History of Baltimore City

A City of Many Firsts and these are the Beginnings

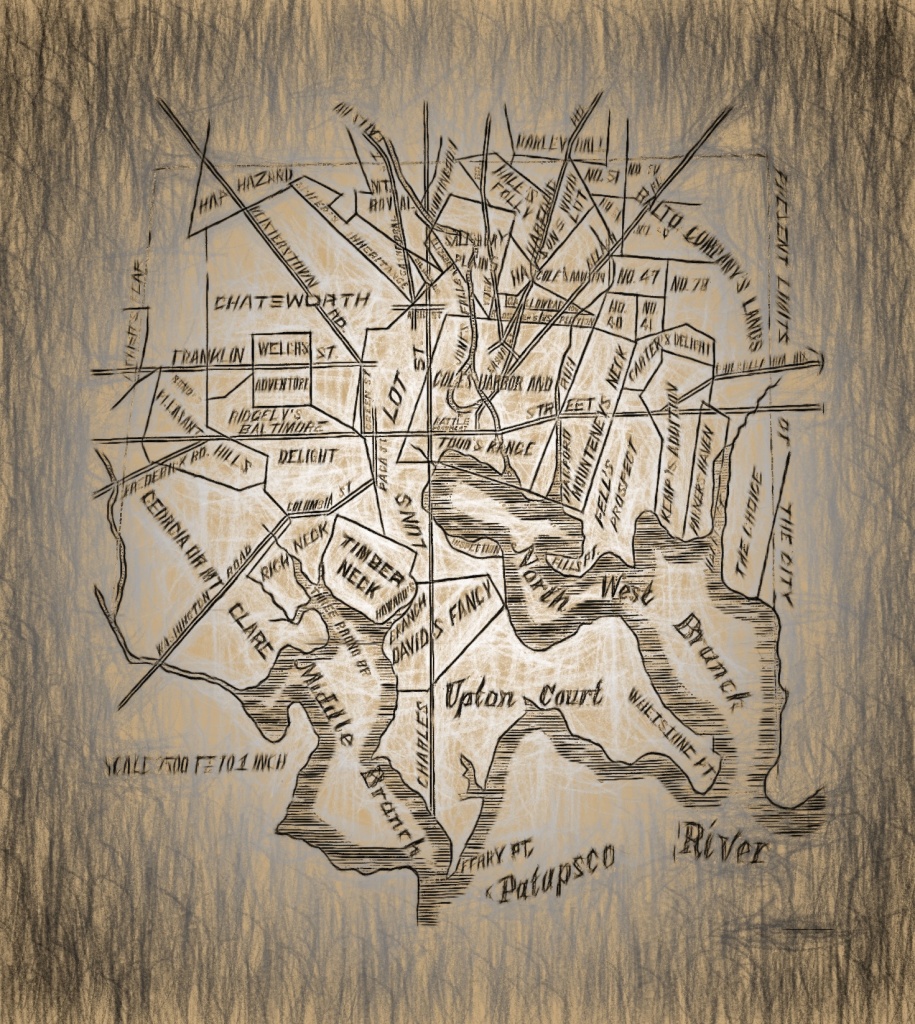

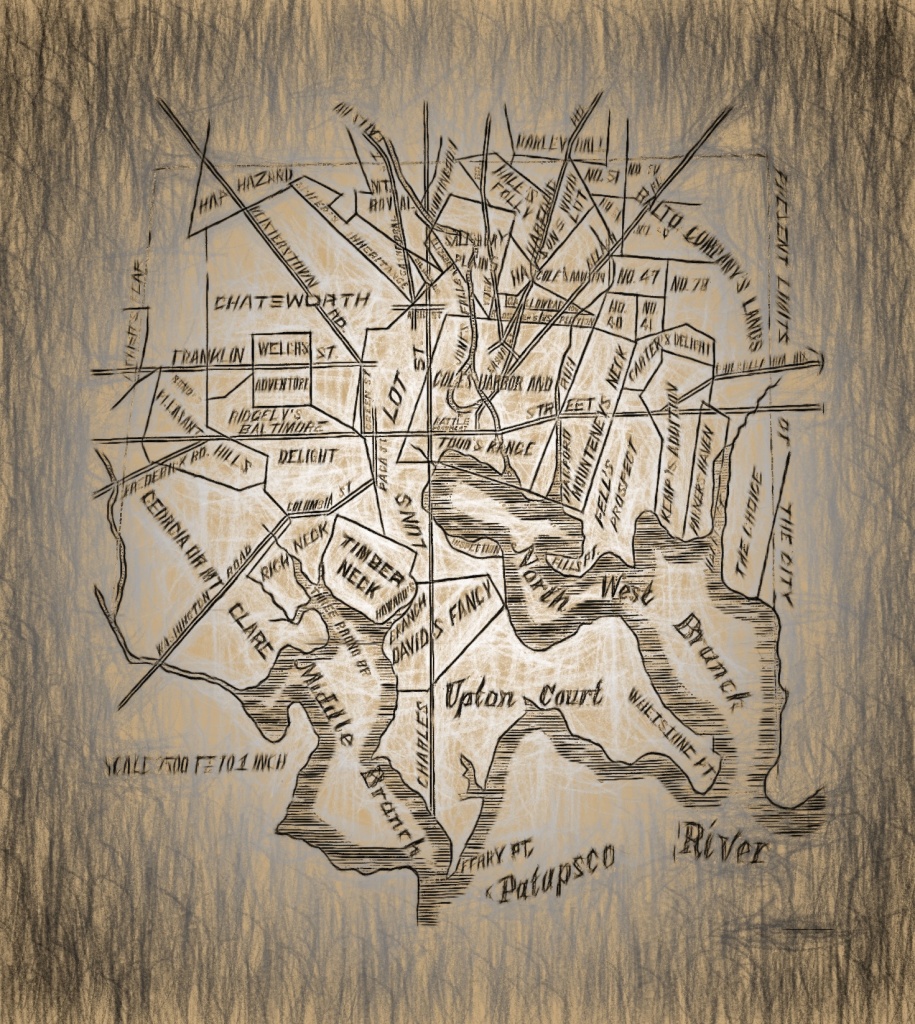

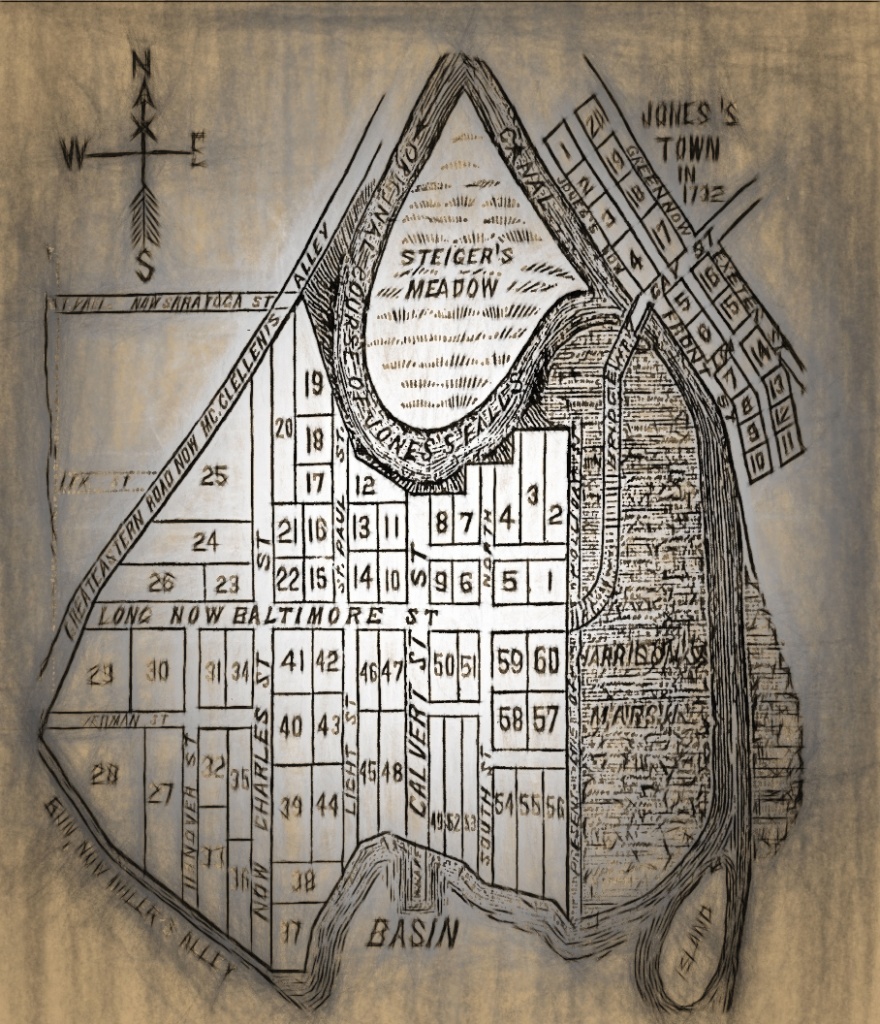

The accompanying map, which is reduced from the elephant folio map in the city commissioners office, presents, as far as possible within its reduced scale, the original occupiers of the land which is included within the present limits of Baltimore. Some streets and roads and other localities not laid down on the original chart have been introduced in the diagram for the sake of indicating localities more accurately. Beginning at Whetstone point, originally patented to Mr. Charles Goresuch, but escheated to Mr. Daniel Carroll, we find it next “Upton court” and “David’s fancy,” the property of Mr. John Moale. On the west and northwest is the Mount Clare estate of the Carrolls, where, later, Mr. Charles Carroll and his fine residence. Northeast of that is the estate of Chatsworth, which was originally the property of Dr. George Walker, clerk two and one of the commissioners for laying off Baltimore town. Between this and Carrolls property we find “Rigley’s delight” annexed to the town at the same time that Howards and Rogers additions were made; “bonds pleasant hills” and “Welches adventure,” of which we have no record. Eastward are “Timber neck” and “London’s lot,” property of Col. Howard, added to the city as specified in the article accompanying. The track called “Saulsberry planes” is the Howard homeplace, no later as “Belvedere,” and “Elizabeth’s diligence” sooner or later became part of this plaque. “Cole’s harbor” or “Todd’s range,” very accurately given on the map, was the original contract out of which “Baltimore Town” and “Jones town,” and many other additions were carved. “Darley Hill” was an old track, in which the friends very early purchased an interest, set up their meeting house and had and it still have their burying grounds. “Hansen’s would lot” was only a part of the Hansen mill site property, described elsewhere. “Mountenay’s Neck” was part of a patent of 299 acres originally granted to Alexander Mountenay, extending on both sides of the Hartford run into “old town,” this property, escheated by the Fells and others, was claimed by Mountenay’s heirs, and a good deal of litigation resulted. “Fells prospect” seem to have been an original patent, but out of “Carter’s the Light,” “Gallows Baron,” “Kemps addition,” “Parkers Haven,” and some other tracks we have no certain details.

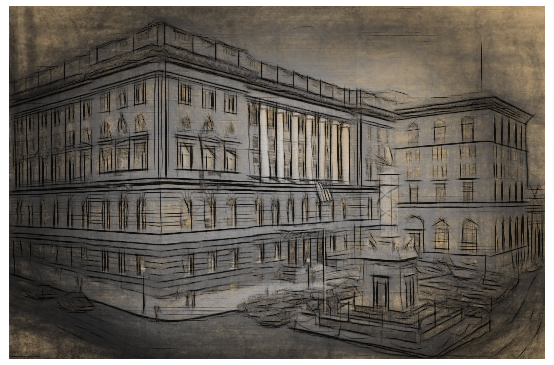

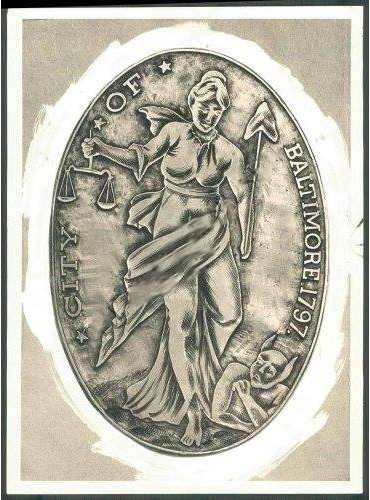

First Seal of Baltimore

10 January 1880

Monday, 12 January 1880 was the 150th anniversary of the actual founding of Baltimore- the following pages are from a newspaper article about those 150, now more than 285 years. On January 12, 1730, the first stake was driven into the ground for the survey of the original plats of this great city, which, unlike some of the mushroom cities of the West that presume to be its rivals, has a history as well as a future, a pedigree as well as great expectations. There can be no better guarantee of a glorious future than an honorable and reputable past, and this The Angels of Baltimore present unchallenged to the inspection of the world.

It seems fitting that such an anniversary should be kept with some degree of ceremonious observance – that is a duty equally of courtesy and respect to those venerable founders to commemorate such an occasion, and how better can it be done then by a brief historical review of their work? – That work into which, while perhaps indeed they “build it better than they knew,” they certainly put all the force of honest and earnest endeavor, and acumen and discernment in the choice of a loyalty, and the discovery of its present and prospective advantages for suppressing those of the founders of any other town on the Chesapeake Bay. It has seemed to The Sun that there could be no better time than now for the enumeration of some of the leading events and circumstances connected with the founding and establishment of Baltimore, and it is entitled to claim that the present contribution to the annals of the city, while it embraces many particulars not generally known, and reached, in fact, after a considerable volume of original research, has been severely tested, with a view to the most perfect accuracy attainable in such an article.

OF THE NAME, BALTIMORE

When George Calvert, gentlemen, of York Shire, had been dubbed night by James one, who was much fonder of paying for good service in such honors them in a coin of the realm, he was already principal secretary of state for Great Britain, and one of the most valuable officers attached to the crown. He was still no more than Sir George when he obtained his charter and found it his colony of Avalon, in Newfoundland, upon the mistaken theory that that island, with the same latitude as Great Britain, must possess an identical climate. In 1624, however, Calvert became a Catholic, and in his own manly way asked the king to release him from his offices, telling him of his change of faith. The king, who knew when he was well served and was a shrewd observer of character, [witness his reliance upon “juggling Geordie” Harriet, the Edinburg goldsmith,] was deeply attached to Calvert, and, while relieving him of his secretaryship, not only retained him in the privy of counsel but also raised him to the Irish peerage. Calvert, in selecting his title, close to becoming Baron Baltimore of County Longford. The town from which he took his title [by force of what memory or association does not appear in the records] is in the providence of Münster, County Cork, a small seaport in the extreme south of Ireland, over 40 miles from Cork, with some little coastwise trade, a registered shipping of 4000 tons in a population of under 200.

The title of Lord Baltimore has been extinct since the death of the last Lord, Frederick, 14 September 1771, but the name Baltimore seems to be in a fair way of enduring – Esto Perpetua! Besides Baltimore in Ireland and Baltimore in Maryland, and Baltimore County, there is a Township in Windsor County, Vermont of the same name, and there is a Baltimore in Hickman County, Ky., One in Fairfield County, Ohio, one in Barrie County, Michigan, one in Warren County, Indiana one in Joe Daviess County, Illinois one in Tuolumne County, California, besides a Baltimore hundred in Sussex County, Delaware. The name Baltimore, if we may be allowed to resort to the far-fetched analogy and assume an origin for the world, would seem to be singularly significant in respect both to the causes which led to the city’s founding and the circumstances inducing the belief of its perpetuity. In ancient Irish BALT means the same BELT, WELT, and MORE signifies “great.” The original Baltimore was seated upon a considerable arm of the ocean. The Baltimore of our love and hope certainly derives much of its commercial importance from its site and the most convenient and accessible part of that "great belt" of the scene known as the Chesapeake Bay, and under such circumstances, the equities and necessities of the case entirely apart, it would seem as if the city's determination to annex the "belt" of Baltimore County were a congenital and hereditary purpose, one of those forces which it is useless to resist.

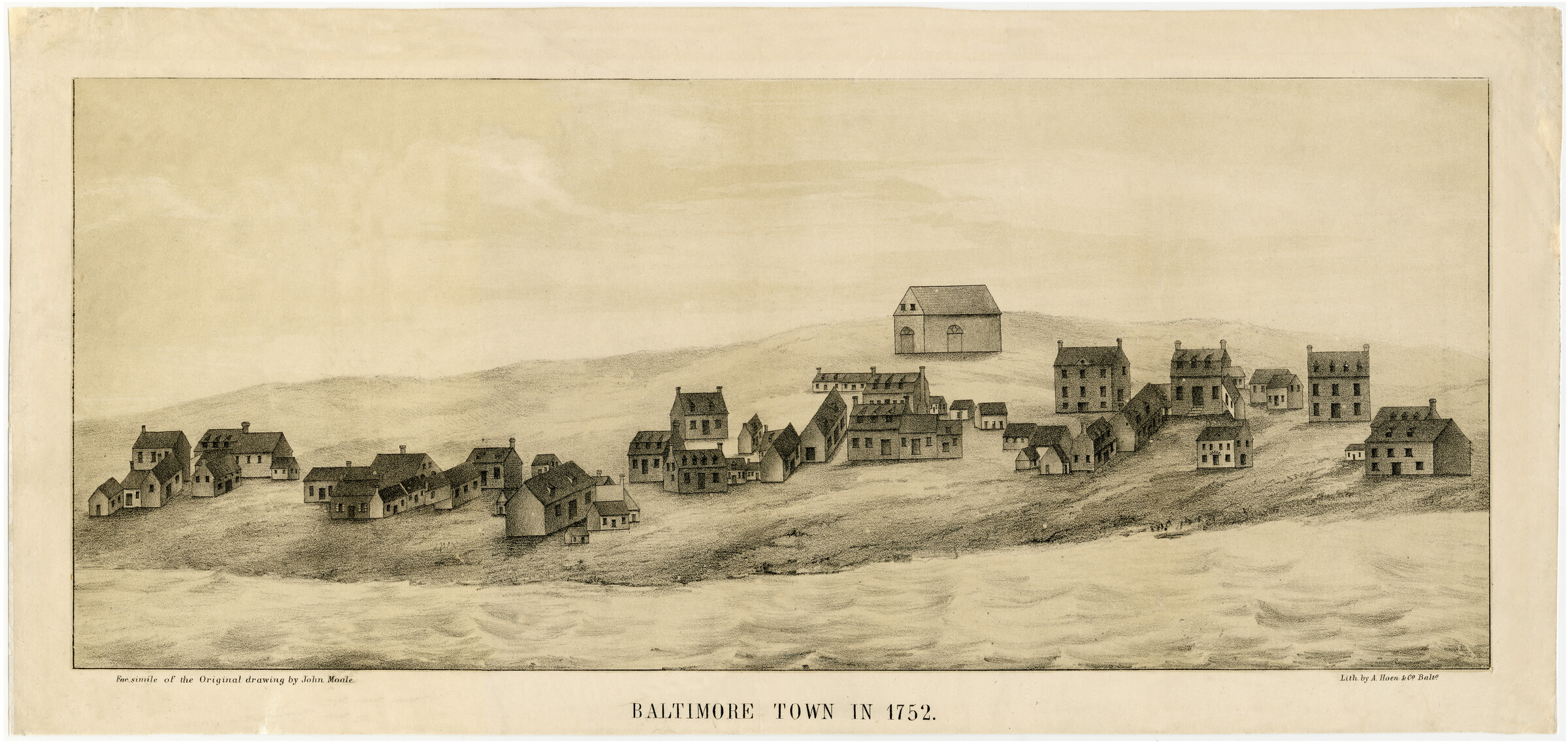

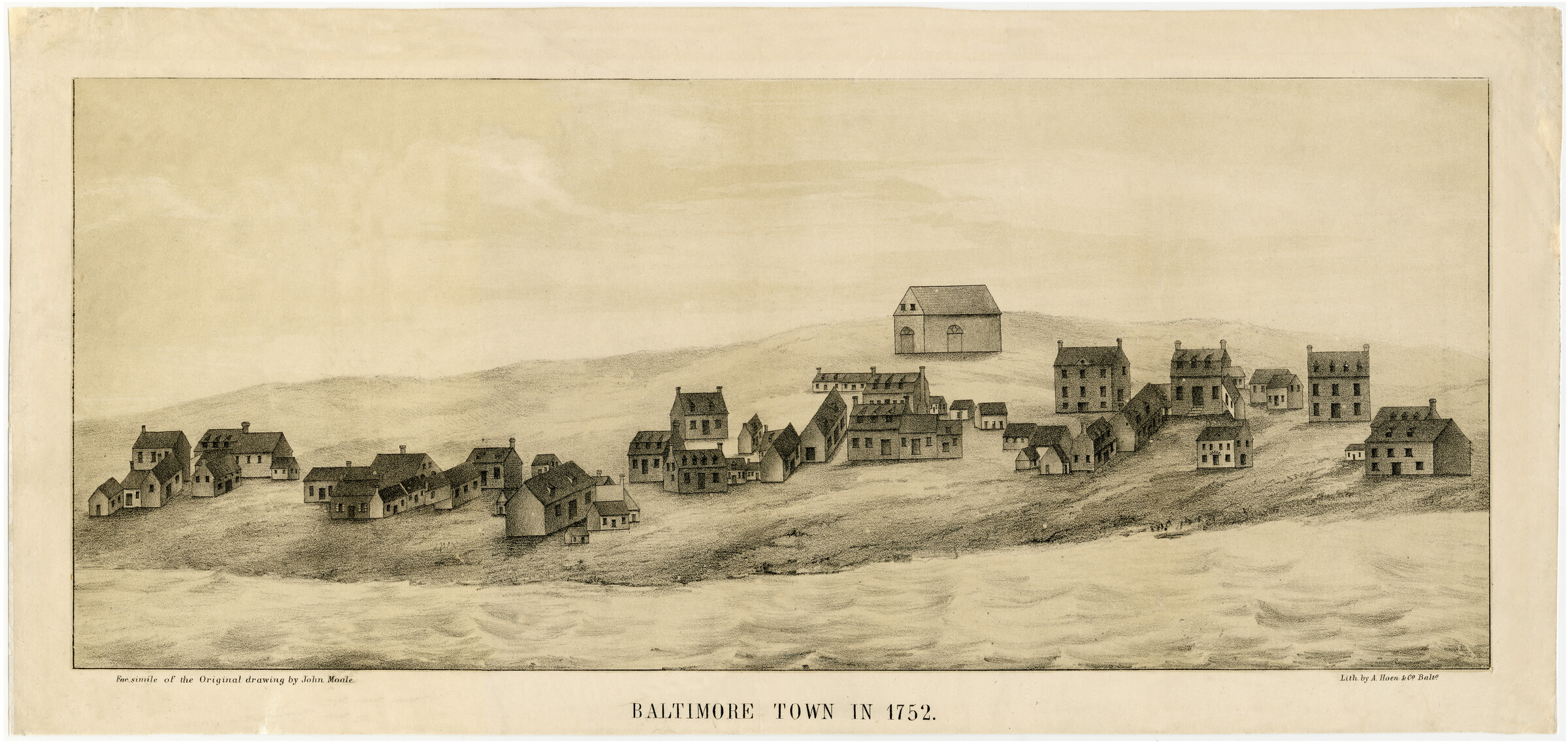

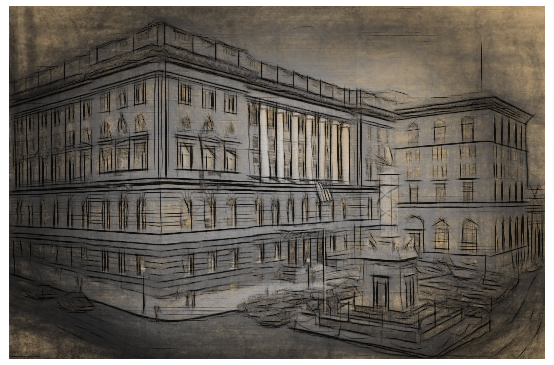

An undated facsimile of an original drawing by John Moale.

An undated facsimile of an original drawing by John Moale.

The above image depicts a very early Baltimore, Maryland, in the year 1752. Baltimore was founded on 8 August, 1729 There are a small number of houses and buildings atop a slight slope, with a larger square building in the background. The large building in the back could have been a representation of St. Paul’s Protestant Episcopal Church. St. Paul’s P.E.C. was Baltimore’s first church of any denomination and was completed in 1739. It was built atop Saratoga Street Hill, which was the highest point in Baltimore Town at that time.

OLD BALTIMORE IN MARYLAND

The city of Baltimore, it must be premised, however, is not the first nor the only town settlement to which the Lord proprietors name was affixed. In spite of the agricultural pursuits of the people of the province, their large plantations, and their essentially country life, the efforts to create cities and towns was strangely persisted in by the Gen. Assembly of Maryland, and the quantity of paper towns chartered, some of which were never even laid out, and nearly all of which have vanished utterly from the face of the earth, is surprising. All roads still bear their names, perhaps, but the objective point at which the roads aimed has gone utterly, leaving not a wrack behind. There are a dozen “JOPPA roads,” for example, in Baltimore County, but a search for JOPPA itself would be as fruitless as the guest for Atlantis or for the island of St. Brandon. Baltimore County was created in 1659 – at least it is known that at that date there was such a County, for land patents in the county, were in that year issued to Col. Utie, who gave his name to “Spesutia Island.” In July 1661, the Baltimore County court was held at the house of Capt. Thomas Howell. In 1674 there was a general act passed to provide each County with a courthouse, and we all know them very soon afterwards a courthouse and County – seat must have been erected in Baltimore County, for in 1683 – the date of the first act relating to towns – we find authority accorded by the legislature to lay off the town on “Bush River, on the Towson near the courthouse.” This town, the earliest County – seat, was on the east side of Bush River, near its mouth, and its name was Baltimore – Baltimore the first elder brother of the city we now know. The site of this premature capital has not been definitely ascertained, but it was somewhere within the eye-range of the traveler who crosses Bush River bridge on the Philadelphia Wilmington and Baltimore railroad. As the historian of Marilyn says: “tradition still attaches the name of “old Baltimore” to a spot about a mile south of the Eastern terminal of the present railway bridge on Bush River; though its annals have perished, and new stone now marks the site of this elder sister the namesake of the present metropolis of the state. We can only surmise that, after a placid existence of about half a century, this ancient Baltimore dwindled and faded before the rising glories of Joppa.”

Another Baltimore was christened but could not be made to exist. This town was provided for in a charter granted in 1744, setting apart a tract of 50 acres upon Indian River, and Worchester County, but the counties surveyor did not lay off the locks. The next year the town was directed to be seated on some more commodious and navigable part of the river; and, to make the story short, there is no evidence accessible to prove that this will – named town was ever seated at all. It was probably a stillborn infant, and in that respect, much luckier than some of the town ventures of the lands peculator’s of the period.

JOPPA

The next tentative County seat of Baltimore County and Emporium of Maryland was Joppa, which came very nigh being a success. A certain instinct seems to direct the seating of great commercial cities near or about the head of tied upon great streams. Ships which go to see like to rest in salt water, but must seek the products which compose their cargoes in freshwater regions. The compromise point is the head of tied – water. The Liverpool sits there, on the Mersey, London on the Thames, Philadelphia on Delaware, Bremen on the Weser, Hamburg on the Elbe – but the catalog is too long to extend your weight upon. When “old Baltimore,” on the Bush River, at the head of tied, began to fail and decay, the Metro polish – seekers went to the head of tied on the Gunpowder and established Joppa. It was a good roadstead; the approach was by means of a very broad yet place it stream, quite navigable for all craft which then came in; the site was salubrious – in short, Joppa was almost sure to be the place where the commerce of Baltimore County and the country back of it must center. It was much nearer to that ideal focal point of the county than Towsontown, Texas or Timonium was ascertained to be by vote in 1851. Baltimore County then included Harford County also, and the head of tied on the Gunpowder was very near the center of population. In an enumeration of voters, made even so late as 1770, to determine which end of the county was most populous, two polling places were set by act of the legislature – one at Baltimore town, the other at the head of Bush River. The vote established the fact that the upper hundreds or most thickly settled, and Thomas Cocky, Deye, John Paca, John Matthews and Acquilla Hall were elected to the legislature on that basis. Joppa, besides, a good shipping place for tobacco, the staple product of the colony. It received more tobacco than any other landing in the entire compass of the county. It was even the rival in this respect of Elkridge Landing. The lands about and back of it were much more strong and fertile than those near the several branches of the Patapsco. Aziz, indeed, were as a rule were sterile and wild, and utterly void of attractions to the husbandman. Where the low lands were flat they were ill-drained and lacked salubrity; all the upland country was scrubby in its forest growth and Baron and Rocky in the subsoil. The ore banks on the middle and south branches of the Patapsco, the clay deposits, the regions of “Bare Hill,” the “white grounds,” “the soldiers delight,” the rocky ravines of the Gwynns and Jones falls – all signified that it was a section sure to be uninviting to the farmer and planter. Indeed, Baltimore County was settled first by way of Elkridge Landing, by planters who eschewed the sterile lands near Tidewater and migrated my degrees across to the Gunpowder and the rich Harford hands by the lines of the fertile valleys which traverse the upper part of the county. From Elkridge one got by the old church and court roads, the roads to JOPPA and to Garrison forest church, (originally the “chapel of the ease” to old St. Paul’s church, in Patapsco neck, into the rich lands owned by the Worthington’s on the upper Patapsco, into the Greenspring and Worthington valleys, and thence further across to Long Green and Cockeysville. These were the lands which the Cocky’s, and the Deyes, the Worthington’s, the Tollys, Halls, Matthews, Ridgely’s, Merryman’s, Hammonds, Risteaus, Gists, Howards, Dorsey’s, Stansberry’s, Gittingses, Welshes, Randles, Maccubbins, Slades, Holmes, and hundred other old County settlers took up by degrees, in their necessary advancement from the worn, outlands of Anne Arundel and Prince Georges, carefully avoiding the sterile sites in and around the forks of the Patapsco.

Surely no one in his senses would’ve dreamed, in 1730 or 1740, of abandoning such a place as Joppa for such an unpromising site as Baltimore town, on the Patapsco. The former was created by an act of the legislature, and christened with a good deal of ceremony. It was finally chartered in 1724, when the courthouse, jail, and St. John church were already built and comprised some 21 acres of land, divided into 40 lots, the greater part of which were taken at the price of L 1 7s apiece, but some of the most substantial citizens of the county – Matthewses, Pacas, Sheradines, Dorsey’s, halls, lows, Hollingworth, Wards, &C. Joppa had a court street, a church Street, a high and low Street. They had a shipyard and some shipping, and a foreign commerce of consequence with Europe and the West Indies. Many of the county notables lived there and grow rich, and, during the Revolutionary war, JOPPA is a shipyard had the honor to contribute a man – of – war to the Navy of the United States.

Fruit Rium. Nothing now remains to Mark the site even of Joppa, save one old house and a few moldering tombstones, grown up with grass and weeds, and what was once the churchyard of St. John’s Paris church. But towns are not made, especially on paper. They are born and grow, as the poets are said to do, and, like beauty, have their own excuse for being. – Few have the presence which enables one to put down his stick and say, this is the place for a city, as Alexander of Macedon did when he found that Alexandria, after demolishing Tyre. Most make the mistake of going to the wrong place, the wrong side of the river or bay. This was the case with the British capitalist who, in 1750, having money to invest, after examining the advantages of all the growing downs in the province – Annapolis, Baltimore, Chestertown, Elkridge, Oxford – put his money in town lots in Charleston, on Northeast River, as the place which promised to become the great city of the Chesapeake.

THE SITE OF BALTIMORE

But it does not by any means follow from this that the growth and prosperity of Baltimore are accidental, or the JOPPA or Elkridge, Charleston or Georgetown could’ve done so well had they been similarly favored in the chapter of chances. Baltimore grew up almost without tutelage and in spite of the rivalries and jealousies of other towns in the province and elsewhere. It is, perhaps, possible to show why this happened:

In the 1st Pl., Baltimore had a harbor, while Elkridge, Joppa, the Bush River town and others only had landings. The basin of Baltimore was a natural harbor for the craft of the day, landlocked, placid, ease of access. Secondly, Baltimore had iron deposits of great value hard by, the working of which was actively pursued, and of course, attracted population and made trade necessary. Third, Jones Falls and Gwynns Falls and the South Branch of the Patapsco go with three of the best milling streams in the country. It is undoubtedly the case that the earliest settlers of this country hereabouts, after the original patentees, built Mills on Jones falls and made flour and meal, not only for home consumption but for foreign shipment. Fourth, as these small mills developed into merchant males they needed larger supplies of grain; thus Baltimore not only extended its trade with the bay but opened up a trade with the “backcountry,” and was found to be the nearest and best market for the farmers of Carol and Frederick County’s, as also for those further westward. When Baltimore became the ENT report for the rich valleys of Pipe Creek and Monocacy, of the Shenandoah and the Cumberland, its future was a short. It controlled the growing flour trade because it controlled the short lines of the grain growing sections because it had the milling facilities, the harbor, and the shipping.

That is examining a little further into the character and history of this site. It was not very closely inspected by Capt. John Smith in his peregrinations around the “Chesapeake.” In his narrative of his sixth voyage he speaks of the river 30 leagues north toward of the mouth of the Patuxent, “not in exhibited, yet navigable; for the red clay, resembled bole Armeniack, we called it Bolus.” This Bolus River was the Patapsco, but it does not appear that Smith ever was on the site of Baltimore, and spite of Bozeman’s assertion that he ate Maize with the Indians at the foot of Calvert Street. In fact, from the impression which the red earth seems to have made upon him, it appears likely that, the sending the bay from the Susquehanna, his pinnace entered the river above the Bodkin, and skirting the Anne Arundel store from rock point to Brookline, he was persuaded that all the soil on the banks of the bolus was read and ferruginous. It is doubtful, indeed, if Smith entered the middle branch at all, or was conscious that there was a North branch.

THE ABORIGINES

It is probable that if he had done this he would not have called the Bolus an uninhabited river. There certainly were Indians on the Patapsco, and it seems likely that there was a considerable tribe which hunted from Baltimore to the North branch of the gunpowder, and fish about the head of the basin. The fierce and powerful Susquehannoughs used to hunt through this region, and entered the Patapsco, as he entered the Severn also, in their great war canoes; but the indigenous race probably belonged to the more Pacific fishing Indians, just as the Patuxent and other bands did, and were off suits of the tribes whose chiefs seat seemed to have been at Yaocomico and Piscataway. This Patapsco band is called the Mattawas by some authorities and was probably in a measure subject to the Susquehannoughs. In 1661 and the Susquehannoughs were in allegiance with the province, and in that year the assembly ordered the governor to raise what force he could to aid the Susquehannoughs and arrayed against the Ciniquo (Seneca) or Nayssone Indians “that have lately killed some English at Patapsco River.” These Indians were hunters, but they were fishing Indians primarily, and not nomads. In the treaty of peace of 1666 between the Lord proprietor and the collective Maryland tribes, it appeared that they used to paint their faces, that they carried guns, bow and arrows, spear and hatchet; that they insisted on the privilege of hunting, crabbing, fishing and fowling being preserved it to them inviolate, and that they grew corn in a systematic way, for the treaty requires them to fence in their cornfields in order to protect them from the hall and cattle of settlers.

There are persons still living who can remember the last foreign remnants of the Mattawas of the Patapsco with great distinctness. They retired into the mountains and wilderness in summer, but in winter often came into the settlements debate, wrapped in their blankets, sad and silent stragglers out of the tragic line of march of the Grand Army of extinction. There were certain hospitable houses where they were fed and entertained and permitted to sleep by the kitchen fire. They were not ungrateful for these favors. In the morning, they have stalked away after breakfast, they would see cans with their hostess and hold up a finger or two, or it might be three. This was a sign that at the end of one or two or three weeks they will return and bring venison with them. These appointments were kept to the day and hour.

EARLY SETTLERS

As the Indians faded away the white settlers came in by degrees. As we have seen already, one stream of settlement payment into Baltimore County by way of Elkridge Landing; a second penetrated by way of Bush, gunpowder, middle and back rivers; and a third came by way of Patapsco, and it was not long before fourth began to enter the county from York and Lancaster, in Pennsylvania. Until 1659 Baltimore County simply the upper district, or “hundred,” of Anne Arundel, had probably many patents were taken to land in it. It was erected into a County by order of counsel about this date, and much of the land seemed to have been rapidly taken up, though probably not much was brought into immediate cultivation. The discovery of the iron ore deposits on the Anne Arundel side of the Patapsco must have tended to stimulate speculation in the land patents in Baltimore County. By the act of assembly of 1706 three new towns were authorized in Baltimore County – one on Whetstone point, where Fort McHenry now is; one at Chilberry, on Bush River; one on Forster’s neck, on the gunpowder. (This latter site was afterward abandoned in favor of the “Taylor’s choice” property, owned or leased by Anne Feiks, and would soon after was turned into Joppa.) The Whetstone point site came to nothing. It seems to have been bought by the Principle furnace company, whose chief estates or later in Cecil and Harford County’s, and whose property was confiscated and sold during the revolution, in 1781. In July 1659 at the same time that patents for land on the gunpowder and Bush rivers were issued to Col. Utie, of Spesutia Island, other patents for land on the Patapsco, near the present site of Baltimore, were granted to several persons, some of whom, as, for instance, the Gorsuches and the Coles, who intermarried with them, must have belonged to the society of friends. Robert the Gorsuch took 500 acres, Richard Gorsuches 500, Hugh Kensey 400, Thomas Humphreys (another Quaker) 300, William ball and Walter Dickinson 450 acres each, John Jones 200 acres, Thomas Powell and Howell Powell 300 acres apiece. Thomas Howell, Thos. Stockett, Henry Stockett, and John Taylor, Commissioners for the county, held County court at Capt. Howell’s house on 20 July 1661. In this year, also, Mr. Charles Gorsuch took up 50 acres on Whetstone point at an annual rent of 1 pound sterling, and Mr. Abraham Clark bought out the patents of Dickinson and Collett, and part of the lands of Gorsuch, with a view to establishing a shipyard, probably on Harris is a creek. Mr. Charles Gorsuch is patent having vacated at a later date, Mr. James Carroll got Whetstone point, at a rent of two shillings per annum.

We now approach familiar names and trend upon our native Heath. In 1661 Mr. David Jones took a patent (surveyed for him by Mr. Peter Carroll) for 380 acres of ground on the line of the North branch of the Patapsco, (ever since objurgated under the name of Jones falls,) and actually settled, for a time, at least, on his property, residing on what is now Front Street. Mr. Jones’s property was – a part of it, at least – subsequently annexed to the original Baltimore town, as will be shown hereafter, under the name of Jones town. “Mountenay’s Neck” was next surveyed and patented, a tract of 200 acres on both sides of Harford run, which Alexander Mountenay took up, but which was subsequently escheated by William Feil, though Mountenay’s heirs claimed it when it became of value, and much litigation resulted.

In 1668, 13 January, Thomas Cole, a Quaker name also, took off 300 acres on the side of what is now the basin. Coles track, which he ultimately increased to 550 acres, was patented to him in fee and common socage for the yearly rent of 11 shillings gold and an equal fee upon every alienation of the land. His property was subsequently the property of Thomas Todd, was called “Todd’s range,” and was least at the quilt – rent of 10s 2½ d per annum, or less than a farthing per acre. It would all of it rent today, for free, for a dollar a square foot. In June 1668, Mr. John Howard patented 200 acres in “timber that,” paying a rental of four shillings sterling.

OUR LEASEHOLD SYSTEM

it all to be noted here that the entire system of irredeemable ground rents, which distinguish Baltimore from nearly every one of her sister cities, is the legitimate and necessary consequence of the leasehold system set up by the property government in the pursuit of its endeavors to establish a colony and preserve its property rights at the same time. The very name itself of “proprietary government” tells its own tail. Calvert owned the province; its inhabitants were his feudal tenants, which held under him, paid him a half a yearly quit – rent, due and payable “at our seat at St. Maries, at the two most usual feasts of the year, namely, at the Feast of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and at the feast of St. Michael the Archangel,” (say April 1 and October 1.) and were liable to him besides for military duty. It is possible that Sir George Calvert, when he drew up to charters of Avalon and of Terra Mariae, had in view a period when it might be expended, if possible, to establish a sovereignty independent of the British Crown. At any rate, in coordinating the principles which should regulate his palatinate he secured to himself all the elements of sovereignty, excepting the only allegiance to the throne, and he dealt with all settlers and a right royal manner, leasing lands liberally to all, but selling fee – a simple to none, except in very rare cases. Cecilius Calvert, the true founder of the colony, probably only executed the plans laid down by his father. He encouraged men of property and consequence to come over by granting them large manners at moderate quit-rents, the number of acres in their holdings being regulated by the number of “taxable” in their family. These lords of the manor were absolute on their own estates, owing nothing but allegiance, rent, and military service to the Baron at St. Mary’s. Cecil Calvert besides retained a great many manners in his own family – several of each County – which were sublet it to tenants of small tracts, the purpose probably being too secure to the Proprietary in person a body of direct adherents who would be sufficiently numerous to hold the tenants and feudal lords of the manners in check. Estates were very generally entailed, and many obstacles put in the way of their alienation. It is only a few years since the entailed ceased up the Hampton and Doughoregan manners. Thus, the leasehold system became engrafted into the thoughts of the people, and the possession of land in fee was unfamiliar. Nor was it strongly desired, when rents were so low.

In 1766 the last Lord Baltimore, the unworthy Frederick, alarmed by the attitude of the people in opposition to the Stamp Act, and oppressed by debt, ordered his agents in the colony, Daniel Delaney, Gov. Sharp and Mr. Jordan, to sell all his manners and other lands in the colony, and 300,000 acres were at once advertised for sale in the Annapolis Gazette. The best of this property was disposed of at prices ranging from 20 to 30 shillings per acre and was bought by large proprietors, who held the fee and sublet it to tenants on ground rent. The reserved manners remained unsold, however, at the date of the revolution were numerous, and many large at least manners were still held under the original quit – rent payable to the Proprietary. The custom of perpetual ground rent was further enforced by the feudal exaction of “alienation fines.” This distinctly feudal fee was part of the contract under which the Proprietary lease out his lands, and by which the tenant found himself not to alienate his holding without the consent of the landlord, or, if he did so, to pay a fine equivalent to at least one year’s rent. If this find was not paid the transfer was void. This tax, laid from the earliest days of the colony, was continued up to the time of the revolution, and it had the effect to make short leases so onerous that few persons resorted to them. If a man every time he transferred a share of stock was required to pay to the state a fine equal to a year's dividend upon that stock, there would soon be very little speculation in the dividend – paying line of Sears. But this is practically the way in which the Proprietary government of Maryland taxed every alienation of fees, and the effect of it was to make the long-term lease system universal.

At the time of the revolution, it was estimated that the annual value of the Lord proprietary quit grants was 30,000 sterling. None of these were paid after the date of the Declaration of Independence, and in 1780 legislator wiped them out entirely as far as the Proprietary was concerned at a single blow, by an act of assembly, was declared that the citizens of Maryland, “from the declaration of independence, and forever thereafter, B, and they are hereby, declared it to be exonerated and discharged from the payment of quit grants” to the Lord proprietary or any other subject of a foreign prince, and that “the same shall be forever abolished and discontinued.”

In 1780 the confiscation and seizure of British property and the property of tories and refugees were declared, after considerable opposition, debts being accepted, and the estate of ex-Gov Sharpe (after a sharp Street is named) exempted. The losses of Henry Harford, the error to the Proprietary, under this act were put by him at 447,000 silver this being exclusive of his losses in w quit-rents – the capitalizing of which at six percent would be 500,000 silver so that Harford’s loss in the neighborhood of $5 million by the war, the British government only allowing him 90,000 and compensation. After the conclusion of peace, in 1783, Harford, Gov. Eaton, and some other loyalist came over to Marilyn and salt to regain their property. It’d changed hands finally, however, it was not to be restored. Eden tried to reassert his antebellum authority – but found it advisable to desist. Harford memorialized the general assembly, which replied that “we cannot, consistently with the duty we owe to our constituents, do, or suffer to be done, any act that has the most distant tendency to create a supposition that any power on earth can place the free people of Marilyn in the degraded condition of tenants to a superior Lord, a foreigner, and a British subject. We are also clearly of the opinion that the quitrents reserved upon the grants of the former proprietors were here ditaments, subject to all the rules and consequences of other real estates, and, therefore, cannot, consistently with law, be held by an alien; and that no part of the treaty of peace can give the smallest color to the supposition that these here ditaments, more than others, were saved and reserved. That the claim of the former Proprietary to quit – rents ceased upon the declaration of independence we have not the smallest doubt, and we think the legislator acted wisely in declaring that the payment of them, even to this government, should never be exacted and that the citizens of the state should hold their lands on equal terms with the citizen of the other states.”

Ground rents, however, were not abolished. They had only changed hands. They were a popular security, because lying against real estate, and constituting a lien upon the improvement and personal property thereon, at the same time that they were exempt from taxation. The people were not averse to them since the usufruct of land would be in this way enjoyed without capital. Capitalist naturally favored the best security in the world – the security by which the owner of the land lent it out at interest, paid no taxes, and secured his annual dividend in perpetuity by taking a lien upon all the improvements put upon the land by the tenant. Thus the system became engrafted upon the whole community.

One Charles Carroll received the great grant of manner lands from where Catonsville now stands to the Monocacy – of which a part is now the Doughoregan Manor – he extinguished the Indian claims and pretensions by the payment of 200 shillings and satisfied the feudal rights of the Proprietary at the annual quit – rent of 20 shillings cheap enough for attract of 20,000 acres of forest and field, including some very fat lands. This quit-rent was abolished by the act of 1780, but Mr. Carroll did not on that account release is tenants. There are still a great number of farms “upon the manner,” small holdings, from 50 to 400 acres, is the least ease of which are tenants in Proprietary, and have the right of sale and conveyance of their leaseholds – upon condition of delivering, on or before a certain day or date, at certain specified mills – a certain quantity of merchantable wheat. Some of these farms pay a rent of half a bushel per acre, some more, some less. In each case the tenancy is an estate – the rent cannot be increased, the farm is conveyed subject to the ground rent in Brussels; whether wheat is worth $.80 or 280, makes no difference. Numerous other vestiges of these manners all leaseholds may be discovered throughout the late by the curious in such matters. In the system under which they were created, we have the origin of the so-called nontaxable, irredeemable ground – rent system of Marilyn. The state itself was afraid to take up the here ditaments of which it had to spoil the Lord proprietary; but that which the states dared not do, large landholders easily ventured upon.

THE BEGINNING OF BALTIMORE TOWN

It was upon a detached portion of the great Carol state that the first planting of Baltimore town was made. It was the custom house that created Baltimore – in some measure – that is to say – precipitated its foundation. But for the need of the colony and the Proprietary government for revenue, it is possible that the colony would have got one for a long time without more than a seat of provincial government and some few County towns in the interior, such as Merrill Burrell and Prince Frederick. An agricultural, tobacco – raising community, such as the people of Maryland, did not need seaports. The tobacco ships came as near to the plantations as they could, received the staple and scowls and lighters – and bartered their goods for it to the best advantage they could.

In 1812, August 12, John Flemming, J. P. For Montgomery County, took the disposition of Alexander Hansen and his associates – victims of the Antifederalists’ riots in Baltimore and the city jail mob, in which Gen. Lingan was murdered and Gen. Harry Lee (Father of Robert E Lee) was cruelly beaten and maltreated.

But John Flemming got none of the lots into which the original Baltimore town was divided, although there were 60 of them. We are able to give the names of all of the original subscribers to the faith the Baltimore would sooner or later become a place on the map. The act under which the town was laid out was a liberal one. It provided that when the land was laid out, surveyed, staked and divided into convenient streets and lots, and the lots and numbered, the owner of the ground was to have the first choice of one lot and then the rest to be taken up at will, none take more than one lot in the first four months, and none but citizens of the county to take up any loss within the first six months. Lots were to be built upon within 18 months after entry, the buildings to cover not less than 400 ft.², (that is, say a house 20 x 20, or 10 x 40,) and all lots not taken within seven years to revert to the original owner of the land.

THE DEED AND TITLE

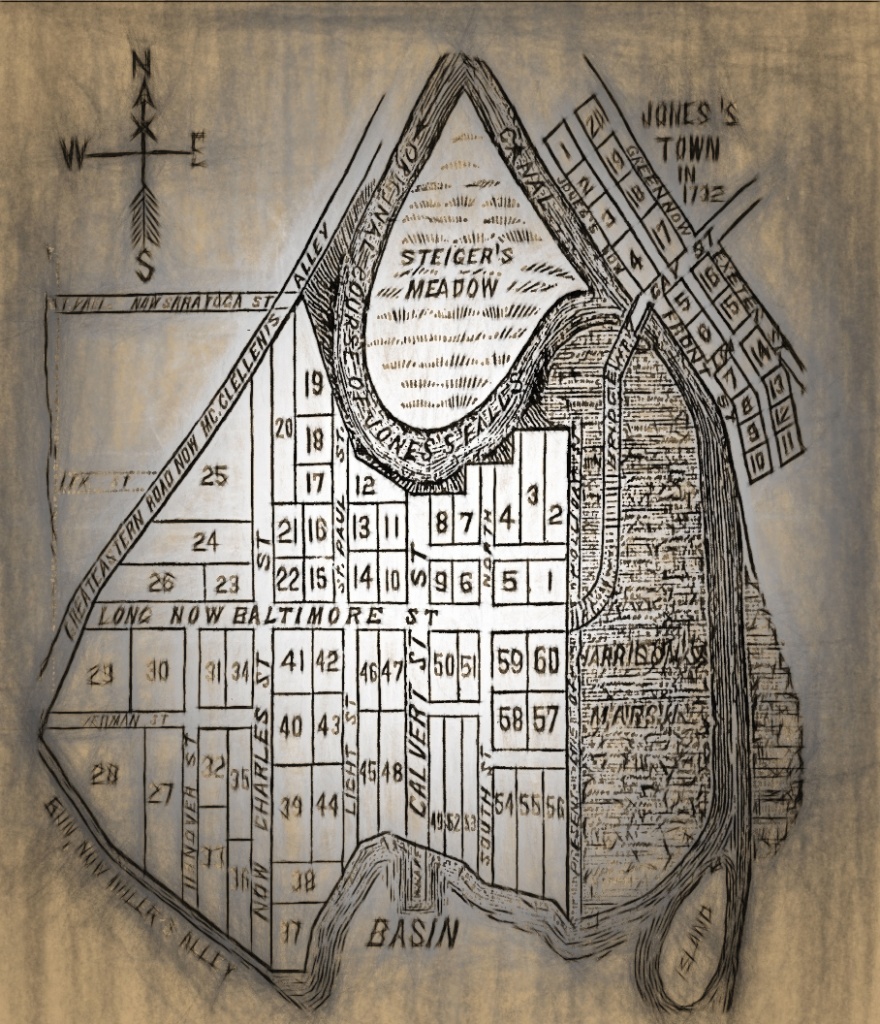

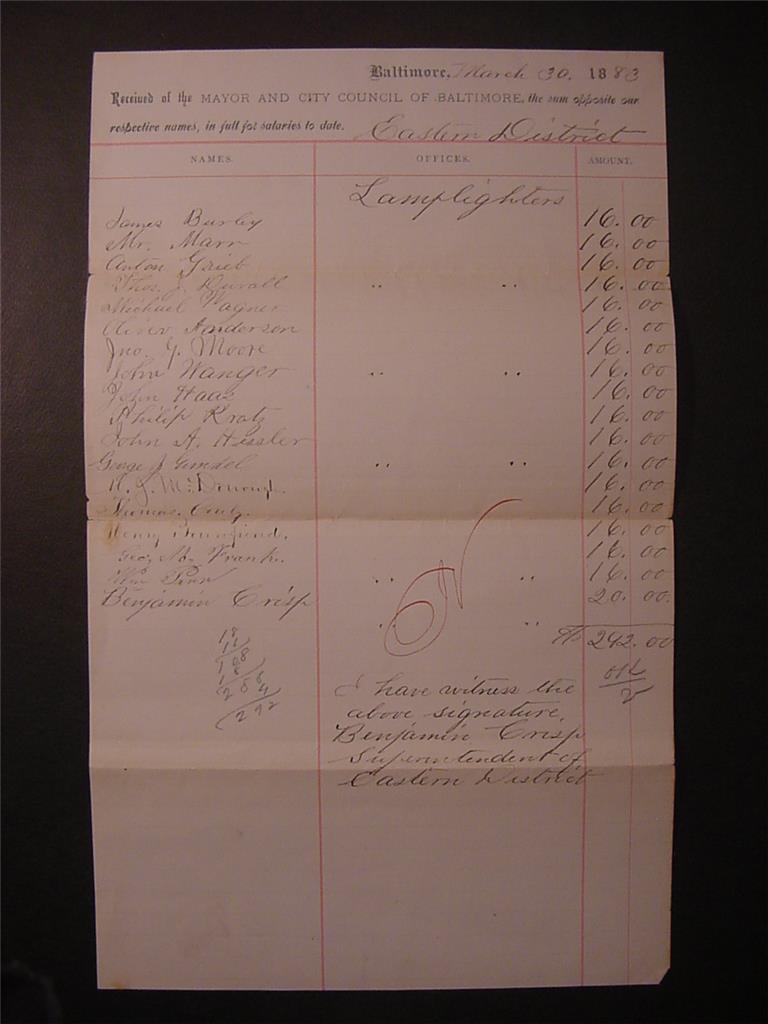

The commissioners were required to employ a clerk, who was to record all their acts and conveyances in a bound book, which same book was to be logged in the keeping of the clerk of Baltimore County court. On December 1, 1729, the commissioners struck a bargain with Charles Carroll, acting for himself and for his brother Daniel, then absent, for the purchase of the town’s site specified in the act of assumingly. The commissioners who signed the agreement were Richard Gist, William Hamilton, and Doctors Buchanan and Walker. The price agreed to be paid was 40 shillings per acre, and current money of Marilyn, or tobacco, warehoused with the sheriff of the county, at the rate of one penny per pound. The money or tobacco was made payable to the order of Charles and Daniel Carroll, their errors or assigns. The articles of agreement were duly signed by Charles Carroll and the four commissioners and were sent for record in the clerk’s office at Joppa. At this meeting the commissioners appointed the second one day in January 1730, the 12th day of the month, to meet the survivor of Baltimore County on Cole’s harbor tracked, and have the 60 acres set apart for Baltimore town surveyed and laid out.

LAYING OUT TOWN

On the day Mr. William Buckner, William having, Richard just, County surveyor George Buchanan and George Walker, five of the seven commissioners, were present, with Philip Jones, Deputy County Surveyor. Mr. Richard just was a commissioner and a County magistrate and did not see proper to act as a surveyor. Dr. George Walker was appointed a clerk to the commissioners, and qualified and was sworn in before Justice Richard Gist. The survey began at a “founded” on the water side, (the corner of the lot number 37 in the accompanying diagram) a spot not very far from the present corner of light and Pratt Street. The line then ran northwesterly until, about the intersection of liberty and German streets, it struck what was called the “Great Eastern Road”. If followed this line North East to a sharp angle on the precipice corner of Saratoga and St. Paul streets; then ran down the devious line of Jones falls to near its present intersection with holiday Street; thence it went straight in a line to the basin, and thence by the waterfront to the place of the beginning.

(Those interested in such matters may like to see the surveyor’s certificate. It is as follows: “Baltimore County, to wit: pursuant to the directions of the commissioners appointed by the act of assembly to lay out a town on the river, called Baltimore town, I,, Junior., Do hereby certify that I have laid out the same, beginning at a bounded red oak and running thence East five perches and one half; then north 21° east 10 perches; then northeast 19 perches; then north 69° east 12 perches; thence South 72 ½° east 22 perches; thence South 55° east 14 perches; thence South 30° West 23 perches; thence South 41 ½° West 17 perches; thence by a direct line to the place of beginning, containing 60 acres of land, more or less. Surveyed and laid out his 14 days of January 1730, me, Philip Jones, Deputy Surveyor of Baltimore County.”)

The lot was shaped like an Indian arrowhead, its point towards the West, the supposed fluke (number 19 on the map) toward the north. It was traversed by three streets: Long Street, (new Baltimore Street,) running East and West 132 ¼ perches, and 66 feet wide; by force Street, now known as Charles Street, running 89 ¼ perches North and South, and Calvert Street, running 56 ¼ perches in the same direction. There were also nine lanes, called South, second, lovely, light, Hanover, Belvedere, East, St. Paul’s and German lanes, each one perch in with and the various Lance. The terminus of Calvert Street on the south marked the riverfront, the basin then coming up to about the middle of Lombard Street (as it was afterward called) on the North. It is evident that the speculators in the new town fancied that Calvert Street was to become the main thoroughfare since it led to the water. The county wharf was built at its foot: it was named after the Lord proprietary family, and, when the lots came to be apportioned, Mr. Charles Carroll, who had the first choice, selected number 49, an acre, nearby on the northeast corner of the basin of Calvert Street, as will be seen by the Annexed diagram. The lots were numbered from 1 to 60, number one being a square acre Northwest corner of Baltimore and holiday streets; number two and three present City Hall site corner of East Lane and the city limits; number four, corner of Belvedere Lane (North Street) and East (or Fayette) Lane; number five corner of long (Baltimore Street) and Belvedere Lane; number six opposite this; number seven, in the rear of number six, to the northward, and so one. Number 19 was where St. Paul’s church was built; number 10 where the old museum used to stand, corner Baltimore and Calvert streets; number 59 where the sun building now is, but including much more ground also.

THE LOTS, WHO TOOK THEM

The first lot in Baltimore, as has been said, was taken up by Charles Carroll. This was on Wednesday, January 14, 1730. Philip Jones, the deputy County surveyor, was given the second choice and took number 37, corner of light and Pratt Street, and including the site of the present Maltby house. Mr. Jones probably paid for this lot with his surveyor’s fee. Jason Jackson, took number 38, on the waterfront, transferring it later to Samuel Peel; Dr. George Walker took number 52, adjoining Mr. Carol’s; Richard Gist took 48, on the other side of Calvert Street; William Hammond took 45, Mordecai price 55, Christopher Guest 56, on January 15 Thomas Sheridan, share of the County, took lot number 44; William Buckner number 53, and James Powell number 26. This one was on Baltimore Street, facing Hanover, and running back to McClellan's alley, yet Mr. Peril let it be forfeited rather than pay the 40 shillings charged.

The next day was Friday, but Charles Ridgely took lot number 54, on the waterfront, afterward transferring it to John Diggs, who built himself a house; Luke Trotten took number 36 transferred later to Mr. Jones, to a surveyor, who already owned the adjoining lot number 37. In the course of the next few days, several warlocks were taken up, some of which were forfeited afterward, but the rest built upon in compliance with the law. Capt. Robert North took number 10 (to museum lot), Richard Hewitt, number 35 (Southwest corner trolls and German Street) Capt. Sheridan (for use of his son) took lot 40. John Gorsuch number 51 on which Mr. Harris built (this is the lot where the American building now stands, one a half way up toward Calvert Street and all the way up to lovely Lane) David Robinson took number 47 on which Squire guest afterward built, Mr. John was still in built on a number 15, William Hammond built on number 46 and Martin Parlett took number 42 but forfeited it. On February 22, 1732, the vestry of St. Paul’s Paris (the original church of which was down Patapsco neck, near the intersection of the Northpoint Sollers point road) took up lot number 19 to build a church upon it. This same year 1731 Dr. James Walker, the clerk of the board of commissioners, took number nine and built. He also took part number 53 originally taken up by William Buckner; John guiles took number 39; Richard Lewis took number 11; Richard Gist number 59 (the sun’s lot) and paid for it, like a sensible man, thus owning three of the best locks in town; Rev. Jason Hooper (Rector of St. Paul’s) took number 32, and 1731, Capt. Sheradine having forfeited, and a subscription having been started to build St. Paul’s church, although it was not completed at this time. Shortly afterward Mr. Hooper took up two more lots, adjoining each other, and numbered 16 and 21, while Thomas Woodward took number 39. In March 1735 Mr. Richard gist took up a lot number 13 for a County friend, while a Mr. Hall acquired Capt. North’s lot number 10 November, same year, Mr. Hooper took for the use of Rev. John Humphreys the lot number 34, when the Southwest corner of Baltimore and Charles streets, and asked leave to reenter his own original first select the lot.

And so the record runs on at great length. It is not until 1747, however, that the big lots in Baltimore town began to be valuable enough public, Christine, to make it an inducement to citizens to escheat them when forfeited by non-compliance with the terms prescribed by the act and the commissioners. In that year, September 16, 1747, we find that Dr. George Buchanan and Capt. William Hammond two of the commissioners, Capt. Darby Lux and Mr. Thomas Harrison, (who gave its name to Harrison Street, and was an owner of Harrison’s marsh) asked to have lot number 36 (originally conveyed to James Powell and afterward assigned to Rev. Benedict for Dylan) made over to them, each taking an equal share. At the same time, we find Mr. Edward Fotterhill, who owns much property in and about where Barnum’s hotel now stands, anxious to have some vacated and forfeited lots entered to him. Those proceedings no less than a new names show consecutively that the new town had begun to grow at last. The lot number 50, Calvert and Baltimore streets, still remains the geographical center of the city and number 59 if legends do not error, where the leading newspaper of the city, the sun, is published, included also the site from which was issued the first number of William Goddard’s Maryland Journal, the first newspaper ever printed in Baltimore.

In 1726 Edward Fell had settled east of the Jones Falls. In 1730 his brother, William Fell, bought the tract of land known as Copus Harbor, build a house on the line of what is now Lancaster Street, and thus gave a name to Fells Point. That part of town, therefore, so long the jealous rival of the westerly city, was practically founded about the same time with it. Fells point was not, however, united to Baltimore until 1796. The directory of what was expressly called “Baltimore Town and Fells point directory,” then, in the act of incorporation, it was taken in under the name of “depart for the hundred,” receiving some special exemption from taxation in order to persuade it to comment within the limits of the city. In 1732, August 8, the assembly passed an act for the erection of the Jonestown, “a town on a Creek divided on the east from the town lately laid out in Baltimore County called Baltimore town, on the land whereupon Edward Fell keeps the store.” This was the beginning of “old town” a title still familiar to our cars, it was so-called, perhaps, because people first began to settle in that part of Cole’s harbor property, line between Hansen’s mill and Fells store so that, in fact of houses and people, “old town” is older than Baltimore town, Fells store was on front Street, Near Front St., Jonathan Hansen’s mill was about the present intersection of bath and holiday streets. He had bought the property 31 acres, of Mr. Charles Carroll in 1711. It was part of the original tract of Cole’s harbor, Mr. Hansen built a strong dam across the falls at this point and put up a substantial mill. The backing of the waters by this damn tended to flood what was afterward called Steiger’s meadow, and this, with the spongy condition of “Harrison’s marsh” below the dam, and the continued overflowing of Harford run, tended to make Baltimore and Old town both of them very sickly places. Mr. Hansen sold out his mill site in 1741 to Mr. Edward Fotterill – of whom mentioned has been made above – a wealthy Irish gentleman, who spent his money in Maryland and in the improvement of Baltimore town very liberally, only to have all his property confiscated during the revolution.

LAYING OUT OLD TOWN

The act of August 8, 1732, appointed major Thomas Sheradine, Capt. Robert North, Thos Todd, John Cockey and John Bering, commissioners to purchase and layout 20 lots upon the 10-acre tract designated. The commissioners met on October 28, 1732, appointed Dr. George Walker as a clerk and set the survey is, Philip Jones, to work, having first appointed a jury to discover the owner of the land. William Fell had already told them that he neither would nor could sell the land, whereupon the jury declared it to be the property of the infants of Richard Colgate, deceased, and I judged its value to be 300 pounds of tobacco per acre, or L12 13s, for the track, as given in the cut. When the survey was made there was some delay in opening the new town, not for entry. This was not finally done until July 20, 1733, when John Gordon took a lot number one and built on

Edward Fell took number 24; William fell to number six: Thomas Boone number five: Capt. North number two: Capt. John Cromwell number three: Capt. John boring number 17 and 18: John Cockey number seven some of the lots were not built on and Fell in or were reentered. In 1735 and 36 nearly all the lots taken were held by the Fells, but there are some new names also, as Thomas Matthews, Dr. Buckler Partridge, Thomas Taylor, John Connell, Mary Hansen, &c. In 1740 the commissioners decided to close out the unsold lots at 150 pounds of tobacco per lot, and they were soon sold, and, it is probable, soon built on. These were the first beginnings of Baltimore, on the site of singular difficulties, a site insalubrious, cut up by torrents and ravines, quacking was saltmarsh and fresh marsh, (were the melodies of frauds and mosquitoes could always be heard,) and Gert with hills which rose to precipices and seemed equally to defy travel and for big grading. It was a sight, however, of fording an excellent harbor, waters.

Have two fares every year, in May and October, visitors at which are exempt from the civil process. To guard against fires, householders are required to keep ladders tall enough to reach the tops of their chimneys. In may sessions, 1750, Capt. Ceradyne’s and Salai’s additions were made to the town, and bracing land to the north and east of Jonestown, and which was part of Mountenays tract and Cole’s harbor, owned by the children of Colgate. At October session, 1753, Joshua Hall’s addition of 32 acres was authorized. This was North and West of the original Baltimore town tract, connecting it with what was called Lunn’s lot, belonging to John Howard. At November session, 1765, Cornelius Howards addition was made to the city, including a part of his lines lot, especially the South Baltimore portion, Lunn’s lot, which extended from timber neck northward until it joined the Belvedere estate of the Howards, was a so-called from the original patent A, who sold the property in 1688 to George Eager, Jno Eager Howards maternal grandfather. There was a very fine park of ancient forest trees in a part of this lot between Fayette and Lombard, Howard and Pat the streets, and a family mansion just about the present site of the Eutaw house. In Warner and Hanna’s fine map of Baltimore, dated 1801, this plat of ground spoken of is marked off as a “public square” it was given conditionally upon the contemplated removal of the state government from Annapolis to Baltimore, but Col. Howard subsequently gave the city the Mount Vernon Pl. lot instead of this, at the time when the plans for the Washington Monument took shape and consistency.

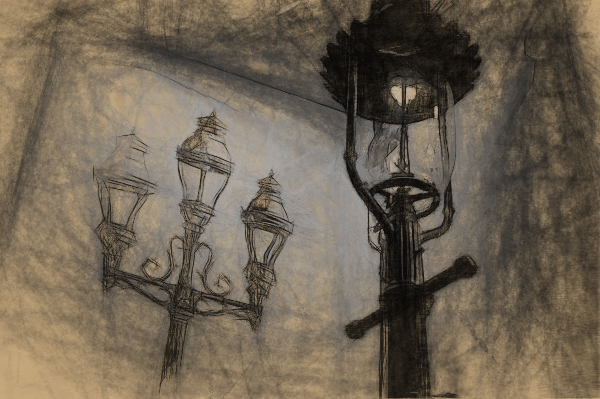

Harrison’s marsh was ordered to be drained filled and laid off, by the act of the legislature, in 1776. This secured the draining of all the “marks” market section of the town and added largely to its area available for settlement. These swaps, which were on both sides the falls, but chiefly on the West, were the property of Harrison, Philpot, and Plowman. They were a great nuisance and were declared so by the act of assembly, which likewise enforced their reclaiming. They probably paid the owners very well. In 1779 Mr. Harrison got an act passed to authorize him to lay out a new and amend the streets, lanes and alleys “in that part of Baltimore town commonly called the marshy ground.” Before this, in 1773, Fells and Plowman’s additions had been made to the town, Plowman’s being the tract east of the falls and south of York streets, (now E. Baltimore St.,) and Fells all his father’s purchases of Mountenay’s neck, and generally the land from York Street down to “the Cove,” part of what’s being on high ground, and comparatively healthy, grew to be quite an aristocrat quarter in the early commercial days of Baltimore town, when sea captains were rich, and all merchants had ocean ventures. Some of the old mansions in that quarter still and of the ease and luxury of those who dwelt in them, dilapidated as their present surroundings are. In 1781 there were further additions by Fell, by Moale and others, and’s diggers meadow, which had been drained by the enterprise of Englehardt Yeiser, was added to the town. It is still called the “meadow”. Yeiser, a man of pluck and energy, and one of the best of her early citizens married Catherine Keoner, granddaughter of Melchior Keener. In April session, 1782, John EAGER Howards addition was made to the town, and the same year Rogers and Ridgely’s addition. The same year a systematic plan for paving the streets was put into operation, lanes were widened, the hills cut down, wharves built. Port wardens were appointed in 1783; the next year the courthouse was underpinned and Calvert Street extended, and the town more carefully surveyed. The same session of the year provision was made for a night watch and for the erection of Street lamps in Baltimore town. In 1788 the markets were regulated by act of assembly, (the first market, built in 1761, standing at the corner of gay and market streets, the second being the marsh market,) and did the next few years are noticeable for many ask about paving. In 1793 another waterfront improvement act was passed, and in the same year, Baltimore town in Baltimore County was incorporated. In the 1800s the first water company was set up. In 1801 the letters that I was established; in 1803 the Lexington market was built, and in 1816 the last act to enlarge the bounds of the city was passed. Let us now look into some of those matters a little more in detail.

THE PROBLEM OF EXTENSION

The limits of Baltimore are no greater now than they were in 1816, yet it will not be denied the city has grown more rapidly between 1816 and 1880 than it did between 1730 and 1816. In 1752 Baltimore had 200 inhabitants, 25 houses, one church, two taverns, one brig and one sloop, owned in the town. There was one schoolmaster, one barber, one Taylor, one Teamster, two carpenters and a Cooper. In 1800 the city had a population of 26,514, and in export trade exceeding $12 million. In 1816 the population was over 50,000. Since that date, it has increased some 300,000. Yet while it was attaining its first 50,000 inhabitants Baltimore’s limits were extended by no less than 19 acts of assembly, relating to valid increases in the limits. Since 1816, during which its population has increased six times as much, it has been rapidly kept by the legislature within its ancient boundaries of 1816. Nothing could be more incongruous that such a way of doing business, and it may be added that nothing could be more injurious to the true interest of Baltimore. A city needs not only a place to stand upon but room to grow. Everyone doing business in Baltimore, no matter where he lives, has a common interest in this matter and should exert himself to see the civil right it, the press can do much in this direction, though possibly the editor of

THE FIRST NEWSPAPER IN BALTIMORE

Would not have exerted himself much on the premises. The first newspaper of Baltimore was the Maryland Journal, edited and published by William Goddard, the publication of which was begun on the Friday, 20 August 1773. After a good many ups and downs of various kinds, and after changing hands several times the Maryland Journal and the Baltimore advertiser (for that was its full title) was partly burned out in a big fire on the west side of Light Street, which consumed the Baltimore Academy and the light Street meeting house, and came near burning the fountain Hotel, opposite the Journal’s office, at that time number 1 Light St., must have been badly charred. This fire took place in December 1796. The Journal was suspended, resumed in a sickly way, but June 30, 1797, it finally expired for good and all. It left no successor. Though the name was indeed assumed in 1862 by Mr. rude be Maryland Journal, at Towsontown, and a newspaper in this city, which was first begun to be printed two years after Goddard’s paper became extinct, is understood to claim the inheritance of the old journal. The interval is too great, however, between the deaths of the putative sire and the first appearance of the bantling going not to cast suspicion upon the alleged paternity.

To be sure, some of the characteristic traits of Mr. Goddard, who found that the Maryland Journal, is to be detected in the character of the assumed descendent; but these must be accidental, for Mr. Goddard left the Journal in 1792 and returned to Rhode Island whence he came. William Goddard was rather clever with the pen, made a good enough newspaper, and was full of speculative enterprise. He came to Baltimore in June 1773, having been editor of the Philadelphia Chronicle, a weekly from 1767 to 1773. This was a Tory Sheet and Goddard was himself a Tory, as his Maryland Journal proved. But he was something else besides. In his Chronicle, under date of February 10, 1772, he published a communication about the prospects of Baltimore as compared with those of Philadelphia. As regards the Former Pl., Mister Goddard’s paper was half Jeremiad, half liable. Baltimore, he said, had already reached her ne plus ultra‘s roads were so bad they afforded no access to the back settlements. It was badly located. The basin was filled up. It could never have any foreign trade. The laws were unfriendly to commerce, it was dropping to ruin in every way, and in short, Baltimore was the best town on the continent to get away from. In a brief year, Mr. Goddard was getting away from Philadelphia and seeking a maintenance in the Baltimore which he had just been traducing. When he came to Baltimore, on solvent and helpless, he was encouraged to go on, and in his journal came out on the day and date named above. The first number – a copy is before us – is a little gray and dark with age, beautifully printed on stout paper in good clear type. The Maryland Journal was a weekly, and the salutatory and today suspended for kicking ribbon the nuts promise much. The printing office is said to be on Market Street, opposite the coffeehouse. Fielding Lucas’s “picture of Baltimore” (1832) says it was printed from an office east side of South Street, near the corner of Baltimore Street. The coffeehouse seems to have been on the northeast corner of North and Baltimore Street. In 1796 the office, as we have seen, was on light Street. The original office, it might appear, was in a building now covered by the sight of the sun does not on that account claim to be the Maryland Journal successor an heir.

Mr. Goddard promised that his papers should be “of no party, and will be carefully supplied with the news, but on failure, to anecdotes of that sort the room will be supplied with such moral places from the best writers as will conduce most to inculcate good principles and humane behavior.” There is next a longish, heavy looking at a letter from the Bishop of C. To the Earl of Belmont, on his late duel with Lord Townshend, filling two solid columns out of less than 12 in the whole sheet. It then follows high a column of “moral pieces” and to scant columns of foreign, domestic and local news, including a notice of misdemeanors marriage to Mr. Englehart you nicer, and a brief price current. There is a communication in regard tithes and poll tax, Mr. Chase and Mr. Packer, written evidently by a clergyman, (their assigned “Hononchrononthotontogos,”) and a “political chronology” from Cecil County, in very poor verse, then there are some advertisements of tradesmen, tavern keepers, and &c., And Mr. Rathell, formerly of Annapolis, (where he tried a circulating library and failed) and of Philadelphia and Lancaster also, advertises himself as private tutor and “finisher” of young ladies and gentlemen. Mr. Rasul tried the circulating library business likewise in Baltimore, but he was no Mudie, and he failed. On the last page of this interesting sheet, Col. George Washington, of Mount Vernon, in Virginia, advertises that, having obtained patents for upwards of 20,000 acres of land on the Ohio and the great Kanhawa, (sic) he proposed to divide the same into any sized tenements and lease upon moderate terms, specifying conditions, advantages and &c., with great particularity. Person warning information may apply to the subscriber, near Alexandria, or, in his absence, to Mr. Lund Washington. Bernard Riley, living near Joppa, offers L 10 reward for the capture of his runaway servant man, Edwin McCarty, aged about 45, who was a soldier in some part of the country at the time of Braddock’s at the feet. Ellen has a score under his eye and is clad in country mail close. David Evans, clock, and watchmaker, (from Philadelphia,) has opened shop at the sign of the arts dial and watch – on Gay Street, and Christopher Hughes and company., goldsmiths and Jewelers, at the sign of the cup and crown, corner of market and gay streets, offer a neat and elegant assortment of plateau and jewelry. They also want an apprentice. After Solomon Bonhomme notifies the public that he rides post from Baltimore to the town of Frederick, (once a week) from whence another post rides to the town of Winchester, in Virginia, “those having any commands may depend upon having their business faithfully executed.”

We have given the contents of this first Lang of Baltimore journals with some detail. Goddard made a success at the start, he was full of work. He set up a special post to Philadelphia, and sought to establish “an American post office on constitutional principles, “and occasionally had a mall system at work in less than a month from Maine to Georgia. Paper getting scarce in November 1775, he set up a paper mill of his own. But he was a week, unreliable, treacherous man. He was twice mobbed, by the Whig Club in 1776, and by the town people in 1779, in the latter case for having published General Charles these “quarries” amid advertising in Washington. He was indicted for publishing a liable of Leonard harbor all on “kit” Hughes, the goldsmith, but was acquitted. He left the Journal in 1792, having a falling index, and, as we have seen, withdrew to his native state. The end of the journal has been given. It deserves a better fate, perhaps for Goddard was active and energetic. On 19 February 1783, he published an extra, “the Olive,” announcing in advance of any paper in the country the signing of the preliminary articles of peace at Paris, the news coming directly by a Baltimore clipper. Enterprise of this sort was so unusual that it deserved success.

GLIMPSES OF OLD BALTIMORE

Mr. John Moale’s picture of Baltimore in 1752, now in the historical society room, is a treasure of great value. It would have been worth nothing as per trade in the town, however, as it was 10 years later, and 20 years later Baltimore had got to be quite a place. It’s Mills were numerous and busy; it has a large foreign trade with the West Indies and with Europe; above all, it had retrieved a great session of active, enterprising citizens from elsewhere – thrifty Germans, from Pennsylvania or from Fatherland; French, from Acadian and the West Indies; Scott Irish, from Derry; Iris Gentry, from other places. It was men like Fotterill, Stevenson, Patterson, Harrison, user, Stiegler, fit, Keener, Reinecker, Eichelberger and their stamp, no less than the natives of the country, who gave Baltimore at an impulse to grow. These people traded with the world, and their busy craft, when the war of 1775 broke out, turned privateers, and enriched them in the town with the spoils of British commerce. The county seat was moved from Joppa to Baltimore in 1767, and the towns “boom had begun. Yet it must have resembled anything else than a city. The hills were not cut down, the streets were not paved, the houses were poor, mean and irregular. Mr. Robert Gilmor, in his reminiscence, mentioned that he caught crabs with the stick while walking around the waterfront from Jones falls, via Lombard Street, to Charles and Leo streets, (the foot of the latter being called “deep point;”) that he learned to swim in Jones falls at the corner of Calvert and Lexington streets, boats coming up to the powder House, which stood at the foot of the precipice on which the courthouse was erected, and that in the Revolutionary war he saw a mounted bugler swamped in the quad Marr in front of where the sun office is now. Calvert Street then ceased at the south end of Fayette Street; there was no Holiday Street on account of the falls and Stiegler Meadow; there was good suiting of snipe and Woodcock on Harrison’s Mars, where the center market now stands; there was a middleware the gas house now is, and Englehart you guys are had not yet cut that the now through Steiger’s Meadow, which diverted Jones falls from its old horseshoe Bend into the present bed. When the old courthouse was built (on the site of battle monument) the bluff at St. Paul’s and Fayette and Lexington Street extended on to Calvert, then descended in an abrupt precipitate no to the falls, and the courthouse stood sheer and toppings upon the very edge and comb of this bluff, until, by the ingenuity of Mr. Leon harbor all, (afterward a town Commissioner,) it was, in 1781, underpinned and arched in the street open. At that time the arts under the courthouse was supplied with stocks, pillory and whipping post, and justice straddled over the city’s center like Gulliver in Lilliput.

There was little attempt at grading or getting eight definite coordination of levels. The houses and styles of buildings were as irregular as the streets and wharves. The portrait of the town taken about the time of Mr. Harbaugh’s producer’s feet adds a spice of vivacity to the manifest accuracy. “It was a treat,” says this writer, “to see this little Baltimore town just at the termination of the war of independence – so conceited, so bustling and dominator – growing up like a saucy, chubby boy, with his dumpling cheeks and short, grinning face, fat and mischievous and bursting incontinently out of his clothes and spite of all the allowance of talks and broad salvages. Market Street had shot, like a Norm Berg snake, out of its toy box as far as Congress all, (liberty Street in Baltimore,) with its line of low browed, hipped roof wooden house in disorderly array, standing forward and back, after the manner of Regiment and militia with many an interval between the files. Some of those structures were painted blue and white, some yellow and here and there sprang up a more magnificent mansion of brick, with windows like multiplication tables and great wastes of wall between the stories with occasional courtyards before them and reverential Locust trees, under whose shade mimics a truant schoolboys, ragged little Negroes and grotesque Jiminy sweeps “guide to copper” and disport it themselves at marbles.”

The evident truth of those details about the houses of the town is confirmed by the message of Mayor John Montgomery to the City Council of the date so recent as to January 1826. He shows that even then, of 10,416 houses returned by a schoolmaster, 101 only were of four stories, 1608 were of three stories 1524 being of one story, whilst 7183, seven pants of a whole, were only two stories high. In James Robinson’s Baltimore directory of 1804, when the “city” was eight years old, Howard’s Park, trees and all, began at Saratoga Street, the West and stopped at Paca Street, and the separation of Fells point from old town was complete. The “Cove,” south of Alice Anna Street, had begun to be filled up, but the swamps of Harford run were two blocks broad, and will Street (Eastern Avenue) was a “causeway” indeed. The “meadow” was still unfilled, though Yeiser's canal had been cut, and there were half a dozen mills on the line of the falls from the Gay Street Bridge to Col. Howard’s place at the Belvedere.

There was pretty good living in town, though, in those days, and some excellent taverns, besides ordinary and coffeehouses. The assemblies were popular and recherche; there were two or three theaters, as there had been off and on from very early days, and the amusements were first-class. As early as 1773 Douglas and Holland played in the large warehouse which stood corner of Frederick and market streets; a theater to accommodate equally to old town, Baltimore town and Fells point people, was built in 1786 corner of Albemarle and Lombard streets, and in 1782 a brick playhouse was built on York, (E. Baltimore St.,) opposite exit or Street. We now and wrangle built the old holiday Street theater and opened it in 1794, the old “mud” theater, the real name of which was first “the Belvedere” and afterword “the and Delphi,” was a classic amphitheater that stood (and still stands) corner of Saratoga Belvedere (North) streets, were many excellent performances or had in the old days.

CHURCHES

And mold drawing of Baltimore we see but one church, St. Paul’s parish church, which stood then on Lexington Street a little east of Charles, facing towards Baltimore Street. A church was authorized to be built by the vestry of St. Paul’s in Baltimore town by act of assembly of 16 June 1730 as we know by the late Rev. Eston Allen’s researchers. The first a lot was chosen was on the old York road, near Walsh’s 10 yards; then it was decided to build on Mr. Edward Fells Pl., East of the falls, but finally lot number 19, in Baltimore town, was chosen, and the church completed here in 1739. The successor to this church, which was of wood, was built in 1779.

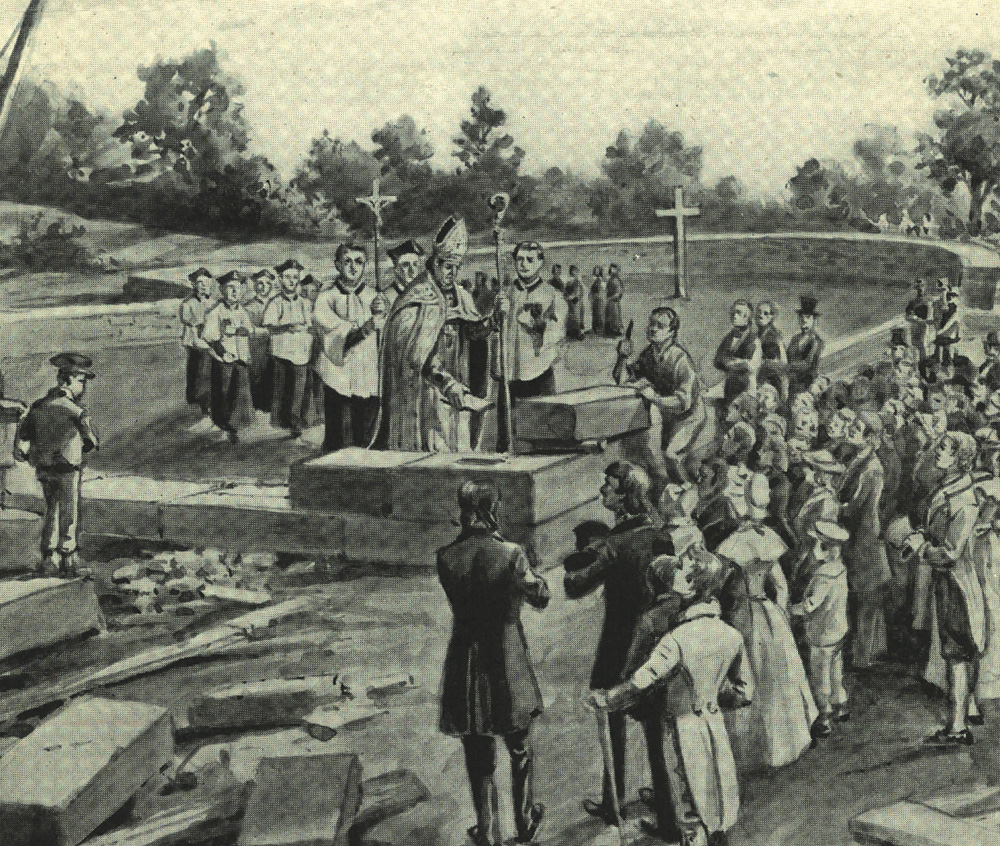

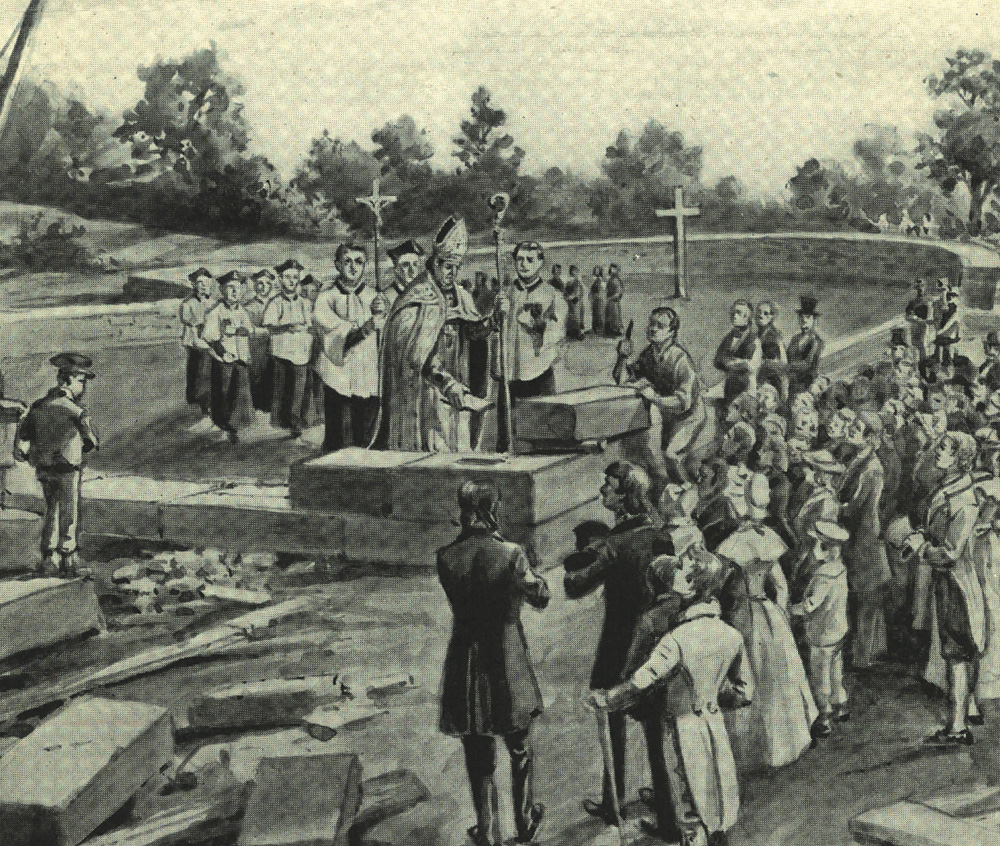

The oldest Catholic church in Baltimore was St. Peter’s, occupying the site of Calvert Hall, on Saratoga Street. This was a chapel built in 1770; built they are used to be services in Mr. Edward Fotterill’s house, on Calvert Street, as far back as 1756. St. Peter’s was enlarged and became the Episcopal Church of the diocese until in 1806 Bishop Carol laid the cornerstone of the present Cathedral. St. Patrick’s was founded in 1792, and is church building was on apple alley, near will Street, a small building, which has since disappeared. This congregation first worshiped an un-plastered room in the third story of a house corner of Fleet and Bond Street.

The first German Reformed Church was built in 1756, 1 North Charles St., about the site of the Young men’s Christian Association built in. This congregation subsequently, in 1772, erected their church on Second Street, where the old town clock used to be, and there it stood until pull down to make room for the opening of holiday Street. The first Lutheran Church was built in 1758, on First Street, (now Saratoga) where the African Bethel meetinghouse now stands. The earliest Presbyterian Church in Baltimore, founded in 1763, was a small log building on Fayette Street, near gay, and immediately on the bank of the Jones Falls. This was sold two years later, and a lot corner of North and Fayette streets, where the United States Courthouse now stands, was bought, Dr. Patrick Allison was the first pasture, and he was succeeded by Dr. James Ingalls Lewis, father of the late Judge Engle us Chief Judge of the orphans court.

The First Baptist Church in Baltimore was built in 1773, on the corner of front and Fayette streets, where the shot tower now stands, but in 1817 the Congressional removed to the church corner sharp and Lombard streets, so long spoken of as the “round” church. The first meetinghouse of the Society of Friends was built in 1780, corner of Fayette and Asquith Street, and is still standing but the Patapsco meetings used it to meet as far back as 1703, in a house standing on Harford Road just beyond the city limits, where the Quaker bearing ground now is. The earliest Methodist Church in Baltimore was built in 1773, in Strawberry Alley, a lane running north from Alice Anna Street, between Bond and Caroline St., Fells Point. The next was built in 1774, one lovely Lane, and was afterward succeeded by light Street meetinghouse, opposite the fountain in.

COURTS AND COURTHOUSES

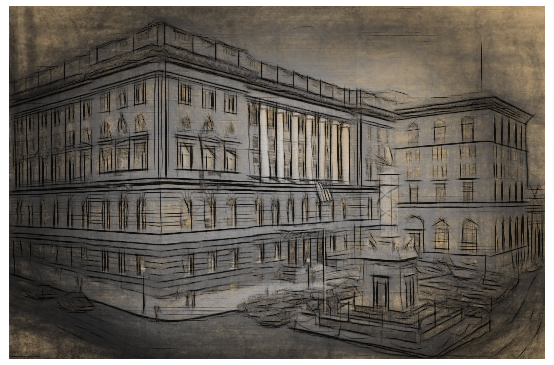

Baltimore city in old times was in Baltimore County, and the courts were the county and state courts alone. The county seat was removed from JOPPA to Baltimore in 1767 and then was erected that quaint building already describes, which when the bank was cut down from around it, rested upon the arts like justice on stilts. The courthouse on the present site was built in 1806 to 1808 in the old courthouse pull down in 1809. The new courthouse was burned down in February 1835

Our ancient courts were held at St. Mary’s and afterward at Annapolis, the County courts having but limited jurisdiction, and that chiefly criminal. In 1796, at the time of the incorporation of the city, there was the Chancellor’s court, at Annapolis; the General Court, Chief Justice, and three judges; the Court of Appeals, two judges: the District Court, Chief Justice, and three associates. District courts set alternatively at Easton and Baltimore four times a year: circuit courts were held at Easton and Annapolis alternatively twice a year, or plans court set on the second Tuesday of every month. Justice was sharp and severe, however, the punishments cruel. Hanging, gibbetting, whipping, the pillory, the stocks and the wheelbarrow were the common penalties. There was no penitentiary then, so convicts were sentenced to the chain gang and forced to work on the public roads. In 1758, at the time of the Baltimore County Sheriffalty of Daniel Chamber, the only jail possessed by Baltimore town was a ram sack longer structure on the east side of S. Frederick St. In the days of the Harbaugh and the old courthouse, the jail, the solid structure, stood on the corner of Lexington and St. Paul streets, where the record office now is. The Baltimore County jail, on the site of the present city jail, was built and finished in 1802 from designs by Robert Carey Long.

THE BEGINNING OF CITY GOVERNMENT

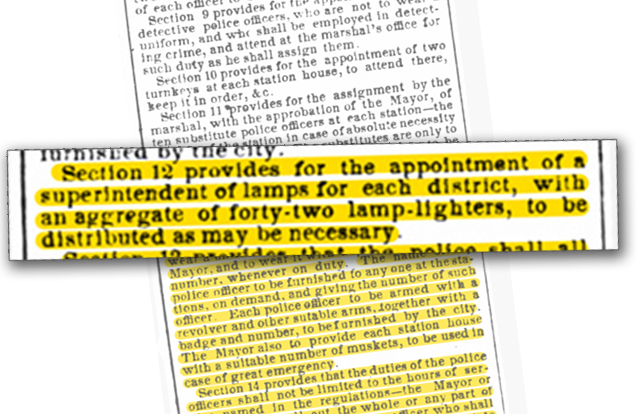

Government by the legislature through boards of commissioners is to slow a process to suit large cities. It besides creates too many ear responsibilities. A legislature has no time to govern a state and a city at the same time – to regulate general affairs and details at once. The general assembly of the state from 1774 to 1796 had to make no end of municipal regulations for Baltimore town: to regulate the gaging of casks, the paving of the streets, the placing and lighting of lamps, the appointing of port wardens, the cleaning of the basin, the ordering of the Night watch, the conduct of the markets, &c. At last the legislature got as tired of this as did the petitioning of people of Baltimore, and the “act to erect Baltimore town, in Baltimore County, into the city, and to incorporate the inhabitants thereof,” was passed in November session 1796, the act of specifying that “the good order, health, peace and safety of large cities and towns cannot be preserved, nor the evils and accounts to which they are exposed avoided or remodeled, was out the internal power, competent to establish a police and regulations fitted to their particular circumstances.” The charter and its subsequent amendments comprise the Constitution of Baltimore. The city was to have a seal, to be divided into wards, (8 at first,) to have a Council of two branches, (the first branch to be elected Viva Voce by voters worth not less than $1000;) the voters at the time of voting for members of the first branch were to vote for one at lector in each Ward, and these were to meet and choose the mayor and members of the second branch. The Corporation was given the power to enact all laws and ordinances necessary to preserve the health of the city, to remove nuisances, have the streets lighted and patrolled, care for docks, basin, harbor, and river, license auctions; &C., &C., Levy taxes, collect fines, &c.

James Calhoun was elected first Mayor of Baltimore, and among the names of electors and Councilman who were chosen, we find such prominent citizens as George Reinocker, doctor. George Buchanan, Samuel Owings, Zebul Hollingsworth, Jesse Hollingsworth, David McMachen, Hercules Courtney, Jeremiah Yellott, Adam Fonerden, Philip Rogers, James A. Buchanan, Peter Frick, Englehardt Yeiser, Joseph Biays, Nicholas Rogers, John Merryman, Robert Gilmor, Edward Johnson, Job Smith, Daltzer Shaeffer, & co.. It will be noted Hal the Pennsylvania German and’s got Irish names loom up on this list, alongside the good old English names, however, and those of Huguenots. James Calhoun himself was of Scotch Irish stock, coming into the province about 1771. He made himself prominent on the patriot side during the revolution and was on several of the most active committees. At the date of Mr. Calhoun’s election to the honorable place of first Mayor of Baltimore he was president of the Chesapeake insurance company, and lived “cross North Lane, 1 E St.,” that is to say, on Fayette Street, south side, one door west of North Street, his office being on the corner.