Baltimore City Police

Call Box History

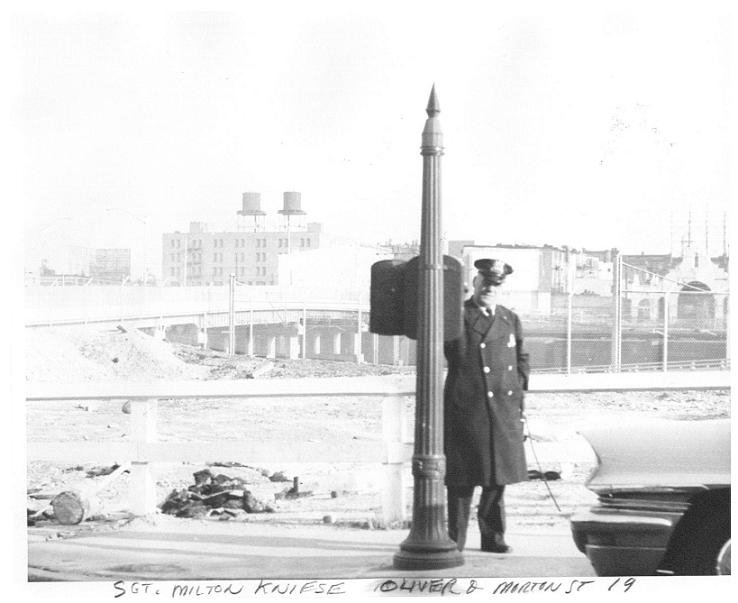

Box #642 was located in the Northwest District

Box #642 was located in the Northwest District

at the corner of Park Heights and Belvidere Ave

The number to call the box was 396-2174

This call box number, #642, was confirmed using a recently

discovered lookout sheets dated 1968 and 1969

these sheets also show the box and phone

inside were paired together on the street back in the late 1960s.

Known Call Box Numbers

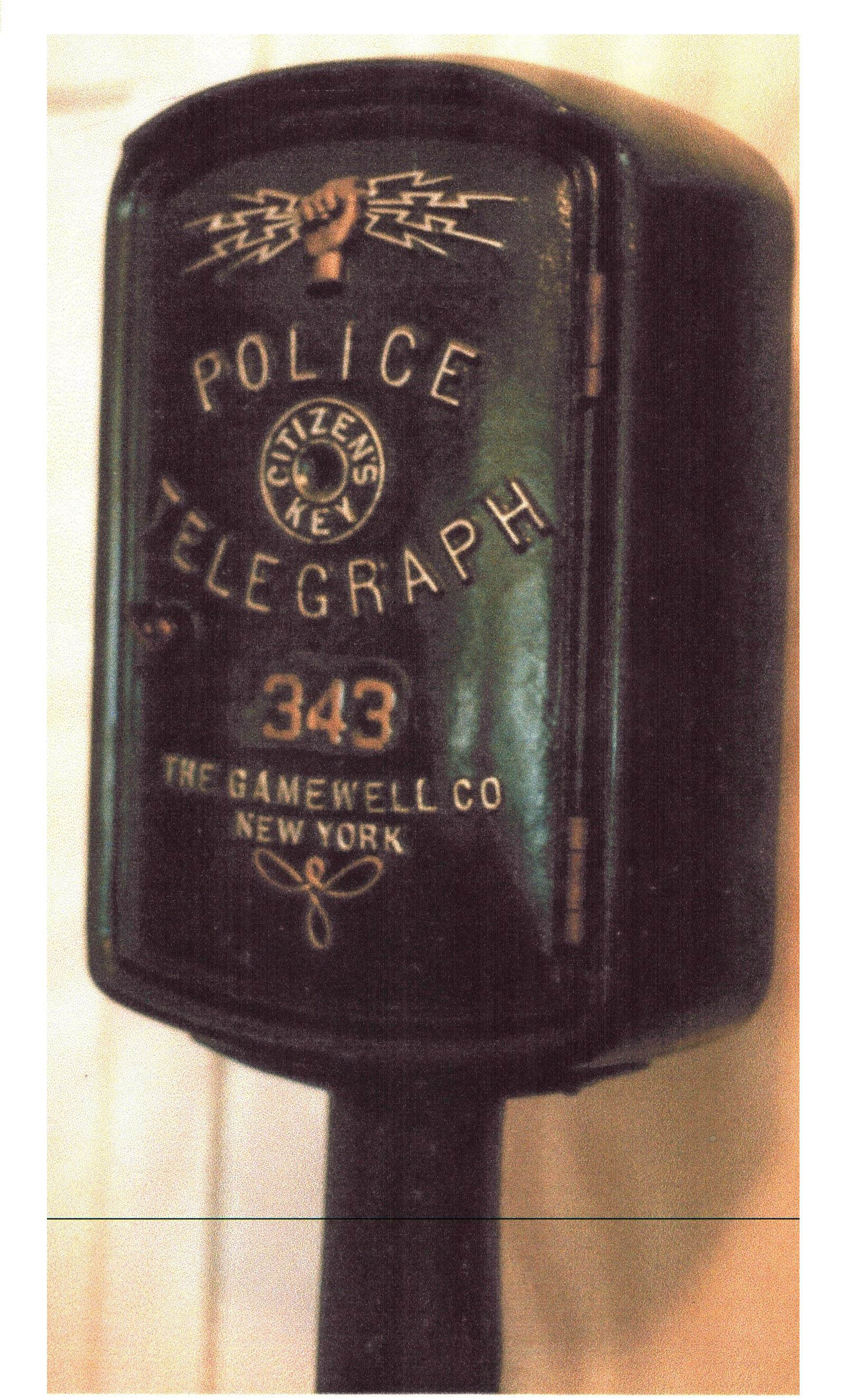

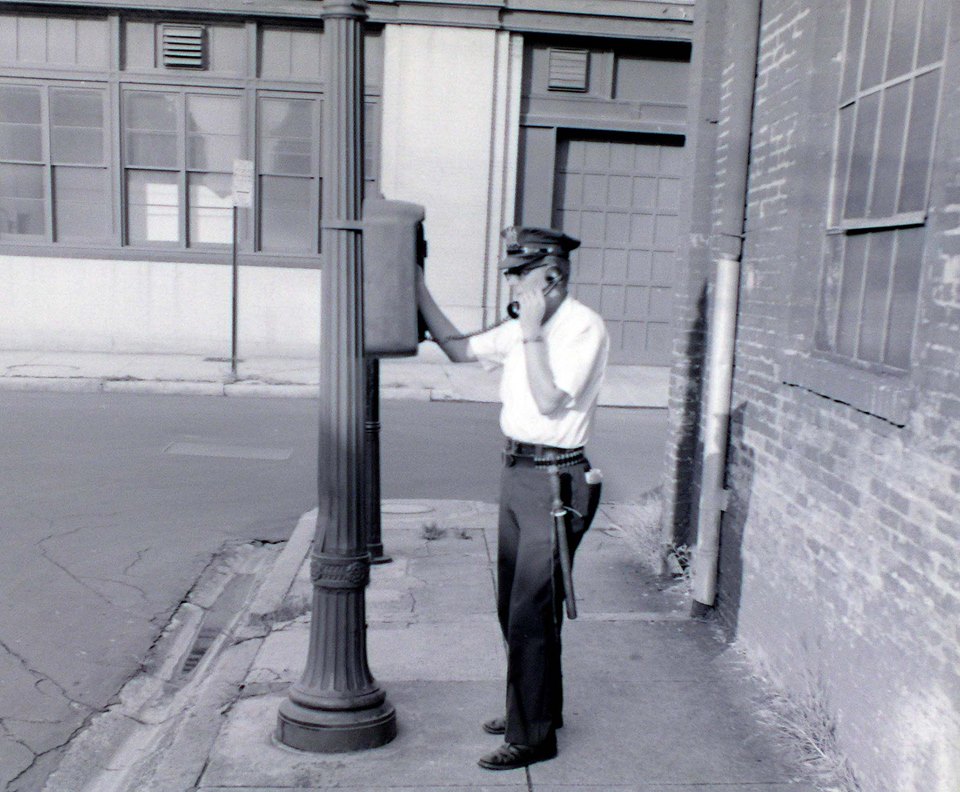

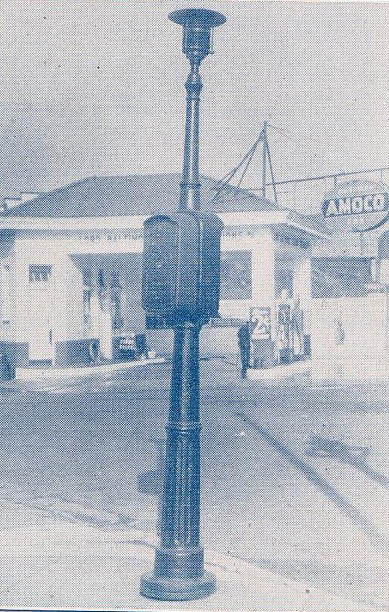

The Call Box

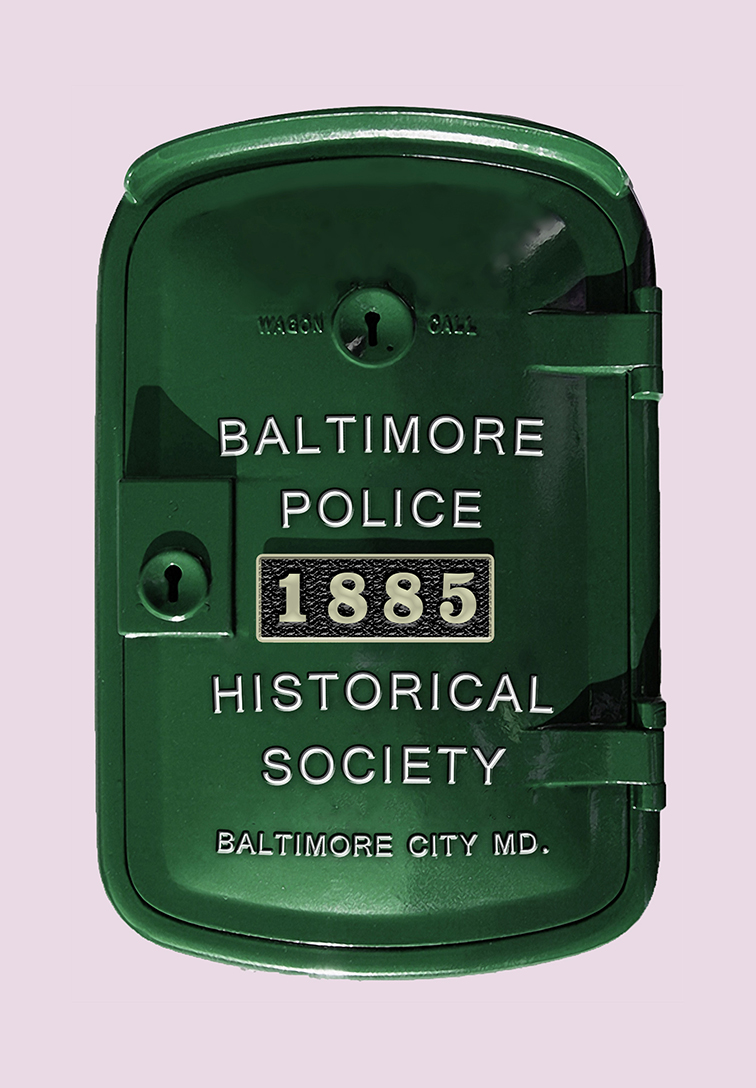

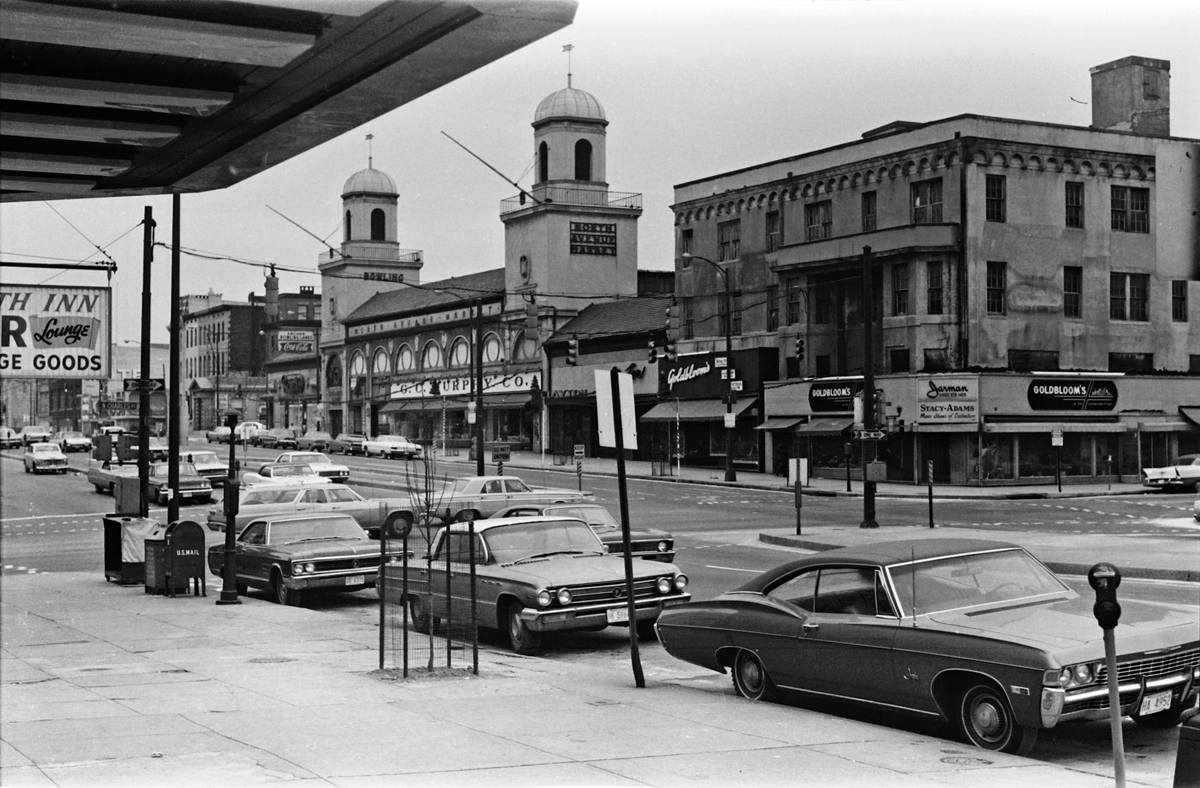

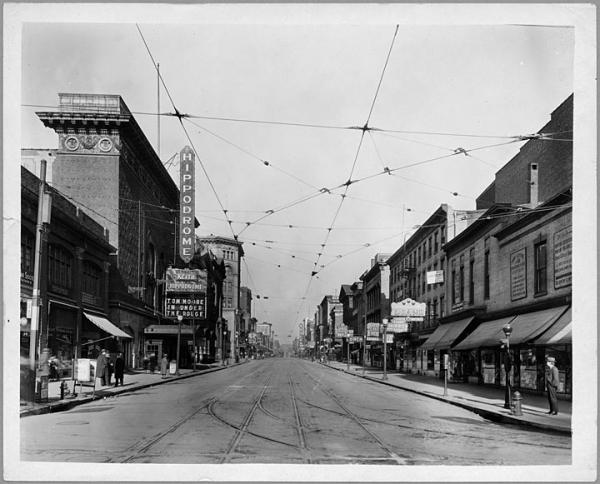

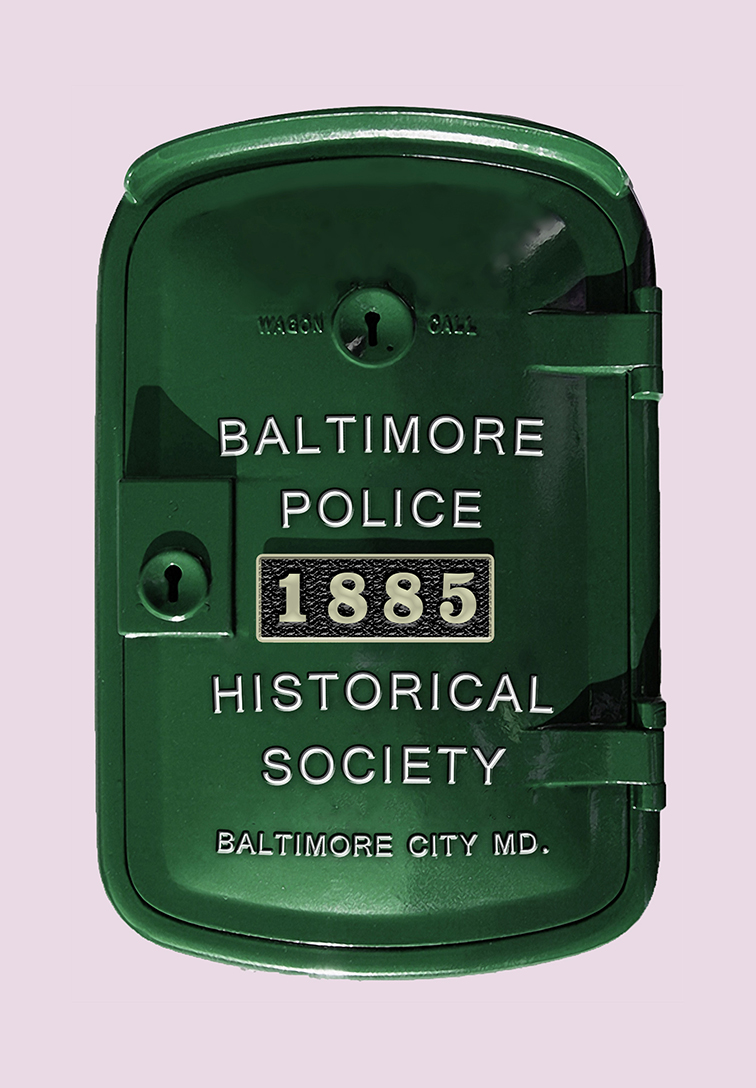

Baltimore got its first call box in 1885. In Baltimore, it is hard to talk about the call box without also talking about the patrol wagon. They are obviously two very different law enforcement tools, but when it comes to Baltimore Police history, they will forever be linked by a Deputy Marshal and a date. Baltimore's first call box came to Baltimore in 1885, and as already mentioned, it was part of a package deal dreamt up by Deputy Marshal Jacob Frey that was made up of both the call box and the police patrol wagon. The date that these things went into service, according to Sun Paper accounts, was 18 October 1885, and it is believed to have made Baltimore only the second city in the country behind Chicago to use patrol wagons.

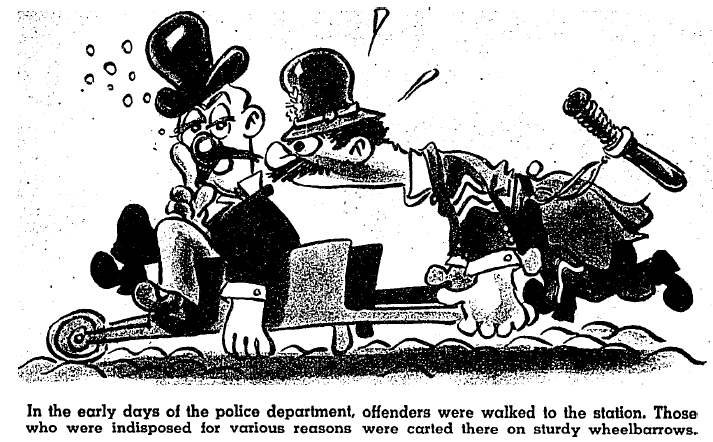

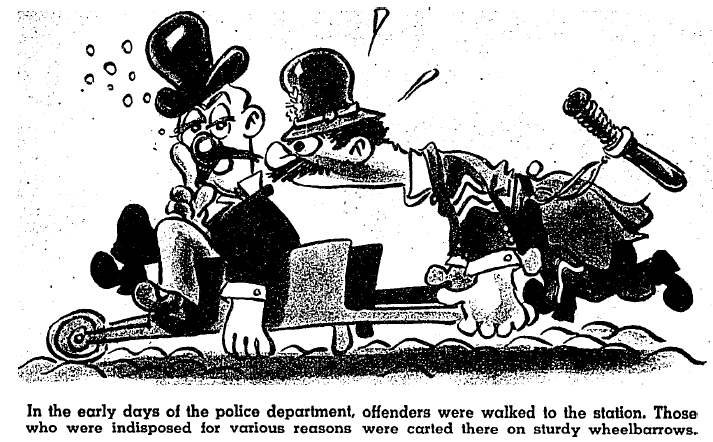

Newspapers recount a story of its all starting while sitting in the gymnasium of Central's Police Station reading an illustrated magazine (most likely Harper's Weekly or Illustrated Police News) when the Deputy Marshal first saw facts on the Police Patrol Wagon being used. Before the use of patrol wagons, when arrested, prisoners were walked back to the officer's station house. In fact, there are many accounts written of officers having to carry drunk, injured, or otherwise incapacitated prisoners back to the station. In some of the cases involving impaired prisoners, they tell of patrolmen commandeering small manual wagons or wheelbarrows to transport their arrestees.

Deputy Marshal Frey took the idea for these tools before the (BOC) Board of Commissioners; they were mildly interested but left it at that. Frey didn't give up on ideas that he believed in, and he saw something special in both the Wagon and the Call Box. For that reason, he gathered more information on these tools, and a few weeks later, he again called the board’s attention to the matter. They had forgotten about it the first time he brought it up, but he promised to look into it and give it serious consideration.

Horse-drawn Police Wagon's and a Police Telegraph Box system were the future of policing in Frey's eyes, and after the BOC failed to act, Frey would take matters into its own hands. He sent members of the department to Chicago to see how the "New Fanged" Patrol Wagons would fit in our agency. An old record states that the team he sent "was charmed." While there, they also looked into Chicago’s new "Police Telegraph System" (the Call Box), and likewise, they found it to be everything the Deputy Marshal had touted it would be. For more information, please take a look at the Patrol Wagon page and the Recall Light page, both on this website, at the following links: Click on either Patrol Wagon or Recall Light to visit either of these pages and look for other links found within these two pages.

The results of Baltimore's trip were that both of these tools were in Baltimore by the fall of 1885. According to Baltimore's Sun Paper reports, Chicago was the first to use the police wagon, and Baltimore quickly became the second. They were first put into use in the Central District on 18 October 1885. As for the call box system, just as they did with the Patrol Wagon, it too was first used in Central District and also came in the fall of 1885. Baltimore would use the call box for just over 100 years, from 1885 until 1986, when a 1-800 number was established for police to contact their district or KGA when radio use was deemed inappropriate. All boxes were eventually removed from service by 1988.

Note: The call boxes and wagons both came to Baltimore at the same time, in October of 1885, and were tested and put into use on a different day. For the call box, it was the 18th of October, and for the patrol wagons, the official date was the 25th of October. I know this is the Call Box page, but a real quick and somewhat humorous note about the wagon is that prior to the patrol wagon or paddy wagon, when an officer made an arrest of a subject who was unwilling to comply, intoxicated or otherwise unconscious and too big to carry back to the station, officers were known to have commandeered help, and most often that help came in the form of a wheelbarrow

Let's take a look at information on that first Baltimore Call Box

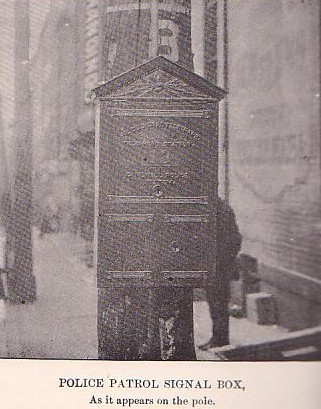

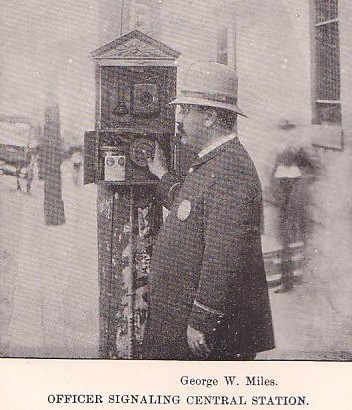

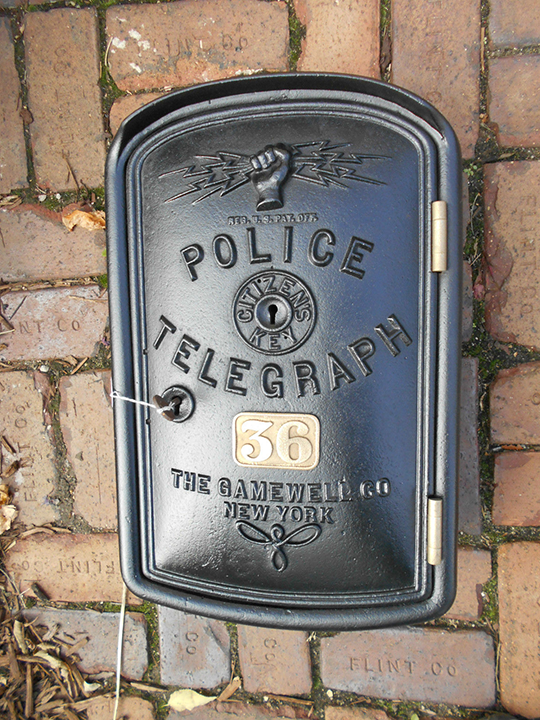

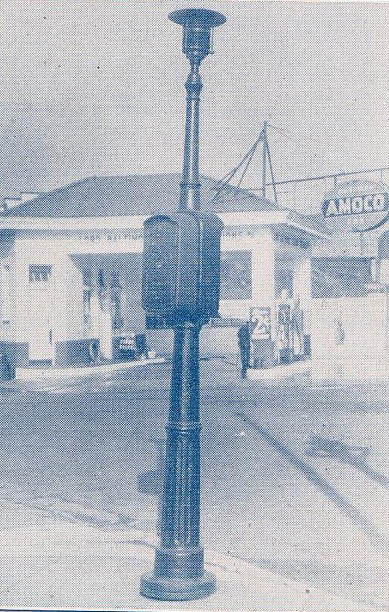

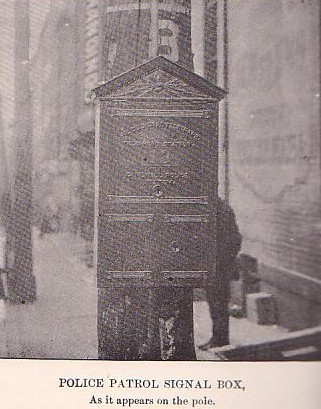

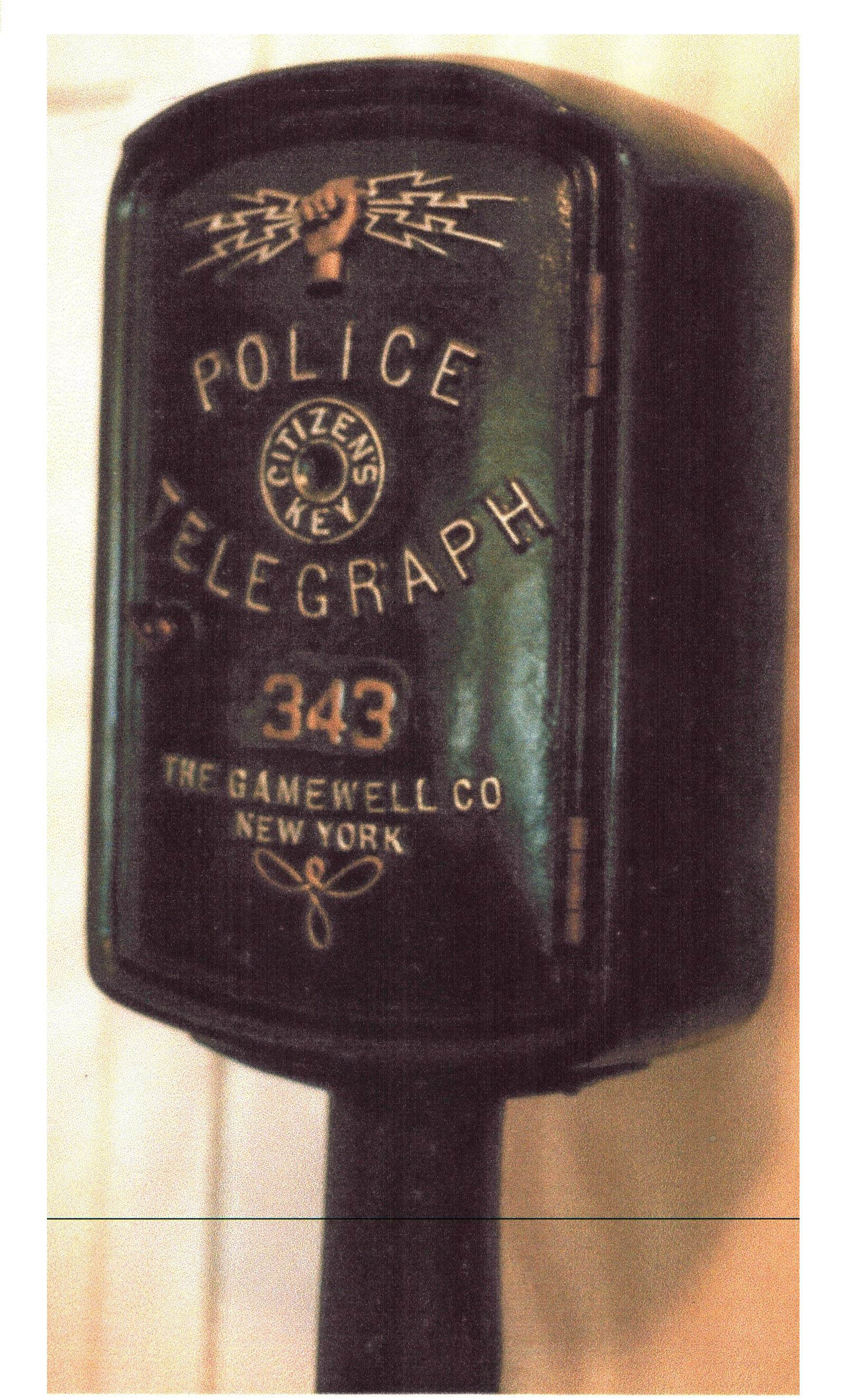

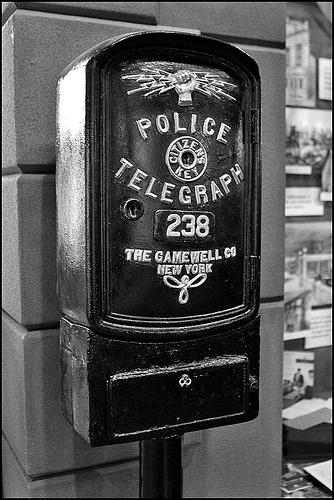

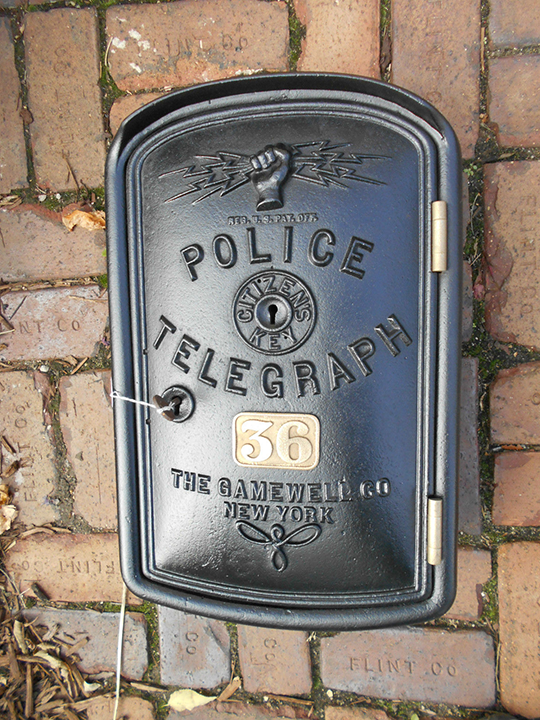

As previously stated, it came on 18 October 1885, the same month and year the Patrol Wagons were brought to Baltimore and put to use. The Baltimore Police Department started using the Police Telegraph Box (Call Box). The pilot program was launched in the Central District with 58 boxes. The system of call boxes would quickly spread to be used in all of the city's police districts and on all bailiwicks. The first call box ever put to use via a test call came from the district (station house) to a patrolman at the call box and then back to the district (station house) from the patrolman to complete the test. The call box used for this test was then Box #63, which at the time was located on the corner of Franklin and Charles Streets in, as previously stated, the Central District, then called the "Middle" District. Our boxes at that time were described as having been attached to a telegraph pole approximately 4 feet from the ground. It was made in two sections at the time; the phone section was in a top compartment, with the lower compartment that housed a "Dial" system in which an officer could point a pin of a dial on whatever he wanted to contact or request; from Back-up, to a Wagon, to an Ambo.

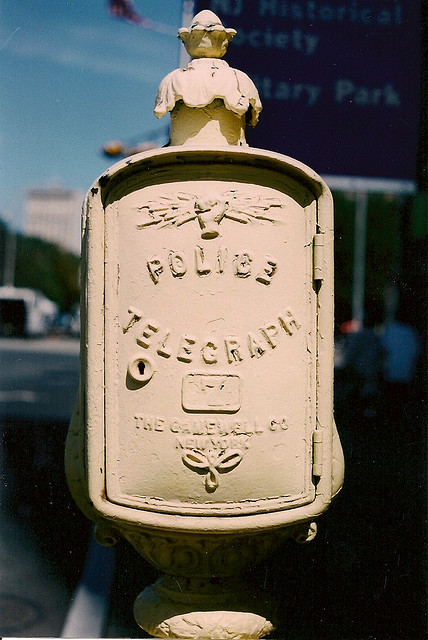

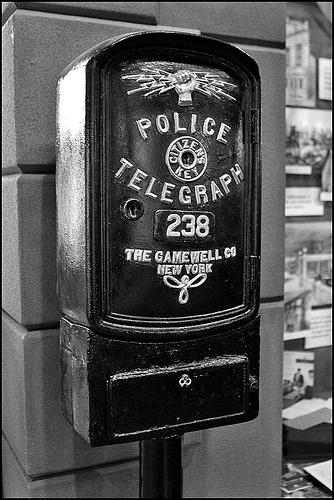

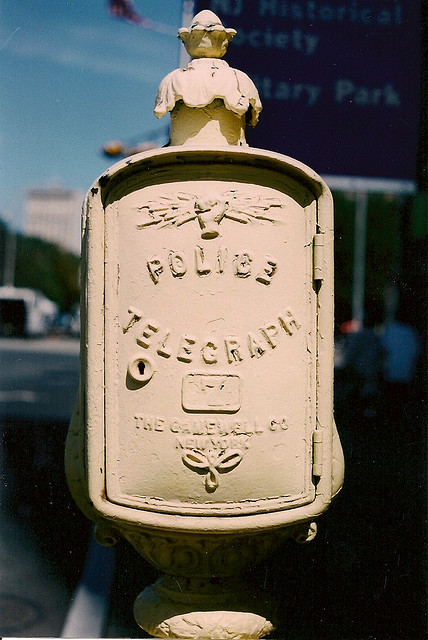

A piece of information not previously known was that the color of the first 58 Call Boxes was "Red." Unlike the single door Gamewell Boxes that have come to be known by collectors as, "The Baltimore Box"; the first Baltimore Boxes, also made by Gamewell, had three doors (one up top and a split two-door down the bottom) and they were not the well know (dumpster) Green we see on reconditioned boxes found in collections, or even in our police Museum. We have two boxes here in our personal collection and extra memorabilia being held here to be swapped in and out of the Baltimore Museum, one of our two boxes is all original with the original pole attached and the original rotary phone inside. It is painted that green the city used on everything the number on the box is 642 which is a number not found on any of the lists until recent when it popped up on a Lookout sheet from 5 June 1969 where it not only lists the box number 642, but the number to the rotary phone inside the box [396-2174] has also come back as listed in the Northwest District on the corner of Park Heights and Belvidere Ave. We have gathered lists on top of lists of call boxes numbers, phone numbers, and call box locations. Our other box also has a box number that was not on the lists, but it has a rotary phone inside of it too, and as soon as we get a chance, we'll will grab the number from that phone and match it up to a district and corner. We have that list on this page and will add to it as more information come to us.

An 1894 advertisement for the "Glasgow Style Police Signal Box System", sold by the National Telephone Company. The first police telephone was installed in Albany, New York in 1877, one year after Alexander Graham Bell invented the device. Call boxes for use by both police and members of the public were first installed in Washington, DC in 1883; Chicago and Detroit installed police call boxes in 1884, and in 1885 Boston followed suit. These were direct line telephones placed on a post which could often be accessed by a key or breaking a glass panel. In Chicago, the telephones were restricted to police use, but the boxes also contained a dial mechanism which members of the public could use to signal different types of alarms: there were eleven signals, including "Police Wagon Required", "Thieves", "Forgers", "Murder", "Accident", "Fire" and "Drunkard".

William Bertazon

Had dinner at Dalesco's in Little Italy

Found the BPD call box #539.

The owner Paul Oliver said it was given to him

by former Police Commissioner Bishop Robinson

Our lists indicate this box came from the corner of

Aisquith and Preston Sts. and would have had a rotary phone

inside with the number - 396-2219 assigned to it

The first public police telephones in Britain were introduced in Glasgow in 1891. These tall, cast-iron boxes were painted red and had large gas lanterns fixed to the roof, as well as a mechanism which enabled the central police station to light the lanterns as signals to police officers in the vicinity to call the station for instructions. These call boxes were not as much like the boxes used here in the US, these were more like what we see in the Dr. Who show. While we have no photographs and are still researching and digging up information, there are stories of us having boxes similar to these in Baltimore over the years, we will continue our research and update this page when we have more information on the subject. For now, all we have what was used and when it was used in other countries.

Rectangular, wooden police boxes were introduced in Sunderland in 1923, and Newcastle in 1925. The Metropolitan Police (Met) introduced police boxes throughout London between 1928 and 1937, and the design that later became the most well-known was created for the Met by Gilbert MacKenzie Trench in 1929. Although some sources (e.g.) assert that the earliest boxes were made of wood, the original MacKenzie Trench blueprints indicate that the material for the shell of the box is "concrete" with only the door being made of wood (specifically, "teak"). Officers complained that the concrete boxes were extremely cold. For use by the officers, the interiors of the boxes normally contained a stool, a table, brushes and dusters, a fire extinguisher, and a small electric heater. Like the 19th century Glaswegian boxes, the London police boxes contained a light at the top of each box, which would flash as a signal to police officers indicating that they should contact the station; the lights were, by this time, electrically powered.

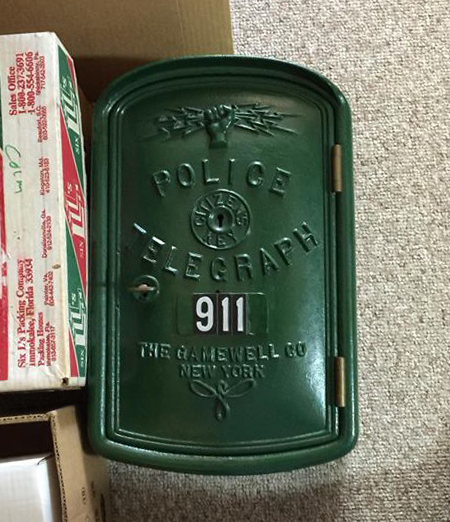

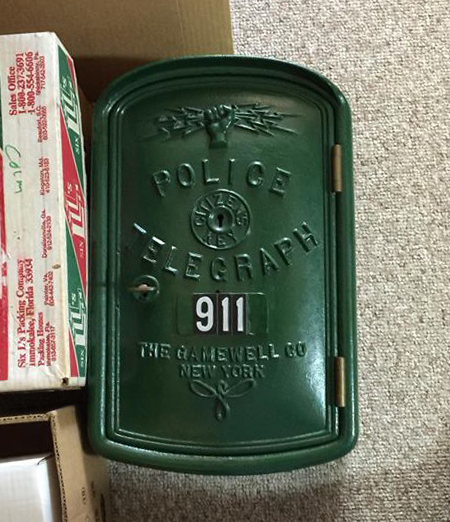

Gamewell Box

Baltimore style

This was purchased from Retired Sergeant Edward Mattson, it had this makeshift Box number of 911 affixed to the plate on the front, but inside attached to the back of the box was a 3/4 inch wooden board apparently used to display award or some other shadow box type display. When we removed the board, we found a few ribbons, a Baltimore Police Department K9 dog tag, and the original Call Box plate numbered of 457. There was a rotary phone inside that had the numbers 301-296-5945, We are assuming it was meant to be 301-396-5945 as our numbers mainly started with 396. We have to search the directories to track this one, but we have it, and will eventually trace it down. It would appear whoever made the 911 plate for this box, was smart enough or cautious enough to have wanted to preserve the boxes actual plate by having stored it inside the box under a false bottom board that was installed to make a shadow box from the call box. We will add a new pic with the corrected numbers when time allows

This box is in what is known as a "Harp" and could be Washington DC

Telephone and Telegraph Division

With traffic signals and supervised by John A. Martin, the superintendent

Progress as told here by Superintendent Martin

Every story must have a beginning, so permit me to go back to January 1918, when I first obtained my position as a lineman with the Baltimore Police Department. At that time there was a Lieut. and a sergeant acting as a superintendent and assistant superintendent of the telephone and signal division, five lineman, one truck and two touring cars used for construction and maintenance.

The equipment to be maintained was 265 Call boxes, eight telephone switchboard, 800 Bluestone gravity batteries, 15 bank alarms, for pawnbroker alarms, eight station houses and approximately 181,665 feet of underground telephone cable. All of this equipment to the best of my knowledge had been in service 25 to 30 years prior to 1918 and was still operating fairly well at this time with the exception of the timestamps and registers which were of the Inky type and at times would be impossible to distinguish one call box number from another as the ink would smear and spread over the recording tape.

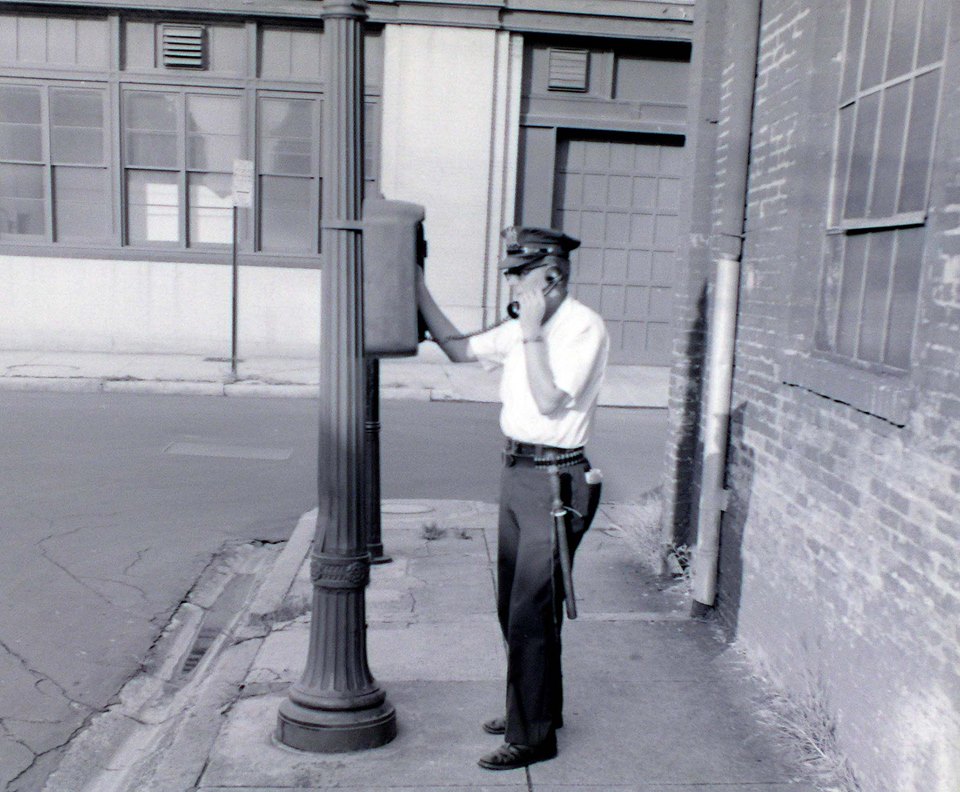

Our police telephone switchboard’s work of what was known then as the target type and operated as follows; when a patrolman wished to make a telephone call he would pull down the lever marked telephone and lift off the receiver. This would release a target on the telephone switchboard which was numbered one, two, three, etc. corresponding to which every circuit he was calling in on. The target was about the size of a silver dollar and when released it would show that the patrolman wished to talk over the circuit. This method of signaling was not very satisfactory, especially when the patrolman had a prisoner at the box, as often times the target which fell by gravity just would not fall. Therefore there would be no indication at the telephone switchboard that the patrolman needed assistance. The only other method he could use would be to pull the lever on the wagon call, but this signal was not audible and would only register on the tape as a wagon call. This often caused considerable delay in dispatching the wagon or assistance to the patrolman.

At that time there was no means of notifying the officer in the district of an emergency or that he was wanted to communicate with his headquarters.

(I mentioned the above equipment and operation of it to show the improvements that were made by the department later on.)

Early in the year of 1921, we installed a signal light on the control box located on the southeast corner of Baltimore and Charles Street. The signal was made up of an electric light bulb, a wash basin to shade the bulb and a Marine lens.

The mechanism for the operation of this light was located in the old central police station house on Saratoga Street near Charles Street it consists of an alarm clock for the flashing apparatus.

This method of notifying the officer that he was wanted proved very successful and at the present time, we have 269 recall lights in operation throughout the city, on a much more improved pattern than the first one. The present recall system consists of one commercial sign flasher in each district station house, which carries 110 V to each recall light located on Call boxes and is operated with a steady or flashing light by the telephone operator in each district. The above method applies to all districts.

Officer John Heiderman and Detective Kenny Driscoll

2016

The way this worked was as follows - If it were me, and I saw the light on, I would have gone to the Call Box, and answered like this: “ This is Officer Driscoll, on the light.” If I were simply making your required hourly call, I would have said: “This is Officer Driscoll on 525, or whatever box I was using.” The operator then knew exactly where “we” were.

In 1921 it was necessary for the police call box system to be extended due to the Annexation. This required the installation of 135,000 feet of overhead telephone wire additional police Call boxes. It was also necessary to increase our personnel from 5 linemen to 9 linemen and one additional chauffeur.

In 1927 I was appointed to fill the position of lineman Foreman of the telephone and signal division under the supervision of the previously mentioned a Lieut. and Sgt. who was now elevated to the rank of Capt. and Lieut.

In March 1934 the practice of assigning members of the force to the telephone and signal division was abandoned after the death of the Capt. and Lieut.

As a result of this action, I was appointed as superintendent of the lineman, telephone and signal division with Mr. George F. Abrecht one of our lineman appointed lineman Foreman.

We then began the task of remodeling are patrol boxes and telephone switchboard. All this work was done in our own workshop and by her own mechanics. With these improvements when the officers wished to call the district, he left the combination handset from the hawk; this flash is a green light on the switchboard in the station house immediately notifying the operator that an officer is on the line and ready to talk.

The register and time stamps were now of the punch type. When a report call is made the tape will be perforated with the box number and report call, also the date and time the call was made. The officers in all districts can also be notified by our flashing and recall system to call their station houses.

The 800 Bluestone gravity batteries have been replaced with the modern storage batteries and rectifiers.

So much for a brief outline of the telephone and signal system.

We also have the traffic control system included in our telephone and signal division. As I feel I have been one of the pioneers in the automatic traffic controlling apparatus I would like to go back to the year of 1919 to 1921 beginning with the hand-operated semaphores. There were approximately eight hand-operated semaphores in service at the following intersections North Avenue and Charles St., North Avenue and Mount Royal Avenue, light and Pratt St., St. Paul Street and Fayette St., Howard and Lexington streets, St. Paul and Mt. Royal Ave., Calvert and Fayette St., Lombard and Howard Street

Beginning in the year of 1921 this number was slowly increased and quite a bit of experimenting was done with different types. The first type was a piece of pipe with a concrete base and the word stop and go on it. The officer operated this with a hand lever.

Next came the semaphore on rollers, the officer standing on a wooden platform with metal shielding around him about the high, this was used to keep the officer from being splashed with mud. This was also operated by a hand lever.

Following this several towers were built 12 feet high. These towers were located on stilts 3 feet from the surface of the street. This was done so as the officers could look over traffic for several blocks in all directions. These towers had a revolving cylinder in the top with the words stop and go and were operated by an endless chain for revolving the cylinder and were supposed to be the last word in traffic control. These towers were placed at Calvert and Fayette streets, St. Paul and Fayette Street, and at light and Pratt Street the towers operated very well during daylight hours, but they could not be seen at night. So the idea was conceived to electrify them, which was done in the following manner. The words stop and go and for elec-cylinder was made transparent with trick light bulbs placed in the center of the cylinder, also an amber light was placed on the extreme top of the tower.

The operation was as follows: when the officer wanted to make a change in traffic he would push a button located on the inside of the tower three times, which would flash the amber light three times warning the traffic that there would be a change, then turn the cylinder to the necessary stop and go. The electrification of these towers was about the beginning of electrically operating traffic signals in Baltimore.

In the month of March 1922, a two-compartment signal was designed by Baltimore engineer. The signal consisted of eight lenses and two electric light bulbs. When the top compartment bald was illuminated the signal was so green, North and South; red East and West, when the bottom compartment was illuminated the top ball but when out, the signal sewing green East and West; and red North and South. This type of signal was installed one trial at Howard and Lexington streets, temporary current being furnished by department store on the northeast corner. The signal was suspended on a span of wire of the United Railway Company. Wires were then run from the signal to the footway on the northeast corner, where an officer operated signal with push buttons from his point. This light was put in operation about noontime of the day that it was installed, and operated very satisfactorily. However the next morning when the officer went up to operate the signal, he found that there was no signal there and on investigation, it was found that during the night a load of hay southbound on Howard Street became tangled up in the signal, tearing it from its moorings and it was not discovered until the farmer was unloading his hay.

In April 1922, a traffic tower was constructed at North Avenue and Charles Street [which still stands], high enough so an officer standing in this tower would have a clear view of North Avenue. From Howard Street to Guilford Avenue and on Charles Street from Lanvale to 23rd St. the idea at the time was to operate traffic as follows.

When the signal would show red on North Avenue all vehicle traffic on North Avenue between Howard Street and Guilford Avenue was supposed to come to a stop, north and southbound traffic between Howard Street and Guilford Avenue was permitted to move. This did not work very satisfactorily due to the type of signal used at this time, the lens being nothing more than colored glass without reflectors and was hard to distinguish. So the idea of controlling traffic from one signal, on North Avenue from Howard to Guilford Avenue was not put into effect and it was decided to control the intersection of Charles Street and North Avenue and only.

In June 1922 it was decided to install two traffic signals, one to be located in St. Paul and Fayette Street, the other at St. Paul Street and Lexington, which was completed in July, 1922, and was the same type signal that had been previously tried out at Howard Street and Lexington Street but instead of being suspended they were on a pedestal. These signals were operated manually by pushing buttons. The signals were operated until 1923, during this time more modern traffic signals were being developed by several manufacturers.

We were induced to try out to more modern type signals which we did. The signals were called the Milliken talking lamps and consisted of four red lenses and four green lenses being set in a box type metal housing that would rotate a half turn at each force of the button. The operation was as follows, the signal, for example, would be green for North and South traffic, the officer would push the button which would start a motor operating which in turn, would rotate the box type signal half way around or vice versa, also ringing a bell and blowing a horn which could be heard for several blocks. This became very objectionable to the office workers of this locality and had to be discontinued.

During this period of time from the last insulation until January 1924, there were no traffic signals installed. In January 1924, modern traffic signals which now had been developed were installed on North Avenue from Guilford Avenue to Howard Street, also Charles Street and 20th St. The colored glass signal was removed from the tower at North Avenue and Charles Street and more modern signals installed which are still standing.

All signals on North Avenue. From Guilford Avenue to Howard Street including Charles and 20th St. were interconnected and operated both automatic and manually [this being the first automatic operated traffic signal in Baltimore], from the tower at North Avenue and Charles Street. The operation was as follows: movement number one, signals all read on North Avenue from Guilford Avenue to Howard Street; movement number two signals all green on North Avenue from Guilford Avenue to Howard Street. This system stayed in effect until October 1928. Several isolated intersections were signalized in the year 1924, including North Avenue and Mount Royal and Linden Avenue and Biddle Street.

March 5, 1925, a tower was erected at Mount Royal Avenue in St. Paul Street the same as North Avenue and Charles Street. Traffic signals were placed on St. Paul Street from Mount Royal Ave. to Monument Street to mast arm type signals were installed at each intersection. The signals operated both automatic and manual as follows: the signals were timed in pairs, for example, St. Paul and Mt. Royal and St. Paul and Preston would be green, St. Paul Biddle St. Paul and Chase Street would be read this operation continued until December 1 of 1928.

February 22, 1928, the first vehicle actuated control was tried out in Baltimore. (To the best of my knowledge this was the first vehicle actuated signal insulation in the world.)

This was an automatic control were a brake attachment and two finals placed on polls on the right-hand side of the cross street, ordinary telephone transmitters being installed inside the finals. These transmitters being connected to the sound relay, which when disturbed by noise, for example, the blowing of warns, tooting of whistles, or the sound of voices would actuate the sound relay, releasing the break on the automatic control permitting the motor to run. This would change the signal which had been green on the main street to Amber, then to read, permitting the side street traffic to move out on the green.

This control would always restore itself back to the main street green, then the break would set and the signal would remain green on the main street until disturbed again by sound. Several of this type were installed, one being at Charles Street and Coldspring Lane, another at Charles and Belvedere Avenue

This type of actuation was not found very satisfying for the following reason. Residents of the locality where these type signals were installed, complained of the continuous blowing of warns, whistles of locomotion locomotives on nearby railroad would actuate the control. Considerable trouble was caused by boys throwing stones into the finals. To overcome these objections it was necessary to install a hollow metal box in the bed of the cross street with the same type transmitter, installed in the metal box as had previously been used in the finals. The wheels of the vehicle passing over the hollow metal box would transmit sound to the transmitter the same as was done previously by the blowing of horns or other noises.

This type works very satisfactorily and we still have it at present time in several locations throughout the city.

The first flexible progressive traffic system installed in Baltimore was put into service on Baltimore Street from gay to Howard Street, from Howard Street to Baltimore to Franklin Street in the month of July 1928. This insulation consisted of a 4 2 way signals at each intersection, automatic and manual control at each intersection being controlled by a master timer located in the basement of the police headquarters building, this master time being connected by a lead to covered cable to all intersections.

This system works very satisfactorily and in the year of 1929, the following intersections were put in service. One Fayette Street from gay to You Tall St., Lexington Street from gay to Howard St., Redwood Street from Calvert to Howard St., Franklin Street from Park Avenue to You Tall St., Fallsway from Fayette to Helen St., Charles and Saratoga Street and Lombard and Liberty Street. This entire group of signals being operated from the same master timer as Baltimore Street. This system is still operating at present time March 1945

In October 1928, the same type of flexible progressive system was installed on North Avenue from Guilford Avenue to Howard Street, replacing the system previously mentioned on North Avenue from Guilford Avenue to Howard Street

December 21, 1929, The flexible progressive system was put in service at the following locations: on St. Paul Street from center to Mount Royal Ave., on Cathedral Street from Mulberry to Mount Royal Ave., on Charles Street from Franklin Street to eager Street, on Mount Royal Ave. from Calvert to Cathedral Street and on Fallsway from eager the Preston Street.

This system was replaced by a triple reset progressive system in July 1942. This system favors the movement of southbound traffic in the morning and reverses itself in the afternoon.

This is accomplished automatically by time clocks and has proven very successful. This department maintains the following equipment: 434 intersections controlled by automatic traffic timers; 216 electric pylons; five master traffic controls; approximately 1 million feet of traffic and telephone underground cable; 25,000 feet of overhead telephone wire; eight telephone switchboards; 355 police Call boxes; 269 recall boxes; 600 storage batteries; 13 pawnbroker alarms; 46 bank alarms; and 15 police buildings.

In addition to the maintenance, this department does all of the construction and new insulations of traffic signals and telephone equipment. We do this with the following personnel; chauffeurs Charles J. Brown and Frederick M. Crum it, Lyman John H. Childs, Albert R. Cresswell, L. Graham Doyle, Lewis W. Eckerd, John A. Funk, Stuart M. Gates, Nelson S. Go brick, Clyde leered, Clarence N. G. Louver, Earl J. Myers, John H. Morgan Wick, Lewis W Orem, John M. Show well, foreman Albert G Warfield and myself John H. Martin superintendent of system.

1922 - 17 Sept 1922 - Recall Lights are put to use for the first time in the country. Police of the Central district began operating the new police recall system. Every uniformed man from the inspector to patrolman was enthusiastic over the results. The first week of the "Magic Blinkers" has created a demand from other districts and other jurisdictions that the system be installed everywhere immediately.

Courtesy Patty Driscoll

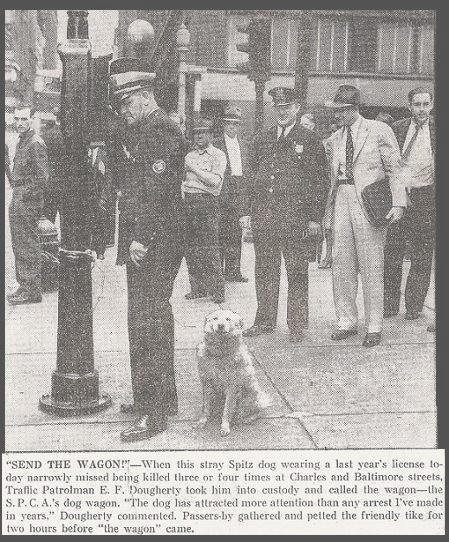

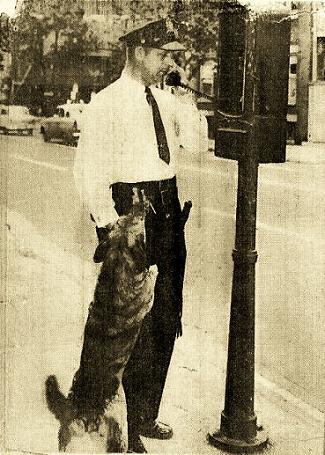

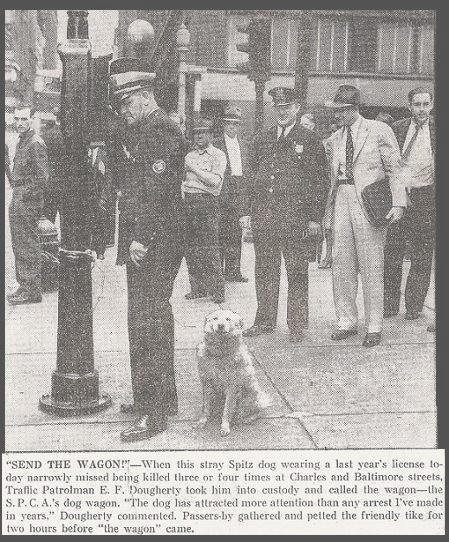

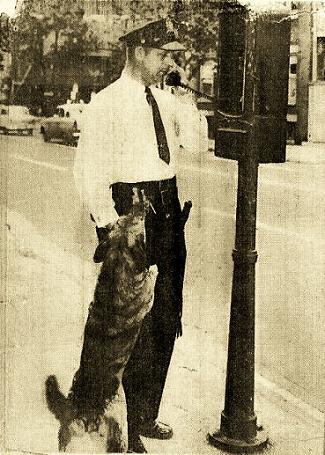

Wagon Box

Courtesy Patty Driscoll

Wagon Box

Courtesy Patty Driscoll

Wagon Box

Courtesy Patty Driscoll

Wagon Box

Police Lights Nemesis of Evildoers

Like Centennial’s Their Winking Rays Stand Ready To Issue Calls to Urgent Duty or to Foretell Tragedy

Like a mischievous I, a blue light was winking slyly at the edge of the sidewalk. Winking persistently at anyone who would look at it. At the same time, all over Baltimore hundreds of similar lights were also winking.

The average pedestrian paid no more attention to the flashing light than to ogles of an unattractive girl. A custom as he was to traffic signals, electric signals, street lamps and the hundred and one other lighting devices which modern city life has evolved, he didn’t even notice this one.

But scattered here and there over the city were some thousand men who leaped to respond at the first link they saw with the alacrity of a lover at the call of his most chairs sweetheart. They were members of the Baltimore police force, and they knew these lights might have important things to tell them.

To safeguard the citizens of Baltimore from its members who have wandered off or slipped from the lawful course of life, the city has been divided into eight districts. When something goes amiss in any section it is possible to inform practically every Guardian of the peace of that fact within a few minutes.

Here is how it works; a store is robbed, perhaps in the Northwest section of the city. The thieves escape an automobile. The owner of the store telephones police headquarters. There he is switched to the chief inspector's office, where he excitedly gives such descriptions of the men who robbed him and their car as he can recall. The Sgt. on duty helps him out by asking pertinent questions. Sometimes the person reporting is too upset to talk coherently.

Having obtained what information he can the Sgt., almost before the man is finished talking, is giving the signal on the private wire which puts the eight police districts on the telephone at once. He gives the facts of the robbery just want, and all eight districts throughout the city have the theft on record.

The man on the phone at each station house presses a button immediately. Lies begin to wink all over the city, informing patrolman, motorcycle police and detectives working in the eight districts of the city, to call their district headquarters.

As soon as each man on duty sees a flashing light, he calls the station house in his district and is given an account of the robbery.

Within a few minutes, ordinarily, the news has been flashed all over the entire city by means of these blue lights winking from the top of the police Call boxes and from the rooms of station houses.

There are in the city of Baltimore 1350 patrolmen, 170 sergeants, 25 detective sergeants, 25 detective patrolman, and 25 Lieut. Detectives more than 1500 altogether.

By this simple device of pushing a button, or flashing on a light by lifting a lever, it is possible to get in touch with most of this force scattered over the city and in incredibly short time.

It has been quite a step from the days when the police used to communicate with one another by striking on the sidewalk with their Espantoon.

It is such an easy thing to push a Bell or release a whole and flash on a light at the telephone exchange. Yet it strains the imagination to reflect upon the far-reaching and complicated process such simple little actions can start.

The chief inspector's office is a fascinating place. There can be observed the mysterious complex working of the network of wires which are like the nerves of a modern city.

In one corner is a little brass instrument connected only indirectly with the main telephone nervous system. It is used to convey information of a specialized kind, of attempts to gain unlawful possession of private property.

This machine is engaged with approximately 100 banks in the city. When someone holds up one of these institutions and alarm can be sent to police headquarters by any one of the banks who is lucky or sometimes unlucky enough to have his hand on the push button placed in a convenient and hidden place in the bank for just such an emergency.

Automobile stands outside the courthouse waiting for just such calls. The bell has hardly finished placing off the signal which tells what bank is in trouble before detectives are speeding to the spot.

But most of the process used to trip up the criminally inclined are in place before they have completed the crime in progress, allowing this system and the telephone to help aid in their capture.

The telephone wire in the chief inspector's office is kept hot all day, according to the Sgt. there, with signals of distress coming in from all over the city. Some strains, a few tragic, and many inconsequential things appear on a daily record sheet, where requests for a patrolman are recorded.

A woman reports a man looking at her window.

A dice game is seen and police assistance demanded to break it up.

A fight is going on in a saloon on such and such a street.

Two children were heard to cry out, but when the person telephoning got there they were not to be found.

A noisy party is extending its residents to far into the night.

An automobile has been parked on the wrong side of the street for more than an hour, according to the woman who has been watching it from her front window.

Some schoolboys playing ball on a nearby lot are too boisterous us about it.

Cries were heard coming from a neighboring house.

A light is seen burning in an unoccupied building.

Smokey smelled at a certain Street intersection.

A woman is lying under a streetcar.

A man drops dead on the corner.

A couple has been fixated at a house on Fayette Street.

A drunken man is lying in the gutter near a certain corner.

Among all these, there will appear occasionally some strains bit like this; Mrs. C. Reports that the new fence post around her yard was removed and was meeting ones substituted for them.

Or Mrs. B. Says she is being followed continually, and that a Dictaphone has been installed in her room to listen to what goes on there.

“But we always treat all requests for the service of the patrolman seriously, no matter what the matter of the request,” says the Sgt. “We send a man up who looks at the fence post quite gravely, soothes the fears of the caller and returns to the office to report what is or isn’t quite right.

“Yes, we have quite a few of these curious calls. Some of them come in regularly from certain sources which we have learned about from previous experience. We have a list of these regular customers, of course, so we know how to take them.

“Most of the complaints come by telephone, but there was one recently which was too indignant to be trusted to the wire. The woman came in and person to deliver it. “I want to report a traffic officer,” he said, “He just called me a jaywalker. I don’t know what he meant, but I won’t be called such a name by anyone.” But the face to face complaint or request for patrolman is rare; probably it is well for the chief inspector's office that it is.

The telephone has many advantages other than that of being a time saver.

Police departments all over the United States can get or give information quickly this way and cooperate in catching criminals who have fled from one city to another. There is the cable for still further distances.

A button may be placed in Baltimore or lever released a flashing light and vibrations from that simple little act may cover a good portion of the Western Hemisphere, going on for months, sometimes for years.

The man is a thinking animal, a close wearing animal, a tool using animal, men of letters have said at various times, all vying with one another in defying the human being in the shortest term.

The last of these, a tool using animal, perhaps is best for modern uses. The man is a tool using animal, but in recent years he has learned to work with many of the tools by merely pushing a button.

Policing Baltimore

200+ Years

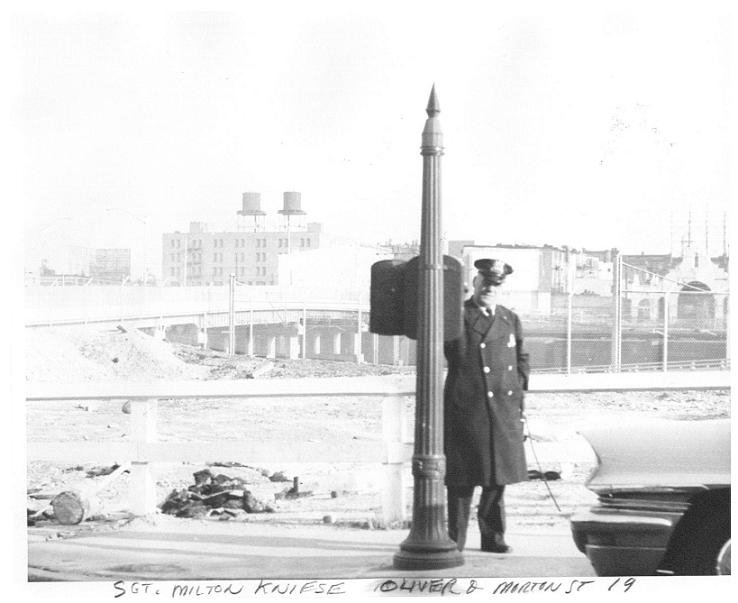

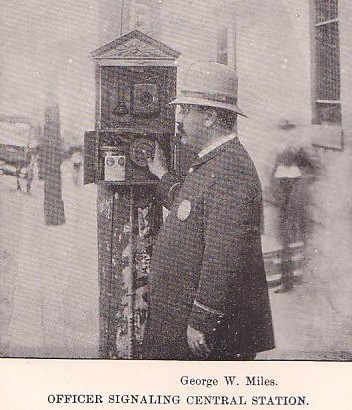

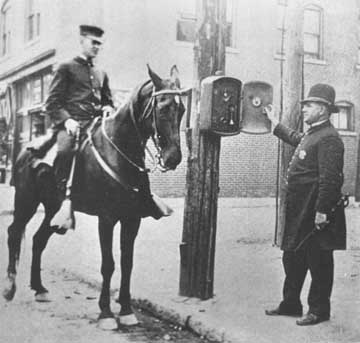

The process of police communications was difficult and time consuming for the men in blue who patrolled the streets of Baltimore up until 1884. It was at this time that word reached Baltimore that the Chicago Police Department was instituting an innovative communication system called the Police Telephone and Alarm Telegraph.

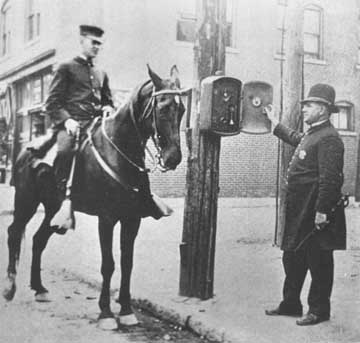

Marshal of Police John T. Gray in company with Mr. James F. Morrison of the Gamewell Fire and Police Alarm Company was dispatched to Chicago to inspect this unique system. They were highly impressed with the network but immediately observed one drawback. The electric stations were placed inside small round houses, which were similar to telephone booths. The disadvantage of such a set-up was obvious to Marshal Gray who pointed out that it would he difficult for an officer to bring a prisoner into the house with him or hold him with one arm outside the door while he operated the instrument.

The Marshal and Mr. Morrison rejected the round house idea and designed a simple metal box which could house the circuit and could be easily mounted on a pole. This unit became known as a "Call box" and has been copied and praised by law enforcement officials as a more convenient and accessible unit than the round house.

The call box system was instituted in the Central District by the Baltimore Police Department on October 26, 1885 when 59 boxes were activated. It was activated in conjunction with the Patrol Wagon System and the combination proved to be so successful that the other three districts, Eastern, Southern and Western soon followed suit with their own call boxes and patrol wagons.

Each call box had both a modified telegraph and telephone inside, The telegraph consisted of a brass plate with five symbols on it and a pointer, When an officer made his hourly call-in or wanted to transmit other messages he would set the pointer to the proper signal and pull the lever. The message would be received by the station house through a ticker tape machine which would punch out the date, time, box number and pointer position.

After the lever was pulled the pointer would return to the wagon call position as a safety precaution. If an officer needed a patrol wagon he merely had to pull the lever. The tape at the station house would show that a wagon was needed at that particular box and one would be immediately dispatched.

Another needle position when transmitted indicated to the station house operator that the officer wanted to talk on the telephone. With the phone he could pass on important information to the station and request help during sudden emergencies.

Calls to the station were easy, but only when such a call in was made could the station contact the officer. This problem was soon overcome when the "recall light" was added to the system.

These lights were placed throughout the city in such a way to be highly visible for great distances, The dispatcher when he wanted lo relay a message to a field unit could engage the light in one of two modes, either a steady burn or flashing light. A steady burn indicated a routine call. A flashing light meant an emergency. This system worked well enough except for one nagging difficulty.

Since call boxes are essentially telephones, they require wires to be run from one terminal to another, to keep the wires secure and reliable they were run in existing underground conduits and attached to each other in a series circuit. The location and circuitry of the Gamewell System was therefore limited to where the underground conduits happened to run. The problem was that when the dispatcher engaged the call light for an officer in a certain Bailiwick all the lights came on at all the other boxes on the same circuit. Kind of like a party-line So, for example, if the officer was needed who worked the area of Pennsylvania Avenue and Lafayette Street the dispatcher at the station would engage the light to call him to the box located at that corner. Unfortunately, all the boxes on Pennsylvania Avenue on the straightaway from Lafayette to Garrison Boulevard were hooked to the same circuit, so, they all came on. If officers along the line happened to respond to the box before the assigned officer they were bluntly told, "We don't want you." It isn't hard to sympathize with those early officers who, perhaps on a cold, rainy night responded many times, lo their call box only to be told that the call wasn't for them.

Sometimes the call box operator at the station house would put the steady burn signal on and an officer would answer the light. When the officer was told the call wasn't for him he would depart only to see the light come on again moments later. Often the officer would assume that since he had just talked to the station the light must he for someone else and went on about his duties. When this happened the station operator might put the light on a flashing mode to make the officer respond back to the call box.

In 1949 the Gamewell System was abandoned in favor of a telephone system that was tied into a centralized location on the 5th floor in the combined Central District/Headquarters Building at Fallsway and Fayette Street. This system utilized telephone company facilities which allowed for greater flexibility and control over the dispatch of calls for service.

One dispatcher was assigned to each patrol area of the city and was seated before a console that was essentially a telephone switchboard. As with the Gamewell System, the dispatchers were responsible for not only dispatching assignments but also receiving citizens' calls for service. Utilizing telephone company facilities allowed each call box to be placed on an individual circuit. This allowed only one officer to be summonsed to his call box rather than all officers responding under the old system. If necessary, the dispatcher could activate as many recall lights as necessary and talk to a number of officers amassed to share similar information to everyone at once as in the case of a description. If all officers were not available at the same time however, the description could he missed by a few. To preclude this possibility a magnetic wire recorder was installed.

The dispatcher could either pre-record the description or record it as he was giving it out. If an officer who did not originally receive the description later called in the dispatcher would merely plug him into the recorder while he went about his business. The recorder allowed the dispatcher to let a unit hear a message while he remained free to converse with another footman.

In 1933 an event occurred in the Baltimore Police Department which would herald a new era in Police Communications. On March 4, 1933, Radio Station WPFH went on the air as the voice of the Baltimore Police Department.

The Call-in used for the various Call Boxes was as Follows

Officer Claude Merritt worked 723 Post located at

Edmonson Avenue and Pulaski Street.

Every hour on his Call Sign he would call in.

as much as 5 minutes early or 15 minutes late.

After 15 Minutes, the Recall Light Lit, and

the Sergeant and Post Car came Looking for him.

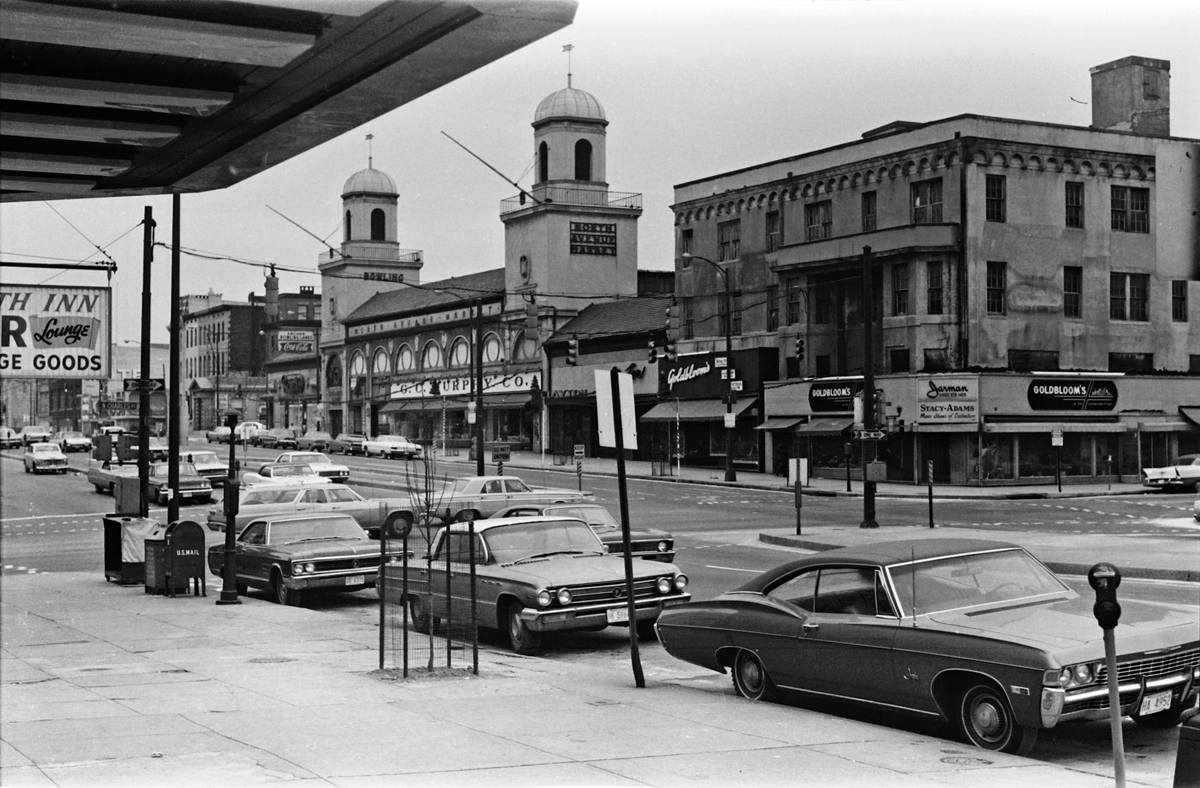

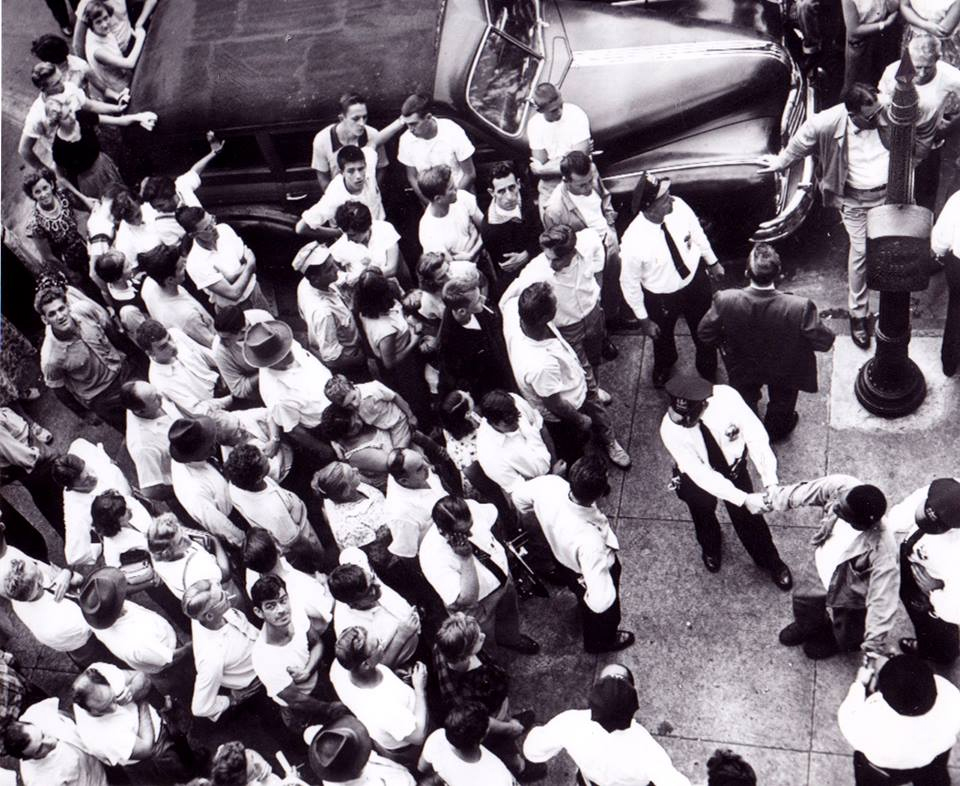

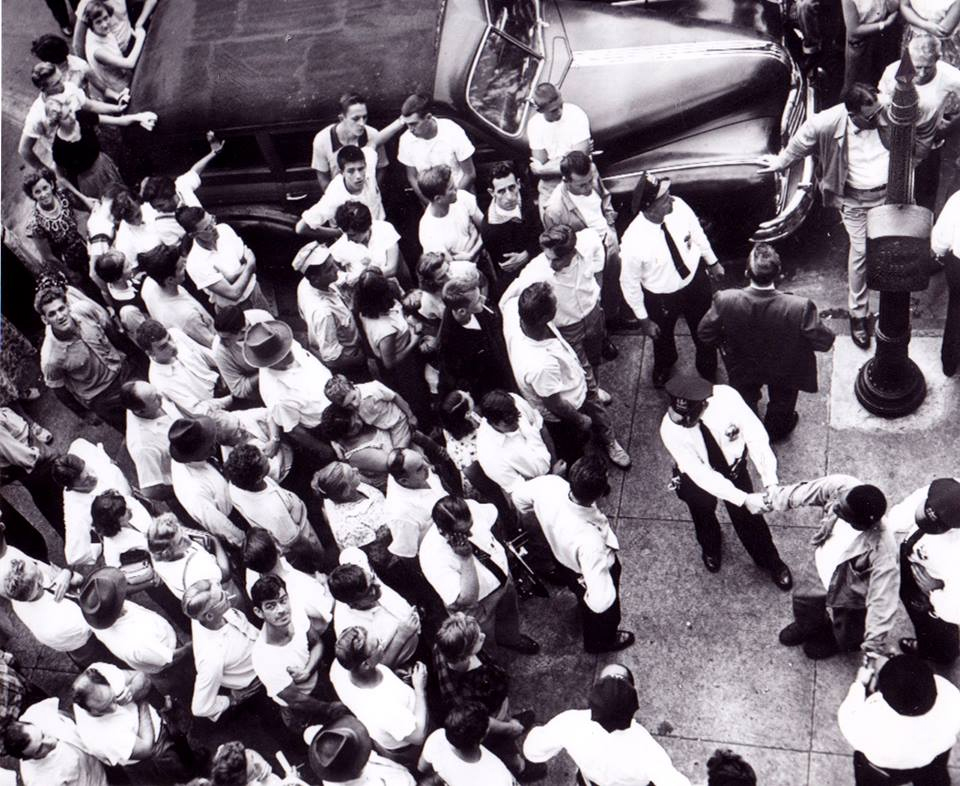

We purchased this photograph for the Call Box and it's Post Cap found on the upper left side corner of this picture. The top of the post where a Recall Light may have once been but has since been replaced with an Ornamental Iron Post Cap. But when we received the picture we couldn't help but notice a resemblance to one of the men in the crowd, and my grandfather. The next time my uncle [Mike] had come to visit, I asked if this was his father, my grandfather ; he not only confirmed it is his father, [Charles Driscoll Sr] but suggested I should have looked at the younger men around him, and a lady holding a baby not far from Pop and our uncles. It turned out in this picture was not just my grandfather, but also my uncles, and a lady holding a baby that could be my grandmother, we are not 100% on my grandmother being in the picture, but the men are defiantly my grandfather, and a few of my uncles.

Special Thanks to John Heiderman, Patrick Youells, Jeff Hewett, Bernie Wehage, Kevin Larmore and Claude Merrirr for providing the info that helped compile this list.

_______________________________________________

If you have a call box and need numbers we had these made - he can do any 3 or 4 number combination.

Our box came from the corner of Park Heights and Belvedere Ave. the phone number inside the box was 396-2174 so the correct box number should be 582

We could have put a badge number, the correct number for whatever box would have been on our old post. Like I used to work Whitelock and Brookfield. If this box didn't have any indication as to where it may have been I could have looked up the closest box to that which... we can find on this page above. I like the correct number, and if that isn't possible going with the true box number for the area I worked would be next best. So again, I worked 136 post, and that would have been the box on the corner of Whitelock and Mason or box #511.

This link is to the guy that made these for us his name is Bob Park... he does fire alarm boxes too. Tell him you heard of him through the Baltimore Police History site

https://www.ebay.com/itm/323386519323?ul_noapp=true

Photoshopped Baltimore Call box

Call Box with Recall Light on top

Recall light hit the streets and our Officers came up with a way to have the kids in the neighborhood get involved. The first kid to let the officer know the light was on would get a penny. Officers rarely missed calls, and build a rapport with the kids, which later grew into receiving tips on other wrongdoers in the area.

POLICE SOON READY WITH NEW ALARMS

"Recall System" Will Be Completed

In Two Districts Early Next Week.

PLANS CITY-WIDE EXTENSION

Gaither hopes to have All Baltimore Covered by Light Signals next Year.

After delays and complications for more than six months the new police "recall system" will be completed early next week in the Central and Western districts, it was announced yesterday by Charles D. Gaither, Commissioner of Police. This system, conceived by the Commissioner, will be established throughout the city by next year, Mr. Gaither said, providing an appropriation permits it.

Having been tested through experiments with the call-box at Baltimore and Charles streets and in outlying sections of the Northern district, the system is regarded as feasible and satisfactory and is expected to aid in the quick capture of criminals. Through the "recall" patrolmen all over the city can be summoned immediately and instructions were given to the entire force at one time.

How System Works

All police call boxes in the Central and Western districts are being equipped with a red light projecting over the top of the box. A cable connects with the series of boxes to the respective districts and with headquarters. When a patrolman is wanted his box is "flashed." And the light blinks until the telephone receiver is removed from the hook. If the entire force is wanted every box flashes simultaneously until answered. Under the present system, there was no means of obtaining communication with patrolmen on the street. The policemen call their respective districts every hour and between the hours of call unless someone is dispatched to call the officer wanted. There are no means of locating him. When the light flashes the officer will know that his district wants him and will answer.

City-Wide System is Good

“The plan is a good one. I think.” commented Mr. Gaither ... “and by next year we hope to have the system installed in all of the eight districts. If all of our appropriations were sufficient this will be done. We were delayed this year when we received the wrong equipment and had trouble obtaining the correct cable. The siren system, as established in New York banks, was commended by the Commissioner. Banks in downtown New York have been equipped with huge horns that are blown in cases of robbery or hold-ups, and attention is immediately attracted to that point. The idea could be adopted here advantageously.”

Gaither suggested.

A MYSTERY POLE LOSES STANDING

AFTER CATCHING PUBLIC EYE, IT FINDS AN UNBLINKING END

Inspector William E. Taylor director of communications for the police department and local highway engineers have written "finis" to the story of Baltimore's mystery pole. The simple green pole, in mid-sidewalk at the northwest corner of the Broadway and Monument street intersection, was taken down at the end of last week. Highway engineers wrote the police several days ago to suggest that it be removed, calling it an "obstruction." CREATES MILD FUROR

The pole, which at one time served as a recall light with a flashing signal to attract policemen to a nearby call box, had become a mystery recently when neither the police nor several city departments would admit having put it there.

It created a mild furor among curious persons who asked about its function and labeled it variously a "hazard" and a possible "bumping post for the blind.” Inspector Taylor said that a pole had stood on that site for some seventeen years. The original pole was hit by a truck early in July, breaking the light bracket at the top and damaging the pole.

Note - This information on Recall Lights shouldn't be confused with information on Street Lights

Further - If you somehow found this page without having seen the Recall Light System page Click Here

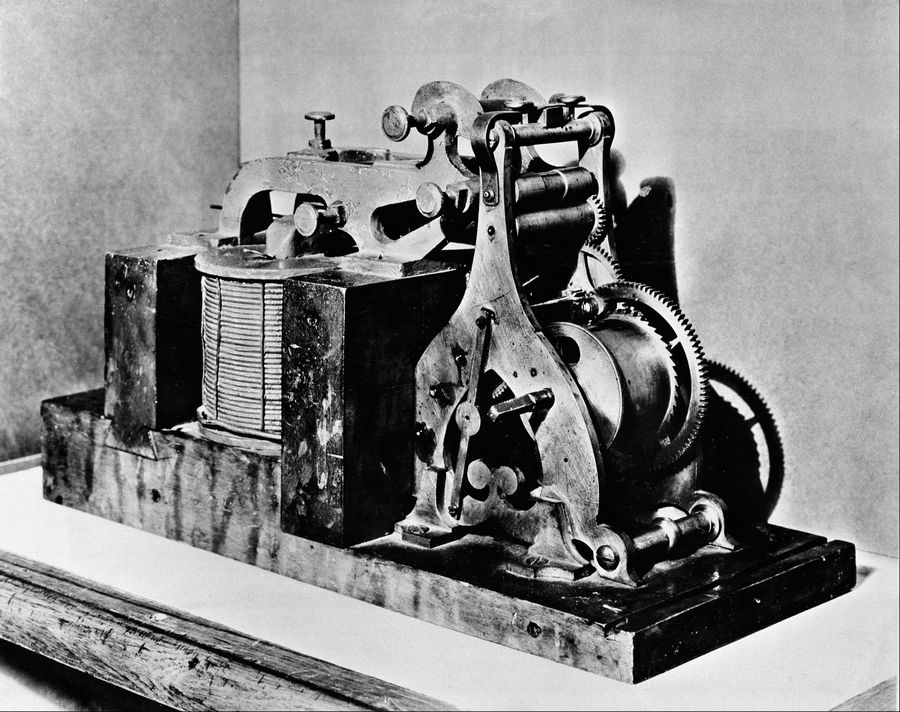

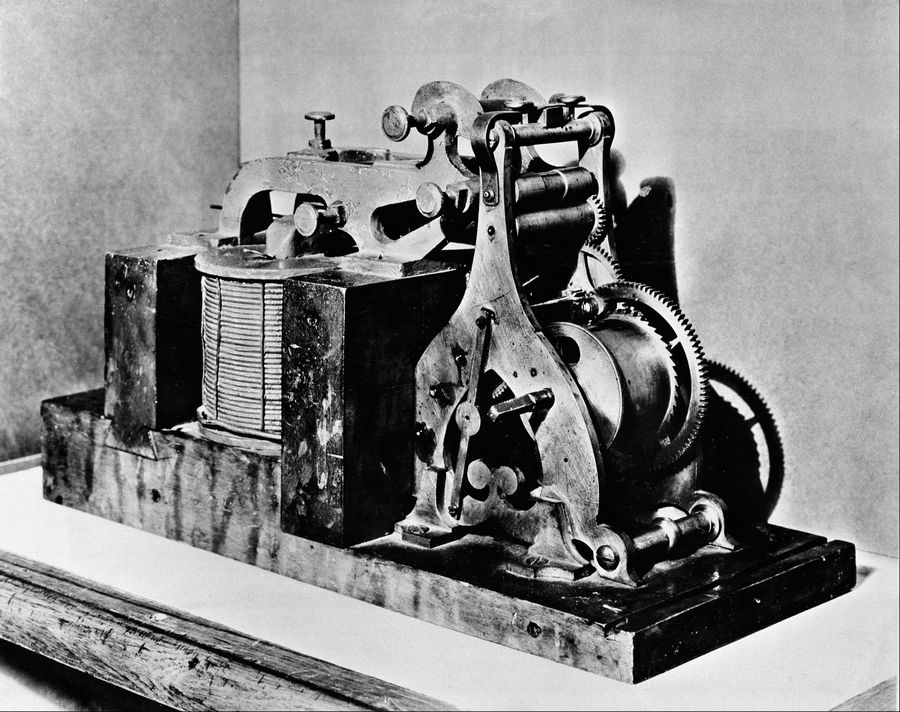

On on 24 May 1844 a Morse-Vail telegraph register like the one above was used to send and receive the message

On on 24 May 1844 a Morse-Vail telegraph register like the one above was used to send and receive the message

"What Hath God Wrought"

on an experimental line between Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, Md.

POLICE INFORMATION

Copies of: Your Baltimore Police Department Class Photo, Pictures of our Officers, Vehicles, Equipment, Newspaper Articles relating to our department and or officers, Old Departmental Newsletters, Lookouts, Wanted Posters, and or Brochures. Information on Deceased Officers and anything that may help Preserve the History and Proud Traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to Honor the fine men and women who have served with Honor and Distinction at the Baltimore Police Department.

Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. follow us on Twitter @BaltoPoliceHist or like us on Facebook or mail pics to 8138 Dundalk Ave. Baltimore Md. 21222

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll

You May Like

On on 24 May 1844 a Morse-Vail telegraph register like the one above was used to send and receive the message

On on 24 May 1844 a Morse-Vail telegraph register like the one above was used to send and receive the message