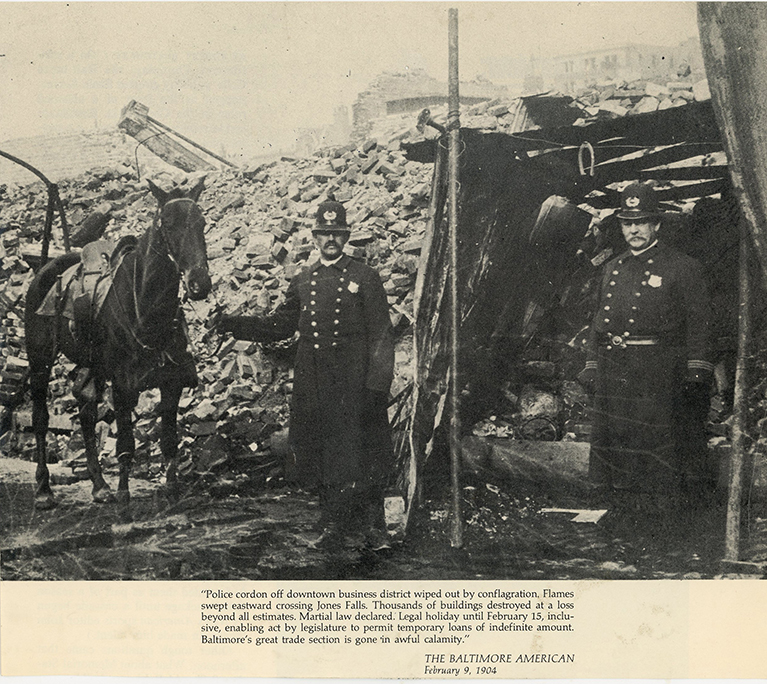

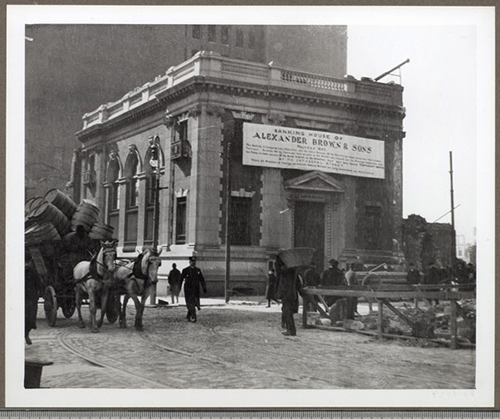

Baltimore Fire 1904

The Great Baltimore Fire of 1904

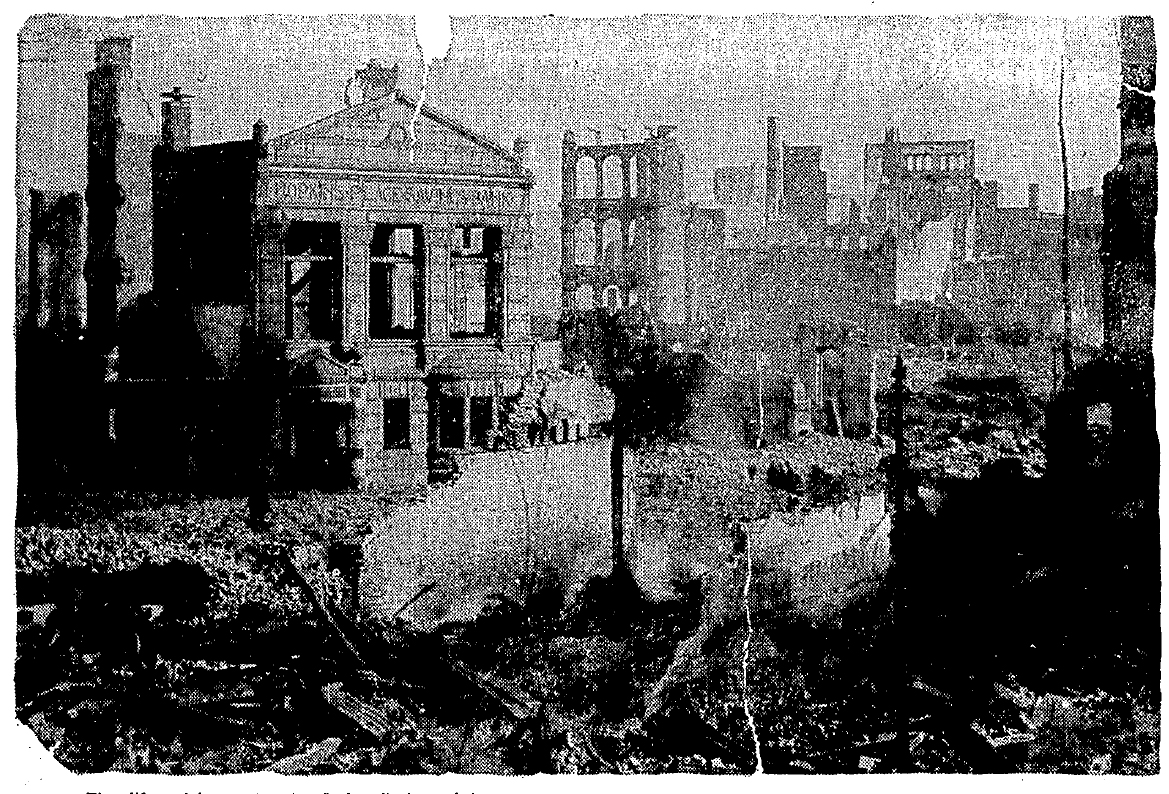

Baltimore In Ruins After The Great Fire Of 1904

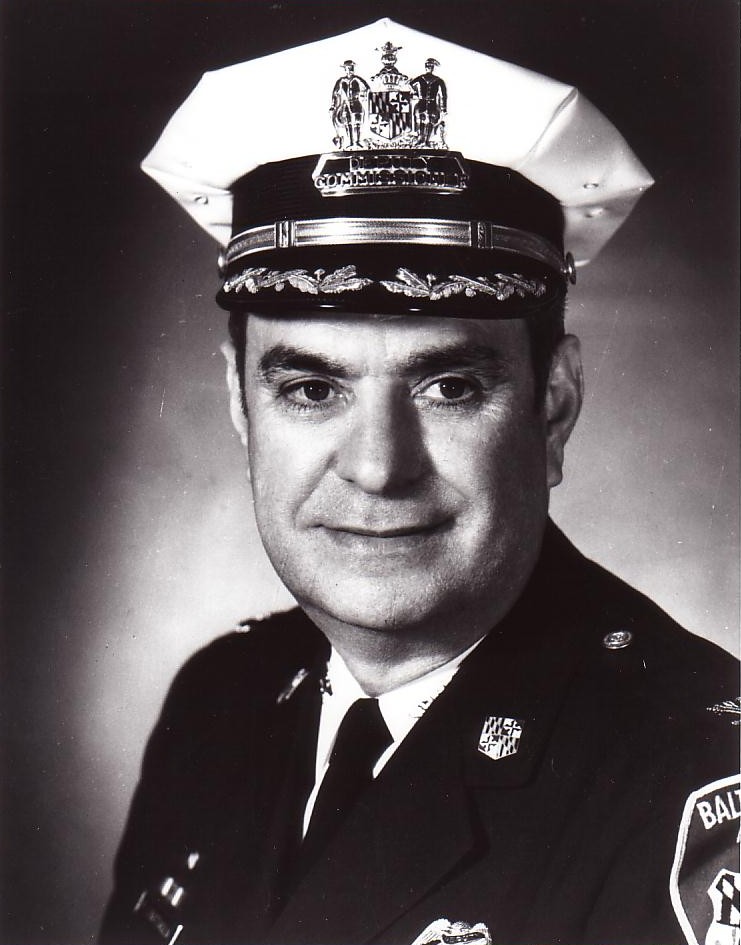

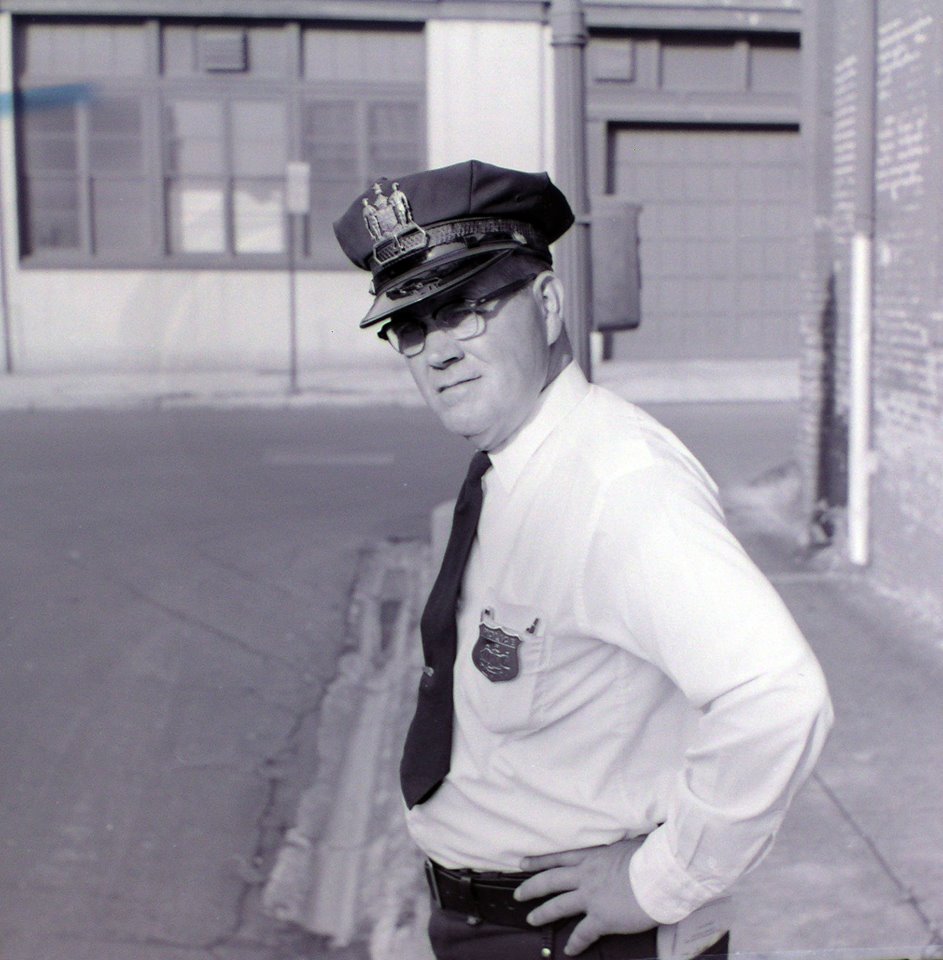

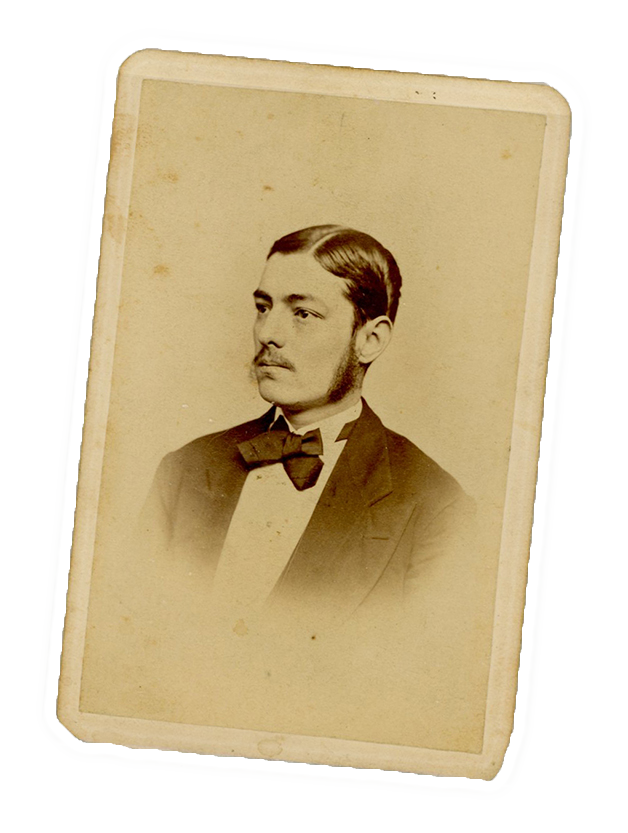

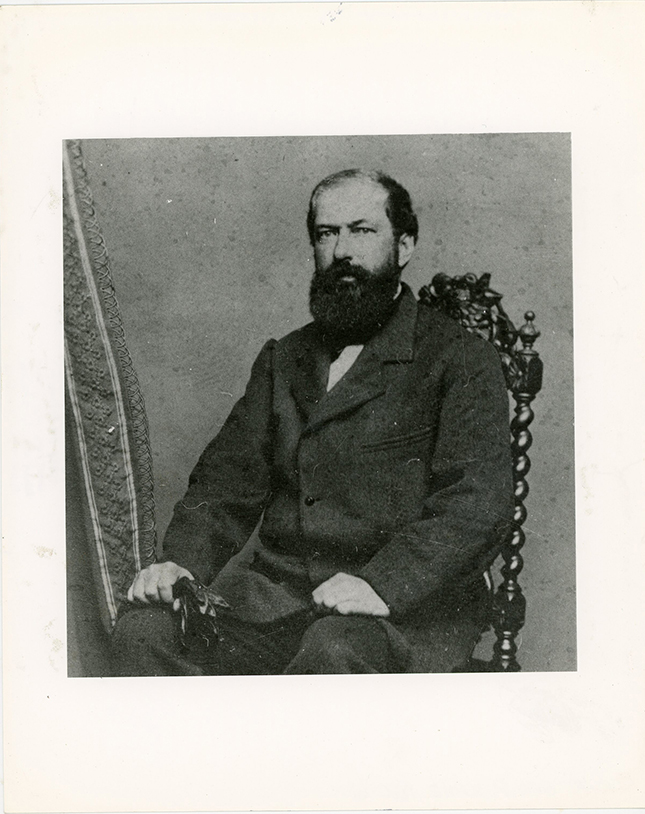

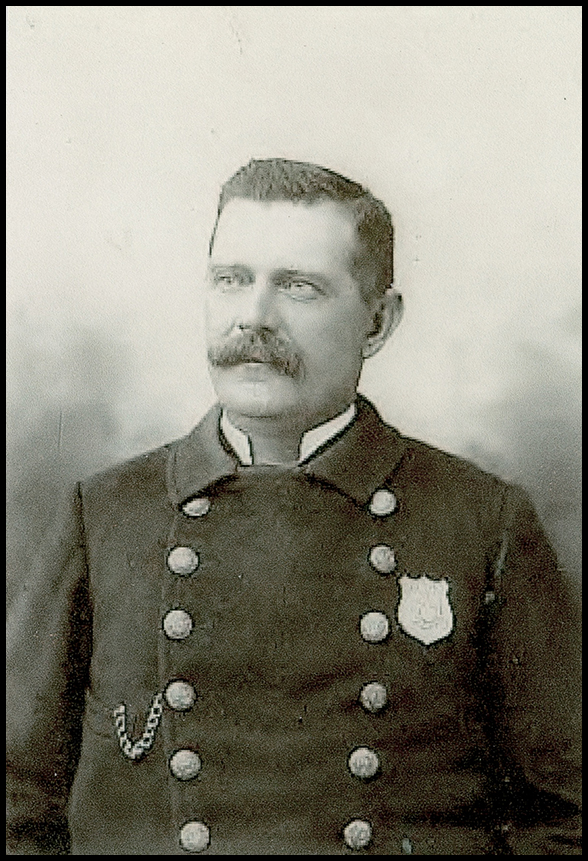

WILBUR F COYLE

The Sun (1837-1987); Feb 29, 1920; - pg. A6

One black night from the home of City Hall I saw Baltimore burn. I will never forget that site. Few people have ever been privileged to look down upon the populous city and watch as his very heart was eaten. It was a terrible hollering experience – to look. Look. Look. And know that there was no force to stay the flames: the thousands of human beings must stand important and hopeless while myriads of hot, red tongues withered everything in their path.

It was as a memorable night of 7 February 1904 – the night of black despair – to which I refer: when Baltimore was swept by a conflagration almost an equal in the history of American cities: when modern building after modern building, heretofore assumed to be fireproof succumbed that with amazing rapidity. Fireproof – amiss – the term refers to something that does not exist. I saw Baltimore burn: I know. Yes, 7 February 1904 was a terrible day followed by a more terrible night. The city was stunned and thousands of individuals common exhausted by fruitless efforts to rescue their goods and merchandise had abandoned hope.

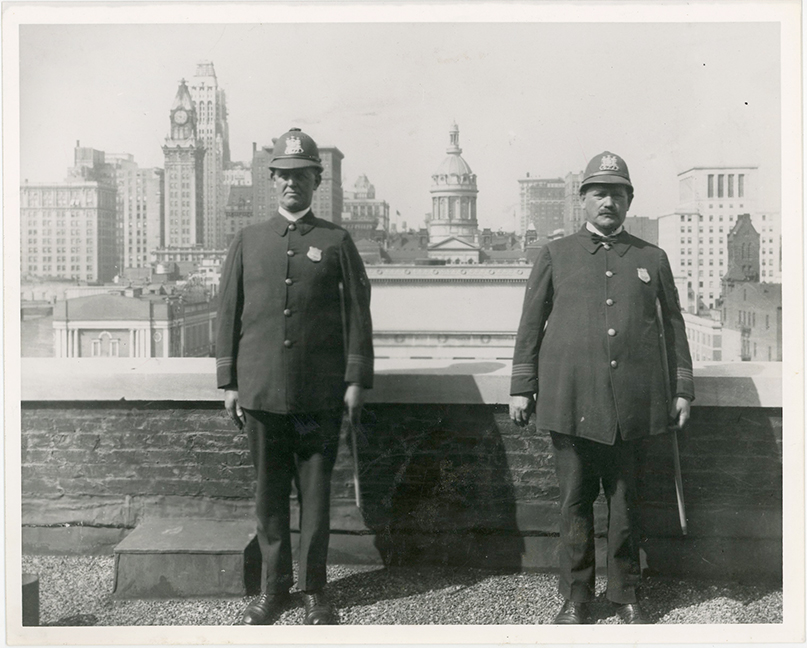

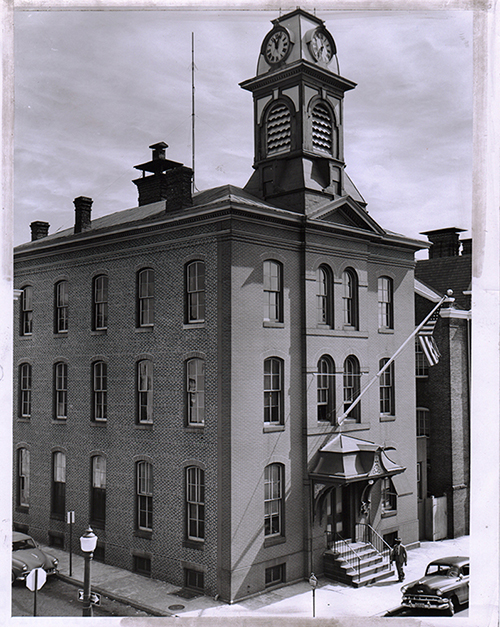

Late last night, utterly fatigued. I was at the city library, City Hall. Suddenly I remembered that hanging upon a book almost within reach was the key to the dome. I was tired – “deadbeat” – but I realized that never again with an opportunity be presented to see such a spectacle. What time it was I do not know. Because I did not know then. I took no note of time in its flight. With the key of the dome, I went from the third to the fourth floor where, in the West car door, is a door which bars the way to the dome. Just then I encountered two men from York Pennsylvania who had, on a special train that brought the fire apparatus of that city to our city I invited those strangers to go along. The little door blocking our path responded readily and we began to gradually ascent through the narrow, black Connell was laying its semicircular courts through walls of solid Masonry just where the dome shows above the roof that covers the winds of the City Hall.

The passage was [in fact is] so contracted that we had to go single file and with great caution. As we slowly rounded the curvature of approaching the point of exit above we notice through the narrow aperture the reflection of the flames. It seemed almost that the City Hall itself was on fire. This strange uncanny staircase, which upon that particular night had all the unpleasant tree suggested of a dungeon. It was connecting to a link between the lower region and a large circular mid dome apartment into which we emerged. This is, in reality, a great barrel 50 or more feet from its stone floor to the ceiling. The view in all directions is unobstructed through immense oblong windows extending almost from top to bottom facilitating and unhampered observation.

The passage was [in fact is] so contracted that we had to go single file and with great caution. As we slowly rounded the curvature of approaching the point of exit above we notice through the narrow aperture the reflection of the flames. It seemed almost that the City Hall itself was on fire. This strange uncanny staircase, which upon that particular night had all the unpleasant tree suggested of a dungeon. It was connecting to a link between the lower region and a large circular mid dome apartment into which we emerged. This is, in reality, a great barrel 50 or more feet from its stone floor to the ceiling. The view in all directions is unobstructed through immense oblong windows extending almost from top to bottom facilitating and unhampered observation.

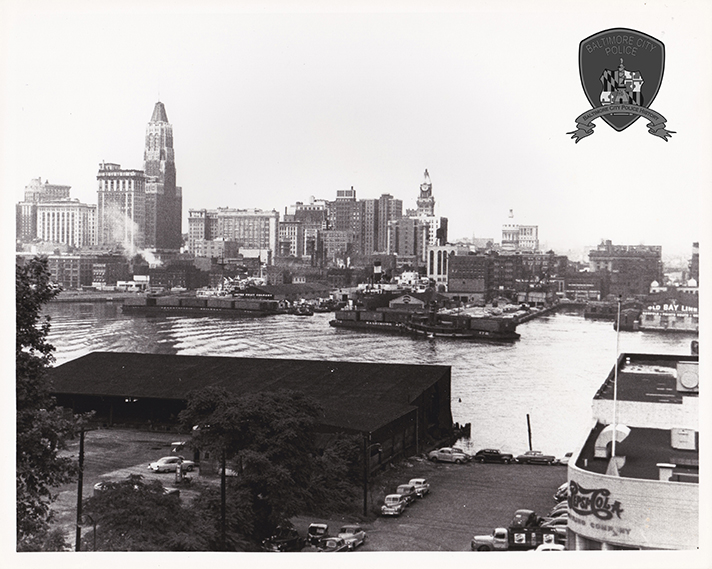

The view from the dome from the Crystal room – it may be sowed designated because of the number of character of its window – there extends a long spiral staircase which brings the traveler to the section of the dome where the clock in the apparatus that run it are installed. I had intended to climb those precipitous stairs and keep going, but I did not do so. The spectacles to those long windows of the Crystal room were almost paralyzing in its effect. One’s power of a locomotion’s seemed affected. I was utterly tired. I wanted to CARL up. To have gone higher one of added nothing to the view. It was all laid out before me – splendid old Baltimore was ablaze. It seemed to that the lower part of the city had caught fire, so near had the flames crept, and the sweeping glance to the south showed that the entire section between the building and the waterfront was read. Great columns of fire viciously stabbed at the darkness; flames passed from building to building, from block to block. Leaving nothing but blazing the breeze, gaunt gutted buildings, and desolation in the wake.

Mere words can convey no adequate idea of the terrible scene: any description must fail. It was maddening to realize that dear old Baltimore was burning like tender and that no human power could render effectual aid. This strange room was for the time being sheltered me from the dense smoke and flying embers that fitful dust sent over the dome was itself brilliantly illuminated spasmodically. The effect of the fire was startling. Flash after flash being accomplished by dull “boom” of explosions, which concussions mingled with countless other unwanted disturbances incident to the fire.

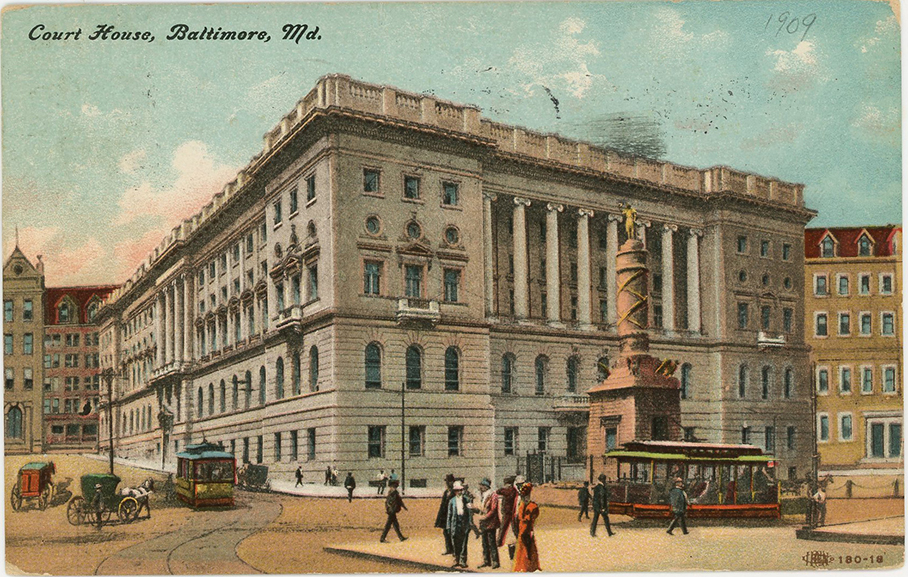

I really do not think the extent of Baltimore’s catastrophe is now appreciated. As I watched that night as flames ate their way through its heart I did not  see how the city could ever recover. Think of the vastness of the destruction: from liberty Street on the west, Jones falls on the East, Charles and Lexington streets on the north, with all the buildings on the south side of Lexington Street to St. Paul Street, either going or gone, and a great battle staged on St. Paul Street to save the courthouse. Which was next in the past of the destroyer – that was the appalling situation 17 February 1904. It is beyond the imagination to picture 140 acres of a compact city like Baltimore burning or wrecked. It was terrifying to realize that there was practically no limit to which the fire fiend. Now on harnessed, might you go, it seemed as a look down upon it that the fire would take it’s course to the whole of East Baltimore contagious to the waterfront and burn, burn, burn until open country was reached. And so I am convinced it would. Had not it’s course been stayed by that filthy stream, the Jones Falls.

see how the city could ever recover. Think of the vastness of the destruction: from liberty Street on the west, Jones falls on the East, Charles and Lexington streets on the north, with all the buildings on the south side of Lexington Street to St. Paul Street, either going or gone, and a great battle staged on St. Paul Street to save the courthouse. Which was next in the past of the destroyer – that was the appalling situation 17 February 1904. It is beyond the imagination to picture 140 acres of a compact city like Baltimore burning or wrecked. It was terrifying to realize that there was practically no limit to which the fire fiend. Now on harnessed, might you go, it seemed as a look down upon it that the fire would take it’s course to the whole of East Baltimore contagious to the waterfront and burn, burn, burn until open country was reached. And so I am convinced it would. Had not it’s course been stayed by that filthy stream, the Jones Falls.

A grand total of 1526 buildings, many modern, its preparation of skyscrapers and in addition for lumber yards where the fuel for that disastrous combustion. Truly an appalling panorama it was as viewed by the all struck watchers away up in the dome of the City Hall. Acres blazing or in ruin, and no relief in sight how long I was in the dome I have no means of estimating. But suddenly I heard faint shouts. Which noises I knew could come only through the narrow channel of which I had climbed. I knew, too, the call was a warning, although I really felt there was no immediate danger, I lost no time in retreating through the tunnel and was soon back on the corridor on the fourth floor. It developed that a watchman, no doubt making his rounds, found the door of the dome open and, suspecting that someone was up there, had reported the discovery to the custody and of the building. The latter wisely decided to make an investigation, and as the searchers ascended it was there shouting which I heard and answered.

At that moment the City Hall was in no danger, but it wasn’t long before the doom seemed sealed. Only those who were in the building that night realized a close call it had. True, to the westward, whence the fire earlier came, the hall was then protected by the courthouse in St. Paul Street side of which was damaged and also by the granite post office the stone structures acted as a screen for the municipal building and both would have succumbed before the City Hall was attacked from the West. The threatened assault, however, did not come from that direction at all but from the southeast. I cannot recall the variations of the wind that fiery night nor the phenomenon that occurred. But it is a fact that the flames had swept from west to east and seeming well beyond that City Hall zone, slowly worked back from the South was southeast. Coming steadily toward the big structure this was the situation when I returned from my venture into the dome.

The flames approach. From the first branch Council chamber member a good view of the approach and fire would be obtained and when I went there I found the number of persons assembled. The fine chamber of commerce building a few blocks away to the southeast was ablaze midst a score of others insight and the destroyer were beating back with seeing a deliberate purpose of getting the smaller structures along Fayette Street, opposite the exposed southern when of the City Hall. It wasn’t long before all the buildings across narrow Fayette Street were ablaze and all but one, the Giddings bank building at the southeast corner of Fayette and Guilford Avenue, were utterly burned, correct, collapsed. Through the balance of the night, a determined flight was put up to save this antiquated bank and strange to say this effort was successful. With blazing structures across the street, it seemed for a period that the City Hall must certainly catch. The heavy window glass was hot and with myriads of sparks in the air seeking lodgment in the edifice, there seems little chance of escape.

The flames approach. From the first branch Council chamber member a good view of the approach and fire would be obtained and when I went there I found the number of persons assembled. The fine chamber of commerce building a few blocks away to the southeast was ablaze midst a score of others insight and the destroyer were beating back with seeing a deliberate purpose of getting the smaller structures along Fayette Street, opposite the exposed southern when of the City Hall. It wasn’t long before all the buildings across narrow Fayette Street were ablaze and all but one, the Giddings bank building at the southeast corner of Fayette and Guilford Avenue, were utterly burned, correct, collapsed. Through the balance of the night, a determined flight was put up to save this antiquated bank and strange to say this effort was successful. With blazing structures across the street, it seemed for a period that the City Hall must certainly catch. The heavy window glass was hot and with myriads of sparks in the air seeking lodgment in the edifice, there seems little chance of escape.

The catastrophe was so widespread and appalling that the senses were actually deadened or numb and a building more or less did not seem of great Monument. I glanced about the sumptuous chamber luxurious in his heavy draperies, it’s walnut furnishings and costly carpets and I wondered whether the moment had come to put into execution a plan I had to save the most valuable objects insight – the portraits of the mayors of Baltimore. Although many of these paintings have since been removed and distributed throughout City Hall, a score or more at present hangings in the mayor’s sweet, they were at the time of the fire all in the two chambers of the Council. The great wall space in each branch was covered, the rooms, in fact, were a portrait Gallery of consequence, containing as they did effigies of the mayors from James Calhoun 1797 to Thomas G. Hayes 1903. There were other fine paintings in the group, particularly of the men – including Gen. Samuel Smith – who took part in the defense of Baltimore in 1814. Such artists as Charles Wilson Peale, Rembrandt Peale, Thomas Sully and others of a lesser population were represented. The campuses, some of which were very large and heavily framed, or of great intrinsic value and historically and sentimentally priceless.

Earlier in the night [or day for it may have been daylight] I had labored to get all the records in my custody out of City Hall when it seemed to the building was directly in the path of the fire and it was almost a personal disaster to have to abandon the portraits of those fine men who had in a sense, then the builders of Baltimore. I determined these paintings should not be abandoned. I would cut them from their frames!

This I could do quickly. For I had a trusty knife ready, and with the assistance of the others present it would not be a difficult job, I could roll the campuses up and escape with them under my arm – but when should I cut?

That was, in reality, a burning question. From the other side of Fayette St., South to the waterfront, the city was ablaze. The City Hall would be next. Nothing was now between it and the fire. Was a time to strike? I waited: I waited. The structures across the street were gone. Somehow the blistering heat did not burst the heavy window glass and ignite the hall. The showers of sparks passed harmlessly by. The miracle had been wrought. Daybreak with the terrifying spectacle it revealed was at hand. The little party in the Council chamber broke up. Such was the culminating incidents of the night spent in the City Hall while ruin reigned without. A night that followed a day into which had been crowded, and the experience of the average individual, gloom, dismay, fear amounting almost to terror.

In The First Hours

early in the day [7 February 1904] it was noised all over town that a great fire was spreading to unwanted proportions involving a considerable area, but no one dreamed of the impending danger. I went downtown in the early afternoon and called at a newspaper office to obtain information concerning the conflagration. I was asked by the editor to procure a plat of the S. Library St. section where the fire was raging, the purpose being to reproduce the chart immediately in connection with the story of the conflagration. I went to the City Hall to get a map and brought forth a large atlas containing, among other charts, the plat requested. Some persons on the sidewalk seeing me emerged from the hall was a mammoth atlas set up a shell and twitted me, assuming I was taking the record to a place of safety because of the fire than half a mile or so distant. Those looters must later have credited me with supernatural wisdom or discernment. Only a few hours elapsed where not only myself but other city officials were nervously hurrying wagon loads of records from the City Hall. I did not let my atlas get out of sight and before it could be used the newspaper office was in flames. By that time the volume was back in city halls library. I saw to that personally.

Meeting the Records

Sometime later when the big Continental building at the corner of Baltimore and Calvert Street became luminous: flames streaming from every window. I thought the City Hall and post office doomed. So and others. There would be no further delay; we must move. I had engaged some teams [so I thought] to meet the emergency but who could hold conveyances under such conditions? People with frantic and offering fabulous sums to have their goods moved, in front of almost every establishment along Baltimore, Lombard, South, Calvert, and scores of Streets wagons parts and rays were backed up, loaded in hustle Austin to drive away and deposit their burdens in another building which surely fell prey to the flames. This, unfortunately, was the experience of very many.

There were few officials at the City Hall that memorable Sunday. Mayor Robert M. McLean, clad in a fireman’s outfit, was one the fire line of the superintendent of buildings and his force was on St. Paul Street assisting in saving the Zen new courthouse. But I recall three persons I met momentarily at the hall – Mr. William A. Larkins then deputy Commissioner of Street cleaning: deputy city collector Hartman, now judge of the Appeal Tax Court, and Mr. Frank J Murphy, clerk of the same court. To Mr. Larkins and Mr. Murphy, I feel I owe a debt of gratitude. The form of voluntarily sent me a detail from history cleaning forces to assist in removing invaluable records from the city library, and Mr. Murphy suggested that I share it struck he had managed to commandeer, which with the one I seized enabled me to clear the city library of many official Street opening plats, books and other records, the loss of which would have been irreparable.

Danger to the Library

Quite a. A force of men was carrying out these archives. The drivers were instructed not to unload the wagons under any conditions. I think the records were sent to Union Station. At all events, they were taken to the place of safety and returned immediately after the fire. Though several times were taking out this did not make a great impression on the whole equipment. Many, many books were left in the cases, but the rarest of the collection was sent away. And I loaded myself down was my arms, including first records of Baltimore town in Jonestown: the first directory of Baltimore town and fell’s point and such. As a final choice, I would have turned the crowd on the streets into the library rather than see the books destroyed, on the chance of getting some back again. Many merchants did this in an effort to salvage their stock.

While stirring around the city all I ran into Mr. Hartman, deputy collector. We passed each other in a rush, but I reminded him that in a large attic room where the accumulated tax records of over a century which were doomed if the building caught. It was the work of days under ordinary conditions to remove these. And Mr. Hartman said the books would have to be abandoned. He was desperately intent upon getting the “live” records of his department out of harm’s way since these showed what money was due to the city from taxpayers of the volumes meant not only chaos and irreparable confusion but the loss of the municipality of millions of dollars.

All the strenuous physical effort. Mental strain and sustained excitement was very exhausting, and having done my utmost in the circumstances to protect the city property and records in my custody I went back to the city library. Where the key to the dome suggested a trip, heretofore described, to that point.

I remain downtown in the fire zone, or at my office until 6 o’clock that evening – Monday. 8 February 1904, I was as black as a minor when I got home and so tired I seemed in a trance – yet I was but one of many thousands in the same flight. Some were half-crazed by their losses, demoralization and disorganization were complete. Everyone had been laboring under intense excitement, accompanied by a depressing sense of irreparable loss. The city was shocked beyond measure. As I write all this seems an occurrence of yesterday rather than of 1904. It is almost impossible to conceive that a new generation has risen which has no personal knowledge of that moment this occurrence. Oft has the statement been made that Baltimore is better as a result of that fire. I made it myself, and it is true – but I always make a mental or rather sentimental reservation. It did make possible the building of a splendid system of municipal docs; it did give the opportunity to widen streets, and there is no question that in many physical respects this city has splendidly advanced. It, too, wake the people and they have since been more alive to their opportunities. The spirit of broad is an evidence of this – yet even to this day, it makes me sick to think how building after building, landmark after landmark went up in a flash of flame and a puff of smoke.

As to chance – well possibly it is necessary to make all Baltimore look like new; to get away from the original surveys; to turn Cal paths into boulevards, to revamp, rebuild and beautify from time to time but how much of the old city individuality, or personality was destroyed in the process?

Is it better than Baltimore look new and bright and smart and modern and right up to the minute – rather than an orderly, enterprising, populous city with a dash of quaintness, and suggestions of historical associations in its buildings and streets? Has a city like Boston lost anything by adhering to its old areas to early surveys, and accentuating, rather than destroying and obscuring evidence of its antiquity? Well, well, I’m getting over my head now, – let’s get back to the fire, for a brief period.

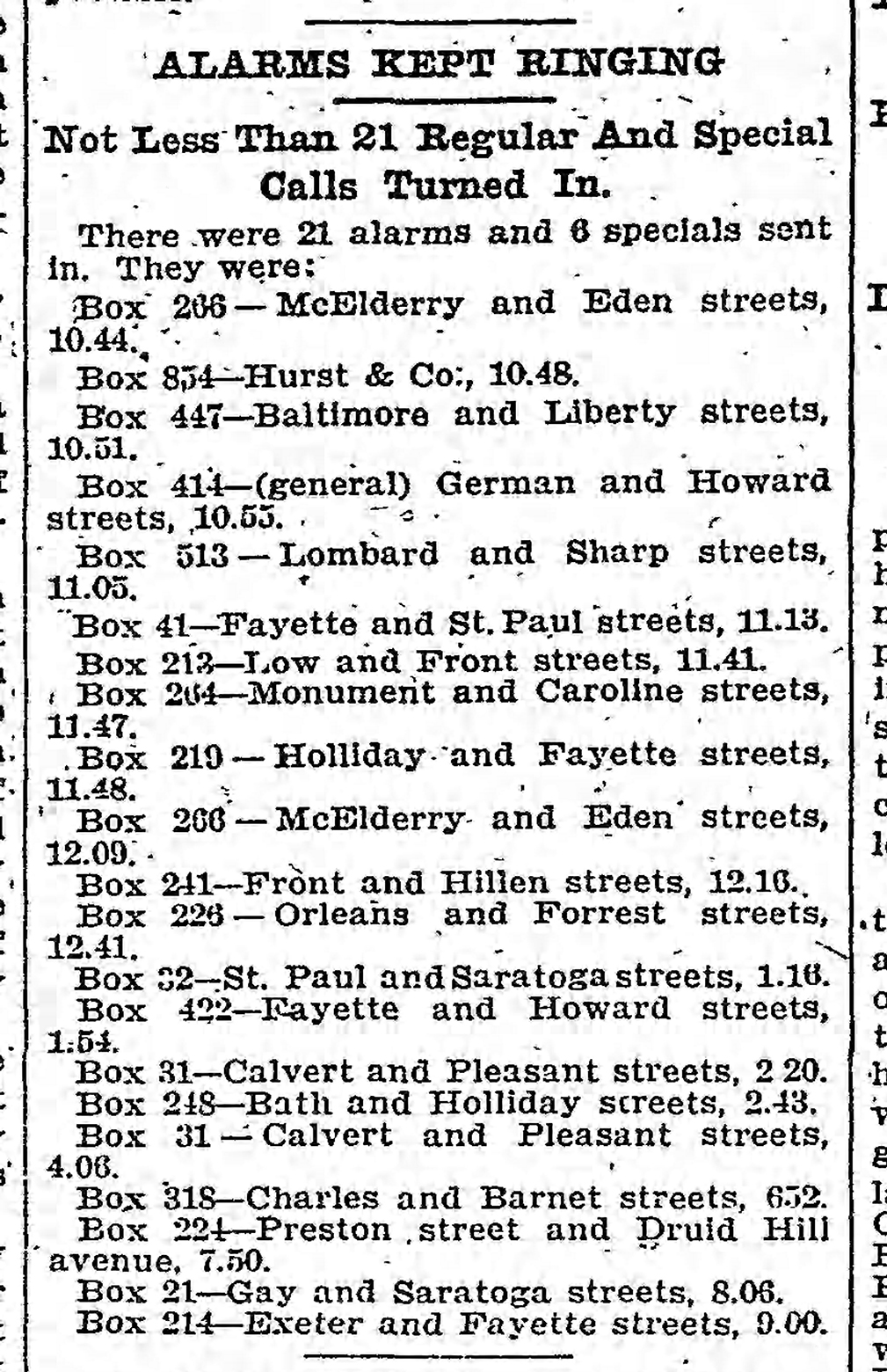

This started at 1048 [the time registered by thermostat alarm] in the six-story brick building occupied by the J. E. Hurst company, wholesale dry goods and notion house, and German [Redwood] and liberty streets and Hopkins place. In his report Chief Engineer Horton said, “The fire raged until 11:30 AM Monday, 8 February 1904” but this does not mean necessarily it was then extinguished. As a matter of fact, it to load and burned brightly along the eastern extremity of the area until much later, an estimated 36 hours and all. There is no way of accurately computing the loss, but $125 million is the generally accepted estimate, taking all elements in the consideration. This figure is, however, more or less arbitrarily set.

No one was killed during the fire, though some firemen sustained injuries, and there were wild rumors of many fatalities. Mayor MacLean refused all outside financial aid and he announced to the world that Baltimore would rebuild through his own efforts, which it did was amazing rapidity. Several cities, however, rendered valuable assistance at the fire – apparatus, and fighters being rushed there from several points. Written 29 February 1920 as described by the city librarian Wilbur F. Coyle – The City Librarian, describes the destruction of Baltimore by fire, 16 years ago this month February 29, 1920, as seen in the City Hall dome – the removal of the records – the plan to cut valuable portraits of mayors from their frames to save them from the flames. These are the personal Chronicles of one who from City Hall Saul Baltimore burning

A COUNTRY OF GREAT FIRES

Some of the Blazes That Have Cost Millions of Money and Many Lives

The United States has, it is said, a record of destruction by fire not equaled by any other country. The greatest, of course, was "The Great Fire," which swept Chicago in 1871, burning over 2,124 acres, nearly covered by buildings, causing the loss of a great many lives and a property loss of more than $100,000,000.

The Greatest Fires Baltimore had ever known up to this time were the Clay street fire of July 25, 1875, and the Hopkins Place fire of Sunday, September 2, 1888, both of which are described elsewhere. Big fires in other parts of the country have been as follows:

Savannah, Ga., in 1820, 463 buildings and $4,000,000 value destroyed.

New York, in 1835, 530 buildings, 52 acres burned over, and $i5,000,000 of property destroyed; In 1845, 300 acres burned over, $7,500,000 value, 35 lives lost.

Charlestown, Mass., in 1838, 1,158 buildings.

Pittsburg, in 1845, 100 buildings; $1,000,000 property value.

St. Louis, in 1849, 15 buildings; $3,000,000 value; in 1851, 2,500 buildings destroyed. Philadelphia 1850, 400 buildings.

San Francisco 1831, 2,500 .building’s and a number of lives lost; property -value, $10,000,000.

Portland Maine, in 1866, over one-half the city 200 acres burned over and 1,743 buildings destroyed.

Boston; in 1872, 65 acres or mercantile section burned, including 776 buildings, nearly all of brick and stone construction; property value, $75,000,000.

In June 1889, Seattle, Wash., was destroyed, the loss being $30,000,000. Two months later Spokane- Falls burned. The loss being-$7;000,000.

At Lynn, Mass., In November of the same year $5,000,000 worth of property was consumed. Within a few days, the fire broke out in the dry goods· district of Boston and property valued at $6.000,000 was burned.

In October 1892, a fire at Milwaukee caused a loss of $6,000,000,

At Hoboken on June 30, 1900, the North German Lloyd. Piers and steamships sustained a loss of 10,000,000 and 200 lives were lost.

At Jacksonville, Fla., May 3, 1901, loss estimated at $12,000,000 and 1,300 houses were burned some lives were lost, but the number was not exactly known. . .

October 25, 1901, · In Philadelphia, 19 persons were killed and about $500,000 damage was done by a fire in Hunt, Wilkinson & Co.'s furniture warehouse, on Market street, near Wanamaker's Store.

At Waterbury, Conn., February 2 and 3 1904, Damage now estimated· at $2,500,000 was done.

New York; March 17, 1889, The Windsor Hotel fire, in which 45 persons lost their lives and a property loss of about ·$1,000,000 caused.

7 Feb 1979

The Great Baltimore Fire of 1904:

Isaac Rehert

The Sun (1837-1987); Feb 7, 1979;

pg. B1

7 February 1979 marked the 75th anniversary of the worst disaster ever to strike the city of Baltimore known as “the great Baltimore fire” what follows are two recollections of that fire

The Great Baltimore Fire of 1904:

Two Neighborhood ‘Girls’ Remember

By Isaac Rehert

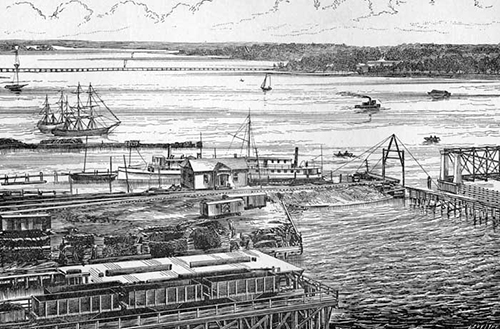

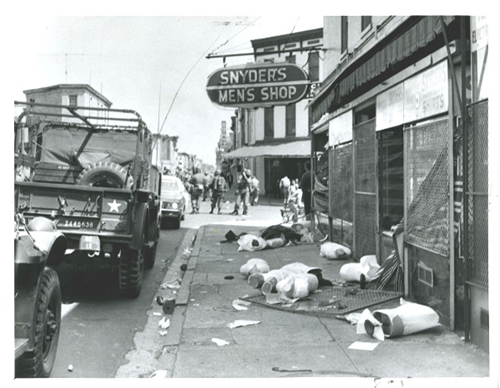

It began at Hopkins place and German (now Redwood) streets, in the warehouse of the J. Hurst Company; from there it quickly spread to surrounding buildings.

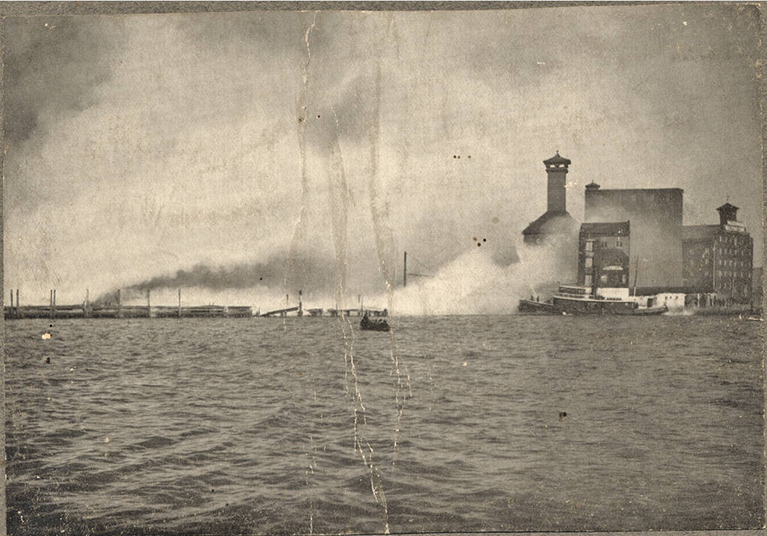

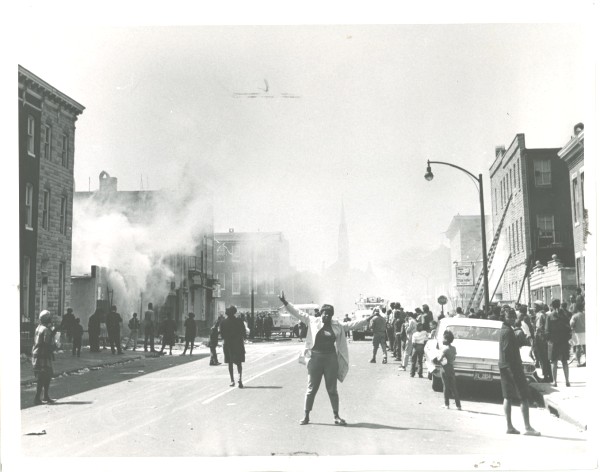

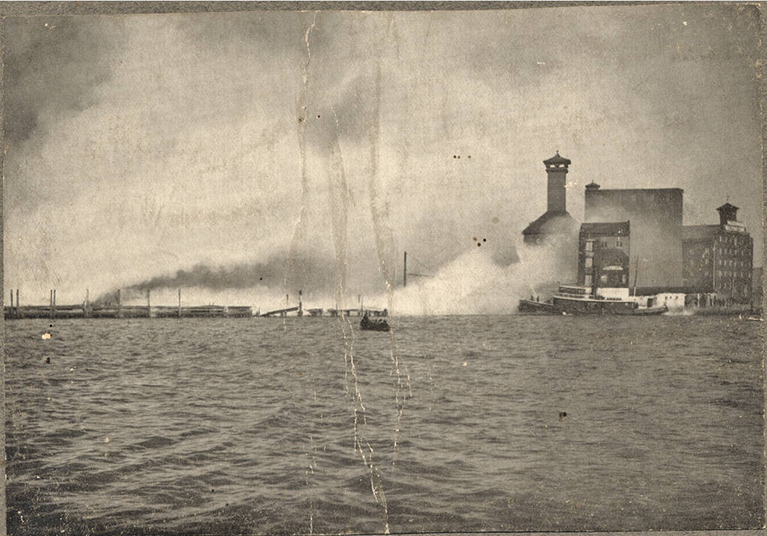

For 2 ½ days, it raged, eating its way eastward in a roaring, hissing sheet of red flames across the half-mile front reaching from Fayette Street to the harbor.

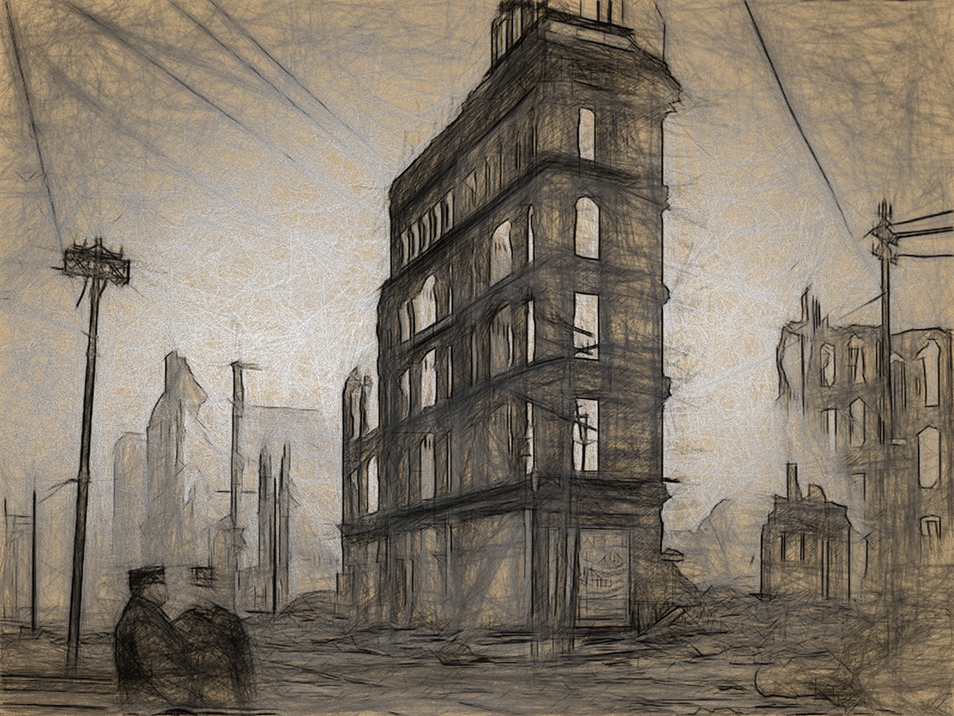

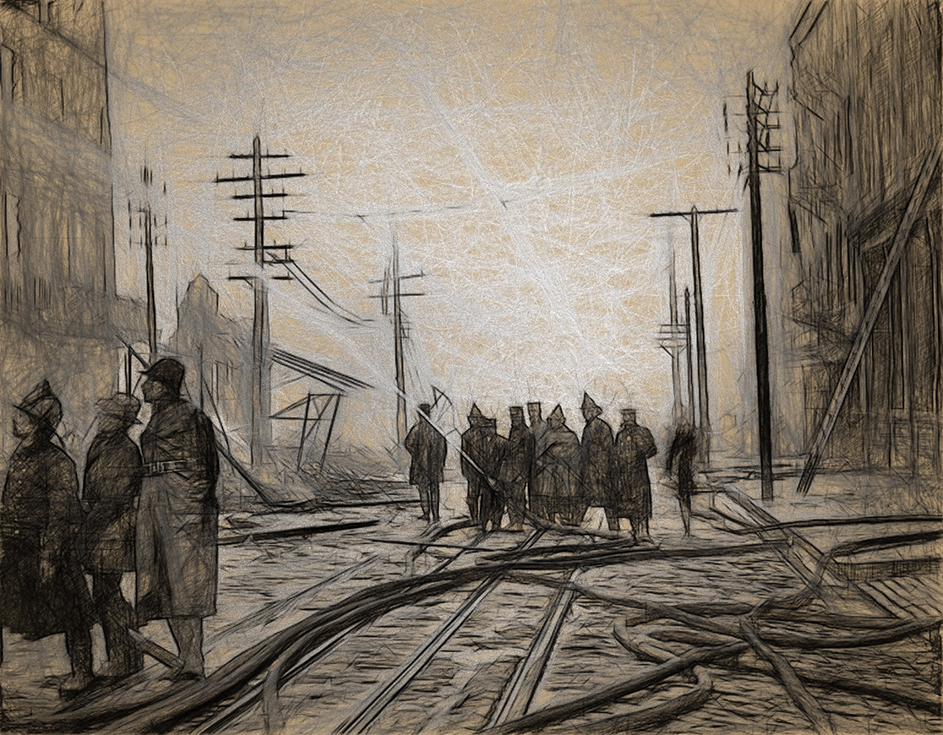

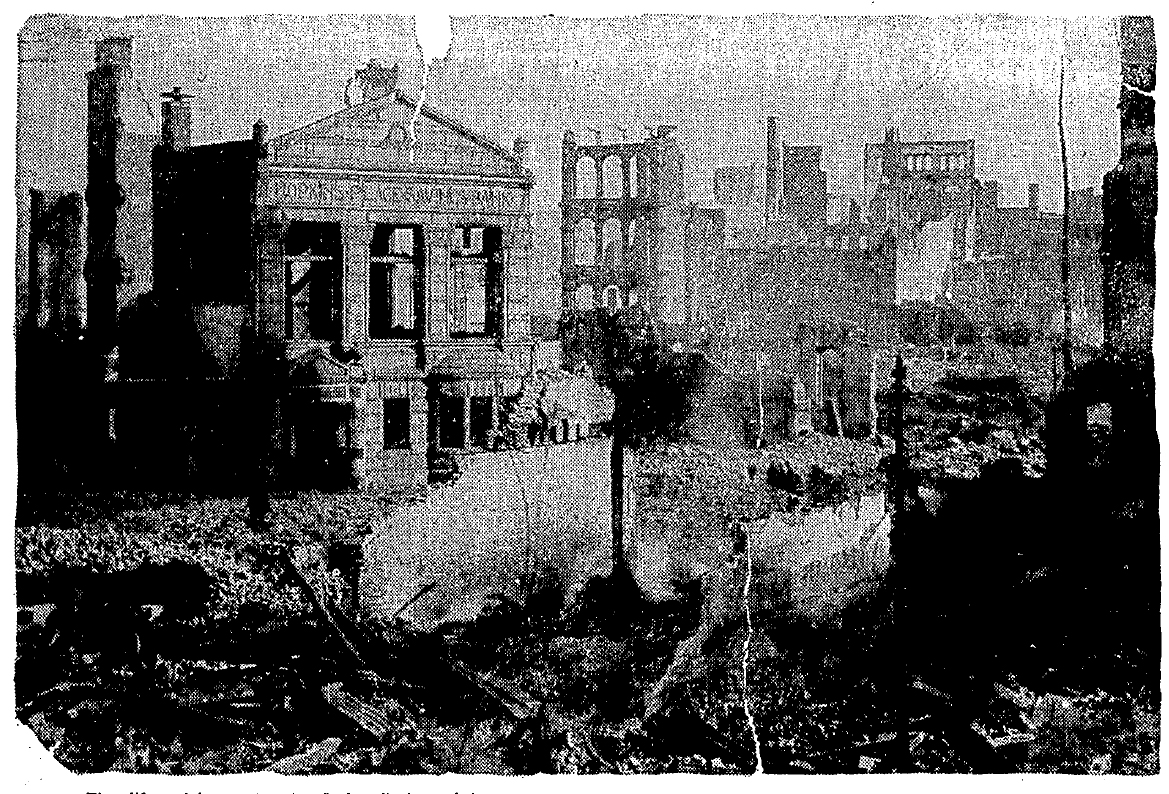

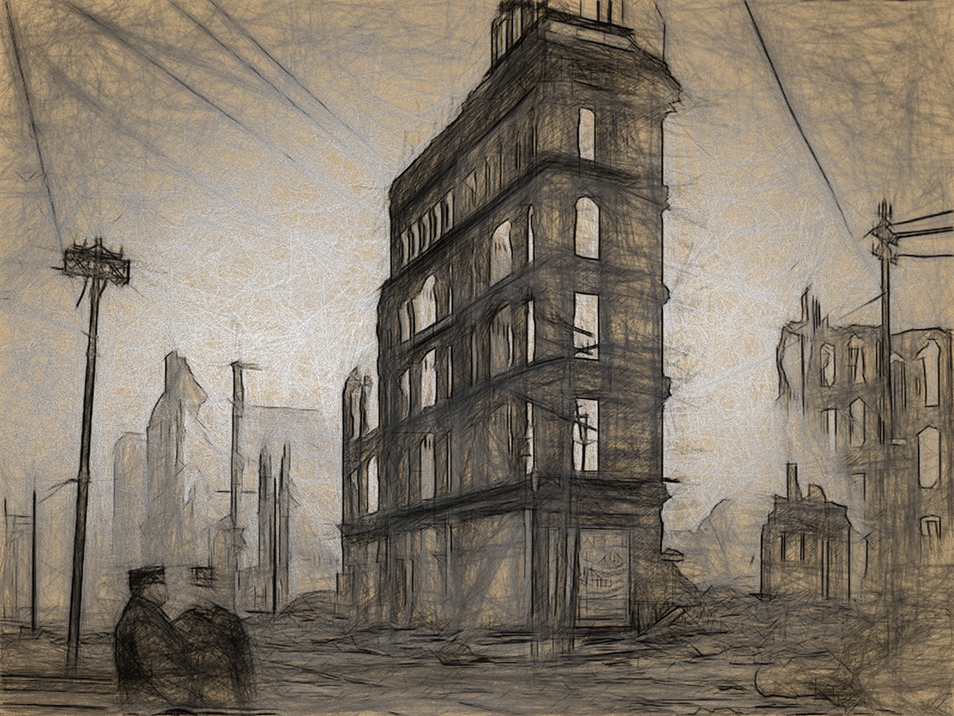

Before it was contained at the Jones falls, it has consumed an area of more than 140 acres, destroying 1500 prime office and manufacturing buildings, leaving Baltimore’s entire business district a graveyard of smoking black embers.

Financial losses were estimated at between 100 million and $150 million.

Two little girls living in Baltimore during those faithful days – both now in their 80s – still recall the fear, the danger and excitement of those few days, when the destruction of the whole city seemed imminent.

One of them, Rosa Kohler Eichelberger, has written a book about it for children and young adults called “big fire in Baltimore,” just published by Steiner house a local firm.

The other, Esther Wilner Hillman, in an interview, has related a little-known facet of that stirring piece of Baltimore history.

Rosa Kohler Eichelberger

“It was a bitter cold Sunday morning, about 10 or 11 O’clock, with first got her attention where the fire engines, shrieking by every minute, with their sirens and their bells. We knew there had to be a big fire somewhere.

“We were living at 329 North Carrollton Ave. – one of those three-story houses with little white steeps. It was a beautiful neighborhood in those days with lots of teachers and doctors living in our block.

“I was eight years old. Daddy was a telegrapher for Western Union. His office was in the Equitable building, but that was one of the first buildings to go and later they set up a transmission office in the addict of Welch’s restaurant.

“There were any telephones and radios, so we didn’t know about the fire – until the claiming of the fire engines. With so many of them passing, we all ran outside and when we could see the sky to the east all lit up with flames, and the dark black smoke gathering and blowing in the distance”

that, for the little girl, was the beginning of three of the longest event-packed days of a long active life – days of anxiety, of furious chasing around town, of our order world turned suddenly to chaos, of vents that it’s themselves permanently into her mind.

She never forgot them; she could never imagine how any Baltimorean – whether he lived through the fire or not – could ever forget them.

“Later, when I was grown, I work with children in the playground athletic league, and I would ask them what they knew about the Baltimore fire. “It burned me up. They didn’t know a thing. I told him about it and they were shocked. I said to myself. Someday I was going to have to write that story.” One reason the children hadn’t heard was because of the immediate, far-flung, effective action in the city to rebuild.

There was a brief mood of pessimism; but then-Mayor Clay Timanus created a “district commission,” and public officials, merchants, and financiers got to gather with plans and activities.

By the time Rosa Kohler’s playground children came along, but memories of the fire were lost in the first pink glow of Baltimore’s first Renaissance.

But she didn’t intend that it should be lost. “Later, I lived in New York, and we would have a dinner party and I would tell people I was from Baltimore and I would bring up the subject to the fire. “They look at me with eyes full of doubt and it asks, “oh did Baltimore once have a fire?”

“I had always love to Baltimore, but remarks like that – they started my inner fires raging and I began to think again about writing my book.”

Her head was still full of memories, but the first night when her mother disappeared.

“Nobody knew where she was, nobody could call or wire, we were getting information but only through the grapevine.

“Everyone was frantic, we imagine the worst, nobody slept.

“The fire was spreading the other way, but embers were blowing back in our direction, and we never knew whether our house might catch fire.

“Men wore celluloid collars in those days. And I remember one man – and Amber landed on his collar and set fire to him. They had to douse him with a bucket of water to put them out.

“That night, and every block, they set up bucket brigades on the rooftops keeping watch in case the houses of catch fire.

“Next morning mother showed up. She has spent the night with a friend on Biddle Street, helping her pack and move in case the win to turn and flames eat up that part of the city.”

She Still Recalled What the Fire Did to Her Grandfather

“He was in the shoe business. He had a factory on Water Street and three retail shoe stores. One was in the old son building on troll Street in Baltimore Street. I remember it so well, on the same floor was a shop selling Minsk badges and another for the Warner Hat Company. I used asked myself, how does the company make out selling nothing but badges?

“Daddy couldn’t go to work Monday, so he went with my grandfather to see if they could save the factory. There were hordes of people downtown. They came to go to work, just as they always did. They had heard there was a fire, but it was a workday, so they knew they had to get up and go to work.

“The military was out – and dandy fifth – keeping the spectators away from the danger zones. People standing around watching got so excited that sometimes when a wind came up, it would scatter some paper money that somehow didn’t get burnt up. But nobody would bother chasing it.

“They couldn’t save grandfather’s factory. It was completely gone. Everything stank up and burned. They found the foot of water on the floor, and they were sloshing around. Trying to find what might be left when my mother showed up.

“Nobody was supposed to get through the military lines. But mother was good-looking and somehow she made it.

“When she appeared, she looked at my father’s what feet and smiled. She said she knew it would be that way and she had bought him a pair of dry socks.

“Grandfather never rebuilt his factory; he was too old. He did reopen some stores, but he could never get used to selling shoes made by someone else. It was never the same.”

It was in her late teens that rose: the first decided she had to write a book about the fire. She had attended St. Catherine’s normal Institute, at Harlem and Arlington avenues. But she never went to college. Instead, she went to work as a recreation leader, where one of the jobs was telling stories to children.

Naturally, she would tell him about the fire. Later she wanted to be an actress, and read please with the vagabonds and with the war camp community service, the World War I organization providing recreation for servicemen.

She left Baltimore to travel with Chautauqua lectures, drama and other assorted kinds of culture to cities and small towns all over the country.

She became a professional storyteller, and one of the highlights of her career was telling stories at Hull house in Chicago where Jane Adams was at the crest of her fame.

In Chautauqua, she met her husband, Clark Eichelberger, a lecture on international affairs. He subsequently became a United Nations diplomat and has written a number of books in that area.

In the 1950s, [she was then approaching the age of 60] Mrs. Eichelberger took a course at the New York University in writing for children and shortly afterward published her first book, the Bronco close,

On the strength of that success, she has come New York publisher if he wouldn’t be interested in a long dash projected book about the Baltimore fire. He wasn’t.

“He said to me, “but you know, Mrs. Eichelberger, every little town in America has had its big fire.”

“That made me so mad.”

So she decided to write the book 1st and see if she could pedal it afterward

“I wanted children to see the fire as it actually happened. So I centered around the 12-year-old boy named Todd who wanted to become a Western Union telegrapher – he learned the moss code by practicing it on his gate latch – and he carried information to everyone about the fire.

“I get up every morning at 5 o’clock and work on this thing. Later in the day, I had my regular job and my housework to do

“getting up that early, I’ve wondered often how many millions of talented women writers have been smothered under housework. “I finished that manuscript, then I rewrote it, and then I rewrote again, again and again.

“Then I began talking to publishers, but nobody in New York was interested.

“It never occurred to me that there might be a publisher in Baltimore until one day I attended a reunion of old new dealers in Washington, and a friend of mine from Baltimore was there, and she told me about Barber hold bridge and stammer house. “I wrote to Barbara and she was interested right away.

“And that’s how it happened”

“After those kids, I personally told the story of the Baltimore fire to. I’m glad now that finally, it’ll be available to them all.

“My next book? I’m thinking about tackling my memoirs.”

Esther Wilner Hillman

Esther Wilner Hillman

There’s a Messiah on the door jam, and on the window, little decals about Israel. The walls are hung with pictures of children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

And there’s a big homemade greeting card tacked on the kitchen door from someone who I would say loves her.

Esther Wilner Hillman, 82 years old but looking nowhere near that age, is animatedly talking on the telephone, and the soap operas playing on the TV behind her.

But when you tell her you’ve come to hear her reminiscence about the Baltimore fire, everything stops.

Hastily she tells her friend, “I’ll call you back,” hangs up and leaves the instrument off the hook. She quickly turns off the TV. She explains that people are often here because she collects clothing to forward to poor people in Israel. And that today is her 82nd birthday, so she’s getting lots of calls.

But right now, first things first, “I’ve been waiting over 50 years to tell the story about what our Jewish people did in the Baltimore fire. Now that I’ve got a chance to do it, everything else is going to wait, even my birthday calls.”

First, though, a cup of tea – tea with maleness – that’s jelly or preservatives to sweeten it. And the cookie – you can’t drink tea without a cookie. Is it hot enough? If it isn’t hot enough, so warm it up.

Now that she's sure you’re comfortable, she begins her tail.

“I’ve tried to tell the story before, but they weren’t interested. All my life nearly every Friday I’ve been reading writing about the fire, but nobody has ever written what our Jewish people did. It was this way.” And she begins.

“It was bitter cold, just like today. We were living on sharp Street, at Camden.”

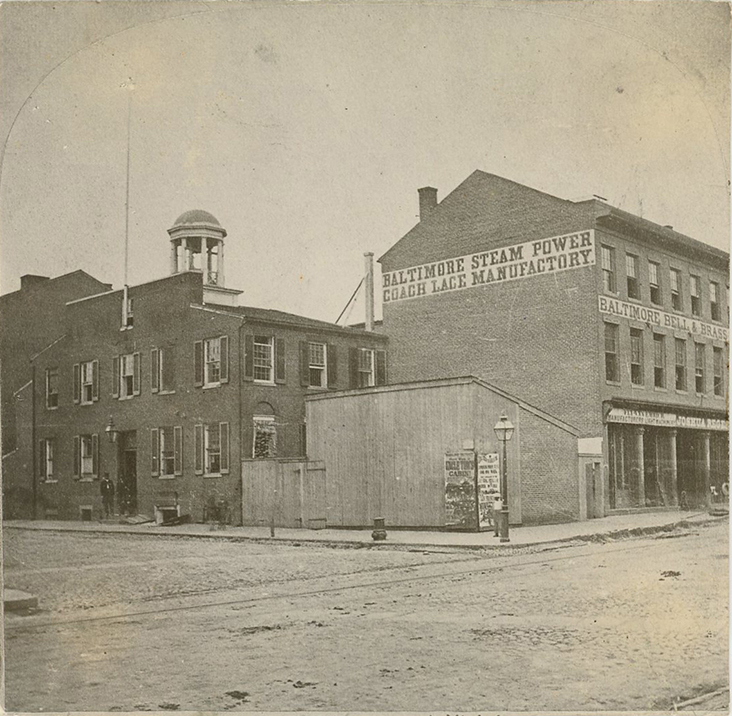

Sharp Street, she explains is the old name for Hopkins place. [It still Calls Sharp St., South of Pratt Street]

“That’s where the fire began, and Johnny Hearst place, right near the corner of German [Now Redwood] and Sharp.

She narrows her eyes and looks off into the distance, the better to see the exact corner.

“He was in the Drygoods and Notions business. So the stuff all over the South,” she looks solicitously into the teacup to be sure it isn’t yet empty, then continues her story.

“In those days, South Baltimore was a Jewish ghetto from Baltimore Street down to about Cross Street market.

“On the Shabbas, everything shut down because everybody went to see.

“But Sundays, they worked. Half a day, from 8 o’clock till two. Other days, they worked 12 hours. And they had to put in six days. Otherwise, they didn’t get their full pay. It was four dollars a week. Imagine, and today they made gets four dollars an hour.

“Anyway, my father worked for soul Ginsberg, whose factor was across the street from the Hertz.

“He’s going to work that morning as usual, at about 10 o’clock he came hurrying home caring these enormous books, weighed down with them. I’d never seen him look so intense and burdened. They were the ledgers from Ginsberg. “He slapped them on the chair and said to my mother, don’t let the children bother them. Tseppenin, that’s the word he used. “Then he ran back for more ledgers, and then he took my older brother, Sam, with him, back to the plant, to help them carry out bolts of cloth. Sam was nine years old. I’ve only seven. The bolts were so heavy, it took three of them to carry each one. But they kept running back and forth bringing more bolts until the police wouldn’t let them go back anymore.

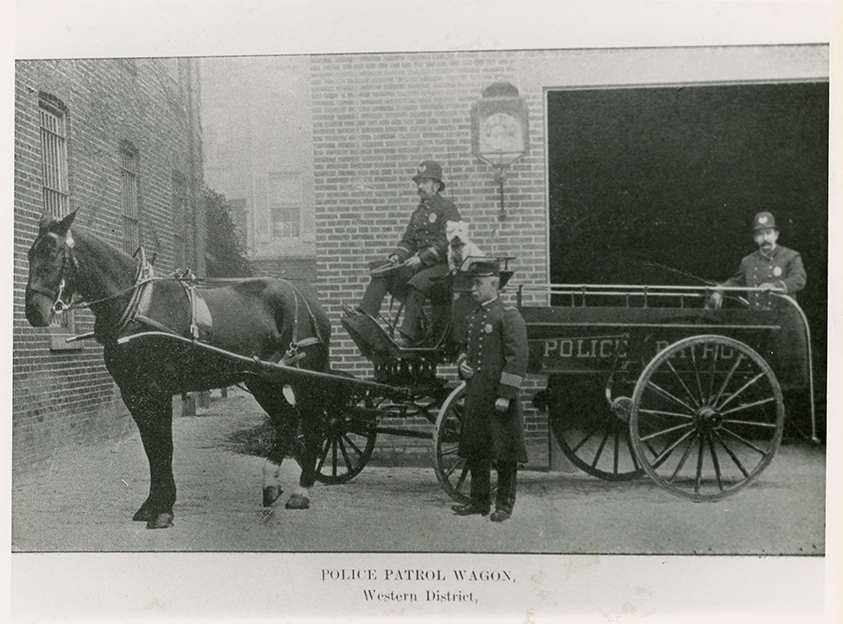

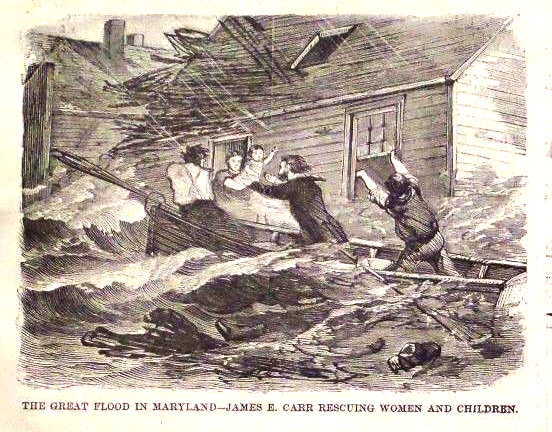

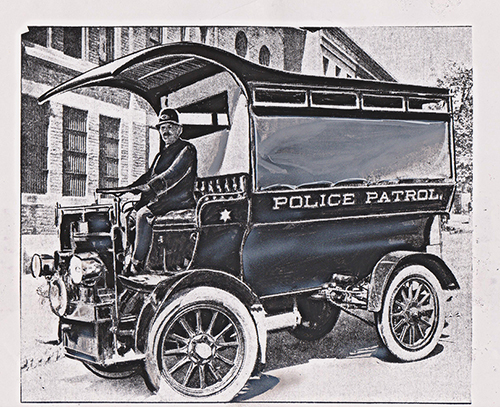

“And then my father told everybody what happened. He had smelled fire and smoke, and a sent some of the workers to break the fire alarm. And then to stand at the corner ~fireman game. Remember, they were horse-drawn engines in those days.

“They saved all they could. What made it so sad was that there was a hardware store next door to the hearse, and they kept barrels of gasoline and coal oil out on the sidewalk – they weren’t allowed to keep them indoors.

“And then the fire read to them they exploded. It was terrible, after that, nobody was allowed to go back in, and the police went house to house throughout the road, telling us to get ready to move out, in case the winds shift toward the south. “We ran upstairs and carried down all our perenes (eiderdown quilts). What else do people have in those days? And then boys ran around and notified everybody who had a wagon to stay on alert – case we had to move. But thank God, the wind didn’t shift to the south.

“That night we children all slept downstairs on the perenes while our parents poured buckets of water on the roof, in case a spark should handle them.

“I remember father on the roof. And a mother on the sidewalk down below, filling the bucket and tying a rope to it so the men could port up.”

She interrupts to refill the plate holding the cookies. Do not homemade she apologizes. But you can’t get around as well as he used to.

“Now where was I? Oh, yes, sleeping on the perenes downstairs. You know, I’ll never forget that. Asked me what happened yesterday, and I won’t be able to tell you. But those days the fire, I’ll never forget.

“You know, it after just a couple of hours it was clear that it was so big that our firemen couldn’t handle it alone. So they sent help from other cities – from Washington, from Philadelphia, from door fall, from Richmond. “Of course, the firemen from out of town couldn’t go home, even the Baltimore firemen couldn’t go home. They would work for four hours, and then they were exhausted needed the rest, but in four hours they had to start again. “So the police came to our neighborhood and asked us to help. “The firemen needed hot coffee, could we keep a pot always going on the stove? And could do firemen come in and sleep in our houses? “Ordinarily we never use the parlor in winter, so it was always cold. We ate all meals in the kitchen. “But my father filled the big Latrobe stove with wood and coal, and we dragged the perenes in there on the floor, and that’s where the firemen slept. “Of course you couldn’t just give a man coffee without a bun. So my mother, like all the other women, began baking bread to feed the firemen. “I remember an old man, his name was Singer, he was very pious, and he kept a strict kosher grocery store. He sent over so many things. Without the charge, naturally. “On Camden Street, a family named Surasky kept the department store. It wasn’t like a department store today, but in those days it seemed very large to us. They sold everything. They sent boots for the firemen, and woolen socks, woolen caps, earmuffs, mittens. Whatever they had they sent, and everything was free of charge.

“My mother worked day and night, the only rest she got was on the couch in the kitchen. And my father and Sam were busy keeping the stove going day and night. “For us children, it was terribly exciting. Although strange men sleeping and eating in our house. “Since they slept around the clock, the house had to stay quiet, and my job was to watch the smaller children so they shouldn’t make any noise.

“Of course, the firemen were all black from the start, and they would wash and dry themselves on our towels – and the towels turned all black. I remember my mother standing all day over the washboard, scrubbing them clean. My father strong lines around the kitchen which were full of drying towels.

Our toilet in those days was outdoors, and we didn’t want to ask tired firemen to use that, so my father provided them buckets. I remember him and my mother caring the full buckets out and empty ones back in.

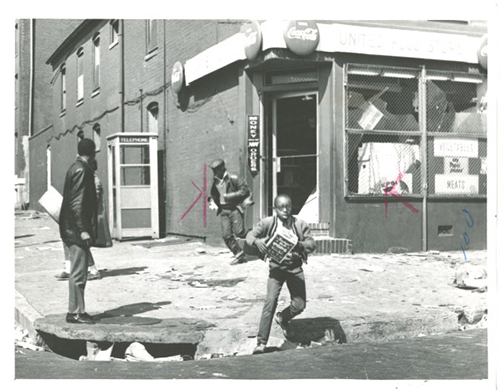

“Only the following Sunday, after it was all over, my father took us up there. What used to be such nice buildings were now all open fields. You couldn’t even tell where the streets had been.

“Everything was smoldering. I remember picking up a piece of black sender. As I held it, it still smoked.

“Back in the house, now the firemen were gone. Everything was so quiet. I remember how I missed the excitement. “But now we had to clean up. “We had no linoleums were rugs on our floors – everything was bare wood. And all the boards were black from soot. “The floors now had to be scrubbed clean. What a job that was!

“Downtown eventually was rebuilt, and the story the fire has been written and told hundreds of times.

“But nobody ever told the part our South Baltimore Jewish community played in it.

“I’ve always said that before I died, I want to tell the world that story.

“Now, thank God I’ve told it so the people will know.”

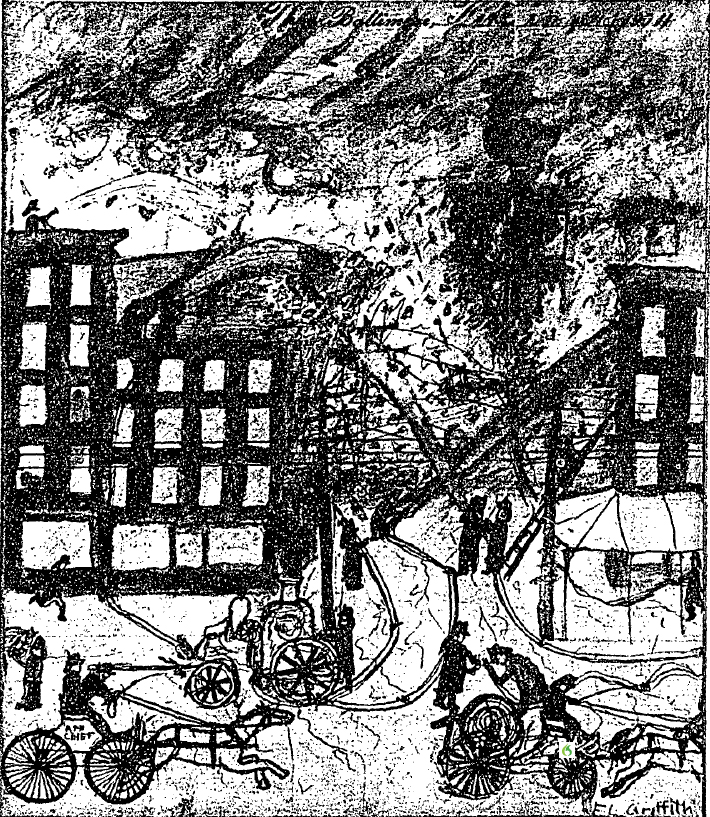

By Forrest Griffith Sr circa 1904

By Forrest Griffith Sr circa 1904

I Remember ... THE BALTIMORE FIRE OF 1904

FORREST GRIFFITH Sr

The Sun (1837-1987); Feb 4, 1973;

pg. SM2

I Remember ... THE BALTIMORE FIRE OF 1904

84-year-old Forrest Griffith recalls the most famous fire in Baltimore city history happening 69 years prior when he was just 15 years old he tells the story as follows

I remember the Baltimore fire of 1904… Sundays were quiet family affairs on N. Carey St. when I was a boy of 15 some families devoted to mornings to church, some to browsing through the Sunday paper, there was the usual huge dinner, which was even at midday. See the rest of the afternoon, the adults had time for a nap and the children did their homework.

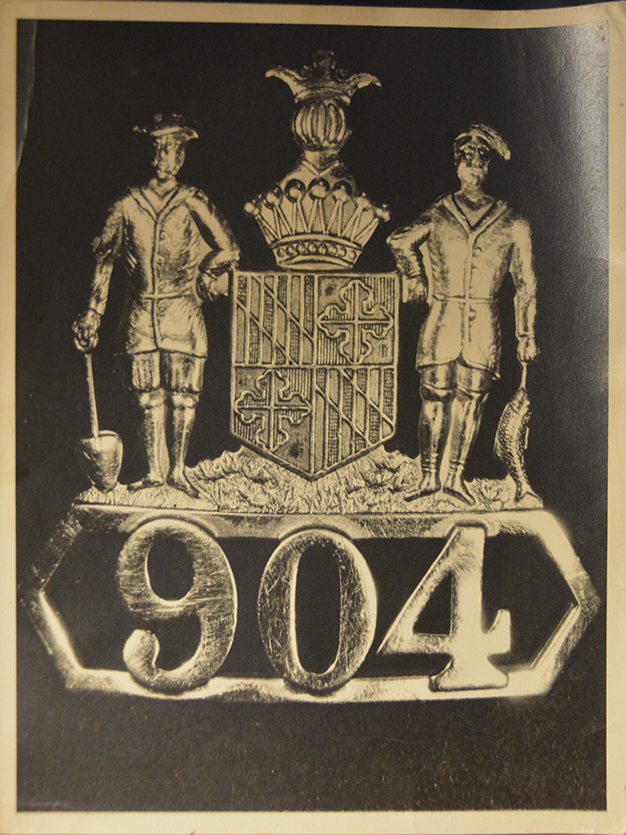

A certain Sunday 69 years ago began as calmly as ever at our house 904 N. Carey, but before noon Joseph began coming in from Sunday school, told by their teachers to go directly home and stay off the streets. There was a big fire downtown.

By noon most of Baltimore new the story. For this particular Sunday was February 7, 1904, and “the big fire downtown” was what is still known in Baltimore as the fire, the biggest in local history.

The fire raged control for two days and flared up again and again in scattered spots for several more. At the end, 140 acres of downtown Baltimore has been reduced to smoldering ashes, 1500 buildings were destroyed. And the loss was estimated at hundred and $50 million.

All boys and men ran to the fire in those days, the men to help, the boys to watch. There was a sort of detached fascination in watching firemen fighting a fire in somebody else’s neighborhood. But watching the fire your own neighborhood, seeing something close and familiar burned, gave you an added tingle of apprehension. So it was with the fire on this day. We live 10 or 12 blocks – a mile or more – from this fire. It was somebody else’s neighborhood, in the matter of distance. But from our street, we could see the clouds of black smoke, shot through the sky of flying sparks. We could smell the smoke, and we could hear the distant clanging of the horse strong fire engines.

My father and I wanted to go right away. My mother didn’t want us to, afraid we might be in danger. There was a sort of compromise. Dinner was almost ready. In those days, meals weren’t prepared by defrosting heating and serving. It took an efficient housewife all of a busy morning to put a good meal together. And when she called the family in the dinner, it was unthinkable that anybody would let it sit there and get cold, earthquake, flood or fire notwithstanding. So after we had our dinner – my father and I went to the fire.

We walked, and our steps quickened with every block. The closer we got the louder the noise. There were the noises of shouting men, the clattering of steel horseshoes on the cobblestones, the rattling fire engines, the shouts of the firemen. And over it all, the frightening roar of the fire itself, a wild and angry, unleashed an invincible sound that I haven’t forgotten. We got so close that the smoke paid us a cough and we had to beat out the flying sparks falling on our clothing.

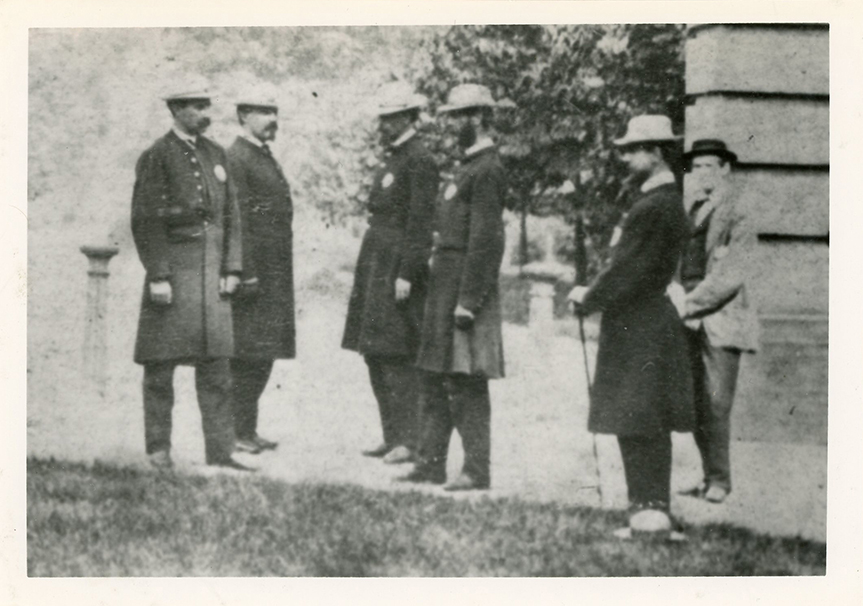

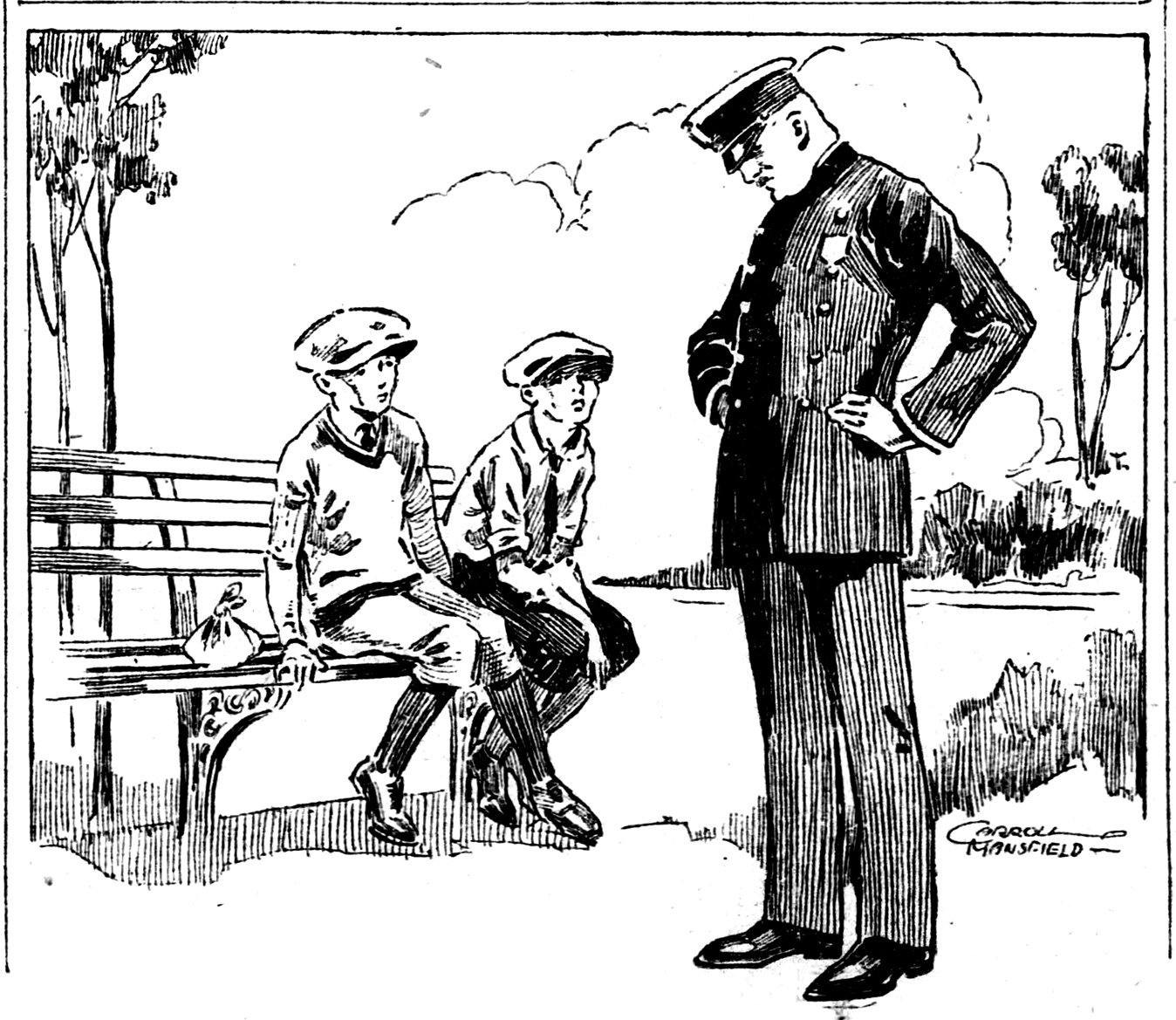

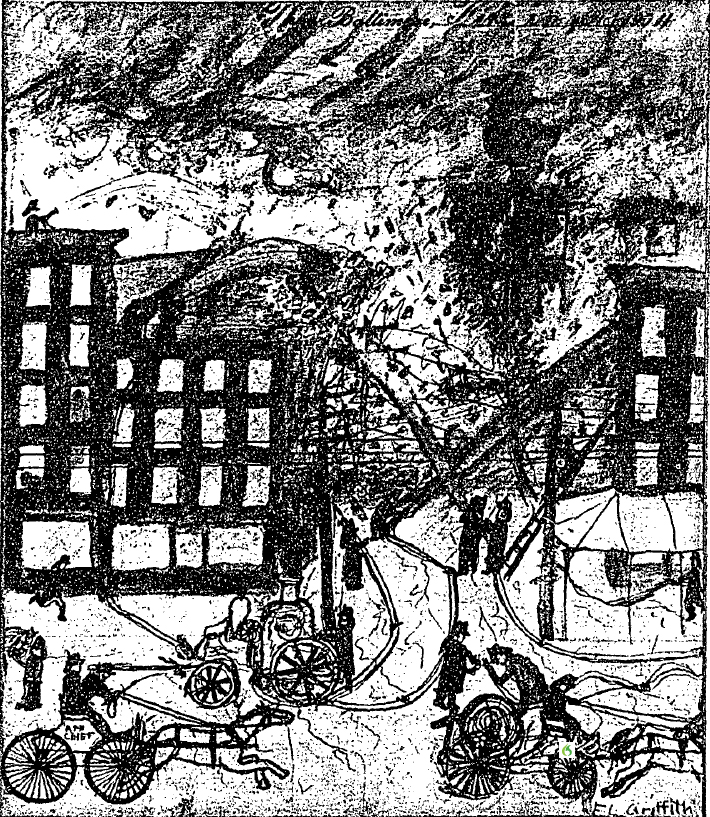

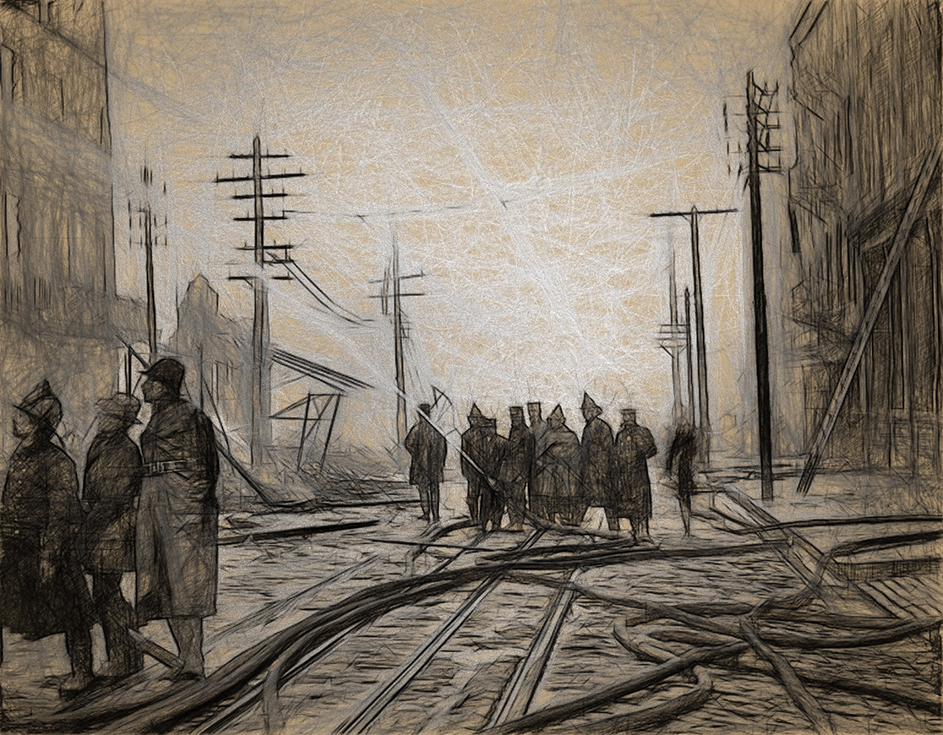

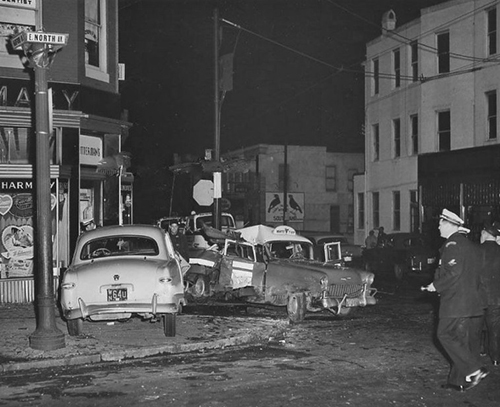

The picture reproduced here is one I drew late that afternoon when we got home. It was my first glimpse of the fire. The scene is the intersection of Mulberry and St. Paul Street. Looking West on Mulberry.

My father was a salesman for the Heinz Company. When we got home, I turned over one of his business letters and sketched the picture with a pencil. I can explain my compulsion to draw the scene, except the new I had seen something terribly important. Later I outlined the pencil line with a pen. I finished the drawing with watercolors.

After the picture was done I lost interest in it. There was too much going on. While the fire burned, and for many days afterward, nobody could think of anything else. At that time I was a student at the high school at Howard and center streets. It later became City College. Classes at our school, and I presume and many other schools, were dismissed for 10 days or two weeks.

I assumed my picture had been thrown away. Then a few years later, my sister India, founded in a drawer somewhere “I like this picture,” she said, “I think it should be preserved” she took it out had it framed and later gave it to me as a birthday present.

I’m glad she did, now I wouldn’t part with it for anything.

In later years I learned to draw much better. I went to the Maryland Institute when it was located at the marketplace – and was graduated in 1912 as a gold-medal student in mechanical arts, which is to say I held my classes’ highest average for my four years there.

But my crew version of the great fire still brings back the feeling I had that day when I got my first look at it.

The picture is now a pattern of smudged browns, Blacks and grays, for the bright colors I applied on that Sunday in 1904 have long since faded to everyone except me.

A writer, who witnessed the Baltimore fire, made this sketched the day the fire began. It depicts what he saw at the intersection of St. Paul and Mulberry streets, looking West on Mulberry Street.

MILLIONS IN A FEW BLOCKS

The Sun (1837-1987); Feb 8, 1904;

pg. 1

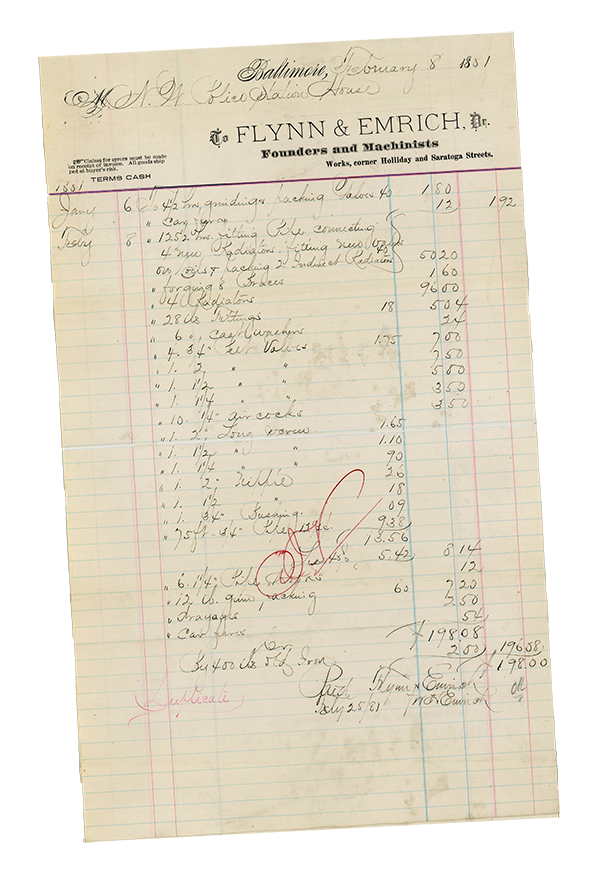

Millions in a Few Blocks a Detailed Estimate of Loss in the Wholesale District

A careful and conservative estimate of the loss in the wholesale business district. In which the fire originated, places it at something over $11 million. This district is bounded by Baltimore, liberty, trolls and Lombard Street and contained many of the largest dry goods, clothing and shoe houses in the city, besides two prominent banks the national exchange and Hopkins place savings bank. This estimate was made for the sun last night by Mr. George E. Taylor, of the insurance firm of Jennise and Taylor, holiday water Street. Mr. Taylor set in his office dictating to a reporter of the sun until it was stated that the fire was only a few doors away when he found it necessary to remove the valuables and papers from his office.

The estimate is for each building in the section, the loss giving representing the building with its contents. According to this the heaviest losers were John E. Hearst and company, R. M. Sutton and company, and the Daniel Miller company all of which were heavily stocked with dry goods, and in each of which cases the loss in building and content was placed at 1 ½ million dollars. The Armstrong, Cator and company’s loss is estimated at half 1 million, and the great majority were hundred thousand dollars or more a piece. This district contained about 125 buildings, among them some of the finest business structures in town, which were occupied by more than 150 firms.

At 330 this Morning

At 330 o’clock this morning the fire had not crossed Jones falls on the East although a number of lumber yards on the west side of the falls were ablaze. The wind was still from the north.

West of trolls and north of Lombard the fire had practically burned out. East of trolls and south of Lombard the flames are still spreading. It was expected to reach Pratt Street before daylight. The fire probably will reach the waterfront west of Jones falls. The Lutheran Church and Broadway and Canton Avenue caught fire at 3 o’clock.

Signs of Abating

Mayor McLane and Dr. Geer have just returned from a circuit of the fire, the mayor said; “I feel the conflagration shows some signs of abating. I have received a telegram from New York stating that the fire department of that city has sent over six engines, six those carriages, six trucks and horses. These will probably reach Baltimore between six and 7:00 AM” police Marshall Farnan said: “I think the fire is practically under control.”

FLAMES SWEEP SOUTHWARD

The Sun (1837-1987); Feb 8, 1904;

pg. 2

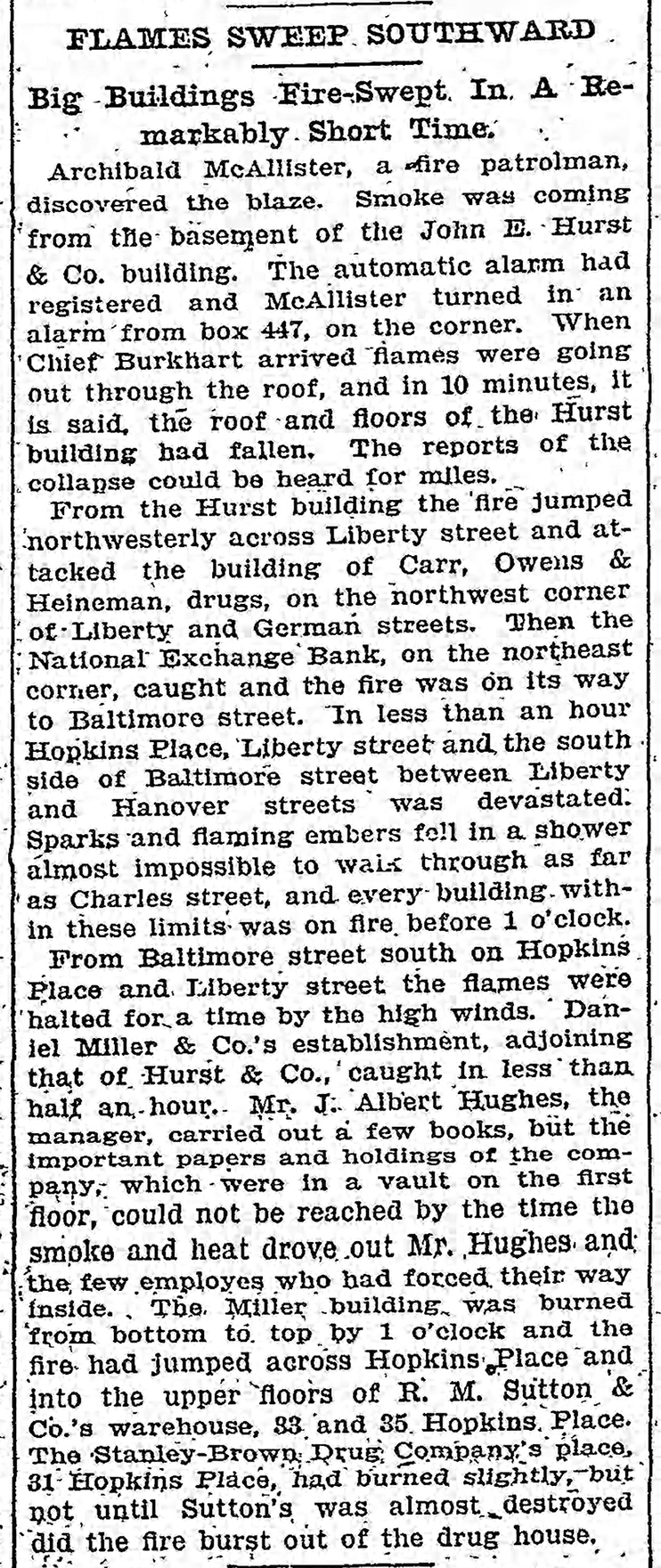

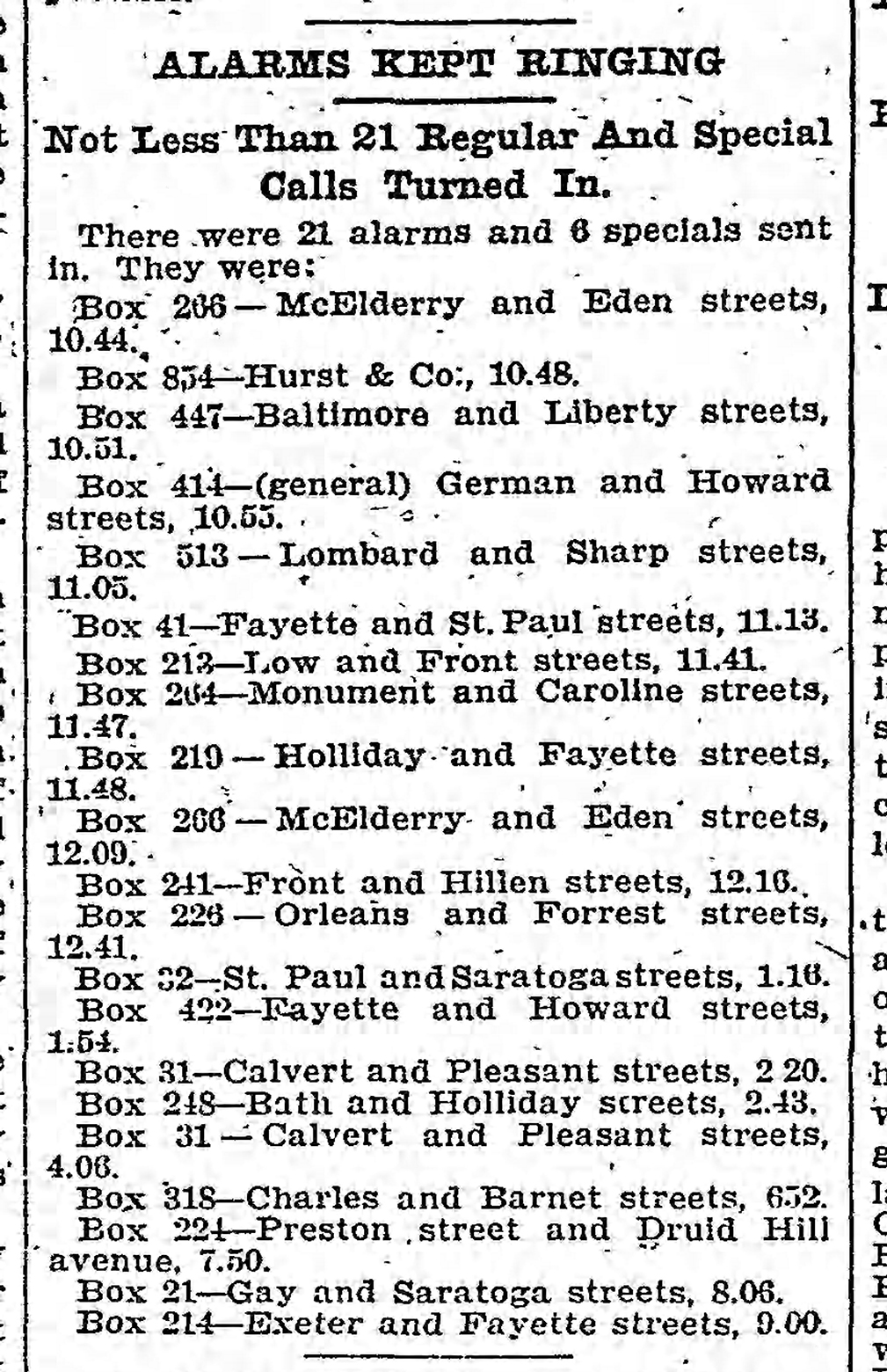

Big buildings fire swept in a remarkably short time

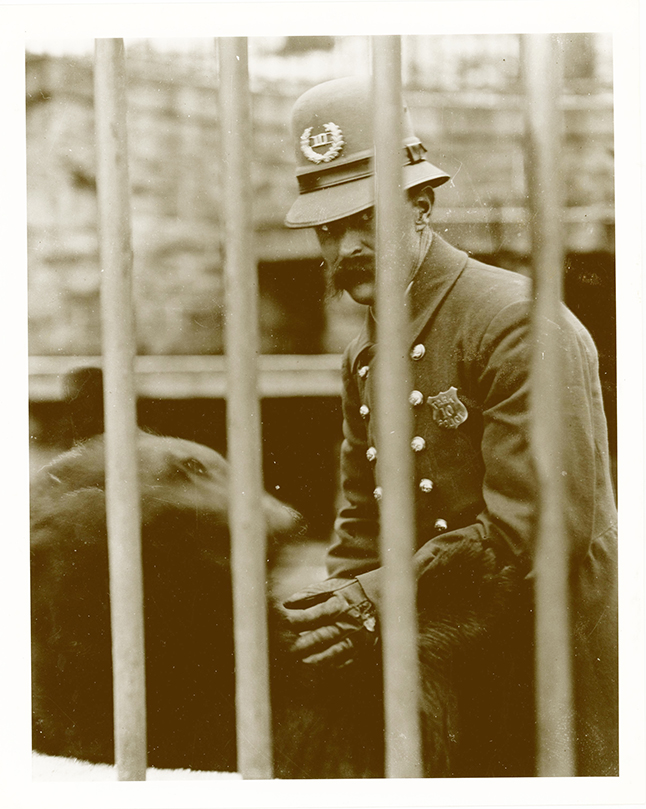

Archibald McAllister, a fire patrolman, discovered the blaze. Smoke was coming from the basement of the John E Hurst and company building. The automatic alarm has registered and McAllister turned in the alarm from box 447, on the corner. When chief Burkart arrived flames were going out through the roof, and in 10 minutes, it is said, and the roof and the floors of the Hurst building had fallen. The reports of the collapse could be heard for miles.

For the Hurst building, the fire jumped northwesterly across liberty Street and attacked the building of Carr, Owens and Hindman, drugs, on the northwest corner of liberty and German streets. Then the national exchange bank, on the northeast corner, court and the fire was on its way to Baltimore Street. In less than an hour Hopkins place, liberty Street and the south side of Baltimore Street between liberty and Hanover Street was devastated.

Sparks inflaming Amberg fell in a shower almost impossible to walk through as far as Charles Street, and every building within these limits was on fire before 1 o’clock.

From Baltimore Street south on Hopkins place in liberty Street the flames were halted for a time by the high winds. Daniel Miller and company’s establishment, adjoining that of Hurst and company, caught in less than a half an hour. Mr. J. Albert Hughes, the manager, carried out a few books, but the important papers and holdings of the company, which were in a vault on the first floor, could not be reached by the time the smoke and heat drove out Mr. Hughes and a few employees who had forced their way inside. The Miller building was burned from bottom to top by 1 o’clock and the fire had jumped across Hopkins place and into the upper floors of R. M. Sutton and company warehouse, 33 and 35 Hopkins Pl. The Stanley Brown drug companies place, 31 Hopkins Pl., had burned slightly, but not until Suttons was almost destroyed in the fire burst out of the drug house.

TWENTY-FOUR BLOCKS BURNED IN HEART OF BALTIMORE

The Sun (1837-1987); Feb 8, 1904;

pg. 1

City’s most valuable buildings in ruins – loss Variously estimated at from $50 million-$80 million

Blaze Still Sprinting Eastward and Southward At 3:30 AM

Starting in John E. Hurst building the fires sweep South to Lombard, East of Holliday and North to Lexington, destroying wholesale business houses, banks, Continental, equitable, Calvert, B. And oh. Central, the sun, and other large buildings

Fire, which started at 1050 o’clock yesterday morning, devastated practically the entire central business district of Baltimore and at midnight the flames were still raging with his much fury as at the beginning. To all appearances, Baltimore’s business section is doomed. Many of the principal banking institutions, all the leading trust companies, all the largest wholesale houses, all the newspaper offices, many of the principal retail stores and thousands of small establishes went up in flames, and in most cases, the contents were completely destroyed.

What the loss will be in dollars no man can even estimate, but the sum will be so gigantic that it is hard for the average minded to grasp its magnitude. In addition to the pecuniary loss, will be the immense amount of business lost by the necessary interruption to business while the many firms whose places are destroyed or making arrangements for resuming business.

There is little doubt that many men, formerly prosperous, will be ruined by the events of the last 24 hours. Many of them carry little or no insurance, and it is doubtful if many of the insurance companies will be able to pay their losses dollar for dollar, and those that do will probably require time in which to arrange for the payment.

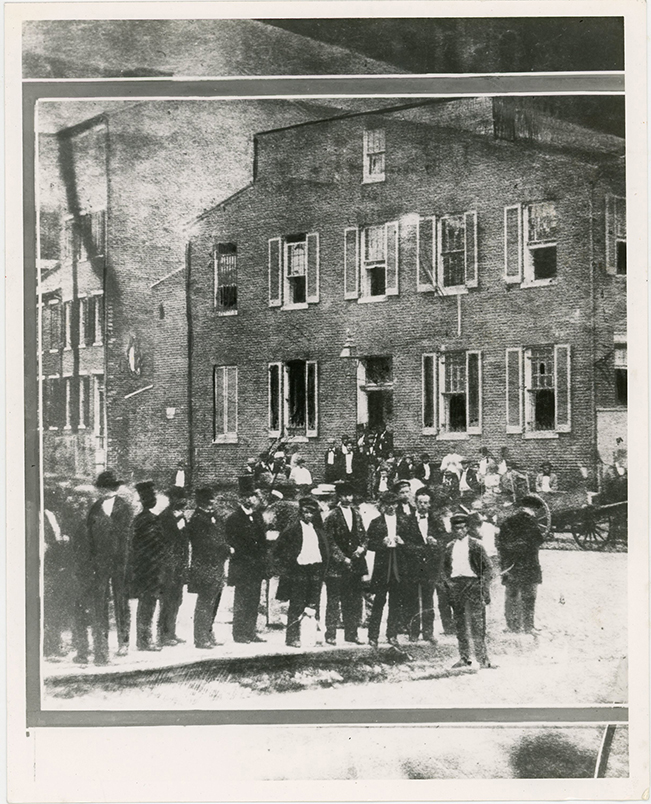

Appalled at the Silence

All day and all night throngs crowd at the streets, blocking every Avenue to the fire district and moving back out of danger only when forced to do so by the police on duty. Many of the spectators Saul they’re all the way up in flames before their eyes, and there were men with hopeless faces and the spring expressions seen on every hand. In fact, the throng seemed stunned with the magnitude of the disaster and scarcely seemed to realize the extent of it all.

They stood around usually in days silence, and only occasionally with the word of despair be heard. That they were almost disheartened was apparent to the casual observer, and there is little wonder, for the crushing stroke fell with the suddenness and lightning from the cloudless sky.

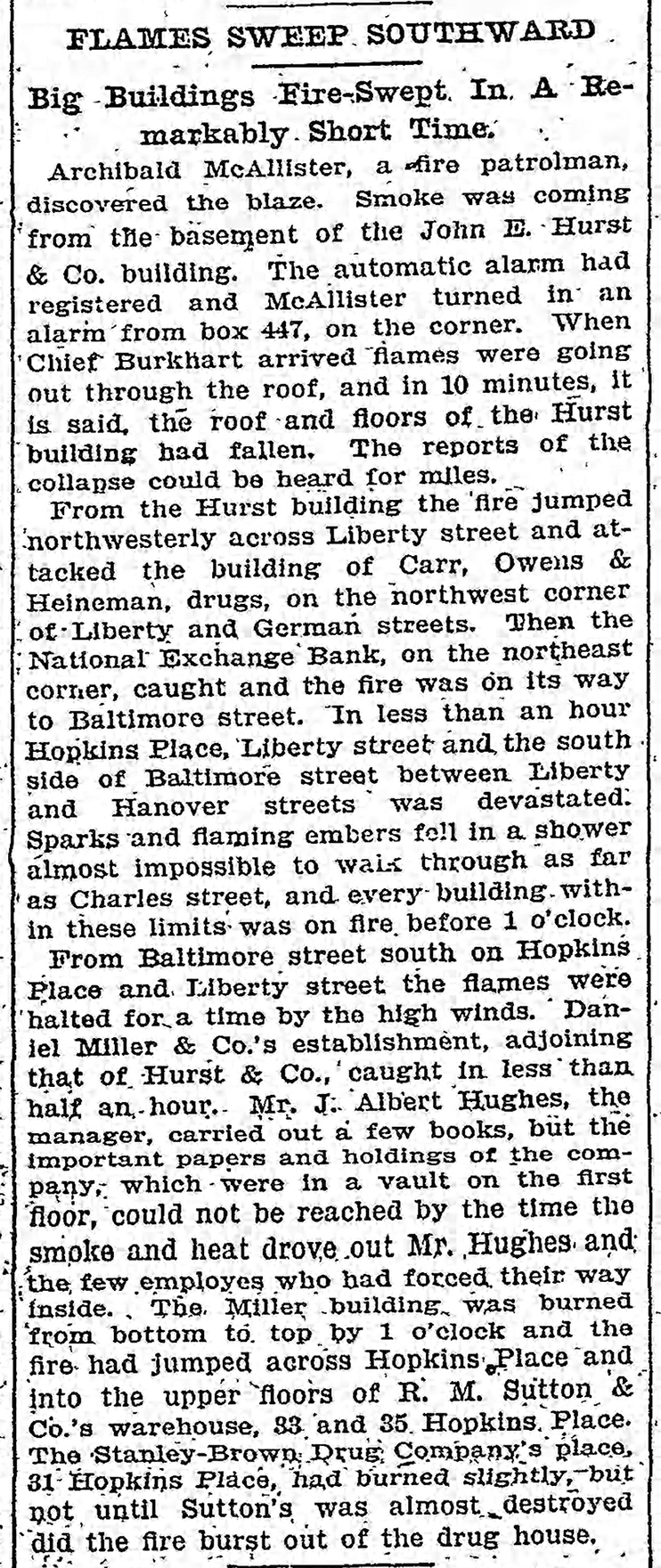

Starts in Hurst Building

At 1050 o’clock in the morning the automatic fire alarm box, number 854, in the basement of the wholesale dry goods house of John E Hurst and company, German Street and Hopkins place, sounded an alarm. Almost before the alarm had reached the various engine houses the entire building was boring mass of flames from top to bottom.

Gasoline Explodes

After burning fiercely for perhaps 10 minutes there was a loud explosion from the interior of the building as the gasoline tank he used for the engine in the building let go. Instantly the immense structure collapsed and the flying, blaming the breeze caused the flames to be communicated to the adjacent buildings on all four corners.

By this time the first of the fire apparatus had reached the scene and was quickly put to work, but the fire had already gone beyond control and swift with irreversible and irresistible force and credulous swiftness on its devastating way. It was known that the configuration would prove vastly destructive, but not one of those who witnessed it at this time of imagined for an instant the terrible results of this would ensue.

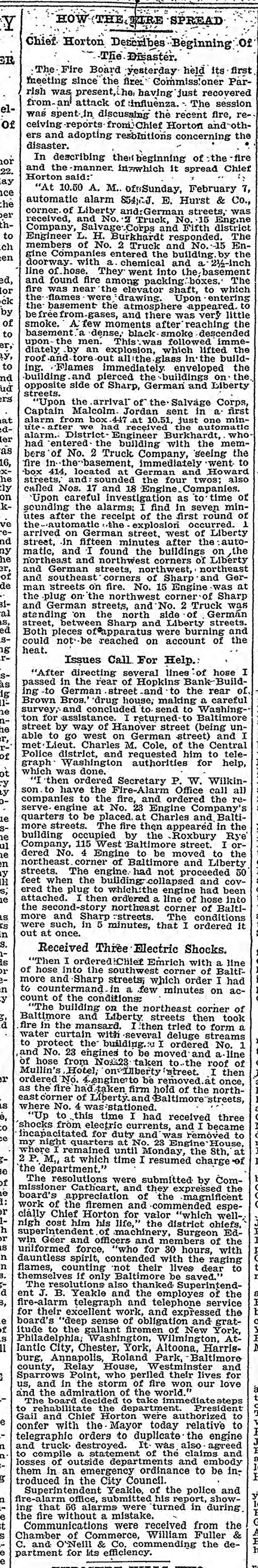

Chief Horton Disabled

Chief engineer Horton, of the fire department, was quickly won the ground, but scarcely had he begun to direct the force of firemen when a live trolley wire fell on him at the corner of liberty and Baltimore streets, knocking him senseless, and he had to be carried to his home and placed in bed. By this accident, the city was deprived of the services of its most experienced and trusted firefighter, and although district chief Emerich, who succeeded chief Horton in command on the ground, did apparently all that was possible, those present could not but regret that chief Horton was not there.

Mayor McLane came down and was on the ground until a late hour in the night. He walked around the burning district and conferred with various officials as to the steps necessary to be taken and various stages of the fire.

It is thought the loss will be over $50 million.

Aid from Washington

For general alarms, force is the least sent in and within half an hour after the first alarm, every piece of fire apparatus in Baltimore was on the ground and at work. Realizing the gravity of the peril a telegram was sent to Washington for aid and two engines from that city were placed on a special train and hurried to the city over the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in record-breaking time. It was said that the trip was made in 37 minutes.

It was an all aspiring site to witness the progress of the flames. A building eight or 10 stories in height would suddenly break in the flames from top to bottom almost in an instant and wood burning fiercely until with a crash that would be heard for blocks the walls would collapse and the spot is marked only by a heap blazing ruin. The crash of falling walls is almost incessant and now and then could be heard the muffled form of an explosion as some gasoline tank or chemical substance became ignited by the heat and let go with a terrific force.

Many Firemen Injured

Every minute almost the lives of the firemen were in imminent danger from falling walls or leaping flames, and more than 50 of them were carried from the ground more or less severely burned, and dismayed by the danger or hopelessness of the task, however, they continued the unequal struggle, and took the hose into narrow alleys, where the flames ward menacingly overhead on both sides of them, and directed streams of water where it was thought of some effect could be produced.

Long matters were placed against the walls of fiercely burning buildings and brave firemen climbed up and broken windows and turned streams of water into the doom buildings until the walls weighed and rocked and the crowd of onlookers shouted to them to come down, and many turned away their eyes and momentary appreciation of a fatal calamity.

Apparently, every person in Baltimore was in the vicinity of the fire, and the various streets leading to the fire district will Paxil during the entire day. The entire police force, in charge of marshal Farnan and deputy Marshal Manning, was on the ground and with ropes succeeded in keeping the crowds back from the dangerous points. As the fire spread further and further the ropes were shifted and the crowds moved back one block at a time.

Great Building Gone

Dissection devastated contains the largest and most modern buildings in the city and this renders the calamity the more appalling. Immense office buildings, 10 and 20 stories high, large modern wholesale houses made of brick and steel, all disappeared as it builds of the flimsiest material.

The exact origin of the fire is not known, but the explosion which started spread of the flames to other buildings is said to have been caused by gasoline engine in the Hurst building Mr. S. F. Ball on Fayette Street who was standing on the corner of Sharp in Baltimore Street when the fire first broke out, said that in less than 10 minutes the entire Hurst building was a boring mass of flames from top to bottom. When the explosion occurred Mr. Ball was cut on both hands and a whole was cut through his hat by flying fragments of glass.

To Lombard St.

From German Street fire spread rapidly to Lombard Street, leaping from building to building, and sometimes skipping two or three buildings at a time and in this way a block would become ignited in a remarkably short space of time. At Lombard Street the fire paused for some time and the large building of Guggenheimer, will, and company stood for a time apparently undamaged. It was eventually doomed, however, and all arrangements were made for Dynamiting it in order to save the Lloyd L. Jackson building, just across Lombard Street. The Guggenheimer, well and company building suddenly burst into flame and in a very short time the floors began falling in with a crash, the heaviness of graphing machinery, when many times, causing a detonation that made many think the place was really being dynamited. The walls quickly followed the floors and the Jackson building was saved after a hard struggle.

A number of other buildings on the south side of Lombard Street became ignited, however, and both sides of that Street from liberty to Charles or practically ruined, the houses on the north side being completely destroyed and those on the south side, with the exception of the Jackson building, badly damaged

Across Sharp Street

Meantime the flames had swept through the block to the east and quickly began destruction of the buildings on the west side of Sharp Street. With scarcely a pause they jumped over to the east side of Sharp Street and the large roller buildings on that side of the street began to sparkle and burn. Hardly had a portion of the fire apparatus been shifted to meet the new point threatened when the fire was sweeping madly across to the west side of Hanover Street, and there the scene was repeated. Almost before the firemen realize the fact the building on the east side of Hanover Street was blazing.

To Baltimore Street

At this time the scene in this portion of the burning district was magnificent in its spectacular grandeur. Looking up Hanover Street to Baltimore nothing but a seething boring mass of flames, mingled with dense smoke, could be seen. Baltimore Street itself was a boring furnace. On every side were flying senders, the war of the flame was broken at frequent intervals by the crash of falling walls and now and again the detonation of some explosive sound it along with other sounds of destruction.

Dynamite Used

After crossing Hanover Street there was little to oppose the one rushing flames and the blaze continued its destructive course without a check to Charles Street. Prior to this time there have been many talks of dynamiting the material was on the ground and Mr. Roy C. Lafferty, the government expert, who would come from worse and especially to take charge of the work of dynamiting the buildings, was on the ground with his apparatus and readiness. By the time it was thoroughly realized that the flames were completely beyond control and only desperate measures could be expected to relieve the situation. In this straight city engineer Sindall and Mr. Lafferty lady charge in the building adjoining Armstrong, Cator, and companies on the West and set it off. The building fell with a crash but the blazing ruins ignited the Armstrong building and the situation was if anything made worse.

Armstrong, Cator and company’s building burned rapidly. A largely charged dynamite was let off in it, but the structure failed to collapse and the idea of destroying it with dynamite was abandoned.

The flames by this time were raging fiercely all along German Street to Charles Street and it was then that Mr. Lafferty set off six charges of dynamite, each charge containing 100 pounds, in the building at the south-west corner of Charles and German streets the tremendous force of the explosion tore out massive granite columns that supported the building and left it with apparently almost no support, but those walls failed to collapse and stood until the flames had crossed Charles Street and were eating into the block between Charles and light streets.

The Carrollton Goes

The fire had meantime been communicating to a row of buildings on South Charles Street, between German and Lombard streets, and all those places, occupied principally by wholesale produce and grain dealers, were in flames.

Shortly before midnight, the Carrollton hotel was in flames and the wire was sweeping toward Calvert Street with irresistible fury.

The firemen working on the south side has succeeded in checking the flames at Lombard Street, and as the wind was blowing from the Northwest there was no danger of it spreading further in that direction. The Western limit had also been reached and Howard Street and the danger was now on the east and north.

The progress of the flames toward the north had in the meantime been so rapid as to be simply appalling. From structure to structure the blue, looking up the massive buildings as if they were composed of paper. In the block between German and Baltimore Street, they flew along, and almost before it could be realized the building along Baltimore Street were blazing from the roof to the basement.

Mullins in Ruins

For a time it was hoped the fire could be kept from crossing to the north side of Baltimore Street and the firemen made a desperate effort to prevent it. The effort was useless, however, and soon the tall, narrow buildings of Mullin’s hotel began to dart out tongues of flames from several stories and in a few minutes, the entire building was an immense flaming torch. At almost the same instance the remainder of the building between sharp and liberty streets were blazed and the fire began its march to the North. The small two and three-story buildings on little sharp Street burned comparatively slowly in this narrow space and to Washington companies fought a plucky battle with the devouring element.

They were Hammond in on both sides by fire and directed the streams at the buildings from which smoke and flames were pouring, at a distance of only two or 3 yards.

Across Charles Street

it was utterly, heartbreakingly useless. The flames darted rapidly from place to place, and soon the entire south side of Fayette Street was in a grasp of the flames. Down Fayette Street, to Charles Street, they swept, and in a space of time that seemed incredibly short, the building occupied by J. W. Pots and company was evidently doomed.

Seeing that nothing could save it Mr. Fendall, acting under instruction from chief Emerich, decided to destroy the building with dynamite, in the hope of preventing the fire from crossing Charles Street. The explosion was successful in accomplishing the object, and the entire corner collapsed instantly, but this had apparently, no effect upon the progress of the fire, for almost before the sound of the falling walls had died away the building on the east side of Charles Street began to blaze, and it was evident that the block between trolls and St. Paul Street was doomed.

Calvert and Equitable Company

And desperate, but futile, effort to prevent the fire from going any further to the east, building after building was done dynamited in this block, but it was all of no avail and the fire proceeded steadily forward. The daily record building was soon in flames, and not many minutes later the fire had leaped over St. Paul Street and the lofty, massive Calvert building began to admit smoke and flame. The Equitable building, just over a narrow alley, quickly followed, and these two immense buildings gave forth a glare that lighted the city for miles around.

It was thought that the fire could be prevented from crossing to the north side of Fayette Street and here again a desperate stand was made by firemen. Again it was useless, and soon the large building Hall, Haddington, and company, on the northwest corner of Charles and Fayette Street, was blazing brightly. With scarcely a pause the fire darted across to the east side of Charles Street and began to lap up to handsome building of the union trust company, while at the same time the large buildings to the west of Hall, Haddington, and company, occupied by wise brothers and Oppenheim, Oberndorf and company, were in flames throughout.

DEVASTATING FIRE IS STOPPED AT LAST

The Sun (1837-1987); Feb 9, 1904;

pg. 2 Declared under control at 5 PM after raging 30 hours

Leaps the Falls into East Baltimore

The Loss Now Estimated At From $75 Million to $150 Million

On Philpott Street – Business Heart of City a Scene of Desolation

After 30 hours defiance of all human agencies, the fire which began at 11 o’clock Sunday morning was officially declared under control at 5 o’clock tonight. In the burned district extending from liberty on the West, the Philpott Street on the East, and from Pratt Street on the south to Lexington Street on the north small islands of fire continue in a desolate waste but they have all ceased to menace adjoining property.

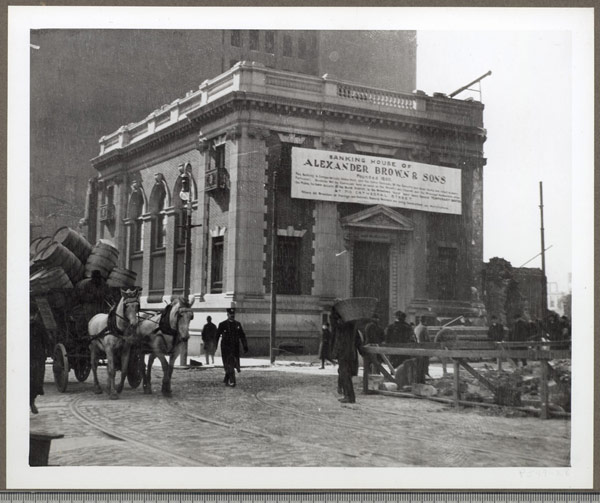

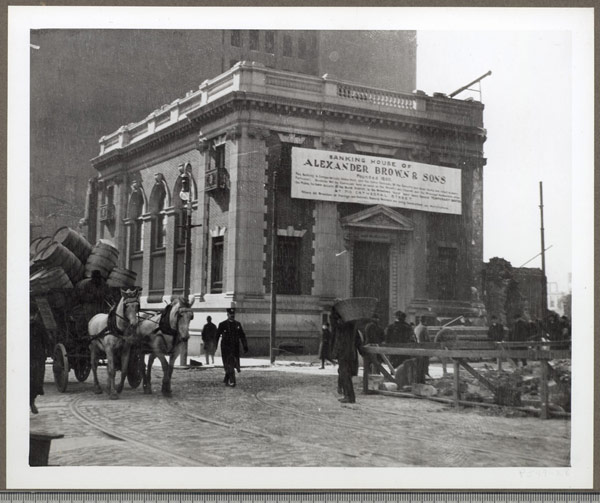

Up to last night, the loss was conservatively estimated by Mr. Alexander Brown and various prominent real estate and insurance men at from $75 million $250 million. These estimates are of course rough and not intended to be accurate for there is as yet no way of arriving at a definite estimate.

It is impossible for the human mind to conceive the magnitude of the disaster and it is utterly beyond the power of man to approximately depict the extent of the ruin and the far-reaching and disastrous consequences of the calamity.

Imagine a beautiful modern city of over 600,000 souls, with all the building, needs to house the population and the thousands of buildings needed to provide for its material prosperity and enterprise. Wholesale houses, built with all the massive stability that modern architectural ingenuity can suggest: elaborate financial establishments constructed with an eye to substantial richness and ornate design, lofty skyscrapers of handsome finish and magnificence of detail wearing far above the earth: elaborate retail stores, fitted in the expensive and artistic manner necessary to attract 20th-century buyers: immense containing all the latest and most expensive, machinery for supplying the critical needs of the present generation in the shortest possible time and in the least expensive manner. All of these and many more buildings, occupying block after block of busy streets and comprising the very center of commercial life, from which the entire population must draw its sustenance, either directly or indirectly.

The men of wealth were dependent solely upon this section for their annual income and the humble toiler was equally dependent upon it for his daily bread. The small merchant and Ardisson looked to the workers of this district for his patrons add prosperity and one and all the city inhabitants must derive their support from the products and profits of this section.

All this essential portion of Baltimore’s property and almost existence, is gone like the mists of morning, wiped out in a day, and in magnificent array of buildings the visible sign of our greatness and place among the cities of the land is tumbled around the ears of the citizens like house of cards knocked over as if in a wanton sport by the titanic hand of the giant fire

Ruin and Devastation

The erstwhile busy streets which echoed to the rumble of traffic are now choked and blocked from curb to curb was half burnt bricks, tangled masses of wires and long electric poles, and the citizens who tread them almost daily for years of the long life fails to recognize them. On each side, where formerly the vision was bounded by solid rows of bricks, the eye passes through the dismantled shells of towering walls or forms unobstructed to more distant scenes of ruin and devastation; where 48 hours ago the trolley cars applied unceasingly and the vehicles in traffic or pleasure wound in and out and the prosperous, happy pedestrians thronged on business or pleasure intent, the monopoly of desolation is relieved only by the sight of two or three workmen making their way slowly and toilsomely over piles of debris in an effort to cut away the tangle wires or by placing dynamite under tottering walls which threaten to topple on the heads of passersby and causing more destruction, clear the way for the Phoenix of the new Baltimore to rise from the ashes of her old self by the indomitable pluck and ingenuity of her people.

The Zone of Ruin

Starting at the corner of Lombard and Liberty streets, the fire zone extends in a rectangular five blocks in up to Calvert Street. At this point the varying winds caused the path of destruction to wind by devious and eccentric ways down to Jones’s falls, taking in the territory as far South as the North side of Pratt Street. At the falls a branch of the flames by some strange fatality of the wind, switch back and traversed the south side of Pratt Street to light Street, destroying every building along both sides of Pratt Street to the waterfront. Thence apparently taking the waterfront as a boundary, the flames swept down toward the east, consuming everything in their track and leaving only heaps of blackened and worthless ruins to Mark their path.

Help from Other Cities

Early Sunday it was realized that the fire department of this city was totally inadequate to cope with the conflagration and request for assistance were sent to Washington, Philadelphia, New York, Wilmington, Annapolis and other nearby towns the response was prompt and generous Washington sent three companies with apparatus, New York sent seven companies, Philadelphia responded with several companies, Wilmington sent one company, Annapolis sent almost her entire force, Chester Pennsylvania sent one company, all the suburban towns around Baltimore sent in their quotas and yesterday afternoon a small army of firemen finally baffled the flames.

Errors of Judgment

Many experienced firefighters expressed the opinion that, in the exigencies of the tremendous battle with the flames Sunday, when the fire first started, serious mistakes and judgment were made by those in charge it is said, that the men of the engine companies were placed in many instances where the danger to their own lives was greatest and the chance of any beneficial result almost nothing. It was remarked that almost the entire by am of water used was directed at buildings that were either burning fiercely or hopelessly doomed. By this method it is said, the firemen were placed in imminent danger of being crushed by falling walls or suffocated by the densely growing smoke. Time and again a lofty wall would totter and tremble for an instant and with an ominous rumble fall on the narrow street, while the members of the fire company who had been placed directly under it would barely escape destruction by a precipitate flight.

Many thought the available streams of water could have been used to much better advantage and the lives of the brave firemen better safeguarded if the streams had been directed principally to the buildings in the pathway of and not immediately contagious to the flames. By thoroughly drenching these buildings in advance of the fire, it is said, there would have been a much better chance for effective results.

Why Dynamite Failed

The same complaint was made of the use to which the hundreds of pounds of dynamite was put. The general opinion was that its use was too long delayed, and when it was decided to use it those in charge placed the charges in buildings too close to the flames and in such small quantities as to be entirely inadequate for the purpose designed.

The case of Armstrong, Cator and company building was cited in proof of this idea. It was pointed out that the dynamite was placed in an adjoining building already ignited and the ensuing explosion merely causes the flames to scatter and the burning debris set fire to the Armstrong building, causing the fire to spread with accelerated rapidity.

It was said that the use of dynamite was advised as early as 3 o’clock Sunday afternoon, and it was then pointed out that nothing else could be expected to bulk the flames, but city officials and those in charge of the fire, it is said, declined to take the responsibility of ordering the use of explosive and precious time was then lost.

When the dynamite was finally used, it is said, the charges should have been placed in buildings at some distance from the fire as entire block should have been demolished, thus providing a wide space over which the flames would have been compelled to leap in order to proceed onward much is allowed for the pressure under which the officials were working and stupendous nature of the unaccustomed responsibility which was thrust upon them but many persons cannot help sighing as they recall the fate of the brave firemen and think that he might have been spared had a different and bolder policy been used in fighting the fire.

Peril from Gasoline

Many expressions oh wonder were also heard at the immensity of the lesson that Baltimore had been taught in regard to the danger of the indiscriminate use and storage of gasoline in the city. For several years the sun has persistently and repeatedly pointed out the dangers of this treacherous and powerful explosive and has published case after case of loss of life or serious injury caused by this means, but the authorities have procrastinated and temper rise until this awful calamity to everyone the wisdom of the warnings of the Sun.