, and the English representative took advantage of the opportunity to address them upon the new method of identification. This is the combination of circumstances that brought the system to the United States.

Marshal Farnan of the Baltimore Police Department was one of those who heard the lecture upon the fingerprint method. He was much impressed and sought an opportunity to speak personally with the lecture. When he returned to Baltimore at the conclusion of the convention, he sought out Sgt. Casey, of the Bureau of Identification, confided to him his knowledge and delegated him to visit St. Louis and receives special lessons in this new system.

Sgt. Casey departed an unbelieving scoffer and returned an enthusiastic convert. His zeal in work has made the Baltimore Bureau one of the most favorably known in the country. The department was established here 17 December 1904 and was followed shortly by others in other big cities of the United States.

EXIT, M. BERTILLON

It has often been asked of late in police circles if the fingerprint method whatever holy supersede the Bertillon method in the United States. In case the example of Europe is followed, it most certainly will. There is now no great nation in the old country, with a single exception of France, where the Bertillon method was born, that does not use the fingerprint system exclusively.

The advantages of the fingerprint method are that it is cheaper, simpler and more reliable. The personal element of the operators of efficiency or non-efficiency does not materially alter the results. Finally, the instruments of its use are neither many nor costly. In this last point especially the Bertillon method lags far behind. Special and delicate instruments of a high cost have been installed before it can be successfully practiced.

An application of fingerprints that has caused much interest is in the detection of criminals. Suppose a burglar enters the house and leaves his fingermark upon the windowpane. No other clue was wanted by the enterprising police of today. The pain is carefully taken out and sent to the Bureau of Identification. There the prints are classified.

Then someone looks into the file, turned over a few leaves and, presto! If the burglar is an old offender, his name, photograph, criminal record and habits of living are staring one in the face. It sounds like a fairy-tale, but the experiment has been tried with complete success in England.

WHERE SCIENCE FAILED

In Baltimore not long since it was thought that this same idea could be given the application in connection with the Cunningham murder case. The search was for a killer. In the victim’s room were found the number of checks with black finger marks upon them. The police were jubilant and Sgt. Casey exalted. Here, at last, it was thought, a chance to throw the limelight on the Fingerprint Bureau. Finally, it transpired that the marks were not those of the murderer, but of an enthusiastic member of the detective corps who, in raking around among the ashes of the hearth for clues, had gotten his fingers dirty and had then picked up the bunch of checks. Science had a downfall, but even this showed us how fingerprints could be used to tell the difference between the suspect, and anyone else on the crime scene.

Whenever scientific knowledge develops unique features, it is immediately applied in a modern form for the pastime of the people. In this case, fingerprints have received an ingenious embodiment by a novelty house, which is sold a little book containing a pad of ink and some blank pages. “Flugeraphs” is to take the place of autographs. Soon, instead of the fan wanting your name and favored a bit of poetry, one will be pursued by the hobbyists in fingerprints. Smutty fingers and black males will be all the rage. Since some say, at all events. It remains to be seen.

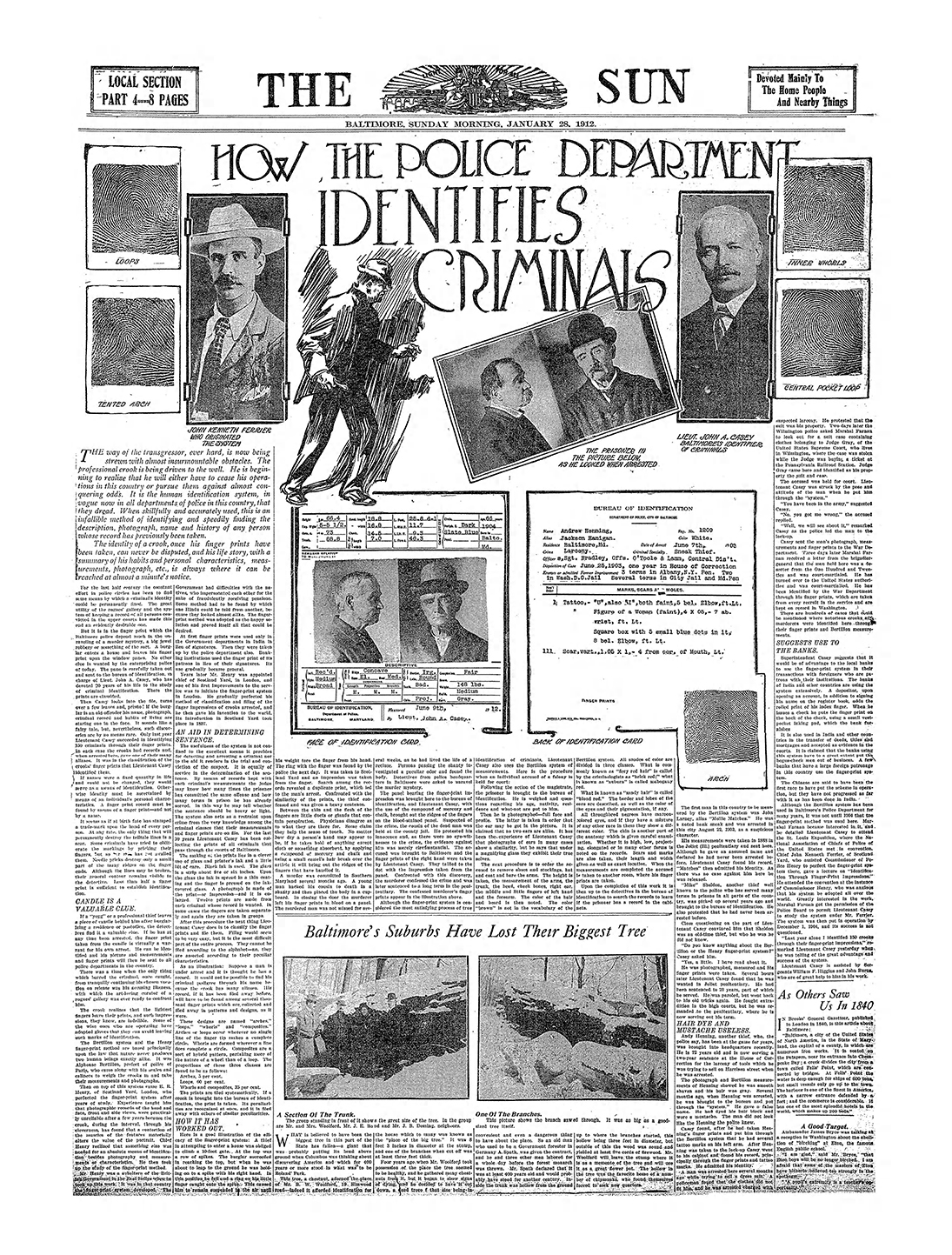

This 1912 Article on Fingerprint History is Spelled out Below

28 January 1912

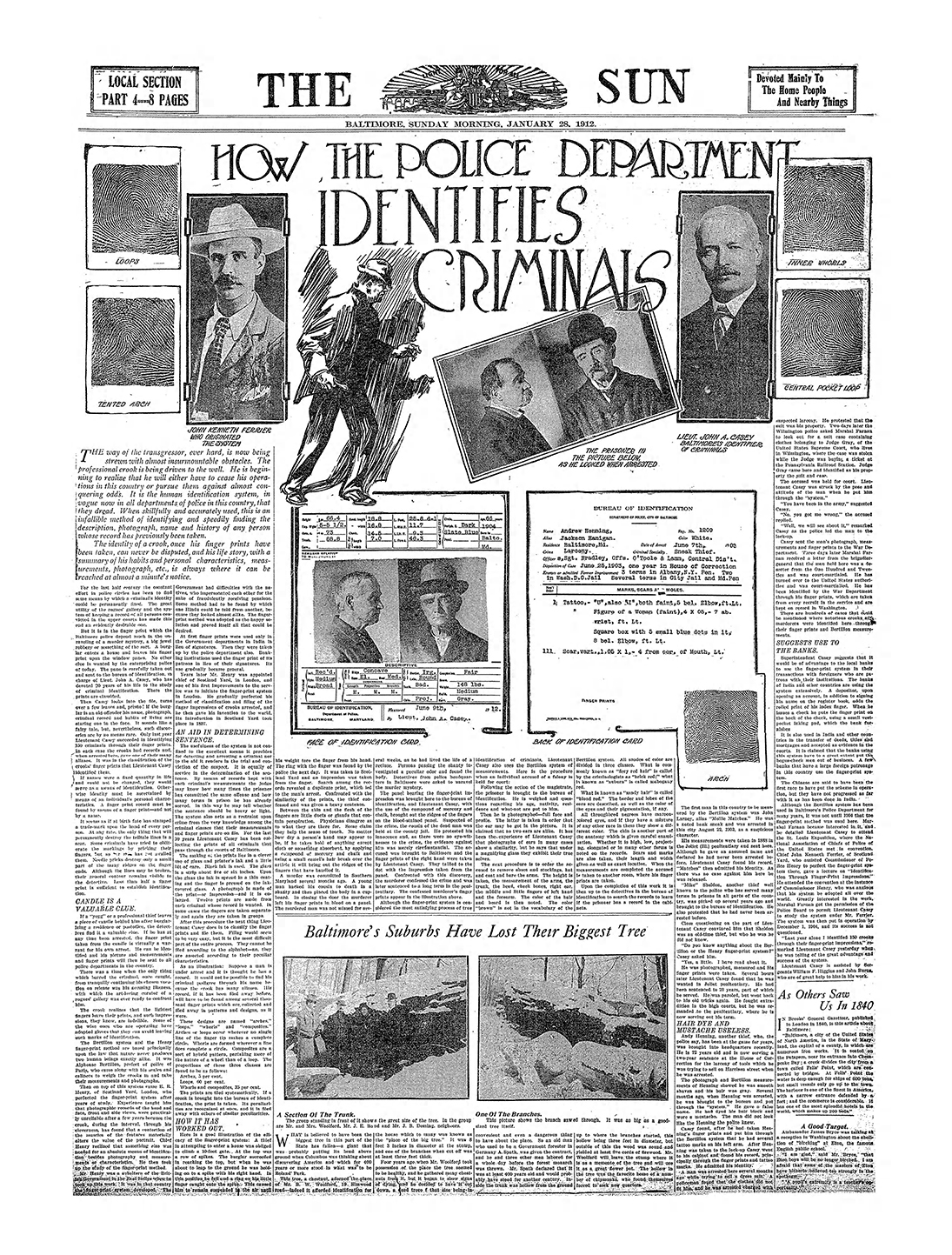

How the Police Department Identifies Criminals

As a way of the transgressor, even hard, is now being strewn with almost insurmountable obstacles. The professional crook is being driven to the wall. He is beginning to realize that he will either have to cease his operations in this country or pursue them against almost conquering odds. It is the human identification system, in vogue now in all departments of police in this country, that they dread. When skillfully and accurately used, this is an infallible method of identifying and speedily finding the description, photograph, name, and history of any person whose record has previously been taken.

The identity of a crook, once his fingerprints have been taken, can never be disputed, and his life story, with a summary of his habits and personal characteristics, measurements, photograph, etc., is always where it can be reached at almost a minute’s notice.

For the last half-century, the constant effort in police circles has been to find some means by which a criminal’s identity could be permanently fixed. The great utility of the rogue’s gallery and the system of keeping a record of all persons convicted in the upper courts has made this and evidently desirable one.

But it is in the fingerprint which the Baltimore police depend on as much as anything in the unraveling of a murder mystery, a big jewel robbery or something of the sort. A burglar enters a house and leaves his fingerprint upon the windowpane. No other clue is wanted by the enterprising police of today. The pain is carefully taken out and sent to the Bureau of identification, in charge of Lieut. John A. Casey, who has devoted 20 years of his life to the study of criminal identification. There the Prince are classified.

Then Casey investigated the file, turns over a few leaves and, presto! If the burglar is an old offender his name, photograph, criminal record and habits of living are staring one in the face. It sounds like a fairy-tale, but, nevertheless, such discoveries are by no means rare. Only last year Lieut. Casey succeeded in identifying 150 criminals to their fingerprints. In each case the crook had records and, when arrested here, gave one of their many aliases. It was in the classification of the crooks fingerprints that Lieut. Casey identified them.

If names were of fixed quality in life and could not be changed, they would serve as a means of identification. Otherwise, identity must be ascertained by means of an individual’s personal characteristics. A fingerprint record must be found by means of a fingerprint – and not by a name.

It seems as if at birth fate has stamped a trademark upon the hand of every person. At any rate, the only thing that will permanently destroy the telltale lines is a scar. Some criminals have tried to obliterate the markings by pricking their fingers, but so far that has not availed them. Needle pricks destroy only a small part of the many ridges on the finger ends. Although the lines may be broken, their general contour remains visible to the detective. Less than half a fingerprint is sufficient to establish identification.

Candle is a Valuable Clue

if a “yegg” or professional thief leaves a piece of a candle behind him after burglarizing a residence or post office, the detectives find it a valuable clue. If he has at any time been arrested, the fingerprint taken from the candle is virtually a warrant for his own arrest. He can be identified, and his picture and measurements and fingerprints will then be sent to all police departments in the country.

There was a time when the only thing which barred the criminal, once court, from tranquility containing his chosen location one release, was his accusing likeness, with which the art loving curator of the rogue’s gallery was ever ready to confront him.

The crook realizes that the latest fingers leave their prints, and such impressions, they know, or indelible. Some of the wise ones who are operating have adopted gloves that they can avoid leaving such marks of identification.

The Bertillon system and the Henry fingerprint method are based principally upon the law that nature never produces two human beings exactly alike. It was Alfonse Bertillon, Prefect of police of Paris, who came along with his scales and calipers to weigh the crooks in and take their measurements and photographs.

Then on top of this system came Sir E. R. Henry, of Scotland Yard, London, who perfected the fingerprint system after years of study. Experience taught him that photographic records of the head and face, front and side views, were practically unreliable after a few years because the crook, during the interval, through his cleverness has found that a contortion of the muscles of the features materially alters the value of the portrait. Chief Henry realized that something else was needed for an absolute means of identification besides photography and measurements or characteristics. He then took up the study of the fingerprint method.

Sir Henry was a subaltern of the British government in the East Indies when he took up this work. It was in that country the fingerprint system developed. The government had difficulties with the natives, who impersonated each other for the sake of fraudulently receiving pensions. Some methods had been found by which one Hindu could be told from another because they look almost alike. The fingerprint method was adopted as the happy solution and proved itself all that could be desired

at first fingerprints were used only in the government departments in India in lieu of signatures. Then they were taken up by the police departments also. Banking institutions use the fingerprint of its patrons in lieu of their signature. Its use gradually became general.

Years later Sir Henry was appointed the chief of Scotland Yard, and London, and one of his first improvements to the service was to initiate the fingerprint system in London. He gradually perfected his method of classification and fitting of the finger impression of crooks arrested, and he then gave his invention to the world. It’s introduction and Scotland Yard took place in 1897.

And Aid in Determining Sentence

the usefulness of the system is not confined to the excellent means it provides for detecting and arresting a criminal nor to the aid, it renders in the trial and conviction of a suspect. It is equally of service in the determination of the sentence. By means of records kept with each criminal’s measurements, the judge may know how many times the prisoner has committed the same offense and how many terms in prison he has already served. In this way he may tell others of the sentence should be a heavy or light one. The system also acts as a restraint upon crime from the very knowledge among the criminal classes that their measurements and fingerprints are on file. For the last 10 years Lieut. Casey has been collecting the Prince of all criminals that passed through the courts of Baltimore.

The making of the Prince lies and a clever use of glass and printers think and a little bit of care. The black tank is used. The glass is a strip about five or 6 inches. Upon the glass of the ink is spread in a thin coating and the finger is pressed on the Inc. covered glass. A photograph is made of the print – or impression – and is enlarged. 12 prints are made from each criminal whose record is wanted. In some cases, the fingers are taken separately and again they are taking in groups.

After this procedure the next thing Lieut. Casey does is to classify the fingerprints and file them. A filing would seem to be very easy, but it is the most difficult part of the entire process. They cannot be filed according to the alphabet – no, they are assorted according to their characteristics.

As an illustration: suppose a man is under arrest and it is thought he has a record. It would not be possible to find his criminal pedigree through his name because the crook has many aliases. His record, if it has been filed away before, will have to be found among several thousand fingerprints which are collected and filed away in patterns and designs, as it were.

These designs are named “arches,” “loops,” “whirls” and “composites.” Arches or loops occur whenever no single line of the fingertip makes a complete circle. Whirls are forms wherever a line does complete a circle. Composites are a sort of hybrid pattern, partaking more of the nature of a world than of a loop. The proportions of these three classes are found to be as follows:

arches 5%

loops 60%

whirls and composites 35%

The prints are filed systematically. If a crook is brought into the Bureau of identification, the print is taking. Its peculiarities are recognized at once, and it is filed away with the others of similar peculiarities.

How it has worked out

here is a good illustration of the if the efficiency of the fingerprint system: a thief and attempting to enter a house was obliged to climb a 10-foot gate. At the top was a row of spikes. The burglars succeeded in reaching the top, but when he was about to leap to the ground he was holding onto his bike with his right hand. In this position, he fell and a ring on his little finger caught on to the spike. This caused him to remain suspended in the air until his weight toward the finger from his and. The ring with the finger was found by the police the next day. It was taken a Scotland Yard and an impression was taken from the finger. Search among the records revealed a duplicate print, which led to the man’s arrest. Confronted with the similarity of the Prince, the thief confessed and was given a heavy sentence.

Between the skin and the flesh of the fingers are little ducks or glands that contain perspiration. Physicians disagree as to what they are there for. Some claim they help the sense of touch. No matter how dry a person’s hands may appear to be, if he takes hold of anything except cloth or something absorbent, by applying a compound of mercury and chalk and using a small camel hair brush over the article it will bring out the ridges of the fingers that have handled the object.

A murder was committed in southern Maryland several months ago. A young man acts his cousin to death in Ashanti and then placed the body and the covered. In closing the door, the murderer left his fingerprints and blood on a panel. The murdered man was not missed for several weeks, as he had lived the life of a recluse. Persons passing the shanty investigated a peculiar odor and found the body. Detectives from the police headquarters in Baltimore were asked to unravel the murder mystery.

The panel bearing the fingerprint impression was brought here to the Bureau of identification, and Lieut. Casey, with the use of the compound of mercury and chalk, brought out the ridges of the fingers on the bloodstain panel. Suspected of the crime, the cousin of the dead man was held at the county jail. He protested his innocence and, as there were no eyewitnesses to the crime, the evidence against him was merely circumstantial. The accused was brought to Baltimore and the fingerprints of the right hand were taken by Lieut. Casey. They matched to the dot with the impressions taken from the panel. Confronted with this discovery, the murderer confessed the crime and was later sentenced to a long-term in the penitentiary. The confessed murders fingerprints appear in illustrations above. Although the fingerprint system is considered the most satisfying process of true identification of criminals, Lieut. Casey also uses the Bertillon system of measurements. Here is the procedure when an individual accused of a felony is held for court:

following the action of the magistrate, the prisoner is brought to the Bureau of identification. He is weighed and questions regarding his age, nativity, residence, and whatnot are put to him.

Then he is photographed – full face and profile. The latter is taken in order that the ear may be got in the picture. It is claimed that no two years are alike. It has been the experience of Lieut. Casey that photographs of years in many cases show a similarity, but he says that under a magnifying glass they exhibit their true selves.

The next procedure is to order the accused to remove shoes and stockings, hat and coat and bear the arms. The height is taken, the measurement of the arms, the trunk, the head, cheekbones, right here the middle and little fingers of left hand and the forearm. The color of the hair and beard is then noted. The color “brown” is not in the vocabulary of the Bertillon system. All shades of color are divided into three classes. What is commonly known as “fiery red hair” is called by the criminologist as “brick red;” what is known as “Auburn” is called mahogany red.

What is known as “Sandy here” is called “blonde red.” The border and logos of the ears are described. As well as the color of the eyes and their pigmentation, if any.

All thoroughbred Negroes have maroon colored eyes, and if they have a mixture of any other race in them they show a different color. The chin is another part of the anatomy was his given careful examination. Whether it is high, low, projecting, elongated or in many other forms is noted on the records. Scars and marks are also taken. Their length and width are given as well as exact locations. When the measurements are combined the accused is taken to another room, where his fingerprints are taken.

Upon the completion of this work, it is then up to the detectives in the Bureau of identification to search the records to learn if the prisoner has a record in the cabinets.

The first man in his country to be measured by the Bertillon system was John Larney, alias “Molly matches.” He was a noted bank snake and was arrested in this city 22 August 19 disarray, as a suspicious character.

His measurements were taken in 18 eight and Juliet Illinois penitentiary and sent here. Although he gave an assumed name and declared he had never been arrested before, Lieut. Casey found his record. “Matches” then admitted his identity. As there was no case against him here he was released.

“Mike” Sheldon, another thief well known to the police who has served many terms in prisons in all parts of the country, was picked up several years ago and brought to the Bureau of identification. He also protested that he had never been arrested before.

Close questioning on the part of Lieut. Casey convinced him that Sheldon was an old-time thief, but who he was he did not know.

“Do you know anything about the Bertillon system or the Sir Henry fingerprint system?” Casey asked him.

“Yes, a little. I’ve read about it. He was photographed, measured and his fingerprints were taken. Several hours later Lieut. Casey found that he was wanted and Juliet penitentiary. He had been sentenced to 20 years, part of which he served, he was paroled, but went back to his old tricks again. He fought extradition in the high courts, but he was remanded to the penitentiary, where he is now serving out his term.

Hair Dye and Mustache Useless

Andy Henning another thief, who, the police say, has been at the game for years, was brought into headquarters recently. He is 72 years old and is now serving a two-year sentence at the House of corrections for the larceny of tools which he was trying to sell on Harrison Street when he was arrested.

The photograph and Bertillon system of measurements of Henning showed he was smooth shaven and his hair was gray. Several months ago, when Henning was arrested, he was brought to the Bureau and put through the system. He gave a false name. He had dyed his hair black and wore a mustache. The man did not look like the Henning the police know.

Casey found after he had taken Henning’s fingerprints and put him through the Bertillon system that he had several tattoo marks on his left arm. After Henning was taken to the lockup Casey went to his cabinet and found his record, principally through the fingerprints and tattoo marks. He admitted his identity.

A man was arrested here several months ago while trying to sell a dress suit. A policeman found that the close did not fit him, and he was arrested and charged with suspected larceny. He protested that the suit was his property. Two days later the Wilmington police asked to Marshall Farnan to lookout for a suitcase containing close belonging to Judge Gray, of the United States Supreme Court, who lives in Wilmington, where the case was stolen while the judge was buying a ticket at the Pennsylvania Railroad station. Judge Gray came here and identified as his property the suit and case.

The accused was held for court. Lieut. Casey was struck by the pose and attitude of the man when he put him through the system.

“You have been in the Army,” suggested Casey.

“No, you got me wrong,” the accused replied.

“Well, we will see about that,” remarked Casey as the police led the man to lockup.

Casey sent them as photograph measurements and fingerprints to the war department. Three days later Marshall Farnan received the letter from the Brig. Gen. that the man held here was a deserter from the one hundred and twenties and was court-martialed. He was turned over to United States authorities and was court-martialed. He has been identified by the war department to his fingerprints, which are taken from every recruit in the service and are kept on record in Washington.

There are hundreds of cases that could be mentioned where notorious crooks and murderers were identified here through their fingerprints and the Bertillon system of measurements.

Suggest Use to Banks

superintendent Casey suggests that it would be of advantage to the local banks to use the fingerprint system and their transactions with foreigners who are patrons with their institutions. The banks of India and other countries are using the system extensively. A depositor, upon opening an account, in addition to signing his name on the register book, adds the role print of his index finger. When he issues a check, he puts the fingerprint on the back of the check, using a small vest pocket inking pad, which the bank furnishes.

It is also used in the and other countries in the transfer of deeds, titles, and mortgages and accepted as evidence in court. It is claimed that the banks using this system have to a great extent put the bogus check men out of business. A few banks that have a large foreign patronage in this country use the fingerprint system.

The Chinese are said to have been the first race to have put the scheme in operation, but they have not progressed as far with it as has been done in India.

Although the Bertillon system has been used in Baltimore’s Police Department for many years, it was not until 1904 that the fingerprint method was used here. Marshall Farnan became interested in it, and he detailed Lieut. Casey to attend the St. Louis exposition, where the National Association of Chiefs of police of the United States met his convention. Chief John Kenneth Ferrier, of Scotland Yard, who assisted Commissioner of police Sir Henry to perfect the fingerprint system there, gave a lecture on “identification to fingerprint impression.” He attended the convention at the instance of Commissioner Henry, who was anxious that his system is adopted all over the world. Greatly interested in the work, Marshall Farnan got the permission of the police board to permit Lieut. Casey to study the system under Mr. Ferrier. The system was then put in operation by 1 December 1904, and its success is not questioned.

“Last year alone we identified 150 crooks through their fingerprint impressions,” remarked Lieut. Casey yesterday when he was telling of the great advantage and success of the system.

Lieut. Casey is assisted by sergeants William F Higgins and John Burns, who are of great help to him in his work.

As others saw us in 1840

In Brooks General Gazette, published in London in 1840, is this article about Baltimore:

“Baltimore, a city of the United States of North America, and the state of Maryland, the capital of the country, in which are numerous Ironworks. It is seated on the Patapsco, near the entrance into the Chesapeake Bay; a creek divides the city from a town called Fells Point, which are connected by bridges. At Fells point the water is deep enough for ships of 600 tons but small vessels only go up to the town. The harbor is one of the finest in America, with a narrow entrance defended by a Fort; and the commerce is considerable. It has one of the most splendid hotels in the world, which makes up 200 beds”

Courtesy of Lt Robert Wilson

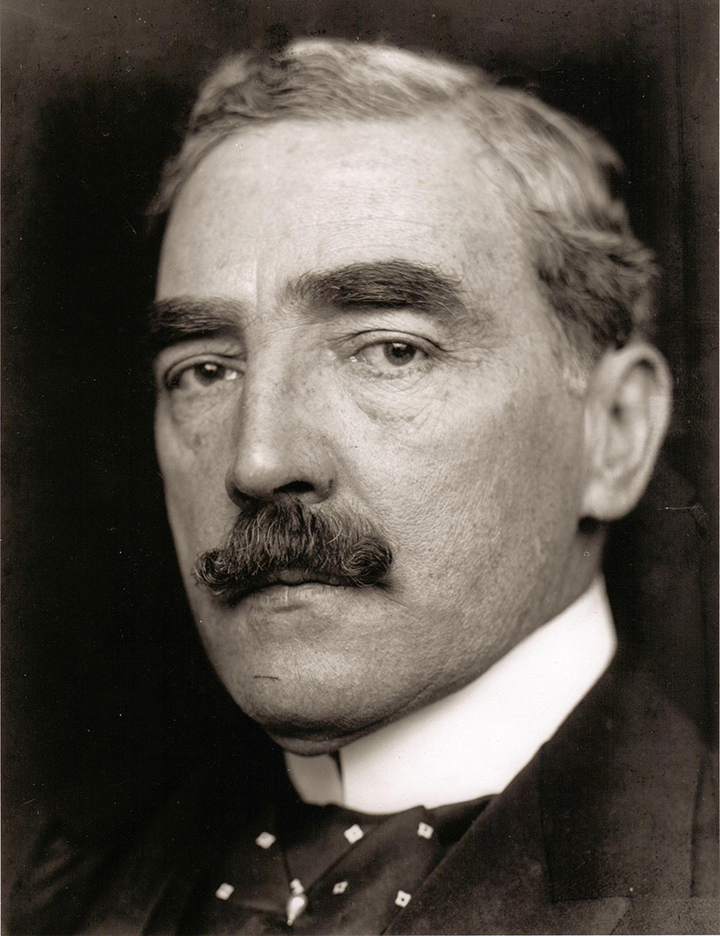

Sir Edward Richard Henry, 1st Baronet

(26 July 1850 – 19 February 1931)

Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis

(Head of the Metropolitan Police of London)

1903 to 1918.

Known for

The introduction of K9 Dogs for use with Police, and Fingerprinting for the purposes of identifying criminals. Sir Henry has had a tremendous amount of difference in the way the world fights crime, and oddly enough two of his inventions/findings were used and perfected in Baltimore City, Baltimore Maryland.

Early Life

Sir Henry was born in Shadwell, London to Irish parents; his father was a doctor. He studied at St Edmund's College, Ware, Hertfordshire, and at sixteen he joined Lloyd's of London as a clerk.

He meanwhile took evening classes at University College, London to prepare for the entrance examination of the Indian Civil Service.

Early service in India

On 9 July 1873, he passed the Indian Civil Service Examinations and was 'appointed by the (Her Majesty's) said [Principal] Secretary of State (Secretary of State for India) to be a member of the Civil Service at the Presidency of Fort William in Bengal.'

On 28 July 1873 he married Mary Lister at St. Mary Abbots, the Parish Church of Kensington, London. Mary's father, Tom Lister was the Estate Manager for the Earl of Stamford.

In September 1873 Edward Henry set sail for India. He arrived in Bombay and traveled across India arriving at Allahabad on 22 October 1873 to take up the position of Assistant Magistrate Collector within the Bengal Taxation Service.

He became fluent in Urdu and Hindi. In 1888, he was promoted to Magistrate-Collector. In 1890, he became aide-de-camp and secretary to the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal and Joint Secretary to the Board of Revenue of Bengal.

On 24 November 1890, as a widower, he remarried, by marrying Louisa Langrishe Moore.

Inspector-General of Police

On 2 April 1891, Henry was appointed Inspector-General of Police of Bengal. He had already been exchanging letters with Francis Galton regarding the use of fingerprinting to identify criminals, either instead of or in addition to the anthropometric method of Alphonse Bertillon, which Henry introduced into the Bengal police department.

The taking of fingerprints and palm prints had been common among officialdom in Bengal as a means of identification for 40 years. Having been introduced by Sir William Herschel, it was not used by the police, and there was no system of simple sorting to allow rapid identification of an individual print (although the classification of types was already used).

Between July 1896 and February 1897, with the assistance of Sub-Inspectors Azizul Haque and Hemchandra Bose, Henry developed a system of fingerprint classification enabling fingerprint records to be organized and searched with relative ease. It was Haque who was primarily responsible for developing a mathematical formula to supplement Henry's idea of sorting in 1,024 pigeon holes based on fingerprint patterns. Years later, both Haque and Bose, on Henry's recommendation, received recognition by the British Government for their contribution to the development of fingerprint classification.

In 1897, the Government of India published Henry's monograph, Classification, and Uses of Fingerprints. The Henry Classification System quickly caught on with other police forces, and in July 1897 Victor Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin, the Governor-General of India, decreed that fingerprinting should be made an official policy of the British Raj. This classification system was developed to facilitate orderly storage and faster search of fingerprint cards called ten-print cards. It was used when the ten-print cards were cataloged and searched manually and not digitally. Each ten-print card was tagged with attributes that can vary from 1/1 to 32/32.

In 1899, the use of fingerprint experts in court was recognized by the Indian Evidence Act.

In 1898, he was made a Companion of the Star of India (CSI).

In 1900, Henry was seconded to South Africa to organize the civil police in Pretoria and Johannesburg.

In the same year, while on leave in London, Henry spoke before the Home Office Helper Committee on the identification of criminals on the merits of Bertillonage and fingerprinting.

Assistant Commissioner (Crime)

In 1901, Henry was recalled to Britain to take up the office of Assistant Commissioner (Crime) at Scotland Yard, in charge of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID).

On 1 July 1901, Henry established the Metropolitan Police Fingerprint Bureau, Britain's first. Its primary purpose was originally not to assist in identifying criminals, but to prevent criminals from concealing previous convictions from the police, courts, and prisons.

However, it was used to ensure the conviction of burglar Harry Jackson in 1902 and soon caught on with CID. This usage was later cemented when fingerprint evidence was used to secure the convictions of Alfred and Albert Stratton for murder in 1905. Like DNA today has cleared some formerly convicted so too has Fingerprints in the early 1900's.

Henry introduced other innovations as well. He bought the first typewriters to be used in Scotland Yard outside the Registry, replacing the laborious hand-copying of the clerks.

In 1902, he ran a private telegraph line from Paddington Green Police Station to his home and later replaced it with a telephone in 1904.

Commissioner

On Sir Edward Bradford's retirement in 1903, Henry was appointed Commissioner, which had always been the Home Office's plan.

Henry is regarded as one of the great Commissioners. He was responsible for dragging the Metropolitan Police into the modern day, and away from the class-ridden Victorian era. However, as Commissioner, he began to lose touch with his men, as others before him had done.

He continued with his technological innovations, installing telephones in all divisional stations and standardizing the use of police boxes, which Bradford had introduced as an experiment but never expanded upon.

He also soon increased the strength of the force by 1,600 men and introduced the first proper training for new constables.

In 1905, Henry was made a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (CVO) and the following year was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (KCVO). In 1910 he was made Knight Commander of the Bath (KCB). In 1911, he created a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (GCVO) after attending the King and Queen at the Delhi Durbar.

He was also a Grand Cross of the Dannebrog of Denmark, a Commander of the Légion d'Honneur of France, and a member of the Order of Vila Viçosa of Portugal and the Order of St. Sava of Yugoslavia, as well as an Extra Equerry to the King.

Henry was awarded the King's Police Medal (KPM) in the 1909 Birthday Honours.

Attempted Assassination

On Wednesday 27 November 1912, while at his home in Kensington, Henry survived an assassination attempt by one Alfred Bowes (also reported as "Albert" Bowes), a disgruntled cab driver whose license application had been refused.

Bowes fired three shots with a revolver when Sir Edward opened his front door: two missed, and the third pierced Sir Edward's abdomen, missing all the vital organs. Sir Edward's chauffeur then tackled his assailant. Bowes faced a life sentence for attempted murder

Sir Edward appeared at court and followed a humane tradition of pleading for leniency for his attacker, stating that Bowes had wanted to better himself and earn a living to improve the life of his widowed mother. Bowes was sentenced to 15 years' penal servitude, but Sir Edward maintained an interest in his fate and eventually paid for his passage to Canada for a fresh start when Bowes was released from prison in 1922

Sir Edward never really recovered from the ordeal, and the pain of the bullet wound recurred for the rest of his life.

First World War

Henry would have retired in 1914, but the outbreak of the First World War convinced him to remain in office, as his designated successor, General Sir Nevil Macready, was required by the War Office, where he was Adjutant-General. He remained in office throughout the war.

The end of Henry's career came about due to the police strike of 1918. Police pay had not kept up with wartime inflation, and their conditions of service and pension arrangements were also poor.

On 30 August 1918, 11,000 officers of the Metropolitan Police and City of London Police went on strike while Henry was on leave. The frightened government gave in to almost all their demands. Feeling let down both by his men and by the government, whom he saw as encouraging trade unionism within the police (something he vehemently disagreed with), Henry immediately resigned on 31 August. He was widely seen as a scapegoat for political failures.

Later life

On 25 November 1918, Henry created a baronet, and in 1920 he and his family retired to Cissbury, near Ascot, Berkshire.

He continued to be involved in fingerprinting advances and was on the committee of the Athenaeum Club and the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, as well as serving as a Justice of the Peace for Berkshire. He died at his home in 1931 of a heart attack, aged 80.

The Baronetcy became extinct, since his only son (he also had two daughters), Edward John Grey Henry, had died in 1930 at the age of 22.

His grave lay unattended for many years. In April 1992, it was located in the cemetery adjoining All Souls Church, South Ascot by Metropolitan Police Fingerprint Expert Maurice Garvie & his wife, Janis. After a presentation by Maurice Garvie to The Fingerprint Society on the Life & Times of Sir Edward, the Fingerprint Society agreed to the funding and restoration of the grave which was completed in 1994. In the Metropolitan Police Fingerprint Bureau Centenary Year, 2001, at the suggestion of Maurice Garvie, English Heritage in honor of Sir Edward Henry. They went to his former home on his former London home, 19 Sheffield Terrace, Kensington, W.8 and placed to be unveiled a Blue Plaque. The year before, following an approach by Maurice Garvie, Berkshire County Council revealed on Sir Edward's retirement home 'Cissbury' a Berkshire County Council Heritage a Green Plaque.

29 April 1896

A system of Measuring Criminals

Wednesday, 29 April 1896 - Mr. G. M. Porteous, agent of the Bertillon system of measuring criminals, appeared before Baltimore’s Board of commissioners yesterday and said he would begin in a few days to put up the apparatus for the introduction of this system in the police department for this city [Baltimore]. The apparatus and the photo gallery for taking the portraits for the Rogues Gallery will be in the room now occupied by the city Commissioner, located on the northwest corner of City Hall, on the first floor. Mr. Harry Bruff, the newly appointed assistant secretary to the board, will be in charge of the apparatus.

Baltimore City Police History – Baltimore Police Department becomes the First agency in the United States to use the system to catalog criminals I have seen other sites (written in modern times) use years as dates, but none of them name, names, here we have newspaper articles that were written in 1904, 1905, and 1907… that not only provide dates, but gives the names of who did the fingerprinting, who was fingerprinted, and for what. So we know on 26 November 1904, Sgt. Casey finger-printed John Randles on a theft charge. We also know from those articles that Baltimore’s fingerprint system of identification “The fingerprint system of identification was inaugurated [Wednesday] 7 December last [1904]” in the Baltimore Police Department’s Bureau of Identification.” From other articles giving estimated dates say, “Sometimes” when they said, “sometime after the St. Louis World's Fair, the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) created America's first national fingerprint repository, called the National Bureau of Criminal Identification.” Baltimore had already established a From one of the other sites, http://onin.com/fp/fphistory.html

1904

The use of fingerprints began in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in Kansas, and the St. Louis Police Department. They were assisted by a Sergeant from Scotland Yard who had been on duty at the St. Louis World's Fair Exposition guarding the British Display. “Sometimes” after the St. Louis World's Fair, the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) created America's first national fingerprint repository, called the National Bureau of Criminal Identification.

During World War 1 immigrant aliens were registered at the Central police station February 1918 one of the aliens being fingerprinted by Sergeant Manning. Others in the photo are Lieutenant Klinefelter, Sergeant Barry, patrolmen Zimmerman, Lentz, Forrest, and Bradbury.

POLICE INFORMATION

Copies of: Your Baltimore Police Department Class Photo, Pictures of our Officers, Vehicles, Equipment, Newspaper Articles relating to our department and or officers, Old Departmental Newsletters, Lookouts, Wanted Posters, and or Brochures. Information on Deceased Officers and anything that may help Preserve the History and Proud Traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to Honor the fine men and women who have served with Honor and Distinction at the Baltimore Police Department.

Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. follow us on Twitter @BaltoPoliceHist or like us on Facebook or mail pics to 8138 Dundalk Ave. Baltimore Md. 21222

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll

You May Like